Arnold Joseph Toynbee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Contributor, Greece

in ''The Balkans: A History of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Rumania, Turkey'', various authors (Oxford, Clarendon Press 1915)

''British View of the Ukrainian Question''

(Ukrainian Federation of U.S., New York, 1916) *Editor, '' The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Fallodon by Viscount Bryce, with a Preface by Viscount Bryce'' (Hodder & Stoughton and His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1916) *''The Destruction of Poland: A Study in German Efficiency'' (1916) *''The Belgian Deportations, with a statement by Viscount Bryce'' (T. Fisher Unwin 1917) *''The German Terror in Belgium: An Historical Record'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1917) *''The German Terror in France: An Historical Record'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1917) *''Turkey: A Past and a Future'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1917)

''The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilizations'' (Constable 1922)

*Introduction and translations, ''Greek Civilization and Character: The Self-Revelation of Ancient Greek Society'' (Dent 1924) *Introduction and translations, ''Greek Historical Thought from Homer to the Age of Heraclius, with two pieces newly translated by Gilbert Murray'' (Dent 1924) *Contributor, ''The Non-Arab Territories of the Ottoman Empire since the Armistice of 30 October 1918'', in H. W. V. Temperley (editor), ''A History of the Peace Conference of Paris'', Vol. VI (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the British Institute of International Affairs 1924) *''The World after the Peace Conference, Being an Epilogue to the "History of the Peace Conference of Paris" and a Prologue to the "Survey of International Affairs, 1920–1923"'' (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the British Institute of International Affairs 1925). Published on its own, but Toynbee writes that it was "originally written as an introduction to the Survey of International Affairs in 1920–1923, and was intended for publication as part of the same volume". *With Kenneth P. Kirkwood, ''Turkey'' (Benn 1926, in Modern Nations series edited by H. A. L. Fisher) *''The Conduct of British Empire Foreign Relations since the Peace Settlement'' (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs 1928) *''A Journey to China, or Things Which Are Seen'' (Constable 1931) *Editor, ''British Commonwealth Relations, Proceedings of the First Unofficial Conference at Toronto, 11–21 September 1933'', with a foreword by Robert L. Borden (Oxford University Press under the joint auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs and the Canadian Institute of International Affairs 1934)

''A Study of History''

**Vol I: Introduction; The Geneses of Civilizations **Vol II: The Geneses of Civilizations **Vol III: The Growths of Civilizations ::(Oxford University Press 1934) *Editor, with J. A. K. Thomson, ''Essays in Honour of Gilbert Murray'' (George Allen & Unwin 1936)

''A Study of History''

** Vol IV: The Breakdowns of Civilizations ** Vol V: The Disintegrations of Civilizations **Vol VI: The Disintegrations of Civilizations ::(Oxford University Press 1939) * D. C. Somervell, ''A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-VI'', with a preface by Toynbee (Oxford University Press 1946) *''Civilization on Trial'' (Oxford University Press 1948) *''The Prospects of Western Civilization'' (New York, Columbia University Press 1949). Lectures delivered at Columbia University on themes from a then-unpublished part of ''A Study of History''. Published "by arrangement with Oxford University Press in an edition limited to 400 copies and not to be reissued". * Albert Vann Fowler (editor), ''War and Civilization, Selections from A Study of History'', with a preface by Toynbee (New York, Oxford University Press 1950) *Introduction and translations, ''Twelve Men of Action in Greco-Roman History'' (Boston, Beacon Press 1952). Extracts from

''A Study of History''

**Vol VII: Universal States; Universal Churches **Vol VIII: Heroic Ages; Contacts between Civilizations in Space **Vol IX: Contacts between Civilizations in Time; Law and Freedom in History; The Prospects of the Western Civilization **Vol X: The Inspirations of Historians; A Note on Chronology ::(Oxford University Press 1954) *''An Historian's Approach to Religion'' (Oxford University Press 1956).

''A Study of History''

**Vol XI: Historical Atlas and Gazetteer ::(Oxford University Press 1959) *D. C. Somervell, ''A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-X in one volume'', with a new preface by Toynbee and new tables (Oxford University Press 1960)

**Vol XII: Reconsiderations ::(Oxford University Press 1961) *''Between

online from ACLS E-Books

Humanist among machines – As the dreams of Silicon Valley fill our world, could the dowdy historian Arnold Toynbee help prevent a nightmare?

' (March 2016), ''

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 – 22 October 1975) was an English

In his 1915 book ''Nationality & the War'', Toynbee argued in favor of creating a post-

In his 1915 book ''Nationality & the War'', Toynbee argued in favor of creating a post-

Michael Lang says that for much of the twentieth century,

In his best-known work, ''

Michael Lang says that for much of the twentieth century,

In his best-known work, ''

(examining the history of and reasons for the current hostility between east and west, and considering how non-westerners view the western world).

Canadian historians were especially receptive to Toynbee's work in the late historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

, a philosopher of history

Philosophy of history is the philosophical study of history and its discipline. The term was coined by French philosopher Voltaire.

In contemporary philosophy a distinction has developed between ''speculative'' philosophy of history and ''critic ...

, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

and King's College London. From 1918 to 1950, Toynbee was considered a leading specialist on international affairs

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such a ...

; from 1924 to 1954 he was the Director of Studies at Chatham House

Chatham House, also known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is an independent policy institute headquartered in London. Its stated mission is to provide commentary on world events and offer solutions to global challenges. It is ...

, in which position he also produced 34 volumes of the ''Survey of International Affairs,'' a "bible" for international specialists in Britain.

He is best known for his 12-volume ''A Study of History

''A Study of History'' is a 12-volume universal history by the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee, published from 1934 to 1961. It received enormous popular attention but according to historian Richard J. Evans, "enjoyed only a brief vogue befo ...

'' (1934–1961). With his prodigious output of papers, articles, speeches and presentations, and numerous books translated into many languages, Toynbee was a widely read and discussed scholar in the 1940s

File:1940s decade montage.png, Above title bar: events during World War II (1939–1945): From left to right: Troops in an LCVP landing craft approaching Omaha Beach on D-Day; Adolf Hitler visits Paris, soon after the Battle of France; The Ho ...

and 1950s

The 1950s (pronounced nineteen-fifties; commonly abbreviated as the "Fifties" or the " '50s") (among other variants) was a decade that began on January 1, 1950, and ended on December 31, 1959.

Throughout the decade, the world continued its re ...

.

Biography

Toynbee (born inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

on 14 April 1889) was the son of Harry Valpy Toynbee (1861–1941), secretary of the Charity Organization Society

The Charity Organisation Societies were founded in England in 1869 following the ' Goschen Minute' that sought to severely restrict outdoor relief distributed by the Poor Law Guardians. In the early 1870s a handful of local societies were formed w ...

, and his wife Sarah Edith Marshall (1859–1939); his sister Jocelyn Toynbee

Jocelyn Mary Catherine Toynbee, (3 March 1897 – 31 December 1985) was an English archaeologist and art historian. "In the mid-twentieth century she was the leading British scholar in Roman artistic studies and one of the recognized authoriti ...

was an archaeologist and art historian. Toynbee was the grandson of Joseph Toynbee

Joseph Toynbee FRS (30 December 1815

Another son, Harry Valpy Toynbee (1861–1941), was the father of universal historian Arnold J. Toynbee, and archaeologist and art historian Jocelyn Toynbee.

