Anti-German sentiment on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-German sentiment (also known as Anti-Germanism, Germanophobia or Teutophobia) is opposition to or fear of

According to Alfred Vagts "

According to Alfred Vagts "

In 1914, when Germany invaded neutral Belgium and northern France, its army officers accused many thousands of Belgian and French civilians of being

In 1914, when Germany invaded neutral Belgium and northern France, its army officers accused many thousands of Belgian and French civilians of being

The

The

Internment camps across Canada opened in 1915 and 8,579 "enemy aliens" were held there until the end of the war; many were German speaking immigrants from Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Ukraine. Only 3,138 were classed as prisoners of war; the rest were civilians.

Built in 1926, the Waterloo Pioneer Memorial Tower in rural Kitchener, Ontario, commemorates the settlement by the Pennsylvania Dutch (actually ''Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch'' or ''German'') of the Grand River area in the 1800s in what later became

Internment camps across Canada opened in 1915 and 8,579 "enemy aliens" were held there until the end of the war; many were German speaking immigrants from Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Ukraine. Only 3,138 were classed as prisoners of war; the rest were civilians.

Built in 1926, the Waterloo Pioneer Memorial Tower in rural Kitchener, Ontario, commemorates the settlement by the Pennsylvania Dutch (actually ''Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch'' or ''German'') of the Grand River area in the 1800s in what later became

In Australia, an official proclamation of 10 August 1914 required all German citizens to register their domiciles at the nearest police station and to notify authorities of any change of address. Under the later Aliens Restriction Order of 27 May 1915, enemy aliens who had not been interned had to report to the police once a week and could only change address with official permission. An amendment to the Restriction Order in July 1915 prohibited enemy aliens and naturalized subjects from changing their name or the name of any business they ran. Under the War Precautions Act of 1914 (which survived the First World War), publication of German language material was prohibited and schools attached to

In Australia, an official proclamation of 10 August 1914 required all German citizens to register their domiciles at the nearest police station and to notify authorities of any change of address. Under the later Aliens Restriction Order of 27 May 1915, enemy aliens who had not been interned had to report to the police once a week and could only change address with official permission. An amendment to the Restriction Order in July 1915 prohibited enemy aliens and naturalized subjects from changing their name or the name of any business they ran. Under the War Precautions Act of 1914 (which survived the First World War), publication of German language material was prohibited and schools attached to

After the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram partly sparked the American declaration of war against Imperial Germany in April 1917, German Americans were sometimes accused of being too sympathetic to Germany. Former president

After the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram partly sparked the American declaration of war against Imperial Germany in April 1917, German Americans were sometimes accused of being too sympathetic to Germany. Former president  When the United States entered the war in 1917, some German Americans were looked upon with suspicion and attacked regarding their loyalty. Some aliens were convicted and imprisoned on charges of sedition, for refusing to swear allegiance to the United States war effort.

In

When the United States entered the war in 1917, some German Americans were looked upon with suspicion and attacked regarding their loyalty. Some aliens were convicted and imprisoned on charges of sedition, for refusing to swear allegiance to the United States war effort.

In

"Anti-German hysteria swept Cincinnati in 1917"

. ''The Cincinnati Enquirer'', 6 June 2012. Accessed 15 February 2013. In Chicago Lubeck, Frankfort, and Hamburg Streets were renamed Dickens, Charleston, and Shakespeare Streets.Jack Simpson

"German Street Name Changes in Bucktown, Part I"

Newberry Library. In New Orleans, Berlin Street was renamed in honor of General Pershing, head of the American Expeditionary Force. In Indianapolis, Bismarck Avenue and Germania Street were renamed Pershing Avenue and Belleview Street, respectively in 1917, Brooklyn’s Hamburg Avenue was renamed Wilson Avenue. Many businesses changed their names. In Chicago, German Hospital became Grant Hospital; likewise the German Dispensary and the German Hospital in New York City were renamed

by

/ref> Estimates of the total number of dead range from 500,000 to 2,000,000, and the higher figures include "unsolved cases" of persons reported missing and presumed dead. Many German civilians were sent to internment and labor camps, where they died.

After the separation into two countries after World War II,

''New York Times'', 8 February 1995. In the first half of the 17th century, the Republic saw a major spike in German immigrants including common laborers (so-called hannekemaaiers), persecuted

online

* Dekker, Henk, and Lutsen B. Jansen. "Attitudes and stereotypes of young people in the Netherlands with respect to Germany." in ''The puzzle of Integration: European Yearbook on Youth Policy and Research'' 1 (1995): 49–61

excerpt

* DeWitt, Petra. ''Degrees of Allegiance: Harassment and Loyalty in Missouri's German-American Community during World War I'' (Ohio University Press, 2012)., on USA * Ellis, M. and P. Panayi. "German Minorities in World War I: A Comparative Study of Britain and the USA", '' Ethnic and Racial Studies'' 17 (April 1994): 238–259. * Kennedy, Paul M. "Idealists and realists: British views of Germany, 1864–1939." ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' 25 (1975): 137–156

online

* Kennedy, Paul M. ''The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860-1914'' (1980); 604pp, major scholarly study. * Lipstadt, Deborah E. "America and the Memory of the Holocaust, 1950–1965." ''Modern Judaism'' (1996) 16#3 pp: 195–214

online

* Panayi, Panikos, ed. ''Germans as Minorities during the First World War: A Global Comparative Perspective'' (2014

excerpt

covers Britain, Belgium, Italy, Russia, Greece, USA, Africa, New Zealand * Panayi, Panikos. "Anti-German Riots in London during the First World War." ''German History'' 7.2 (1989): 184+. * Rüger, Jan. "Revisiting the Anglo-German Antagonism." ''Journal of Modern History'' 83.3 (2011): 579-617. in JSTOR * Scully, Richard. ''British Images of Germany: Admiration, Antagonism & Ambivalence, 1860–1914'' (2012) * Stafford, David A.T. "Spies and Gentlemen: The Birth of the British Spy Novel, 1893-1914." ''Victorian Studies'' (1981): 489-509

online

* Stephen, Alexander. ''Americanization and anti-Americanism : the German encounter with American culture after 1945'' (2007

online

* Tischauser, Leslie V. ''The Burden of Ethnicity: The German Question in Chicago, 1914–1941''. (1990). * Vagts, Alfred. "Hopes and Fears of an American-German War, 1870-1915 I" ''Political Science Quarterly'' 54#4 (1939), pp. 514-53

online

"Hopes and Fears of an American-German War, 1870-1915 II." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 55.1 (1940): 53-7

online

* Wingfield, Nancy M. "The Politics of Memory: Constructing National Identity in the Czech Lands, 1945 to 1948." ''East European Politics & Societies'' (2000) 14#2 pp: 246–267. Argues that anti-German attitudes were paramount * Yndigegn, Carsten. "Reviving Unfamiliarity—The Case of Public Resistance to the Establishment of the Danish–German Euroregion." European Planning Studies 21.1 (2013): 58–74

