Anarchism and education on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

to '' The False Principle of our Education'' by

For English enlightenment anarchist

For English enlightenment anarchist

by

The Memory Hole

Stirner thus saw education "is to be life and there, as outside of it, the self-revelation of the individual is to be the task." For him "pedagogy should not proceed any further towards civilizing, but toward the development of free men, sovereign characters".

What do anarchists want from us?

''

by

Russian

Russian

Revolt Library

/ref> So for Kropotkin "We fully recognise the necessity of specialisation of knowledge, but we maintain that specialisation must follow general education, and that general education must be given in science and handicraft alike. To the division of society into brainworkers and manual workers we oppose the combination of both kinds of activities; and instead of 'technical education,' which means the maintenance of the present division between brain work and manual work, we advocate the éducation intégrale, or complete education, which means the disappearance of that pernicious distinction."

The Russian

The Russian

In 1901,

In 1901,

/ref> Read "elaborated a socio-cultural dimension of creative education, offering the notion of greater international understanding and cohesiveness rooted in principles of developing the fully balanced personality through art education. Read argued in Education through Art that "every child, is said to be a potential neurotic capable of being saved from this prospect, if early, largely inborn, creative abilities were not repressed by conventional Education. Everyone is an artist of some kind whose special abilities, even if almost insignificant, must be encouraged as contributing to an infinite richness of collective life. Read's newly expressed view of an essential 'continuity' of child and adult creativity in everyone represented a synthesis' the two opposed models of twentieth-century art education that had predominated until this point...Read did not offer a curriculum but a theoretical defence of the genuine and true. His claims for genuineness and truth were based on the overwhelming evidence of characteristics revealed in his study of child art...From 1946 until his death in 1968 he was president of the Society for Education in Art (SEA), the renamed ATG, in which capacity he had a platform for addressing

Anarchist texts on education at the Anarchist Library

{{Anarchism Education policy Alternative education Anarchist theory

Anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

has had a special interest on the issue of education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

from the works of William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

and Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

Introductionto '' The False Principle of our Education'' by

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

by James J. Martin onwards.

A wide diversity of issues related to education have gained the attention of anarchist theorists and activists. They have included the role of education in social control and socialization

In sociology, socialization or socialisation (see spelling differences) is the process of internalizing the norms and ideologies of society. Socialization encompasses both learning and teaching and is thus "the means by which social and cul ...

, the rights and liberties of youth and children within educational contexts, the inequalities encouraged by current educational systems, the influence of state and religious ideologies

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied prim ...

in the education of people, the division between social and manual work and its relationship with education, sex education

Sex education, also known as sexual education, sexuality education or sex ed, is the instruction of issues relating to human sexuality, including emotional relations and responsibilities, human sexual anatomy, sexual activity, sexual reproduc ...

and art education

Visual arts education is the area of learning that is based upon the kind of art that one can see, visual arts

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, filmmaking, de ...

.

Various alternatives to contemporary mainstream educational systems and their problems have been proposed by anarchists which have gone from alternative education systems and environments, self-education

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning and self-teaching) is education without the guidance of masters (such as teachers and professors) or institutions (such as schools). Generally, autodidacts are individu ...

, advocacy of youth

Youth is the time of life when one is young. The word, youth, can also mean the time between childhood and adulthood ( maturity), but it can also refer to one's peak, in terms of health or the period of life known as being a young adult. Yo ...

and children rights, and freethought activism.

Early anarchist views on education

William Godwin

For English enlightenment anarchist

For English enlightenment anarchist William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

education was "the main means by which change would be achieved." Godwin saw that the main goal of education should be the promotion of happiness. For Godwin, education had to have "A respect for the child's autonomy which precluded any form of coercion", "A pedagogy that respected this and sought to build on the child's own motivation and initiatives" and "A concern about the child's capacity to resist an ideology transmitted through the school."

In his ''Political Justice

''Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness'' is a 1793 book by the philosopher William Godwin, in which the author outlines his political philosophy. It is the first modern work to expound anarchism.

Backg ...

'', he criticizes state sponsored schooling "on account of its obvious alliance with national government."Political Justiceby

William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

For him the State "will not fail to employ it to strengthen its hands, and perpetuate its institutions." He thought "It is not true that our youth ought to be instructed to venerate the constitution, however excellent; they should be instructed to venerate truth; and the constitution only so far as it corresponded with their independent deductions of truth." A long work on the subject of education to consider is ''The Enquirer. Reflections On Education, Manners, And Literature. In A Series Of Essays.''

Max Stirner

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

was a German philosopher linked mainly with the anarchist school of thought known as individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean by individualism th ...

who worked as a schoolteacher in a gym

A gymnasium, also known as a gym, is an indoor location for athletics. The word is derived from the ancient Greek term " gymnasium". They are commonly found in athletic and fitness centres, and as activity and learning spaces in educational i ...

nasium for young girls. He examines the subject of education directly in his long essay '' The False Principle of our Education''. In it "we discern his persistent pursuit of the goal of individual self-awareness and his insistence on the centering of everything around the individual personality". As such Stirner "in education, all of the given material has value only in so far as children learn to do something with it, to use it". In that essay he deals with the debates between realist and humanistic educational commentators and sees that both "are concerned with the learner as an object, someone to be acted upon rather than one encouraged to move toward subjective self-realization and liberation" and sees that "a knowledge which only burdens me as a belonging and a possession, instead of having gone along with me completely so that the free-moving ego, not encumbered by any dragging possessions, passes through the world with a fresh spirit, such a knowledge then, which has not become personal, furnishes a poor preparation for life".

