Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

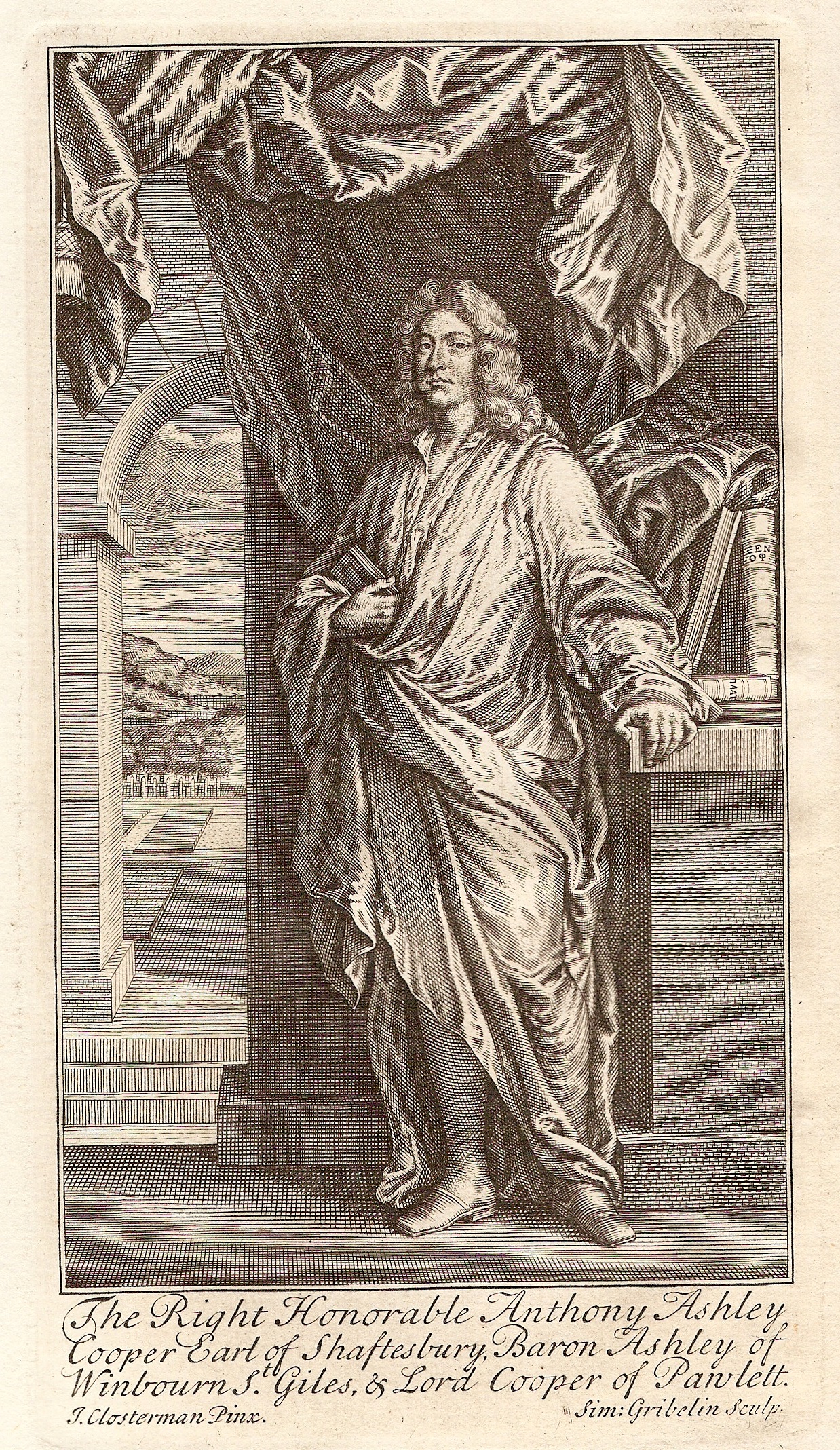

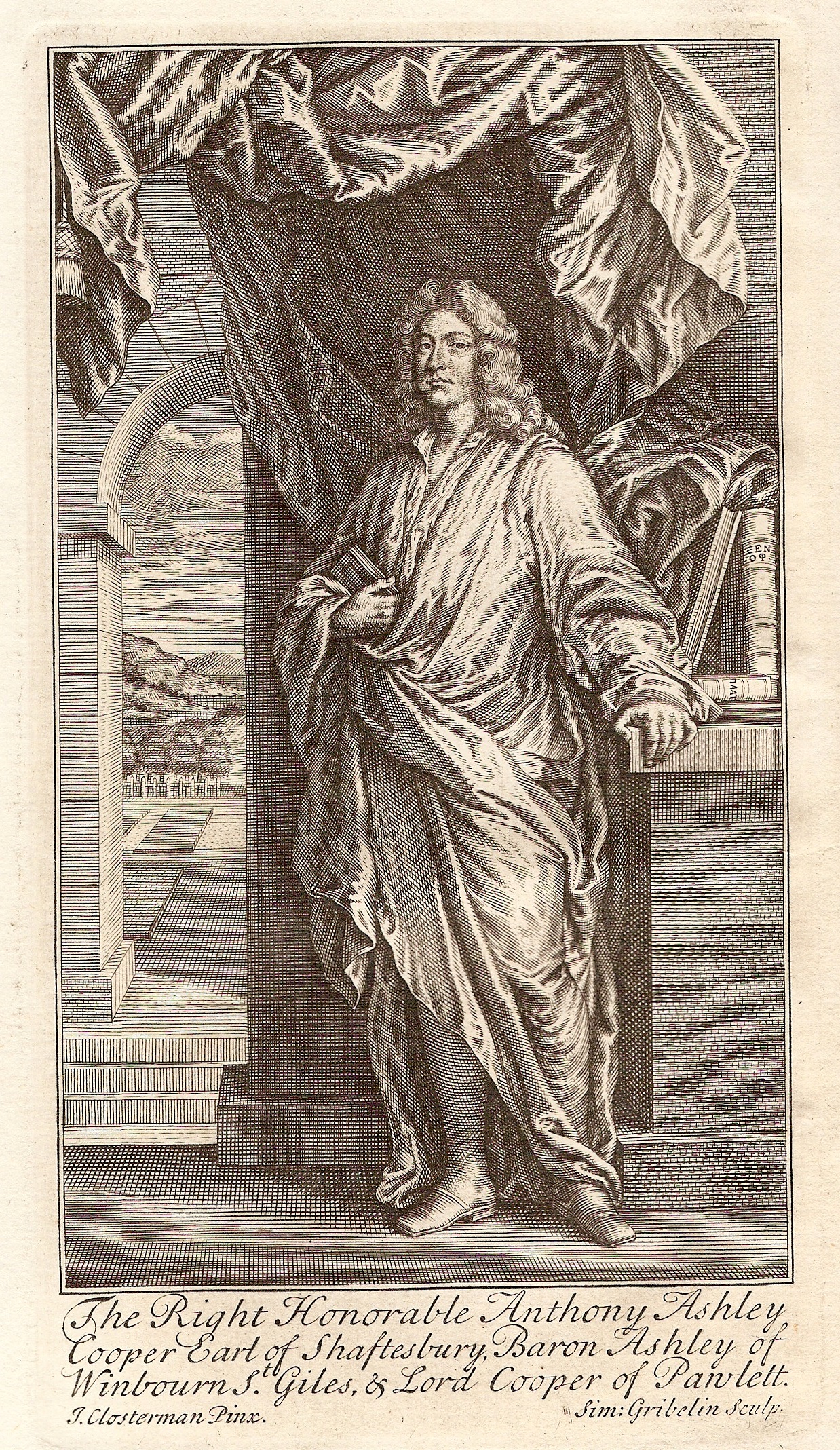

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (26 February 1671 – 16 February 1713) was an

Shaftesbury as a moralist opposed

Shaftesbury as a moralist opposed

"Or that bright Image to our Fancy draw,

Which Theocles in raptur'd vision saw,

While thro' Poetic scenes the Genius roves,

Or wanders wild in Academic Groves".

