Angolan War of Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

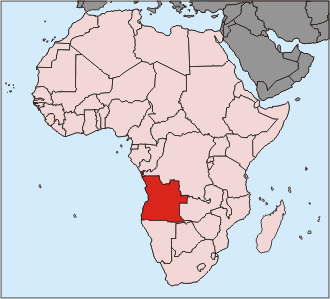

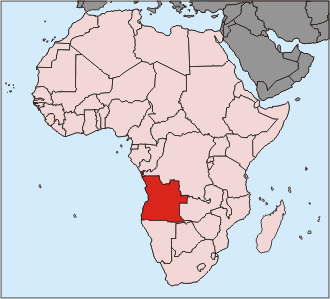

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal's overseas province of Angola among three

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal's overseas province of Angola among three

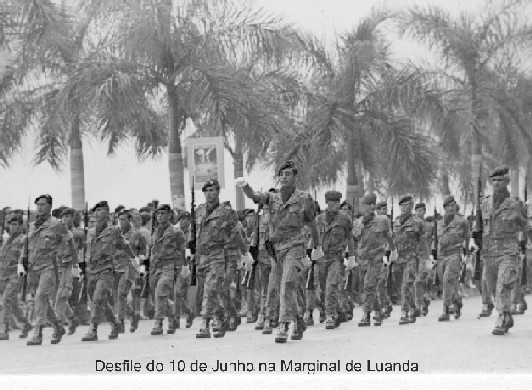

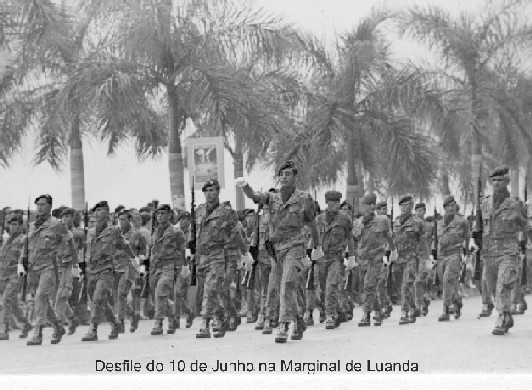

Angola 1966–74

/ref> Many atrocities were committed by all forces involved in the conflict. In the end, the Portuguese achieved overall military victory. In Angola, after the Portuguese withdrew, an armed conflict broke out among the nationalist movements. This war formally came to an end in January 1975 when the Portuguese government, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) signed the

The Portuguese forces engaged in the conflict included mainly the

The Portuguese forces engaged in the conflict included mainly the

The Portuguese air assets in Angola were under the command of the 2nd Air Region of the

The Portuguese air assets in Angola were under the command of the 2nd Air Region of the

The Portuguese Colonial Act – passed on 13 June 1933 – defined the relationship between the Portuguese overseas territories and the metropole, until being revised in 1951. The Colonial Act reflected an imperialistic view of the overseas territories typical among the European colonial powers of the late 1920s and 1930s. During the period in which it was in force, the Portuguese overseas territories lost the status of "provinces" that they have had since 1834, becoming designated "colonies", with the whole Portuguese overseas territories becoming officially designated " Portuguese Colonial Empire". The Colonial Act subtly recognized the supremacy of the Portuguese over native people, and even if the natives could pursue all studies including

The Portuguese Colonial Act – passed on 13 June 1933 – defined the relationship between the Portuguese overseas territories and the metropole, until being revised in 1951. The Colonial Act reflected an imperialistic view of the overseas territories typical among the European colonial powers of the late 1920s and 1930s. During the period in which it was in force, the Portuguese overseas territories lost the status of "provinces" that they have had since 1834, becoming designated "colonies", with the whole Portuguese overseas territories becoming officially designated " Portuguese Colonial Empire". The Colonial Act subtly recognized the supremacy of the Portuguese over native people, and even if the natives could pursue all studies including

"A Sublevação da Baixa do Cassange", ''Revista Militar'', 2011

/ref>

On 15 March 1961, the

On 15 March 1961, the

In 1973 Chipenda left the MPLA, founding the

In 1973 Chipenda left the MPLA, founding the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade Secretary of State

AFRICA-PORTUGAL: Three Decades After Last Colonial Empire Came to an End

A level of economic development comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule became a major goal for the governments of the independent territory. The sharp recession and the chaos in many areas of Angolan life eroded the initial impetus of nationalistic fervor. There were also eruptions of black racism in the former overseas province against white and mulatto Angolans."Things are going well in Angola. They achieved good progress in their first year of independence. There's been a lot of building and they are developing health facilities. In 1976 they produced 80,000 tons of coffee. Transportation means are also being developed. Currently between 200,000 and 400,000 tons of coffee are still in warehouses. In our talks with ngolan President AgostinhoNeto we stressed the absolute necessity of achieving a level of economic development comparable to what had existed under ortuguesecolonialism."; "There is also evidence of black racism in Angola. Some are using the hatred against the colonial masters for negative purposes. There are many mulattos and whites in Angola. Unfortunately, racist feelings are spreading very quickly.

Fidel Castro, Castro's 1977 southern Africa tour: A report to

Guerra Colonial: 1961–1974 – State-supported historical site of the Portuguese Colonial War (Portugal)

U.S. Involvement in Angolan Conflict

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archive

{{Authority control Portuguese Angola *Angolan

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal's overseas province of Angola among three

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal's overseas province of Angola among three nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

movements and a separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

movement. The war ended when a leftist military coup in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

in April 1974 overthrew Portugal's '' Estado Novo'' dictatorship, and the new regime immediately stopped all military action in the African colonies, declaring its intention to grant them independence without delay.

The conflict is usually approached as a branch or a theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

of the wider Portuguese Overseas War

The Portuguese Colonial War ( pt, Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War () or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation (), and also known as the Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican War of Independence, ...

, which also included the independence wars of Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

and of Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

.

It was a guerrilla war in which the Portuguese army and security forces waged a counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

campaign against armed groups mostly dispersed across sparsely populated areas of the vast Angolan countryside.António Pires NunesAngola 1966–74

/ref> Many atrocities were committed by all forces involved in the conflict. In the end, the Portuguese achieved overall military victory. In Angola, after the Portuguese withdrew, an armed conflict broke out among the nationalist movements. This war formally came to an end in January 1975 when the Portuguese government, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) signed the

Alvor Agreement

The Alvor Agreement, signed on 15 January 1975 in Alvor, Portugal, granted Angola independence from Portugal on 11 November and formally ended the 13-year-long Angolan War of Independence.