Abstract

"Nobody Would Eat Kraut": Lola Gamble Clyde on Anti-German Sentiment in Idaho During World War I (Oral history courtesy of Latah County Historical Society)"Get the Rope!" Anti-German Violence in World War I-era Wisconsin (from History Matters, a project of the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning)"We Had to Be So Careful" A German Farmer's Recollections of Anti-German Sentiment in World War I (Oral history courtesy of Latah County Historical Society)Article from Allan Hall

in ''

Newspaper articles from 1918, describing the lynching of Robert Prager in Collinsville, Illinois

(Bloomington, Illinois, newspaper)

(Bloomington, Illinois, newspaper) {{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-German Sentiment 19th-century introductions

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, its inhabitants

Domicile is relevant to an individual's "personal law," which includes the law that governs a person's status and their property. It is independent of a person's nationality. Although a domicile may change from time to time, a person has only one ...

, its culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

, or its language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

. Its opposite is Germanophilia

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of German culture, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German citizen. The love of the ''Ge ...

.

Anti-German sentiment largely began with the mid-19th-century unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of t ...

, which made the new nation a rival to the great powers of Europe on economic, cultural, geopolitical, and military grounds. However, the German atrocities during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

greatly strengthened anti-German sentiment.

Before 1914

United States

In the 19th century, the mass influx of German immigrants made them the largest group of Americans by ancestry today. This migration resulted in nativist reactionary movements not unlike those of the contemporary Western world. These would eventually culminate in 1844 with the establishment of the American Party, which had an openlyxenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

stance. One of many incidents described in a 19th century account included the blocking of a funeral procession in New York by a group who proceeded to hurl insults at the pallbearers. Incidents such as these led to more meetings of Germans who would eventually establish fraternal groups such as the Sons of Hermann

The Order of the Sons of Hermann (german: Der Orden der Hermanns-Soehne, also known as Hermann Sons ( ''Hermannssöhne'' ), is a mutual aid society for German immigrants that was formed in New York, New York on July 20, 1840,Fritz Schilo"Sons ...

in 1840, having been founded as a means to "improve and foster German customs and the spread of benevolence among Germans in the United States".

Russia

In the 1860s, Russia experienced an outbreak of Germanophobia, mainly restricted to a small group of writers inSt. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

who had united around a left-wing newspaper. It began in 1864 with the publication of an article by a writer (using the pseudonym "Shedoferotti") who proposed that Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

be given autonomy and that the privileges of the Baltic German nobility

Baltic German nobility was a privileged social class in the territories of today's Estonia and Latvia. It existed continuously since the Northern Crusades and the medieval foundation of Terra Mariana. Most of the nobility were Baltic Germans, but ...

in the Baltic governorates

The Baltic governorates (russian: Прибалтийские губернии), originally the Ostsee governorates (german: Ostseegouvernements, russian: Остзейские губернии), was a collective name for the administrative units ...

and Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

be preserved. Mikhail Katkov

Mikhail Nikiforovich Katkov (russian: Михаи́л Ники́форович Катко́в; 13 February 1818 – 1 August 1887) was a conservative Russian journalist influential during the reign of tsar Alexander III. He was a proponent of Rus ...

published a harsh criticism of the article in the ''Moscow News

''The Moscow News'', which began publication in 1930, was Russia's oldest English-language newspaper. Many of its feature articles used to be translated from the Russian language '' Moskovskiye Novosti.''

History Soviet Union

In 1930 ''The ...

'', which in turn caused a flood of angry articles in which Russian writers expressed their irritation with Europeans, some of which featured direct attacks on Germans.

The following year, 1865, the 100th anniversary of the death of Mikhail Lomonosov was marked throughout the Russian Empire. Articles were published mentioning the difficulties Lomonosov had encountered from the foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across ...

, most of whom had been of German descent. The authors then criticized contemporary German scholars for their neglect of the Russian language and for printing articles in foreign languages while receiving funds from the Russian people. It was further suggested by some writers that Russian citizens of German origin who did not speak Russian and follow the Orthodox faith should be considered foreigners. It was also proposed that people of German descent be forbidden from holding diplomatic posts as they might not have "solidarity with respect to Russia".

Despite the press campaign against Germans, Germanophobic feelings did not develop in Russia to any widespread extent, and died out, due to the Imperial family's German roots and the presence of many German names in the Russian political elite.

Great Britain

Negative comments about Germany had begun to appear in Britain in the 1870s, following the Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71. The British war planners considered how to stop a possible invasion.Fiction

Britain the island nation feared invasion, leading to the popularity of theinvasion novel

Invasion literature (also the invasion novel) is a literary genre that was popular in the period between 1871 and the World War I, First World War (1914–1918). The invasion novel first was recognized as a literary genre in the UK, with the nov ...

.

According to Alfred Vagts "