In notes to these lines, Pope directed the reader to various passages in Shaftesbury's work.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Shaftesbury built a

At the beginning of the 18th century, Shaftesbury built a

Shaftesbury's ''Characteristicks'' in three parts

Contains the five treatises in Shaftesbury's ''Characteristicks'', slightly modified for easier reading

''The Third Earl of Shaftesbury''

an article by John McAteer in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2011 {{DEFAULTSORT:Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl Of 1671 births 1713 deaths 17th-century English philosophers 18th-century essayists 18th-century British philosophers Age of Enlightenment

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking ...

, philosopher, and writer

A writer is a person who uses written words in different writing styles and techniques to communicate ideas. Writers produce different forms of literary art and creative writing such as novels, short stories, books, poetry, travelogues, p ...

.

Early life

He was born at Exeter House in London, the son of the future Anthony Ashley Cooper, 2nd Earl of Shaftesbury and his wife Lady Dorothy Manners, daughter ofJohn Manners, 8th Earl of Rutland

John Manners, 8th Earl of Rutland (10 June 160429 September 1679), was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640 until 1641 when he inherited the title Earl of Rutland on the death of his second cousin George Manners, 7t ...

. Letters sent to his parents reveal emotional manipulation

Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is currently no scientific consensus on a definitio ...

attempted by his mother in refusing to see her son unless he cut off all ties to his father. At the age of three Ashley-Cooper was made over to the formal guardianship of his grandfather Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury PC FRS (22 July 1621 – 21 January 1683; known as Anthony Ashley Cooper from 1621 to 1630, as Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper, 2nd Baronet from 1630 to 1661, and as The Lord Ashley from 1661 to 1 ...

. John Locke, as medical attendant to the Ashley household, was entrusted with the supervision of his education. It was conducted according to the principles of Locke's '' Some Thoughts Concerning Education'' (1693), and the method of teaching Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

conversationally was pursued by his instructress, Elizabeth Birch. At the age of eleven, it is said, Ashley could read both languages with ease. Birch had moved to Clapham and Ashley spent some years there with her.

In 1683, after the death of the first Earl, his father sent Lord Ashley, as he now was by courtesy, to Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

. From a prominent Whig background, in a Tory institution, he was unhappy there. Around 1686 he was withdrawn. Under a Scottish tutor, Daniel Denoune, he began a continental tour with two older companions, Sir John Cropley, 2nd Baronet

Sir John Cropley, 2nd Baronet (15 July 1663 – 22 October 1713), of Red Lion Square, was an English Whig politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons from 1701 to 1710.

Early life

Cropley was baptised at St. James Clerkenw ...

, and Thomas Sclater Bacon.

Under William and Mary

After the Glorious Revolution, Lord Ashley returned to England in 1689. It took five years, but he entered public life, as a parliamentary candidate for the borough of Poole, and was returned on 21 May 1695. He spoke for the Bill for Regulating Trials in Cases of Treason, one provision of which was that a person indicted fortreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

or misprision of treason

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a p ...

should be allowed the assistance of counsel.

Although a Whig, Ashley was not partisan. His poor health forced him to retire from parliament at the dissolution of July 1698. He suffered from asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, co ...

. The following year, to escape the London environment, he purchased a property in Little Chelsea, adding a 50-foot extension to the existing building to house his bedchamber and Library, and planting fruit trees and vines. He sold the property to Narcissus Luttrell

Narcissus Luttrell (1657–1732) was an English historian, diarist, and bibliographer, and briefly Member of Parliament for two different Cornish boroughs. His ''Brief Historical Relation of State Affairs from September 1678 to April 1714'', a c ...

in 1710.

