Arab revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the

When Herbert Kitchener was Consul-General in

When Herbert Kitchener was Consul-General in

In June 1916, the British sent out a number of officials to assist the revolt in the Hejaz, most notably Colonel Cyril Wilson, Colonel Pierce C. Joyce, and Lt-Colonel Stewart Francis Newcombe.Murphy, p. 17. Herbert Garland was also involved. In addition, a French military mission commanded by Colonel

In June 1916, the British sent out a number of officials to assist the revolt in the Hejaz, most notably Colonel Cyril Wilson, Colonel Pierce C. Joyce, and Lt-Colonel Stewart Francis Newcombe.Murphy, p. 17. Herbert Garland was also involved. In addition, a French military mission commanded by Colonel  Lawrence obtained assistance from the

Lawrence obtained assistance from the

The year 1917 began well for the Hashemites when the Emir Abdullah and his Arab Eastern Army ambushed an Ottoman convoy led by Ashraf Bey in the desert, and captured £20,000 worth of gold coins that were intended to bribe the Bedouin into loyalty to the Sultan. Starting in early 1917, the Hashemite guerrillas began attacking the Hejaz railway.Murphy, pp. 39–43. At first, guerrilla forces commanded by officers from the Regular Army such as al-Misri, and by British officers such as Newcombe, Lieutenant Hornby and Major Herbert Garland focused their efforts on blowing up unguarded sections of the Hejaz railway. Garland was the inventor of the so-called "Garland mine", which was used with much destructive force on the Hejaz railway.Murphy, p. 43. In February 1917, Garland succeeded for the first time in destroying a moving locomotive with a mine of his own design. Around

The year 1917 began well for the Hashemites when the Emir Abdullah and his Arab Eastern Army ambushed an Ottoman convoy led by Ashraf Bey in the desert, and captured £20,000 worth of gold coins that were intended to bribe the Bedouin into loyalty to the Sultan. Starting in early 1917, the Hashemite guerrillas began attacking the Hejaz railway.Murphy, pp. 39–43. At first, guerrilla forces commanded by officers from the Regular Army such as al-Misri, and by British officers such as Newcombe, Lieutenant Hornby and Major Herbert Garland focused their efforts on blowing up unguarded sections of the Hejaz railway. Garland was the inventor of the so-called "Garland mine", which was used with much destructive force on the Hejaz railway.Murphy, p. 43. In February 1917, Garland succeeded for the first time in destroying a moving locomotive with a mine of his own design. Around

By the time of

By the time of  In 1918, the Arab cavalry gained in strength (as it seemed victory was at hand) and they were able to provide Allenby's army with intelligence on Ottoman army positions. They also harassed Ottoman supply columns, attacked small garrisons, and destroyed railway tracks. A major victory occurred on 27 September when an entire brigade of Ottoman, Austrian and German troops, retreating from Mezerib, was virtually wiped out in a battle with Arab forces near the village of Tafas (which the Turks had plundered during their retreat).Murphy, pp. 76–77. This led to the so-called Tafas massacre, in which Lawrence claimed in a letter to his brother to have issued a "no-prisoners" order, maintaining after the war that massacre was in retaliation for the earlier Ottoman massacre of the village of Tafas, and that he had at least 250 German and Austrian POWs together with an uncounted number of Turks lined up to be summarily shot. Lawrence later wrote in ''

In 1918, the Arab cavalry gained in strength (as it seemed victory was at hand) and they were able to provide Allenby's army with intelligence on Ottoman army positions. They also harassed Ottoman supply columns, attacked small garrisons, and destroyed railway tracks. A major victory occurred on 27 September when an entire brigade of Ottoman, Austrian and German troops, retreating from Mezerib, was virtually wiped out in a battle with Arab forces near the village of Tafas (which the Turks had plundered during their retreat).Murphy, pp. 76–77. This led to the so-called Tafas massacre, in which Lawrence claimed in a letter to his brother to have issued a "no-prisoners" order, maintaining after the war that massacre was in retaliation for the earlier Ottoman massacre of the village of Tafas, and that he had at least 250 German and Austrian POWs together with an uncounted number of Turks lined up to be summarily shot. Lawrence later wrote in ''

The

The

History of the Arab Revolt

(on

Arab Revolt

at PBS

T.E. Lawrence's Original Letters on Palestine

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

The Revolt in Arabia

by

Chariots of war: When T.E. Lawrence and his armored Rolls-Royces ruled the Arabian desert

', Brendan McAleer, 10 August 2017,

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I saw action between 29 October 1914 and 30 October 1918. The combatants were, on one side, the Ottoman Empire (including the majority of Kurdish tribes, a relative majority of Arabs, and Caucasian ''T ...

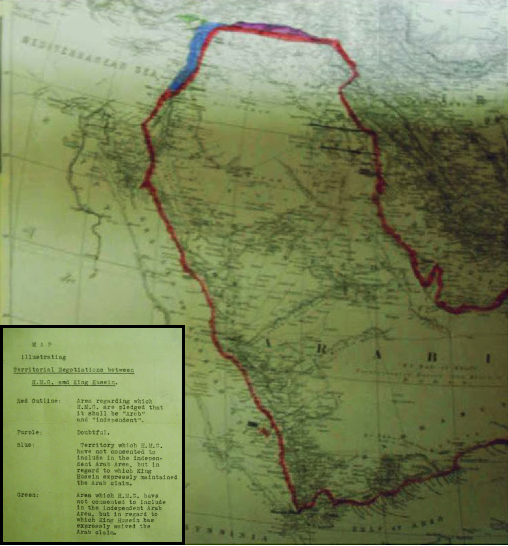

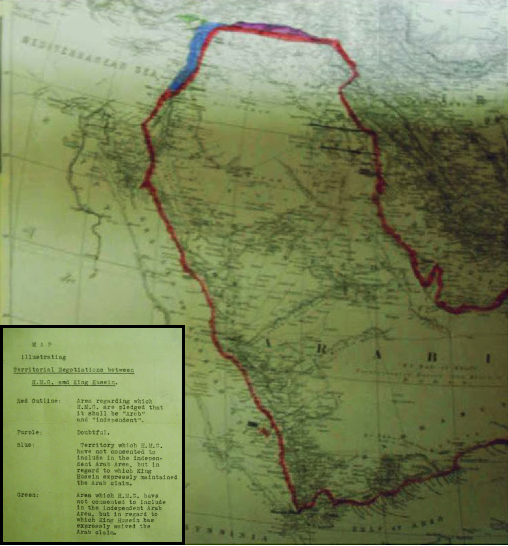

. On the basis of the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I in which the Government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif ...

, an agreement between the British government and Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ar, الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, al-Ḥusayn bin ‘Alī al-Hāshimī; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after procl ...

, the revolt was officially initiated at Mecca on June 10, 1916. The aim of the revolt was to create a single unified and independent Arab state stretching from Aleppo in Syria to Aden in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, which the British had promised to recognize.

The Sharifian Army led by Hussein and the Hashemites

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

, with military backing from the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning ...

, successfully fought and expelled the Ottoman military presence from much of the Hejaz and Transjordan. The rebellion eventually took Damascus and set up the Arab Kingdom of Syria, a short-lived monarchy led by Faisal, a son of Hussein.

Following the Sykes–Picot Agreement, the Middle East was later partitioned by the British and French into mandate territories rather than a unified Arab state, and the British reneged on their promise to support a unified independent Arab state.

