American Protective League on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The American Protective League (1917-1919) was an organization of private citizens sponsored by the

The American Protective League (1917-1919) was an organization of private citizens sponsored by the

At its zenith, the American Protective League claimed 250,000 dues-paying members in 600 cities.Linfield, 38 It was claimed that 52 million Americans — approximately half of the country's population — lived in communities in which the APL maintained an active presence.

The national headquarters of the APL was established in Washington, D.C., with Briggs installed as the Chairman of the governing National Board of Directors.''World's Work,'' 394 Charles Daniel Frey, of

At its zenith, the American Protective League claimed 250,000 dues-paying members in 600 cities.Linfield, 38 It was claimed that 52 million Americans — approximately half of the country's population — lived in communities in which the APL maintained an active presence.

The national headquarters of the APL was established in Washington, D.C., with Briggs installed as the Chairman of the governing National Board of Directors.''World's Work,'' 394 Charles Daniel Frey, of

''The Web: A Revelation of Patriotism.''

Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1919. The authorized official history of the APL. * ; the main scholarly study * * Kennedy, David M. ''Over Here: The First World War and American Society.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. * Linfield, Michael. ''Freedom Under Fire: U.S. Civil Liberties in Times of War.'' Boston: South End Press, 1990. * Peterson, H. C., & Gilbert C. Fite. ''Opponents of war, 1917-1918'' (U of Wisconsin Press, 1957)

online

* Pietrusza, David. ''1920: The Year of Six Presidents.'' New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007. * Thomas, William H., Jr. ''Unsafe for Democracy: World War I and the U.S. Justice Department's Covert Campaign to Suppress Dissent.'' Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008. *

Fighting Germany's Spies: VIII: The American Protective League

" ''The World's Work,'' vol. 36, no. 4 (August 1918), pp. 393–401.

Social Conflict and Control, Protest and Repression (USA)

, in

* Brown, Charlene Fletcher

Palmer Raids

, in

* Thomas, William H.

Bureau of Investigation

, in

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20100213160911/http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/mss/biltmore_industries/07_charities_organizations/american_protective_league/jpeg/apl002mod.jpg A.M. Briggs letter of 10 Dec 1917]

Meagan English "The New Everyman"

{{Authority control History of the Industrial Workers of the World American vigilantes Organizations established in 1917 1919 disestablishments United States home front during World War I 1917 establishments in the United States Anti-communist organizations in the United States

The American Protective League (1917-1919) was an organization of private citizens sponsored by the

The American Protective League (1917-1919) was an organization of private citizens sponsored by the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United Stat ...

that worked with Federal law enforcement agencies during the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

era. Its mission to identify suspected German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

sympathizers and also to counteract the activities of radicals, anarchists, anti-war activists, and left-wing labor and political organizations. At its zenith, the APL claimed 250,000 members in 600 cities.

Organizational history

Founding

The APL was formed in 1917 by A. M. Briggs, a wealthy Chicago advertising executive. Briggs believed the Department of Justice was severely understaffed in the field of counterintelligence in the new wartime environment. He proposed a new volunteer auxiliary, with participants to be neither paid nor to benefit from expense accounts.''World's Work,'' 395 Briggs was given authority to proceed with his plan by the Department of Justice on March 22, 1917 and byPresident Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

and his cabinet on March 30, 1917 and the American Protective League (APL) was born.

