Amy Robsart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Amy, Lady Dudley (

From December 1559 until her death, Amy Dudley lived at Cumnor Place, also sometimes known as Cumnor Hall, in the village of

From December 1559 until her death, Amy Dudley lived at Cumnor Place, also sometimes known as Cumnor Hall, in the village of

On Sunday, 8 September 1560, the day of a fair at Abingdon, Amy Robsart was found dead at the foot of a set of stairs at Cumnor Place. Robert Dudley, at

On Sunday, 8 September 1560, the day of a fair at Abingdon, Amy Robsart was found dead at the foot of a set of stairs at Cumnor Place. Robert Dudley, at

Amy Dudley's death, happening amid renewed rumours about the Queen and her favourite, caused "grievous and dangerous suspicion, and muttering" in the country. Robert Dudley was shocked,Adams 2008 dreading "the malicious talk that I know the wicked world will use". William Cecil, the Queen's

Amy Dudley's death, happening amid renewed rumours about the Queen and her favourite, caused "grievous and dangerous suspicion, and muttering" in the country. Robert Dudley was shocked,Adams 2008 dreading "the malicious talk that I know the wicked world will use". William Cecil, the Queen's

From the early 1560s there was a tradition involving Sir Richard Verney, a gentleman-retainer of Robert Dudley from Warwickshire, in whose house Lady Amy Dudley had stayed in 1559. A 1563 chronicle, which is heavily biased against the House of Dudley and was probably written by the Protestant activist

From the early 1560s there was a tradition involving Sir Richard Verney, a gentleman-retainer of Robert Dudley from Warwickshire, in whose house Lady Amy Dudley had stayed in 1559. A 1563 chronicle, which is heavily biased against the House of Dudley and was probably written by the Protestant activist

The coroner's report came to light in

The coroner's report came to light in

"Dudley, Robert, earl of Leicester (1532/3–1588)"

''

"Dudley, Amy, Lady Dudley (1532–1560)"

''

''Calendar of the Manuscripts of ... The Marquess of Salisbury ... Preserved at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire''

Vol. I HMSO * Historical Manuscripts Commission (ed.) (1911)

''Report on the Pepys Manuscripts Preserved at Magdalen College, Cambridge''

HMSO * Ives, Eric (2009): ''Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery'' Wiley-Blackwell * Jenkins, Elizabeth (2002): ''Elizabeth and Leicester'' The Phoenix Press * Loades, David (1996): ''John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland 1504–1553'' Clarendon Press * Loades, David (2004): ''Intrigue and Treason: The Tudor Court, 1547–1558'' Pearson/Longman * Skidmore, Chris (2010): ''Death and the Virgin: Elizabeth, Dudley and the Mysterious Fate of Amy Robsart'' Weidenfeld & Nicolson * Weir, Alison (1999): ''The Life of Queen Elizabeth I'' Ballantine Books * Wilson, Derek (1981): ''Sweet Robin: A Biography of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester 1533–1588'' Hamish Hamilton * Wilson, Derek (2005): ''The Uncrowned Kings of England: The Black History of the Dudleys and the Tudor Throne'' Carroll & Graf

''Amye Robsart and the Earl of Leycester''

(1870) * Peggy Inman

Cumnor History Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Robsart, Amy 1532 births 1560 deaths 16th-century English women

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Robsart; 7 June 1532 – 8 September 1560) was the first wife of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was o ...

, favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated s ...

of Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

. She is primarily known for her death by falling down a flight of stairs, the circumstances of which have often been regarded as suspicious. Robsart was the only child of a substantial Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

gentleman

A gentleman (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man) is any man of good and courteous conduct. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire and above a yeoman; by definition, the r ...

. In the vernacular of the day, her name was spelled as Amye Duddley.

At nearly 18 years of age, she married Robert Dudley, a son of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady J ...

. In 1553, Robert Dudley was condemned to death and imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, where Amy Dudley was allowed to visit him. After his release the couple lived in straitened financial circumstances until, with the accession of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

in late 1558, Dudley became Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(Ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse ( la, Magister Equitu ...

, an important court office. The Queen soon fell in love with him and there was talk that Amy Dudley, who did not follow her husband to court, was suffering from an illness, and that Elizabeth would perhaps marry her favourite should his wife die. The rumours grew more sinister when Elizabeth remained single against the common expectation that she would accept one of her many foreign suitors.

Amy Dudley lived with friends in different parts of the country, having her own household and hardly ever seeing her husband. In the morning of 8 September 1560, at Cumnor Place near Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, she insisted on sending away her servants and later was found dead at the foot of a flight of stairs with a broken neck and two wounds on her head. The coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner's jur ...

's jury's finding was that she had died of a fall downstairs; the verdict was "misfortune", accidental death.

Amy Dudley's death caused a scandal. Despite the inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a c ...

's outcome, Robert Dudley was widely suspected to have orchestrated his wife's demise, a view not shared by most modern historians. He remained Elizabeth's closest favourite, but with respect to her reputation she could not risk a marriage with him. A tradition that Sir Richard Verney, a follower of Robert Dudley, organized Amy Dudley's violent death evolved early, and '' Leicester's Commonwealth'', a notorious and influential libel of 1584 against Robert Dudley, by then Earl of Leicester, perpetuated this version of events. Interest in Amy Dudley's fate was rekindled in the 19th century by Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

's novel, ''Kenilworth

Kenilworth ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Warwick District in Warwickshire, England, south-west of Coventry, north of Warwick and north-west of London. It lies on Finham Brook, a tributary of the River Sowe, which joins the ...