Background

Therise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire

The rise of the Western notion of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire eventually caused the breakdown of the Ottoman ''millet'' concept. An understanding of the concept of nationhood prevalent in the Ottoman Empire, which was different from the c ...

dates from at least 1821. Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language a ...

has its roots in the Mashriq

The Mashriq ( ar, ٱلْمَشْرِق), sometimes spelled Mashreq or Mashrek, is a term used by Arabs to refer to the eastern part of the Arab world, located in Western Asia and eastern North Africa. Poetically the "Place of Sunrise", th ...

(the Arab lands east of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

), particularly in countries of the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

. The political orientation of Arab nationalists before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was generally moderate. Their demands were of a reformist nature and generally limited to autonomy, a greater use of Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

in education and changes in peacetime conscription in the Ottoman Empire

Military conscription in the Ottoman Empire varied in the periods of:

* the Classical Army (1451–1606)

* the Reform Period (1826–1858)

* the Modern Army (1861–1922)

A complex set of rules applied, which involved:

* A poll-tax ...

to allow Arab conscripts local service in the Ottoman army.

The Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

began on 3 July 1908 and quickly spread throughout the empire. As a result, Sultan Abdul Hamid II was forced to announce the restoration of the 1876 constitution and the reconvening of the Ottoman parliament

The General Assembly ( tr, Meclis-i Umumî (French romanization: "Medjliss Oumoumi" ) or ''Genel Parlamento''; french: Assemblée Générale) was the first attempt at representative democracy by the imperial government of the Ottoman Empire. Als ...

. The period is known as the Second Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era ( ota, ایكنجی مشروطیت دورى; tr, İkinci Meşrutiyet Devri) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 dissolution of the ...

. In the 1908 elections, the Young Turks' Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP) managed to gain the upper hand against the Liberal Union, led by Sultanzade Sabahaddin

Prince Sabahaddin de Neuchâtel (born Sultanzade Mehmed Sabâhaddin Bey; 13 February 1879 – 30 June 1948) was an Ottoman sociologist and thinker. Because of his threat to the ruling House of Osman (the Ottoman dynasty), of which he was a ...

. The new parliament had 142 Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

, 60 Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, 25 Albanians, 23 Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, 12 Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

(including four Dashnaks

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

and two Hunchaks), five Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, four Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely unders ...

, three Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

and one Vlach

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easter ...

.

The CUP now gave more emphasis to centralisation and a modernisation. It preached a message that was a mixture of pan-Islamism, Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, tr, Osmanlıcılık) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the social cohesion needed to keep mille ...

, and pan-Turkism

Pan-Turkism is a political movement that emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals who lived in the Russian region of Kazan (Tatarstan), Caucasus (modern-day Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey), with its aim bei ...

, which was adjusted as the conditions warranted. At heart, the CUP were Turkish nationalists who wanted to see the Turks as the dominant group within the Ottoman Empire, which antagonised Arab leaders and prompted them to think in similarly nationalistic terms. Arab members of the parliament supported the countercoup of 1909, which aimed to dismantle the constitutional system and to restore the absolute monarchy of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The dethroned sultan attempted to restore the Ottoman Caliphate

The Caliphate of the Ottoman Empire ( ota, خلافت مقامى, hilâfet makamı, office of the caliphate) was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty to be the caliphs of Islam in the late medieval and the early modern era. ...

by putting an end to the secular policies of the Young Turks, but he was, in turn, driven away to exile in Selanik by the 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

in which the Young Turks defeated the countercoup, and he was eventually replaced by his brother Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd ( ota, محمد خامس, Meḥmed-i ḫâmis; tr, V. Mehmed or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) reigned as the 35th and penultimate Ottoman Sultan (). He was the son of Sultan Abdulmejid I. He succeeded his half-brother ...

.

In 1913, intellectuals and politicians from the Mashriq met in Paris at the First Arab Congress. They produced a set of demands for greater autonomy and equality within the Ottoman Empire, including for elementary and secondary education in Arab lands to be delivered in Arabic, for peacetime Arab conscripts to the Ottoman army to serve near their home region and for at least three Arab ministers in the Ottoman cabinet.

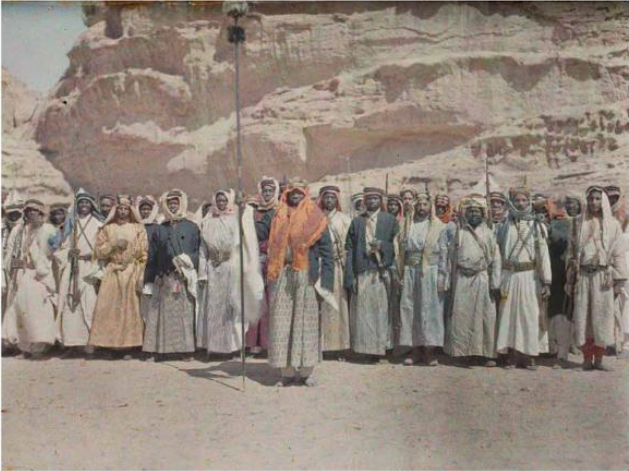

Forces

It is estimated that the Arab forces involved in the revolt numbered around 5000 soldiers.Murphy, p. 34. This number however probably applies to the Arab regulars who fought during the Sinai and Palestine campaign with Edmund Allenby'sEgyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning ...

, and not the irregular forces under the direction of T. E. Lawrenceand Faisal. On a few occasions, particularly during the final campaign into Syria, this number would grow significantly. Many Arabs joined the Revolt sporadically, often as a campaign was in progress or only when the fighting entered their home region. During the Battle of Aqaba

The Battle of Aqaba (6 July 1917) was fought for the Red Sea port of Aqaba (now in Jordan) during the Arab Revolt of World War I. The attacking forces, led by Sherif Nasir and Auda abu Tayi and advised by T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), ...

, for instance, while the initial Arab force numbered only a few hundred, over a thousand more from local tribes joined them for the final assault on Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, العقبة, al-ʿAqaba, al-ʿAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Govern ...

. Estimates of Faisal's effective forces vary, but through most of 1918 at least, they may have numbered as high as 30,000 men.

The Hashemite Army comprised two distinctive forces: tribal irregulars who waged a guerrilla war against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and the Sharifian Army, which was recruited from Ottoman Arab POWs and fought in conventional battles. Hashemite forces were initially poorly equipped, but later were to receive significant supplies of weapons, most notably rifles and machine guns from Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

.

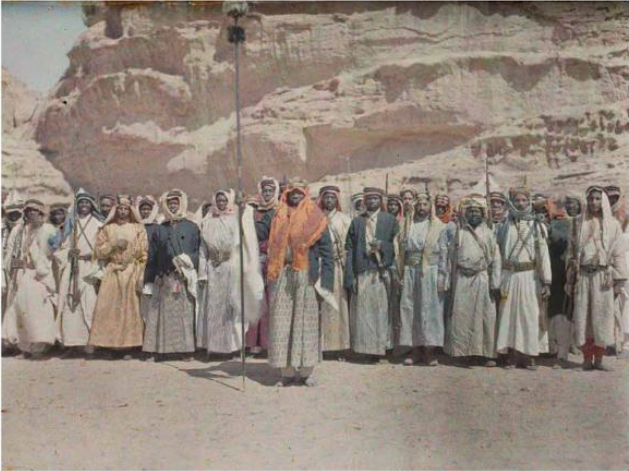

In the early days of the revolt, Faisal's forces were largely made up of Bedouins and other nomadic desert tribes, who were only loosely allied, loyal more to their respective tribes than the overall cause.Murphy, p. 21. The Bedouin would not fight unless paid in advance with gold coin, and by the end of 1916, the French had spent 1.25 million gold francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

in subsidizing the revolt. By September 1918, the British were spending £220,000/month to subsidize the revolt.