The agreement was signed by the Portuguese governme ...

. Informally, this civil war resumed by May 1975, including street fighting in Luanda and the surrounding countryside.

Background of the territory

In 1482, theKingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal ( la, Regnum Portugalliae, pt, Reino de Portugal) was a monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also kn ...

's caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing w ...

s, commanded by navigator Diogo Cão

Diogo Cão (; -1486), anglicised as Diogo Cam and also known as Diego Cam, was a Portuguese explorer and one of the most notable navigators of the Age of Discovery. He made two voyages sailing along the west coast of Africa in the 1480s, explori ...

, arrived in the Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

. Other expeditions followed, and close relations were soon established between the two kingdoms. The Portuguese brought firearms, many other technological advances, and a new religion, Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

. In return, the King of the Congo offered slaves, ivory and minerals.

Paulo Dias de Novais

Paulo Dias de Novais (c. 1510 – 9 May 1589), a fidalgo of the Royal Household, was a Portuguese colonizer of Africa in the 16th century and the first Captain-Governor of Portuguese Angola. He was the grandson of the explorer Bartolomeu Dias.

D ...

founded Luanda

Luanda () is the capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Angola's administrative centre, its chief seapo ...

in 1575 as . Novais occupied a strip of land with a hundred families of colonists and four hundred soldiers, and established a fortified settlement. The Portuguese crown granted Luanda the status of city in 1605. Several other settlements, forts and ports were founded and maintained by the Portuguese. Benguela

Benguela (; Umbundu: Luombaka) is a city in western Angola, capital of Benguela Province. Benguela is one of Angola's most populous cities with a population of 555,124 in the city and 561,775 in the municipality, at the 2014 census.

History

P ...

, a Portuguese fort from 1587, a town from 1617, was another important early settlement founded and ruled by Portugal.

The early period of Portuguese incursion was punctuated by a series of wars, treaties and disputes with local African rulers, particularly Nzinga Mbandi, who resisted Portugal with great determination. The conquest of the territory of contemporary Angola started only in the 19th century and was not concluded before the 1920s.

In 1834, Angola and the rest of the Portuguese overseas dominions received the status of overseas provinces of Portugal. From then on, the official position of the Portuguese authorities was always that Angola was an integral part of Portugal in the same way as were the provinces of the Metropole

A metropole (from the Greek '' metropolis'' for "mother city") is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of ...

(European Portugal). The status of province was briefly interrupted from 1926 to 1951, when Angola had the title of "colony" (itself administratively divided in several provinces), but it was recovered on 11 June 1951. The Portuguese constitutional revision of 1971 increased the autonomy of the province, which became the State of Angola.

Angola has always had very low population density. Despite having a territory larger than France and Germany combined, in 1960, Angola had just a population of 5 million, of which around 180,000 were whites, 55,000 were mixed race and the remaining were blacks. In the 1970s, the population had increased to 5.65 million, of which 450,000 were whites, 65,000 were mixed race and the remaining were blacks. Political scientist Gerald Bender wrote "... by the end of 1974 the white population of Angola would be approximately 335,000, or slightly more than half the number which has commonly been reported."

The provincial government of Angola was headed by the Governor-General, who had both executive and legislative powers, reporting to the Portuguese Government, through the Minister of the Overseas. He was assisted by a cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

made up of a Secretary-General (who also served as his deputy) and several provincial secretaries, each managing a given portfolio. There was a Legislative Council – including both appointed and elected members – with legislative responsibilities that were gradually increased in the 1960s and the 1970s. In 1972, it was transformed in the Legislative Assembly of Angola. There was also a Council of Government, responsible to advice the Governor-General in his legislative and executive responsibilities, which included the senior public officials of the province.

Despite being responsible for the police and other civil internal security forces, the Governor-General did not have military responsibilities, which were vested in the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Angola. The Commander-in-Chief reported directly to the Minister of National Defense and the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces. In some occasions however, the same person was appointed to fulfil both the roles of Governor-Geral and Commander-in-Chief, thus assuming both civil as military responsibilities.

In 1961, the local administration of Angola included the following districts

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions ...

: Cabinda, Congo, Luanda

Luanda () is the capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Angola's administrative centre, its chief seapo ...

, Cuanza Norte

The Cuanza Norte Province ( en, North Cuanza; umb, Konano Kwanza Volupale) is province of Angola. N'dalatando is the capital and the province has an area of 24,110 km² and a population of 443,386. Manuel Pedro Pacavira was born here and ...

, Cuanza Sul

Cuanza Sul Province ("South Cuanza"; Umbundu: Kwanza Kombuelo Volupale) is a province of Angola. It has an area of and a population of 1,881,873. Sumbe is the capital of the province. Don founded the province in 1769 as Novo Redondo.

Histo ...

, Malanje, Lunda, Benguela

Benguela (; Umbundu: Luombaka) is a city in western Angola, capital of Benguela Province. Benguela is one of Angola's most populous cities with a population of 555,124 in the city and 561,775 in the municipality, at the 2014 census.

History

P ...

, Huambo

Huambo, formerly Nova Lisboa (English: ''New Lisbon''), is the third-most populous city in Angola, after the capital city Luanda and Lubango, with a population of 595,304 in the city and a population of 713,134 in the municipality of Huambo (Cens ...

, Bié-Cuando-Cubango, Moxico, Moçâmedes

Moçâmedes is a city in southwestern Angola, capital of Namibe Province. The city's current population is 255,000 (2014 census). Founded in 1840 by the Portuguese colonial administration, the city was named Namibe between 1985 and 2016. Moç� ...

and Huíla. In 1962, the Congo District was divided in the Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

and Uige districts and that of Bié-Cuando-Cubando in the Bié and Cuando-Cubango districts. In 1970, the Cunene District was also created by the separation of the southern part of the Huíla District. Each was headed by a district governor, assisted by a district board. Following the Portuguese model of local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loc ...

