Ancient Slavs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The early Slavs were a diverse group of

The early Slavs were known to the

The early Slavs were known to the

The Proto-Slavic

The Proto-Slavic

In the archaeological literature, attempts have been made to assign an early Slavic character to several cultures in a number of time periods and regions. The Prague-Korchak cultural horizon encompasses postulated early Slavic cultures from the Elbe to the Dniester, in contrast with the Dniester-to-Dnieper Prague-Penkovka. "Prague culture" in a narrow sense, refers to western Slavic material grouped around Bohemia, Moravia and western Slovakia, distinct from the Mogilla (southern Poland) and Korchak (central Ukraine and southern Belarus) groups further east. The Prague and Mogilla groups are seen as the archaeological reflection of the 6th-century Western Slavs.

The 2nd-to-5th-century

In the archaeological literature, attempts have been made to assign an early Slavic character to several cultures in a number of time periods and regions. The Prague-Korchak cultural horizon encompasses postulated early Slavic cultures from the Elbe to the Dniester, in contrast with the Dniester-to-Dnieper Prague-Penkovka. "Prague culture" in a narrow sense, refers to western Slavic material grouped around Bohemia, Moravia and western Slovakia, distinct from the Mogilla (southern Poland) and Korchak (central Ukraine and southern Belarus) groups further east. The Prague and Mogilla groups are seen as the archaeological reflection of the 6th-century Western Slavs.

The 2nd-to-5th-century

Archaeology of the Slavic Migrations

, in: Encyclopedia of Slavic Languages and Linguistics Online, Editor-in-Chief Marc L. Greenberg, BRILL, 2020, quote: "There are two specific aspects of the archaeology of Slavic migrations: the movement of the populations of the Slavic cultural model and the diffusion of this model amid non-Slavic populations. Certainly, both phenomena occurred; however, a pure diffusion of the Slavic model would hardly be possible, in any case in which a long period of time when the populations of different cultural traditions lived close to one another is assumed. Moreover, archaeologists researching Slavic antiquities do not accept the ideas produced by the "diffusionists," because most of the champions of the diffusion model know the specific archaeological materials poorly, so their works leave room for a number of arbitrary interpretations (for details, see Pleterski 2015: 232)." According to the processual viewpoint which emphasizes the culture-social model of ethnogenesis, there is "no need to explain culture change exclusively in terms of migration and population replacement". It argues that the Slavic expansion was primarily "a linguistic spread". One of the theories used to explain language replacement is that a dominant Slavic elite diaspora managed to spread, conquer and slavicize various communities. A more extreme hypothesis is argued by

There is no indication of Slavic chiefs in any of the Slavic raids before AD 560, when Pseudo-Caesarius's writings mentioned their chiefs but described the Slavs as living by their own law and without the rule of anyone.

The

There is no indication of Slavic chiefs in any of the Slavic raids before AD 560, when Pseudo-Caesarius's writings mentioned their chiefs but described the Slavs as living by their own law and without the rule of anyone.

The

Early Slavic settlements were no bigger than . Settlements were often temporary, perhaps reflected their itinerant form of agriculture, and were often along rivers. They were characterised by sunken buildings, known as ''Grubenhäuser'' in German or ''poluzemlianki'' in Russian. Built over a rectangular pit, they varied from in area and could accommodate a typical

Early Slavic settlements were no bigger than . Settlements were often temporary, perhaps reflected their itinerant form of agriculture, and were often along rivers. They were characterised by sunken buildings, known as ''Grubenhäuser'' in German or ''poluzemlianki'' in Russian. Built over a rectangular pit, they varied from in area and could accommodate a typical

Wood, leather, metal and ceramic work were all skillfully practiced by the Early Slavs. Pottery was made by craftsmen, or women, possibly in domestic workshops. Clay was mixed with course material, such as sand, crushed rock, to improve the qualities. Clay was worked by hand and roughly smoothed after completion, clay vessels also made with assistance of pottery wheels. After they were dried they were baked at a low temperature in bone-fire kilns. Pottery was produced not only by craftsmen, but also ordinary people as it did not require extensive practice, other crafts however were produced by professional craftsmen.

Metalworking was very important, as it was required to make tools and weapons. Iron was needed by every tribe, and it was produced by smiths using local ore, which was primarily bog ore. Once the ore had been turned into usable iron and slag removed, it was made into bars. Smiths made many types of products such as knives, tools, decorative items as well as weapons, which were not always made by separate weapon smiths. Broken tools were reforged, as iron was a valuable resource.

Houses, as well as their inside fittings and everyday items were made from wood. Carved bowls, vessels and beautifully made dippers were common in most homes. Leather and textiles, made of both linen and wool were made into carpets, blankets, overcoats and other clothing. Spindlewhorls were used to make thread in the home. Glass beads were crafted, and were often used as trade goods.

Wood, leather, metal and ceramic work were all skillfully practiced by the Early Slavs. Pottery was made by craftsmen, or women, possibly in domestic workshops. Clay was mixed with course material, such as sand, crushed rock, to improve the qualities. Clay was worked by hand and roughly smoothed after completion, clay vessels also made with assistance of pottery wheels. After they were dried they were baked at a low temperature in bone-fire kilns. Pottery was produced not only by craftsmen, but also ordinary people as it did not require extensive practice, other crafts however were produced by professional craftsmen.

Metalworking was very important, as it was required to make tools and weapons. Iron was needed by every tribe, and it was produced by smiths using local ore, which was primarily bog ore. Once the ore had been turned into usable iron and slag removed, it was made into bars. Smiths made many types of products such as knives, tools, decorative items as well as weapons, which were not always made by separate weapon smiths. Broken tools were reforged, as iron was a valuable resource.

Houses, as well as their inside fittings and everyday items were made from wood. Carved bowls, vessels and beautifully made dippers were common in most homes. Leather and textiles, made of both linen and wool were made into carpets, blankets, overcoats and other clothing. Spindlewhorls were used to make thread in the home. Glass beads were crafted, and were often used as trade goods.

The Slavs had many musical instruments as recorded in historical chronicles:

"They have different kinds of lutes, pan pipes and flutes a cubit long. Their lutes have eight strings. They drink mead. They play their instruments during the incineration of their dead and claim that their rejoicing attests the mercy of the Lord to the dead."

-Ibn Rusta

"They have different kinds of wind and string instruments. They have a wind instrument more than two cubits long, and an eight-stringed instrument whose sounding board is flat, not convex."

-Ibrahim Ibn Ya'qub

Theophylact Simocatta mentioned of Slavs bearing lyres: "Lyres were their baggage"

The Slavs burned their dead. Although the Slavic

The Slavs had many musical instruments as recorded in historical chronicles:

"They have different kinds of lutes, pan pipes and flutes a cubit long. Their lutes have eight strings. They drink mead. They play their instruments during the incineration of their dead and claim that their rejoicing attests the mercy of the Lord to the dead."