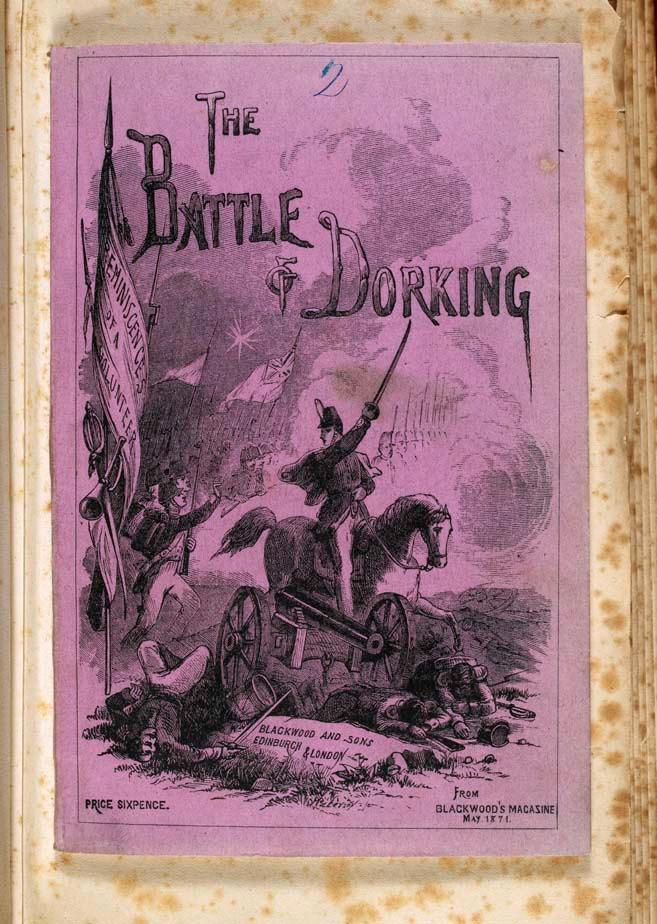

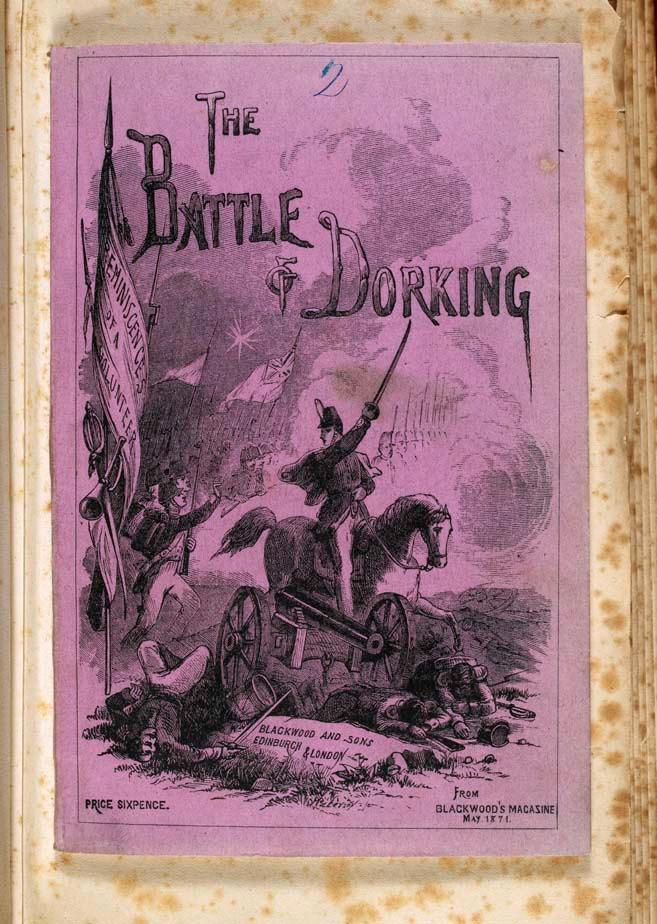

According to Alfred Vagts "The Battle of Dorking

''The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer'' is an 1871 novella by George Tomkyns Chesney, starting the genre of invasion literature and an important precursor of science fiction. Written just after the Prussian victory in the Franc ...

":appeared first in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' in the summer of 1871, at a time when the German Crown Prince and his English wifeNewspaper publisher Lordhe daughter of Queen Victoria He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...were visiting England. Impressed by the late German victories, the author, a Colonel Chesney, who remained anonymous for some time, told the story of how England, in 1875, would be induced by an insurrection of the natives in India, disturbances in Ireland, and a conflict with the United States threatening Canadian security, to employ her navy and standing army far from her own shores; in spite of this dangerous position England, on account of a quarrel with Germany over Denmark, would declare war on Germany. The latter would land an army in England which would conquer the remaining parts of the British army and the Volunteers, who would join it at Dorking, and would force upon England a disastrous peace.

Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe

Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (15 July 1865 – 14 August 1922), was a British newspaper and publishing magnate. As owner of the '' Daily Mail'' and the ''Daily Mirror'', he was an early developer of popular journa ...

in 1894 commissioned author William Le Queux

William Tufnell Le Queux ( , ; 2 July 1864 – 13 October 1927) was an Anglo-French journalist and writer. He was also a diplomat (honorary consul for San Marino), a traveller (in Europe, the Balkans and North Africa), a flying buff who officia ...

to write the serial novel '' The Great War in England in 1897'', which featured France and Russia combining forces to crush Britain. Happily German intervention on Britain's side turned back France and Russia. Twelve years later, however, Harmsworth asked him to reverse enemies, making Germany the villain. The result was the bestselling '' The Invasion of 1910'', which originally appeared in serial form in the '' Daily Mail'' in 1906. Harmsworth now used his newspapers like "Daily Mail" or "The Times" to attack Berlin, inducing an atmosphere of paranoia, mass hysteria and Germanophobia that would climax in the Naval Scare of 1908–09.

"Made in Germany" as a warning label

German food such as the sausage was deprecated by Germanophobes. In the late 19th century, the label ''Made in Germany

Made in Germany is a merchandise mark indicating that a product has been manufactured in Germany.

History

The label was introduced in Britain by the '' Merchandise Marks Act 1887'', to mark foreign produce more obviously, as foreign manufactur ...

'' was introduced. The label was originally introduced in Britain by the ''Merchandise Marks Act 1887

The Merchandise Marks Act 1887 (50 & 51 Vict. c. 28) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

The Act stopped foreign manufacturers from falsely claiming that their goods were British-made and selling them in Britain and Europe on that ...

'', to mark foreign produce more obviously, as foreign manufactures had been falsely marking inferior goods with the marks of renowned British manufacturing companies and importing them into the United Kingdom. Most of these were found to be originating from Germany, whose government had introduced a protectionist policy to legally prohibit the import of goods in order to build up domestic industry (Merchandise Marks Act - Oxford University Press).

German immigrants

In the 1890s, German immigrants in Britain were the target of "some hostility". Joseph Bannister believed that German residents in Britain were mostly "gambling-house keepers, hotel-porters, barbers, 'bullies', runaway conscripts, bath-attendants, street musicians, criminals, bakers, socialists, cheap clerks, etc". Interviewees for the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration believed that Germans were involved in prostitution and burglary, and many people also viewed Germans working in Britain as threatening the livelihood of Britons by being willing to work for longer hours.=South Africa

= Anti-German hostility deepened since early 1896 after the Kruger telegram ofKaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

, in which he congratulated President Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and President of the South African Republic (or ...

of the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

on repelling the British Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson, under the employment of Cecil ...

. Attacks on Germans in London were reported in the German press at the time but do not appear to have actually occurred. The '' Saturday Review'' suggested "be ready to fight Germany, as ''Germania delenda est''" ("Germany is to be destroyed"), a reference to the coda against the Carthaginians used by Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor ( la, Censorius), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write his ...

during the Roman Republic. The Kaiser's reputation was further degraded by his angry tirade and the Daily Telegraph Affair.

1900-1914

Following the signing of theEntente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

alliance in 1904 between Britain and France, official relationships cooled as did popular attitudes towards Germany and German residents in Britain. A fear of German militarism replaced a previous admiration for German culture and literature. At the same time, journalists produced a stream of articles on the threat posed by Germany. In the Daily Telegraph Affair of 1908–1909, the Kaiser--although he was a grandson of Queen Victoria-- humiliated himself and further soured relations by his intemperate attacks on Britain.