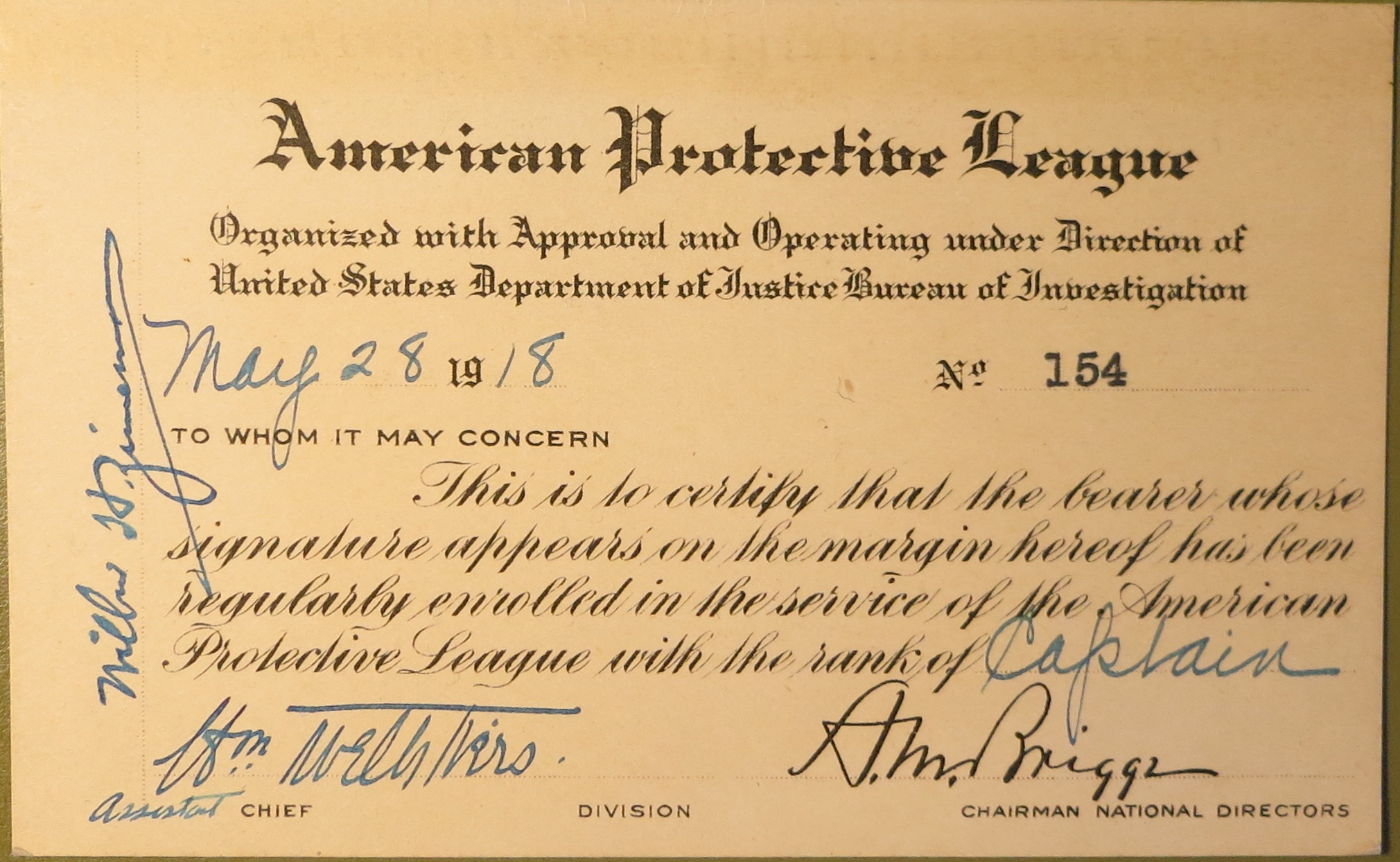

Although technically a private organization, the APL nevertheless was the beneficiary of semi-official status. The group received the formal approval from Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Thomas Gregory, who authorized the APL to carry on its letterhead the words "Organized with the Approval and Operating under the Direction of the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United Stat ...

, Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

."