-Ibn Rusta

"They have different kinds of wind and string instruments. They have a wind instrument more than two cubits long, and an eight-stringed instrument whose sounding board is flat, not convex."

-Ibrahim Ibn Ya'qub

Theophylact Simocatta mentioned of Slavs bearing lyres: "Lyres were their baggage"

The Slavs burned their dead. Although the Slavic

Rus law was based on Early Slavic

Rus law was based on Early Slavic

Дьяконов М.А. Очерки общественного и государственного строя Древней Руси

/ Изд. 4-е, испр. и доп. – СПб.: Юридич. кн. склад Право, 1912. – XVI, 489 с.). One such customary law was the law of hospitality, which was very important to the tribal Slavs. If a tribe mistreated any guest, they would be attacked by a neighbouring tribe for their dishonour. Ibn Rusta wrote of Slavic law in c 903-918: "The ruler levies fixed taxes every year. Every man must supply one of his daughter's gowns. If he has a son, his clothing must be offered. If he has no children, he gives one of his wife's robes. In this country thieves are strangled or exiled to Jira ura by the Urals? the region most remote from this principality."

Our understanding of Early Slavic warfare is based on both the writings of ancient authors and archeological discoveries.

Early barbarian warrior bands, typically numbering 200 or less, were intended for fast penetration into enemy territory and an equally-quick withdrawal. The Slavs favoured ambush and guerrilla tactics, preferring to fight in dense woodland or marsh. However, victories in the open, sieges and hand-to-hand fighting were also achieved. They often attacked their enemy's flank, and were cunning in devising stratagems. The Slavs also used siege engines, such as siege towers and ladders as described by Procopius and St. Demetrius.

Our understanding of Early Slavic warfare is based on both the writings of ancient authors and archeological discoveries.

Early barbarian warrior bands, typically numbering 200 or less, were intended for fast penetration into enemy territory and an equally-quick withdrawal. The Slavs favoured ambush and guerrilla tactics, preferring to fight in dense woodland or marsh. However, victories in the open, sieges and hand-to-hand fighting were also achieved. They often attacked their enemy's flank, and were cunning in devising stratagems. The Slavs also used siege engines, such as siege towers and ladders as described by Procopius and St. Demetrius.