Articles in Harmsworth's ''Daily Mail'' regularly advocated anti-German sentiments throughout the 20th century, telling their readers to refuse service at restaurants by Austrian or German waiters on the claim that they were spies and told them that if a German-sounding waiter claimed to be Swiss that they should demand to see the waiter's passport. In 1903, Erskine Childers published ''The Riddle of the Sands: A Record of Secret Service'' a novel in which two Englishmen uncover a plot by Germany to Invade England; it was later made into a 1979 film The Riddle of the Sands

''The Riddle of the Sands: A Record of Secret Service'' is a 1903 novel by Erskine Childers. The book, which enjoyed immense popularity in the years before World War I, is an early example of the espionage novel and was extremely influenti ...

.

At the same time, conspiracy theories were concocted combining Germanophobia with antisemitism, concerning the supposed foreign control of Britain, some of which blamed Britain's entry into the Second Boer War on international financiers "chiefly German in origin and Jewish in race". Most of these ideas about German-Jewish conspiracies originated from right-wing figures such as Arnold White

Arnold Henry White (1 February 1848 – 5 February 1925) was an English journalist and antisemitic campaigner against immigration.G. R. Searle, �White, Arnold Henry (1848–1925)��, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University P ...

, Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

, and Leo Maxse, the latter using his publication the ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief ...

'' to spread them.

First World War

In 1914, when Germany invaded neutral Belgium and northern France, its army officers accused many thousands of Belgian and French civilians of being

In 1914, when Germany invaded neutral Belgium and northern France, its army officers accused many thousands of Belgian and French civilians of being francs-tireurs

(, French for "free shooters") were irregular military formations deployed by France during the early stages of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). The term was revived and used by partisans to name two major French Resistance movements set ...

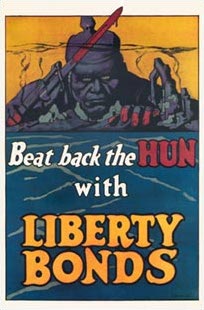

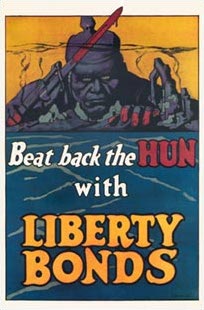

and executed 6,500 of them. These acts were used to encourage anti-German sentiments and the Allied Powers produced propaganda depicting Germans as ''Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

'' capable of infinite cruelty and violence.

Great Britain

In Great Britain, anti-German feeling led to infrequent rioting, assaults on suspected Germans and the looting of stores owned by people with German-sounding names, occasionally even taking on an antisemitic tone. Increasing anti-German hysteria even threw suspicion upon the British royal family.King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

was persuaded to change his German name of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (german: Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha), or Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (german: Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, links=no ), was an Ernestine, Thuringian duchy ruled by a branch of the House of Wettin, consisting of territories in the present- ...

to Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

and relinquish all German titles and styles on behalf of his relatives who were British subjects. Prince Louis of Battenberg

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Alexander Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven, (24 May 185411 September 1921), formerly Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg, was a British naval officer and German prince related by marriage to the British ...

was not only forced to change his name to Mountbatten, he was forced to resign as First Sea Lord, the most senior position in the Royal Navy.

The

The German Shepherd

The German Shepherd or Alsatian is a German breed of working dog of medium to large size. The breed was developed by Max von Stephanitz using various traditional German herding dogs from 1899.

It was originally bred as a herding dog, for ...

breed of dog was renamed to the euphemistic "Alsatian"; the English Kennel Club only re-authorised the use of 'German Shepherd' as an official name in 1977. The German biscuit was re-named the Empire biscuit

An Empire biscuit (Imperial biscuit, Imperial cookie, double biscuit, German biscuit, Belgian biscuit, double shortbread, Empire cookie or biscuit bun) is a sweet biscuit eaten in Scotland, and other Commonwealth countries. It is popular in Northe ...

.

Several streets in London which had been named after places in Germany or notable Germans had their names changed. For instance, ''Berlin Road'' in Catford

Catford is a district in south east London, England, and the administrative centre of the London Borough of Lewisham. It is southwest of Lewisham itself, mostly in the Rushey Green and Catford South wards. The population of Catford, includ ...

was renamed ''Canadian Avenue'', and ''Bismarck Road'' in Islington was renamed ''Waterlow Road''.

Attitudes to Germany were not entirely negative among British troops fighting on the Western Front; the British writer Nicholas Shakespeare quotes this statement from a letter written by his grandfather during the First World War in which he says he would rather fight the French and describes German bravery:

Robert Graves who, like the King, also had German relatives, wrote shortly after the war during his time at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

as an undergraduate that:

Canada

In Canada, there was some anti-German sentiment in Germanic communities, including Berlin, Ontario (Kitchener, Ontario

)

, image_flag = Flag of Kitchener, Ontario.svg

, image_seal = Seal of Kitchener, Canada.svg

, image_shield=Coat of arms of Kitchener, Canada.svg

, image_blank_emblem = Logo of Kitchener, Ontario.svg

, blank_emblem_type = ...

) in Waterloo County, Ontario

Waterloo County was a county in the Canadian province of Ontario from 1853 until 1973. It was the direct predecessor of the Regional Municipality of Waterloo.

Situated on a subset of land within the Haldimand Tract, the traditional territory o ...

, before and the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and some cultural sanctions. There were anti-German riots in Victoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of the Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Greater Victoria area has a population of 397,237. The ...

, and Calgary, Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, in the first years of the war.

It was this anti-German sentiment that precipitated the Berlin to Kitchener name change

The city of Berlin, Ontario, changed its name to Kitchener by referendum in May and June 1916. Named in 1833 after the capital of Prussia and later the German Empire, the name Berlin became unsavoury for residents after Britain and Canada's e ...

in 1916. The city was named after Lord Kitchener, famously pictured on the "Lord Kitchener Wants You

Lord Kitchener Wants You is a 1914 advertisement by Alfred Leete which was developed into a recruitment poster. It depicted Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, above the words "WANTS YOU". Kitchener, wearing the cap of a B ...

" recruiting posters. Several streets in Toronto that had previously been named for Liszt, Humboldt, Schiller, Bismarck, etc., were changed to names with strong British associations, such as Balmoral.

The Governor General of Canada, the Duke of Connaught

Duke of Connaught and Strathearn was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom that was granted on 24 May 1874 by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to her third son, Prince Arthur. At the same time, he was also ...