''. The most widely accepted modern explanations of her death have been breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or ...

and suicide, although a few historians have probed murder scenarios. The medical evidence of the coroner's report, which was found in 2008, is compatible with accident as well as suicide and other violence.

Life

Amy Robsart was born inNorfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, the heiress of a substantial gentleman-farmer and grazier, Sir John Robsart of Syderstone, and his wife, Elizabeth Scott. Amy Robsart grew up at her mother's house, Stanfield Hall (near Wymondham

Wymondham ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the South Norfolk district of Norfolk, England, south-west of Norwich off the A11 road to London. The River Tiffey runs through. The parish, one of Norfolk's largest, includes rural areas to ...

), and, like her future husband, in a firmly Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

household. She received a good education and wrote in a fine hand. Three days before her 18th birthday she married Robert Dudley, a younger son of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jan ...

. Amy and Robert, who were of the same age, probably first met about ten months before their wedding. The wedding contract of May 1550 specified that Amy would inherit her father's estate only after both her parents' death, and after the marriage the young couple depended heavily on both their fathers' gifts, especially Robert's. It was most probably a love-match, a "carnal marriage", as the wedding guest William Cecil later commented disapprovingly. The marriage was celebrated on 4 June 1550 at the royal palace of Sheen, with Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

in attendance.

The Earl of Warwick and future Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke o ...

was the most powerful man in England, leading the government of the young King Edward VI. The match, though by no means a prize, was acceptable to him as it strengthened his influence in Norfolk. The young couple dwelt mostly at court or with Amy's parents-in-law at Ely House; in the first half of 1553 they lived at Somerset House

Somerset House is a large Neoclassical complex situated on the south side of the Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadrangle was built on the site of a Tudor palace ("O ...

, Robert Dudley being keeper of this great Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

palace. In May 1553 Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

became Amy Dudley's sister-in-law, and after her rule of a fortnight as England's queen, Robert Dudley was sentenced to death and imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

. He remained there from July 1553 until October 1554; from September 1553 Amy was allowed to visit "and there to tarry with" him at the Tower's Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

's pleasure.

After his release Robert Dudley was short of money and he and Amy were helped out financially by their families. Their lifestyle had to remain modest, though, and Lord Robert (as he was known) was heaping up considerable debts. Sir John Robsart died in 1554; his wife followed him to the grave in the spring of 1557, which meant that the Dudleys could inherit the Robsart estate with the Queen's permission. Lady Amy's ancestral manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals ...

of Syderstone had been uninhabitable for many decades, and the couple were now living in Throcking, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

, at the house of William Hyde, when not in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. In August 1557, Robert Dudley went to fight for Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

(who was then Mary I's husband) at the Battle of St. Quentin in France.

From this time a business letter from Amy Dudley survives, settling some of her husband's debts in his absence, "although I forgot to move my lord thereof before his departing, he being sore troubled with weighty affairs, and I not being altogether in quiet for his sudden departing".

In the summer of 1558, Robert and Amy Dudley were looking for a suitable residence of their own in order to settle in Norfolk; nothing came of this, however, before the death of Queen Mary I in November 1558. Upon the accession of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

Robert Dudley became Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(Ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse ( la, Magister Equitu ...

and his place was now at court at almost constant attendance on the Queen. By April 1559, Queen Elizabeth seemed to be in love with Lord Robert, and several diplomats reported that some at court already speculated that the Queen would marry him, "in case his wife should die", as Lady Amy Dudley was very ill in one of her breasts. Very soon court observers noted that Elizabeth never let Robert Dudley from her side. He visited his wife at Throcking for a couple of days at Easter 1559, and Amy Dudley came to London in May 1559 for about a month.Adams 1995 p. 378 At this time, on 6 June, the new Spanish ambassador de Quadra wrote that her health had improved, but that she was careful with her food. She also made a trip to Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

; by September she was residing in the house of Sir Richard Verney at Compton Verney

Compton Verney is a parish and historic manor in the county of Warwickshire, England. The population taken at the 2011 census was 119. The surviving manor house is the Georgian mansion Compton Verney House.

Descent of the manor

The first ...

in Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avo ...

.

By late 1559, several foreign princes were vying for the Queen's hand; indignant at Elizabeth's little serious interest in their candidate, the Spanish ambassador de Quadra and his Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

colleague were informing each other and their superiors that Lord Robert was sending his wife poison and that Elizabeth was only fooling them, "keeping Lord Robert's enemies and the country engaged with words until this wicked deed of killing his wife is consummated". Parts of the nobility also held Dudley responsible for Elizabeth's failure to marry, and plots to assassinate him abounded. In March 1560 de Quadra informed Philip II: "Lord Robert told somebody … that if he live another year he will be in a very different position from now. … They say that he thinks of divorcing his wife." Lady Amy never saw her husband again after her London visit in 1559. A projected trip of his to visit her and other family never materialized. Queen Elizabeth did not really allow her favourite a wife; according to a contemporary court chronicle, he "was commanded to say that he did nothing with her, when he came to her, as seldom he did".

