Ancient Egypt technology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ancient Egyptian technology describes devices and technologies invented or used in Ancient Egypt. The

The word ''paper'' comes from the Greek term for the ancient Egyptian

The word ''paper'' comes from the Greek term for the ancient Egyptian

The most famous

The most famous

File:Wells egyptian ship red sea.png, Egyptian ship, 1250 BC Egyptian ship on the Red Sea, showing a board truss being used to stiffen the beam of this ship

File:Illustrerad Verldshistoria band I Ill 008.jpg, Egyptian ship with a loose-footed sail, similar to a

The ancient Egyptians had experience with building a variety of ships. Some of them survive to this day as

and remnants of other ships were found near the pyramids. Sneferu's ancient cedar wood ship Praise of the Two Lands is the first reference recorded to a ship being referred to by name.Anzovin, item # 5393, page 385 ''Reference to a ship with a name appears in an inscription of 2613 BCE that recounts the shipbuilding achievements of the fourth-dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Sneferu. He was recorded as the builder of a cedarwood vessel called "Praise of the Two Lands."'' Although quarter rudders were the norm in Nile navigation, the Egyptians were the first to use also stern-mounted rudders (not of the modern type but center mounted steering oars). The first warships of Ancient Egypt were constructed during the early Middle Kingdom and perhaps at the end of the According to the Greek historian

According to the Greek historian

The earliest known

The earliest known

Claims have been made that

Claims have been made that

The

The

According to a paper published by Michael D. Parkins, 72% of 260 medical prescriptions in the Hearst papyrus had no curative elements. According to Michael D. Parkins, sewage pharmacology first began in ancient Egypt and was continued through the Middle Ages, and while the use of animal dung can have curative properties, it is not without its risk. Practices such as applying cow dung to wounds, ear piercing, tattooing, and chronic ear infections were important factors in developing

Some have suggested that the Egyptians had some form of understanding

Some have suggested that the Egyptians had some form of understanding

Online article

* Institutt for Arkeologi, Kunsthistorie og Konservering website, in English a

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ancient Egyptian Technology

Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

invented and used many simple machines

A simple machine is a mechanical device that changes the direction or magnitude of a force. In general, they can be defined as the simplest mechanisms that use mechanical advantage (also called leverage) to multiply force. Usually the term ref ...

, such as the ramp

An inclined plane, also known as a ramp, is a flat supporting surface tilted at an angle from the vertical direction, with one end higher than the other, used as an aid for raising or lowering a load. The inclined plane is one of the six clas ...

and the lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

, to aid construction processes. They used rope

A rope is a group of yarns, plies, fibres, or strands that are twisted or braided together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have tensile strength and so can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger than similarl ...

truss

A truss is an assembly of ''members'' such as beams, connected by ''nodes'', that creates a rigid structure.

In engineering, a truss is a structure that "consists of two-force members only, where the members are organized so that the assembl ...

es to stiffen the beam of ships. Egyptian paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distribu ...

, made from papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to ...

, and pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

were mass-produced and exported throughout the Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

. The wheel

A wheel is a circular component that is intended to rotate on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction with axles, allow heavy objects to be ...

was used for a number of purposes, but chariots

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nbs ...

only came into use after the Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when ancient Egypt fell into disarray for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a "Second Intermediate Period" was coined in 1942 b ...

. The Egyptians also played an important role in developing Mediterranean maritime

Maritime may refer to:

Geography

* Maritime Alps, a mountain range in the southwestern part of the Alps

* Maritime Region, a region in Togo

* Maritime Southeast Asia

* The Maritimes, the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Pri ...

technology including ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

s and lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses m ...

s.

Technology in Dynastic Egypt

Significant advances in ancient Egypt during the dynastic period includeastronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

. Their geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

was a necessary outgrowth of surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

to preserve the layout and ownership of fertile farmland, which was flooded annually by the Nile River

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

. The 3,4,5 right triangle

A right triangle (American English) or right-angled triangle ( British), or more formally an orthogonal triangle, formerly called a rectangled triangle ( grc, ὀρθόσγωνία, lit=upright angle), is a triangle in which one angle is a right a ...

and other rules of thumb served to represent rectilinear structures, and the post and lintel architecture of Egypt. Egypt also was a center of alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wo ...

research for much of the western world.

Paper, writing and libraries

The word ''paper'' comes from the Greek term for the ancient Egyptian

The word ''paper'' comes from the Greek term for the ancient Egyptian writing material

Writing material refers to the materials that provide the surfaces on which humans use writing instruments to inscribe writings. The same materials can also be used for symbolic or representational drawings. Building material on which writings or ...

called papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to ...

, which was formed from beaten strips of papyrus plants. Papyrus was produced in Egypt as early as 3000 BC and was sold to ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. The establishment of the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, t ...

limited the supply of papyrus for others. According to the Roman historian Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

('' Natural History'' records, xiii.21), as a result of this, parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins ...

was invented under the patronage of Eumenes II of Pergamon to build his rival library at Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

. However, this is a myth; parchment had been in use in Anatolia and elsewhere long before the rise of Pergamon.

