Amel-Marduk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Amel-Marduk ( ''Amēl-Marduk'', meaning "man of

''Amēl-Marduk'', meaning "man of

Amel-Marduk was the successor of his father,

Amel-Marduk was the successor of his father,  ), who states that he was imprisoned because of a conspiracy against him. According to the

), who states that he was imprisoned because of a conspiracy against him. According to the

Babylonian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-s ...

:  ''Amēl-Marduk'', meaning "man of

''Amēl-Marduk'', meaning "man of Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

"), also known as Awil-Marduk, or under the biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of ...

rendition of his name, Evil-Merodach (Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

: , ''ʾÉwīl Mərōḏaḵ''), was the third king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

, ruling from 562 BC until his overthrow and murder in 560 BC. He was the successor of Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

(605–562 BC). On account of the small number of surviving cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

sources, little is known of Amel-Marduk's reign and actions as king.

Amel-Marduk, originally named Nabu-shum-ukin, was not Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son, nor the oldest living son at the time of his appointment as crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the w ...

and heir. It is not clear why Amel-Marduk was appointed by his father as successor, particularly since there appears to have been altercations between the two, possibly involving an attempt by Amel-Marduk to take the throne while his father was still alive. After the conspiracy, Amel-Marduk was imprisoned, possibly together with Jeconiah, the captured king of Judah. Nabu-shum-ukin changed his name to Amel-Marduk upon his release, possibly in reverence of the god Marduk to whom he had prayed.

Amel-Marduk is remembered mainly for releasing Jeconiah after 37 years of imprisonment. Amel-Marduk is also known to have conducted some building work in Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, and possibly elsewhere, though the extent of his projects is unclear. The Babylonians appear to have resented his rule, as Babylonian sources from after his reign describe him as incompetent. In 560 BC, he was overthrown and murdered by his brother-in-law Neriglissar who thereafter ruled as king.

Background

Amel-Marduk was the successor of his father,

Amel-Marduk was the successor of his father, Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

(605–562 BC). It seems that the succession to Nebuchadnezzar was troublesome and that the king's last years were prone to political instability. In one of the inscriptions written very late in his reign, after Nebuchadnezzar had already ruled for forty years, the king affirms that he had been chosen for kingship by the gods before he had even been born. Stressing divine legitimacy in such a fashion was usually only done by usurpers, or if there were political problems with his intended successor. Given that Nebuchadnezzar had been king for several decades, and had been the legitimate heir of his predecessor, the first option seems unlikely.

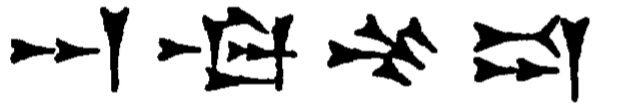

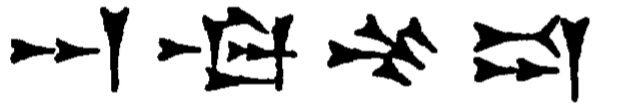

Amel-Marduk was chosen as heir during his father's reign and is attested as crown prince in 566 BC. Amel-Marduk was not Nebuchadnezzar's oldest son—another of Nebuchadnezzar's sons, Marduk-nadin-ahi, is attested in Nebuchadnezzar's third year as king (602/601 BC) as an adult in charge of his own lands. Given that Amel-Marduk is attested considerably later, it is probable that Marduk-nadin-ahi was Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son and legitimate heir, making the selection of Amel-Marduk unclear, particularly since Marduk-nadin-ahi is attested as living until as late as 563 BC. Additionally, evidence of altercations between Nebuchadnezzar and Amel-Marduk makes his selection as heir seem even more improbable. In one text, Nebuchadnezzar and Amel-Marduk are both implicated in some kind of conspiracy, with one of the two accused of bad conduct against the temples and people:

The inscription contains accusations, though it is unclear to whom they are directed, concerning the desecration of holy places and the exploitation of the populace—failures in the two main responsibilities of the king of Babylon. The accused is afterwards stated to have cried and prayed to Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

, Babylon's national deity.

Another text from late in Nebuchadnezzar's reign contains a prayer by an imprisoned son of Nebuchadnezzar named Nabu-shum-ukin ( ), who states that he was imprisoned because of a conspiracy against him. According to the

), who states that he was imprisoned because of a conspiracy against him. According to the Leviticus Rabbah

Leviticus Rabbah, Vayikrah Rabbah, or Wayiqra Rabbah is a homiletic midrash to the Biblical book of Leviticus (''Vayikrah'' in Hebrew). It is referred to by Nathan ben Jehiel (c. 1035–1106) in his ''Arukh'' as well as by Rashi (1040–1105) ...

, a 5th–7th-century AD Midrashic text, Amel-Marduk was imprisoned by his father alongside the captured Judean king Jeconiah (also known as Jehoiachin) because some of the Babylonian officials had proclaimed him king while Nebuchadnezzar was away. The Assyriologist Irving Finkel

Irving Leonard Finkel (born 1951) is a British philologist and Assyriologist. He is the Assistant Keeper of Ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures in the Department of the Middle East in the British Museum, where he specialises in c ...

argued in 1999 that Nabu-shum-ukin was the same person as Amel-Marduk, who changed his name to "man of Marduk" once he was released as reverence towards the god to whom he had prayed. Finkel's conclusions have been accepted as convincing by other scholars, and would also explain the previous text, perhaps relating to the same incidents. The '' Chronicles of Jerahmeel'', a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

work on history possibly written in the 12th century AD, erroneously states that Amel-Marduk was Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son, but that he was sidelined by his father in favour of his brother, 'Nebuchadnezzar the Younger' (a fictional figure not attested in any other source), and was thus imprisoned together with Jeconiah until the death of Nebuchadnezzar the Younger, after which Amel-Marduk was made king.