Cumnor

Cumnor is a village and civil parish 3½ miles (5.6 km) west of the centre of Oxford, England. The village is about 2 miles (3.2 km) south-west of Botley and its centre is west of the A420 road to Swindon. The parish includes Cumn ...

in Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Ber ...

(on the outskirts of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and now in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primaril ...

). The house, an altered 14th century monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

complex, was rented by a friend of the Dudleys and possible relative of Amy, Sir Anthony Forster.Adams 2011 He lived there with his wife and Mrs. Odingsells and Mrs. Owen, relations of the house's owner. Lady Amy's chamber was a large, sumptuous upper story apartment, the best of the house, with a separate entrance and staircase leading up to it. At the house's rear there were a terrace garden

In gardening, a terrace is an element where a raised flat paved or gravelled section overlooks a prospect. A raised terrace keeps a house dry and provides a transition between the hardscape and the softscape.

History

;Persia

Since a level si ...

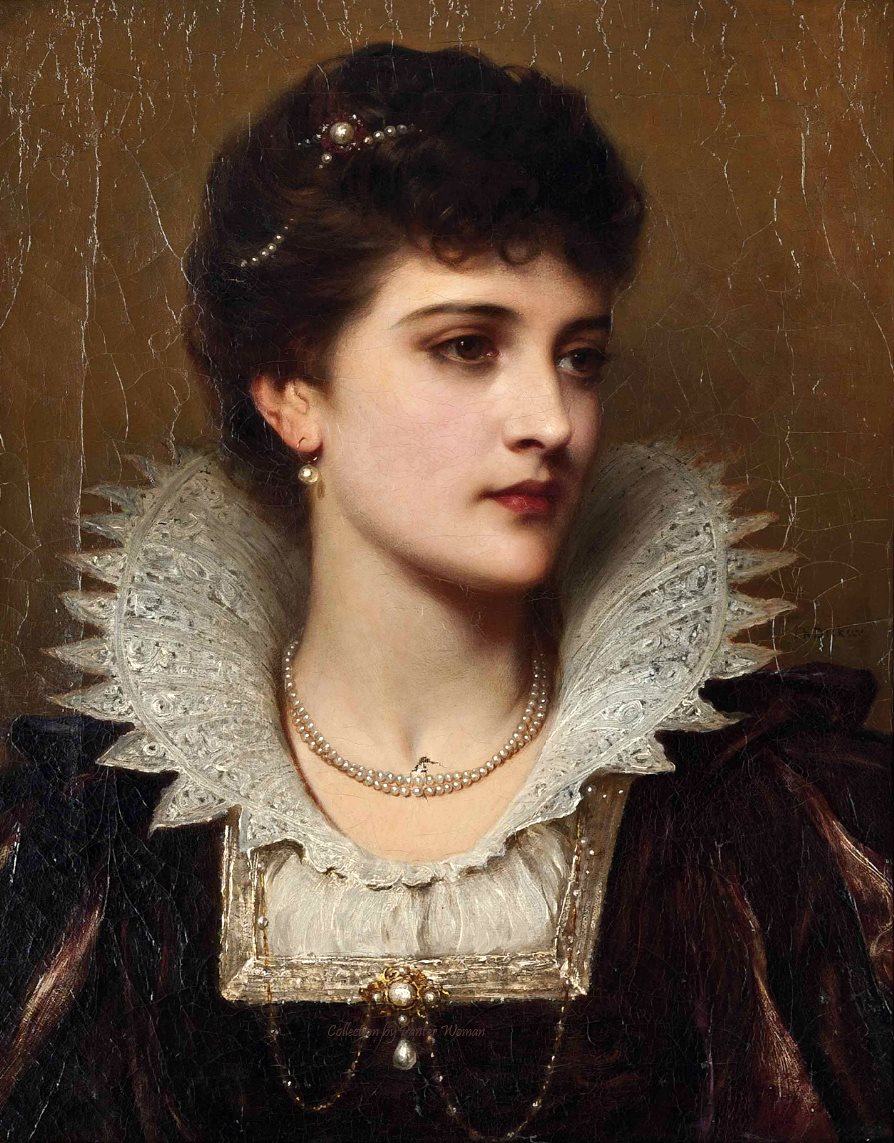

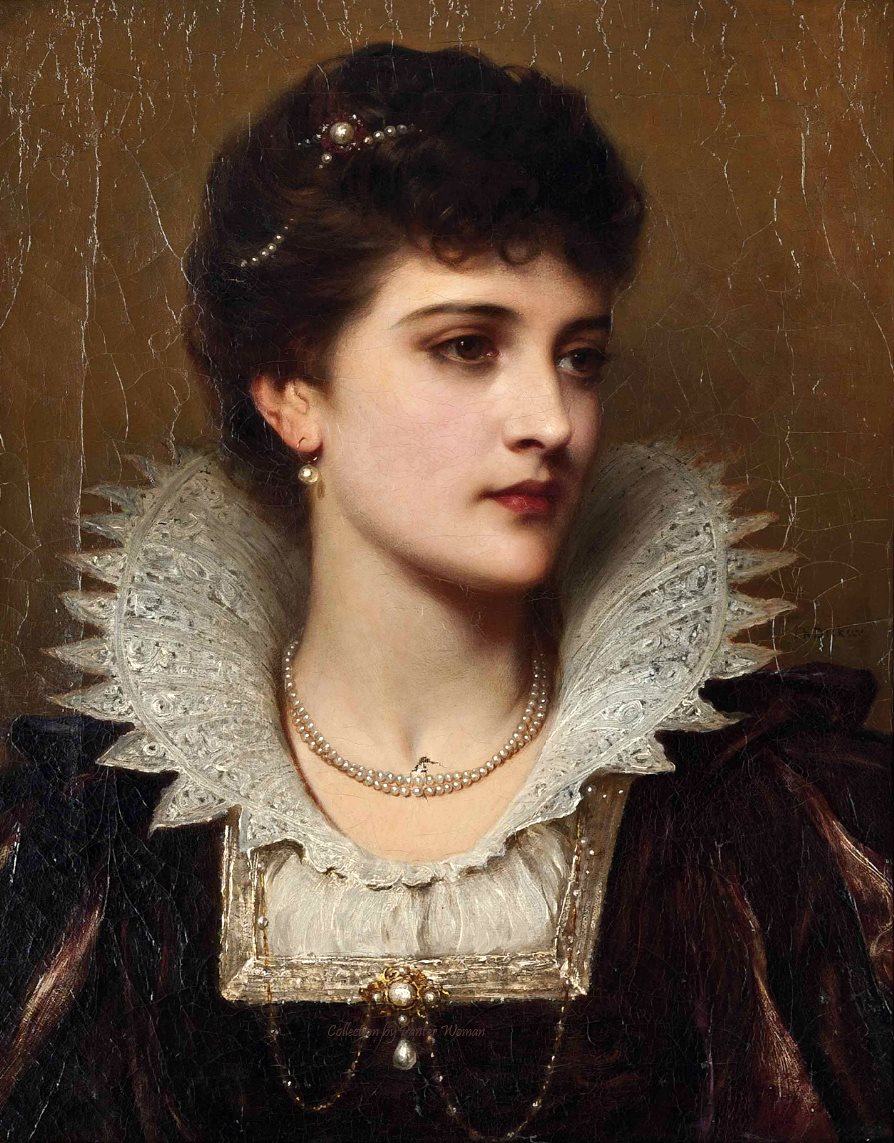

, a pond, and a deer park. Amy Dudley received the proceeds of the Robsart estate directly into her hands and largely paid for her own household, which comprised about 10 servants. She regularly ordered dresses and finery as accounts and a letter from her of as late as 24 August 1560 show. She also received presents from her husband. No picture of her is known to have survived, though according to the Imperial ambassador Caspar Breuner, writing in 1559, she was "a very beautiful wife".

However, in 2009, Eric Ives

Eric William Ives (12 July 1931 – 25 September 2012) was a British historian who was an expert on the Tudor period, and a university administrator. He was Emeritus Professor of English History at the University of Birmingham.

Early life

...

suggested that a portrait miniature now in the Yale Center for British Art,Ives 2009 pp. 295, 15–16 the Yale Miniature, was, in fact, Amy Robsart. Chris Skidmore