, the districts were made of municipalities () and these were subdivided in civil parishes (), each administered by local council (respectively and ). In the regions where the necessary social and economic development had not yet been achieved, the municipalities and civil parishes were transitorily replaced, respectively, by administrative circles () and posts (), each of these governed by an official appointed by the government who had wide administrative powers, performing local government, police, sanitary, economical, tributary and even judicial roles. The circle administrators and the chiefs of administrative posts directed the local native auxiliary police officers known as "sepoy

''Sepoy'' () was the Persian-derived designation originally given to a professional Indian infantryman, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire.

In the 18th century, the French East India Company and its ot ...

s" (). In these regions, the traditional authorities – including native kings, rulers and tribal chief

A tribal chief or chieftain is the leader of a tribe, tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribe

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of western Afroeurasia.

Tribal societies are sometimes categori ...

s – were kept and integrated in the administrative system, serving as intermediaries between the provincial authorities and the local native populations.

Belligerents

Portuguese forces

The Portuguese forces engaged in the conflict included mainly the

The Portuguese forces engaged in the conflict included mainly the Armed Forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, but also the security and paramilitary forces.

Armed Forces

The Portuguese Armed Forces in Angola included land, naval and air forces, which came under the joint command of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Angola. Until 17 June 1961, there was not an appointed Commander-in-Chief, with the joint command in the early stages of the conflict being exercised by the commanders of the land forces, generals Monteiro Libório (until June 1961) and Silva Freire (from June to September 1961). From then on, the role of Commander-in-Chief was performed successively by the generals Venâncio Deslandes (1961–1962, also serving as Governor-General), Holbeche Fino (1962–1963), Andrade e Silva (1963–1965), Soares Pereira (1965–1970), Costa Gomes (1970–1972), Luz Cunha (1972–1974) and Franco Pinheiro (1974), all of them from the Army, except the first one who was from the Air Force. The Commander-in-Chief served as thetheatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

commander and coordinated the forces of the three branches stationed in the province, with the respective branch commanders serving as assistant commanders-in-chief. With the course of the conflict, the operational role of the Commander-in-Chief and of his staff was increasingly reinforced at the expense of the branch commanders. In 1968, the Military Area 1 – responsible for the Dembos rebelled area – was established under the direct control of the Commander-in-Chief and, from 1970, the military zones were also put under his direct control, with the Eastern Military Zone becoming a joint command. When the conflict erupted, the Portuguese Armed Forces in Angola only included 6500 men, of which 1500 were Metropolitans (Europeans) and the remaining were locals. By the end of the conflict, the number had increased to more than 65 000, of which 57.6% were Metropolitans and the remaining were locals.

The land forces in Angola constituted the 3rd Military Region of the Portuguese Army

The Portuguese Army ( pt, Exército Português) is the land component of the Armed Forces of Portugal and is also its largest branch. It is charged with the defence of Portugal, in co-operation with other branches of the Armed Forces. With it ...

(renamed "Military Region of Angola, RMA" in 1962). The Military Region was foreseen to include five subordinate regional territorial commands, but these had not yet been activated. The disposition of the army units in the province at the beginning of the conflict had been established in 1953, at that a time when no internal conflicts were expected to happen in Angola, with the Portuguese major military concerns being a foreseen conventional war in Europe against the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

. So, the previous organization of the former Colonial Military Forces based in company-sized units scattered across Angola, also performing internal security duties, had shift to one along conventional lines, based in three infantry regiments and several battalion-sized units of several arms concentrated in the major urban centers, aimed at being able to raise an expeditionary field division to be deployed from Angola to reinforce the Portuguese Army in Europe if a conventional war occurred. These regiments and other units were, however, mostly in cadre strength, serving as training centers for the conscript

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

s drafted in the province. During the conflict, they were responsible to raise the locally recruited field units. Besides the locally raised units, the Army forces in Angola included reinforcement units raised and sent from European Portugal. These were transitory units, mostly made of conscripts (including most of their junior officer

Junior officer, company officer or company grade officer refers to the lowest operational commissioned officer category of ranks in a military or paramilitary organization, ranking above non-commissioned officers and below senior officers.

The ...

s and non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

s), which existed only during the usual two-year period of tour of duty

For military personnel, a tour of duty is usually a period of time spent in combat or in a hostile environment. In an army, for instance, soldiers on active duty serve 24 hours a day, seven days a week for the length of their service commitment. ...

of their members, being disbanded afterwards. The great majority of these units were light infantry battalions and independent companies designated . These battalions and companies were designed to operate autonomously and isolated, without much support from the higher echelons, so having a strong service support component. They were deployed in a grid system () along the theatre of operations, with each one being responsible for a given area of responsibility

Area of responsibility (AOR) is a pre-defined geographic region assigned to Combatant commanders of the Unified Command Plan (UCP), that are used to define an area with specific geographic boundaries where they have the authority to plan and co ...

. Usually, a regiment-sized ( battlegroup) commanded a sector, with this being divided in several sub-sectors, each constituting the area of responsibility of a battalion. Each battalion, in turn, had its field companies dispersed by the sub-sector, each with part of it as its area of responsibility. From 1962, four intervention zones (Northern, Central, Southern and Eastern) were established – renamed "military zones" in 1967 – each grouping several sectors. Due to the low scale guerrilla nature of the conflict, the company became the main tactical unit, with the standard organization in three rifle and one support platoons, being replaced by one based in four identical sub-units known as "combat groups". The Army also fielded regular units of artillery, armored reconnaissance, engineering, communications, signal intelligence, military police and service support. Besides the regular units, the Army also fielded units of special forces. Initially, these consisted of companies of , trained for guerrilla and counter-insurgency warfare. The Army tried to extend the training of the special to all the light infantry units, so disbanding those companies in 1962. These proved, however, impracticable and soon other special forces were raised again in the form of the Commandos

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

. The Commandos and a few specially selected units were not deployed in grid, but served instead as mobile intervention units under the direct control of the higher echelons of command. An unconventional force also fielded by Army was the Dragoons of Angola, a special counterinsurgency horse unit raised in the middle 1960s.