He died on 7 July 1866, at 18, Saville Row, M ...

, nephew of the 19th-century economist Arnold Toynbee (1852–1883) and descendant of prominent British intellectuals for several generations. He won scholarships to Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

and Balliol College, Oxford ('' literae humaniores'', 1907–1911), and studied briefly at the British School at Athens, an experience that influenced the genesis of his philosophy about the decline of civilisations.

In 1912 he became a tutor and fellow in ancient history at Balliol College, and in 1915 he began working for the intelligence department of the British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreig ...

. After serving as a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 he served as professor of Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and modern Greek studies at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

. It was here that Toynbee was appointed to the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature at King's College, although he would ultimately resign following a controversial academic dispute with the professoriate of the College. In 1921 and 1922 he was the '' Manchester Guardian'' correspondent during the Greco-Turkish War, an experience that resulted in the publication of ''The Western Question in Greece and Turkey''. In 1925 he became research professor of international history at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

and director of studies at the Royal Institute of International Affairs

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ci ...

in London. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA), the United Kingdoms national academy for the humanities and social sciences, in 1937.

His first marriage was to Rosalind Murray

Rosalind Murray (1890–1967, aged 76-77) was a British-born writer and novelist known for ''The Happy Tree'' and ''The Leading Note''.

Murray's parents were the classical scholar Gilbert Murray (1866-1957) and Lady Mary Henrietta Howard (1865� ...

(1890–1967), daughter of Gilbert Murray

George Gilbert Aimé Murray (2 January 1866 – 20 May 1957) was an Australian-born British classical scholar and public intellectual, with connections in many spheres. He was an outstanding scholar of the language and culture of Ancient Greece ...

, in 1913; they had three sons, of whom Philip Toynbee

Theodore Philip Toynbee (25 June 1916 – 15 June 1981) was a British writer and communist. He wrote experimental novels, and distinctive verse novels, one of which was an epic called ''Pantaloon'', a work in several volumes, only some of whi ...

was the second. They divorced in 1946; Toynbee then married his research assistant, Veronica M. Boulter (1893-1980), in the same year. He died on 22 October 1975, age 86.

Views on the post-World War I peace settlement and geopolitical situation

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

peace settlement

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surrend ...

based on the principle of nationality

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a ''national'', of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the ...

. In Chapter IV of his 1916 book

A book is a medium for recording information in the form of writing or images, typically composed of many pages (made of papyrus, parchment, vellum, or paper) bound together and protected by a cover. The technical term for this physi ...

''The New Europe: Essays in Reconstruction'', Toynbee criticized the concept of natural borders. Specifically, Toynbee criticized this concept as providing a justification for launching additional wars so that countries can attain their natural borders. Toynbee also pointed out how once a country attained one set of natural borders, it could subsequently aim to attain another, further set of natural borders; for instance, the German Empire set its western natural border at the Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

in 1871 but during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, some Germans began to advocate for even more western natural borders—specifically ones that extend all of the way up to Calais and the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

—conveniently justifying the permanent German retention of those Belgian and French territories that Germany had just conquered during World War I. As an alternative to the idea of natural borders, Toynbee proposes making free trade, partnership, and cooperation between various countries with interconnected economies considerably easier so that there would be less need for countries to expand even further—whether to their natural borders or otherwise. In addition, Toynbee advocated making national borders based more on the principle of national self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