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

, a phonetic

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

writing system

A writing system is a method of visually representing verbal communication, based on a script and a set of rules regulating its use. While both writing and speech are useful in conveying messages, writing differs in also being a reliable fo ...

, served as the basis for the Phoenician alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet (more specifically, an abjad) known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

The Phoenician al ...

from which later alphabets, such as Hebrew, Greek, and Latin were derived. With this ability, writing and record-keeping, the Egyptians developed one of the – if not ''the'' – first decimal system.

The city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

retained preeminence for its records and scrolls with its library. This ancient library was damaged by fire when it fell under Roman rule,Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, ''Life of Caesar'' 49.3. and was destroyed completely by 642 CE. With it, a vast supply of antique literature, history, and knowledge was lost.

Structures and construction

Materials and tools

Some of the older materials used in the construction of Egyptian housing included reeds and clay. According to Lucas and Harris, "reeds were plastered with clay in order to keep out of heat and cold more effectually". Tools that were used were "limestone, chiseled stones, wooden mallets, and stone hammers". With these tools, ancient Egyptians were able to create more than just housing, but also sculptures of their gods.Buildings

Many Egyptian temples are not standing today. Some are in ruin from wear and tear, while others have been lost entirely. The Egyptian structures are among the largest constructions ever conceived and built by humans. They constitute one of the most potent and enduring symbols of ancient Egyptian civilization. Temples and tombs built by a pharaoh famous for her projects,Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

, were massive and included many colossal statues of her. Pharaoh Tutankamun's rock-cut tomb

A tomb ( grc-gre, τύμβος ''tumbos'') is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes. Placing a corpse into a tomb can be called ''immureme ...

in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings ( ar, وادي الملوك ; Late Coptic: ), also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings ( ar, وادي أبوا الملوك ), is a valley in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th ...

was full of jewelry and antiques. In some late myths, Ptah

Ptah ( egy, ptḥ, reconstructed ; grc, Φθά; cop, ⲡⲧⲁϩ; Phoenician: 𐤐𐤕𐤇, romanized: ptḥ) is an ancient Egyptian deity, a creator god and patron deity of craftsmen and architects. In the triad of Memphis, he is the hu ...

was identified as the primordial mound and had called creation into being, he was considered the deity of craftsmen, and in particular, of stone-based crafts. Imhotep

Imhotep (; egy, ỉỉ-m-ḥtp "(the one who) comes in peace"; fl. late 27th century BCE) was an Egyptian chancellor to the Pharaoh Djoser, possible architect of Djoser's step pyramid, and high priest of the sun god Ra at Heliopol ...

, who was included in the Egyptian pantheon

Ancient Egyptian deities are the gods and goddesses worshipped in ancient Egypt. The beliefs and rituals surrounding these gods formed the core of ancient Egyptian religion, which emerged sometime in prehistory. Deities represented natural f ...

, was the first documented engineer.

In Hellenistic Egypt, lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses m ...

technology was developed, the most famous example being the Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria (; Ancient Greek: ὁ Φάρος τῆς Ἀλεξανδρείας, contemporary Koine ), was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, during the rei ...

. Alexandria was a port for the ships that traded the goods manufactured in Egypt or imported into Egypt. A giant cantilevered hoist lifted cargo to and from ships. The lighthouse itself was designed by Sostratus of Cnidus and built in the 3rd century BC (between 285 and 247 BC) on the island of Pharos in Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, which has since become a peninsula. This lighthouse was renowned in its time and knowledge of it was never lost.

Monuments

The Nile valley has been the site of one of the most influentialcivilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

s in the world with its architectural monuments, which include the Giza pyramid complex

The Giza pyramid complex ( ar, مجمع أهرامات الجيزة), also called the Giza necropolis, is the site on the Giza Plateau in Greater Cairo, Egypt that includes the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Me ...

and the Great Sphinx

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a limestone statue of a reclining sphinx, a mythical creature with the head of a human, and the body of a lion. Facing directly from west to east, it stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, E ...

.

The most famous

The most famous pyramid

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilate ...

s are the Egyptian pyramids

The Egyptian pyramids are ancient masonry structures located in Egypt. Sources cite at least 118 identified "Egyptian" pyramids. Approximately 80 pyramids were built within the Kingdom of Kush, now located in the modern country of Sudan. Of ...

—huge structures built of brick or stone, some of which are among the largest constructions by humans. Pyramids functioned as tomb

A tomb ( grc-gre, τύμβος ''tumbos'') is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes. Placing a corpse into a tomb can be called ''immureme ...

s for pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

s. In Ancient Egypt, a pyramid was referred to as ''mer'', literally "place of ascendance." The Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient Worl ...

is the largest in Egypt and one of the largest in the world. The base is over in area. It is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2 ...

and the only one of the seven to survive into modern times. The ancient Egyptians capped the peaks of their pyramids with gold plated pyramidions and covered their faces with polished white limestone, although many of the stones used for the finishing purpose have fallen or been removed for use on other structures over the millennia.

The Red Pyramid

The Red Pyramid, also called the North Pyramid, is the largest of the pyramids located at the Dahshur necropolis in Cairo, Egypt. Named for the rusty reddish hue of its red limestone stones, it is also the third largest Egyptian pyramid, after t ...

