Anti-Stalinism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The anti-Stalinist left is an umbrella term for various kinds of left-wing political movements that opposed

Because of her early criticisms toward the Bolsheviks, her legacy was vilified by Stalin once he rose to power.Trotsky, Leon (June 1932). "Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!". ''

Because of her early criticisms toward the Bolsheviks, her legacy was vilified by Stalin once he rose to power.Trotsky, Leon (June 1932). "Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!". ''

One of the last attempts of the Right Opposition to resist Stalin was the Ryutin Affair in 1932, where a manifesto against the policy of

One of the last attempts of the Right Opposition to resist Stalin was the Ryutin Affair in 1932, where a manifesto against the policy of

In the 1930s, critics of Stalin inside and outside the Soviet Union were under heavy attack by the party. The

In the 1930s, critics of Stalin inside and outside the Soviet Union were under heavy attack by the party. The

Tito and his followers began a political effort to develop a new brand of Socialism that would be both Marxist–Leninist in nature yet anti-Stalinist in practice. The result was the Yugoslav system of socialist

Tito and his followers began a political effort to develop a new brand of Socialism that would be both Marxist–Leninist in nature yet anti-Stalinist in practice. The result was the Yugoslav system of socialist

http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115995 In a secret speech delivered to the 20th party congress in 1956, Khrushchev was critical of the "cult of personality of Stalin" and his selfishness as a leader: During this Cold War era, the American non-communist left (NCL) grew. The NCL was critical of the continuation of Stalinist Communism because of aspects such as famine and repression, and as later discovered, the covert intervention of Soviet state interests in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Members of the NCL were often ex-communists, such as the historian Theodore Draper whose views shifted from socialism to liberalism, and socialists who became disillusioned with the communist movement. Anti-Stalinist Trotskyists also wrote about their experiences during this time, such as

During this Cold War era, the American non-communist left (NCL) grew. The NCL was critical of the continuation of Stalinist Communism because of aspects such as famine and repression, and as later discovered, the covert intervention of Soviet state interests in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Members of the NCL were often ex-communists, such as the historian Theodore Draper whose views shifted from socialism to liberalism, and socialists who became disillusioned with the communist movement. Anti-Stalinist Trotskyists also wrote about their experiences during this time, such as

On Socialism and Sex: An Introduction

''New Politics'' Summer 2008 Vol:XII-1 Whole #: 45 * Maurice Nadeau * Pierre Naville * The New York Intellectuals * Benjamin Péret * Henry Poulaille * David Rousset *

here

) * * Julius Jacobso

''New Politics'', vol. 6, no. 3 (new series), whole no. 23, Summer 1997 * Alan Johnso

''New Politics'', vol. 8, no. 3 (new series), whole no. 31, Summer 2001 * David Renton,

' 2004 Zed Books * Boris Souvarine,

Stalin

', 1935 * Frances Stonor Saunders, '' Who Paid the Piper?: CIA and the Cultural Cold War'', 1999, Granta, (USA: ''The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters'', 2000, The New Press, ). *