Lord Ashley moved to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. Away for over a year, Ashley returned to England, and shortly succeeded his father as Earl of Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his fa ...

. He took an active part, on the Whig side in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

, in the general election of 1700–1701, and again, with more success, in the autumn election of 1701.

Under Queen Anne

After the first few weeks ofAnne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

's reign, Shaftesbury, who had been deprived of the vice-admiralty of Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, returned to private life. In August 1703, he again settled in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. At Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"Ne ...

he lived, he says in a letter to his steward Wheelock, at the rate of less than £200 a year, and yet had much to dispose of and spend beyond convenient living.

Shaftesbury returned to England in August 1704, he landed at Aldeburgh

Aldeburgh ( ) is a coastal town in the county of Suffolk, England. Located to the north of the River Alde. Its estimated population was 2,276 in 2019. It was home to the composer Benjamin Britten and remains the centre of the international Alde ...

, Suffolk having escaped a dangerous storm during his voyage. He had symptoms of consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

, and gradually became an invalid. He continued to take an interest in politics, both home and foreign, and supported England's participation in the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

.

The declining state of Shaftesbury's health rendered it necessary for him to seek a warmer climate and in July 1711 he set out for Italy. He settled at Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

in November, and lived there for more than a year.

Death

Shaftesbury died at Chiaia in the Kingdom of Naples, on 15 February 1713 (N.S.) His body was brought back to England and buried at Wimborne St Giles, the family seat in Dorset.Associations

John Toland

John Toland (30 November 167011 March 1722) was an Irish rationalist philosopher and freethinker, and occasional satirist, who wrote numerous books and pamphlets on political philosophy and philosophy of religion, which are early expressions o ...

was an early associate, but Shaftesbury after some time found him a troublesome ally. Toland published a draft of the ''Inquiry concerning Virtue'', without permission. Shaftesbury may have exaggerated its faults, but the relationship cooled. Toland edited 14 letters from Shaftesbury to Robert Molesworth, published in Toland in 1721. Molesworth had been a good friend from the 1690s. Other friends among English Whigs were Charles Davenant

Charles Davenant (1656–1714) was an English mercantilist economist, politician, and pamphleteer. He was Tory member of Parliament for St Ives (Cornwall), and for Great Bedwyn.

Life

He was born in London as the eldest son of Sir William Davena ...

, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, Walter Moyle, William Stephens and John Trenchard.

From Locke's circle in England, Shaftesbury knew Edward Clarke, Damaris Masham and Walter Yonge. In the Netherlands in the late 1690s, he got to know Locke's contact Benjamin Furly

Benjamin Furly (13 April 1636 – March 1714) was an English Quaker merchant and friend of John Locke.

Life

Furly was born at Colchester 13 April 1636, began life as a merchant there, and joined the early Quakers. In 1659–60 he assisted John ...

. Through Furly he had introductions to become acquainted with Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. A Huguenot, Bayle fled to the Dutch Republic in 1681 because of religious persecution in France. He is best known for his '' Histori ...

, Jean Leclerc and Philipp van Limborch

Philipp van Limborch (19 June 1633 – 30 April 1712) was a Dutch Remonstrant theologian.

Biography

Limborch was born on 19 June 1633 in Amsterdam, where his father was a lawyer. He received his education at Utrecht, at Leiden, in his native cit ...

. Bayle introduced him to Pierre Des Maizeaux

Pierre des Maizeaux, also spelled Desmaizeaux (c. 1666 or 1673June 1745), was a French Huguenot writer exiled in London, best known as the translator and biographer of Pierre Bayle.

He was born in Pailhat, Auvergne, France. His father, a minister ...

. Letters from Shaftesbury to Benjamin Furly, his two sons, and his clerk Harry Wilkinson, were included in a volume entitled ''Original Letters of Locke, Sidney and Shaftesbury'', published by Thomas Ignatius Maria Forster (1830, and in enlarged form, 1847).