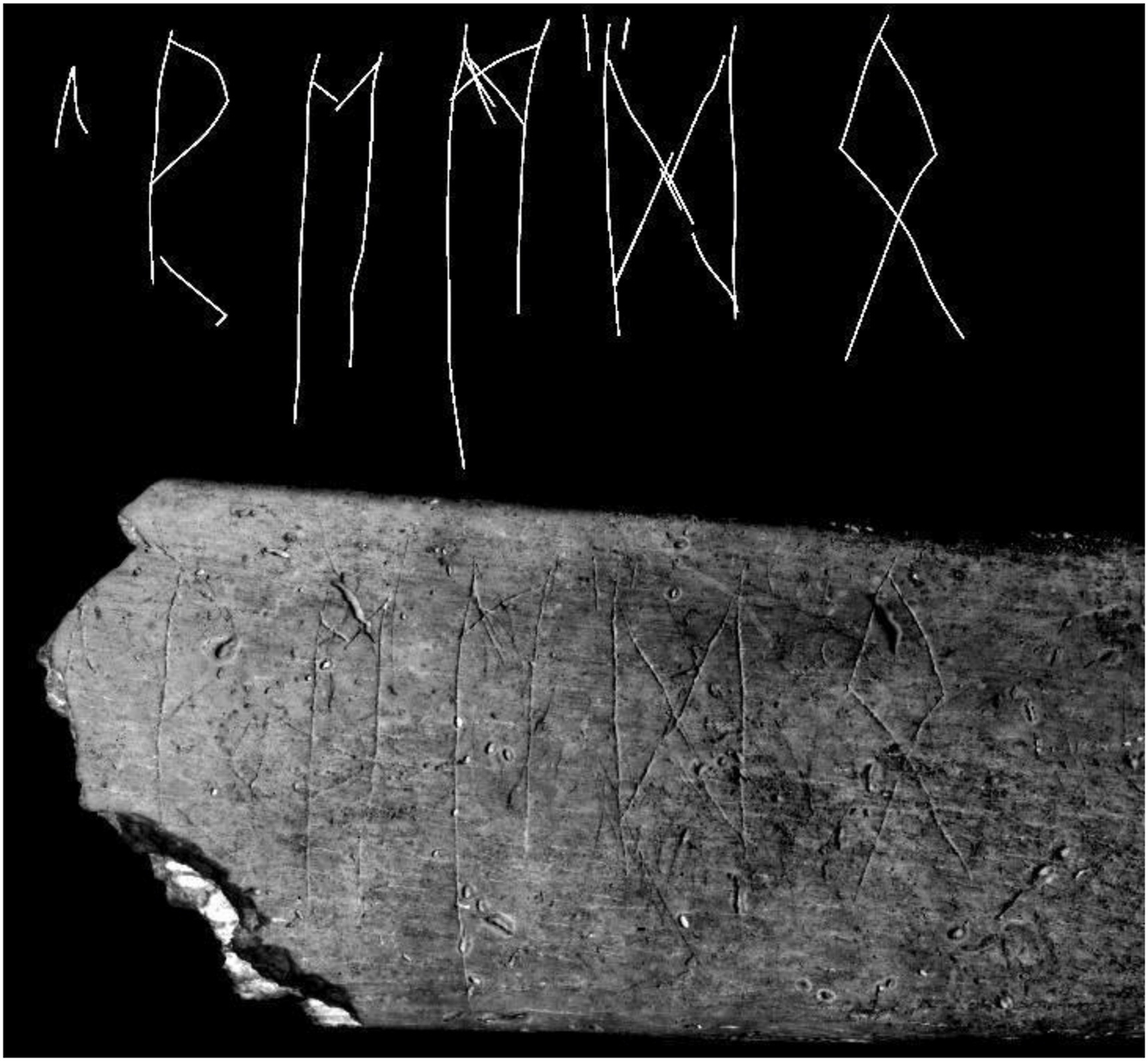

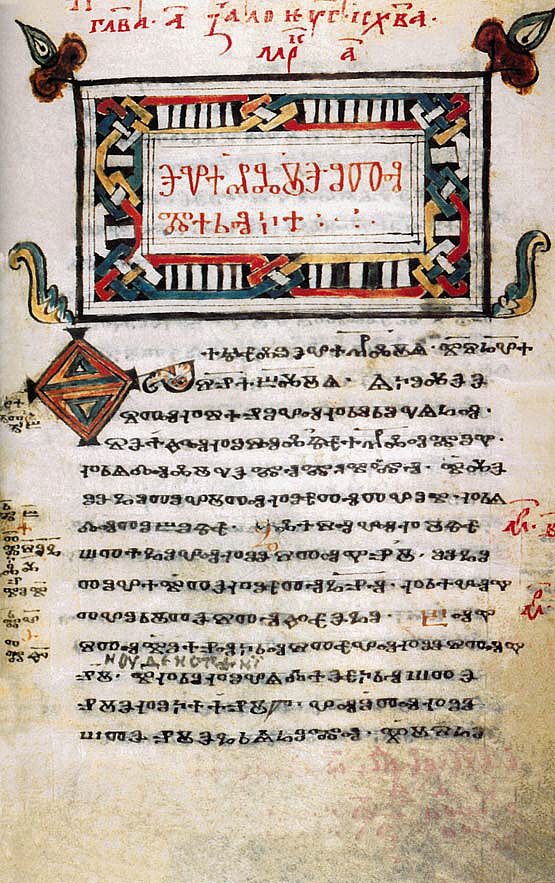

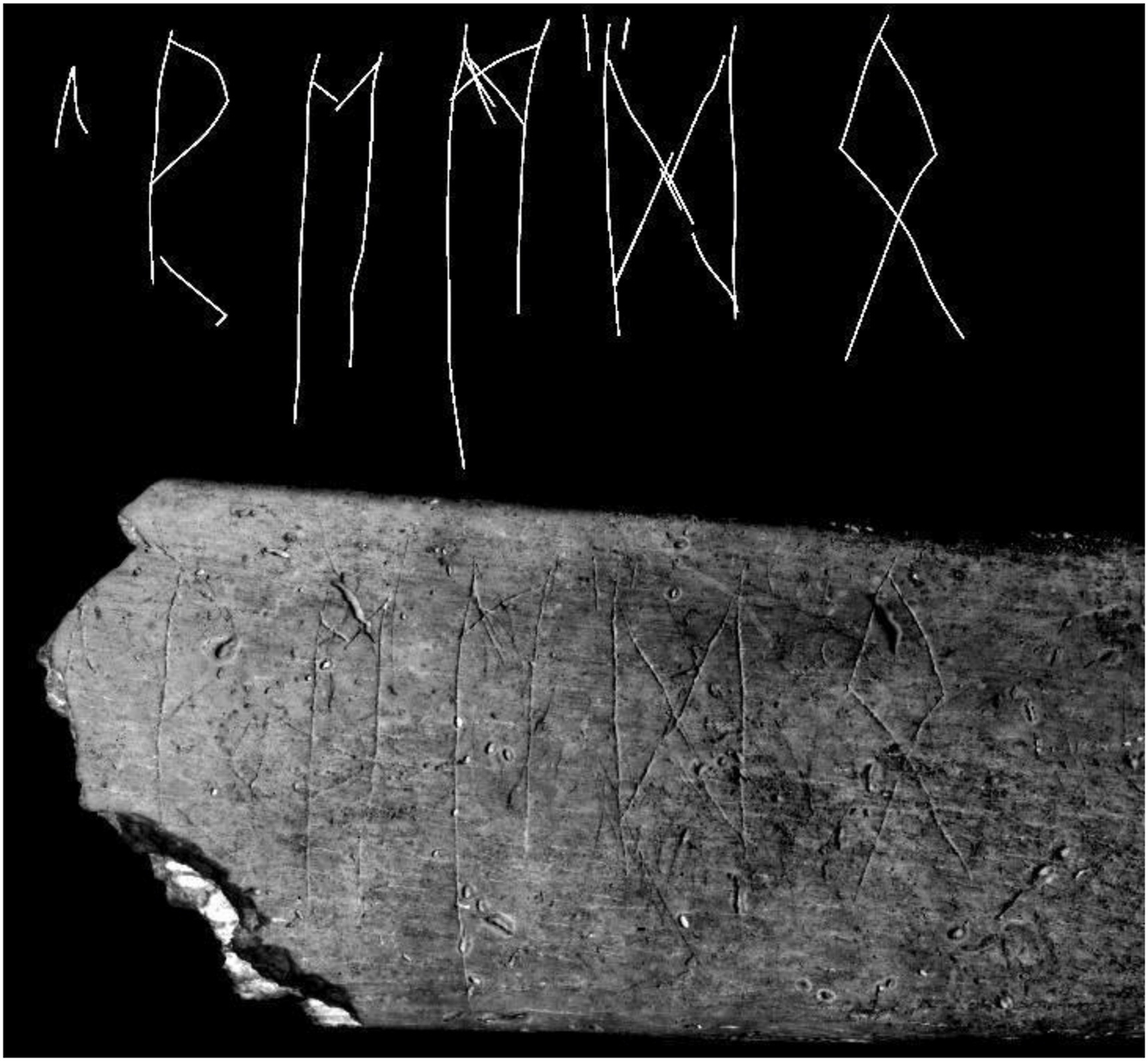

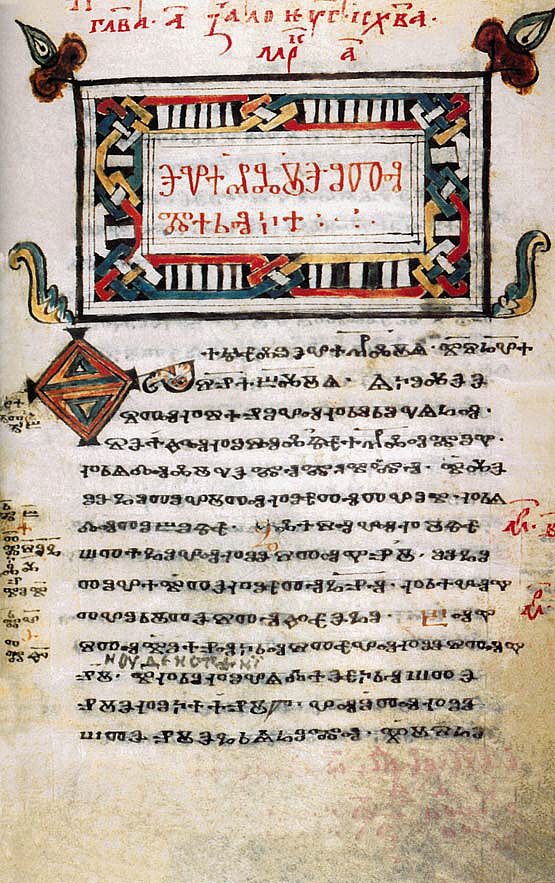

The existence of writing among the Early Slavs is a disputed topic. The Slavs passed down their stories and legends orally like most other tribal peoples in Europe. But in addition to this, a

The existence of writing among the Early Slavs is a disputed topic. The Slavs passed down their stories and legends orally like most other tribal peoples in Europe. But in addition to this, a

The Slavs and

The Slavs and

Little is known about Slavic religion before the

Little is known about Slavic religion before the

Although there is some evidence of early Christianization of the East Slavs, Kievan Rus' either remained largely pagan or relapsed into paganism before the baptism of

Although there is some evidence of early Christianization of the East Slavs, Kievan Rus' either remained largely pagan or relapsed into paganism before the baptism of

tribal societies

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to conflic ...

who lived during the Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roma ...

and the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

(approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries AD) in Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europ ...

and established the foundations for the Slavic nations through the Slavic states of the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

. The Slavs' original homeland is still a matter of debate due to a lack of historical records; however, scholars believe that it was in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

, with Polesia

Polesia, Polesie, or Polesye, uk, Полісся (Polissia), pl, Polesie, russian: Полесье (Polesye) is a natural and historical region that starts from the farthest edge of Central Europe and encompasses Eastern Europe, including East ...

being the most commonly accepted location.