He concludes this essay by saying that "the necessary decline of non-voluntary learning and rise of the self-assured will which perfects itself in the glorious sunlight of the free person may be expressed somewhat as follows: knowledge must die and rise again as will and create itself anew each day as a free person."'' The False Principle of our Education'' by Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

aThe Memory Hole

Stirner thus saw education "is to be life and there, as outside of it, the self-revelation of the individual is to be the task." For him "pedagogy should not proceed any further towards civilizing, but toward the development of free men, sovereign characters".

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

is widely regarded as the first American anarchist.Palmer, Brian (2010-12-29What do anarchists want from us?

''

Slate.com

''Slate'' is an online magazine that covers current affairs, politics, and culture in the United States. It was created in 1996 by former '' New Republic'' editor Michael Kinsley, initially under the ownership of Microsoft as part of MSN. In 2 ...

'' "Where utopian projectors starting with Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

entertained the idea of creating an ideal species through eugenics and education and a set of universally valid institutions inculcating shared identities, Warren wanted to dissolve such identities in a solution of individual self-sovereignty. His educational experiments, for example, possibly under the influence of the...Swiss educational theorist Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (, ; 12 January 1746 – 17 February 1827) was a Swiss pedagogue and educational reformer who exemplified Romanticism in his approach.

He founded several educational institutions both in German- and French-speaking ...

(via Robert Owen), emphasized—as we would expect—the nurturing of the independence and the conscience of individual children, not the inculcation of pre-conceived values."