, while visiting Berlin, Ontario, in May 1914, had discussed the importance of Canadians of German ethnicity (regardless of their origin) in a speech: "It is of great interest to me that many of the citizens of Berlin are of German descent. I well know the admirable qualities – the thoroughness, the tenacity, and the loyalty of the great Teutonic Race, to which I am so closely related. I am sure that these inherited qualities will go far in the making of good Canadians and loyal citizens of the British Empire".

Some immigrants from Germany who considered themselves Canadians but were not yet citizens, were detained in internment camps during the War. In fact, by 1919 most of the population of Kitchener, Waterloo, and Elmira in Waterloo County, Ontario

Waterloo County was a county in the Canadian province of Ontario from 1853 until 1973. It was the direct predecessor of the Regional Municipality of Waterloo.

Situated on a subset of land within the Haldimand Tract, the traditional territory o ...

, were Canadian.

The German-speaking Mennonites were pacifist so they could not enlist and the few who had immigrated from Germany (not born in Canada) could not morally fight against a country that was a significant part of their heritage.

News reports during the war years indicate that "A Lutheran minister was pulled out of his house ... he was dragged through the streets. German clubs were ransacked through the course of the war. It was just a really nasty time period." Someone stole the bust of Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

from Victoria Park and dumped it into a lake; soldiers vandalized German stores. History professor Mark Humphries summarized the situation:

A document in the Archives of Canada makes the following comment: "Although ludicrous to modern eyes, the whole issue of a name for Berlin highlights the effects that fear, hatred and nationalism can have upon a society in the face of war."

Internment camps across Canada opened in 1915 and 8,579 "enemy aliens" were held there until the end of the war; many were German speaking immigrants from Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Ukraine. Only 3,138 were classed as prisoners of war; the rest were civilians.

Built in 1926, the Waterloo Pioneer Memorial Tower in rural Kitchener, Ontario, commemorates the settlement by the Pennsylvania Dutch (actually ''Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch'' or ''German'') of the Grand River area in the 1800s in what later became

Internment camps across Canada opened in 1915 and 8,579 "enemy aliens" were held there until the end of the war; many were German speaking immigrants from Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Ukraine. Only 3,138 were classed as prisoners of war; the rest were civilians.

Built in 1926, the Waterloo Pioneer Memorial Tower in rural Kitchener, Ontario, commemorates the settlement by the Pennsylvania Dutch (actually ''Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch'' or ''German'') of the Grand River area in the 1800s in what later became Waterloo County, Ontario

Waterloo County was a county in the Canadian province of Ontario from 1853 until 1973. It was the direct predecessor of the Regional Municipality of Waterloo.

Situated on a subset of land within the Haldimand Tract, the traditional territory o ...

.

Australia

In Australia, an official proclamation of 10 August 1914 required all German citizens to register their domiciles at the nearest police station and to notify authorities of any change of address. Under the later Aliens Restriction Order of 27 May 1915, enemy aliens who had not been interned had to report to the police once a week and could only change address with official permission. An amendment to the Restriction Order in July 1915 prohibited enemy aliens and naturalized subjects from changing their name or the name of any business they ran. Under the War Precautions Act of 1914 (which survived the First World War), publication of German language material was prohibited and schools attached to

In Australia, an official proclamation of 10 August 1914 required all German citizens to register their domiciles at the nearest police station and to notify authorities of any change of address. Under the later Aliens Restriction Order of 27 May 1915, enemy aliens who had not been interned had to report to the police once a week and could only change address with official permission. An amendment to the Restriction Order in July 1915 prohibited enemy aliens and naturalized subjects from changing their name or the name of any business they ran. Under the War Precautions Act of 1914 (which survived the First World War), publication of German language material was prohibited and schools attached to Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

churches were forced to abandon German as the language of teaching or were closed by the authorities. German clubs and associations were also closed.

The original German names of settlements and streets were officially changed. In South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, ''Grunthal'' became ''Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

'' and ''Krichauff'' became ''Beatty''. In New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

''Germantown'' became ''Holbrook Holbrook may refer to:

Places

England

*Holbrook, Derbyshire, a village

* Holbrook, Somerset, a hamlet in Charlton Musgrove

* Holbrook, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, a former mining village in Mosborough ward, now known as Halfway

*Holbrook, Suffolk, ...

'' after the submarine commander Norman Douglas Holbrook. This pressure was strongest in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

where 69 towns changed their names, including Petersburg, South Australia, which became Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

(see Australian place names changed from German names

During World War I, many German or German-sounding place names in Australia were changed due to anti-German sentiment. The presence of German-derived place names was seen as an affront to the war effort at the time.

The names were often change ...

).

Most of the anti-German feeling was created by the press that tried to create the idea that all those of German birth or descent supported Germany uncritically. This is despite many Germans and offspring such as Gen. John Monash

General (Australia), General Sir John Monash, (; 27 June 1865 – 8 October 1931) was an Australian civil engineer and military commander of the First World War. He commanded the 13th Brigade (Australia), 13th Infantry Brigade before the war an ...

serving Australia capably and honorably. A booklet circulated widely in 1915 claimed that "there were over 3,000 German spies scattered throughout the states". Anti-German propaganda was also inspired by several local and foreign companies who were keen to take the opportunity to eliminate Germany as a competitor in the Australian market. Germans in Australia were increasingly portrayed as evil by the very nature of their origins.

United States

After the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram partly sparked the American declaration of war against Imperial Germany in April 1917, German Americans were sometimes accused of being too sympathetic to Germany. Former president

After the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram partly sparked the American declaration of war against Imperial Germany in April 1917, German Americans were sometimes accused of being too sympathetic to Germany. Former president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

denounced " hyphenated Americanism", insisting that dual loyalties were impossible in wartime. A small minority of Americans, usually of German-American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

descent, came out for Germany. Similarly, Harvard psychology professor Hugo Münsterberg dropped his efforts to mediate between America and Germany, and threw his efforts behind the German cause.

The Justice Department attempted to prepare a list of all German aliens, counting approximately 480,000 of them, more than 4,000 of whom were imprisoned in 1917–18. The allegations included spying for Germany, or endorsing the German war effort. Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty. The Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

barred individuals with German last names from joining in fear of sabotage. One person was killed by a mob; in Collinsville, Illinois

Collinsville is a city located mainly in Madison County, and partially in St. Clair County, Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 25,579, an increase from 24,707 in 2000. Collinsville is approximately from St. Louis, Mi ...

, German-born Robert Prager was dragged from jail as a suspected spy and lynched.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, some German Americans were looked upon with suspicion and attacked regarding their loyalty. Some aliens were convicted and imprisoned on charges of sedition, for refusing to swear allegiance to the United States war effort.