(c.26th century BC), named for the light crimson hue of its exposed granite surfaces, is the third largest of Egyptian pyramids. Menkaure's Pyramid

The pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest of the three main pyramids of the Giza pyramid complex, located on the Giza Plateau in the southwestern outskirts of Cairo, Egypt. It is thought to have been built to serve as the tomb of the Fourth Dynasty ...

, likely dating to the same era, was constructed of limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

and granite blocks. The Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient Worl ...

(c. 2580 BC) contains a huge sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

fashioned of red Aswan

Aswan (, also ; ar, أسوان, ʾAswān ; cop, Ⲥⲟⲩⲁⲛ ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of the ...

granite. The mostly ruined Black Pyramid

The Black Pyramid ( ar, الهرم الأسود, al-Haram al'Aswad) was built by King Amenemhat III (r. c. 1860 BC-c. 1814 BC) during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2055–1650 BC). It is one of the five remaining pyramids of the original eleven ...

dating from the reign of Amenemhat III

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat III ( Ancient Egyptian: ''Ỉmn-m-hꜣt'' meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet III, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the sixth king of the Twelfth D ...

once had a polished granite pyramidion or capstone, now on display in the main hall of the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, known commonly as the Egyptian Museum or the Cairo Museum, in Cairo, Egypt, is home to an extensive collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities. It has 120,000 items, with a representative amount on display a ...

in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

. Other uses in Ancient Egypt include column

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression (physical), compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column i ...

s, door lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented structural item. In the case of ...

s, sill

Sill may refer to:

* Sill (dock), a weir at the low water mark retaining water within a dock

* Sill (geology), a subhorizontal sheet intrusion of molten or solidified magma

* Sill (geostatistics)

* Sill (river), a river in Austria

* Sill plate, ...

s, jamb

A jamb (from French ''jambe'', "leg"), in architecture, is the side-post or lining of a doorway or other aperture. The jambs of a window outside the frame are called “reveals.” Small shafts to doors and windows with caps and bases are known ...

s, and wall and floor veneer.

The ancient Egyptians had some of the first monumental stone buildings (such as in Saqqara

Saqqara ( ar, سقارة, ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memph ...

). How the Egyptians worked the solid granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

is still a matter of debate. Archaeologist Patrick Hunt has postulated that the Egyptians used emery shown to have higher hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardness; for example hard ...

on the Mohs scale

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness () is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material.

The scale was introduced in 1812 by ...

. Regarding construction, of the various methods possibly used by builders, the lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

moved and uplifted obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

s weighing more than 100 tons

Tons can refer to:

* Tons River, a major river in India

* Tamsa River, locally called Tons in its lower parts (Allahabad district, Uttar pradesh, India).

* the plural of ton, a unit of mass, force, volume, energy or power

:* short ton, 2,000 poun ...

.

Obelisks and pillars

Obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

s were a prominent part of the Ancient Egyptian architecture

Spanning over three thousand years, ancient Egypt was not one stable civilization but in constant change and upheaval, commonly split into periods by historians. Likewise, ancient Egyptian architecture is not one style, but a set of styles diff ...

, placed in pairs at the entrances of various monuments and important buildings such as temples. In 1902, ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' wrote: "The earliest temple obelisk still in position is that of Senusret I

Senusret I (Middle Egyptian: z-n-wsrt; /suʀ nij ˈwas.ɾiʔ/) also anglicized as Sesostris I and Senwosret I, was the second pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1971 BC to 1926 BC (1920 BC to 1875 BC), and was one of the mos ...

of the XIIth Dynasty at Heliopolis (68 feet high)". The word ''obelisk'' is of Greek rather than Egyptian origin because Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, the great traveler, was the first writer to describe the objects. Twenty-nine ancient Egyptian obelisks are known to have survived, plus the Unfinished obelisk being built by Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

to celebrate her sixteenth year as pharaoh. It broke while being carved out of the quarry and was abandoned when another one was begun to replace it. The broken one was found at Aswan and provides some of the only insight into the methods of how they were hewn.

The obelisk symbolized the sky deity Ra and during the brief religious reformation of Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth D ...

was said to be a petrified ray of the Aten

Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn ( egy, jtn, ''reconstructed'' ) was the focus of Atenism, the religious system established in ancient Egypt by the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. The Aten was the disc of the sun and originally an aspect o ...

, the sun disk. It is hypothesized by New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

Egyptologist

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , '' -logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religiou ...

Patricia Blackwell Gary and ''Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

'' senior editor Richard Talcott that the shapes of the ancient Egyptian pyramid and obelisk were derived from natural phenomena associated with the sun (the sun-god Ra being the Egyptians' greatest deity). It was also thought that the deity existed within the structure. The Egyptians also used pillar

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member. ...

s extensively.

It is unknown whether the ancient Egyptians had kite

A kite is a tethered heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create lift and drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have a bridle and tail to guide the fac ...

s, but a team led by Maureen Clemmons and Mory Gharib raised a 5,900-pound, obelisk into vertical position with a kite, a system of pulleys, and a support frame. Maureen Clemmons developed the idea that the ancient Egyptians used kites for work.