Joseph Stalin

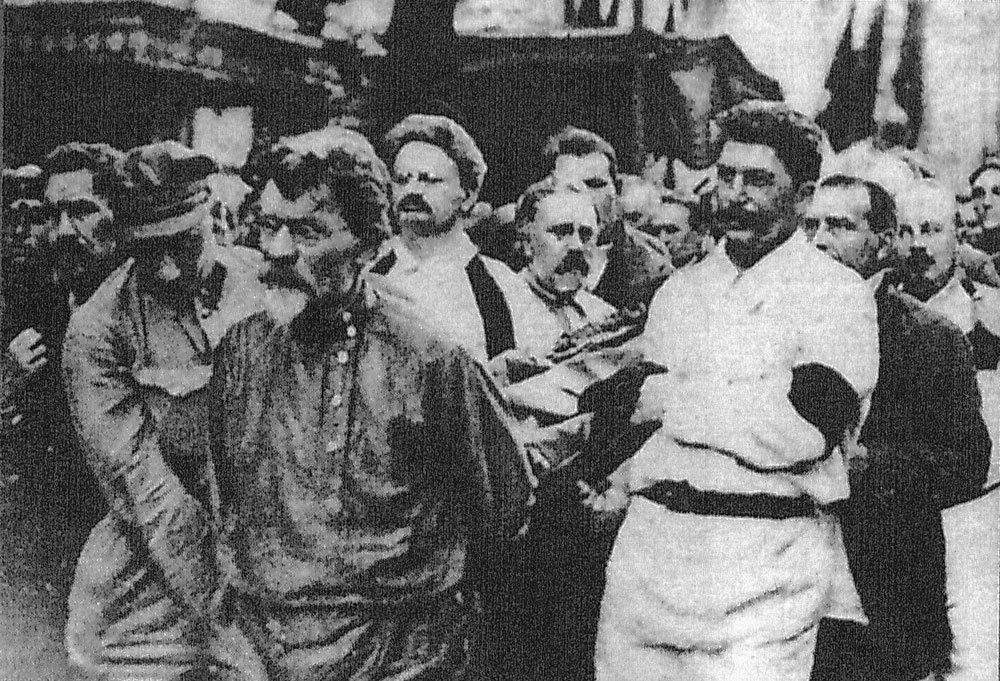

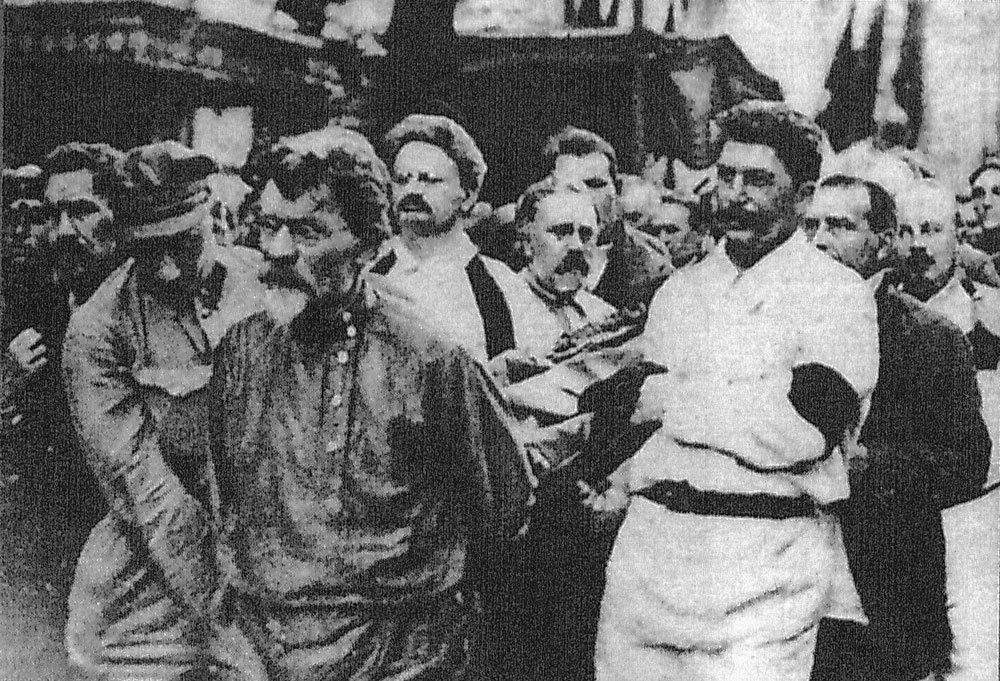

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, Stalinism and the actual system of governance Stalin implemented as leader of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

between 1927 and 1953. This term also refers to the high ranking political figures and governmental programs that opposed Joseph Stalin and his form of communism, like Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

and other left wing traditional Marxists.

In recent years, it may also refer to left and centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

wing opposition to dictatorships

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship are ...