In

When the United States entered the war in 1917, some German Americans were looked upon with suspicion and attacked regarding their loyalty. Some aliens were convicted and imprisoned on charges of sedition, for refusing to swear allegiance to the United States war effort.

In Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Frederick Stock

Frederick Stock (born Friedrich August Stock; November 11, 1872 – October 20, 1942) was a German conductor and composer, most famous for his 37-year tenure as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Early life and education

Born ...

was forced to step down as conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenu ...

until he finalized his naturalization papers. Orchestras replaced music by German composer Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

with French composer Berlioz.

In Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

, Luke Lea, the publisher of ''The Tennessean

''The Tennessean'' (known until 1972 as ''The Nashville Tennessean'') is a daily newspaper in Nashville, Tennessee. Its circulation area covers 39 counties in Middle Tennessee and eight counties in southern Kentucky. It is owned by Gannett, ...

'', together with "political associates", "conspired unsuccessfully to have the German-born Major Stahlman declared an "alien enemy" after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

began." Stahlman was the publisher of a competing newspaper, the '' Nashville Banner''.

The town, Berlin, Michigan, was renamed Marne, Michigan (in honor of those who fought in the Battle of the Marne). The town of Berlin, Shelby County Ohio changed its name to its original name of Fort Loramie, Ohio

Fort Loramie is a village in Shelby County, Ohio, United States, along Loramie Creek, a tributary of the Great Miami River in southwestern Ohio. It is 42 mi. northnorthwest of Dayton and 20 mi. east of the Ohio/Indiana border. The po ...

. The city of Germantown Germantown or German Town may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Germantown, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

United States

* Germantown, California, the former name of Artois, a census-designated place in Glenn County

* Ge ...

in Shelby County Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

temporarily changed its name to Neshoba during the war.

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, the offices of a pro-German, Socialist newspaper, the Philadelphia Tageblatt, were visited by federal agents after war broke out to investigate the citizenship status of its staff and would later be raided by federal agents under the powers of the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

, and six members of its organization would eventually be arrested for violations of the Espionage Act among other charges after publishing a number of pieces of pro-German propaganda.

German street names in many cities were changed. German and Berlin streets in Cincinnati became English and Woodward.Kathleen Doane"Anti-German hysteria swept Cincinnati in 1917"

. ''The Cincinnati Enquirer'', 6 June 2012. Accessed 15 February 2013. In Chicago Lubeck, Frankfort, and Hamburg Streets were renamed Dickens, Charleston, and Shakespeare Streets.Jack Simpson

"German Street Name Changes in Bucktown, Part I"

Newberry Library. In New Orleans, Berlin Street was renamed in honor of General Pershing, head of the American Expeditionary Force. In Indianapolis, Bismarck Avenue and Germania Street were renamed Pershing Avenue and Belleview Street, respectively in 1917, Brooklyn’s Hamburg Avenue was renamed Wilson Avenue. Many businesses changed their names. In Chicago, German Hospital became Grant Hospital; likewise the German Dispensary and the German Hospital in New York City were renamed

Lenox Hill Hospital

Lenox Hill Hospital (LHH) is a nationally ranked 450-bed non-profit, tertiary, research and academic medical center located on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City, servicing the tri-state area. LHH is one of the region's many unive ...

and Wyckoff Heights Hospital

Wyckoff Heights Medical Center is a 350-bed teaching hospital located in the Wyckoff Heights section of Bushwick, Brooklyn in New York City. The hospital is an academic affiliate of the NewYork-Presbyterian's Weill Cornell Medical College of Cor ...

respectively. In New York, the giant Germania Life Insurance Company became Guardian. At the US Customs House in Lower Manhattan, the word "Germany" which was on a shield that one of the building’s many figures was holding was chiseled over.

Many schools stopped teaching German-language classes. The City College of New York continued to teach German courses, but reduced the number of credits that students could receive for them. Books published in German were removed from libraries or even burned. In Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, the public library was asked to withdraw all German books from its shelves. In Iowa, in the 1918 Babel Proclamation, the governor of Iowa

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, William L. Harding, prohibited the use of all foreign languages in schools and public places. Nebraska banned instruction in any language except English, but the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled that the ban was illegal in 1923 (''Meyer v. Nebraska

''Meyer v. Nebraska'', 262 U.S. 390 (1923), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that a 1919 Nebraska law restricting foreign-language education violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. ...

'').

Some words of German origin were changed, at least temporarily. Sauerkraut

Sauerkraut (; , "sour cabbage") is finely cut raw cabbage that has been fermented by various lactic acid bacteria. It has a long shelf life and a distinctive sour flavor, both of which result from the lactic acid formed when the bacteria ferm ...

came to be called "liberty cabbage", German measles

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and ...

became "liberty measles", hamburger

A hamburger, or simply burger, is a food consisting of fillings—usually a patty of ground meat, typically beef—placed inside a sliced bun or bread roll. Hamburgers are often served with cheese, lettuce, tomato, onion, pickles, bacon, ...

s became "liberty sandwiches" and dachshunds became "liberty pups".

In parallel with these changes, many German Americans

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

elected to anglicize

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

their names (e.g. Schmidt to Smith, Müller to Miller) and limit the use of the German language in public places, especially in churches.

Ethnic German Medal of Honor winners were American USAAS ace pilots Edward Rickenbacker and Frank Luke

Frank Luke Jr. (May 19, 1897 – September 29, 1918) was an American fighter ace credited with 19 aerial victories, ranking him second among United States Army Air Service pilots after Captain Eddie Rickenbacker during World War I. Luke was t ...

; German-ethnicity DSC winners who also served with the USAAS in Europe included Joseph Frank Wehner

Joseph Frank Wehner (20 September 1895 – 18 September 1918), also known as Fritz Wehner, was an American fighter pilot and wingman to Frank Luke.

Early life

Wehner was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts on 20 September 1895. Wehner's athletic ...

and Karl John Schoen.

Second World War

United Kingdom

In 1940, the Ministry of Information launched an "Anger Campaign" to instill "personal anger ... against the German people and Germany", because the British were "harbouring little sense of real personal animus against the average German". This was done to strengthen British resolve against the Germans. Sir Robert Vansittart, the Foreign Office's chief diplomatic advisor until 1941, gave a series of radio broadcasts in which he said that Germany was a nation raised on "envy, self-pity and cruelty" whose historical development had "prepared the ground for Nazism" and that it wasNazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

that had "finally given expression to the blackness of the German soul".