Christopher James Skidmore, (born 17 May 1981) is a British politician, and author of popular history. He served as Minister of State for Universities, Science, Research and Innovation from December 2018 to July 2019, and from September 2019 ...

concurs with this in his 2010 book ''Death and the Virgin: Elizabeth, Dudley and the Mysterious Fate of Amy Robsart'', adding that Robert Dudley used the oak as a personal symbol in his youth, the sitter wearing oak leaves and gillyflowers at her breast. Recently a point has been made of the fact that the sprig of yellow flowers at the lady's breast corresponds with the colours of the Robsart coat of arms, green and yellow, or ''Vert'' and ''Or''. The name gilliflower or gillyflower derives from the French giroflée from Greek ''karyophyllon'' meaning ''nut-leaf'', the association deriving from the flower's scent, making it another possible wordplay for oak for Robert or even Robsart, ''Robur'' being Latin for oak. A portrait miniature of the same woman was sold at Sotheby's in 1983 by the Duke of Beaufort, a direct descendant of Lettice Knollys

Lettice Knollys ( , sometimes latinized as Laetitia, alias Lettice Devereux or Lettice Dudley), Countess of Essex and Countess of Leicester (8 November 1543Adams 2008a – 25 December 1634), was an English noblewoman and mother to the courtier ...

, who was the second wife of Amy's widower Robert Dudley.

Death and inquest

On Sunday, 8 September 1560, the day of a fair at Abingdon, Amy Robsart was found dead at the foot of a set of stairs at Cumnor Place. Robert Dudley, at

On Sunday, 8 September 1560, the day of a fair at Abingdon, Amy Robsart was found dead at the foot of a set of stairs at Cumnor Place. Robert Dudley, at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

with the Queen, was told of her death by a messenger on 9 September and immediately wrote to his steward

Steward may refer to:

Positions or roles

* Steward (office), a representative of a monarch

* Steward (Methodism), a leader in a congregation and/or district

* Steward, a person responsible for supplies of food to a college, club, or other ins ...