The first written use of the name "Slavs" dates to the 6th century, when the Slavic tribes inhabited a large portion of Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europ ...

. By then, the nomadic Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

-speaking ethnic groups living on the Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistr ...

(the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

, Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

, Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

etc.) had been absorbed by the region's Slavic-speaking population. Over the next two centuries, the Slavs expanded west to the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

river and south towards the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

and the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, absorbing the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

, Germanic, Illyrian and Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

peoples in the process, and also moved east in the direction of the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

.

Beginning in the 7th century, the Slavs were gradually Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

(both Byzantine Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism). By the 12th century, they were the core population of a number of medieval Christian states: East Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert ...

in the Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

, South Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austri ...

in the Bulgarian Empire

In the medieval history of Europe, Bulgaria's status as the Bulgarian Empire ( bg, Българско царство, ''Balgarsko tsarstvo'' ) occurred in two distinct periods: between the seventh and the eleventh centuries and again between the ...

, the Principality of Serbia

The Principality of Serbia ( sr-Cyrl, Књажество Србија, Knjažestvo Srbija) was an autonomous state in the Balkans that came into existence as a result of the Serbian Revolution, which lasted between 1804 and 1817. Its creation wa ...

, the Duchy of Croatia

The Duchy of Croatia (; also Duchy of the Croats, hr , Kneževina Hrvata; ) was a medieval state that was established by White Croats who migrated into the area of the former Roman province of Dalmatia 7th century CE. Throughout its existenc ...

and the Banate of Bosnia

The Banate of Bosnia ( sh, Banovina Bosna / Бановина Босна), or Bosnian Banate (''Bosanska banovina'' / Босанска бановина), was a medieval state based in what is today Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although Hungarian kings ...

, and West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic la ...

in the Principality of Nitra

The Principality of Nitra ( sk, Nitrianske kniežatstvo, Nitriansko, Nitrava, lit=Duchy of Nitra, Nitravia, Nitrava; hu, Nyitrai Fejedelemség), also known as the Duchy of Nitra, was a West Slavic polity encompassing a group of settlements th ...

, Great Moravia

Great Moravia ( la, Regnum Marahensium; el, Μεγάλη Μοραβία, ''Meghálī Moravía''; cz, Velká Morava ; sk, Veľká Morava ; pl, Wielkie Morawy), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to ...

, the Duchy of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia, also later referred to in English as the Czech Duchy, ( cs, České knížectví) was a monarchy and a principality of the Holy Roman Empire in Central Europe during the Early and High Middle Ages. It was formed around 870 b ...

, and the Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exi ...

. The oldest known Slavic principality in history was Carantania

Carantania, also known as Carentania ( sl, Karantanija, german: Karantanien, in Old Slavic '), was a Slavic principality that emerged in the second half of the 7th century, in the territory of present-day southern Austria and north-eastern ...

, established in the 7th century by the Eastern Alpine Slavs, the ancestors of present-day Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, History ...

. Slavic settlement of the Eastern Alps The settlement of the Eastern Alps region by early Slavs took place during the 6th to 8th centuries.

It is part of the southward expansion of the early Slavs which would result in the characterization of the South Slavic group, and would ultimate ...

comprised modern-day Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

, Eastern Friul and large parts of modern-day Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

.

Beginnings

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

writers of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD under the name of Veneti. Authors such as Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

described the Veneti as inhabiting the lands east of the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

river and along the Venedic Bay (Gdańsk Bay

Gdańsk Bay or the Gulf of Gdańsk ( pl, Zatoka Gdańska; csb, Gduńskô Hôwinga; russian: Гданьская бухта, Gdan'skaja bukhta, and german: Danziger Bucht) is a southeastern bay of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the adjacent por ...

). Later, having split into three groups during the migration period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roma ...

, the early Slavs were known to the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

writers as Veneti, Antes and Sclaveni

The ' (in Latin) or ' (various forms in Greek, see below) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became the progenitors of modern South Slavs. They were mentioned by early ...

. The 6th century historian Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') an ...

referred to the Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

(''Sclaveni'') in his 551 work ''Getica

''De origine actibusque Getarum'' (''The Origin and Deeds of the Getae oths'), commonly abbreviated ''Getica'', written in Late Latin by Jordanes in or shortly after 551 AD, claims to be a summary of a voluminous account by Cassiodorus of th ...

'', noting that "although they derive from one nation, now they are known under three names, the Veneti, Antes and Sclaveni" (''ab una stirpe exorti, tria nomina ediderunt, id est Veneti, Antes, Sclaveni'').

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

wrote that "the Sclaveni and the Ante actually had a single name in the remote past; for they were both called Sporoi in olden times". Possibly the oldest mention of Slavs in historical writing ''Slověne'' is attested in Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's ''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

'' (2nd century) as ''Σταυανοί'' (Stavanoi) and ''Σουοβηνοί'' (Souobenoi/Sovobenoi, Suobeni, Suoweni), likely referring to early Slavic tribes in a close alliance with the nomadic Alanians, who may have migrated east of the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

. In the 8th century during the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, early Slavs living on the borders of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the L ...

were referred to as Wends

Wends ( ang, Winedas ; non, Vindar; german: Wenden , ; da, vendere; sv, vender; pl, Wendowie, cz, Wendové) is a historical name for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various people ...

(''Vender''), with the term being a corruption of the earlier Roman-era name.

The earliest, archaeological findings connected to the early Slavs are associated with the Zarubintsy, Przeworsk

Przeworsk (; uk, Переворськ, translit=Perevors'k; yi, פּרשעוואָרסק, translit=Prshevorsk) is a town in south-eastern Poland with 15,675 inhabitants, as of 2 June 2009. Since 1999 it has been in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship ...

and Chernyakhov

The Chernyakhov culture, Cherniakhiv culture or Sântana de Mureș—Chernyakhov culture was an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Ro ...

cultures from around the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. However, in many areas, archaeologists face difficulties in distinguishing between Slavic and non-Slavic findings, as in the case of Przeworsk and Chernyakhov, since the cultures were also attributed to Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

and were not exclusively connected with a single ancient ethnic or linguistic group. Later, beginning in the 6th century, Slavic material cultures included the Prague-Korchak, Penkovka, Ipotești–Cândești, and the Sukow-Dziedzice group cultures. With evidence ranging from fortified settlements ( gords), ceramic pots, weapons, jewellery and open abodes.