The Portuguese Navy

The Portuguese Navy ( pt, Marinha Portuguesa, also known as ''Marinha de Guerra Portuguesa'' or as ''Armada Portuguesa'') is the naval branch of the Portuguese Armed Forces which, in cooperation and integrated with the other branches of the Port ...

forces were under the command of the Naval Command of Angola. These forces included the Zaire Flotilla (with patrol boats and landing craft operating in the river Zaire), naval assets (including frigates and corvettes deployed to Angola in rotation), Marines companies and Special Marines detachments. While the Marines companies served as regular naval infantry with the role of protecting the Navy's installations and vessels, the Special Marines were special forces, serving as mobile intervention units, specialized in amphibious assaults. The initial focus of the Navy was mainly the river Zaire, with the mission of interdicting the infiltration of guerrillas in Northern Angola from the bordering Republic of Zaire. Later, the Navy also operated in the rivers of Eastern Angola, despite it being a remote interior region at around 1000 km distance from the Ocean.

The Portuguese air assets in Angola were under the command of the 2nd Air Region of the

The Portuguese air assets in Angola were under the command of the 2nd Air Region of the Portuguese Air Force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 1 July

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

, with headquarters in Luanda. They included a central air base (the Air Base 9 at Luanda) and two sector air bases (the Base-Aerodrome 3 at Negage, Uíge and the Base-Aerodrome 4 at Henrique de Carvalho, Lunda). A fourth air base was being built ( Base-Aerodrome 10 at Serpa Pinto, Cuando-Cubando), but it was not completed before the end of the conflict. These bases controlled a number of satellite air fields, including maneuver and alternate aerodromes. Besides these, the Air Force also could count with a number of additional airfields, including those of some of the Army garrisons, in some of which air detachments were permanently deployed. The Air Force also maintained in Angola, the Paratrooper Battalion 21, which served as a mobile intervention unit, with its forces initially being deployed by parachute, but later being mainly used in air assaults by helicopter. The Air Force was supported by the voluntary air formations, composed of civil pilots, mainly from local flying clubs, who operated light aircraft mainly in air logistics support missions. In the beginning of the conflict, the Air Force had only a few aircraft stationed in Angola, including 25 F-84G

The Republic F-84 Thunderjet was an American turbojet fighter-bomber aircraft. Originating as a 1944 United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) proposal for a "day fighter", the F-84 first flew in 1946. Although it entered service in 1947, the Thun ...

jet fighter-bombers, six PV-2 Harpoon

The Lockheed Ventura is a twin-engine medium bomber and patrol bomber of World War II.

The Ventura first entered combat in Europe as a bomber with the RAF in late 1942. Designated PV-1 by the United States Navy (US Navy), it entered combat in 1 ...

bombers, six Nord Noratlas

The Nord Noratlas was a dedicated military transport aircraft, developed and manufactured by French aircraft manufacturer Nord Aviation.

Development commenced during the late 1940s with the aim of producing a suitable aircraft to replace the n ...

transport aircraft, six Alouette II

Alouette or alouettes may refer to:

Music and literature

* "Alouette" (song), a French-language children's song

* Alouette, a character in ''The King of Braves GaoGaiGar''

Aerospace

* SNCASE Alouette, a utility helicopter developed in France i ...

helicopters, eight T-6 light attack aircraft and eight Auster

Auster Aircraft Limited was a British aircraft manufacturer from 1938 to 1961.Willis, issue 122, p.55

History

The company began in 1938 at the Britannia Works, Thurmaston near Leicester, England, as Taylorcraft Aeroplanes (England) Limited, ma ...

light observation aircraft. By the early 1970s, it had available four F-84G, six PV-2 Harpoon, 13 Nord Noratlas, C-47

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (RAF, RAAF, RCAF, RNZAF, and SAAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II and remained in ...

and C-57 transport aircraft, 30 Alouette III

Alouette or alouettes may refer to:

Music and literature

* "Alouette" (song), a French-language children's song

* Alouette, a character in ''The King of Braves GaoGaiGar''

Aerospace

* SNCASE Alouette, a utility helicopter developed in France i ...

and Puma helicopters, 18 T-6 and 26 Dornier Do 27 observation aircraft. Despite the increase, the number of aircraft was always too few to cover the enormous Angolan territory, besides many being old aircraft difficult to maintain in flying conditions. From the late 1960s, the Portuguese forces in southern Angola were able to count with the support of helicopters and some other air assets of the South African Air Force

"Through hardships to the stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment ...

, with two Portuguese-South African joint air support centers being established.

Security forces

The security forces in Angola were under the control of the civil authorities, headed by the Governor-General of the province. The main of these forces engaged in the war was the Public Security Police (PSP) and thePIDE

The International and State Defense Police ( pt, Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado; PIDE) was a Portuguese security agency that existed during the '' Estado Novo'' regime of António de Oliveira Salazar. Formally, the main roles of th ...

(renamed DGS in 1969). By the middle of the 1960s, these forces included 10,000 PSP constables and 1,100 PIDE agents.

The PSP was the uniformed preventive police

Preventive police is that aspect of law enforcement intended to act as a deterrent to the commission of crime. Preventive policing is considered a defining characteristic of the modern police, typically associated with Robert Peel's London Metrop ...

of Angola. It was modeled after the European Portuguese PSP, but it covered the whole territory of the province, including its rural areas and not only the major urban areas as in the European Portugal. The PSP of Angola included a general-command in Luanda and district commands in each of the several district capitals, with a network of police stations and posts scattered along the territory. The Angolan PSP was reinforced with mobile police companies deployed by the European Portuguese PSP. The PSP also included the Rural Guard, which was responsible for the protection of farms and other agricultural companies. Besides this, the PSP was responsible to frame the district militias, which were employed mainly in the self-defense of villages and other settlements.

The PIDE (International and State Defense Police) was the Portuguese secret and border police. The PIDE Delegation of Angola, included a number of sub-delegations, border posts and surveillance posts. In the war, it operated as an intelligence service. The PIDE raised and controlled the '' Flechas'', a paramilitary unit of special forces made up of natives. The ''Flechas'' were initially intended to serve mostly as trackers, but due to their effectiveness they were increasingly employed in more offensive operations, including pseudo-terrorist operations.