Thomas Blount, who had himself just departed for Cumnor. He desperately urged him to find out what had happened and to call for an inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a c ...

; this had already been opened when Blount arrived. He informed his master that Lady Amy Dudley had risen early and

would not that day suffer one of her own sort to tarry at home, and was so earnest to have them gone to the fair, that with any of her own sort that made reason of tarrying at home she was very angry, and came to Mrs. Odingsells … who refused that day to go to the fair, and was very angry with her also. Because rs. Odingsellssaid it was no day for gentlewomen to go … Whereunto my lady answered and said that she might choose and go at her pleasure, but all hers should go; and was very angry. They asked who should keep her company if all they went; she said Mrs. Owen should keep her company at dinner; the same tale doth Picto, who doth dearly love her, confirm. Certainly, my Lord, as little while as I have been here, I have heard divers tales of her that maketh me judge her to be a strange woman of mind.Mrs. Picto was Lady Amy Dudley's maid and Thomas Blount asked whether she thought what had happened was "chance or villany":

she said by her faith she doth judge very chance, and neither done by man nor by herself. For herself, she said, she was a good virtuous gentlewoman, and daily would pray upon her knees; and divers times she saith that she hath heard her pray to God to deliver her from desperation. Then, said I, she might have an evil toy uicidein her mind. No, good Mr. Blount, said Picto, do not judge so of my words; if you should so gather, I am sorry I said so much.Blount continued, wondering:

My Lord, it is most strange that this chance should fall upon you. It passeth the judgment of any man to say how it is; but truly the tales I do hear of her maketh me to think she had a strange mind in her: as I will tell you at my coming.Skidmore 2010 p. 382The

coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner's jur ...

and the 15 jurors were local gentlemen and yeomen

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

of substance. A few days later Blount wrote that some of the jury were no friends of Anthony Forster (a good sign that they would not "conceal any fault, if any be") and that they were proceeding very thoroughly: they be very secret, and yet do I hear a whispering that they can find no presumptions of evil. And if I may say to your Lordship my conscience: I think some of them be sorry for it, God forgive me. … Mine own opinion is much quieted … the circumstances and as many things as I can learn doth persuade me that only misfortune hath done it, and nothing else.The jury's foreman assured Robert Dudley in a letter of his own that for all they could find out, it appeared to be an accident.Wilson 1981 p. 122 Dudley, desperately seeking to avert damage from what he called "my case", was relieved to hear the impending outcome, but thought "another substantial company of honest men" should undertake a further investigation "for more knowledge of truth". This panel should include any of Lady Amy's available friends and her half-brothers John Appleyard and Arthur Robsart, both of whom he had ordered to Cumnor immediately after Amy's death. Nothing came of this proposal.Gristwood 2007 p. 107 The coroner's verdict, pronounced at the local

Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ...

on 1 August 1561, was that Lady Amy Dudley, "being alone in a certain chamber … accidentally fell precipitously down" the adjoining stairs "to the very bottom of the same".Skidmore 2010 p. 378 She had sustained two head injuries

A head injury is any injury that results in trauma to the skull or brain. The terms ''traumatic brain injury'' and ''head injury'' are often used interchangeably in the medical literature. Because head injuries cover such a broad scope of inju ...

—one "of the depth of a quarter of a thumb", the other "of the depth of two thumbs". She had also, "by reason of the accidental injury or of that fall and of Lady Amy's own body weight falling down the aforesaid stairs", broken her neck, "on account of which … the same Lady Amy then and there died instantly; … and thus the jurors say on their oath that the Lady Amy … by misfortune came to her death and not otherwise, as they are able to agree at present".

Amy Dudley was buried at St. Mary's, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, in August 1560 with full pomp, including attendance by the Garter King of Arms

The Garter Principal King of Arms (also Garter King of Arms or simply Garter) is the senior King of Arms, and the senior Officer of Arms of the College of Arms, the heraldic authority with jurisdiction over England, Wales and Northern Ireland. ...

and other heralds, which cost Dudley some £2,000 (roughly £1 million in 2021). He wore mourning for about six months but, as was within custom, did not attend the funeral, where Lady Amy Dudley's half-brothers, neighbours, as well as city and county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposes Chambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

prominence played the leading parts. The court went into mourning for over a month; Robert Dudley retired to his house at Kew.Adams, Archer, and Bernard 2003 p. 66

Aftermath

Amy Dudley's death, happening amid renewed rumours about the Queen and her favourite, caused "grievous and dangerous suspicion, and muttering" in the country. Robert Dudley was shocked,Adams 2008 dreading "the malicious talk that I know the wicked world will use". William Cecil, the Queen's

Amy Dudley's death, happening amid renewed rumours about the Queen and her favourite, caused "grievous and dangerous suspicion, and muttering" in the country. Robert Dudley was shocked,Adams 2008 dreading "the malicious talk that I know the wicked world will use". William Cecil, the Queen's Principal Secretary The Principal Secretary is a senior government official in various Commonwealth countries.

* Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister of Pakistan

* Principal Secretary to the President of Pakistan

* Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister of Ind ...