Faisal had hoped that he could convince Arab troops serving in the Ottoman Army to mutiny and join his cause, but the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

sent most of its Arab troops to the Western front-lines of the war, and thus only a handful of deserters actually joined the Arab forces until later in the campaign.Murphy, p. 24.

Ottoman troops in the Hejaz numbered 20,000 men by 1917. At the outbreak of the revolt in June 1916, the VII Corps of the Fourth Army was stationed in the Hejaz to be joined by the 58th Infantry Division commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Ali Necib Pasha, the 1st ''Kuvvie- Mürettebe'' (Provisional Force) led by General Mehmed Cemal Pasha, which had the responsibility of safeguarding the Hejaz railway and the Hejaz Expeditionary Force ( tr, Hicaz Kuvve-i Seferiyesi), which was under the command of General Fakhri Pasha

Ömer Fahrettin Türkkan, commonly known as Fahreddin Pasha and nicknamed the Defender of Medina, was a Turkish career officer, who was the commander of the Ottoman Army and governor of Medina from 1916 to 1919. He was nicknamed "''The Lion of ...

. In face of increasing attacks on the Hejaz railway, the 2nd ''Kuvve i Mürettebe'' was created by 1917. The Ottoman force included a number of Arab units who stayed loyal to the Sultan-Caliph and fought well against the Allies.

The Ottoman troops enjoyed an advantage over the Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

troops at first in that they were well supplied with modern German weapons. In addition, the Ottoman forces had the support of both the Ottoman Aviation Squadrons, air squadrons from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and the Ottoman Gendarmerie

The Ottoman Gendarmerie ( tr, Jandarma), also known as ''zaptı'', was a security and public order organization (a precursor to law enforcement) in the 19th-century Ottoman Empire. The first official gendarmerie organization was founded in 1869.

...

or ''zaptı''.Murphy, p. 23. Moreover, the Ottomans relied upon the support of Emir Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Rashid

Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Rashid ( ar, سعود بن عبدالعزيز الرشيد, Suʿūd ibn ʿAbdulʿazīz Āl Rašid; 1898 – 1920) was the tenth Emir of Jabal Shammar between 1908 and 1920.

Biography

It is likely that he was born in 1898 ...

of the Emirate of Jabal Shammar

The Emirate of Jabal Shammar ( ar, إِمَارَة جَبَل شَمَّر), also known as the Emirate of Haʾil () or the Rashidi Emirate (), was a state in the northern part of the Arabian Peninsula, including Najd, existing from the mid-nin ...

, whose tribesmen dominated what is now northern Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

and tied down both the Hashemites and Saʻudi forces with the threat of their raiding attacks.

The great weakness of the Ottoman forces was they were at the end of a long and tenuous supply line in the form of the Hejaz railway, and because of their logistical weaknesses, were often forced to fight on the defensive. Ottoman offensives against the Hashemite forces more often faltered due to supply problems than to the actions of the enemy.

The main contribution of the Arab Revolt to the war was to pin down tens of thousands of Ottoman troops who otherwise might have been used to attack the Suez Canal and conquering Damascus, allowing the British to undertake offensive operations with a lower risk of counter-attack. This was indeed the British justification for supporting the revolt, a textbook example of asymmetric warfare

Asymmetric warfare (or asymmetric engagement) is the term given to describe a type of war between belligerents whose relative military power, strategy or tactics differ significantly. This is typically a war between a standing, professional ar ...

that has been studied time and again by military leaders and historians alike.

History

Revolt

The Ottoman Empire took part in theMiddle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I saw action between 29 October 1914 and 30 October 1918. The combatants were, on one side, the Ottoman Empire (including the majority of Kurdish tribes, a relative majority of Arabs, and Caucasian ''T ...

, under the terms of the Ottoman–German Alliance. Many Arab nationalist figures in Damascus and Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

were arrested, then tortured. The flag of the resistance was designed by Sir Mark Sykes, in an effort to create a feeling of "Arab-ness" in order to fuel the revolt.

Prelude (November 1914 – October 1916)

When Herbert Kitchener was Consul-General in

When Herbert Kitchener was Consul-General in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, contacts between Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

and Kitchener had eventually culminated in a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

of 1 November 1914 from Kitchener (recently appointed as Secretary of War) to Hussein wherein Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

would, in exchange for support from the Arabs of Hejaz, "guarantee the independence, rights and privileges of the Sharifate against all foreign external aggression, in particular that of the Ottomans" The Sharif

Sharīf ( ar, شريف, 'noble', 'highborn'), also spelled shareef or sherif, feminine sharīfa (), plural ashrāf (), shurafāʾ (), or (in the Maghreb) shurfāʾ, is a title used to designate a person descended, or claiming to be descended, f ...

indicated that he could not break with the Ottomans immediately, and it did not happen till the following year. From July 14, 1915, to March 10, 1916, a total of ten letters, five from each side, were exchanged between Sir Henry McMahon and Sherif Hussein. Hussein's letter of 18 February 1916 appealed to McMahon for £50,000 in gold plus weapons, ammunition, and food. Faisal claimed that he was awaiting the arrival of 'not less than 100,000 people' for the planned revolt. McMahon's reply of 10 March 1916 confirmed British agreement to the requests and concluded the correspondence. Hussein, who until then had officially been on the Ottoman side, was now convinced that his assistance to the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

would be rewarded by an Arab empire encompassing the entire span between Egypt and Qajar Iran

Qajar Iran (), also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, '. Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran ( fa, دولت علیّه ایران ') and also known then as the Guarded Domains of Iran ( fa, ممالک م ...

, with the exception of imperial possessions and interests in Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

, Aden, and the Syrian coast. He decided to join the Allied camp immediately, because of rumours that he would soon be deposed as Sharif of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

by the Ottoman government in favor of Sharif Ali Haidar, leader of the rival Zaʻid family. The much-publicized executions of the Arab nationalist leaders in Damascus led Hussein to fear for his life if he were deposed in favour of Ali Haidar.

Hussein had about 50,000 men under arms, but fewer than 10,000 had rifles.Parnell, p. 75 On June 5, 1916, two of Hussein's sons, the emirs ʻAli and Faisal, began the revolt by attacking the Ottoman garrison in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, but were defeated by an aggressive Turkish defence led by Fakhri Pasha. The revolt proper began on June 10, 1916, when Hussein ordered his supporters to attack the Ottoman garrison in Mecca. In the Battle of Mecca, there ensued over a month of bloody street fighting between the out-numbered, but far better armed Ottoman troops and Hussein's tribesmen. Hashemite forces in Mecca were joined by Egyptian troops sent by the British, who provided much needed artillery support, and finally took Mecca on July 9, 1916.

Indiscriminate Ottoman artillery fire, which did much damage to Mecca, turned out to be a potent propaganda weapon for the Hashemites, who portrayed the Ottomans as desecrating Islam's most holy city. Also on June 10, another of Hussein's sons, the Emir Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

, attacked Ta'if

Taif ( ar, , translit=aṭ-Ṭāʾif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

, which after an initial repulse settled down into a siege. With the Egyptian artillery support, Abdullah took Ta'if on September 22, 1916.