Shaftesbury was a patron of Michael Ainsworth, a young Dorset man of Wimborne St Giles, maintained by Shaftesbury at University College, Oxford

University College (in full The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, colloquially referred to as "Univ") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It has a claim to being the oldest college of the unive ...

. The ''Letters to a Young Man at the University'' (1716) were addressed to Ainsworth. Others he supported included Pierre Coste and Paul Crellius.

Works

Most of the works for which Shaftesbury is known were completed in the period 1705 to 1710. He collected a number of those and other works in ''Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times'' (first edition 1711, anonymous, 3 vols.). His philosophical work was limited to ethics, religion, and aesthetics where he highlighted the concept of the sublime as an aesthetic quality. Basil Willey wrote " ..his writings, though suave and polished, lack distinction of style ...Contents of the ''Characteristicks''

This listing refers to the first edition. The later editions saw changes. The ''Letter on Design'' was first published in the edition of the ''Characteristicks'' issued in 1732. ;Volume I The opening piece is ''A Letter Concerning Enthusiasm'', advocatingreligious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

, published anonymously in 1708. It was based on a letter sent to John Somers, 1st Baron Somers

John Somers, 1st Baron Somers, (4 March 1651 – 26 April 1716) was an English Whig jurist and statesman. Somers first came to national attention in the trial of the Seven Bishops where he was on their defence counsel. He published tracts on ...

of September 1707. At this time repression of the French Camisards was topical. The second treatise is ''Sensus Communis: An Essay on the Freedom of Wit and Humour'', first published in 1709. The third part is ''Soliloquy: or, Advice to an Author'', from 1710.

;Volume II

It opens with ''Inquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit'', based on a work from 1699. With this treatise, Shaftesbury became the founder of moral sense theory Moral sense theory (also known as moral sentimentalism) is a theory in moral epistemology and meta-ethics concerning the discovery of moral truths. Moral sense theory typically holds that distinctions between morality and immorality are discovered ...

. It is accompanied by ''The Moralists, a Philosophical Rhapsody'', from 1709. Shaftesbury himself regarded it as the most ambitious of his treatises. The main object of ''The Moralists'' is to propound a system of natural theology, for theodicy

Theodicy () means vindication of God. It is to answer the question of why a good God permits the manifestation of evil, thus resolving the issue of the problem of evil. Some theodicies also address the problem of evil "to make the existence of ...

. Shaftesbury believed in one God whose characteristic attribute is universal benevolence; in the moral government of the universe; and in a future state of man making up for the present life.

;Volume III

Entitled ''Miscellaneous Reflections'', this consisted of previously unpublished works. From his stay at Naples there was ''A Notion of the Historical Draught or Tablature of the Judgment of Hercules''.

Philosophical moralist

Shaftesbury as a moralist opposed

Shaftesbury as a moralist opposed Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

. He was a follower of the Cambridge Platonists

The Cambridge Platonists were an influential group of Platonist philosophers and Christian theologians at the University of Cambridge that existed during the 17th century. The leading figures were Ralph Cudworth and Henry More.

Group and its na ...

, and like them rejected the way Hobbes collapsed moral issues into expediency. His first published work was an anonymous ''Preface'' to the sermons of Benjamin Whichcote, a prominent Cambridge Platonist, published in 1698. In it he belaboured Hobbes and his ethical egoism, but also the commonplace carrot and stick

The phrase "carrot and stick" is a metaphor for the use of a combination of reward and punishment to induce a desired behaviour.

In politics, "carrot or stick" sometimes refers to the realist concept of soft and hard power. The carrot in this ...

arguments of Christian moralists. While Shaftesbury conformed in public to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, his private view of some its doctrines was less respectful.