, felt himself threatened by the prospect of Dudley's becoming king consort and spread rumours against the eventuality.

Already knowing of her death before it was officially made public, he told the Spanish ambassador that Lord Robert and the Queen wished to marry and were about to do away with Lady Amy Dudley by poison, "giving out that she was ill but she was not ill at all". Likewise strongly opposed to a Dudley marriage, Nicholas Throckmorton

Sir Nicholas Throckmorton (or Throgmorton) (c. 1515/151612 February 1571) was an English diplomat and politician, who was an ambassador to France and later Scotland, and played a key role in the relationship between Elizabeth I of Englan ...

, the English ambassador in France, went out of his way to draw attention to the scandalous gossip he heard at the French court. Although Cecil and Throckmorton made use of the scandal for their political and personal aims, they did not believe themselves that Robert Dudley had orchestrated his wife's death.

In October Robert Dudley returned to court, many believed, "in great hope to marry the Queen".Doran 1996 p. 45 Elizabeth's affection and favour towards him was undiminished, and, importuned by unsolicited advice against a marriage with Lord Robert, she declared the inquest had shown "the matter … to be contrary to which was reported" and to "neither touch his honesty nor her honour."

However, her international reputation and even her position at home were imperilled by the scandal, which seems to have convinced her that she could not risk a marriage with Dudley. Dudley himself had no illusions about his destroyed reputation, even when he was first notified of the jury's decision: "God's will be done; and I wish he had made me the poorest that creepeth on the ground, so this mischance had not happened to me." In September 1561, a month after the coroner's verdict was officially passed, the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The ...

, one of Dudley's principal enemies, studied the testimonies in the hope of finding incriminating evidence against his rival.

John Appleyard

John Appleyard had profited in terms of offices and annuities from his brother-in-law's rise ever since 1559; he was nevertheless disappointed with what he had got from Robert Dudley, now Earl of Leicester. In 1567 he was approached, apparently on behalf of theDuke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

and the Earl of Sussex

Earl of Sussex is a title that has been created several times in the Peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. The early Earls of Arundel (up to 1243) were often also called Earls of Sussex.

The fifth creation came in the Peer ...

, to accuse Leicester of the murder of his wife for a reward of £1,000 in cash.Wilson 1981 p. 182 He refused to cooperate in the plot, although he had, he said, in the last few years come to believe that his half-sister was murdered. He had always been convinced of Dudley's innocence but thought it would be an easy matter to find out the real culprits. He said he had repeatedly asked for the Earl's help to this effect, claiming the jury had not yet come up with their verdict; Dudley had always answered that the matter should rest, since a jury had found that there was no murder, by due procedure of law. Now, as Leicester became aware of a plot against him, he summoned Appleyard and sent him away after a furious confrontation.

Some weeks later the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

investigated the allegations about Norfolk, Sussex, and Leicester, and Appleyard found himself in the Fleet prison for about a month. Interrogated by Cecil and a panel of noblemen (among them the Earl of Arundel, but not Robert Dudley), he was commanded to answer in writing what had moved him to implicate "my Lord of Norfolk, the Earl of Sussex and others to stir up matter against my Lord of Leicester for the death of his wife", and what had moved him to say that "the death of the Earl of Leicester's wife" was "procured by any person". Appleyard, instead of giving answers, retracted all his statements; he had also requested to see the coroner's report and, after studying it in his cell, wrote that it fully satisfied him and had dispelled his concerns.

Early traditions and theories

From the early 1560s there was a tradition involving Sir Richard Verney, a gentleman-retainer of Robert Dudley from Warwickshire, in whose house Lady Amy Dudley had stayed in 1559. A 1563 chronicle, which is heavily biased against the House of Dudley and was probably written by the Protestant activist

From the early 1560s there was a tradition involving Sir Richard Verney, a gentleman-retainer of Robert Dudley from Warwickshire, in whose house Lady Amy Dudley had stayed in 1559. A 1563 chronicle, which is heavily biased against the House of Dudley and was probably written by the Protestant activist John Hales John Hales may refer to:

*John Hales (theologian) (1584–1656), English theologian

* John Hales (bishop of Exeter) from 1455 to 1456

* John Hales (bishop of Coventry and Lichfield) (died 1490) from 1459 to 1490

* John Hales (died 1540), MP for Cant ...

, describes the rumours:e Lord Robert's wife brake her neck at Forster's house in Oxfordshire … her gentlewomen being gone forth to a fair. Howbeit it was thought she was slain, for Sir ----- Varney was there that day and whylest the deed was doing was going over the fair and tarried there for his man, who at length came, and he said, thou knave, why tarriest thou? He answered, should I come before I had done? Hast thou done? quoth Varney. Yeah, quoth the man, I have made it sure. … Many times before it was bruited by the Lord Robert his men that she was dead. … This Verney and divers his servants used before her death, to wish her death, which made the people to suspect the worse.The first printed version of Amy Robsart's alleged murder appeared in the satirical libel '' Leicester's Commonwealth'', a notorious propaganda work against the Earl of Leicester written by

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

exiles in 1584. Here Sir Richard Verney goes directly to Cumnor Place, forces the servants to go to the market, and breaks Lady Amy's neck before placing her at the foot of the stairs; the jury's verdict is murder, and she is buried first secretly at the Cumnor parish church before being dug up and reburied at Oxford. Verney dies, communicating "that all the devils in hell" tore him in pieces; his servant (who was with him at the murder) having been killed in prison by Dudley's means before he could tell the story.