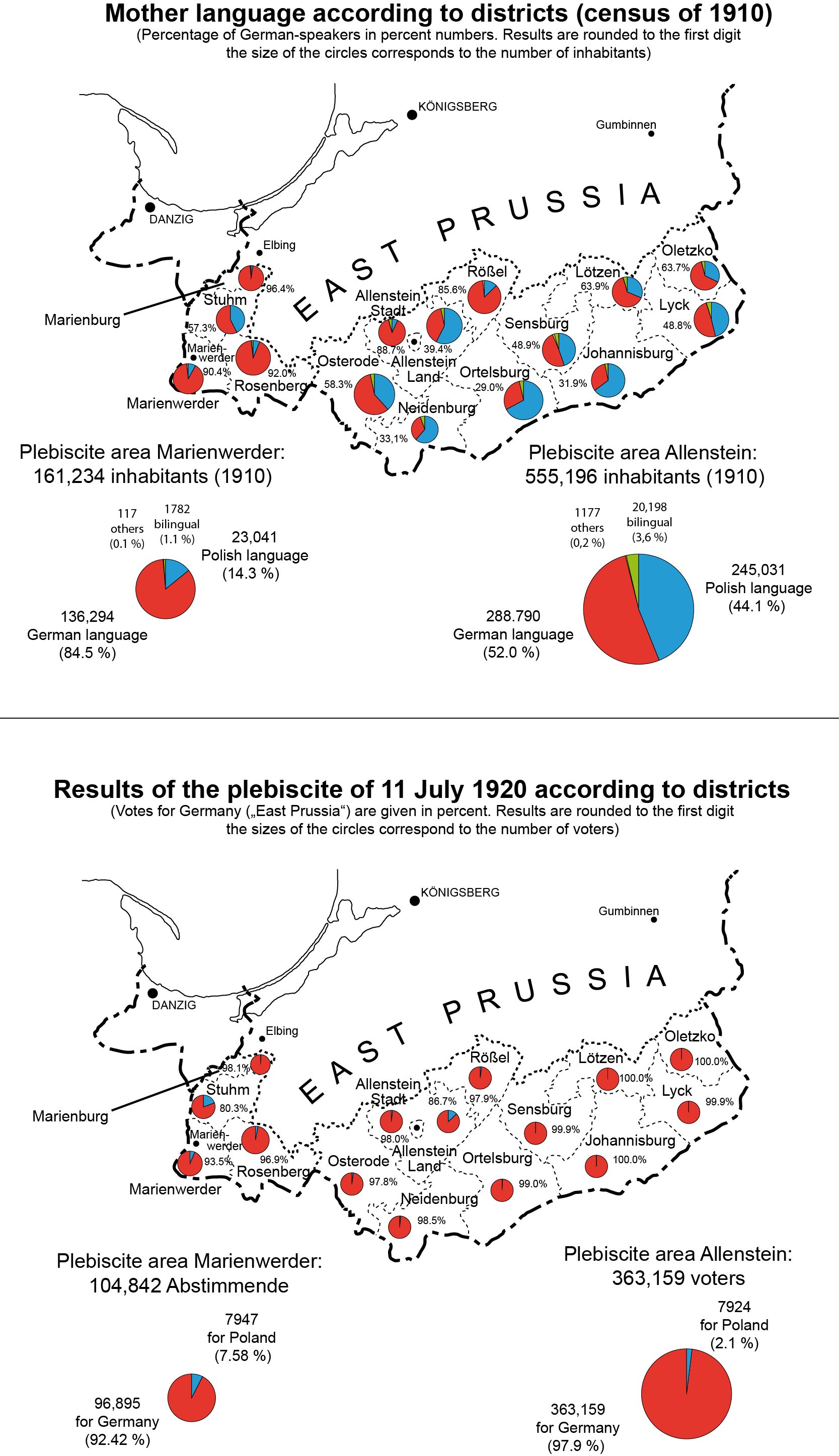

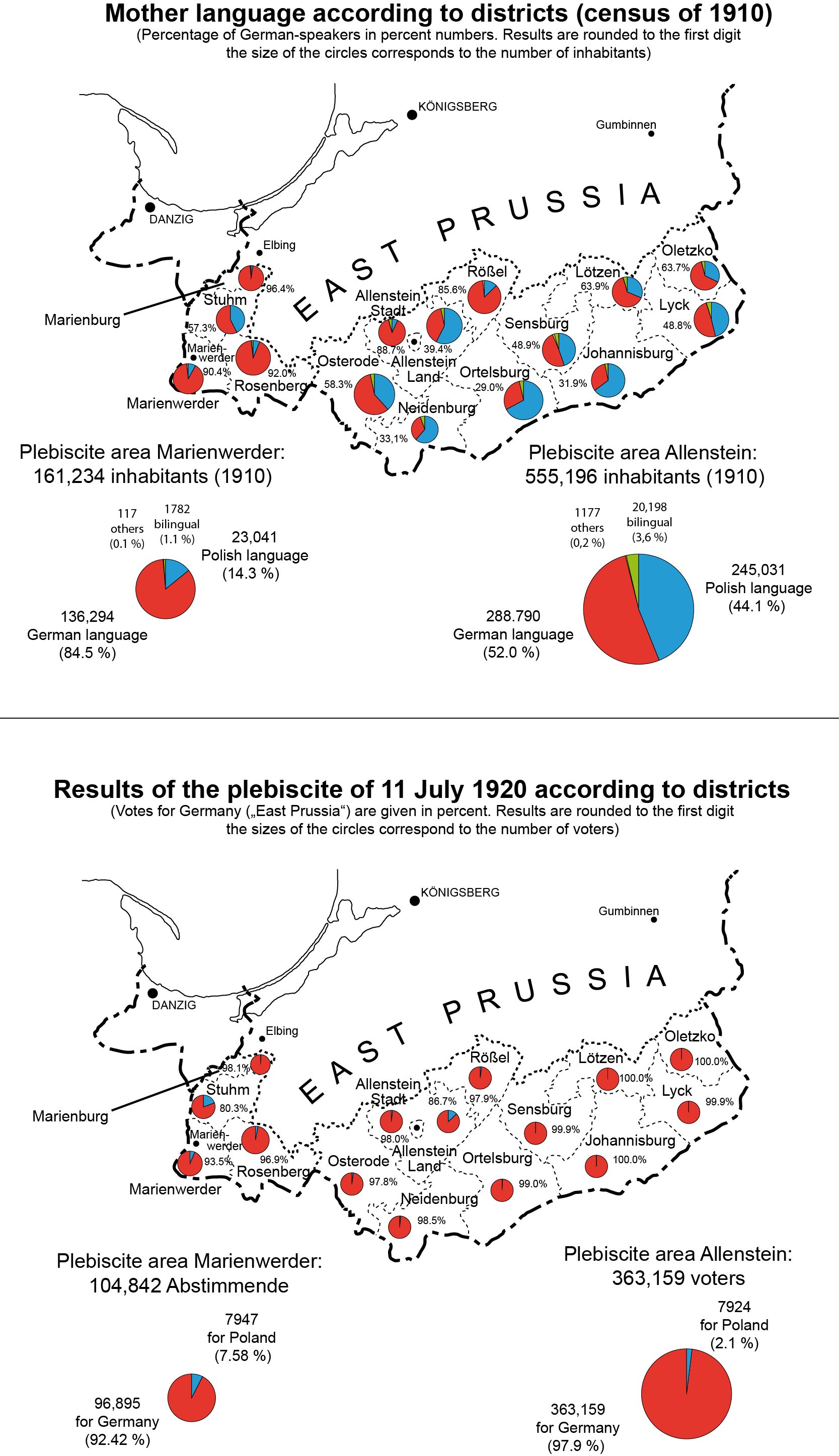

—as in, based on which country the people in a particular area or territory actually wanted to live in. (This principle was in fact indeed sometimes (albeit inconsistently) followed in the post-World War I peace settlement with the various plebiscites

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

that were conducted in the twenty years after the end of World War I--specifically in Schleswig, Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

, Masuria, Sopron

Sopron (; german: Ödenburg, ; sl, Šopron) is a city in Hungary on the Austrian border, near Lake Neusiedl/Lake Fertő.

History

Ancient times-13th century

When the area that is today Western Hungary was a province of the Roman Empire, a ...

, Carinthia, and the Saar—in order to determine the future sovereignty and fate of these territories.)

In ''Nationality & the War'', Toynbee offered various elaborate proposals and predictions for the future of various countries—both European and non-European. In regards to the Alsace-Lorraine dispute between France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, for instance, Toynbee proposed a series of plebiscites to determine its future fate—with Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

voting as a single unit in this plebiscite due to its interconnected nature. Toynbee likewise proposed a plebiscite in Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sc ...

to determine its future fate, with him arguing that the linguistic line might make the best new German-Danish border there (indeed, ultimately a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

was held in Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

in 1920). In regards to Poland, Toynbee advocated for the creation of an autonomous Poland under Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

rule (specifically a Poland in a federal relationship with Russia and that has a degree of home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

and autonomy that is at least comparable to that of the Austrian Poles) that would have put the Russian, German, and Austrian Poles under one sovereignty and government. Toynbee argued that Polish unity would be impossible in the event of an Austro-German victory in World War I since a victorious Germany would be unwilling to transfer its own Polish territories (which it views as strategically important and still hopes to Germanize) to an autonomous or newly independent Poland. Toynbee also proposed giving most of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

, Posen Province, and western Galicia to this autonomous Poland and suggested holding a plebiscite in Masuria

Masuria (, german: Masuren, Masurian: ''Mazurÿ'') is a ethnographic and geographic region in northern and northeastern Poland, known for its 2,000 lakes. Masuria occupies much of the Masurian Lake District. Administratively, it is part of the ...

(as indeed ultimately occurred in 1920 with the Masurian plebiscite) while allowing Germany to keep all of West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

, including the Polish parts that later became known as the Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor (german: Polnischer Korridor; pl, Pomorze, Polski Korytarz), also known as the Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, easter ...

(while, of course, making Danzig a free city that the autonomous Poland would be allowed to use). In regards to Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Toynbee proposed having Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

give up Galicia to Russia and an enlarged autonomous Russian Poland, give up Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

and Bukovina to Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, give up Trentino

Trentino ( lld, Trentin), officially the Autonomous Province of Trento, is an autonomous province of Italy, in the country's far north. The Trentino and South Tyrol constitute the region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, an autonomous region ...