Ramps have been reported as being widely used in Ancient Egypt. A ramp is an inclined plane, or a plane surface set at an angle (other than a right angle) against a horizontal surface. The inclined plane permits one to overcome a large resistance by applying a relatively small force through a longer distance than the load is to be raised. In civil engineering the slope (ratio of rise/run) is often referred to as a grade or gradient. An inclined plane is one of the commonly-recognized simple machines. Maureen Clemmons subsequently led a team of researchers demonstrating a kite made of natural material and reinforced with shellac (which according to their research pulled with 97% the efficiency of nylon), in a 9 mph wind, would easily pull an average 2-ton pyramid stone up the 1st two courses of a pyramid (in collaboration with Cal Poly, Pomona, on a 53-stone pyramid built in Rosamond, CA).

Navigation and ship building

The ancient Egyptians had knowledge to some extent ofsail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails ma ...

construction. This is governed by the science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

of aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

. The earliest Egyptian sails were simply placed to catch the wind and push a vessel.Encyclopedia Of International Sports Studies. Page 31 Later Egyptian sails dating to 2400 BC were built with the recognition that ships could sail against the wind using the lift of the sails. Queen Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

oversaw the preparations and funding of an expedition of five ships, each measuring seventy feet long, and ''with several sails''.Various others exist, also.

longship

Longships were a type of specialised Scandinavian warships that have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by the Nor ...

. From the 5th dynasty (around 2700 BC)

File:Antico regno, modello di nave, da saqqara, 01.JPG, Model ship from the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

(2686–2181 BC)

File:Maler der Grabkammer des Menna 013.jpg, Stern-mounted steering oar of an Egyptian riverboat depicted in the Tomb of Menna

The ancient Egyptian official named Menna carried a number of titles associated with the agricultural estates of the temple of Karnak and the king. Information about Menna comes primarily from his richly decorated tomb (TT69, TT 69) in the necrop ...

(c. 1422–1411 BC) Note that the sail is stretched between yards.

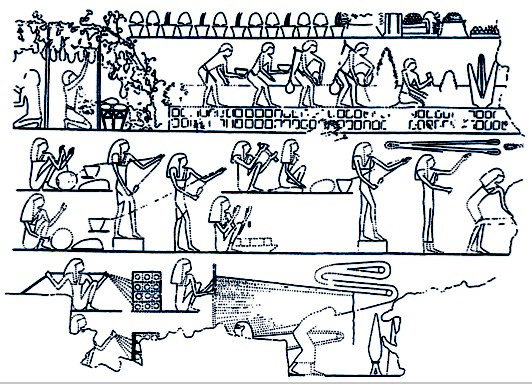

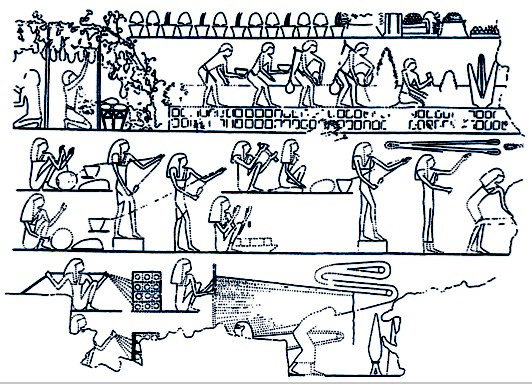

File:Die Gartenlaube (1886) b 796 1.jpg, Loading Egyptian vessels with the produce of Punt. Shows folded sails, lowered upper yard, yard construction, and heavy deck cargo.

Khufu ship

The Khufu ship is an intact full-size solar barque from ancient Egypt. It was sealed into a pit at the foot of the Great Pyramid of pharaoh Khufu around 2500 BC, during the Fourth Dynasty of the ancient Egyptian Old Kingdom. Like other buried ...

. The ships were found in many areas of Egypt as the Abydos boats

The Abydos boats are the remnants of a group of ancient royal Egyptian ceremonial boats found at an archaeological site in Abydos, Egypt. Discovered in 1991, excavation of the Abydos boats began in 2000 at which time fourteen boats were identified ...

Sakkara and Abydous Ship Gravesand remnants of other ships were found near the pyramids. Sneferu's ancient cedar wood ship Praise of the Two Lands is the first reference recorded to a ship being referred to by name.Anzovin, item # 5393, page 385 ''Reference to a ship with a name appears in an inscription of 2613 BCE that recounts the shipbuilding achievements of the fourth-dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Sneferu. He was recorded as the builder of a cedarwood vessel called "Praise of the Two Lands."'' Although quarter rudders were the norm in Nile navigation, the Egyptians were the first to use also stern-mounted rudders (not of the modern type but center mounted steering oars). The first warships of Ancient Egypt were constructed during the early Middle Kingdom and perhaps at the end of the

Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

, but the first mention and a detailed description of a large enough and heavily armed ship dates from 16th century BC.

When Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 2 ...

achieved warships displacement up to 360 tons and carried up to ten new heavy and light to seventeen catapults based bronze springs, called "siege crossbow" – more precisely, siege bows. Still appeared giant catamarans that are heavy warships and times of Ramesses III

Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses III (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty in Ancient Egypt. He is thought to have reigned from 26 March 1186 to 15 April 1155 BC and is considered to be the last great mona ...

used even when the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; grc, Πτολεμαῖοι, ''Ptolemaioi''), sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty (Λαγίδαι, ''Lagidae;'' after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic ...

.

According to the Greek historian

According to the Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, Necho II sent out an expedition of Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

, which reputedly, at some point between 610 and before 594 BC, sailed in three years from the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

around Africa to the mouth of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

. Some Egyptologists dispute that an Egyptian pharaoh would authorize such an expedition, except for the reason of trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exc ...

in the ancient maritime routes.

The belief in Herodotus' account, handed down to him by oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and Culture, cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Traditio ...

, is primarily because he stated with disbelief that the Phoenicians "as they sailed on a westerly course round the southern end of Libya (Africa), they had the sun on their right – to northward of them" (''The Histories'' 4.42) – in Herodotus' time it was not generally known that Africa was surrounded by an ocean (with the southern part of Africa being thought connected to Asia). So fantastic an assertion is this of a typical example of some seafarers' story and Herodotus therefore may never have mentioned it at all, had it not been based on facts and made with the according insistence.

This early description of Necho's expedition as a whole is contentious, though; it is recommended that one keep an open mind on the subject, but Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

, Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

, and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

doubted the description. Egyptologist A. B. Lloyd suggests that the Greeks at this time understood that anyone going south far enough and then turning west would have the Sun on their right but found it unbelievable that Africa reached so far south. He suggests that "It is extremely unlikely that an Egyptian king would, or could, have acted as Necho is depicted as doing" and that the story might have been triggered by the failure of Sataspes' attempt to circumnavigate Africa under Xerxes the Great. Regardless, it was believed by Herodotus and Pliny.

Much earlier, the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

was a confederacy of seafaring raiders who sailed into the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, caused political unrest and attempted to enter or control Egyptian territory during the late 19th Dynasty

The Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XIX), also known as the Ramessid dynasty, is classified as the second Dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1292 BC to 1189 BC. The 19th Dynasty and the 20th Dynasty furt ...

, and especially during Year 8 of Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties furthermore toget ...

. The Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah

Merneptah or Merenptah (reigned July or August 1213 BC – May 2, 1203 BC) was the fourth pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. He ruled Egypt for almost ten years, from late July or early August 1213 BC until his death on May 2, ...

explicitly refers to them by the term "the foreign-countries (or 'peoples') of the sea" in his Great Karnak Inscription

The Great Karnak Inscription is an ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription belonging to the 19th Dynasty Pharaoh Merneptah. A long epigraph, it was discovered at Karnak in 1828–1829. According to Wilhelm Max Müller, it is "one of the famou ...

. Although some scholars believe that they "invaded" Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, this hypothesis is disputed.

Irrigation and agriculture

Irrigation as the artificial application of water to the soil was used to some extent in ancient Egypt, a hydraulic civilization (which entailshydraulic engineering

Hydraulic engineering as a sub-discipline of civil engineering is concerned with the flow and conveyance of fluids, principally water and sewage. One feature of these systems is the extensive use of gravity as the motive force to cause the m ...

). In crop production it is mainly used to replace missing rainfall in periods of drought, as opposed to reliance on direct rainfall (referred to as dryland farming or as rainfed farming). Before technology advanced, the people of Egypt relied on the natural flow of the Nile River to tend to the crops. Although the Nile provided sufficient watering for the survival of domesticated animals, crops, and the people of Egypt, there were times where the Nile would flood the area wreaking havoc across the land. There is evidence of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

Amenemhet III in the Twelfth Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some ...

(about 1800 BC) using the natural lake of the Fayûm as a reservoir to store surpluses of water for use during the dry seasons, as the lake swelled annually with the flooding of the Nile

The flooding of the Nile has been an important natural cycle in Egypt since ancient times. It is celebrated by Egyptians as an annual holiday for two weeks starting August 15, known as ''Wafaa El-Nil''. It is also celebrated in the Coptic Church ...

. Construction of drainage canals reduced the problems of major flooding from entering homes and areas of crops; but because it was a hydraulic civilization, much of the water management was controlled in a systematic way.

Glassworking

The earliest known

The earliest known glass

Glass is a non- crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenchin ...

beads from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

were made during the New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

around 1500 BC and were produced in a variety of colors. They were made by winding molten glass around a metal bar and were highly prized as a trading commodity, especially blue beads, which were believed to have magical powers. The Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

made small jars and bottles using the core-formed method. Glass threads were wound around a bag of sand tied to a rod. The glass was continually reheated to fuse the threads together. The glass-covered sand bag was kept in motion until the required shape and thickness was achieved. The rod was allowed to cool, then finally the bag was punctured and the sand poured out and reused . The Egyptians also created the first colored glass rods which they used to create colorful beads and decorations. They also worked with cast glass, which was produced by pouring molten glass into a mold, much like iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

and the more modern crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

.