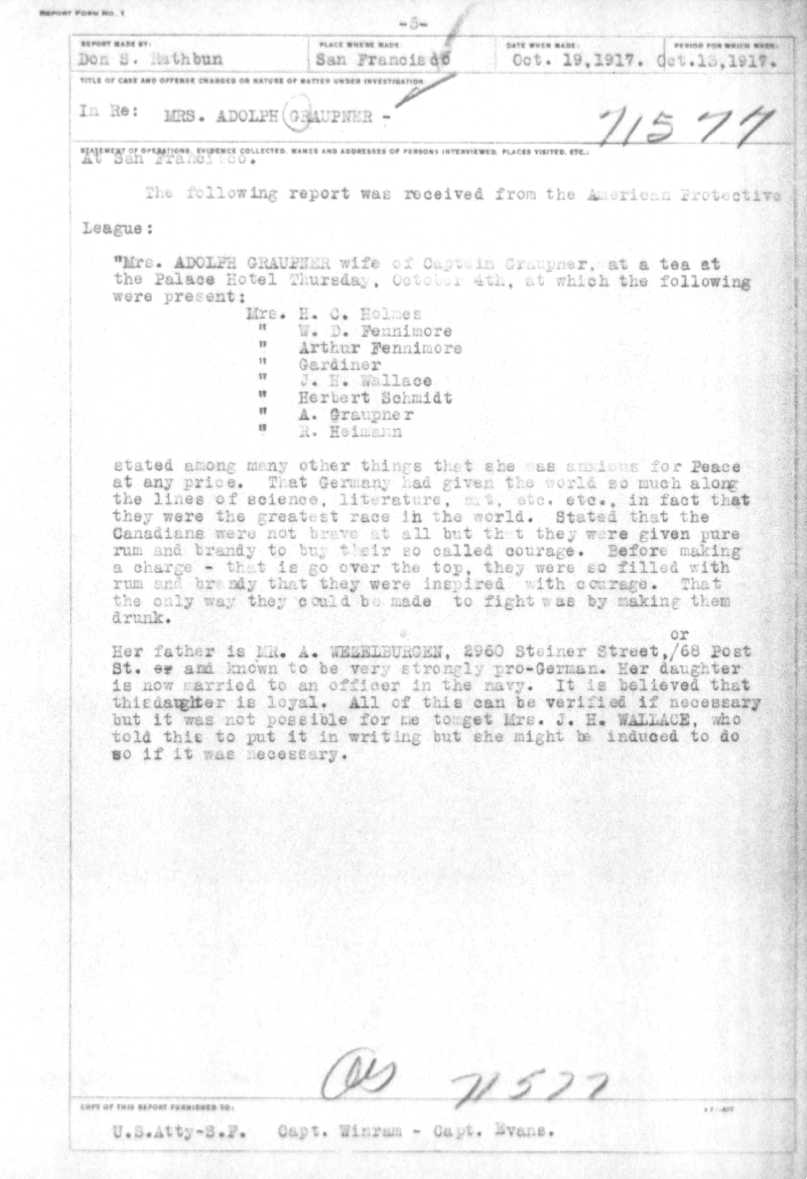

Under this directive, the APL worked with the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) — precursor to the FBI — which gathered information for U.S. District Attorneys. APL assistance was welcomed by the BOI, which in 1915 had only 219 field agents, without direct statutory authorization to carry weapons or to make general arrests.Glen L. Roberts, "APL and the BOI," ''Full Disclosure Magazine.'' Thus the author of a letter to the ''New York Times'' claimed membership in the APL and described it as "a volunteer unpaid auxiliary of the Department of Justice" in which he and his colleagues "have been acting upon cases assigned by the Department of Justice, Military Intelligence, State Department, Civil Service, Provost Marshal General, etc."

APL members sometimes wore badges suggesting a quasi-official status: "American Protective League –Secret Service." The Attorney General boasted of the manpower they provided: "I have today several hundred thousand private citizens... assisting the heavily overworked Federal authorities in keeping an eye on disloyal individuals and making reports of disloyal utterances."

In a letter to Briggs, the Justice Department told the APL that it was not only "of great importance prior to our entering the war, it became of vastly greater importance after that step had been taken." The government had been receiving complaints of disloyalty and enemy activities, and while the Bureau of Investigation was doing its best to contain the situation, the letter continued, the Protective League served as an auxiliary force to put a stop to corruption within the borders of the United States.

Membership and structure

At its zenith, the American Protective League claimed 250,000 dues-paying members in 600 cities.Linfield, 38 It was claimed that 52 million Americans — approximately half of the country's population — lived in communities in which the APL maintained an active presence.

The national headquarters of the APL was established in Washington, D.C., with Briggs installed as the Chairman of the governing National Board of Directors.''World's Work,'' 394 Charles Daniel Frey, of

At its zenith, the American Protective League claimed 250,000 dues-paying members in 600 cities.Linfield, 38 It was claimed that 52 million Americans — approximately half of the country's population — lived in communities in which the APL maintained an active presence.