(but not Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into prov ...

or South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous area, Autonomous Provinces of Italy, province

, image_skyline = ...

) to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and give up Bosnia, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, and Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

so that newly independent states can be formed there. Toynbee also advocated allowing Austria to keep Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic since ...

due to the strategic location of its Sudeten Mountain ridges and allowing Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

to keep Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

. Toynbee also advocated splitting Bessarabia between Russia and Romania, with Russia keeping the Budjak

Budjak or Budzhak ( Bulgarian and Ukrainian: Буджак; ro, Bugeac; Gagauz and Turkish: ''Bucak''), historically part of Bessarabia until 1812, is a historical region in Ukraine and Moldova. Lying along the Black Sea between the Danube ...

while Romania would acquire the rest of Bessarabia. Toynbee argued that a Romanian acquisition of the Budjak would be pointless due to its non-Romanian population and due to it providing little value for Romania; however, Toynbee did endorse Romanian use of the Russian port of Odessa, which would see its trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

traffic double in such a scenario.

In regards to Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

(aka ''Little Russia

Little Russia (russian: Малороссия/Малая Россия, Malaya Rossiya/Malorossiya; uk, Малоросія/Мала Росія, Malorosiia/Mala Rosiia), also known in English as Malorussia, Little Rus' (russian: Малая Ру� ...

''), Toynbee rejected both home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

and a federal solution for Ukraine. Toynbee's objection to the federal solution stemmed from his fear that a federated Russia would be too divided to have a unifying center of gravity and would thus be at risk of fragmentation and breaking up just like the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

previously did for a time during its own civil war. In place of autonomy, Toynbee proposed making the Ukrainian language

Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an East Slavic language of the Indo-European language family. It is the native language of about 40 million people and the official state lan ...

co-official in the Great Russian parts of the Russian Empire so that Ukrainians (or Little Russians) could become members of the Russian body politic as Great Russians' peers rather than as Great Russians' inferiors. Toynbee also argued that if the Ukrainian language will not be able to become competitive with Russian even if the Ukrainian language will be given official status in Russia, then this would prove once and for all the superior vitality of the Russian language (which, according to Toynbee, was used to write great literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

while the Ukrainian language was only used to write peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasant ...

ballads

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or '' ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

).

In regards to future Russian expansion, Toynbee endorsed the idea of Russia conquering Outer Mongolia and the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hydr ...

, arguing the Russia could improve and revitalize these territories just like the United States of America did for the Mexican Cession territories (specifically Nuevo Mexico and Alta California) when it conquered these territories from Mexico in the Mexican-American War back in 1847 (a conquest that Toynbee noted was widely criticized at the time, but which eventually became viewed as being a correct move on the part of the United States). Toynbee also endorsed the idea of having Russia annex both Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

and the Armenian Vilayets of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

while rejecting the idea of a Russo-British partition of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

as being impractical due to it being incapable of satisfying either Britain's or Russia's interests in Persia–with Toynbee thus believing that a partition of Persia would merely inevitably result in war between Britain and Russia. Instead, Toynbee argues for (if necessary, with foreign assistance) the creation of a strong, independent, central government in Persia that would be capable of both protecting its own interests and protecting the interests of both British and Russia while also preventing both of these powers from having imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

and predatory designs on Persia. In addition, in the event of renewed trouble and unrest in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

(which Toynbee viewed as only a matter of time), Toynbee advocated partitioning Afghanistan between Russia and British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

roughly along the path of the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and western Afghanistan, Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Province ...

. A partition of Afghanistan along these lines would result in Afghan Turkestan being unified with the predominantly Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging t ...

of Russian Central Asia

Russian Turkestan (russian: Русский Туркестан, Russkiy Turkestan) was the western part of Turkestan within the Russian Empire’s Central Asian territories, and was administered as a Krai or Governor-Generalship. It comprised the o ...

as well as with the Afghan Pashtuns being reunified with the Pakistani Pashtuns within British India. Toynbee viewed the Hindu Kush as being an ideal and impenetrable frontier between Russia and British India that would be impossible for either side to cross through and that would thus be great at providing security (and protection against aggression by the other side) for both sides.

Academic and cultural influence

Michael Lang says that for much of the twentieth century,

In his best-known work, ''

Michael Lang says that for much of the twentieth century,

In his best-known work, ''A Study of History

''A Study of History'' is a 12-volume universal history by the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee, published from 1934 to 1961. It received enormous popular attention but according to historian Richard J. Evans, "enjoyed only a brief vogue befo ...

'', published 1934–1961, Toynbee

...examined the rise and fall of 26 civilisations in the course of''A Study of History'' was both a commercial and academic phenomenon. In the U.S. alone, more than seven thousand sets of the ten-volume edition had been sold by 1955. Most people, including scholars, relied on the very clear one-volume abridgement of the first six volumes byhuman history Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ..., and he concluded that they rose by responding successfully to challenges under the leadership of creative minorities composed of elite leaders.

Somervell Somervell may refer to:

People

* Alexander Somervell (1796-1854), Texan soldier who led the Somervell Expedition into Mexico

* Arthur Somervell (1863–1937), British composer

* Brehon B. Somervell (1892–1955), American general

* D. C. Somerv ...

, which appeared in 1947; the abridgement sold over 300,000 copies in the U.S. The press printed innumerable discussions of Toynbee's work, not to mention there being countless lectures and seminars. Toynbee himself often participated. He appeared on the cover of ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' magazine in 1947, with an article describing his work as "the most provocative work of historical theory written in England since Karl Marx's ''Capital''", and was a regular commentator on BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...1940s

File:1940s decade montage.png, Above title bar: events during World War II (1939–1945): From left to right: Troops in an LCVP landing craft approaching Omaha Beach on D-Day; Adolf Hitler visits Paris, soon after the Battle of France; The Ho ...

. The Canadian economic historian Harold Adams Innis (1894–1952) was a notable example. Following Toynbee and others (Spengler, Kroeber, Sorokin, Cochrane), Innis examined the flourishing of civilisations in terms of administration of empires and media of communication.

Toynbee's overall theory was taken up by some scholars, for example, Ernst Robert Curtius

Ernst Robert Curtius (; 14 April 1886 – 19 April 1956) was a German literary scholar, philologist, and Romance language literary critic, best known for his 1948 study ''Europäische Literatur und Lateinisches Mittelalter'', translated in Eng ...

, as a sort of paradigm in the post-war period. Curtius wrote as follows in the opening pages of ''European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages'' (1953 English translation), following close on Toynbee, as he sets the stage for his vast study of medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functione ...

literature. Curtius wrote, "How do cultures, and the historical entities which are their media, arise, grow and decay? Only a comparative morphology with exact procedures can hope to answer these questions. It was Arnold J. Toynbee who undertook the task."

After 1960, Toynbee's ideas faded both in academia and the media, to the point of seldom being cited today. In general, historians pointed to his preference of myths, allegories, and religion over factual data. His critics argued that his conclusions are more those of a Christian moralist than of a historian. In his 2011 article for the ''Journal of History'' titled "Globalization and Global History in Toynbee," Michael Lang wrote:

:To many world historians today, Arnold J. Toynbee is regarded like an embarrassing uncle at a house party. He gets a requisite introduction by virtue of his place on the family tree, but he is quickly passed over for other friends and relatives.