Astronomy

The Egyptians were a practical people and this is reflected in their astronomy in contrast to Babylonia where the first astronomical texts were written in astrological terms. Even beforeUpper and Lower Egypt

In Egyptian history, the Upper and Lower Egypt period (also known as The Two Lands) was the final stage of prehistoric Egypt and directly preceded the unification of the realm. The conception of Egypt as the Two Lands was an example of the dual ...

were unified in 3000 BC, observations of the night sky had influenced the development of a religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

in which many of its principal deities

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater ...

were heavenly bodies. In Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, ...

, priests built circular mudbrick

A mudbrick or mud-brick is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of loam, mud, sand and water mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE, though since 4000 BCE, bricks have also been ...

walls with which to make a false horizon where they could mark the position of the sun as it rose at dawn, and then with a plumb-bob note the northern or southern turning points (solstices). This allowed them to discover that the sun disc, personified as Ra, took 365 days to travel from his birthplace at the winter solstice and back to it. Meanwhile, in Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient E ...

, a lunar calendar was being developed based on the behavior of the moon and the reappearance of Sirius

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. Its name is derived from the Greek word , or , meaning 'glowing' or 'scorching'. The star is designated α Canis Majoris, Latinized to Alpha Canis Majoris, and abbreviated Alpha CM ...

in its heliacal rising

The heliacal rising ( ) or star rise of a star occurs annually, or the similar phenomenon of a planet, when it first becomes visible above the eastern horizon at dawn just before sunrise (thus becoming "the morning star") after a complete orbit o ...

after its annual absence of about 70 days.

After unification, problems with trying to work with two calendars (both depending upon constant observation) led to a merged, simplified civil calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a phy ...

with twelve 30-day months, three seasons of four months each, plus an extra five days, giving a 365-year day but with no way of accounting for the extra quarter day each year. Day and night were split into 24 units, each personified by a deity. A sundial found on Seti I's cenotaph with instructions for its use shows us that the daylight hours were at one time split into 10 units, with 12 hours for the night and an hour for the morning and evening twilights. However, by Seti I's time day and night were normally divided into 12 hours each, the length of which would vary according to the time of year.

Key to much of this was the motion of the sun god Ra and his annual movement along the horizon at sunrise. Out of Egyptian myths such as those around Ra and the sky goddess Nut came the development of the Egyptian calendar, time keeping, and even concepts of royalty. An astronomical ceiling in the burial chamber of Ramesses VI

Ramesses VI Nebmaatre-Meryamun (sometimes written Ramses or Rameses, also known under his princely name of Amenherkhepshef C) was the fifth ruler of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. He reigned for about eight years in the mid-to-late 12th century ...

shows the sun being born from Nut in the morning, traveling along her body during the day and being swallowed at night.

During the Fifth Dynasty

The Fifth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty V) is often combined with Dynasties III, IV and VI under the group title the Old Kingdom. The Fifth Dynasty pharaohs reigned for approximately 150 years, from the early 25th century BC until ...

six kings built sun temples in honour of Ra. The temple complexes built by Niuserre at Abu Gurab

Abu Gorab (Arabic: أبو غراب , also known as Abu Gurab, Abu Ghurab) is a locality in Egypt situated south of Cairo, between Saqqarah and Al-Jīzah, about north of Abusir, on the edge of the desert plateau on the western bank of the Nile. ...

and Userkaf

Userkaf (known in Ancient Greek as , ) was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the founder of the Fifth Dynasty. He reigned for seven to eight years in the early 25th century BC, during the Old Kingdom period. He probably belonged to a branch of t ...

at Abusir

Abusir ( ar, ابو صير ; Egyptian ''pr wsjr'' cop, ⲃⲟⲩⲥⲓⲣⲓ ' "the House or Temple of Osiris"; grc, Βούσιρις) is the name given to an Egyptian archaeological locality – specifically, an extensive necropolis ...

have been excavated and have astronomical alignments, and the roofs of some of the buildings could have been used by observers to view the stars, calculate the hours at night and predict the sunrise for religious festivals.

Claims have been made that

Claims have been made that precession of the equinoxes

In astronomy, axial precession is a gravity-induced, slow, and continuous change in the orientation of an astronomical body's rotational axis. In the absence of precession, the astronomical body's orbit would show axial parallelism. In partic ...

was known in ancient Egypt prior to the time of Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the e ...

. This has been disputed however on the grounds that pre-Hipparchus texts do not mention precession and that "it is only by cunning interpretation of ancient myths and images, which are ostensibly about something else, that precession can be discerned in them, aided by some pretty esoteric numerological speculation involving the 72 years that mark one degree of shift in the zodiacal system and any number of permutations by multiplication, division, and addition."

Note however that the Egyptian observation of a slowly changing stellar alignment over a multi-year period does not necessarily mean that they understood or even cared what was going on. For instance, from the Middle Kingdom onwards they used a table with entries for each month to tell the time of night from the passing of constellations. These went in error after a few centuries because of their calendar and precession, but were copied (with scribal errors) long after they lost their practical usefulness or the possibility of understanding and use of them in the current years, rather than the years in which they were originally used.