The national headquarters of the APL was established in Washington, D.C., with Briggs installed as the Chairman of the governing National Board of Directors.''World's Work,'' 394 Charles Daniel Frey, of Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, served as the national director of the American Protective League.

In addition to its regular geographically-based network, the APL attempted to organize secret units inside factories producing clothing and war materiel, with a view to identification of those advancing "discouraging disloyalty" or engaging in pro-German activities.''World's Work,'' 396 Suspects would be reported within the APL organization, which would then make use of its broader network in the community to investigate the activities of these individuals after working hours, if deemed so necessary.

Activities

Teams of APL members conducted numerous raids and surveillance activities aimed at those who failed to register for the draft and at German immigrants who were suspected of sympathies for Germany. APL headquarters and the Justice Department in Washington often lost control over field operations, to the point that U.S. Attorneys and BOI agents, assisted by cadres of volunteers from the APL and other similar patriotic auxiliaries, pursued suspects of disloyalty on their own initiative and in their own manner. APL members "spotted violators of food and gasoline regulations, rounded up draft evaders in New York, disrupted Socialist meetings in Cleveland, broke strikes, ndthreatened union men with immediate induction into the army." In the most extraordinary cooperative action, thousands of APL members joined authorities inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

for three days of checking registration cards. This resulted in more than 75,000 arrests, though fewer than 400 of those arrested were shown to be guilty of anything more than failing to carry their cards. APL agents, many of them female, worked undercover in factories and attended union meetings in hope of uncovering saboteurs and other enemies of the war effort.

APL members were accused of acting as vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

s, allegedly violating the civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

of American citizens, including so-called "anti-slacker raids" designed to round up men who had not registered for the draft. The APL was also accused of illegally detaining citizens associated with anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

, labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

, and pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

movements.

An APL report on its actions in the Northwest for five months in 1918 showed that among its 25 activities, its largest effort (some 10% of its activity), was in disrupting the IWW. Some IWW members had been involved in violent labor disputes and bomb plots against U.S. businessmen and government officials. In turn, the IWW alleged that APL members burgled and vandalized IWW offices and harassed IWW members.

Criticism

During World War I, the APL was joined by many similar groups formed by civilians to fight against foreign infiltration and sabotage. The "Anti Yellow Dog League" was a youth organization composed of school boys over the age of ten, who sought out disloyal persons. Such leagues and societies branched across the nation. President Wilson knew of the APL's activities and had misgivings about their methods. He wrote to Attorney General Gregory expressing his concern: "It would be dangerous to have such an organization operating in the United States, and I wonder if there is any way in which we could stop it?" But he deferred to Gregory's judgment and took no action to curtail the APL, officially approving the organization along with his cabinet. The APL also worked with the army's Military Intelligence Division (MID), the government's principal investigatory agency in this period. When the relationship between the APL and the MID became public early in 1919, the revelations embarrassedSecretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Newton D. Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

. Baker tried to end the War Department's use of volunteer spies.

Disbandment

After theArmistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

ended the war, Attorney General Gregory credited the APL with the defeat of German spies and propaganda. He claimed that his Department still required the APL's services as enemy nations sought to weaken American resolve during the peace negotiations, especially as newly democratic Germany sought kindlier treatment than its predecessor government might have expected.

A. Mitchell Palmer succeeded Gregory as Attorney General on 5 March 1919. Before assuming office, he had opposed the APL activities. One of Palmer's first acts was to release 10,000 aliens of German ancestry who had been taken into government custody during the war. He stopped accepting intelligence gathered by the APL. He ordered some APL agents arrested. He also refused to share information in his APL-provided files when Ohio Governor James M. Cox

James Middleton Cox (March 31, 1870 July 15, 1957) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 46th and 48th governor of Ohio, and a two-term U.S. Representative from Ohio. As the Democratic nominee for President of the United ...

requested it. He called the APL materials "gossip, hearsay information, conclusions, and inferences" and added that "information of this character could not be used without danger of doing serious wrong to individuals who were probably innocent." In March 1919, when some in Congress and the press were urging him to reinstate the Justice Department's wartime relationship with the APL, he told reporters that "its operation in any community constitutes a grave menace."