, cults of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

, totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regu ...

and police state

A police state describes a state where its government institutions exercise an extreme level of control over civil society and liberties. There is typically little or no distinction between the law and the exercise of political power by the ...

s, all being features commonly attributed to regimes that took inspiration from Stalinism such as the regimes of Kim Il-sung

Kim Il-sung (; , ; born Kim Song-ju, ; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he ruled from the country's establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994. He held the posts of ...

, Enver Hoxha and others, including in the former Eastern Bloc. Some of the notable movements with the anti-Stalinist left have been Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

and Titoism

Titoism is a political philosophy most closely associated with Josip Broz Tito during the Cold War. It is characterized by a broad Yugoslav identity, workers' self-management, a political separation from the Soviet Union, and leadership in th ...

, anarchism and libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

, left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they reg ...

and libertarian Marxism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

, the Right Opposition

The Right Opposition (, ''Pravaya oppozitsiya'') or Right Tendency (, ''Praviy uklon'') in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a conditional label formulated by Joseph Stalin in fall of 1928 in regards the opposition against certain me ...

within the Communist movement, and democratic socialism and social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

.

Revolutionary era critiques (pre-1924)

A large majority of the political left was initially enthusiastic about theBolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in the revolutionary era. In the beginning, the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and their policies received much support because the movement was originally painted by Lenin and other leaders in a libertarian light. However, as more politically repressive methods were used, the Bolsheviks steadily lost support from many anarchists and revolutionaries. Prominent anarchist communists and libertarian Marxists

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (201 ...

such as Sylvia Pankhurst

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was a campaigning English feminist and socialist. Committed to organising working-class women in London's East End, and unwilling in 1914 to enter into a wartime political truce with t ...

, Rosa Luxemburg, and later, Emma Goldman were among the first left-wing critics of Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

.

Rosa Luxemburg was heavily critical of the methods that Bolsheviks used to seize power in the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

claiming that it was "not a movement of the people but of the bourgeoisie.""The Nationalities Question in the Russian Revolution (Rosa Luxemburg, 1918)". Libcom.org. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2021 Primarily, Luxemburg's critiques were based on the manner in which the Bolsheviks suppressed anarchist movements. In one of her essays published titled, "The Nationalities Question in the Russian Revolution", she explains:"To be sure, in all these cases, it was really not the "people" who engaged in these reactionary policies, but only the bourgeois and petit bourgeois classes, who - in sharpest opposition to their own proletarian masses - perverted the "national right of self-determination" into an instrument of their counter-revolutionary class policies."

Because of her early criticisms toward the Bolsheviks, her legacy was vilified by Stalin once he rose to power.Trotsky, Leon (June 1932). "Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!". ''

Because of her early criticisms toward the Bolsheviks, her legacy was vilified by Stalin once he rose to power.Trotsky, Leon (June 1932). "Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!". ''International Marxist Tendency

The International Marxist Tendency (IMT) is an international Trotskyist political tendency founded by Ted Grant and his supporters following their break with the Committee for a Workers' International in 1992. The organization's website, Marxi ...

''. According to Trotsky, Stalin was "often lying about her and vilifying her" in the eyes of the public.

The relations between the anarchists and the Bolsheviks worsened in Soviet Russia due to the suppression of movements like the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion ( rus, Кронштадтское восстание, Kronshtadtskoye vosstaniye) was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors and civilians against the Bolshevik government in the Russian SFSR port city of Kronstadt. Loc ...

and the Makhnovist movement. The Kronstadt rebellion (March 1921) was a key moment during which many libertarian and democratic leftists broke with the Bolsheviks, laying the foundations for the anti-Stalinist left. The American anti-Stalinist socialist Daniel Bell

Daniel Bell (May 10, 1919 – January 25, 2011) was an American sociologist, writer, editor, and professor at Harvard University, best known for his contributions to the study of post-industrialism. He has been described as "one of the leading A ...

later said:

Every radical generation, it is said, has its Kronstadt. For some it was the Moscow Trials, for others the Nazi-Soviet Pact, for still others Hungary (The Raik Trial or 1956), Czechoslovakia (the defenestration of Masaryk in 1948 or the Prague Spring of 1968), theAnother key anti-Stalinist, Louis Fischer, later coined the term "Kronstadt moment" for this. Like Rosa Luxemburg, Emma Goldman was primarily critical of Lenin's style of leadership, but her focus eventually transferred over to Stalin and his policies as he rose to power. In her essay titled "There Is No Communism in Russia", Goldman details how Stalin "abused the power of his position" and formed a dictatorship. In this text she states:Gulag The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...,Cambodia Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...,Poland Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...(and there will be more to come). My Kronstadt was Kronstadt.