Homeland

The Proto-Slavic

The Proto-Slavic homeland

A homeland is a place where a cultural, national, or racial identity has formed. The definition can also mean simply one's country of birth. When used as a proper noun, the Homeland, as well as its equivalents in other languages, often has ethn ...

is the area of Slavic settlement in Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

during the first millennium AD, with its precise location debated by archaeologists, ethnographers and historians. Most scholars consider Polesia

Polesia, Polesie, or Polesye, uk, Полісся (Polissia), pl, Polesie, russian: Полесье (Polesye) is a natural and historical region that starts from the farthest edge of Central Europe and encompasses Eastern Europe, including East ...

the homeland of the Slavs.

Theories attempting to place Slavic origin in the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

have been discarded. None of the proposed homelands reaches the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

in the east, over the Dinaric Alps

The Dinaric Alps (), also Dinarides, are a mountain range in Southern and Southcentral Europe, separating the continental Balkan Peninsula from the Adriatic Sea. They stretch from Italy in the northwest through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herz ...

in the southwest or the Balkan Mountains

The Balkan mountain range (, , known locally also as Stara planina) is a mountain range in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula in Southeastern Europe. The range is conventionally taken to begin at the peak of Vrashka Chuka on the border bet ...

in the south, or past Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

in the west. One of the earliest mention of the Slavs' original homeland is in the Bavarian Geographer The epithet "Bavarian Geographer" ( la, Geographus Bavarus) is the conventional name for the anonymous author of a short Latin medieval text containing a list of the tribes in Central- Eastern Europe, headed ().

The name "Bavarian Geographer" was ...

circa 900, which associates the homeland of the Slavs with the Zeriuani, which some equate to the Cherven lands.

Frederik Kortlandt has suggested that the number of candidates for Slavic homeland may rise from a tendency among historians to date "proto-languages farther back in time than is warranted by the linguistic evidence". Although all spoken languages change gradually over time, the absence of written records allows change to be identified by historians only after a population has expanded and separated long enough to develop daughter languages. The existence of an "original home" is sometimes rejected as arbitrary because the earliest origin sources "always speak of origins and beginnings in a manner which presupposes earlier origins and beginnings".

According to historical records, the Slavic homeland would have been somewhere in Central Europe. The Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

- Penkova- Kolochin complex of cultures of the 6th and the 7th centuries AD is generally accepted to reflect the expansion of Slavic-speakers at the time. Core candidates are cultures within the territories of modern Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

. According to the Polish historian Gerard Labuda, the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introd ...

of Slavic people is the Trzciniec culture

The Trzciniec culture is a Bronze-Age archaeological culture in East-Central Europe (c. 1600 – 1200 BC). It is sometimes associated with the Komariv neighbouring culture, as the Trzciniec-Komariv culture.

History

The Trzciniec culture develop ...

from about 1700 to 1200 BC. The Milograd culture hypothesis posits that the pre-Proto-Slavs (or Balto-Slavs) originated in the 7th century BC–1st century AD culture of northwestern Ukraine and southern Belarus. According to the Chernoles culture theory, the pre-Proto-Slavs originated in the 1025–700 BC culture of northwestern Ukraine and the 3rd century BC–1st century AD Zarubintsy culture

The Zarubintsy or Zarubinets culture was a culture that, from the 3rd century BC until the 1st century AD, flourished in the area north of the Black Sea along the upper and middle Dnieper and Pripyat Rivers, stretching west towards the Souther ...

. According to the Lusatian culture hypothesis, they were present in northeastern Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

in the 1300–500 BC culture and the 2nd century BC–4th century AD Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first artifacts w ...

. The Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

basin hypothesis, postulated by Oleg Trubachyov

Oleg Nikolayevich Trubachyov (also transliterated as Trubachev or Trubačev, russian: Оле́г Никола́евич Трубачёв; 23 October 1930, in Stalingrad – 9 March 2002, in Moscow) was a Soviet and Russian linguist. A re ...

and supported by Florin Curta and ''Nestor's Chronicle

The ''Tale of Bygone Years'' ( orv, Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, translit=Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ; ; ; ; ), often known in English as the ''Rus' Primary Chronicle'', the ''Russian Primary Chronicle'', or simply the ...

'', theorises that the Slavs originated in central and southeastern Europe.

The latest attempt to identify the origin of Slavic language studied the paternal and maternal genetic lineages, as well as autosomal DNA, of all existing modern Slavic populations. Besides confirming their common origin and medieval expansion, the variance and frequency of the Y-DNA haplogroups R1a and I2 subclades R-M558, R-M458, and I-CTS10228 correlate with the medieval spread of Slavic language from Eastern Europe, most probably from the territory of present-day Ukraine (within the area of the middle Dnieper basin) and Southeastern Poland.

Linguistics

Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium B.C. through the 6th ...

began to evolve from Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo ...

, the reconstructed language from which originated a number of languages spoken in Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

. The Slavic languages share a number of features with the Baltic languages

The Baltic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 4.5 million people mainly in areas extending east and southeast of the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. Together with the Slavic lan ...

(including the use of genitive case

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can a ...

for the objects of negative sentences, Proto-Indo-European ''kʷ'' and other labialized velars), which may indicate a common Proto-Balto-Slavic

Proto-Balto-Slavic (PBS or PBSl) is a reconstructed hypothetical proto-language descending from Proto-Indo-European (PIE). From Proto-Balto-Slavic, the later Balto-Slavic languages are thought to have developed, composed of sub-branches Baltic ...

phase in the development of those two linguistic branches of Indo-European. Frederik Kortlandt places the territory of the common language near the Proto-Indo-European homeland

The Proto-Indo-European homeland (or Indo-European homeland) was the prehistoric linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). From this region, its speakers migrated east and west, and went on to form the proto-communities o ...

: "The Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations became speakers of Balto-Slavic

The Balto-Slavic languages form a branch of the Indo-European family of languages, traditionally comprising the Baltic and Slavic languages. Baltic and Slavic languages share several linguistic traits not found in any other Indo-European br ...

". According to the prevailing Kurgan hypothesis

The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory, Kurgan model, or steppe theory) is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and pa ...

, the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans

The Proto-Indo-Europeans are a hypothetical prehistoric population of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the ancestor of the Indo-European languages according to linguistic reconstruction.

Knowledge of them comes chiefly from ...

may have been in the Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian steppe, formed by the Caspian steppe and the Pontic steppe, is the steppeland stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the Pontus Euxinus of antiquity) to the northern area around the Caspian Sea. It extend ...

of eastern Europe. However, "geographical contiguity, parallel development and interaction" may explain the existence of the characteristics of both language groups.