Para-military and irregular forces

Besides the regular armed and security forces, there were a number of para-military and irregular forces, some of them under the control of the military and other controlled by the civil authorities. The OPVDCA ( Provincial Organization of Volunteers and Civil Defense of Angola) was a militia-type corps responsible for internal security andcivil defense

Civil defense ( en, region=gb, civil defence) or civil protection is an effort to protect the citizens of a state (generally non-combatants) from man-made and natural disasters. It uses the principles of emergency operations: prevention, mit ...

roles, with similar characteristics to those of the Portuguese Legion existing in European Portugal. It was under the direct control of the Governor-General of the province. Its origin was the Corps of Volunteers organized in the beginning of the conflict, which became the Provincial Organization of Volunteers in 1962, also assuming the role of civil defense in 1964, when it became the OPVDCA. It was made up of volunteers that served in part-time, most of these being initially whites, but latter becoming increasingly multi-racial. In the conflict, the OPVDCA was mainly employed in the defense of people, lines of communications and sensitive installations. It included a central provincial command and a district command in each of the Angolan districts. It is estimated that by the end of the conflict there were 20,000 OPVDCA volunteers.

The irregular paramilitary forces, included a number of different types of units, with different characteristics. Under military control, were the Special Groups (GE) and the Special Troops (TE). The GE were platoon-sized combat groups of special forces made up of native volunteers, which operated in Eastern Angola, usually attached to Army units. The TE had similar characteristics, but were made up of defectors from FNLA, operating in Cabinda and Northern Angola. Under the control of the civil authorities were the (Faithfuls) and the (Loyals). The was a force made up mostly of exiled Katangese gendarmes from the Front for Congolese National Liberation

The Congolese National Liberation Front (french: Front de libération nationale congolaise, FLNC) is a political party funded by rebels of Katangese origin and composed of ex-members of the Katangese Gendarmerie. It was active mainly in Angola an ...

, which opposed Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

regime, being organized in three battalions. The was a force made up of political exiles from Zambia.

Race and ethnicity in the Portuguese Armed Forces

From 1900 to the early 1950s the Portuguese maintained a separate colonial army in their African possessions, consisting mainly of a limited number of (native companies). Officers and senior NCOs were seconded from the metropolitan army, while junior NCOs were mainly drawn from Portuguese settlers resident in the overseas territories. The rank and file were a mixture of black African volunteers and white conscripts from the settler community doing their obligatory military service. Black were in theory also liable to conscription but in practice only a limited number were called on to serve. With the change in official status of the African territories from colonies to overseas provinces in 1951, the colonial army lost its separate status and was integrated into the regular forces of Portugal itself. The basis of recruitment for the overseas units remained essentially unchanged. According to the Mozambican historian João Paulo Borges Coelho, the Portuguese colonial army was segregated along lines of race and ethnicity. Until 1960, there were three classes of soldiers: commissioned soldiers (European and African whites), overseas soldiers (black African or ), and native soldiers (Africans who were part of the regime). These categories were renamed to 1st, 2nd and 3rd class in 1960—which effectively corresponded to the same classification. Later, although skin colour ceased to be an official discrimination, in practice the system changed little—although from the late 1960s onward blacks were admitted as ensigns (), the lowest rank in the hierarchy of commissioned officers.Coelho, João Paulo Borges, ''African Troops in the Portuguese Colonial Army, 1961–1974: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique'', Portuguese Studies Review 10 (1) (2002), pp. 129–50 Numerically, black soldiers never amounted to more than 41% of the Colonial army, rising from just 18% at the outbreak of the war. Coelho noted that perceptions of African soldiers varied a good deal among senior Portuguese commanders during the conflict in Angola, Guinea and Mozambique. General Costa Gomes, perhaps the most successful counterinsurgency commander, sought good relations with local civilians and employed African units within the framework of an organized counter-insurgency plan. General Spínola, by contrast, appealed for a more political and psycho-social use of African soldiers. General Kaúlza, the most conservative of the three, feared African forces outside his strict control and seems not to have progressed beyond his initial racist perception of the Africans as inferior beings. Native African troops, although widely deployed, were initially employed in subordinate roles as enlisted troops or noncommissioned officers. As the war went on, an increasing number of native Angolans rose to positions of command, though of junior rank. After 500 years of colonial rule, Portugal had failed to produce any native black governors, headmasters, police inspectors, or professors; it had also failed to produce a single commander of senior commissioned rank in the overseas Army. Here Portuguese colonial administrators fell victim to the legacy of their own discriminatory and limited policies in education, which largely barred indigenous Angolans from an equal and adequate education until well after the outbreak of the insurgency. By the early 1970s, the Portuguese authorities had fully perceived these flaws as wrong and contrary to their overseas ambitions in Portuguese Africa, and willingly accepted a truecolor blindness

Color blindness or color vision deficiency (CVD) is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. It can impair tasks such as selecting ripe fruit, choosing clothing, and reading traffic lights. Color blindness may make some aca ...

policy with more spending in education and training opportunities, which started to produce a larger number of black high-ranked professionals, including military personnel.

Nationalist and separatist forces

UPA/FNLA

UPA was created on 7 July 1954, as the Union of the Peoples of Northern Angola, byHolden Roberto

Álvaro Holden Roberto (January 12, 1923 – August 2, 2007) was an Angolan politician who founded and led the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) from 1962 to 1999. His memoirs are unfinished.

Early life

Roberto, son of Garcia Diasiwa ...

, a descendant of the old Kongo Royal House, who was born in Northern Angola but who lived since his early childhood in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

, where he came to work for the local colonial authorities. In 1958, the movement adopts a more embracing designation, becoming the Union of the Peoples of Angola (UPA). In 1960, Holden Roberto signed an agreement with the MPLA for the two movements to fight together against the Portuguese forces, but he ended fighting alone. In 1962, UPA merges with the Democratic Party of Angola, becoming the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), assuming itself as a pro-American and anti-Soviet organization. In the same year, it creates the Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (GRAE). UPA and later FNLA was mainly supported by the Bakongo

The Kongo people ( kg, Bisi Kongo, , singular: ; also , singular: ) are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have lived a ...

ethnic group which occupied the regions of the old Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

, including the Northwestern and Northern Angola, as well as parts of the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Belgian Congos. It had always strong connections with the former Belgian Congo (named Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

from 1971), including due to Holden Roberto being friend and brother in law of Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

.

The armed branch of FNLA was the National Liberation Army of Angola (ELNA). It was mainly supported by Congo/Zaire—where its troops were based and trained—and by Algeria. They were financed by the US and—despite considering themselves anti-communists—received weapons from the Eastern European countries.