Late 19th century

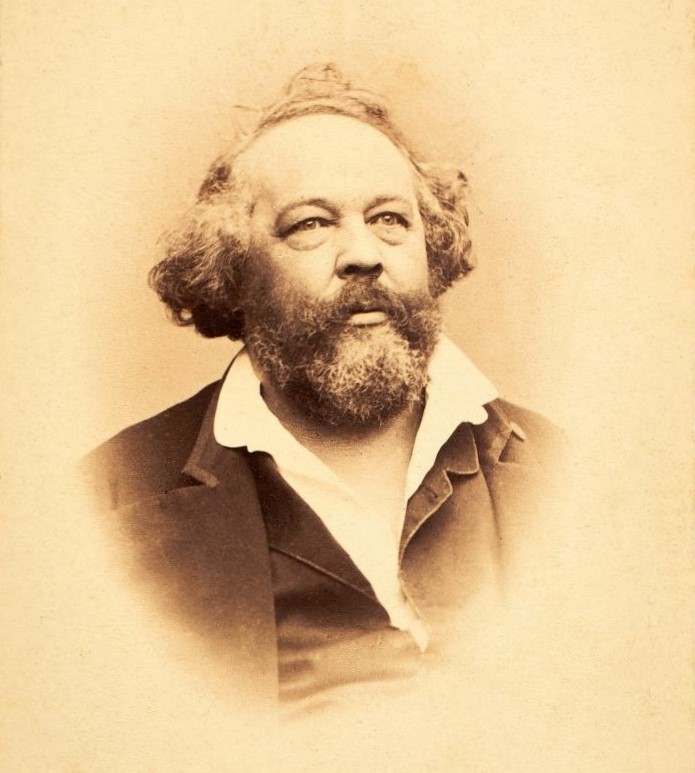

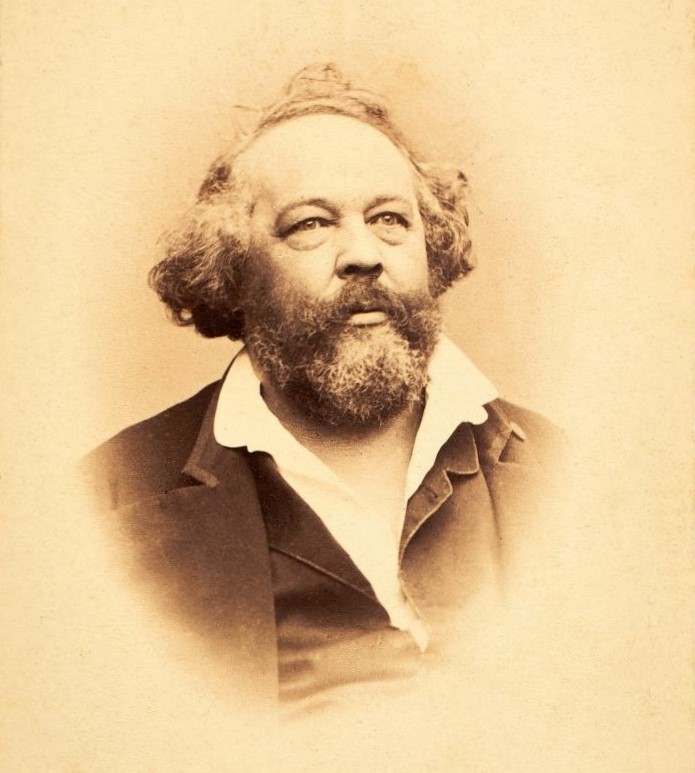

Mikhail Bakunin

On "Equal Opportunity in Education""Equal Opportunity in Education"by

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

denounced what he saw as the social inequalities caused by the current educational systems. He put this issue in this way "will it be feasible for the working masses to know complete emancipation as long as the education available to those masses continues to be inferior to that bestowed upon the bourgeois, or, in more general terms, as long as there exists any class, be it numerous or otherwise, which, by virtue of birth, is entitled to a superior education and a more complete instruction? Does not the question answer itself?..."

He also denounced that "Consequently while some study others must labour so that they can produce what we need to live — not just producing for their own needs, but also for those men who devote themselves exclusively to intellectual pursuits. As a solution to this Bakunin proposed that "Our answer to that is a simple one: everyone must work and everyone must receive education...for work's sake as much as for the sake of science, there must no longer be this division into workers and scholars and henceforth there must be only men. "

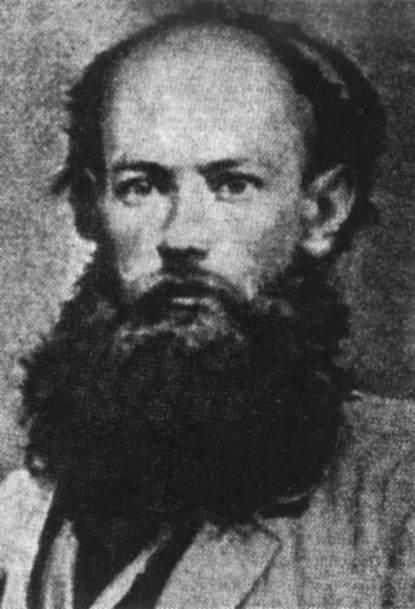

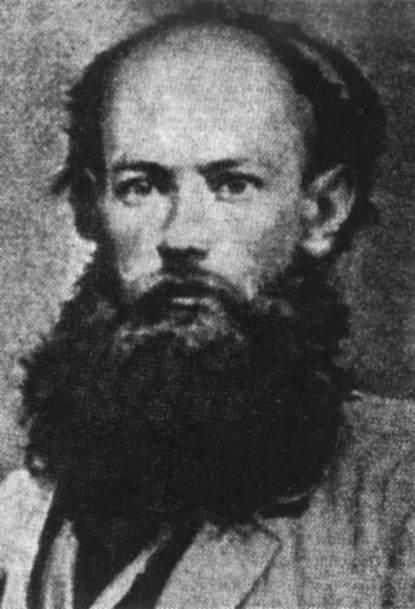

Peter Kropotkin

Russian

Russian anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

theorist Peter Kropotkin suggested in "Brain Work and Manual Work" that "The masses of the workmen do not receive more scientific education than their grandfathers did; but they have been deprived of the education of even the small workshop, while their boys and girls are driven into a mine, or a factory, from the age of thirteen, and there they soon forget the little they may have learned at school. As to the scientists, they despise manual labour."'' Fields, Factories and Workshops: or Industry Combined with Agriculture and Brain Work with Manual Work'' by Peter Kropotkin aRevolt Library

/ref> So for Kropotkin "We fully recognise the necessity of specialisation of knowledge, but we maintain that specialisation must follow general education, and that general education must be given in science and handicraft alike. To the division of society into brainworkers and manual workers we oppose the combination of both kinds of activities; and instead of 'technical education,' which means the maintenance of the present division between brain work and manual work, we advocate the éducation intégrale, or complete education, which means the disappearance of that pernicious distinction."