Considering the available evidence, it is possible that Nebuchadnezzar saw Amel-Marduk as an unworthy heir and sought to replace him with another son. Why Amel-Marduk nevertheless became king is not clear. Regardless, Amel-Marduk's administrative duties probably began before he became king, during the last few weeks or months of his father's reign when Nebuchadnezzar was ill and dying. The last known tablet dated to Nebuchadnezzar's reign, from Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Muthanna Governorate, Al ...

, is dated to the same day, 7 October, as the first known tablet of Amel-Marduk, from Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

.

Reign

Very fewcuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

sources survive from Amel-Marduk's reign, and as such, almost nothing is known of his accomplishments. Despite being the legitimate successor of Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

, Amel-Marduk was seemingly met with opposition from the very beginning of his rule, as indicated by the brevity of his tenure as king and by his negative portrayal in later sources. The later Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

-era Babylonian writer and astronomer Berossus wrote that Amel-Marduk "ruled capriciously and had no regard for the laws" and a cuneiform propaganda text states that he neglected his family, that officials refused to carry out his orders, and that he solely concerned himself with veneration and worship of Marduk. Whether the opposition towards Amel-Marduk resulted from his earlier attempt at conspiracy against his father, tension between different factions of the royal family (given that he was not the oldest son), or from his own mismanagement as king, is not certain. Little is known of Amel-Marduk's own immediate family, i.e., his wife and potential children. No sons of Amel-Marduk are known, but he had at least one daughter named Indû. The ''Chronicles of Jerahmeel'' ascribes three sons to Amel-Marduk: Regosar, Lebuzer Dukh and Nabhar, though it seems the author confused Amel-Marduk's successors for his sons (respectively, Neriglissar, Labashi-Marduk

Labashi-Marduk (Babylonian cuneiform: or , meaning "O Marduk, may I not come to shame") was the fifth and penultimate king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling in 556 BC. He was the son and successor of Neriglissar. Though classical authors suc ...

and Nabonidus

Nabonidus (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-naʾid'', meaning "May Nabu be exalted" or "Nabu is praised") was the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 556 BC to the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in ...

).

One of his inscriptions suggests that he renovated the Esagila in Babylon, and the Ezida in Borsippa, but no concrete archaeological or textual evidence exists to confirm that work was actually done at these temples. Some bricks and paving stones in Babylon bear his name, indicating that some building work was completed at Babylon during his brief tenure as king.

The Bible states that Amel-Marduk freed Jeconiah, king of Judah, after 37 years of imprisonment in Babylon, the only concrete political act attributed to Amel-Marduk in any extant source. Though such acts of clemency are known from accession ceremonies, and in this case may have been connected to the celebration of the Babylonian New Year's Festival, the specific reason for Jeconiah's release is not known. Suggested reasons include to win favour with the population of Jewish deportees in Babylonia, or that Amel-Marduk and Jeconiah may have become friends during their imprisonment. Later Jewish tradition held that the release was a deliberate reversal of Nebuchadnezzar's policy (having destroyed the Kingdom of Judah), though there is no indication that Amel-Marduk made any attempt to restore Judah. Despite this, Jewish contemporaries of Amel-Marduk likely hoped that Jeconiah's release was the first step in a restoration of Judah, given that Amel-Marduk also released Baalezer, the captured king of Tyre, and restored him to his throne. The release of Jeconiah is narrated in 2 Kings 25:27–30, and in the ''Chronicles of Jerahmeel'', both sources referring to Amel-Marduk as Evil-Merodach. The ''Chronicles of Jerahmeel'' narrates the release of Jeconiah as follows:

Amel-Marduk's reign abruptly ended in August 560 BC, after barely two years as king, when he was deposed and murdered by Neriglissar, his brother-in-law, who then claimed the throne. The last document from the reign of Amel-Marduk is a contract dated to 7 August 560 BC, written in Babylon. Four days later, documents dated to Neriglissar are known from both Babylon and Uruk. Based on increased economic activity attributed to him in the capital, Neriglissar was at Babylon at the time of the usurpation. It is likely that the conflict between Amel-Marduk and Neriglissar was a result of inter-family discord rather than some other form of rivalry. Neriglissar was married to one of Nebuchadnezzar's daughters, possibly Kashshaya. As Kashshaya is attested considerably earlier in Nebuchadnezzar's reign than Amel-Marduk (in Nebuchadnezzar's fifth year, 600/599 BC) and most of the other sons, it is possible that she was older than them. Though the gap between the earliest reference to Kashshaya and those of the sons could be accidental or coincidental; it could also be interpreted as an indication that many of the sons were the progeny of a second marriage. It is therefore possible that Neriglissar's usurpation was the result of infighting between an older, wealthier and more influential branch of the royal family (represented by Nebuchadnezzar's daughters, Kashshaya in particular) and a less well established and younger, though more legitimate, branch (represented by Nebuchadnezzar's sons, such as Amel-Marduk).

Titles

From one of his inscriptions, found on a pillar of one of Babylon's bridges, Amel-Marduk's titles read as follows: Given that few inscriptions of Amel-Marduk are known, no more elaborate versions of his titulature are known. He may also have used the title ' king of Sumer and Akkad', used by other Neo-Babylonian kings.See also

* List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sourcesReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Amel-Marduk 560 BC deaths Year of birth unknown 6th-century BC Babylonian kings 6th-century BC murdered monarchs 6th-century BC rulers Neo-Babylonian kings Monarchs of the Hebrew Bible Biblical murder victims Dethroned monarchs Male murder victims Chaldean dynasty