His starting point in the ''Characteristicks'', however, was indeed such a form of ethical naturalism

Ethical naturalism (also called moral naturalism or naturalistic cognitivistic definism) is the meta-ethical view which claims that:

# Ethical sentences express propositions.

# Some such propositions are true.

# Those propositions are made true ...

as was common ground for Hobbes, Bernard Mandeville and Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

: appeal to self-interest. He divided moralists into Stoics and Epicurean, identifying with the Stoics and their attention to the common good

In philosophy, economics, and political science, the common good (also commonwealth, general welfare, or public benefit) is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, or alternatively, what is achieved by c ...

. It made him concentrate on virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standards ...

. He took Spinoza and Descartes as the leading Epicureans of his time (in unpublished writings).

Shaftesbury examined man first as a unit in himself, and secondly socially. His major principle was harmony or balance, rather than rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

. In man, he wrote,

"Whoever is in the least versed in this moral kind of architecture will find the inward fabric so adjusted, ..that the barely extending of a single passion too far or the continuance ..of it too long, is able to bring irrecoverable ruin and misery".This version of a golden mean doctrine that goes back to

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

was savaged by Mandeville, who slurred it as associated with a sheltered and comfortable life, Catholic asceticism, and modern sentimental rusticity. On the other hand, Jonathan Edwards adopted Shaftesbury's view that "all excellency is harmony, symmetry or proportion".

On man as a social creature, Shaftesbury argued that the egoist and the extreme altruist

Altruism is the principle and moral practice of concern for the welfare and/or happiness of other human beings or animals, resulting in a quality of life both material and spiritual. It is a traditional virtue in many cultures and a core as ...

are both imperfect. People, to contribute to the happiness of the whole, must fit in. He rejected the idea that humankind is naturally selfish; and the idea that altruism necessarily cuts across self-interest. Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

found this general and social approach attractive.

This move relied on a close parallel between moral and aesthetic criteria. In the English tradition, this appeal to a moral sense was innovative. Primarily emotional and non-reflective, it becomes rationalised by education and use. Corollaries are that morality stands apart from theology, and the moral qualities of actions are determined apart from the will of God

The will of God or divine will is a concept found in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament and the Quran, according to which God's will is the first cause of everything that exists.

See also

* Destiny

* ''Deus vult'', a Latin expression meaning ...

; and that the moralist is not concerned to solve the problems of free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

and determinism. Shaftesbury in this way opposed also what is to be found in Locke.

Reception

The conceptual framework used by Shaftesbury was representative of much thinking in the early Enlightenment, and remained popular until the 1770s. When the ''Characteristicks'' appeared they were welcomed by Le Clerc andGottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

. Among the English deists

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning " god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of ...

Shaftesbury was significant, plausible and the most respectable.

By the Augustans

In terms ofAugustan literature

Augustan literature (sometimes referred to misleadingly as Georgian literature) is a style of British literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II in the first half of the 18th century and ending in the 17 ...

, Shaftesbury's defence of ridicule

Mockery or mocking is the act of insulting or making light of a person or other thing, sometimes merely by taunting, but often by making a caricature, purporting to engage in imitation in a way that highlights unflattering characteristics. Mock ...

was taken as an entitlement to scoff, and to use ridicule as a "test of truth". Clerical authors operated on the assumption that he was a freethinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other metho ...

. Ezra Stiles, reading ''Characteristicks'' in 1748 without realising Shaftesbury had been marked down as a deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, was both impressed and sometimes shocked. Around this time John Leland and Philip Skelton stepped up a campaign against deist influence, tarnishing Shaftesbury's reputation.

While Shaftesbury wrote on ridicule in the 1712 edition of ''Characteristicks'', the modern scholarly consensus is that the uses of his views on it as a "test of truth" were a stretch. According to Alfred Owen Aldridge Alfred Owen Aldridge (December 16, 1915 – January 29, 2005) was a professor of French and comparative literature, founder-editor of the journal ''Comparative Literature Studies'', and author of books on a wide range of literature studies.

Car ...

, the "test of truth" phrase is not to be found in ''Characteristicks''; it was imposed on the Augustan debate by George Berkeley.