MPLA

The People's Movement of Liberation of Angola (MPLA) was founded in 1956, by the merging of the Party of the United Struggle for Africans in Angola (PLUA) and the Angolan Communist Party (PCA). The MPLA was an organization of theleft-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in ...

, which included mixed race and white members of the Angolan ''intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

'' and urban elites, supported by the Ambundu

The Ambundu or Mbundu ( Mbundu: or , singular: (distinct from the Ovimbundu) are a Bantu people living in Angola's North-West, North of the river Kwanza. The Ambundu speak Kimbundu, and most also speak the official language of the countr ...

and other ethnic groups of the Luanda, Bengo, Cuanza Norte, Cuanza Sul and Mallange districts. It was headed by Agostinho Neto

António Agostinho da Silva Neto (17 September 1922 – 10 September 1979) was an Angolan politician and poet. He served as the first president of Angola from 1975 to 1979, having led the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) i ...

(president) and Viriato da Cruz

Viriato Clemente da Cruz (25 March 1928 – 13 June 1973) was an Angolan poet and politician, who was born in Kikuvo, Porto Amboim, Portuguese Angola, and died in Beijing, People's Republic of China. He is considered one of the most important Ango ...

(secretary-general), both Portuguese-educated urban intellectuals. It was mainly externally supported by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, with its tentative to receive support from the United States failing, as these were already supporting UPA/FNLA.

The armed wing of the MPLA was the People's Army of Liberation of Angola (EPLA). In its peak, the EPLA included around 4500 fighters, being organized in military regions. It was mainly equipped with Soviet weapons, mostly received through Zambia, which included Tokarev pistol

The TT-30,, "7.62 mm Tokarev self-loading pistol model 1930", TT stands for Tula-Tokarev) commonly known simply as the Tokarev, is an out-of-production Soviet semi-automatic pistol. It was developed in 1930 by Fedor Tokarev as a service pist ...

, PPS submachine gun

The PPS (Russian: ППС – "Пистолет-пулемёт Судаева" or "Pistolet-pulemyot Sudayeva", in English: "Sudayev's submachine-gun") is a family of Soviet submachine guns chambered in 7.62×25mm Tokarev, developed by Alexei Su ...

s, Simonov automatic rifles, Kalashnikov assault rifles, machine-guns, mortars, rocket-propelled grenade

A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) is a shoulder-fired missile weapon that launches rockets equipped with an explosive warhead. Most RPGs can be carried by an individual soldier, and are frequently used as anti-tank weapons. These warheads a ...

s, anti-tank mine

An anti-tank mine (abbreviated to "AT mine") is a type of land mine designed to damage or destroy vehicles including tanks and armored fighting vehicles.

Compared to anti-personnel mines, anti-tank mines typically have a much larger explosive c ...

s and anti-personnel mine

Anti-personnel mines are a form of mine designed for use against humans, as opposed to anti-tank mines, which are designed for use against vehicles. Anti-personnel mines may be classified into blast mines or fragmentation mines; the latter may ...

s

UNITA

The Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) was created in 1966 byJonas Savimbi

Jonas Malheiro Savimbi (; 3 August 1934 – 22 February 2002) was an Angolan revolutionary politician and rebel military leader who founded and led the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). UNITA waged a guerrilla war agai ...

, a dissident of FNLA. Jonas Savimbi was the Foreign Minister of the GRAE but entered in course of clash with Holden Roberto, accusing him of having complicity with the US and of following an imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

policy. Savimbi was member of the Ovimbundu

The Ovimbundu, also known as the Southern Mbundu, are a Bantu ethnic group who live on the Bié Plateau of central Angola and in the coastal strip west of these highlands. As the largest ethnic group in Angola, they make up 38 percent of the ...

tribe of Central and Southern Angola, son of an Evangelic pastor, who went to study medicine in European Portugal, although never graduating.

The Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FALA) constituted the armed branch of UNITA. They had a small number of fighters and were not well equipped. Its high difficulties led Savimbi to make agreements with the Portuguese authorities, focusing more in fighting MPLA.

When the war ended, UNITA was the only one of the nationalist movements that was able to maintain forces operating inside the Angolan territory, with the forces of the remaining movements being eliminated or expelled by the Portuguese Forces.

FLEC

The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) was founded in 1963, by the merging of the Movement for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (MLEC), the Action Committee of the Cabinda National Union (CAUNC) and the Mayombe National Alliance (ALLIAMA). On the contrary of the remaining three movements, FLEC did not fight for the independence of the whole Angola, but only for the independence of Cabinda, which it considered a separate country. Although its activities started still before the withdrawal of Portugal from Angola, the military actions of FLEC occurred mainly after, being aimed against the Angolan armed and security forces. FLEC is the only of the nationalist and separatist movements that still maintains a guerrilla warfare until today.RDL

The Eastern Revolt (RDL) was a dissident wing of the MPLA, created in 1973, under the leadership ofDaniel Chipenda

Daniel Chipenda (15 May 1931, Lobito - 28 February 1996) fought in the Angolan War of Independence, serving as the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola's (MPLA) field commander in the Eastern Front before founding and leading the Eastern ...

, in opposition to the line of Agostinho Neto

António Agostinho da Silva Neto (17 September 1922 – 10 September 1979) was an Angolan politician and poet. He served as the first president of Angola from 1975 to 1979, having led the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) i ...

. A second dissident wing was the Active Revolt, created at the same time.

Pre-war events

International politics

The international politics of the late 1940s and 1950s was marked by theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

and the wind of change in the European colonies in Asia and Africa.

In October 1954, the Algerian War

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

was initiated by a series of explosions in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

. This conflict would lead to the presence of more than 400,000 French military in Algeria until its end in 1962. Foreseeing a similar conflict in its African territories, the Portuguese military paid acute attention to this war, sending observers and personnel to be trained in the counter-insurgence warfare tactics employed by the French.

In 1955, the Bandung Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference ( id, Konferensi Asia–Afrika)—also known as the Bandung Conference—was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–2 ...

was held in Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, with the participation of 29 Asian and African countries, most of which were newly independent. The conference promoted the Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and opposed colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

or neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, ...

. It was an important step towards the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

.