Enhanced by the considerable influence of ''Leicester's Commonwealth'', the rumours about Amy Robsart's death developed into a tradition of embellished folklore. As early as 1608, a domestic tragedy named ''A Yorkshire Tragedy

''A Yorkshire Tragedy'' is an early Jacobean era stage play, a domestic tragedy printed in 1608. The play was originally assigned to William Shakespeare, though the modern critical consensus rejects this attribution, favouring Thomas Middleto ...

'' alluded to her fall from a pair of stairs as an easy way to get rid of one's wife: "A politician did it." In the 19th century her story became very popular due to the best-selling novel, ''Kenilworth

Kenilworth ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Warwick District in Warwickshire, England, south-west of Coventry, north of Warwick and north-west of London. It lies on Finham Brook, a tributary of the River Sowe, which joins the ...

'', by Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

. The novel's arch-villain is again called Varney. The notion that Amy Robsart was murdered gained new strength with the discovery of the Spanish diplomatic correspondence (and with it of poison rumours) by the Victorian historian James Anthony Froude

James Anthony Froude ( ; 23 April 1818 – 20 October 1894) was an English historian, novelist, biographer, and editor of '' Fraser's Magazine''. From his upbringing amidst the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement, Froude intended to become a clerg ...

. Generally convinced of Leicester's wretchedness, he concluded in 1863: "she was murdered by persons who hoped to profit by his elevation to the throne; and Dudley himself … used private means … to prevent the search from being pressed inconveniently far." There followed the Norfolk antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

Walter Rye with ''The Murder of Amy Robsart'' in 1885: here she was first poisoned and then, that method failing, killed by violent means. Rye's main sources were Cecil's talk with de Quadra around the time of Amy Dudley's death and, again, ''Leicester's Commonwealth''. Much more scholarly and influential was an 1870 work by George Adlard, ''Amy Robsart and the Earl of Leycester'', which printed relevant letters and covertly suggested suicide as an explanation. By 1910, A.F. Pollard was convinced that the fact that Amy Robsart's death caused suspicion was "as natural as it was incredible … But a meaner intelligence than Elizabeth's or even Dudley's would have perceived that murder would make the rmarriage impossible."

Modern theories

The coroner's report came to light in

The coroner's report came to light in The National Archives

National archives are central archives maintained by countries. This article contains a list of national archives.

Among its more important tasks are to ensure the accessibility and preservation of the information produced by governments, both ...

in 2008 and is compatible with an accidental fall as well as suicide or other violence. In the absence of the forensic

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal p ...

findings of 1560, it was often assumed that a simple accident could not be the explanation—on the basis of near-contemporary tales that Amy Dudley was found at the bottom of a short flight of stairs with a broken neck, her headdress still standing undisturbed "upon her head",Jenkins 2002 p. 65 a detail that first appeared as a satirical remark in ''Leicester's Commonwealth'' and has ever since been repeated for a fact. To account for such oddities and evidence that she was ill, it was suggested in 1956 by Ian Aird, a professor of medicine, that Amy Dudley might have suffered from breast cancer, which through metastatic

Metastasis is a pathogenic agent's spread from an initial or primary site to a different or secondary site within the host's body; the term is typically used when referring to metastasis by a cancerous tumor. The newly pathological sites, then, ...

cancerous

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bl ...

deposits in the spine, could have caused her neck to break under only limited strain, such as a short fall or even just coming down the stairs. This explanation has gained wide acceptance.

Another popular theory has been that Amy Dudley took her own life; because of illness or depression, her melancholy and "desperation" being traceable in some sources. As further arguments for suicide have been forwarded the fact that she insisted on sending her servants away and that her maid Picto, Thomas Blount, and perhaps Robert Dudley himself alluded to the possibility.

A few modern historians have considered murder as an option. Alison Weir

Alison Weir ( Matthews; born 1951) is a British author and public historian. She primarily writes about the history of English royal women and families, in the form of biographies that explore their historical setting. She has also written nu ...

has tentatively suggested William Cecil as organizer of Amy Dudley's death on the grounds that, if Amy was mortally ill, he had the strongest murder motive and that he was the main beneficiary of the ensuing scandal. Against this idea it has been argued that he would not have risked damaging Elizabeth's reputation nor his own position. The notion of Sir Richard Verney killing Amy Robsart after long and fruitless efforts to poison her (with and without his master's knowledge) has been revived by George Bernard and by Chris Skidmore

Christopher James Skidmore, (born 17 May 1981) is a British politician, and author of popular history. He served as Minister of State for Universities, Science, Research and Innovation from December 2018 to July 2019, and from September 2019 ...

on the basis that Verney appears in both the c. 1563 chronicle by John Hales (also called ''Journal of Matters of State'') and the 1584 libel ''Leicester's Commonwealth''. This coincidence has as often been evaluated as no more than a tradition of gossip, poison being a stock-in-trade accusation in the 16th century.