Proto-Slavic developed into a separate language during the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. The Proto-Slavic vocabulary, which was inherited by its daughter languages, described its speakers' physical and social environment, feelings and needs. Proto-Slavic had words for family connections, including ''svekry'' ("husband's mother"), and ''zъly'' ("sister-in-law"). The inherited Common Slavic vocabulary lacks detailed terminology for physical surface features that are peculiar to mountains or the steppe, the sea, coastal features, littoral flora or fauna or saltwater fish.

Proto-Slavic hydronym

A hydronym (from el, ὕδρω, , "water" and , , "name") is a type of toponym that designates a proper name of a body of water. Hydronyms include the proper names of rivers and streams, lakes and ponds, swamps and marshes, seas and oceans. As ...

s have been preserved between the source of the Vistula and the middle basin of the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

. Its northern regions adjoin territory in which river names of Baltic origin (Daugava

, be, Заходняя Дзвіна (), liv, Vēna, et, Väina, german: Düna

, image = Fluss-lv-Düna.png

, image_caption = The drainage basin of the Daugava

, source1_location = Valdai Hills, Russia

, mouth_location = Gulf of Riga, Baltic ...

, Neman

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ; ...

and others) abound. On the south and east, it borders the area of Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

river names (including the Dniester, the Dnieper and the Don). A connection between Proto-Slavic and Iranian languages is also demonstrated by the earliest layer of loanword

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because ...

s in the former; the Proto-Slavic words for god ''(*bogъ)'', demon ''(*divъ)'', house ''(*xata)'', axe ''(*toporъ)'' and dog ''(*sobaka)'' are of Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

origin. The Iranian dialects of the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

and the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

influenced Slavic vocabulary during the millennium of contact between them and early Proto-Slavic.

A longer, more intensive connection between Proto-Slavic and the Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

can be assumed from the number of Germanic loanwords, such as ''*kupiti'' ("to buy"), *xǫdogъ ("beautiful,"), ''*šelmъ'' ("helmet") and ''*xlěvъ'' ("barn"). The Common Slavic words for beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engl ...

, larch

Larches are deciduous conifers in the genus ''Larix'', of the family Pinaceae (subfamily Laricoideae). Growing from tall, they are native to much of the cooler temperate northern hemisphere, on lowlands in the north and high on mountains fur ...

and yew

Yew is a common name given to various species of trees.

It is most prominently given to any of various coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Taxus'':

* European yew or common yew (''Taxus baccata'')

* Pacific yew or western yew (''Taxus br ...

were also borrowed from Germanic, which led Polish botanist Józef Rostafiński to place the Slavic homeland in the Pripet Marshes

__NOTOC__

The Pinsk Marshes ( be, Пінскія балоты, ''Pinskiya baloty''), also known as the Pripet Marshes ( be, Прыпяцкія балоты, ''Prypiackija baloty''), the Polesie Marshes, and the Rokitno Marshes, are a vast natural ...

, which lacks those plants. Germanic languages were a mediator between Common Slavic and other languages; the Proto-Slavic word for emperor ''(*cĕsar'ь)'' was transmitted from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

through a Germanic language, and the Common Slavic word for church ''(*crъky)'' came from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

.

Common Slavic dialects before the 4th century AD cannot be detected since all of the daughter languages emerged from later variants. Tonal word stress (a 9th-century AD change) is present in all Slavic languages, and Proto-Slavic reflects the language that was probably spoken at the end of the 1st millennium AD.

Historiography

Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') an ...

, Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

and other Late Roman

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

authors provide the probable earliest references to the southern Slavs in the second half of the 6th century AD. Jordanes completed his '' Gothic History'', an abridgement of Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

's longer work, in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in 550 or 551. He also used additional sources: books, maps or oral tradition.

Jordanes wrote that the Venethi, Sclavenes and Antes were ethnonyms that referred to the same group. His claim was accepted more than a millennium later by Wawrzyniec Surowiecki, Pavel Jozef Šafárik

Pavel Jozef Šafárik ( sk, Pavol Jozef Šafárik; 13 May 1795 – 26 June 1861) was an ethnic Slovak philologist, poet, literary historian, historian and ethnographer in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was one of the first scientific Slavists.

Family ...

and other historians, who searched the Slavic ''Urheimat

In historical linguistics, the homeland or ''Urheimat'' (, from German '' ur-'' "original" and ''Heimat'', home) of a proto-language is the region in which it was spoken before splitting into different daughter languages. A proto-language is the r ...

'' in the lands that the Venethi (a people named in Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

's ''Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north-c ...

'') lived during the last decades of the 1st century AD. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

wrote that the territory extending from the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

to Aeningia Aeningia is an island mentioned in '' the Natural History'' by Pliny the Elder, written in the 1st century CE. According to Pliny, Aeningia was inhabited by Sarmatians (Sarmati), Veneti (Venedi), Sciri and Hirri, bordering Vistula. Aeningia was pr ...

(probably Feningia, or Finland), was inhabited by the Sarmati, Wends, Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

and Hirri.

Procopius completed his three works on Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

's reign (''Buildings

A building, or edifice, is an enclosed structure with a roof and walls standing more or less permanently in one place, such as a house or factory (although there's also portable buildings). Buildings come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and func ...

'', ''History of the Wars

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent Late antiquity, late antique Greeks, Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Acco ...

'', and ''Secret History

A secret history (or shadow history) is a revisionist interpretation of either fictional or real history which is claimed to have been deliberately suppressed, forgotten, or ignored by established scholars. "Secret history" is also used to desc ...

'') during the 550s. Each book contains detailed information on raids by Sclavenes and Antes on the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantino ...

, and the ''History of the Wars'' has a comprehensive description of their beliefs, customs and dwellings. Although not an eyewitness, Procopius had contacts among the Sclavene mercenaries who were fighting on the Roman side in Italy.

Agreeing with Jordanes's report, Procopius wrote that the Sclavenes and Antes spoke the same languages but traced their common origin not to the Venethi but to a people he called "Sporoi". '' Sporoi'' ("seeds" in Greek; compare "spores") is equivalent to the Latin ''semnones

The Semnones were a Germanic and specifically a Suevian people, who were settled between the Elbe and the Oder in the 1st century when they were described by Tacitus in ''Germania'':

"The Semnones give themselves out to be the most ancient and r ...

'' and ''germani

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

'' ("germs" or "seedlings"), and the German linguist Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law of linguistics, the co-author of t ...

believed that Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

meant "Slav". Jordanes and Procopius called the Suebi "Suavi". The end of the Bavarian Geographer The epithet "Bavarian Geographer" ( la, Geographus Bavarus) is the conventional name for the anonymous author of a short Latin medieval text containing a list of the tribes in Central- Eastern Europe, headed ().

The name "Bavarian Geographer" was ...