Medicine

The

The Edwin Smith Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical text, named after Edwin Smith who bought it in 1862, and the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma. From a cited quotation in another text, it may have been known to ancient surgeons as t ...

is one of the first medical documents still extant, and perhaps the earliest document which attempts to describe and analyze the brain: given this, it might be seen as the very beginnings of neuroscience

Neuroscience is the science, scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions and disorders. It is a Multidisciplinary approach, multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, an ...

. However, medical historians believe that ancient Egyptian pharmacology was largely ineffective.Microsoft Word – Proceedings-2001.docAccording to a paper published by Michael D. Parkins, 72% of 260 medical prescriptions in the Hearst papyrus had no curative elements. According to Michael D. Parkins, sewage pharmacology first began in ancient Egypt and was continued through the Middle Ages, and while the use of animal dung can have curative properties, it is not without its risk. Practices such as applying cow dung to wounds, ear piercing, tattooing, and chronic ear infections were important factors in developing

tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

. Frank J. Snoek wrote that Egyptian medicine used fly specks, lizard blood, swine teeth, and other such remedies which he believes could have been harmful.

Mummification

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay furt ...

of the dead was not always practiced in Egypt. Once the practice

Practice or practise may refer to:

Education and learning

* Practice (learning method), a method of learning by repetition

* Phantom practice, phenomenon in which a person's abilities continue to improve, even without practicing

* Practice-based ...

began, an individual was placed at a final resting place through a set of rituals and protocol. The Egyptian funeral was a complex ceremony including various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in honor of the deceased. The poor, who could not afford expensive tombs, were buried in shallow graves in the sand, and because of the arid environment they were often naturally mummified.

The wheel

Evidence indicates that Egyptians made use ofpotter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, ...

s in the manufacturing of pottery from as early as the 4th Dynasty

The Fourth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty IV) is characterized as a "golden age" of the Old Kingdom of Egypt. Dynasty IV lasted from to 2494 BC. It was a time of peace and prosperity as well as one during which trade with other ...

(c. 2613 to 2494 BC). Chariots

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nbs ...

, however, are only believed to have been introduced by the invasion of the Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC).

T ...

in the Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when ancient Egypt fell into disarray for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a "Second Intermediate Period" was coined in 1942 b ...

(c.1650 BC to c.1550 BC); during the New Kingdom era (c.1550 BC to c.1077 BC), chariotry became central to Egypt's military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

.

Other developments

The Egyptians developed a variety offurniture

Furniture refers to movable objects intended to support various human activities such as seating (e.g., stools, chairs, and sofas), eating ( tables), storing items, eating and/or working with an item, and sleeping (e.g., beds and hammocks) ...

. There in the lands of ancient Egypt is the first evidence for stools, bed

A bed is an item of furniture that is used as a place to sleep, rest, and relax.

Most modern beds consist of a soft, cushioned mattress on a bed frame. The mattress rests either on a solid base, often wood slats, or a sprung base. Many beds ...

s, and tables (such as from the tombs similar to Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

's). Recovered Ancient Egyptian furniture includes a third millennium BC bed discovered in the Tarkhan Tomb, a c.2550 BC. gilded set from the tomb of Queen Hetepheres I

Hetepheres I was a queen of Egypt during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2600 BC) who was a wife of one king, the mother of the next king, the grandmother of two more kings, and the figure who tied together two dynasties.

Biography

Het ...

, and a c. 1550 BC. stool from Thebes.

Some have suggested that the Egyptians had some form of understanding

Some have suggested that the Egyptians had some form of understanding electric

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by ...

phenomena

A phenomenon ( : phenomena) is an observable event. The term came into its modern philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be directly observed. Kant was heavily influenced by Gottfried ...

from observing lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

and interacting with electric fish

An electric fish is any fish that can generate electric fields. Most electric fish are also electroreceptive, meaning that they can sense electric fields. The only exception is the stargazer family. Electric fish, although a small minority, inc ...

(such as '' Malapterurus electricus'') or other animals (such as electric eel

The electric eels are a genus, ''Electrophorus'', of neotropical freshwater fish from South America in the family Gymnotidae. They are known for their ability to stun their prey by generating electricity, delivering shocks at up to 860 volt ...

s). The comment about lightning appears to come from a misunderstanding of a text referring to "high poles covered with copper plates" to argue this but Dr. Bolko Stern has written in detail explaining why the copper covered tops of poles (which were lower than the associated pylons) do not relate to electricity or lightning, pointing out that no evidence of anything used to manipulate electricity had been found in Egypt and that this was a magical and not a technical installation.

Those exploring fringe theories

A fringe theory is an idea or a viewpoint which differs from the accepted scholarship of the time within its field. Fringe theories include the models and proposals of fringe science, as well as similar ideas in other areas of scholarship, such ...

of ancient technology

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

have suggested that there were electric lights used in Ancient Egypt. Engineers have constructed a working model based on their interpretation of a relief found in the Hathor

Hathor ( egy, ḥwt-ḥr, lit=House of Horus, grc, Ἁθώρ , cop, ϩⲁⲑⲱⲣ, Meroitic: ) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky ...

temple at the Dendera Temple complex.Krassa, P., and R. Habeck, "''Das Licht der Pharaonen.''". (Tr. ''The Light of the Pharaohs'') Authors (such as Peter Krassa and Reinhard Habeck) have produced a basic theory of the device's operation. The standard explanation, however, for the Dendera light, which comprises three stone reliefs (one single and a double representation) is that the depicted image represents a lotus leaf and flower from which a sacred snake is spawned in accordance with Egyptian mythological beliefs. This sacred snake sometimes is identified as the Milky Way (the snake) in the night sky (the leaf, lotus, or "bulb") that became identified with Hathor because of her similar association in creation.