Early 20th century

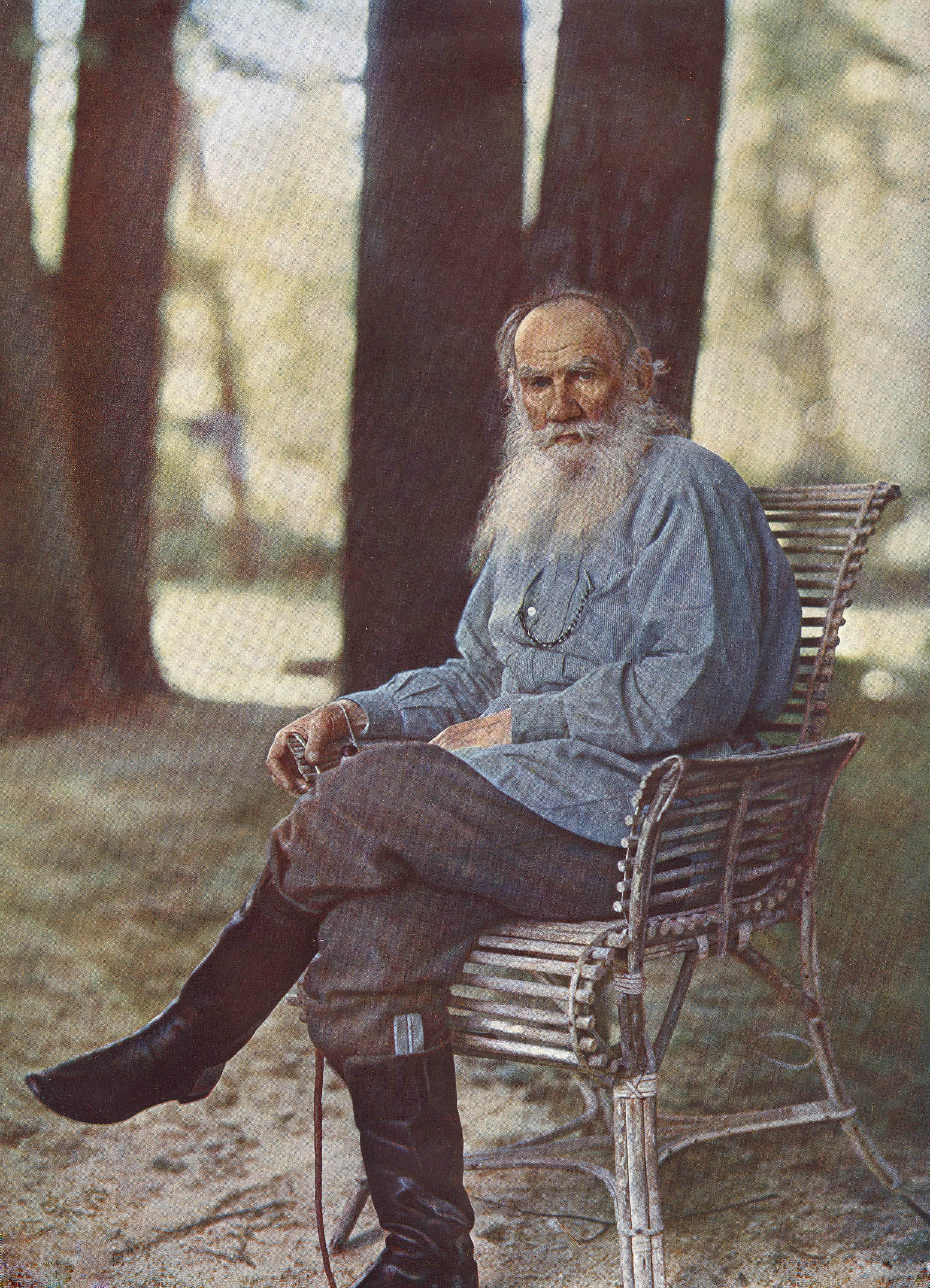

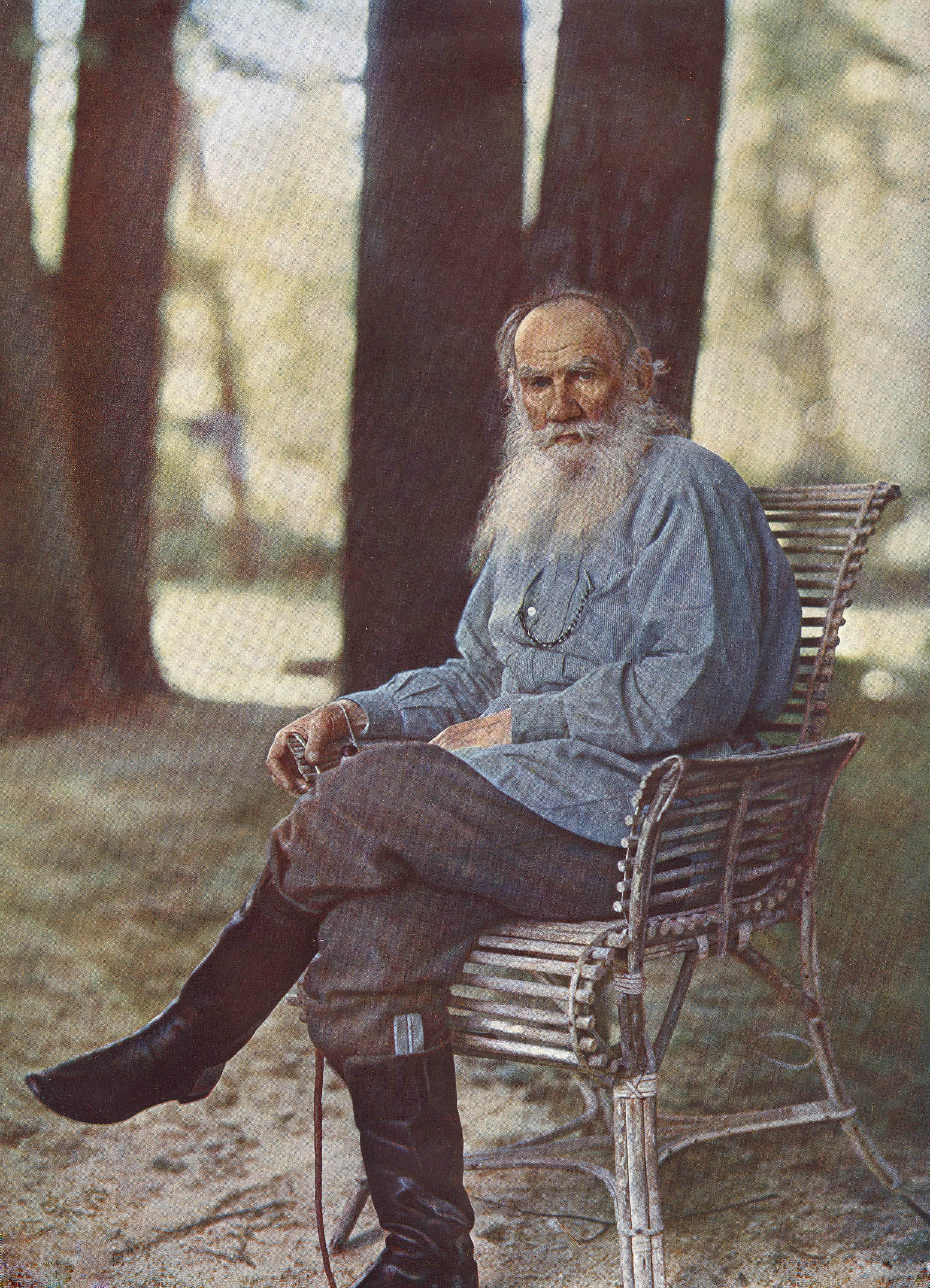

Leo Tolstoy

The Russian

The Russian christian anarchist

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately an ...

and famous novelist Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

established a school for peasant children on his estate. Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded thirteen schools for his serfs' children, based on the principles Tolstoy described in his 1862 essay "The School at Yasnaya Polyana". Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived due to harassment by the Tsarist secret police, but as a direct forerunner to A. S. Neill's Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed to be the first example of a coherent theory of democratic education.