's list of Slavic tribes contains a note: "Suevi are not born, they are sown (''seminati'')". The language spoken by Tacitus's Suevi is unknown. In his description of the emigration (c. 512) of the Heruli to Scandinavia, Procopius places the Slavs in Central Europe.

A similar description of the Sclavenes and Antes is found in the ''Strategikon of Maurice

The ''Strategikon'' or ''Strategicon'' ( el, Στρατηγικόν) is a manual of war regarded as written in late antiquity (6th century) and generally attributed to the Byzantine Emperor Maurice.

Overview

The work is a practical manual a ...

'', a military handbook written between 592 and 602 and attributed to Emperor Maurice

Maurice ( la, Mauricius or ''Mauritius''; ; 539 – 27 November 602) was Eastern Roman emperor from 582 to 602 and the last member of the Justinian dynasty. A successful general, Maurice was chosen as heir and son-in-law by his predecessor Tib ...

. Its author, an experienced officer, participated in the Eastern Roman campaigns against the Sclavenes on the lower Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

at the end of the century. A military staff member was also the source of Theophylact Simocatta

Theophylact Simocatta (Byzantine Greek: Θεοφύλακτος Σιμοκάτ(τ)ης ''Theophýlaktos Simokát(t)ēs''; la, Theophylactus Simocatta) was an early seventh-century Byzantine historiographer, arguably ranking as the last historian o ...

's narrative of the same campaigns.

Although Martin of Braga

Martin of Braga (in Latin ''Martinus Bracarensis'', in Portuguese, known as ''Martinho de Dume'' 520–580 AD) was an archbishop of Bracara Augusta in Gallaecia (now Braga in Portugal), a missionary, a monastic founder, and an ecclesiastical ...

was the first western author to refer to a people known as "Sclavus" before 580, Jonas of Bobbio

Jonas of Bobbio (also known as Jonas of Susa) (Sigusia, now Susa, Italy, 600 – after 659 AD) was a Columbanian monk and a major Latin monastic author of hagiography. His ''Life of Saint Columbanus'' is "one of the most influential works of ...

included the earliest lengthy record of the nearby Slavs in his ''Life of Saint Columbanus'' (written between 639 and 643). Jonas referred to the Slavs as "Veneti" and noted that they were also known as "Sclavi".

Western authors, including Fredegar

The ''Chronicle of Fredegar'' is the conventional title used for a 7th-century Frankish chronicle that was probably written in Burgundy. The author is unknown and the attribution to Fredegar dates only from the 16th century.

The chronicle begin ...

and Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations o ...

, preserved the term "Venethi". The Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

(in the ''Life of Saint Martinus'', the ''Chronicle of Fredegar

The ''Chronicle of Fredegar'' is the conventional title used for a 7th-century Frankish chronicle that was probably written in Burgundy. The author is unknown and the attribution to Fredegar dates only from the 16th century.

The chronicle begin ...

'' and Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Floren ...

), Lombards (Paul the Deacon

Paul the Deacon ( 720s 13 April in 796, 797, 798, or 799 AD), also known as ''Paulus Diaconus'', ''Warnefridus'', ''Barnefridus'', or ''Winfridus'', and sometimes suffixed ''Cassinensis'' (''i.e.'' "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, ...

) and Anglo-Saxons (''Widsith

"Widsith" ( ang, Wīdsīþ, "far-traveller", lit. "wide-journey"), also known as "The Traveller's Song", is an Old English poem of 143 lines. It survives only in the '' Exeter Book'', a manuscript of Old English poetry compiled in the late-10th ...

'') referred to Slavs in the Elbe-Saale region and Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

as "Wenden" or "Winden" (see Wends

Wends ( ang, Winedas ; non, Vindar; german: Wenden , ; da, vendere; sv, vender; pl, Wendowie, cz, Wendové) is a historical name for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various people ...

). The Franks and the Bavarians of Styria and Carinthia called their Slavic neighbours "Windische".

The unknown author of the ''Chronicle of Fredegar'' used the word "Venedi" (and variants) to refer to a group of Slavs who were subjugated by the Avars. In the chronicle, "Venedi" formed a state that emerged from a revolt led by the Frankish merchant Samo

Samo (–) founded the first recorded political union of Slavic tribes, known as Samo's Empire (''realm'', ''kingdom'', or ''tribal union''), stretching from Silesia to present-day Slovakia, ruling from 623 until his death in 658. According to ...

against the Avars around 623. A change in terminology, the replacement of Slavic tribal names for the collective "Sclavenes" and "Antes", occurred at the end of the century; the first tribal names were recorded in the second book of the ''Miracles of Saint Demetrius

The ''Miracles of Saint Demetrius'' ( la, Miracula Sancti Demetrii) is a 7th-century collection of homilies, written in Greek, accounting the miracles performed by the patron saint of Thessalonica, Saint Demetrius. It is a unique work for the ...

'', around 690. The unknown "Bavarian Geographer" listed Slavic tribes in the Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

around 840, and a detailed description of 10th-century tribes in the Balkan Peninsula was compiled under the auspices of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe ...

in Constantinople around 950.

Archaeology

In the archaeological literature, attempts have been made to assign an early Slavic character to several cultures in a number of time periods and regions. The Prague-Korchak cultural horizon encompasses postulated early Slavic cultures from the Elbe to the Dniester, in contrast with the Dniester-to-Dnieper Prague-Penkovka. "Prague culture" in a narrow sense, refers to western Slavic material grouped around Bohemia, Moravia and western Slovakia, distinct from the Mogilla (southern Poland) and Korchak (central Ukraine and southern Belarus) groups further east. The Prague and Mogilla groups are seen as the archaeological reflection of the 6th-century Western Slavs.

The 2nd-to-5th-century

In the archaeological literature, attempts have been made to assign an early Slavic character to several cultures in a number of time periods and regions. The Prague-Korchak cultural horizon encompasses postulated early Slavic cultures from the Elbe to the Dniester, in contrast with the Dniester-to-Dnieper Prague-Penkovka. "Prague culture" in a narrow sense, refers to western Slavic material grouped around Bohemia, Moravia and western Slovakia, distinct from the Mogilla (southern Poland) and Korchak (central Ukraine and southern Belarus) groups further east. The Prague and Mogilla groups are seen as the archaeological reflection of the 6th-century Western Slavs.

The 2nd-to-5th-century Chernyakhov culture

The Chernyakhov culture, Cherniakhiv culture or Sântana de Mureș—Chernyakhov culture was an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Rom ...

encompassed modern Ukraine, Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnistri ...

and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

. Chernyakov finds include polished black-pottery vessels, fine metal ornaments and iron tools. Soviet scholars, such as Boris Rybakov

Boris Alexandrovich Rybakov (Russian: Бори́с Алекса́ндрович Рыбако́в, 3 June 1908, Moscow – 27 December 2001) was a Soviet and Russian historian who personified the anti-Normanist vision of Russian history. He is th ...