"In other words, by the Central Committee and Politbureau of the Party, both of them controlled absolutely by one man, Stalin. To call such a dictatorship, this personal autocracy more powerful and absolute than any Czar’s, by the name of Communism seems to me the acme of imbecility."Emma Goldman asserted that there was "not the least sign in Soviet Russia even of authoritarian, State Communism." Emma Goldman remained critical of Stalin and the Bolshevik's style of governance up until her death in 1940. Overall, the left communists and anarchists were critical of the statist, repressive, and

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

nature of Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various c ...

which eventually carried over to Stalinism and Stalin's policy in general.

Bolshevik era critiques of Stalin (1924–1930)

One of the last attempts of the Right Opposition to resist Stalin was the Ryutin Affair in 1932, where a manifesto against the policy of

One of the last attempts of the Right Opposition to resist Stalin was the Ryutin Affair in 1932, where a manifesto against the policy of collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

was circulated; it openly called for "The Liquidation of the dictatorship of Stalin and his clique". Later, some rightists joined a secret bloc with Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, Zinoviev and Kamenev in order to oppose Stalin. Historian Pierre Broué stated that it dissolved in early 1933.

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

and Stalin disagreed on issues of industrialization and revolutionary tactics. Trotsky believed that there was a need for super-industrialization while Stalin believed in a rapid surge and collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, as written in his 5-year plan. Trotsky believed an accelerated global surge to be the answer to institute communism globally. Trotsky was critical of Stalin's methods because he believed that the slower pace of collectivization and industrialization to be ineffective in the long run. Trotsky also disagreed with Stalin's thesis of Socialism in One Country

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin encouraged th ...

, believing that the institution of revolution in one state or country would not be as effective as a global revolution.Martin Oppenheimer The “Russian Question” and the U.S. Left, Digger Journal, 2014 He also criticized how the Socialism in One Country

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin encouraged th ...

thesis broke with the internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

traditions of Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

.Harap, Louis (1989). ''The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s''. Guilford Publication. Trotskyists believed that a permanent global revolution was the most effective method to ensure the system of communism was enacted worldwide.

Overall, Trotsky and his followers were very critical of the lack of internal debate and discussion among Stalinist organizations along with their politically repressive methods.

Popular Front era critiques (1930–1939)

In the 1930s, critics of Stalin inside and outside the Soviet Union were under heavy attack by the party. The

In the 1930s, critics of Stalin inside and outside the Soviet Union were under heavy attack by the party. The Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

occurred from 1936-1938 as a result of growing internal tensions between the critics of Stalin but eventually turned into an all-out cleansing of "anti-Soviet elements". A majority of those targeted were peasants and minorities, but anarchists and socialist opponents were also targeted for their criticisms of the repressive political techniques that Stalin used. Many were executed or sent to Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

prison camps extrajudicially. It is estimated that during the Great Purge casualties ranged from 600,000 to over 1 million people.

Concurrently, fascism was rising across Europe. The Communist leadership turned to Popular front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

policy during the 1930s, in which Communists worked with liberal and even conservative allies to defend against a presumed Fascist assault. One of the more notable conflicts can be seen in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

. While the whole left fought alongside the Republican faction, within it there were sharp conflicts between the Communists, on the one hand, and anarchists, Trotskyists and the POUM on the other. Support for the latter became a key issue for the anti-Stalinist left internationally, as exemplified by the ILP Contingent in the International Brigades, George Orwell's book ''Homage to Catalonia

''Homage to Catalonia'' is George Orwell's personal account of his experiences and observations fighting in the Spanish Civil War for the POUM militia of the Republican army.