Tolstoy differentiated between education and culture. He wrote that "Education is the tendency of one man to make another just like himself... Education is culture under restraint, culture is free. ducation iswhen the teaching is forced upon the pupil, and when then instruction is exclusive, that is when only those subjects are taught which the educator regards as necessary". For him "without compulsion, education was transformed into culture".

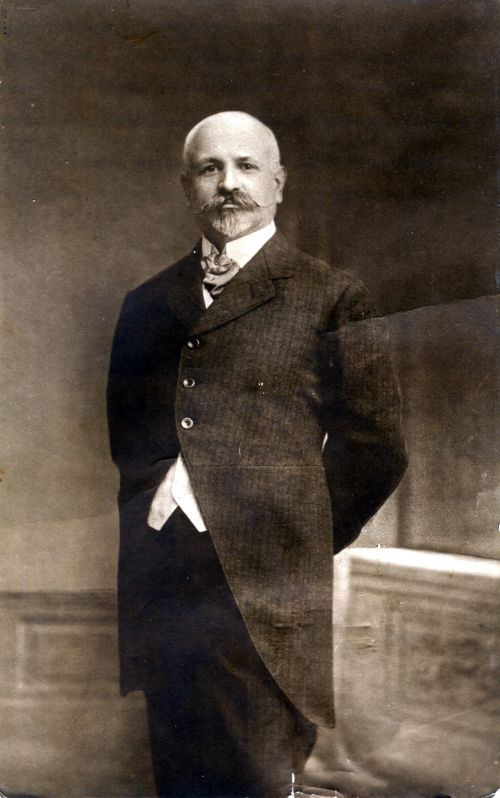

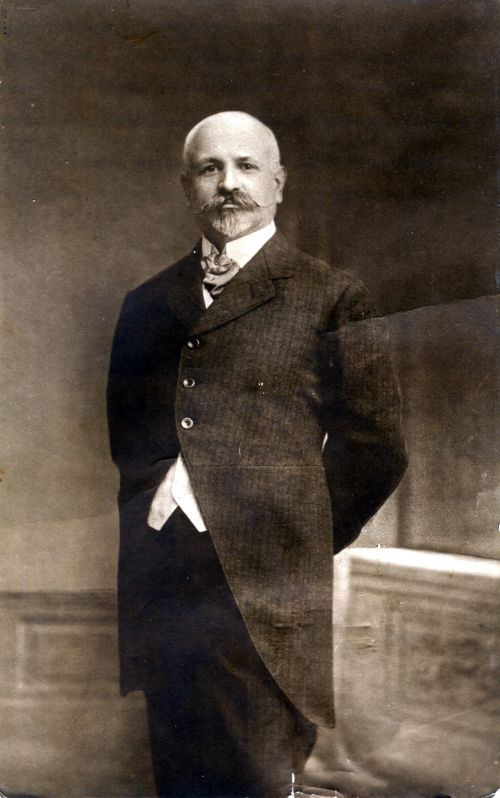

Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia and Modern schools

In 1901,

In 1901, Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

anarchist and free-thinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

Francisco Ferrer

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia (; January 14, 1859 – October 13, 1909), widely known as Francisco Ferrer (), was a Spanish radical freethinker, anarchist, and educationist behind a network of secular, private, libertarian schools in and aroun ...