, saw it as the archaeological reflection of the proto-Slavs. The Chernyakov zone is now seen as representing the cultural interaction of several peoples, one of which was rooted in Scytho-Sarmatian traditions, which were modified by Germanic elements that were introduced by the Goths. The semi-subterranean dwelling with a corner hearth later became typical of early Slavic sites, with Volodymir Baran calling it a Slavic "ethnic badge". In the Carpathian

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretches ...

foothills of Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-centra ...

, at the northwestern fringes of the Chernyakov zone, the Slavs gradually became a culturally-unified people; the multiethnic environment of the Chernyakhov zone presented a "need for self-identification

In the psychology of self, one's self-concept (also called self-construction, self-identity, self-perspective or self-structure) is a collection of beliefs about oneself. Generally, self-concept embodies the answer to the question ''"Who am I? ...

in order to manifest their differentiation from other groups".

The Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first artifacts w ...

, northwest of the Chernyakov zone, extended from the Dniester to the Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. Once, it was called "the most Hungarian river" because it flowed entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

The Tisza be ...

valley and north to the Vistula and Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

. It was an amalgam of local cultures, most with roots in earlier traditions modified by influences from the (Celtic) La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defi ...

, (Germanic) Jastorf culture

The Jastorf culture was an Iron Age material culture in what is now northern Germany and southern Scandinavia spanning the 6th to 1st centuries BC, forming part of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and associating with Germanic peoples. The culture evo ...

beyond the Oder and the Bell-Grave culture of the Polish plain. The Venethi may have played a part; other groups included the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, Burgundians

The Burgundians ( la, Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; on, Burgundar; ang, Burgendas; grc-gre, Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and ...

and Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

. East of the Przeworsk zone was the Zarubinets culture, which is sometimes considered part of the Przeworsk complex. Early Slavic hydronyms are found in the area occupied by the Zarubinets culture, and Irena Rusinova proposed that the most prototypical examples of Prague-type pottery later originated there. The Zarubinets culture is identified as proto-Slavic or an ethnically mixed community that became Slavicized.

With increasing age, the confidence with which archaeological connections can be made to known historic groups lessens. The Chernoles culture has been seen as a stage in the evolution of the Slavs, and Marija Gimbutas

Marija Gimbutas ( lt, Marija Gimbutienė, ; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994) was a Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist known for her research into the Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of " Old Europe" and for her Kurgan hypothesis ...

identified it as the proto-Slavic homeland. According to many pre-historians, ethnic labels are inappropriate for European Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

peoples.

The Globular Amphora culture

The Globular Amphora culture (GAC, (KAK); ), c. 3400–2800 BC, is an archaeological culture in Central Europe. Marija Gimbutas assumed an Indo-European origin, though this is contradicted by newer genetic studies that show a connection to the ear ...

stretched from the middle Dnieper to the Elbe during the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BC. It has been suggested as the locus of a Germano-Balto-Slavic continuum (the Germanic substrate hypothesis), but the identification of its bearers as Indo-Europeans is uncertain. The area of the culture contains a number of tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones built ...

, which are typical of Indo-Europeans.

The 8th-to-3rd-century BC Chernoles culture, sometimes associated with Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

' "Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

farmers", is "sometimes portrayed as either a state in the development of the Slavic languages or at least some form of late Indo-European ancestral to the evolution of the Slavic stock". The Milograd culture (700 BC–100 AD), centred roughly in today's Belarus and north of the Chernoles culture, has also been proposed as ancestral for the Slavs or the Balts

The Balts or Baltic peoples ( lt, baltai, lv, balti) are an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak the Baltic languages of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages.

One of the features of Baltic languages is the number ...

. The ethnic composition of the Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first artifacts w ...

(2nd century BC to 4th century AD), associated with the Lugii

The Lugii (or ''Lugi'', ''Lygii'', ''Ligii'', ''Lugiones'', ''Lygians'', ''Ligians'', ''Lugians'', or ''Lougoi'') were a large tribal confederation mentioned by Roman authors living in ca. 100 BC–300 AD in Central Europe, north of the Sude ...

) of central and southern Poland, northern Slovakia and Ukraine, including the Zarubintsy culture

The Zarubintsy or Zarubinets culture was a culture that, from the 3rd century BC until the 1st century AD, flourished in the area north of the Black Sea along the upper and middle Dnieper and Pripyat Rivers, stretching west towards the Souther ...

(2nd century BC to 2nd century AD and connected with the Bastarnae

The Bastarnae ( Latin variants: ''Bastarni'', or ''Basternae''; grc, Βαστάρναι or Βαστέρναι) and Peucini ( grc, Πευκῖνοι) were two ancient peoples who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited areas north of the Roman front ...

tribe) and the Oksywie culture

The Oksywie culture (German ') was an archaeological culture that existed in the area of modern-day Eastern Pomerania around the lower Vistula river from the 2nd century BC to the early 1st century AD. It is named after the village of Oksywie, ...

are other candidates.

Southern Ukraine

Southern Ukraine ( uk, південна Україна, translit=pivdenna Ukrayina) or south Ukraine refers, generally, to the oblasts in the south of Ukraine.

The territory usually corresponds with the Soviet economical district, the Southern ...

is known to have been inhabited by Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

and Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

tribes before the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

. Early Slavic stone stelae that are found in the middle Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and t ...

region are markedly different from the Scythian and Sarmatian stelae of the Crimea.

The Wielbark culture

The Wielbark culture (german: Wielbark-Willenberg-Kultur; pl, Kultura wielbarska) or East Pomeranian-Mazovian is an Iron Age archaeological complex which flourished on the territory of today's Poland from the 1st century AD to the 5th century AD. ...

displaced the eastern Oksywie culture

The Oksywie culture (German ') was an archaeological culture that existed in the area of modern-day Eastern Pomerania around the lower Vistula river from the 2nd century BC to the early 1st century AD. It is named after the village of Oksywie, ...

during the 1st century AD. Although the 2nd-to-5th-century Chernyakhov culture

The Chernyakhov culture, Cherniakhiv culture or Sântana de Mureș—Chernyakhov culture was an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Rom ...

triggered the decline of the late Sarmatian culture from the 2nd to the 4th centuries, the western part of the Przeworsk culture remained intact until the 4th century and the Kiev culture flourished from the 2nd to the 5th centuries and is recognised as the predecessor of the 6th- and 7th-century Prague-Korchak and Pen'kovo cultures, the first archaeological cultures that are identified as Slavic. Although Proto-Slavic probably reached its final stage in the Kiev area, the scientific community disagrees on the Kiev culture's predecessors. Some scholars trace them from the Ruthenian Milograd culture, others from the Ukrainian Chernoles and Zarubintsy cultures and still others from the Polish Przeworsk culture.

Ethnogenesis