French and British naval forces had cleared the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

of Ottoman gunboats early in the war.Parnell, p. 76 The port of Jeddah was attacked by 3500 Arabs on 10 June 1916 with the assistance of bombardment by British warships and seaplanes. The seaplane carrier provided crucial air support to the Hashemite forces.Murphy, p. 35. The Ottoman garrison surrendered on 16 June. By the end of September 1916, the Sharifian Army had taken the coastal cities of Rabigh, Yanbu

Yanbu ( ar, ينبع, lit=Spring, translit=Yanbu'), also known simply as Yambu or Yenbo, is a city in the Al Madinah Province of western Saudi Arabia. It is approximately 300 kilometers northwest of Jeddah (at ). The population is 222,360 (2 ...

, al Qunfudhah, and 6,000 Ottoman prisoners with the assistance of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

.

The capture of the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

ports allowed the British to send over a force of 700 Ottoman Arab POWs (who primarily came from what is now Iraq) who had decided to join the revolt led by Nuri al-Saʻid and a number of Muslim troops from French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. I ...

. Fifteen thousand well-armed Ottoman troops remained in the Hejaz. However, a direct attack on Medina in October resulted in a bloody repulse of the Arab forces.

Arrival of T. E. Lawrence (October 1916 – January 1917)

In June 1916, the British sent out a number of officials to assist the revolt in the Hejaz, most notably Colonel Cyril Wilson, Colonel Pierce C. Joyce, and Lt-Colonel Stewart Francis Newcombe.Murphy, p. 17. Herbert Garland was also involved. In addition, a French military mission commanded by Colonel

In June 1916, the British sent out a number of officials to assist the revolt in the Hejaz, most notably Colonel Cyril Wilson, Colonel Pierce C. Joyce, and Lt-Colonel Stewart Francis Newcombe.Murphy, p. 17. Herbert Garland was also involved. In addition, a French military mission commanded by Colonel Édouard Brémond Édouard is both a French given name and a surname, equivalent to Edward in English. Notable people with the name include:

* Édouard Balladur (born 1929), French politician

* Édouard Boubat (1923–1999), French photographer

* Édouard Colonne (1 ...

was sent out. The French enjoyed an advantage over the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

in that they included a number of Muslim officers such as Captain Muhammand Ould Ali Raho, Claude Prost, and Laurent Depui (the latter two converted to Islam during their time in Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

). Captain Rosario Pisani of the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Force ...

, though not a Muslim, also played a notable role in the revolt as an engineering and artillery officer with the Arab Northern Army.