established "modern" or progressive schools in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

in defiance of an educational system controlled by the Catholic Church. The schools' stated goal was to " educate the working class in a rational, secular and non-coercive setting". Fiercely anti-clerical, Ferrer believed in "freedom in education", education free from the authority of church and state. Murray Bookchin wrote: "This period 890swas the heyday of libertarian schools and pedagogical projects in all areas of the country where Anarchists exercised some degree of influence. Perhaps the best-known effort in this field was Francisco Ferrer's Modern School (Escuela Moderna), a project which exercised a considerable influence on Catalan education and on experimental techniques of teaching generally." La Escuela Moderna, and Ferrer's ideas generally, formed the inspiration for a series of '' Modern Schools'' in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

and London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. The first of these was started in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

in 1911. It also inspired the Italian newspaper '' Università popolare'', founded in 1901.

Ferrer wrote an extensive work on education and on his educational experiments called ''The Origin and Ideals of the Modern School''.

The Modern School movement in the United States

The Modern Schools, also called Ferrer Schools, wereUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes comp ...

s, established in the early twentieth century, that were modeled after the Escuela Moderna

The Ferrer school was an early 20th century libertarian school inspired by the anarchist pedagogy of Francisco Ferrer. He was a proponent of rationalist, secular education that emphasized reason, dignity, self-reliance, and scientific observatio ...

of Francisco Ferrer, the Catalan educator and anarchist. They were an important part of the anarchist, free schooling, socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

, and labor movements in the U.S., intended to educate the working-classes from a secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

, class-conscious perspective. The Modern Schools imparted day-time academic classes for children, and night-time continuing-education lectures for adults.

The first, and most notable, of the Modern Schools was founded in New York City, in 1911, two years after Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia's execution for sedition in monarchist Spain on 18 October 1909. Commonly called the Ferrer Center, it was founded by notable anarchists — including Leonard Abbott, Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

, Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre (November 17, 1866 – June 20, 1912) was an American anarchist known for being a prolific writer and speaker who opposed capitalism, marriage and the state as well as the domination of religion over sexuality and women's li ...

, and Emma Goldman — first meeting on St. Mark's Place, in Manhattan's Lower East Side, but twice moved elsewhere, first within lower Manhattan, then to Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

. The Ferrer Center opened with only nine students, one being the son of Margaret Sanger, the contraceptives-rights activist. Starting in 1912, the school's principal was the philosopher Will Durant

William James Durant (; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He became best known for his work '' The Story of Civilization'', which contains 11 volumes and details the history of eastern a ...

, who also taught there. Besides Berkman and Goldman, the Ferrer Center faculty included the Ashcan School

The Ashcan School, also called the Ash Can School, was an artistic movement in the United States during the late 19th-early 20th century that produced works portraying scenes of daily life in New York, often in the city's poorer neighborhoods.

...

painters Robert Henri

Robert Henri (; June 24, 1865 – July 12, 1929) was an American painter and teacher.

As a young man, he studied in Paris, where he identified strongly with the Impressionists, and determined to lead an even more dramatic revolt against A ...

and George Bellows, and its guest lecturers included writers and political activists such as Margaret Sanger, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, and Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

. Student Magda Schoenwetter, recalled that the school used Montessori

The Montessori method of education involves children's natural interests and activities rather than formal teaching methods. A Montessori classroom places an emphasis on hands-on learning and developing real-world skills. It emphasizes indepen ...

methods and equipment, and emphasised academic freedom rather than fixed subjects, such as spelling and arithmetic. ''The Modern School'' magazine originally began as a newsletter for parents, when the school was in New York City, printed with the manual printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

used in teaching printing as a profession. After moving to the Stelton Colony, New Jersey, the magazine's content expanded to poetry, prose, art, and libertarian education articles; the cover emblem and interior graphics were designed by Rockwell Kent

Rockwell Kent (June 21, 1882 – March 13, 1971) was an American painter, printmaker, illustrator, writer, sailor, adventurer and voyager.

Biography

Rockwell Kent was born in Tarrytown, New York. Kent was of English descent. He lived much of ...

. Artists and writers, among them Hart Crane and Wallace Stevens

Wallace Stevens (October 2, 1879 – August 2, 1955) was an American modernist poet. He was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, educated at Harvard and then New York Law School, and spent most of his life working as an executive for an insurance compa ...

, praised ''The Modern School'' as "the most beautifully printed magazine in existence."

After the 4 July 1914 Lexington Avenue bombing

The Lexington Avenue explosion was the July 4, 1914, explosion of a terrorist bomb in an apartment at 1626 Lexington Avenue in New York City. Members of the Lettish section of the Anarchist Black Cross (ABC) were constructing a bomb in a sev ...

, the police investigated and several times raided the Ferrer Center and other labor and anarchist organisations in New York City.Avrich, Paul, ''The Modern School Movement''. Princeton: Princeton University Press (1980); Avrich, Paul, ''Anarchist Portraits

''Anarchist Portraits'' is a 1988 history book by Paul Avrich about the lives and personalities of multiple prominent and inconspicuous anarchists.