Published in 1938 (about a year before the war ended) with little c ...

'', the periodical '' Spain and the World'', and various pamphlets by Emma Goldman, Rudolf Rocker

Johann Rudolf Rocker (March 25, 1873 – September 19, 1958) was a German anarchist writer and activist. He was born in Mainz to a Roman Catholic artisan family.

His father died when he was a child, and his mother when he was in his teens, so he ...

and others.

In other countries too, non-Communist left parties competed with Stalinism as the same time as they fought the right. The Three Arrows

The Three Arrows (german: Drei Pfeile) is a social democratic political symbol associated with the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), used in the late history of the Weimar Republic. First conceived for the SPD-dominated Iron Front as ...

symbol was adopted by the German Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

to signify this multi-pronged conflict.

Mid-century critiques (1939–1953)

Josip Broz Tito became one of the most prominent leftist critics of Stalin afterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the policies that were established was originally closely modeled on that of the Soviet Union. In the eyes of many, "Yugoslavia followed perfectly down the path of Soviet Marxism". At the start, Tito was even considered "Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's most faithful pupil". However, as the Yugoslavian Communist Party grew in size and power, it became a secondary communist powerhouse in Europe. This eventually caused Tito to try to operate independently, which created tensions with Stalin and the Soviet Union. In 1948, the two leaders split apart because of Yugoslavian independent foreign policy and ideological differences.

Tito and his followers began a political effort to develop a new brand of Socialism that would be both Marxist–Leninist in nature yet anti-Stalinist in practice. The result was the Yugoslav system of socialist

Tito and his followers began a political effort to develop a new brand of Socialism that would be both Marxist–Leninist in nature yet anti-Stalinist in practice. The result was the Yugoslav system of socialist workers' self-management

Workers' self-management, also referred to as labor management and organizational self-management, is a form of organizational management based on self-directed work processes on the part of an organization's workforce. Self-management is a def ...

. This led to the philosophy of organizing of every production-related activity in society into "self-managed units". This came to be known as Titoism

Titoism is a political philosophy most closely associated with Josip Broz Tito during the Cold War. It is characterized by a broad Yugoslav identity, workers' self-management, a political separation from the Soviet Union, and leadership in th ...

. Tito was critical of Stalin because he believed Stalin became "un-Marxian". In the pamphlet titled "On New Roads to Socialism" one of Tito's high ranking aides states:"The indictment is long indeed: unequal relations with and exploitation of the other socialist countries, un-Marxian treatment of the role of the leader, inequality in pay greater than in bourgeois democracies, ideological promotion of Great Russian nationalism and subordination of other peoples, a policy of division of spheres of influence with the capitalist world, monopolization of the interpretation of Marxism, the abandonment of all democratic forms..."Tito disagreed on the primary characteristics that defined Stalin's policy and style of leadership. Tito wanted to form his own version of "pure" socialism without many of the "un-Marxian" traits of Stalinism. Other foreign leftist critics also came about during this time in Europe and America. Some of these critics include George Orwell, H. N. Brailsford,

Fenner Brockway

Archibald Fenner Brockway, Baron Brockway (1 November 1888 – 28 April 1988) was a British socialist politician, humanist campaigner and anti-war activist.

Early life and career

Brockway was born to W. G. Brockway and Frances Elizabeth Abbey in ...

, the Young People's Socialist League, and later Michael Harrington

Edward Michael Harrington Jr. (February 24, 1928 – July 31, 1989) was an American democratic socialist. As a writer, he was perhaps best known as the author of '' The Other America''. Harrington was also a political activist, theorist, profess ...

, and the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

in Britain. There were also several anti-Stalinist socialists in France, including writers such as Simone Weil

Simone Adolphine Weil ( , ; 3 February 1909 – 24 August 1943) was a French philosopher, mystic, and political activist. Over 2,500 scholarly works have been published about her, including close analyses and readings of her work, since 1995.