However, his work continued to be referenced by some classical historians, because "his training and surest touch is in the world of classical antiquity." His roots in classical literature are also manifested by similarities between his approach and that of classical historians such as Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

and Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

. Comparative history

Comparative history is the comparison of different societies which existed during the same time period or shared similar cultural conditions.

The comparative history of societies emerged as an important specialty among intellectuals in the Enlight ...

, by which his approach is often categorised, has been in the doldrums.

Political influence in foreign policy

While the writing of the Study was under way, Toynbee produced numerous smaller works and served as director of foreign research of the Royal Institute of International Affairs (1939–43) and director of the research department of the Foreign Office (1943–46); he also retained his position at the London School of Economics until his retirement in 1956.Toynbee worked for the Political Intelligence Department of the

British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreig ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and served as a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was director of studies at Chatham House

Chatham House, also known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is an independent policy institute headquartered in London. Its stated mission is to provide commentary on world events and offer solutions to global challenges. It is ...

, Balliol College, Oxford University, 1924–43. Chatham House conducted research for the British Foreign Office and was an important intellectual resource during World War II when it was transferred to London. With his research assistant, Veronica M. Boulter, Toynbee was co-editor of the RIIA's annual ''Survey of International Affairs,'' which became the "bible" for international specialists in Britain.

Meeting with Adolf Hitler

While on a visit in Berlin in 1936 to address the Nazi Law Society, Toynbee was invited to a private interview withAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

at Hitler's request. During the interview, which was held a day before Toynbee delivered his lecture, Hitler emphasized his limited expansionist aim of building a greater German nation, and his desire for British understanding and co-operation with Nazi Germany. Hitler also suggested Germany could be an ally to Britain in the Asia-Pacific region if Germany's Pacific colonial empire were restored to her. Toynbee believed that Hitler was sincere and endorsed Hitler's message in a confidential memorandum for the British prime minister and foreign secretary.

Toynbee presented his lecture in English, but copies of it were circulated in German by Nazi officials, and it was warmly received by his Berlin audience who appreciated its conciliatory tone. Tracy Philipps

James Erasmus Tracy Philipps (20 November 1888 – 21 July 1959) was a British public servant. Philipps was, in various guises, a soldier, colonial administrator, traveller, journalist, propagandist, conservationist, and secret agent. He served ...

, a British 'diplomat' stationed in Berlin at the time, later informed Toynbee that it 'was an eager topic of discussion everywhere'. Back home, some of Toynbee's colleagues were dismayed by his attempts at managing Anglo-German relations.

Russia

Toynbee was troubled by the Russian Revolution since he saw Russia as a non-Western society and the revolution as a threat to Western society. However, in 1952, he argued that theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

had been a victim of Western aggression. He portrayed the Cold War as a religious competition that pitted a Marxist materialist heresy against the West's spiritual Christian heritage, which had already been foolishly rejected by a secularised West. A heated debate ensued, and an editorial in ''The Times'' promptly attacked Toynbee for treating communism as a "spiritual force".

Greece and the Middle East

Toynbee was a leading analyst of developments in the Middle East. His support for Greece and hostility to the Turks during World War I had gained him an appointment to the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History at King's College, University of London. However, after the war he changed to a pro-Turkish position, accusing Greece's military government in occupied Turkish territory of atrocities and massacres. This earned him the enmity of the wealthy Greeks who had endowed the chair, and in 1924 he was forced to resign the position. His stance during World War I reflected less sympathy for the Arab cause and took a pro-Zionist outlook. Toynbee investigatedZionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

in 1915 at the Information Department of the Foreign Office, and in 1917 he published a memorandum with his colleague Lewis Namier

Sir Lewis Bernstein Namier (; 27 June 1888 – 19 August 1960) was a British historian of Polish-Jewish background. His best-known works were ''The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III'' (1929), ''England in the Age of the Ameri ...

which supported exclusive Jewish political rights in Palestine. He expressed support for Jewish immigration to Palestine, which he believed had "begun to recover its ancient prosperity" as a result. In 1922, however, he was influenced by the Palestine Arab delegation which was visiting London, and began to adopt their views. His subsequent writings reveal his changing outlook on the subject, and by the late 1940s he had moved away from the Zionist cause and toward the Arab camp; Toynbee came to be known, by his own admission, as "the Western spokesman for the Arab cause."

The views Toynbee expressed in the 1950s continued to oppose the formation of a Jewish state, partly out of his concern that it would increase the risk of a nuclear confrontation. However, as a result of Toynbee's debate in January 1961 with Yaakov Herzog

Yaakov Herzog ( he, יעקב דוד הרצוג, 11 December 1921 – 9 March 1972) was an Irish-born Israeli diplomat.

Biography

Yaakov Herzog was born in Dublin, Ireland. His father was Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, the second Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of ...

, the Israeli ambassador to Canada, Toynbee softened his view and called on Israel to fulfill its special "mission to make contributions to worldwide efforts to prevent the outbreak of nuclear war." In his article "Jewish Rights in Palestine", he challenged the views of the editor of the Jewish Quarterly Review

''The Jewish Quarterly Review'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering Jewish studies. It is published by the University of Pennsylvania Press on behalf of the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies (University of Pe ...

, historian and talmudic scholar Solomon Zeitlin

Solomon Zeitlin, שְׁניאור זלמן צײטלין, Шломо Цейтлин ''Shlomo Cejtlin'' (''Tseitlin, Tseytlin'') (28 May 1886 or 31 May 1892, in Chashniki, Vitebsk Governorate (now in Vitebsk Region) in Russia – 28 December 1976, i ...

, who published his rebuke, "Jewish Rights in Eretz Israel (Palestine)" in the same issue. Toynbee maintained, among other contentions, that the Jewish people have neither historic nor legal claims to Palestine, stating that the Arab "population's human rights to their homes and property over-ride all other rights in cases where claims conflict." Toynbee did ultimately concede that Jews, "being the only surviving representatives of any of the pre-Arab inhabitants of Palestine, have a further claim to a national home in Palestine," but that such a claim is valid "only in so far as it can be implemented without injury to the rights and to the legitimate interests of the native Arab population of Palestine."

Negative views of Jews and Judaism: The "Toynbee heresy" and the Jew as "fossil"

Toynbee's views on Middle East politics have often been linked with the negative evaluation of Jews and Judaism Toynbee expressed in his discussion of Jews and Jewish civilization more generally. In a famous speech entitled "the Toynbee heresy,"Abba Eban

Abba Solomon Meir Eban (; he, אבא אבן ; born Aubrey Solomon Meir Eban; 2 February 1915 – 17 November 2002) was an Israeli diplomat and politician, and a scholar of the Arabic and Hebrew languages.

During his career, he served as For ...