The British Institute of Public Opinion (BIPO) tracked the evolution of anti-German/anti-Nazi feeling in Britain, asking the public, via a series of opinion polls conducted from 1939 to 1943, whether "the chief enemy of Britain was the German people or the Nazi government". In 1939, only 6% of respondents held the German people responsible; however, following the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

and the "Anger Campaign" in 1940, this increased to 50%. This subsequently declined to 41% by 1943. It also was reported by Home Intelligence in 1942 that there was some criticism of the official attitude of hatred towards Germany on the grounds that such hatred might hinder the possibility of a reasonable settlement following the war.

This attitude was expanded upon by J.R.R. Tolkien. In 1944, he wrote in a letter to his son Christopher:

is distressing to see the press grovelling in the gutter as low as Goebbels in his prime, shrieking that any German commander who holds out in a desperate situation (when, too, the military needs of his side clearly benefit) is a drunkard, and a besotted fanatic. ... There was a solemn article in the local paper seriously advocating systematic exterminating of the entire German nation as the only proper course after military victory: because, if you please, they are rattlesnakes, and don't know the difference between good and evil! (What of the writer?) The Germans have just as much right to declare theIn the same yearPoles Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...and Jews exterminable vermin,subhuman ''SubHuman'' is the sixth studio album by Recoil. Alan Wilder stated in a YouTube greeting that there would be a new album coming in spring or early summer 2007. On 23 April 2007, he released information regarding the album via Myspace and hi ..., as we have to select the Germans: in other words, no right, whatever they have done.

Mass Observation

Mass-Observation is a United Kingdom social research project; originally the name of an organisation which ran from 1937 to the mid-1960s, and was revived in 1981 at the University of Sussex.

Mass-Observation originally aimed to record everyday ...

asked its observers to analyse the British people's private opinions of the German people and it found that 54% of the British population was "pro-German", in that it expressed sympathy for the German people and stated that the war was "not their fault". This tolerance of the German people as opposed to the Nazi regime increased as the war progressed. In 1943, Mass Observation established the fact that up to 60% of the British people maintained a distinction between Germans and Nazis, with only 20% or so expressing any "hatred, vindictiveness, or need for retribution". The British film propaganda of the period similarly maintained the division between Nazi supporters and the German people.

United States in World War II

Between 1931 and 1940, 114,000 Germans and thousands of Austrians moved to the United States, many of whomincluding, e.g., Nobel prize winnerAlbert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Lion Feuchtwanger

Lion Feuchtwanger (; 7 July 1884 – 21 December 1958) was a German Jewish novelist and playwright. A prominent figure in the literary world of Weimar Germany, he influenced contemporaries including playwright Bertolt Brecht.

Feuchtwanger's J ...

, Bertold Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a p ...

, Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, Arnold Schönberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, Hanns Eisler

Hanns Eisler (6 July 1898 – 6 September 1962) was an Austrian composer (his father was Austrian, and Eisler fought in a Hungarian regiment in World War I). He is best known for composing the national anthem of East Germany, for his long artisti ...

and Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

were either Jewish Germans

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish ...

or anti-Nazis who were fleeing Nazi oppression. About 25,000 people became paying members of the pro-Nazi German American Bund

The German American Bund, or the German American Federation (german: Amerikadeutscher Bund; Amerikadeutscher Volksbund, AV), was a German-American Nazi organization which was established in 1936 as a successor to the Friends of New Germany (FoN ...

during the years before the war. The Alien Registration Act of 1940

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of ...

required 300,000 German-born resident aliens who had German citizenship to register with the Federal government and restricted their travel and property ownership rights. Under the still active Alien Enemy Act of 1798, the United States government interned nearly 11,000 German citizens between 1940 and 1948. An unknown number of "voluntary internees" joined their spouses and parents in the camps and were not permitted to leave. With the war ongoing in Europe but the U.S. neutral, a massive defense buildup took place, requiring many new hires. Private companies sometimes refused to hire any non-citizen, or American citizens of German or Italian ancestry. This threatened the morale of loyal Americans. President Franklin Roosevelt considered this "stupid" and "unjust". In June 1941, he issued Executive Order 8802

Executive Order 8802 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, to prohibit ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation's defense industry. It also set up the Fair Employment Practice Committee. It was the first federal ac ...

and set up the Fair Employment Practice Committee

The Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) was created in 1941 in the United States to implement Executive Order 8802 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt "banning discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies and all unions and com ...

, which also protected Black Americans.

President Roosevelt sought out Americans of German ancestry for top war jobs, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, and General Carl Andrew Spaatz. He appointed Republican Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 Republican nominee for President. Willkie appealed to many convention delegates as the Republican ...

as a personal representative. German Americans who had fluent German language skills were an important asset to wartime intelligence, and they served as translators and as spies for the United States. The war evoked strong pro-American patriotic sentiments among German Americans, few of whom by then had contacts with distant relatives in the old country.

The October 1939 seizure by the German pocket battleship

The ''Deutschland'' class was a series of three ''Panzerschiffe'' (armored ships), a form of heavily armed cruiser, built by the ''Reichsmarine'' officially in accordance with restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. The ships of the cl ...

''Deutschland

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

'' of the US freighter SS ''City of Flint'', as it had 4000 tons of oil for Britain on board, provoked much anti-German sentiment in the US.

Following its entry into the War against Nazi Germany on 11 December 1941, the US Government interned a number of German and Italian citizens as enemy aliens. The exact number of German and Italian internees is a subject of debate. In some cases their American-born family members volunteered to accompany them to internment camps in order to keep the family unit together. The last to be released remained in custody until 1948.

In 1944, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr. put forward the strongest proposal for punishing Germany to the Second Quebec Conference

Princess Alice, and Clementine Churchill">Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone">Princess Alice, and Clementine Churchill during the conference.

The Second Quebec Conference (codenamed "OCTAGON") was a high-level military conference held during ...

. It became known as the Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan was a proposal to eliminate Germany following World War II and eliminating its arms industry and removing or destroying other key industries basic to military strength. This included the removal or destruction of all industr ...

, and was intended to prevent Germany from having the industrial base to start another world war. However this plan was shelved quickly, the Western Allies did not seek reparations for war damage, and the United States implemented the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

that was intended to and did help West Germany's post war recovery to its former position as a pre-eminent industrial nation.

Brazil

After Brazil's entry into the war on the Allied side in 1942, anti-German riots broke out in nearly every city in Brazil in which Germans were not the majority population. German factories, including the Suerdieck cigar factory inBahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro) and the 5th-largest b ...

, shops, and hotels were destroyed by mobs. The largest demonstrations took place in Porto Alegre

Porto Alegre (, , Brazilian ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. Its population of 1,488,252 inhabitants (2020) makes it the twelfth most populous city in the country and the center of Brazil's fif ...

in Rio Grande do Sul. Brazilian police persecuted and interned "subjects of the Axis powers" in internment camps similar to those used by the US to intern Japanese-Americans. Following the war, German schools were not reopened, the German-language press disappeared completely, and use of the German language became restricted to the home and the older generation of immigrants.