...

and Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

as well as the group around Marceau Pivert

Marceau Pivert (2 October 1895, Montmachoux, Seine-et-Marne – 3 June 1958, Paris) was a French schoolteacher, trade unionist, socialist militant, and journalist. He was an alumnus of the École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud.

SFIO

Act ...

.

In America, the New York Intellectuals around the journals ''New Leader

''The New Leader'' (1924–2010) was an American political and cultural magazine.

History

''The New Leader'' began in 1924 under a group of figures associated with the Socialist Party of America, such as Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas. It was p ...

'', ''Partisan Review

''Partisan Review'' (''PR'') was a small-circulation quarterly "little magazine" dealing with literature, politics, and cultural commentary published in New York City. The magazine was launched in 1934 by the Communist Party USA–affiliated Joh ...

,'' and ''Dissent

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

'' were among other critics. In general, these figures criticized Soviet Communism as a form of "totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regu ...

which in some ways mirrored fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

." A key text for this movement was '' The God That Failed'', edited by British socialist Richard Crossman in 1949, featuring contributions by Louis Fischer, André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anticolonialism ...

, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

, Ignazio Silone

Secondino Tranquilli (1 May 1900 – 22 August 1978), known by the pseudonym Ignazio Silone (, ), was an Italian political leader, novelist, and short-story writer, world-famous during World War II for his powerful anti-fascist novels. He was no ...

, Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

and Richard Wright, about their journeys to anti-Stalinism.

New Party Era critiques (1953–1991)

Following thedeath of Joseph Stalin

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

, many prominent leaders of Stalin's cabinet sought to seize power. As a result, a Soviet Triumvirate was formed between Lavrenty Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the p ...

, and Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

. The primary goal of the new leadership was to ensure stability in the country while leadership positions within the government were sorted out. Some of the new policy implemented that was antithetical of Stalinism included policy that was free from terror, that decentralized power, and collectivized leadership. After this long power struggle within the Soviet government, Nikita Khrushchev came into power. Once in power, Khrushchev was quick to denounce Stalin and his methods of governance.“Khrushchev's Secret Speech, 'On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,' Delivered at the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,” February 25, 1956, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, From the Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 84th Congress, 2nd Session (May 22, 1956-June 11, 1956), C11, Part 7 (June 4, 1956), pp. 9389-9403. "Comrades, the cult of the individual acquired such monstrous size chiefly because Stalin himself, using all conceivable methods, supported the glorification of his own person. This is supported by numerous facts."Khrushchev also revealed to the congress the truth behind Stalin's methods of repression. In addition, he explained that Stalin had rounded up "thousands of people and sent them into a huge system of political work camps" called

gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

s. The truths revealed in this speech came to the surprise of many, but this fell into the plan of Khrushchev. This speech tainted Stalin's name which resulted in a significant loss of faith in his policy from government officials and citizens. During this Cold War era, the American non-communist left (NCL) grew. The NCL was critical of the continuation of Stalinist Communism because of aspects such as famine and repression, and as later discovered, the covert intervention of Soviet state interests in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Members of the NCL were often ex-communists, such as the historian Theodore Draper whose views shifted from socialism to liberalism, and socialists who became disillusioned with the communist movement. Anti-Stalinist Trotskyists also wrote about their experiences during this time, such as

During this Cold War era, the American non-communist left (NCL) grew. The NCL was critical of the continuation of Stalinist Communism because of aspects such as famine and repression, and as later discovered, the covert intervention of Soviet state interests in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Members of the NCL were often ex-communists, such as the historian Theodore Draper whose views shifted from socialism to liberalism, and socialists who became disillusioned with the communist movement. Anti-Stalinist Trotskyists also wrote about their experiences during this time, such as Irving Howe

Irving Howe (; June 11, 1920 – May 5, 1993) was an American literary and social critic and a prominent figure of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Early years

Howe was born as Irving Horenstein in The Bronx, New York. He was the son of ...

and Lewis Coser

Lewis Alfred Coser (27 November 1913 in Berlin – 8 July 2003 in Cambridge, Massachusetts) was a German-American sociologist, serving as the 66th president of the American Sociological Association in 1975.