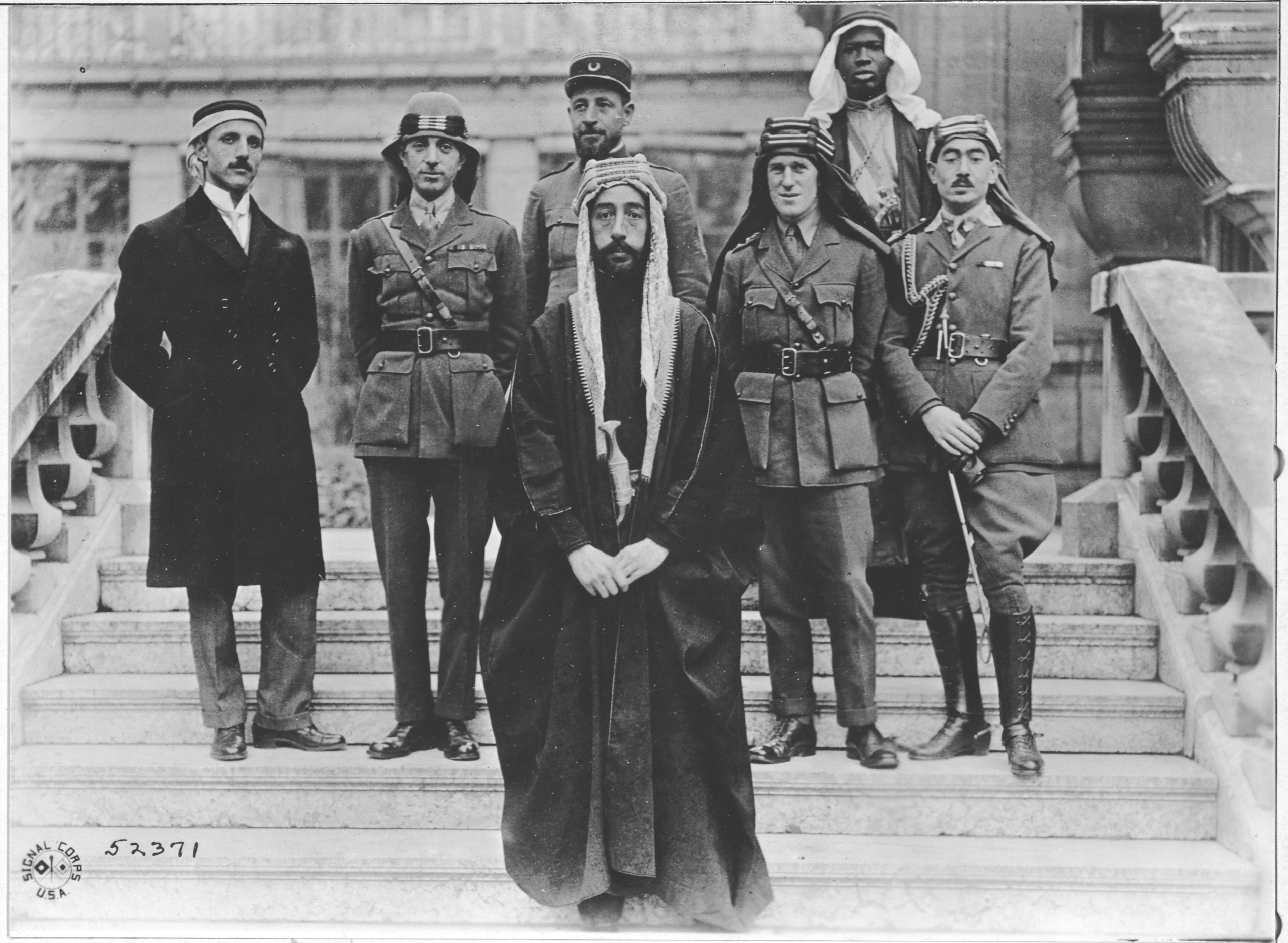

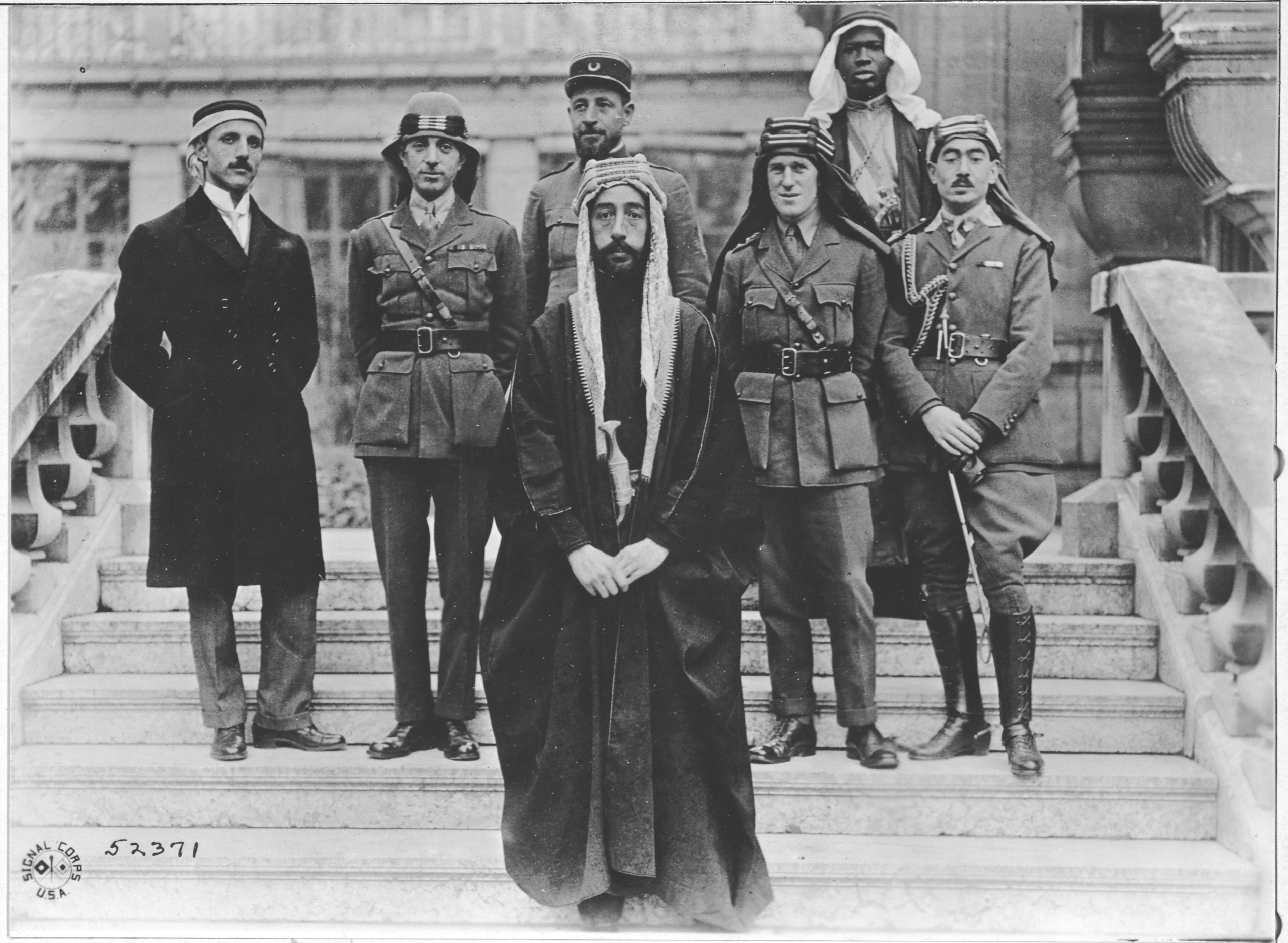

The British government in Egypt sent a young officer, Captain T. E. Lawrence, to work with the Hashemite forces in the Hejaz in October 1916. The British historian David Murphy wrote that though Lawrence was just one out of many British and French officers serving in Arabia, historians often write as though it was Lawrence alone who represented the Allied cause in Arabia.

David Hogarth credited Gertrude Bell

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell, CBE (14 July 1868 – 12 July 1926) was an English writer, traveller, political officer, administrator, and archaeologist. She spent much of her life exploring and mapping the Middle East, and became highl ...

for much of the success of the Arab Revolt. She had travelled extensively in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

since 1888, after graduating from Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

with a First in Modern History. Bell had met Sheikh Harb of the Howeitat

The Howeitat or Huwaitat ( ar, الحويطات ''al-Ḥuwayṭāt'', Northwest Arabian dialect: ''ál-Ḥwēṭāt'') are a large Judhami tribe, that inhabits areas of present-day southern Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula and Sharqia governate in Eg ...

in January 1914 and thus was able to provide a "mass of information" which was crucial to the success of Lawrence's occupation of Aqaba covering the "tribal elements ranging between the Hejaz Railway and the Nefud

An Nafud or Al-Nefud or The Nefud ( ar, صحراء النفود, ṣahrā' an-Nafūd) is a desert in the northern part of the Arabian Peninsula at , occupying a great oval depression. It is long and wide, with an area of .

The Nafud is an erg, ...

, particularly about the Howeitat group." It was this information, Hogarth emphasized, which "Lawrence, relying on her reports, made signal use of in the Arab campaigns of 1917 and 1918."

Lawrence obtained assistance from the

Lawrence obtained assistance from the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

to turn back an Ottoman attack on Yenbu in December 1916.Parnell, p. 78 Lawrence's major contribution to the revolt was convincing the Arab leaders ( Faisal and Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

) to co-ordinate their actions in support of British strategy. Lawrence developed a close relationship with Faisal, whose Arab Northern Army was to become the main beneficiary of British aid.Murphy, p. 36. By contrast, Lawrence's relations with Abdullah were not good, so Abdullah's Arab Eastern Army received considerably less in way of British aid. Lawrence persuaded the Arabs not to drive the Ottomans out of Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

; instead, the Arabs attacked the Hejaz railway on many occasions. This tied up more Ottoman troops, who were forced to protect the railway and repair the constant damage.

On December 1, 1916, Fakhri Pasha began an offensive with three brigades out of Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

with the aim of taking the port of Yanbu

Yanbu ( ar, ينبع, lit=Spring, translit=Yanbu'), also known simply as Yambu or Yenbo, is a city in the Al Madinah Province of western Saudi Arabia. It is approximately 300 kilometers northwest of Jeddah (at ). The population is 222,360 (2 ...

. At first, Fakhri's troops defeated the Hashemite forces in several engagements, and seemed set to take Yanbu.Murphy, p. 37. It was fire and air support from the five ships of the Royal Navy Red Sea Patrol that defeated the Ottoman attempts to take Yanbu with heavy losses on December 11–12, 1916. Fakhri then turned his forces south to take Rabegh, but owing to the guerrilla attacks on his flanks and supply lines, air attacks from the newly established Royal Flying Corps base at Yanbu, and the over-extension of his supply lines, he was forced to turn back on January 18, 1917, to Medina.Murphy, p. 38.

The coastal city of Wejh was to be the base for attacks on the Hejaz railway. On 3 January 1917, Faisal began an advance northward along the Red Sea coast with 5,100 camel riders, 5,300 men on foot, four Krupp mountain guns, ten machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) ar ...

s, and 380 baggage camels. The Royal Navy resupplied Faisal from the sea during his march on Wejh.Parnell, p. 79 While the 800-man Ottoman garrison prepared for an attack from the south, a landing party of 400 Arabs and 200 Royal Navy bluejackets attacked Wejh from the north on 23 January 1917. Wejh surrendered within 36 hours, and the Ottomans abandoned their advance toward Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

in favor of a defensive position in Medina with small detachments scattered along the Hejaz railway.Parnell, p. 80 The Arab force had increased to about 70,000 men armed with 28,000 rifles and deployed in three main groups. Ali's force threatened Medina, Abdullah operated from Wadi Ais harassing Ottoman communications and capturing their supplies, and Faisal based his force at Wejh. Camel-mounted Arab raiding parties had an effective radius of 1,000 miles (1,600 km) carrying their own food and taking water from a system of wells approximately 100 miles (160 km) apart.Parnell, p. 81 In late 1916, the Allies started the formation of the Regular Arab Army (also known as the Sharifian Army) raised from Ottoman Arab POWs. The soldiers of the Regular Army wore British-style uniforms with the ''keffiyahs'' and, unlike the tribal guerrillas, fought full-time and in conventional battles. Some of the more notable former Ottoman officers to fight in the Revolt were Nuri as-Said, Jafar al-Askari

Ja'far Pasha al-Askari ( ar, جعفر العسكري; 15 September 1885 – 29 October 1936) served twice as prime minister of Iraq: from 22 November 1923 to 3 August 1924; and from 21 November 1926 to 31 December 1927.