The influence of Shaftesbury, and in particular ''The Moralists'', on ''An Essay on Man

''An Essay on Man'' is a poem published by Alexander Pope in 1733–1734. It was dedicated to Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, (pronounced 'Bull-en-brook') hence the opening line: "Awake, St John...". It is an effort to rationalize or r ...

'', was claimed in the 18th century by Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

(in his philosophical letter "On Pope"), Lord Hervey and Thomas Warton

Thomas Warton (9 January 172821 May 1790) was an English literary historian, critic, and poet. He was appointed Poet Laureate in 1785, following the death of William Whitehead.

He is sometimes called ''Thomas Warton the younger'' to disti ...

, and supported in recent times, for example by Maynard Mack. Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

did not mention Shaftesbury explicitly as a source: this omission has been understood in terms of the political divide, Pope being a Tory. Pope references the character Theocles from ''The Moralists'' in the ''Dunciad

''The Dunciad'' is a landmark, mock-heroic, narrative poem by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times from 1728 to 1743. The poem celebrates a goddess Dulness and the progress of her chosen agents as they bring ...

'' (IV.487–490):

In moral philosophy and its literary reflection

Shaftesbury's ethical system was rationalised by Francis Hutcheson, and from him passed with modifications toDavid Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment phil ...

; these writers, however, changed from reliance on moral sense to the deontological ethics

In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek: + ) is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules and principles, ...

of moral obligation. From there it was taken up by Adam Smith, who elaborated a theory of moral judgement with some restricted emotional input, and a complex apparatus taking context into account. Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler (18 May O.S. 1692 – 16 June O.S. 1752) was an English Anglican bishop, theologian, apologist, and philosopher, born in Wantage in the English county of Berkshire (now in Oxfordshire). He is known for critiques of Deism, Thom ...

adopted the system, but not ruling out the place of " moral reason", a rationalist version of the affective moral sense. Samuel Johnson, the American educator, did not accept Shaftesbury's moral sense as a given, but believed it might be available by intermittent divine intervention.

In the English sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th-century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility. Sentimentalism, which is to be distinguished from sens ...

of the 18th century, arguments from the Shaftesbury–Hutcheson tradition appear. An early example in Mary Collyer's ''Felicia to Charlotte'' (vol.1, 1744) comes from its hero Lucius, who reasons in line with ''An Enquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit'' on the "moral sense". The second volume (1749) has discussions of conduct book

Conduct books or conduct literature is a genre of books that attempt to educate the reader on social norms and ideals. As a genre, they began in the mid-to-late Middle Ages, although antecedents such as ''The Maxims of Ptahhotep'' (c. 2350 BC) ...

material, and makes use of the ''Philemon to Hydaspes'' (1737) of Henry Coventry

Henry Coventry (1619–1686), styled "The Honourable" from 1628, was an English politician who was Secretary of State for the Northern Department between 1672 and 1674 and the Southern Department between 1674 and 1680.

Origins and education

Co ...

, described by Aldridge as "filled with favorable references to Shaftesbury." The eponymous hero of '' The History of Sir Charles Grandison'' (1753) by Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: ''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History of ...

has been described as embodying the "Shaftesburian model" of masculinity: he is "stoic, rational, in control, yet sympathetic towards others, particularly those less fortunate." ''A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy

''A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy'' is a novel by Laurence Sterne, written and first published in 1768, as Sterne was facing death. In 1765, Sterne travelled through France and Italy as far south as Naples, and after returning det ...

'' (1768) by Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768), was an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric who wrote the novels ''The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman'' and '' A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy'', publishe ...

was intended by its author to evoke the "sympathizing principle" on which the tradition founded by latitudinarian

Latitudinarians, or latitude men, were initially a group of 17th-century English theologiansclerics and academicsfrom the University of Cambridge who were moderate Anglicans (members of the Church of England). In particular, they believed that ...

s, Cambridge Platonists and Shaftesbury relied.