Later technology in Egypt

Greco-Roman Egypt

Under Hellenistic rule, Egypt was one of the most prosperous regions of theHellenistic civilization

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

. The ancient Egyptian city of Rhakotis

Rhacotis (Egyptian: ''r-ꜥ-qd(y)t'', Greek ''Ῥακῶτις''; also romanized as Rhakotis) was the name for a city on the northern coast of Egypt at the site of Alexandria. Classical sources from the Greco-Roman era in both Ancient Greek and ...

was renovated as Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, which became the largest city around the Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

. Under Roman rule, Egypt was one of the most prosperous regions of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, with Alexandria being second only to ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom ...

in size.

Recent scholarship suggests that the water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

originates from Ptolemaic Egypt, where it appeared by the 3rd century BC. This is seen as an evolution of the paddle-driven water-lifting wheels that had been known in Egypt a century earlier. According to John Peter Oleson

John Peter Oleson (born 1946) is a Canadian classical archaeologist and historian of ancient technology. His main interests are the Roman Near East, maritime archaeology (particularly Roman harbours), and ancient technology, especially hydrauli ...

, both the compartmented wheel and the hydraulic noria

A noria ( ar, ناعورة, ''nā‘ūra'', plural ''nawāʿīr'', from syr, ܢܥܘܪܐ, ''nā‘orā'', lit. "growler") is a hydropowered '' scoop wheel'' used to lift water into a small aqueduct, either for the purpose of irrigation or to s ...

may have been invented in Egypt by the 4th century BC, with the Sakia

A sāqiyah or saqiya ( ar, ساقية), also spelled sakia or saqia) is a mechanical water lifting device. It is also called a Persian wheel, tablia, rehat, and in Latin tympanum. It is similar in function to a scoop wheel, which uses buckets, ...

being invented there a century later. This is supported by archeological finds at Faiyum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, where the oldest archeological evidence of a water-wheel has been found, in the form of a Sakia dating back to the 3rd century BC. A papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to ...

dating to the 2nd century BC also found in Faiyum mentions a water wheel used for irrigation, a 2nd-century BC fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plast ...

found at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

depicts a compartmented Sakia, and the writings of Callixenus of Rhodes mention the use of a Sakia in Ptolemaic Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy IV

egy, Iwaennetjerwymenkhwy Setepptah Userkare Sekhemankhamun Clayton (2006) p. 208.

, predecessor = Ptolemy III

, successor = Ptolemy V

, horus = ''ḥnw-ḳni sḫꜤi.n-sw-it.f'Khunuqeni sekhaensuitef'' The strong youth whose f ...

in the late 3rd century BC.

Ancient Greek technology

Ancient Greek technology developed during the 5th century BC, continuing up to and including the Roman period, and beyond. Inventions that are credited to the ancient Greeks include the gear, screw, rotary mills, bronze casting techniques, water ...

was often inspired by the need to improve weapons and tactics in war. Ancient Roman technology

Roman technology is the collection of antiques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome (753 BC – 476 AD).

The R ...

is a set of artifacts and customs which supported Roman civilization and made the expansion of Roman commerce and Roman military possible over nearly a thousand years.

Arabic-Islamic Egypt

Under Arab rule, Egypt once again became one of the most prosperous regions around the Mediterranean. The Egyptian city ofCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

was founded by the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a ...

and served as its capital city. At the time, Cairo was second only to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, capital of the rival Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

. After the fall of Baghdad, however, Cairo overtook it as the largest city in the Mediterranean region until the early modern period.

Inventions in medieval Islam

The following is a list of inventions made in the medieval Islamic world, especially during the Islamic Golden Age, George Saliba (1994), ''A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam'', pp. 245, 250, 256–57 ...

covers the inventions developed in the medieval Islamic world, a region that extended from Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

in the west to the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

in the east. The timeline of Islamic science and engineering covers the general development of science and technology in the Islamic world.

See also

* List of Egypt-related topics *List of Egyptian inventions and discoveries

Egyptian inventions and discoveries are objects, processes or techniques which owe their existence or first known written account either partially or entirely to an Egyptian person.

Ancient Egypt

Government and Economy

* Community banking ...

* Ancient Egyptian units of measurement

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

* Egyptian chronology

The majority of Egyptologists agree on the outline and many details of the chronology of Ancient Egypt. This scholarly consensus is the so-called Conventional Egyptian chronology, which places the beginning of the Old Kingdom in the 27th centur ...

* History of science in early cultures

* Astrology and astronomy

* History of technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques and is one of the categories of world history. Technology can refer to methods ranging from as simple as stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and inf ...

Notes

References