Al-Askari served in th ...

and 'Aziz 'Ali al-Misri.

Northward expeditions (January 1917 – November 1917)

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, Captain Muhammad Ould Ali Raho of the French Military Mission carried out his first railway demolition attack in February 1917.Murphy, pp. 43–44. Captain Raho was to emerge as one of the leading destroyers of the Hejaz railway. In March 1917, Lawrence led his first attack on the Hejaz railway.Murphy, p. 44. Typical of such attacks were the one commanded out by Newcombe and Joyce who on the night of July 6/7, 1917 when they had planted over 500 charges on the Hejaz railway, which all went off at about 2 am. In a raid in August 1917, Captain Raho led a force of Bedouin in destroying 5 kilometers of the Hejaz railway and four bridges.

In March 1917, an Ottoman force joined by tribesmen from Jabal Shammar

The Emirate of Jabal Shammar ( ar, إِمَارَة جَبَل شَمَّر), also known as the Emirate of Haʾil () or the Rashidi Emirate (), was a state in the northern part of the Arabian Peninsula, including Najd, existing from the mid-nin ...

led by Ibn Rashid

The Rasheed dynasty, also called Al Rasheed or the House of Rasheed ( ar, آل رشيد ; ), was a historic Arabian House or dynasty that existed in the Arabian Peninsula between 1836 and 1921. Its members were rulers of the Emirate of Ha'il a ...

carried out a sweep of the Hejaz that did much damage to the Hashemite forces. However, the Ottoman failure to take Yanbu

Yanbu ( ar, ينبع, lit=Spring, translit=Yanbu'), also known simply as Yambu or Yenbo, is a city in the Al Madinah Province of western Saudi Arabia. It is approximately 300 kilometers northwest of Jeddah (at ). The population is 222,360 (2 ...

in December 1916 led to the increased strengthening of the Hashemite forces, and led to the Ottoman forces to assume the defensive. Lawrence was later to claim that the failure of the offensive against Yanbu was the turning point that ensured the ultimate defeat of the Ottomans in the Hejaz.

In 1917, Lawrence arranged a joint action with the Arab irregulars and forces under Auda Abu Tayi (until then in the employ of the Ottomans) against the port city of Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, العقبة, al-ʿAqaba, al-ʿAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Govern ...

. This is now known as the Battle of Aqaba

The Battle of Aqaba (6 July 1917) was fought for the Red Sea port of Aqaba (now in Jordan) during the Arab Revolt of World War I. The attacking forces, led by Sherif Nasir and Auda abu Tayi and advised by T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), ...

. Aqaba was the only remaining Ottoman port on the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

and threatened the right flank of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

's Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning ...

defending Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and preparing to advance into Sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

Maan of the Syria Vilayet. Capture of Aqaba would aid transfer of British supplies to the Arab revolt.Parnell, p. 82 Lawrence and Auda left Wedj on 9 May 1917 with a party of 40 men to recruit a mobile force from the Howeitat

The Howeitat or Huwaitat ( ar, الحويطات ''al-Ḥuwayṭāt'', Northwest Arabian dialect: ''ál-Ḥwēṭāt'') are a large Judhami tribe, that inhabits areas of present-day southern Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula and Sharqia governate in Eg ...

, a tribe located in the area. On 6 July, after an overland attack, Aqaba fell to those Arab forces with only a handful of casualties. Lawrence then rode 150 miles to Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

to arrange Royal Navy delivery of food and supplies for the 2,500 Arabs and 700 Ottoman prisoners in Aqaba; soon the city was co-occupied by a large Anglo-French flotilla (including warships and sea planes), which helped the Arabs secure their hold on Aqaba. Even as the Hashemite armies advanced, they still encountered sometimes fierce opposition from local residents. In July 1917, residents of the town of Karak fought against the Hashemite forces and turned them back. Later in the year British intelligence reports suggested that most of the tribes in the region east of the Jordan River were "firmly in the Ottoman camp." The tribes feared repressions and losing the money they had received from the Ottomans for their loyalty. Later in the year, the Hashemite warriors made a series of small raids on Ottoman positions in support of British General Allenby's winter attack on the Gaza– Bersheeba defensive line, which led to the Battle of Beersheba.Parnell, p. 83 Typical of such raids was one led by Lawrence in September 1917 that saw Lawrence destroy a Turkish rail convoy by blowing up the bridge it was crossing at Mudawwara and then ambushing the Turkish repair party. In November 1917, as aid to Allenby's offensive, Lawrence launched a deep-raiding party into the Yarmouk River

The Yarmuk River ( ar, نهر اليرموك, translit=Nahr al-Yarmūk, ; Greek: Ἱερομύκης, ; la, Hieromyces or ''Heromicas''; sometimes spelled Yarmouk), is the largest tributary of the Jordan River. It runs in Jordan, Syria and Israel ...

valley, which failed to destroy the railway bridge at Tel ash-Shehab, but which succeeded in ambushing and destroying the train of General Mehmed Cemal Pasha, the commander of the Ottoman VII Corps. Allenby's victories led directly to the British capture of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

just before Christmas 1917.

Increased Allied assistance and the end of fighting (November 1917– October 1918)

By the time of

By the time of Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, العقبة, al-ʿAqaba, al-ʿAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Govern ...

's capture, many other officers joined Faisal's campaign. A large number of British officers and advisors, led by Lt. Col.s Stewart F. Newcombe and Cyril E. Wilson, arrived to provide the Arabs rifles, explosives, mortars, and machine guns.Murphy, p. 59. Artillery was only sporadically supplied due to a general shortage, though Faisal would have several batteries of mountain guns under French Captain Pisani and his Algerians for the Megiddo Campaign. Egyptian and Indian troops also served with the Revolt, primarily as machine gunners and specialist troops, a number of armoured cars

Armored (or armoured) car or vehicle may refer to:

Wheeled armored vehicles

* Armoured fighting vehicle, any armed combat vehicle protected by armor

** Armored car (military), a military wheeled armored vehicle

* Armored car (valuables), an arm ...

were allocated for use. The Royal Flying Corps often supported the Arab operations, and the Imperial Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East.

From a small beginning the unit eventually grew to a brigad ...

served with the Arabs for a time. The French military mission of 1,100 officers under Brémond established good relations with Hussein and especially with his sons, the Emirs Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

and Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

, and for this reason, most of the French effort went into assisting the Arab Southern Army commanded by the Emir Ali that was laying siege to Medina and the Eastern Army commanded by Abdullah that had the responsibility of protecting Ali's eastern flank from Ibn Rashid. Medina was never taken by the Hashemite forces, and the Ottoman commander, Fakhri Pasha, only surrendered Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

when ordered to by the Turkish government on January 9, 1919.Murphy, p. 81. The total number of Ottoman troops bottled up in Medina by the time of the surrender were 456 officers and 9364 soldiers.

Under the direction of Lawrence, Wilson, and other officers, the Arabs launched a highly successful campaign against the Hejaz railway, capturing military supplies, destroying trains and tracks, and tying down thousands of Ottoman troops. Though the attacks were mixed in success, they achieved their primary goal of tying down Ottoman troops and cutting off Medina. In January 1918, in one of the largest set-piece battles of the Revolt, Arab forces (including Lawrence) defeated a large Ottoman force at the Battle of Tafilah, inflicting over 1,000 Ottoman casualties for the loss of a mere forty men.