*Mikhail Bakunin

* Peter Kropotkin

* Chummy Fleming

*Sergey Nechayev

*Sacco and Vanzetti

* Nestor ...

'', Princeton: Princeton University Press, (1988) Acknowledging the urban danger to their school, the organizers bought 68 acres (275,000 m2) in Piscataway Township, New Jersey

Piscataway () is a township in Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States. It is a suburb of the New York metropolitan area, in the Raritan Valley. At the 2010 United States Census, the population was 56,044, an increase of 5,562 (+11.0%) f ...

, and moved there in 1914, becoming the center of the Stelton Colony. Moreover, beyond New York City, the Ferrer Colony and Modern School

The Ferrer Center and Stelton Colony were an anarchist social center and colony, respectively, organized to honor the memory of anarchist pedagogue Francisco Ferrer and to build a school based on his model in the United States.

In the widespre ...

was founded (–1915) as a Modern School-based community, that endured some forty years. In 1933, James and Nellie Dick, who earlier had been principals of the Stelton Modern School, founded the Modern School in Lakewood, New Jersey

Lakewood Township is the most populous township in Ocean County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. A rapidly growing community as of the 2020 U.S. census, the township had a total population of 135,158 representing an increase of 41,415 (+45.5% ...

, which survived the original Modern School, the Ferrer Center, becoming the final surviving such school, lasting until 1958.

Late 20th century to present

Experiments in Germany led to A. S. Neill founding what became Summerhill School in 1921. Summerhill is often cited as an example of anarchism in practice. British anarchistsStuart Christie

Stuart Christie (10 July 1946 – 15 August 2020) was a Scottish anarchist writer and publisher. When aged 18, Christie was arrested while carrying explosives to assassinate the Spanish caudillo, General Francisco Franco. He was later alleged ...

and Albert Meltzer

Albert Isidore Meltzer (7 January 1920 – 7 May 1996) was an English anarcho-communist activist and writer.

Early life

Meltzer was born in Hackney, London, of Jewish ancestry, and educated at The Latymer School, Edmonton. He was attracted to ...

manifested that "A.S. Neill is the modern pioneer of libertarian education and of "hearts not heads in the school". Although he has denied being an anarchist, it would be hard to know how else to describe his philosophy, though he is correct in recognising the difference between revolution in philosophy and pedagogy, and the revolutionary change of society. They are associated but not the same thing." However, although Summerhill and other free schools are radically libertarian, they differ in principle from those of Ferrer by not advocating an overtly political class struggle-approach.

Herbert Read

The English anarchist philosopher, art critic and poet, Herbert Read developed a strong interest in the subject of education and particularly inart education

Visual arts education is the area of learning that is based upon the kind of art that one can see, visual arts

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, filmmaking, de ...

. Read's anarchism was influenced by William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

, Peter Kropotkin and Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

. Read "became deeply interested in children's drawings and paintings after having been invited to collect works for an exhibition of British art that would tour allied and neutral countries during the Second World War. As it was considered too risky to transport across the Atlantic works of established importance to the national heritage, it was proposed that children's drawings and paintings should be sent instead. Read, in making his collection, was unexpectedly moved by the expressive power and emotional content of some of the younger artist's works. The experience prompted his special attention to their cultural value, and his engagement of the theory of children's creativity with seriousness matching his devotion to the avant-garde. This work both changed fundamentally his own life's work throughout his remaining twenty-five years and provided art education with a rationale of unprecedented lucidity and persuasiveness. Key books and pamphlets resulted: ''Education through Art'' (Read, 1943); ''The Education of Free Men'' (Read, 1944); ''Culture and Education in a World Order'' (Read, 1948); ''The Grass Read'', (1955); and ''Redemption of the Robot'' (1970)".David Thistlewood. "HERBERT READ (1893–1968)" in ''PROSPECTS: the quarterly review of comparative education''. Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, vol. 24, no.1/2, 1994, p. 375–90/ref> Read "elaborated a socio-cultural dimension of creative education, offering the notion of greater international understanding and cohesiveness rooted in principles of developing the fully balanced personality through art education. Read argued in Education through Art that "every child, is said to be a potential neurotic capable of being saved from this prospect, if early, largely inborn, creative abilities were not repressed by conventional Education. Everyone is an artist of some kind whose special abilities, even if almost insignificant, must be encouraged as contributing to an infinite richness of collective life. Read's newly expressed view of an essential 'continuity' of child and adult creativity in everyone represented a synthesis' the two opposed models of twentieth-century art education that had predominated until this point...Read did not offer a curriculum but a theoretical defence of the genuine and true. His claims for genuineness and truth were based on the overwhelming evidence of characteristics revealed in his study of child art...From 1946 until his death in 1968 he was president of the Society for Education in Art (SEA), the renamed ATG, in which capacity he had a platform for addressing

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

...On the basis of such representation Read, with others, succeeded in establishing the International Society for Education through Art (INSEA)

as an executive arm of UNESCO in 1954.""

Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (1911–1972) was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Goodman was prolific across numerous literary genres and non-fiction topics, including the arts, civil rights, decen ...

was an important anarchist critic of contemporary educational systems as can be seen in his books ''Growing Up Absurd

''Growing Up Absurd'' is a 1960 book by Paul Goodman on the relationship between American juvenile delinquency and societal opportunities to fulfill natural needs. Contrary to the then-popular view that juvenile delinquents should be led to re ...

'' and '' Compulsory Mis-education''. Goodman believed that in contemporary societies "It is in the schools and from the mass media, rather than at home or from their friends, that the mass of our citizens in all classes learn that life is inevitably routine, depersonalized, venally graded; that it is best to toe the mark and shut up; that there is no place for spontaneity, open sexuality and free spirit. Trained in the schools they go on to the same quality of jobs, culture and politics. This is education, miseducation socializing to the national norms and regimenting to the nation's "needs".

Goodman thought that a person's most valuable educational experiences Goodman wrote of his contemporaneous 1960s American schooling: "The basic intention behind the compulsory attendance laws is not only to insure the socialization process but also to control the labour supply quantitatively within an industrialized economy characterized by unemployment and inflation. The public schools and universities have become large holding tanks of potential workers."

Ivan Illich

The termdeschooling

Deschooling is a term invented by Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich. Today, the word is mainly used by homeschoolers, especially unschoolers, to refer to the transition process that children and parents go through when they leave the school system ...

was popularized by Ivan Illich

Ivan Dominic Illich ( , ; 4 September 1926 – 2 December 2002) was an Austrian Roman Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and social critic. His 1971 book ''Deschooling Society'' criticises modern society's institutional approach to educ ...

, who argued that the school as an institution is dysfunctional for self-determined learning and serves the creation of a consumer society instead. Illich thought that "the dismantling of the public education system would coincide with a pervasive abolition of all the suppressive institutions of society". Illich "charges public schooling with institutionalizing acceptable moral and behavioral standards and with constitutionally violating the rights of young adults." IIlich subscribes to Goodman's belief that most

of the useful education that people acquire is a by-product of work or leisure and not of the school. Illich refers to this process as "informal education". Only through this unrestricted and unregulated form of learning can the individual

gain a sense of self-awareness and develop his creative capacity to its fullest extent." Illich thought that the main goals of an alternative education systems should be "to provide access to available resources to all who want to learn: to empower

all who want to share what they know; to find those who want to learn it from them; to furnish all who want to present an issue to the public with the opportunity to make their challenges known. The system of learning webs is aimed at individual freedom and expression in education by using society as the classroom. There would be reference services to index items available for study in laboratories, theatres, airports, libraries, etc.; skill exchanges which would permit people to list their skills so that potential students could contact them; peer-matching, which would communicate an individual's interest so that he or she could find educational associates; reference services to educators at large, which would be a central directory of professionals, para professionals and freelancers."

Colin Ward

English anarchistColin Ward

Colin Ward (14 August 1924 – 11 February 2010)

in his main theoretical publication ''Anarchy in Action

''Anarchy in Action'' is a book exploring anarchist thought and practice, written by Colin Ward and first published in 1973.

The book is a seminal introduction to anarchism but differs considerably to others by concentrating on the possibility ...

'' (1973) in a chapter called "Schools No Longer" "discusses the genealogy of education and schooling, in particular examining the writings of Everett Reimer

Everett W. Reimer (1910–1998

) was an e ...

and Ivan Illich, and the beliefs of anarchist educator Paul Goodman. Many of Colin's writings in the 1970s, in particular ''Streetwork: The Exploding School'' (1973, with Anthony Fyson), focused on learning practices and spaces outside of the school building. In introducing ''Streetwork'', Ward writes, ") was an e ...

his

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

is a book about ideas: ideas of the environment as the educational resource, ideas of the enquiring school, the school without walls..." In the same year, Ward contributed to ''Education Without Schools'' (edited by Peter Buckman) discussing 'the role of the state'. He argued that "one significant role of the state in the national education systems of the world is to perpetuate social and economic injustice"".

In ''The Child in the City'' (1978), and later ''The Child in the Country'' (1988), Ward "examined the everyday spaces of young people's lives and how they can negotiate and re-articulate the various environments they inhabit. In his earlier text, the more famous of the two, Colin Ward explores the creativity and uniqueness of children and how they cultivate 'the art of making the city work'. He argued that through play, appropriation and imagination, children can counter adult-based intentions and interpretations of the built environment. His later text, The Child in the Country, inspired a number of social scientists, notably geographer Chris Philo (1992), to call for more attention to be paid to young people as a 'hidden' and marginalised group in society."

See also

*Anarchistic free school

Self-managed social centers, also known as autonomous social centers, are self-organized community centers in which anti-authoritarians put on voluntary activities. These autonomous spaces, often in multi-purpose venues affiliated with anarc ...

* Alternative education

*Democratic education

Democratic education is a type of formal education that is organized democratically, so that students can manage their own learning and participate in the governance of their school. Democratic education is often specifically emancipatory, wit ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Anarchist texts on education at the Anarchist Library

{{Anarchism Education policy Alternative education Anarchist theory