That Robert Dudley might have influenced the jury has been argued by George Bernard, Susan Doran

Susan Doran is a British historian whose primary studies surround the reign of Elizabeth I, in particular the theme of marriage and succession. She has published and edited sixteen books, notably ''Elizabeth I and Religion, 1558-1603'', ''Monarc ...

, and by Chris Skidmore. The foreman, Sir Richard Smith (mayor of Abingdon in 1564/1565), had been a household servant of Princess Elizabeth and is described as a former "Queen's man" and a "lewd" person in Hales' 1563 chronicle, while Dudley gave a "Mr. Smith", also a "Queen's man", a present of some stuffs to make a gown from in 1566; six years after the inquest. It has, however, not been established that Sir Richard Smith and the "Mr. Smith" of 1566 are one and the same person, Smith being a "very common" name. Susan Doran has pointed out that any interference with the jury could be as easily explained by the desire to cover up a suicide rather than a murder.

Most modern historians have exonerated Robert Dudley from murder or a cover-up.Doran 1996 p. 44 Apart from alternatives for a murder plot as causes for Amy Robsart's death, his correspondence with Thomas Blount and William Cecil in the days following has been cited as proofs of his innocence; the letters, which show signs of an agitated mind, making clear his bewilderment and unpreparedness. It has also been judged as highly unlikely that he would have orchestrated the death of his wife in a manner which laid him open to such a foreseeable scandal.Weir 1999 p. 107; Wilson 2005 p. 275; Chamberlin 1939 p. 40

See also

*Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I of England has inspired artistic and cultural works for over four centuries. The following lists cover various media, enduring works of high art, and recent representations in popular culture, film and fiction. The entries represent por ...

* List of unsolved deaths

This list of unsolved deaths includes well-known cases where:

* The cause of death could not be officially determined.

* The person's identity could not be established after they were found dead.

* The cause is known, but the manner of death (homi ...

Footnotes

Citations

References

* Adams, Simon (ed.) (1995): ''Household Accounts and Disbursement Books of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, 1558–1561, 1584–1586'' Cambridge University Press * Adams, Simon (2002): ''Leicester and the Court: Essays in Elizabethan Politics'' Manchester University Press * Adams, Simon (2008)"Dudley, Robert, earl of Leicester (1532/3–1588)"

''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' online edn. May 2008 (subscription required) Retrieved 2010-04-03

* Adams, Simon (2011)"Dudley, Amy, Lady Dudley (1532–1560)"

''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' online edn. January 2011 (subscription required) Retrieved 2012-07-04

* Adams, Simon, Ian Archer, and G.W. Bernard (eds.) (2003): in Ian Archer (ed.): ''Religion, Politics, and Society in Sixteenth-Century England'' pp. 35–122 Cambridge University Press

* Bernard, George (2000): ''Power and Politics in Tudor England'' Ashgate

* Chamberlin, Frederick (1939): ''Elizabeth and Leycester'' Dodd, Mead & Co.

* Doran, Susan (1996): ''Monarchy and Matrimony: The Courtships of Elizabeth I'' Routledge

* Doran, Susan (2003): ''Queen Elizabeth I'' British Library

* Gristwood, Sarah (2007): ''Elizabeth and Leicester: Power, Passion, Politics'' Viking

* Haigh, Christopher (2000): ''Elizabeth I'' Longman

* Haynes, Alan (1987): ''The White Bear: The Elizabethan Earl of Leicester'' Peter Owen

* Historical Manuscripts Commission (ed.) (1883)''Calendar of the Manuscripts of ... The Marquess of Salisbury ... Preserved at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire''

Vol. I HMSO * Historical Manuscripts Commission (ed.) (1911)

''Report on the Pepys Manuscripts Preserved at Magdalen College, Cambridge''

HMSO * Ives, Eric (2009): ''Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery'' Wiley-Blackwell * Jenkins, Elizabeth (2002): ''Elizabeth and Leicester'' The Phoenix Press * Loades, David (1996): ''John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland 1504–1553'' Clarendon Press * Loades, David (2004): ''Intrigue and Treason: The Tudor Court, 1547–1558'' Pearson/Longman * Skidmore, Chris (2010): ''Death and the Virgin: Elizabeth, Dudley and the Mysterious Fate of Amy Robsart'' Weidenfeld & Nicolson * Weir, Alison (1999): ''The Life of Queen Elizabeth I'' Ballantine Books * Wilson, Derek (1981): ''Sweet Robin: A Biography of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester 1533–1588'' Hamish Hamilton * Wilson, Derek (2005): ''The Uncrowned Kings of England: The Black History of the Dudleys and the Tudor Throne'' Carroll & Graf

External links

* George Adlard''Amye Robsart and the Earl of Leycester''

(1870) * Peggy Inman

Cumnor History Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Robsart, Amy 1532 births 1560 deaths 16th-century English women

Amy

Amy is a female given name, sometimes short for Amanda, Amelia, Amélie, or Amita. In French, the name is spelled ''" Aimée"''.

People A–E

* Amy Acker (born 1976), American actress

* Amy Vera Ackman, also known as Mother Giovanni (1886– ...

People from Wymondham

People from Vale of White Horse (district)

Unsolved deaths

Wives of knights