In March 1918 the Arab Northern Army consisted of

:Arab Regular Army commanded by Ja'far Pasha el Askeri

::brigade of infantry

::one battalion Camel Corps

::one battalion mule-mounted infantry

::about eight guns

:British Section commanded by Lieutenant Colonel P. C. Joyce

::Hejaz Armoured Car Battery of Rolls Royce light armoured cars with machine guns and two 10-pdr guns on Talbot lorries

::one Flight of aircraft

::one Company Egyptian Camel Corps

:: Egyptian Camel Transport Corps

::Egyptian Labour Corps

::Wireless Station at 'Aqaba

:French Detachment commanded by Captain Pisani

::two mountain guns

::four machine guns and 10 automatic rifles

In April 1918, Jafar al-Askari

Ja'far Pasha al-Askari ( ar, جعفر العسكري; 15 September 1885 – 29 October 1936) served twice as prime minister of Iraq: from 22 November 1923 to 3 August 1924; and from 21 November 1926 to 31 December 1927.

Al-Askari served in th ...

and Nuri as-Said led the Arab Regular Army in a frontal attack on the well-defended Ottoman railway station at Ma'an

Ma'an ( ar, مَعان, Maʿān) is a city in southern Jordan, southwest of the capital Amman. It serves as the capital of the Ma'an Governorate. Its population was approximately 41,055 in 2015. Civilizations with the name of Ma'an have existe ...

, which after some initial successes was fought off with heavy losses to both sides. However, the Sharifian Army succeeded in cutting off and thus neutralizing the Ottoman position at Ma'an, who held out until late September 1918.Murphy, p. 73. The British refused several requests from al-Askari to use mustard gas on the Ottoman garrison at Ma'an.

In the spring of 1918, Operation Hedgehog, a concerted attempt to sever and destroy the Hejaz railway, was launched. In May 1918, Hedgehog led to the destruction of 25 bridges of the Hejaz railway. On 11 May Arab regulars captured Jerdun and 140 prisoners. Five weeks later, on 24 July Nos. 5 and 7 Companies of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East.

From a small beginning the unit eventually grew to a bri ...

commanded by Major R. V. Buxton, marched from the Suez Canal to arrive at Aqaba on 30 July, to attack the Mudawwara Station.Falls, p. 408 A particularly notable attack of Hedgehog was the storming on August 8, 1918, by the Imperial Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East.

From a small beginning the unit eventually grew to a brigad ...

, closely supported by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

, of the well-defended Hejaz railway station at Mudawwara. They captured 120 prisoners and two guns, suffering 17 casualties in the operation. Buxton's two companies of Imperial Camel Corps Brigade continued on towards Amman, where they hoped to destroy the main bridge. However from the city they were attacked by aircraft, forcing them to withdraw eventually back to Beersheba

Beersheba or Beer Sheva, officially Be'er-Sheva ( he, בְּאֵר שֶׁבַע, ''Bəʾēr Ševaʿ'', ; ar, بئر السبع, Biʾr as-Sabʿ, Well of the Oath or Well of the Seven), is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. ...

where they arrived on 6 September; a march of in 44 days. For the final Allied offensive intended to knock the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

out of the war, Allenby asked that Emir Faisal and his Arab Northern Army launch a series of attacks on the main Turkish forces from the east, which was intended to both tie down Ottoman troops and force Turkish commanders to worry about their security of their flanks in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

. Supporting the Emir Faisal's army of about 450 men from the Arab Regular Army were tribal contingents from the Rwalla, Bani Sakhr, Agyal, and Howeitat tribes. In addition, Faisal had a group of Gurkha

The Gurkhas or Gorkhas (), with endonym Gorkhali ), are soldiers native to the Indian subcontinent, Indian Subcontinent, chiefly residing within Nepal and some parts of Northeast India.

The Gurkha units are composed of Nepalis and Indian Go ...

troops, several British armored car squadrons, the Egyptian Camel Corps, a group of Algerian artillery men commanded by Captain Pisani and air support from the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

to assist him.

In 1918, the Arab cavalry gained in strength (as it seemed victory was at hand) and they were able to provide Allenby's army with intelligence on Ottoman army positions. They also harassed Ottoman supply columns, attacked small garrisons, and destroyed railway tracks. A major victory occurred on 27 September when an entire brigade of Ottoman, Austrian and German troops, retreating from Mezerib, was virtually wiped out in a battle with Arab forces near the village of Tafas (which the Turks had plundered during their retreat).Murphy, pp. 76–77. This led to the so-called Tafas massacre, in which Lawrence claimed in a letter to his brother to have issued a "no-prisoners" order, maintaining after the war that massacre was in retaliation for the earlier Ottoman massacre of the village of Tafas, and that he had at least 250 German and Austrian POWs together with an uncounted number of Turks lined up to be summarily shot. Lawrence later wrote in ''

In 1918, the Arab cavalry gained in strength (as it seemed victory was at hand) and they were able to provide Allenby's army with intelligence on Ottoman army positions. They also harassed Ottoman supply columns, attacked small garrisons, and destroyed railway tracks. A major victory occurred on 27 September when an entire brigade of Ottoman, Austrian and German troops, retreating from Mezerib, was virtually wiped out in a battle with Arab forces near the village of Tafas (which the Turks had plundered during their retreat).Murphy, pp. 76–77. This led to the so-called Tafas massacre, in which Lawrence claimed in a letter to his brother to have issued a "no-prisoners" order, maintaining after the war that massacre was in retaliation for the earlier Ottoman massacre of the village of Tafas, and that he had at least 250 German and Austrian POWs together with an uncounted number of Turks lined up to be summarily shot. Lawrence later wrote in ''The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

''Seven Pillars of Wisdom'' is the autobiographical account of the experiences of British Army Colonel T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), of serving as a military advisor to Bedouin forces during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire o ...

'' that "In a madness born of the horror of Tafas we killed and killed, even blowing in the heads of the fallen and of the animals; as though their death and running blood could slake our agony". In part due to these attacks, Allenby's last offensive, the Battle of Megiddo, was a stunning success. By late September and October 1918, an increasingly demoralized Ottoman Army began to retreat and surrender whenever possible to British troops. "Sherifial irregulars" accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel T. E. Lawrence captured Deraa on 27 September 1918. The Ottoman army was routed in less than 10 days of battle. Allenby praised Faisal for his role in the victory: "I send your Highness my greetings and my most cordial congratulations upon the great achievement of your gallant troops ... Thanks to our combined efforts, the Ottoman army is everywhere in full retreat".

The first Arab Revolt forces to reach Damascus were Sharif Naser's Hashemite camel cavalry and the cavalry of the Ruwallah tribe, led by Nuri Sha'lan, on 30 September 1918. The bulk of these troops remained outside of the city with the intention of awaiting the arrival of Sharif Faisal. However, a small contingent from the group was sent within the walls of the city, where they found the Arab Revolt flag already raised by surviving Arab nationalists among the citizenry. Later that day Australian Light Horse troops marched into Damascus. Auda Abu Ta'yi, T. E. Lawrence and Arab troops rode into Damascus the next day, 1 October. At the end of the war, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning ...

had seized Palestine, Transjordan, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

, large parts of the Arabian peninsula and southern Syria

Southern Syria (سوريا الجنوبية, ''Suriyya al-Janubiyya'') is the southern part of the Syria region, roughly corresponding to the Southern Levant. Typically it refers chronologically and geographically to the southern part of Ottom ...