Biography

Born in Berlin as Ludwig Co ...

. These perspectives inspired the creation of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), as well as international journals like '' Der Monat'' and ''Encounter

Encounter or Encounters may refer to:

Film

*''Encounter'', a 1997 Indian film by Nimmala Shankar

* ''Encounter'' (2013 film), a Bengali film

* ''Encounter'' (2018 film), an American sci-fi film

* ''Encounter'' (2021 film), a British sci-fi film

* ...

''; it also influenced existing publications such as the ''Partisan Review

''Partisan Review'' (''PR'') was a small-circulation quarterly "little magazine" dealing with literature, politics, and cultural commentary published in New York City. The magazine was launched in 1934 by the Communist Party USA–affiliated Joh ...

''. According to John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr

Harvey Elliott Klehr (born December 25, 1945) is a professor of politics and history at Emory University. Klehr is known for his books on the subject of the American Communist movement, and on Soviet espionage in America (many written jointly wit ...

, the CCF was covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) to support intellectuals with pro-democratic and anti-communist stances. The Communist Party USA lost much of its influence in the first years of the Cold War due to the revelation of Stalinist crimes by Khrushchev. Although the Soviet Communist Party was no longer officially Stalinist, the Communist Party USA received a substantial subsidy from the USSR from 1959 until 1989, and consistently supported official Soviet policies such as intervention in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The Soviet funding ended in 1989 when Gus Hall

Gus Hall (born Arvo Kustaa Halberg; October 8, 1910 – October 13, 2000) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and a perennial candidate for president of the United States. He was the Communist Party nominee in the ...

condemned the market initiatives of Mikhail Gorbachev.

From the late 1950s, several European socialist and communist parties, such as in Denmark and Sweden, shifted away from orthodox communism which they connected to Stalinism that was in recent history. The emergence of the New Left was influenced to some degree by the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 and increasing amount of information available about Stalinist terror. Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

criticized Soviet communism, while many leftists saw the Soviet Union as emblematic of "state capitalism." After Stalin's death and the Khrushchev Thaw, study and opposition to Stalinism became a part of historiography. The historian Moshe Lewin cautioned not to categorize the entire history of the Soviet Union as Stalinist, but also emphasized that Stalin's bureaucracy had permanently established "bureaucratic absolutism," resembling old monarchy, in the Soviet Union.

Post-Soviet critiques (1991–present)

After the fall ofGorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Comm ...

and the Soviet Union in 1991

File:1991 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Boris Yeltsin, elected as Russia's first president, waves the new flag of Russia after the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, orchestrated by Soviet hardliners; Mount Pinatubo erupts in the Phi ...

, the anti-Stalinist movement grew rapidly.

In the early 1990s, many new anti-Stalinist left movements emerged in the former Soviet bloc as a result of failed elections and Boris Yeltsin’s Palace Coup. When this seizure of power occurred, more than thirty electoral blocs set out to contest the election.Andy Blunden 1993 The Class Struggle in Russia: III: The Left in Russia ''Stalinism: It's 'sic''Origin and Future''. Some of these anti-Stalinist groups were: Choice of Russia, the Civic Union for Stability, Justice & Progress, Constructive Ecological Movement, Russian Democratic Reform Movement, Dignity and Mercy, and Women of Russia. Even though these movements were not successful in contesting the election, they displayed how there was still a strong support of anti-Stalinism after the collapse of the Soviet Union. These movements were all critical of Stalinist policy and some even called it an "unmitigated disaster for socialists" Hillel H. Ticktin End of Stalinism, Beginning of Marxism May–June 1992, Against the Current 38

Notable figures

*Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

* Clement Attlee

* Colette Audry

* Daniel Bell

Daniel Bell (May 10, 1919 – January 25, 2011) was an American sociologist, writer, editor, and professor at Harvard University, best known for his contributions to the study of post-industrialism. He has been described as "one of the leading A ...