Following the admission of Portugal to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

in December 1955, the Secretary-General

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

officially asked the Portuguese Government if the country had non-self-governing territories under its administration. Maintaining consistency with its official doctrine that all Portuguese overseas provinces were an integral part of Portugal as was the Portuguese European territory, the Portuguese Government responded that Portugal did not have any territories that could be qualified as non-self-governing and so it did not have any obligation of providing any information requested under the Article 73 of the United Nations Charter.

In 1957, Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

(former British Gold Cost) becomes the first European colony in Africa to achieve independence, under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An ...

. In 1958, he organized the Conference of African Independent States, which aimed to be the African Bandung.

The former Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

and northern neighbor of Angola became independent in 1960, as the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

(known as "Congo-Léopoldville" and later "Congo-Kinshasa", being renamed " Republic of Zaire" in 1971), with Joseph Kasa-Vubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of the Kon ...

as president and Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

as prime-minister. Immediately after independence, a number of violent disturbances occurred leading to the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

. The white population became a target, with more than 80,000 Belgian residents being forced to flee from the country. The Katanga seceded under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe (sometimes written Tshombé) (10 November 1919 – 29 June 1969) was a Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of Katanga from 1960 to 1963 and as prime minister of the D ...

. The crisis led to the intervention of United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

and Belgian military forces. The Congolese internal conflicts would culminate with the ascension to power of Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

in 1965.

John F. Kennedy was inaugurated as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

on 20 January 1961. His Administration started to support the African nationalist movements, with the objective of neutralizing the increasing Soviet influence in Africa. Regarding Angola, the United States started to give direct support to the UPA and assumed an hostile attitude against Portugal, forbidding it to use American weapons in Africa.

In 1964, Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesi ...

became independent as Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

, under the leadership of Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Diss ...

. From then on, Angola was almost entirely surrounded by countries with regimes hostile to Portugal, the exception being South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

.

Internal politics and rise of Angolan nationalism

The Portuguese Colonial Act – passed on 13 June 1933 – defined the relationship between the Portuguese overseas territories and the metropole, until being revised in 1951. The Colonial Act reflected an imperialistic view of the overseas territories typical among the European colonial powers of the late 1920s and 1930s. During the period in which it was in force, the Portuguese overseas territories lost the status of "provinces" that they have had since 1834, becoming designated "colonies", with the whole Portuguese overseas territories becoming officially designated " Portuguese Colonial Empire". The Colonial Act subtly recognized the supremacy of the Portuguese over native people, and even if the natives could pursue all studies including

The Portuguese Colonial Act – passed on 13 June 1933 – defined the relationship between the Portuguese overseas territories and the metropole, until being revised in 1951. The Colonial Act reflected an imperialistic view of the overseas territories typical among the European colonial powers of the late 1920s and 1930s. During the period in which it was in force, the Portuguese overseas territories lost the status of "provinces" that they have had since 1834, becoming designated "colonies", with the whole Portuguese overseas territories becoming officially designated " Portuguese Colonial Empire". The Colonial Act subtly recognized the supremacy of the Portuguese over native people, and even if the natives could pursue all studies including university

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

, the ''de facto'' situation was of clear disadvantage due to deep cultural and social differences between most of the traditional indigenous communities and the ethnic Portuguese living in the Angola.

Due to its imperialist orientation, the Colonial Act started to be called into question. In 1944, José Ferreira Bossa

José Silvestre Ferreira Bossa GOC (Safara, Moura, 20 July 1894 - 14 February 1970) was governor of Portuguese India and the Colonial Minister during the Estado Novo government of António de Oliveira Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar ...

, former Minister of the Colonies, proposed the revision of the Act, including the end up of the designation "colonies" and the resume of the traditional designation "overseas provinces". On 11 June 1951, a new law passed in the Portuguese National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

reviewed the Constitution, finally repulsing the Colonial Act. As part of these, the provincial status was returned to all Portuguese overseas territories. By this law, the Portuguese territory of Angola ceased to be called (Colony of Angola) and started again to be officially called (Province of Angola).

In 1948, Viriato da Cruz

Viriato Clemente da Cruz (25 March 1928 – 13 June 1973) was an Angolan poet and politician, who was born in Kikuvo, Porto Amboim, Portuguese Angola, and died in Beijing, People's Republic of China. He is considered one of the most important Ango ...

and others formed the Movement of Young Intellectuals, an organization that promoted Angolan culture. Nationalists sent a letter to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

calling for Angola to be given protectorate status under UN supervision.

In the 1950s, a new wave of Portuguese settlement in all of Portuguese Africa, including the overseas province of Angola, was encouraged by the ruling government of António de Oliveira Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar (, , ; 28 April 1889 – 27 July 1970) was a Portuguese dictator who served as President of the Council of Ministers from 1932 to 1968. Having come to power under the ("National Dictatorship"), he reframed the re ...

.

In 1953, Angolan separatists founded the Party of the United Struggle for Africans in Angola (PLUA), the first political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

to advocate Angolan independence from Portugal. In 1954, ethnic Bakongo

The Kongo people ( kg, Bisi Kongo, , singular: ; also , singular: ) are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have lived a ...

nationalists in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

and Angola formed the Union of Peoples of Northern Angola (UPA), which advocated the independence of the historical Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

, which included other territories outside the Portuguese overseas province of Angola.

During 1955, Mário Pinto de Andrade

Mário Coelho Pinto de Andrade (21 August 1928 – 26 August 1990) was an Angolan poet and politician.

Biography

He was born in Golungo Alto, in Portuguese Angola, and studied philosophy at the University of Lisbon and sociology at the Sorbo ...

and his brother Joaquim

Joaquim is the Portuguese and Catalan version of Joachim and may refer to:

* Alberto Joaquim Chipande, politician

* Eduardo Joaquim Mulémbwè, politician

* Joaquim Agostinho (1943–1984), Portuguese professional bicycle racer

* Joaquim Amat ...

formed the Angolan Communist Party

Angolan Communist Party (in Portuguese: ''Partido Comunista Angolano'') was an underground political party in Portuguese Angola (during the Estado Novo regime), founded in October 1955, under influence from the Portuguese Communist Party. PCA wa ...

(PCA). In December 1956 PLUA merged with the PCA to form the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social dem ...

(MPLA). The MPLA, led by da Cruz, Mário Andrade, Ilidio Machado, and Lúcio Lara

Lúcio Rodrigo Leite Barreto de Lara (April 9, 1929 – February 27, 2016), also known by the pseudonym Tchiweka, was a physicist-mathematician, politician, professor, anti-colonial ideologist and one of the founding members (and president) of t ...