. Medina, cut off from the rest of the Ottoman Empire, would not surrender until January 1919.

Aftermath

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

agreed in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I in which the Government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif ...

that it would support Arab independence if they revolted against the Ottomans. Both sides had different interpretations of this agreement.

However, the United Kingdom and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

reneged on the original deal and divided up the area under the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement in ways that the Arabs felt were unfavourable to them. Further confusing the issue was the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised support for a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

"national home" in Palestine. For a brief period, the Hejaz region of western Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

became a self-declared state, without being universally recognised as such, under Hussein's control. It was eventually conquered by Ibn Saud with British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

aid in 1925, as part of his military and sociopolitical campaign for the unification of Saudi Arabia

The Unification of Saudi Arabia was a military and political campaign in which the various tribes, sheikhdoms, city-states, emirates, and kingdoms of most of the Arabian Peninsula were conquered by the House of Saud, or ''Al Saud''. Unifica ...

.

The Arab Revolt is seen by historians as the first organized movement of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language a ...

. It brought together different Arab groups for the first time with the common goal to fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Much of the history of Arab independence stemmed from the revolt beginning with the kingdom that had been founded by Hussein.

After the war, the Arab Revolt had implications. Groups of people were put into classes that were based on whether they had fought in the revolt and their rank. In Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, a group of Sharifian officers from the Arab Revolt formed a political party that they headed. The Hashemites in Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

remain influenced by the actions of the revolt's Arab leaders.

Underlying causes

Hussein

According toEfraim Karsh

Efraim Karsh ( he, אפרים קארש; born 1953) is an Israeli–British historian who is the founding director and emeritus professor of Middle East and Mediterranean Studies at King's College London. Since 2013, he has served as professor of p ...

of Bar-Ilan University

Bar-Ilan University (BIU, he, אוניברסיטת בר-אילן, ''Universitat Bar-Ilan'') is a public research university in the Tel Aviv District city of Ramat Gan, Israel. Established in 1955, Bar Ilan is Israel's second-largest academi ...

, Sharif Hussein of Mecca was "a man with grandiose ambitions" who had first started to fall out with his masters in Istanbul when the dictatorship, a triumvirate known as the Three Pashas

The Three Pashas also known as the Young Turk triumvirate or CUP triumvirate consisted of Mehmed Talaat Pasha (1874–1921), the Grand Vizier (prime minister) and Minister of the Interior; Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Minister of War ...

(General Enver Pasha, Talaat Pasha, and Cemal Pasha), which represented the radical Turkish nationalist

Turkish nationalism ( tr, Türk milliyetçiliği) is a political ideology that promotes and glorifies the Turkish people, as either a national, ethnic, or linguistic group. The term "ultranationalism" is often used to describe Turkish nationali ...

wing of the CUP, seized power in a coup d'état in January 1913 and began to pursue a policy of Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

, which gradually angered non-Turkish subjects. Hussein started to embrace the language of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language a ...

only after the Young Turks revolt against the Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II in July 1908. The fighting force of the revolt was mostly combined from Ottoman defectors and Arabian tribes loyal to the Sharif.

Religious justification

Though the Sharifian revolt has tended to be regarded as a revolt rooted in a secular Arab nationalist sentiment, the Sharif did not present it in those terms. Rather, he accused the Young Turks of violating the sacred tenets of Islam by pursuing the policy ofTurkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

and discriminating against its non-Turkish population and called Arab Muslims to sacred rebellion against the Ottoman government. The Turks answered by accusing the rebelling tribes of betraying the Muslim Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

during a campaign against imperialist powers which were trying to divide and govern the Muslim lands. The Turks said the Revolting Arabs gained nothing after the revolt and rather the Middle East was carved up by the British And French

Ethnic tensions

While the revolt failed to garner significant support from within the Ottoman Empire's soon-to-be Iraq provinces, it did find huge support from Arab populated Levantine provinces. This earlyArab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language a ...

came about when the majority of the Arabs living in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

were loyal primarily to their own families, clans, and tribes despite efforts of the Turkish ruling class, who pursued a policy of Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

through the Tanzimat reforms and hoped to create a feeling of "Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, tr, Osmanlıcılık) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the social cohesion needed to keep mille ...

" among the different ethnicities under the Ottoman domain. Liberal reforms brought about by the Tanzimat also transformed the Ottoman Caliphate

The Caliphate of the Ottoman Empire ( ota, خلافت مقامى, hilâfet makamı, office of the caliphate) was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty to be the caliphs of Islam in the late medieval and the early modern era. ...

into a secular empire, which weakened the Islamic concept of ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

that tied the different races together. The arrival of Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

to power and the creation of a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

in 1913 which mandated Turkish nationalism

Turkish nationalism ( tr, Türk milliyetçiliği) is a political ideology that promotes and glorifies the Turkish people, as either a national, ethnic, or linguistic group. The term " ultranationalism" is often used to describe Turkish nationa ...

as a state ideology worsened the relationship between the Ottoman state and its non-Turkish subjects.

See also

* Campaigns of the Arab Revolt *Flag of the Arab Revolt

The flag of the Arab Revolt, also known as the flag of Hejaz, was a flag used by the Arab nationalists during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, and as the first flag of the Kingdom of Hejaz.

History

It has been sug ...

* History of Saudi Arabia

The history of Saudi Arabia as a nation state began with the emergence of the Al Saud dynasty in central Arabia in 1727 and the subsequent establishment of the Emirate of Diriyah. Pre-Islamic Arabia, the territory that constitutes modern Saudi ...

* South Arabia during World War I

The campaign in South Arabia during World War I was a minor struggle for control of the port city of Aden, an important way station for ships on their way from Asia to the Suez Canal. The British Empire declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 5 Nov ...

Notes

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

*Cleveland, William L. and Martin Bunton. (2016) ''A History of the Modern Middle East.'' 6th ed. Westview Press. *Falls, Cyril (1930) ''Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence; Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War'' Vol. 2. London: H. M. Stationary *Erickson, Edward. ''Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood. . * *Murphy, David (2008) ''The Arab Revolt 1916–18 Lawrence sets Arabia Ablaze''. Osprey: London. . *Parnell, Charles L. (August 1979) CDR USN "Lawrence of Arabia's Debt to Seapower" ''United States Naval Institute Proceedings''.Further reading

* Anderson, Scott (2014). ''Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East''. Atlantic Books. *Fromkin, David

David Henry Fromkin (August 27, 1932 June 11, 2017) was an American historian, best known for his interpretive account of the Middle East, ''A Peace to End All Peace'' (1989), in which he recounts the role European powers played between 1914 an ...

(1989). ''A Peace to End All Peace

''A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East'' (also subtitled ''Creating the Modern Middle East, 1914–1922'') is a 1989 history book written by Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction fina ...

''. Avon Books.

* Korda, Michael, ''Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia''. .

* Lawrence, T. E. (1935). ''Seven Pillars of Wisdom

''Seven Pillars of Wisdom'' is the autobiographical account of the experiences of British Army Colonel T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), of serving as a military advisor to Bedouin forces during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire ...

''. Doubleday, Doran, and Co.

* Oschenwald, William. 'Ironic Origins: Arab Nationalism in the Hijaz, 1882–1914' in ''The Origins of Arab Nationalism'' (1991), ed. Rashid Khalidi, pp. 189–203. Columbia University Press.