A few months after the Armistice, the League officially disbanded, even as its members insisted they could serve as they had earlier in wartime against America's post-war enemies, "these bomb fiends, Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

i, IWW's and other fiends." The publication of the organization's story as ''The Web: A Revelation of Patriotism'' was an attempt to revive its fortunes as well. That volume by Emerson Hough

Emerson Hough (June 28, 1857 – April 30, 1923) was an American author best known for writing western stories and historical novels. His early works included Singing Mouse Stories and Story of the Cowboy. He was well known for his 1902 historic ...

, an author of Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

novels, called for a program of "selective immigration, deportation of un-Americans, and denaturalization of 'disloyal' citizens and anarchists." It said: "We must purify the source of America's population and keep it pure." On June 3, 1919, the ''Washington Post'' called for the revival of the APL to fight anarchists.

The APL survived as a series of local organizations under other names, such as the Patriotic American League (Chicago) and the Loyalty League (Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

). New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

members served as investigators for New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

's Lusk Committee

The Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities, popularly known as the Lusk Committee, was formed in 1919 by the New York State Legislature to investigate individuals and organizations in New York State suspected of sedition.

...

investigation of radicals and political dissenters. APL members continued to provide information and manpower to the Department of Justice, notably during the Palmer raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchists ...

of January 1920. In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

recruited members from the Southern branches of the APL. For years following the war, J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

's General Intelligence Unit in the Justice Department drew on the APL for information about radicals.Hagedorn, 332

See also

*Alexander Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer (May 4, 1872 – May 11, 1936), was an American attorney and politician who served as the 50th United States attorney general from 1919 to 1921. He is best known for overseeing the Palmer Raids during the Red Scar ...

*National Security League

The National Security League (NSL) was an American patriotic, nationalistic, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that supported a greatly-expanded military based upon universal service, the naturalization and Americanization of immigrants, Ame ...

*American Defense Society

The American Defense Society (ADS) was a nationalist American political group founded in 1915. The ADS was formed to advocate for American intervention in World War I against the German Empire. The group later stood in opposition to the Bolshevi ...

*Ralph Van Deman

Ralph Henry Van Deman (1865–1952) was a United States Army officer, sometimes described as "the father of American military intelligence." He is in the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.

Early career

Van Deman was born in Delaware, Ohio, a ...

Notes

Further reading

* Ackerman, Kenneth D. ''Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties.'' New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007. * Coben, Stanley. ''A. Mitchell Palmer: Politician.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1963. * Christopher Cappozolla, ''Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. * Fischer, Nick. "The American Protective League and the Australian Protective League — Two Responses to the Threat of Communism, c. 1917–1920," ''American Communist History,'' vol. 10, no. 2 (2011), pp. 133–149. * Hagedorn, Ann. ''Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007. * Higham, John. ''Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925.'' Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002. * Hough, Emerson''The Web: A Revelation of Patriotism.''

Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1919. The authorized official history of the APL. * ; the main scholarly study * * Kennedy, David M. ''Over Here: The First World War and American Society.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. * Linfield, Michael. ''Freedom Under Fire: U.S. Civil Liberties in Times of War.'' Boston: South End Press, 1990. * Peterson, H. C., & Gilbert C. Fite. ''Opponents of war, 1917-1918'' (U of Wisconsin Press, 1957)

online

* Pietrusza, David. ''1920: The Year of Six Presidents.'' New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007. * Thomas, William H., Jr. ''Unsafe for Democracy: World War I and the U.S. Justice Department's Covert Campaign to Suppress Dissent.'' Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008. *

Fighting Germany's Spies: VIII: The American Protective League

" ''The World's Work,'' vol. 36, no. 4 (August 1918), pp. 393–401.

External links

* Strauss, LonSocial Conflict and Control, Protest and Repression (USA)

, in

* Brown, Charlene Fletcher

Palmer Raids

, in

* Thomas, William H.

Bureau of Investigation

, in

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20100213160911/http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/mss/biltmore_industries/07_charities_organizations/american_protective_league/jpeg/apl002mod.jpg A.M. Briggs letter of 10 Dec 1917]

Meagan English "The New Everyman"

{{Authority control History of the Industrial Workers of the World American vigilantes Organizations established in 1917 1919 disestablishments United States home front during World War I 1917 establishments in the United States Anti-communist organizations in the United States