Canada

There was also anti-German sentiment in Canada duringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Under the War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could t ...

, some 26 POW camps opened and were filled with those who had been born in Germany, Italy, and particularly in Japan, if they were deemed to be "enemy aliens". For Germans, this applied especially to single males who had some association with the Nazi Party of Canada. No compensation was paid to them after the war. In Ontario, the largest internment centre for German Canadians was at Camp Petawawa, housing 750 who had been born in Germany and Austria. Although some residents of internment camps were Germans who had already immigrated to Canada, the majority of Germans in such camps were from Europe; most were prisoners of war.

Soviet Union

On 25 July 1937, NKVD Order No. 00439 led to the arrest of 55,005 German citizens and former citizens in theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, of whom 41,898 were sentenced to death."Foreigners in GULAG: Soviet Repressions of Foreign Citizens"by

Pavel Polian

Pavel Markovich Polian, pseudonym: Pavel Nerler (russian: Павел Маркович Полян; born 31 August 1952) is a Russian geographer and historian, and Doctor of Geographical Sciences with the Institute of Geography (1998) of the Russian ...

*English language version (shortened): P.Polian. Soviet Repression of Foreigners: The Great Terror, the GULAG, Deportations, Annali. Anno Trentasttesimo, 2001. Feltrinelli Editore Milano, 2003. – P.61-104

Later during the war Germans were suggested to be used for forced labour. The Soviet Union began deporting ethnic Germans in their territories and using them for forced labour. Although by the end of 1955, they had been acquitted of criminal accusations, no rights to return to their former home regions were granted, nor were the former self-determination rights returned to them.

Postwar

In state-sponsored genocides, millions of people were murdered by Germans during World War II. That turned families and friends of the victims anti-German. American GeneralGeorge S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

complained that the US policy of denazification following Germany's surrender harmed American interests and was motivated simply by hatred of the defeated German people. Even the speed of West German

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

recovery following the war was seen as ominous by some, who suspected the Germans of planning for World War III

World War III or the Third World War, often abbreviated as WWIII or WW3, are names given to a hypothetical worldwide large-scale military conflict subsequent to World War I and World War II. The term has been in use since at ...

. In reality, most Nazi criminals were unpunished, such as Heinz Reinefarth

Heinz Reinefarth (26 December 1903 – 7 May 1979) was a German SS commander during World War II and government official in West Germany after the war. During the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944 his troops committed numerous atrocities. After t ...

, who was responsible for the Wola massacre

The Wola massacre ( pl, Rzeź Woli, lit=Wola slaughter) was the systematic killing of between 40,000 and 50,000 Poles in the Wola neighbourhood of the Polish capital city, Warsaw, by the German Wehrmacht and fellow Axis collaborators in the ...

. Many Nazis worked for the Americans as scientists (Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

) or intelligence officers (Reinhard Gehlen

Reinhard Gehlen (3 April 1902 – 8 June 1979) was a German lieutenant-general and intelligence officer. He was chief of the Wehrmacht Foreign Armies East military intelligence service on the eastern front during World War II, spymaster of the ...

).

Nakam

Nakam was a group of about fifty Holocaust survivors that in 1945 sought to kill Germans and Nazis in revenge for the murder of six million Jews during the Holocaust.Flight and expulsion of Germans

After WWII ended, about 11 million to 12 millionJürgen Weber, Germany, 1945–1990: A Parallel History, Central European University Press, 2004, p.2, Peter H. Schuck, Rainer Münz, Paths to Inclusion: The Integration of Migrants in the United States and Germany, Berghahn Books, 1997, p.156, Germans fled or were expelled from Germany's former eastern provinces or migrated from other countries to what remained of Germany, the largesttransfer

Transfer may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Transfer'' (2010 film), a German science-fiction movie directed by Damir Lukacevic and starring Zana Marjanović

* ''Transfer'' (1966 film), a short film

* ''Transfer'' (journal), in management studies

...

of a single European population in modern history.Arie Marcelo Kacowicz, Pawel Lutomski, Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study, Lexington Books, 2007, p.100, : "... largest movement of European people in modern history/ref> Estimates of the total number of dead range from 500,000 to 2,000,000, and the higher figures include "unsolved cases" of persons reported missing and presumed dead. Many German civilians were sent to internment and labor camps, where they died.

Salomon Morel

Salomon Morel (November 15, 1919 – February 14, 2007) was an officer in the Ministry of Public Security in the Polish People's Republic. Morel was a commander of concentration camps run by the NKVD and communist authorities until 1956.

Aft ...

and Czesław Gęborski Czesław Gęborski (; 5 June 1924, Dąbrowa Górnicza – 14 June 2006) was a captain of the security forces of the People's Republic of Poland. He is best known for his role as commander of the Łambinowice transfer and internment camp created ...

were the commanders of several camps for Germans, Poles and Ukrainians. The German-Czech Historians Commission, on the other hand, established a death toll for Czechoslovakia of 15,000–30,000. The events are usually classified as population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is ...

, or ethnic cleansing.

Felix Ermacora

Felix Ermacora (13 October 1923 – 24 February 1995) was a leading human rights expert of Austria and a member of the Austrian People's Party.

Biography

In his youth, Ermacora served in the army of Nazi Germany at the rank of private.

He wa ...

was one a minority of legal scholars to equate ethnic cleansing with genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

, and stated that the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans was therefore genocide.

Forced labor of Germans

During the Allied occupation of Germany, Germans were used as forced laborers after 1945. Some of the laborers, depending on the country occupying, were prisoners of war or ethnic German civilians.In Israel

In the 21st century, the long debate about whether theIsrael Philharmonic Orchestra

The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (abbreviation IPO; Hebrew: התזמורת הפילהרמונית הישראלית, ''ha-Tizmoret ha-Filharmonit ha-Yisra'elit'') is an Israeli symphony orchestra based in Tel Aviv. Its principal concert venue ...

should play the works of Richard Wagner is mostly considered as a remnant of the past. In March 2008, German Chancellor Angela Merkel

Angela Dorothea Merkel (; ; born 17 July 1954) is a German former politician and scientist who served as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), she previously served as Leader of the Opp ...

became the first foreign head of government invited to deliver a speech in the Israeli parliament, which she gave in German. Several members of parliament left in protest during the speech and claimed the need to create a collective memory

Collective memory refers to the shared pool of memories, knowledge and information of a social group that is significantly associated with the group's identity. The English phrase "collective memory" and the equivalent French phrase "la mémoire c ...