, an academic of brilliant potential before he became a diplomat, analyzed the uniformly negative role and associations Toynbee assigned to Judaism and Jews in his history of civilization as a whole, and the degree to which this was in turn premised on a belief in the superiority of Christianity to Judaism. Eban noted how Toynbee used the term "Judaic" to describe what Toynbee considers to be instantiations of "extreme brutality," even, or especially, in instances where Jews themselves are in no way involved, such as the Gothic persecution of the Christians. More generally, Eban observed throughout the first eight volumes of his civilization series, Toynbee has a habit of referring to the Jewish people as a "fossil remnant," a term Toynbee does not define but which emerges in his writing as expressing the idea that Judaism, a religion for Toynbee is defined by its "fanaticism," its "provincialism," and its "exclusivity," exists solely as a vehicle to deliver the superior civilization and moral code of Christianity.

As Eban points out, Toynbee's reading of Jews and Judaism through a Christian lens colors his view of Zionism and the state of Israel. By characterizing Judaism as a morally primitive belief-system based on the idea that Jews are the "master race," and then asserting that Jews' claim to Israel is based on this premise, Toynbee figures Zionism as "kindred to Nazism." On the other hand, Toynbee argues that by failing to accept their fate as a Diaspora community and trying instead to replace the "traditional Jewish hope of an eventual Restoration of Israel to Palestine on God's initiative through the agency of a divinely inspired Messiah," Zionist Jews have the same "impious" relationship to their religion as Communists do to Christianity. Having thus equated Zionism with both Nazism and Communism, Toynbee asserts:

Dialogue with Daisaku Ikeda

In 1972, Toynbee met withDaisaku Ikeda

is a Japanese Buddhist philosopher, educator, author, and nuclear disarmament advocate. He served as the third president and then honorary president of the Soka Gakkai, the largest of Japan's new religious movements. Ikeda is the founding pre ...

, president of Soka Gakkai International

Soka Gakkai International (SGI) is an international Nichiren Buddhist organisation founded in 1975 by Daisaku Ikeda, as an umbrella organization of Soka Gakkai, which declares approximately 12 million adherents in 192 countries and territorie ...

(SGI), who condemned the "demonic nature" of the use of nuclear weapons under any circumstances. Toynbee had the view that the atomic bomb was an invention that had caused warfare to escalate from a political scale to catastrophic proportions and threatened the very existence of the human race. In his dialogue with Ikeda, Toynbee stated his worry that humankind would not be able to strengthen ethical behaviour and achieve self-mastery "in spite of the widespread awareness that the price of failing to respond to the moral challenge of the atomic age may be the self-liquidation of our species."

The two men first met on 5 May 1972 in London. In May 1973, Ikeda again flew to London to meet with Toynbee for 40 hours over a period of 10 days. Their dialogue and ongoing correspondence culminated in the publication of ''Choose Life'', a record of their views on critical issues confronting humanity. The book has been published in 24 languages to date. Toynbee also wrote the foreword to the English edition of Ikeda's best-known book, ''The Human Revolution'', which has sold more than 7 million copies worldwide.

Toynbee being "paid well" for the interviews with Ikeda raised criticism. In 1984 his granddaughter Polly Toynbee wrote a critical article for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' on meeting Daisaku Ikeda; she begins writing: "On the long flight to Japan, I read for the first time my grandfather's posthumously, published book, ''Choose Life – A Dialogue'', a discussion between himself and a Japanese Buddhist leader called Daisaku Ikeda. My grandfather ..was 85 when the dialogue was recorded, a short time before his final incapacitating stroke. It is probably the book among his works most kindly left forgotten – being a long discursive ramble between the two men over topics from sex education to pollution and war."

An exhibition celebrating the 30th anniversary of Toynbee and Ikeda's first meeting was presented in SGI's centers around the world in 2005, showcasing contents of the dialogues between them, as well as Ikeda's discussions for peace with over 1,500 of the world's scholars, intellects, and activists. Original letters Toynbee and Ikeda exchanged were also displayed.

Challenge and response

With the civilisations as units identified, he presented the history of each in terms of challenge-and-response, sometimes referred to as theory about the law of challenge and response. Civilizations arose in response to some set of challenges of extreme difficulty, when "creative minorities" devised solutions that reoriented their entire society. Challenges and responses were physical, as when the Sumerians exploited the intractable swamps of southernIraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

by organising the Neolithic inhabitants into a society capable of carrying out large-scale irrigation projects; or social, as when the Catholic Church resolved the chaos of post-Roman Europe by enrolling the new Germanic kingdoms in a single religious community. When a civilisation responded to challenges, it grew. Civilizations disintegrate when their leaders stopped responding creatively, and the civilisations then sank owing to nationalism, militarism, and the tyranny of a despotic minority. According to an Editor's Note in an edition of Toynbee's ''A Study of History,'' Toynbee believed that societies always die from suicide or murder rather than from natural causes, and nearly always from suicide. He sees the growth and decline of civilisations as a spiritual process, writing that "Man achieves civilization, not as a result of superior biological endowment or geographical environment, but as a response to a challenge in a situation of special difficulty which rouses him to make a hitherto unprecedented effort."

Toynbee Prize Foundation

Named after Arnold J. Toynbee, the oynbee PrizeFoundation was chartered in 1987 'to contribute to the development of theThe Toynbee Prize is an honorary award, recognising social scientists for significantsocial sciences Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of so ..., as defined from a broad historical view of human society and of human and social problems.' In addition to awarding the Toynbee Prize, the foundation sponsors scholarly engagement with global history through sponsorship of sessions at the annual meeting of theAmerican Historical Association The American Historical Association (AHA) is the oldest professional association of historians in the United States and the largest such organization in the world. Founded in 1884, the AHA works to protect academic freedom, develop professional s ..., of international conferences, of the journal ''New Global Studies'' and of the Global History Forum.

academic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

and public contributions to humanity. Currently, it is awarded every other year for work that makes a significant contribution to the study of global history. The recipients have been Raymond Aron

Raymond Claude Ferdinand Aron (; 14 March 1905 – 17 October 1983) was a French philosopher, sociologist, political scientist, historian and journalist, one of France's most prominent thinkers of the 20th century.

Aron is best known for his 19 ...

, Lord Kenneth Clark, Sir Ralf Dahrendorf

Ralf Gustav Dahrendorf, Baron Dahrendorf, (1 May 1929 – 17 June 2009) was a German-British sociologist, philosopher, political scientist and liberal politician. A class conflict theorist, Dahrendorf was a leading expert on explaining and a ...

, Natalie Zemon Davis, Albert Hirschman

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Albert ...

, George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

, Bruce Mazlish Bruce Mazlish (September 15, 1923 – November 27, 2016) was an American historian who was a professor in the Department of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work focused on historiography and philosophy of history, history ...

, John McNeill, William McNeill, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and lit ...

, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Barbara Ward

Barbara Mary Ward, Baroness Jackson of Lodsworth, (23 May 1914 – 31 May 1981) was a British economist and writer interested in the problems of developing countries. She urged Western governments to share their prosperity with the rest of th ...

, Lady Jackson, Sir Brian Urquhart, Michael Adas

Michael Adas (born 4 February 1943 in Detroit, Michigan) is an American historian and currently the Abraham E. Voorhees Professor of History at Rutgers University. He specializes in the history of technology, the history of anticolonialism and ...