, derived support from the Ambundu

The Ambundu or Mbundu ( Mbundu: or , singular: (distinct from the Ovimbundu) are a Bantu people living in Angola's North-West, North of the river Kwanza. The Ambundu speak Kimbundu, and most also speak the official language of the countr ...

and in Luanda

Luanda () is the capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Angola's administrative centre, its chief seapo ...

.

In March 1959, when inaugurating the new military shooting range of Luanda, the Governor-General of Angola, Sá Viana Rebelo, made the famous Shooting Range Speech, where he predicted a possible conflict in Angola.

General Monteiro Libório assumed the command of the land forces of Angola, with prerogatives of commander-in-chief, in September 1959. He would be the Portuguese military commander in office when the conflict erupts.

Álvaro Silva Tavares assumed the office of Governor-General of Angola in January 1960, being the holder of the office when the conflict erupted.

During January 1961, Henrique Galvão

Henrique Carlos da Mata Galvão (4 February 1895 – 25 June 1970) was a Portuguese military officer, writer and politician. He was initially a supporter but later become one of the strongest opponents of the Portuguese Estado Novo (Portugal), Es ...

, heading a group of operatives of the DRIL

@dril is a pseudonymous Twitter user best known for his idiosyncratic style of absurdist humor and non sequiturs. The account, its author, and the character associated with the tweets are all commonly referred to as dril (the account's identi ...

oppositionist movement, hijacked the Portuguese liner ''Santa Maria''. The intention of Galvão was to set sail to Angola, where he would disembark and establish a rebel Portuguese government in opposition to Salazar, but he was forced to head to Brazil, where he liberated the crew and passengers in exchange for political asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another entit ...

.

Feeling the need of having forces trained in counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

operations, the Portuguese Army created the Special Operations Troops Centre in April 1960, where companies of special forces (baptized ) started preparations. The first three companies of special (CCE) were dispatched to Angola in June 1960, mainly due to the Congo Crisis. Their main mission was to protect the Angolan regions bordering the ex-Belgian Congo, each being stationed in Cabinda (1st CCE), in Toto, Uíge (2nd CCE) and Malanje (3rd CCE).

The Baixa de Cassanje revolt

Although usually considered as an event that predates the Angolan War of Independence, some authors consider the Baixa de Cassanje revolt (also known as the "Maria's War") as the initial event of the Conflict. It was a labour conflict, not related with the claiming for the independence of Angola. The Baixa do Cassanje was a rich agricultural region of the Malanje District, bordering the ex-Belgian Congo, with approximately the size ofMainland Portugal

Continental Portugal ( pt, Portugal continental, ) or mainland Portugal comprises the bulk of the Portuguese Republic, namely that part on the Iberian Peninsula and so in Continental Europe, having approximately 95% of the total population and 9 ...

, which was the origin of most of the cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

production of Angola. The region's cotton fields were in the hands of the Cotonang - General Company of the Cottons of Angola, a company mostly held by Belgian capital and which employed many natives. Despite its contribution for the development of the region, Cotonang had been accused several times of disrespecting the labour legislation regarding working conditions of its employees, causing it to become under the investigation of the Portuguese authorities, but with no relevant actions against it being yet taken.

Feeling discontent with Cotonang, in December 1960, many of its workers started to boycott work, demanding better working conditions and higher wages. The discontent was seized by infiltrated indoctrinators of the Congolese PSA (African Solidarity Party) to foment an uprising of the local peoples. At that time, the only Portuguese Army unit stationed in the region was the 3rd Special Company (3rd CCE), tasked with the patrolling and protection of the border with the ex-Belgian Congo. Despite receiving complains from local whites who felt their security threatened, the Governor of the Malanje District, Júlio Monteiro – a mixed race Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

an – did not authorize the 3rd CCE to act against the rebels and also forbade the acquisition of self-defense weapons by the white population. From 9 to 11 January 1961, the situation worsened, with the murder of a mixed race Cotonang foreman and with the surrounding of a 3rd CCE patrol by hundreds of rebels. Finally, on 2 February, the clashes between the rebels and the security forces erupted, with the first shots being fired, causing 11 deaths. By that time, the uprising had spread to the whole Malanje District and threatened to spread to the neighboring districts. The rebel leaders took advantage of the superstitious beliefs of most of their followers to convince them that the bullets of the Portuguese military forces were made of water and so could do no harm. Presumably due to this belief, the rebels, armed with machetes

Older machete from Latin America

Gerber machete/saw combo

Agustín Cruz Tinoco of San Agustín de las Juntas, Oaxaca">San_Agustín_de_las_Juntas.html" ;"title="Agustín Cruz Tinoco of San Agustín de las Juntas">Agustín Cruz Tinoco of San ...

and ''canhangulos'' (home-made shotguns), attacked the military en masse, in the open field, without concern for their own protection, falling under the fire of the troops.

Given the limitations of the 3rd CCE to deal with the uprising in such a large region, the Command of the 3rd Military Region in Luanda decided to organize an operation with a stronger military force to subjugate it. A provisional battalion under the command of Major Rebocho Vaz was organized by the Luanda Infantry Regiment, integrating the 3rd CCE, the 4th CCE (stationed in Luanda) and the 5th CCE (that was still en route from the Metropole to Angola). On 4 February, the 4th CCE was already embarked in the train ready to be dispatched to Malanje, when an uprising at Luanda erupted, with several prisons and Police facilities being stormed. Despite the indefinite situation at Luanda and despite having few combat units available there, General Libório, commander of the 3rd Military Region decided to go forward with the sending of the 4th CCE to Malanje, which arrived there on 5 February. The provisional battalion started gradually the operations to subdue the uprising.

The land forces were supported by the Portuguese Air Force, which employed Auster light observation and PV-2 ground attack aircraft. The military forces were able to assume the control of the region by 11 February. By the 16th, the provisional battalion was finally reinforced with the 5th CCE which had been held in Luanda as a reserve force after disembarking in Angola. Baixa do Cassanje was officially considered pacified on 27 February. The anti-Portuguese forces claimed that, during the subduing of the uprising, the Portuguese military bombed villages in the area, using napalm