Across Europe

In 1745Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

adapted or reproduced the ''Inquiry concerning Virtue'' in what was afterwards known as his ''Essai sur le Mérite et la Vertu''. In 1769 a French translation of the whole of Shaftesbury's works, including the ''Letters'', was published at Geneva.

Translations of separate treatises into German began to be made in 1738, and in 1776–1779 there appeared a complete German translation of the ''Characteristicks''. Hermann Theodor Hettner stated that not only Leibniz, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

and Diderot, but Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or ' ...

, Christoph Martin Wieland and Johann Gottfried von Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, '' Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohrun ...

, drew from Shaftesbury.

Herder in early work took from Shaftesbury arguments for respecting individuality, and against system and universal psychology. He went on to praise him in ''Adrastea''. Wilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (, also , ; ; 22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a Prussian philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin, which was named afte ...

found in Shaftesbury the "inward form" concept, key for education in the approach of German classical philosophy. Later philosophical writers in German ( Gideon Spicker with ''Die Philosophie des Grafen von Shaftesbury'', 1872, and Georg von Gizycki with ''Die Philosophie Shaftesbury's'', 1876) returned to Shaftesbury in books.

Legacy

At the beginning of the 18th century, Shaftesbury built a

At the beginning of the 18th century, Shaftesbury built a folly

In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings.

Eighteenth-cent ...

on the Shaftesbury Estate, known as the Philosopher's Tower. It sits in a field, visible from the B3078 just south of Cranborne

Cranborne is a village in East Dorset, England. At the 2011 census, the parish had a population of 779, remaining unchanged from 2001.

The appropriate electoral ward is called 'Crane'. This ward includes Wimborne St. Giles in the west and so ...

.

In the Shaftesbury papers that went to the Public Record Office

The Public Record Office (abbreviated as PRO, pronounced as three letters and referred to as ''the'' PRO), Chancery Lane in the City of London, was the guardian of the national archives of the United Kingdom from 1838 until 2003, when it was ...

are several memoranda, letters, rough drafts, etc.

A portrait of the 3rd Earl is displayed in Shaftesbury Town Hall.

Family

Shaftesbury married in 1709 Jane Ewer, the daughter of Thomas Ewer of Bushey Hall, Hertfordshire. On 9 February 1711, their only child Anthony, the future fourth Earl was born. His son succeeded him in his titles and republished ''Characteristicks'' in 1732. His great-grandson was the famous philanthropist, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury.Notes

;Attribution *Further reading

* Cooper, Anthony Ashley, Earl of Shaftesbury, ''An Inquiry Concerning Virtue'', London, 1699. Facsimile ed., introd. Joseph Filonowicz, 1991, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, . * David Walford (editor). ''An Inquiry Concerning Virtue or Merit.'' A selection of material from Toland's 1699 edition with introduction. * Robert B. Voitle, ''The third Earl of Shaftesbury, 1671–1713'', Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, c. 1984. * Edward Chaney (2000), ''George Berkeley's Grand Tours: The Immaterialist as Connoisseur of Art and Architecture'', in E. Chaney, The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed. London, Routledge *External links

* *Shaftesbury's ''Characteristicks'' in three parts

Contains the five treatises in Shaftesbury's ''Characteristicks'', slightly modified for easier reading

''The Third Earl of Shaftesbury''

an article by John McAteer in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2011 {{DEFAULTSORT:Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl Of 1671 births 1713 deaths 17th-century English philosophers 18th-century essayists 18th-century British philosophers Age of Enlightenment

Anthony

Anthony or Antony is a masculine given name, derived from the '' Antonii'', a ''gens'' ( Roman family name) to which Mark Antony (''Marcus Antonius'') belonged. According to Plutarch, the Antonii gens were Heracleidae, being descendants of Anton, ...

British deists

British ethicists

British male essayists

Cambridge Platonists

3

English essayists

Ashley, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Lord

Enlightenment philosophers

Moral philosophers

Neoplatonists

People educated at Winchester College

Philosophers of ethics and morality

Philosophers of religion

Philosophers of social science