* André Breton

*Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

* Milovan Djilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democrat ...

* Daniel Guérin

* Sidney HookMichael HOCHGESCHWENDER "The cultural front of the Cold War: the Congress for cultural freedom as an experiment in transnational warfare" ''Ricerche di storia politica'', issue 1/2003, pp. 35-60

* Irving Howe

Irving Howe (; June 11, 1920 – May 5, 1993) was an American literary and social critic and a prominent figure of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Early years

Howe was born as Irving Horenstein in The Bronx, New York. He was the son of ...

* CLR James

* Lucien Laurat

* Claude Lefort

Claude Lefort (; ; 21 April 1924 – 3 October 2010) was a French philosopher and activist.

He was politically active by 1942 under the influence of his tutor, the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (whose posthumous publications Lefort late ...

* Marcel Martinet Marcel Martinet (Dijon, 22 August 1887 – Saumur, 18 February 1944) was a French pacifist socialist revolutionary militant and a Proletarian literature, prolétarian writer.

Life

Martinet, a Communist and pacifist, opposed the First World War from ...

* Dwight MacDonald

* Mary McCarthy

* Claude McKayChristopher PhelpOn Socialism and Sex: An Introduction

''New Politics'' Summer 2008 Vol:XII-1 Whole #: 45 * Maurice Nadeau * Pierre Naville * The New York Intellectuals * Benjamin Péret * Henry Poulaille * David Rousset *

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and lit ...

* Victor Serge

Victor Serge (; 1890–1947), born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich (russian: Ви́ктор Льво́вич Киба́льчич), was a Russian revolutionary Marxist, novelist, poet and historian. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks fi ...

* Ota Šik

* George Orwell

* IF Stone

* Carlo Tresca

See also

* Anti-Leninism **Anti-communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

* De-Stalinization

* Eurocommunism

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more rel ...

* Harvill Secker

* Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, ''Yevreysky antifashistsky komitet'' yi, יידישער אנטי פאשיסטישער קאמיטעט, ''Yidisher anti fashistisher komitet''., abbreviated as JAC, ''YeAK'', was an organization that was created i ...

* Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks

The left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks, known in anarchist literature as the Third Russian Revolution, were a series of rebellions, uprisings, and revolts against the Bolsheviks by oppositional left-wing organizations and groups that st ...

* Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

* New Left

* Red fascism

Red fascism is a term equating Stalinism, Maoism, and other variants of Marxism–Leninism with fascism. Accusations that the leaders of the Soviet Union during the Stalin era acted as "red fascists" were commonly stated by anarchists, left commun ...

* '' Tankie'' – pejorative term used by anti-authoritarian socialists

References

Further reading

*Ian Birchall

Ian Birchall (born 1939) is a British Marxist historian and translator, a former member of the Socialist Workers Party and author of numerous articles and books, particularly relating to the French Left. Formerly Senior Lecturer in French at Mid ...

''Sartre Against Stalinism''. Berghahn Books. (See reviehere

) * * Julius Jacobso

''New Politics'', vol. 6, no. 3 (new series), whole no. 23, Summer 1997 * Alan Johnso

''New Politics'', vol. 8, no. 3 (new series), whole no. 31, Summer 2001 * David Renton,

' 2004 Zed Books * Boris Souvarine,

Stalin

', 1935 * Frances Stonor Saunders, '' Who Paid the Piper?: CIA and the Cultural Cold War'', 1999, Granta, (USA: ''The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters'', 2000, The New Press, ). *

Alan Wald

Alan Maynard Wald (born June 1, 1946) is an American professor emeritus of English Literature and American Culture at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and writer of 20th-century American literature who focuses on Communist writers; he is an ...

''The New York Intellectuals, The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left From the 1930s to the 1980s''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. 440 pp (See review by Paul LeBlancbr>hereExternal links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Stalinist Left Communism Eponymous political ideologies History of socialism Marxism Political ideologies Political movements Socialism Joseph Stalin