, Christopher Bayly

Sir Christopher Alan Bayly, FBA, FRSL (18 May 1945 – 18 April 2015) was a British historian specialising in British Imperial, Indian and global history. From 1992 to 2013, he was Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History at t ...

, and Jürgen Osterhammel

Jürgen Osterhammel (born 1952 in Wipperfürth, North Rhine-Westphalia) is a German historian specialized in Chinese and world history. He is professor emeritus at the University of Konstanz.

Academia

Osterhammel started his academic career as ...

.

Toynbee's works

*''The Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation, with a speech delivered by Lord Bryce in the House of Lords'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1915) *''Nationality and the War'' (Dent 1915) *''The New Europe: Some Essays in Reconstruction, with an Introduction by theEarl of Cromer

Earl of Cromer is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, held by members of the Baring family, of German descent. It was created for Evelyn Baring, 1st Viscount Cromer, long time British Consul-General in Egypt. He had already been cr ...

'' (Dent 1915)Contributor, Greece

in ''The Balkans: A History of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Rumania, Turkey'', various authors (Oxford, Clarendon Press 1915)

''British View of the Ukrainian Question''

(Ukrainian Federation of U.S., New York, 1916) *Editor, '' The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Fallodon by Viscount Bryce, with a Preface by Viscount Bryce'' (Hodder & Stoughton and His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1916) *''The Destruction of Poland: A Study in German Efficiency'' (1916) *''The Belgian Deportations, with a statement by Viscount Bryce'' (T. Fisher Unwin 1917) *''The German Terror in Belgium: An Historical Record'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1917) *''The German Terror in France: An Historical Record'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1917) *''Turkey: A Past and a Future'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1917)

''The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilizations'' (Constable 1922)

*Introduction and translations, ''Greek Civilization and Character: The Self-Revelation of Ancient Greek Society'' (Dent 1924) *Introduction and translations, ''Greek Historical Thought from Homer to the Age of Heraclius, with two pieces newly translated by Gilbert Murray'' (Dent 1924) *Contributor, ''The Non-Arab Territories of the Ottoman Empire since the Armistice of 30 October 1918'', in H. W. V. Temperley (editor), ''A History of the Peace Conference of Paris'', Vol. VI (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the British Institute of International Affairs 1924) *''The World after the Peace Conference, Being an Epilogue to the "History of the Peace Conference of Paris" and a Prologue to the "Survey of International Affairs, 1920–1923"'' (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the British Institute of International Affairs 1925). Published on its own, but Toynbee writes that it was "originally written as an introduction to the Survey of International Affairs in 1920–1923, and was intended for publication as part of the same volume". *With Kenneth P. Kirkwood, ''Turkey'' (Benn 1926, in Modern Nations series edited by H. A. L. Fisher) *''The Conduct of British Empire Foreign Relations since the Peace Settlement'' (Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs 1928) *''A Journey to China, or Things Which Are Seen'' (Constable 1931) *Editor, ''British Commonwealth Relations, Proceedings of the First Unofficial Conference at Toronto, 11–21 September 1933'', with a foreword by Robert L. Borden (Oxford University Press under the joint auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs and the Canadian Institute of International Affairs 1934)

''A Study of History''

**Vol I: Introduction; The Geneses of Civilizations **Vol II: The Geneses of Civilizations **Vol III: The Growths of Civilizations ::(Oxford University Press 1934) *Editor, with J. A. K. Thomson, ''Essays in Honour of Gilbert Murray'' (George Allen & Unwin 1936)

''A Study of History''

** Vol IV: The Breakdowns of Civilizations ** Vol V: The Disintegrations of Civilizations **Vol VI: The Disintegrations of Civilizations ::(Oxford University Press 1939) * D. C. Somervell, ''A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-VI'', with a preface by Toynbee (Oxford University Press 1946) *''Civilization on Trial'' (Oxford University Press 1948) *''The Prospects of Western Civilization'' (New York, Columbia University Press 1949). Lectures delivered at Columbia University on themes from a then-unpublished part of ''A Study of History''. Published "by arrangement with Oxford University Press in an edition limited to 400 copies and not to be reissued". * Albert Vann Fowler (editor), ''War and Civilization, Selections from A Study of History'', with a preface by Toynbee (New York, Oxford University Press 1950) *Introduction and translations, ''Twelve Men of Action in Greco-Roman History'' (Boston, Beacon Press 1952). Extracts from

Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

and Polybius.

*''The World and the West'' (Oxford University Press 1953). Reith Lecture

The Reith Lectures is a series of annual BBC radio lectures given by leading figures of the day. They are commissioned by the BBC and broadcast on Radio 4 and the World Service. The lectures were inaugurated in 1948 to mark the historic contribu ...

s for 1952.''A Study of History''

**Vol VII: Universal States; Universal Churches **Vol VIII: Heroic Ages; Contacts between Civilizations in Space **Vol IX: Contacts between Civilizations in Time; Law and Freedom in History; The Prospects of the Western Civilization **Vol X: The Inspirations of Historians; A Note on Chronology ::(Oxford University Press 1954) *''An Historian's Approach to Religion'' (Oxford University Press 1956).

Gifford Lectures

The Gifford Lectures () are an annual series of lectures which were established in 1887 by the will of Adam Gifford, Lord Gifford. Their purpose is to "promote and diffuse the study of natural theology in the widest sense of the term – in o ...

, University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

, 1952–1953.

*D. C. Somervell, ''A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols VII-X'', with a preface by Toynbee (Oxford University Press 1957)

*''Christianity among the Religions of the World'' (New York, Scribner 1957; London, Oxford University Press 1958). Hewett Lectures, delivered in 1956.

*''Democracy in the Atomic Age'' (Melbourne, Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Australian Institute of International Affairs 1957). Dyason Lectures, delivered in 1956.

*''East to West: A Journey round the World'' (Oxford University Press 1958)

*''Hellenism: The History of a Civilization'' (Oxford University Press 1959, in Home University Library)

*With Edward D. Myers''A Study of History''

**Vol XI: Historical Atlas and Gazetteer ::(Oxford University Press 1959) *D. C. Somervell, ''A Study of History: Abridgement of Vols I-X in one volume'', with a new preface by Toynbee and new tables (Oxford University Press 1960)

**Vol XII: Reconsiderations ::(Oxford University Press 1961) *''Between

Oxus

The Amu Darya, tk, Amyderýa/ uz, Amudaryo// tg, Амударё, Amudaryo ps, , tr, Ceyhun / Amu Derya grc, Ὦξος, Ôxos (also called the Amu, Amo River and historically known by its Latin name or Greek ) is a major river in Central Asi ...

and Jumna'' (Oxford University Press 1961)

*''America and the World Revolution'' (Oxford University Press 1962). Public lectures delivered at the University of Pennsylvania, spring 1961.

*''The Economy of the Western Hemisphere'' (Oxford University Press 1962). Weatherhead Foundation Lectures delivered at the University of Puerto Rico, February 1962.

*''The Present-Day Experiment in Western Civilization'' (Oxford University Press 1962). Beatty Memorial Lectures delivered at McGill University, Montreal, 1961.

::''The three sets of lectures published separately in the UK in 1962 appeared in New York in the same year in one volume under the title America and the World Revolution and Other Lectures, Oxford University Press.''

*''Universal States'' (New York, Oxford University Press 1963). Separate publication of part of Vol VII of A Study of History.

*With Philip Toynbee

Theodore Philip Toynbee (25 June 1916 – 15 June 1981) was a British writer and communist. He wrote experimental novels, and distinctive verse novels, one of which was an epic called ''Pantaloon'', a work in several volumes, only some of whi ...

, ''Comparing Notes: A Dialogue across a Generation'' (Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1963). "Conversations between Arnold Toynbee and his son, Philip … as they were recorded on tape."

*''Between Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesNile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

'' (Oxford University Press 1965)

*''Hannibal's Legacy: The Hannibalic War's Effects on Roman Life''

**Vol I: Rome and Her Neighbours before Hannibal's Entry

**Vol II: Rome and Her Neighbours after Hannibal's Exit

::(Oxford University Press 1965)

*''Change and Habit: The Challenge of Our Time'' (Oxford University Press 1966). Partly based on lectures given at University of Denver

The University of Denver (DU) is a private research university in Denver, Colorado. Founded in 1864, it is the oldest independent private university in the Rocky Mountain Region of the United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Univ ...

in the last quarter of 1964, and at New College, Sarasota, Florida and the University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee in the first quarter of 1965.

*''Acquaintances'' (Oxford University Press 1967)

*''Between Maule and Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

'' (Oxford University Press 1967)

*Editor, ''Cities of Destiny'' (Thames & Hudson 1967)

*Editor and principal contributor, ''Man's Concern with Death'' (Hodder & Stoughton 1968)

*Editor, ''The Crucible of Christianity: Judaism, Hellenism and the Historical Background to the Christian Faith'' (Thames & Hudson 1969)

*''Experiences'' (Oxford University Press 1969)

*''Some Problems of Greek History'' (Oxford University Press 1969)

*''Cities on the Move'' (Oxford University Press 1970). Sponsored by the Institute of Urban Environment of the School of Architecture, Columbia University.

*''Surviving the Future'' (Oxford University Press 1971). Rewritten version of a dialogue between Toynbee and Professor Kei Wakaizumi of Kyoto Sangyo University: essays preceded by questions by Wakaizumi.

*With Jane Caplan, ''A Study of History'', new one-volume abridgement, with new material and revisions and, for the first time, illustrations (Oxford University Press and Thames & Hudson 1972)

*''Constantine Porphyrogenitus

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe Ka ...

and His World'' (Oxford University Press 1973)

*''Editor, Half the World: The History and Culture of China and Japan'' (Thames & Hudson 1973)

*''Toynbee on Toynbee: A Conversation between Arnold J. Toynbee and G. R. Urban'' (New York, Oxford University Press 1974)

*''Mankind and Mother Earth: A Narrative History of the World'' (Oxford University Press 1976), posthumous

* Richard L. Gage (editor), ''The Toynbee-Ikeda Dialogue: Man Himself Must Choose'' (Oxford University Press 1976), posthumous. The record of a conversation lasting several days.

* E. W. F. Tomlin (editor), ''Arnold Toynbee: A Selection from His Works'', with an introduction by Tomlin (Oxford University Press 1978), posthumous. Includes advance extracts from ''The Greeks and Their Heritages''.

*''The Greeks and Their Heritages'' (Oxford University Press 1981), posthumous

* Christian B. Peper (editor), ''An Historian's Conscience: The Correspondence of Arnold J. Toynbee and Columba Cary-Elwes, Monk of Ampleforth'', with a foreword by Lawrence L. Toynbee (Oxford University Press by arrangement with Beacon Press, Boston 1987), posthumous

*''The Survey of International Affairs'' was published by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Royal Institute of International Affairs between 1925 and 1977 and covered the years 1920–1963. Toynbee wrote, with assistants, the Pre-War Series (covering the years 1920–1938) and the War-Time Series (1938–1946), and contributed introductions to the first two volumes of the Post-War Series (1947–1948 and 1949–1950). His actual contributions varied in extent from year to year.

*A complementary series, ''Documents on International Affairs'', covering the years 1928–1963, was published by Oxford University Press between 1929 and 1973. Toynbee supervised the compilation of the first of the 1939–1946 volumes, and wrote a preface for both that and the 1947–1948 volume.

See also

*Toynbee tiles

The Toynbee tiles, also called Toynbee plaques, are messages of unknown origin found embedded in asphalt of streets in about two dozen major cities in the United States and four South American cities. Since the 1980s, several hundred tiles have ...

* Fernand Braudel

Fernand Braudel (; 24 August 1902 – 27 November 1985) was a French historian and leader of the Annales School. His scholarship focused on three main projects: ''The Mediterranean'' (1923–49, then 1949–66), ''Civilization and Capitalism'' ...

* Christopher Dawson

Christopher Henry Dawson (12 October 188925 May 1970) was a British independent scholar, who wrote many books on cultural history and Christendom. Dawson has been called "the greatest English-speaking Catholic historian of the twentieth century ...

* Will Durant

William James Durant (; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He became best known for his work '' The Story of Civilization'', which contains 11 volumes and details the history of eastern a ...

* Carroll Quigley

* Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best kno ...

* Eric Voegelin

Eric Voegelin (born Erich Hermann Wilhelm Vögelin, ; 1901–1985) was a German-American political philosopher. He was born in Cologne, and educated in political science at the University of Vienna, where he became an associate professor of poli ...

* World history

World history may refer to:

* Human history, the history of human beings

* History of Earth, the history of planet Earth

* World history (field), a field of historical study that takes a global perspective

* ''World History'' (album), a 1998 albu ...

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

*online from ACLS E-Books

Further reading

* Beacock, Ian.Humanist among machines – As the dreams of Silicon Valley fill our world, could the dowdy historian Arnold Toynbee help prevent a nightmare?

' (March 2016), ''

Aeon

The word aeon , also spelled eon (in American and Australian English), originally meant "life", "vital force" or "being", "generation" or "a period of time", though it tended to be translated as "age" in the sense of "ages", "forever", "timele ...

''

* Ben-Israel, Hedva. "Debates With Toynbee: Herzog

''Herzog'' (female ''Herzogin'') is a German hereditary title held by one who rules a territorial duchy, exercises feudal authority over an estate called a duchy, or possesses a right by law or tradition to be referred to by the ducal title. ...

, Talmon, Friedman", ''Israel Studies'', Spring 2006, Vol. 11 Issue 1, pp. 79–90

* Brewin, Christopher. "Arnold Toynbee, Chatham House, and Research in a Global Context", in David Long and Peter Wilson, eds. ''Thinkers of the Twenty Years' Crisis: Inter-War Idealism Reassessed'' (1995) pp. 277–302.

* Costello, Paul. ''World Historians and Their Goals: Twentieth-Century Answers to Modernism'' (1993). Compares Toynbee with H. G. Wells