Alternatives to evolution by natural selection on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since Early Modern times, vitalism stood in contrast to the mechanistic explanation of biological systems started by Descartes. Nineteenth century chemists set out to disprove the claim that forming organic compounds required vitalist influence. In 1828,

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since Early Modern times, vitalism stood in contrast to the mechanistic explanation of biological systems started by Descartes. Nineteenth century chemists set out to disprove the claim that forming organic compounds required vitalist influence. In 1828,

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of body plans. Before Darwin,

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of body plans. Before Darwin,

The neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura in 1968, holds that at the molecular level most

The neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura in 1968, holds that at the molecular level most

The various alternatives to Darwinian evolution by natural selection were not necessarily mutually exclusive. The evolutionary philosophy of the American palaeontologist

The various alternatives to Darwinian evolution by natural selection were not necessarily mutually exclusive. The evolutionary philosophy of the American palaeontologist

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

and the relatedness of different groups of living things. The alternatives in question do not deny that evolutionary changes over time are the origin of the diversity of life, nor that the organisms alive today share a common ancestor from the distant past (or ancestors, in some proposals); rather, they propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change over time, arguing against mutations acted on by natural selection as the most important driver of evolutionary change.

This distinguishes them from certain other kinds of arguments that deny that large-scale evolution of any sort has taken place, as in some forms of creationism

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 't ...

, which do not propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change but instead deny that evolutionary change has taken place at all. Not all forms of creationism deny that evolutionary change takes place; notably, proponents of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution) is a theological view that God creates through laws of nature. Its religious teachings are fully compatible with the findings of modern science, including biologica ...

, such as the biologist Asa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessarily mutually excl ...

, assert that evolutionary change does occur and is responsible for the history of life on Earth, with the proviso that this process has been influenced by a god or gods in some meaningful sense.

Where the fact of evolutionary change was accepted but the mechanism proposed by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

, was denied, explanations of evolution such as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow incremen ...

, orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some g ...

, vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

, structuralism

In sociology, anthropology, archaeology, history, philosophy, and linguistics, structuralism is a general theory of culture and methodology that implies that elements of human culture must be understood by way of their relationship to a broader s ...

and mutationism (called saltationism before 1900) were entertained. Different factors motivated people to propose non- Darwinian mechanisms of evolution. Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it immoral, leaving little room for teleology

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

or the concept of progress (orthogenesis) in the development of life. Some who came to accept evolution, but disliked natural selection, raised religious objections. Others felt that evolution was an inherently progressive process that natural selection alone was insufficient to explain. Still others felt that nature, including the development of life, followed orderly patterns that natural selection could not explain.

By the start of the 20th century, evolution was generally accepted by biologists but natural selection was in eclipse. Many alternative theories were proposed, but biologists were quick to discount theories such as orthogenesis, vitalism and Lamarckism which offered no mechanism for evolution. Mutationism did propose a mechanism, but it was not generally accepted. The modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and ...

a generation later claimed to sweep away all the alternatives to Darwinian evolution, though some have been revived as molecular mechanisms for them have been discovered.

Unchanging forms

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

did not embrace either divine creation or evolution, instead arguing in his biology that each species (''eidos'') was immutable, breeding true to its ideal eternal form (not the same as Plato's theory of forms). Aristotle's suggestion in ''De Generatione Animalium

The ''Generation of Animals'' (or ''On the Generation of Animals''; Greek: ''Περὶ ζῴων γενέσεως'' (''Peri Zoion Geneseos''); Latin: ''De Generatione Animalium'') is one of the biological works of the Corpus Aristotelicum, the col ...

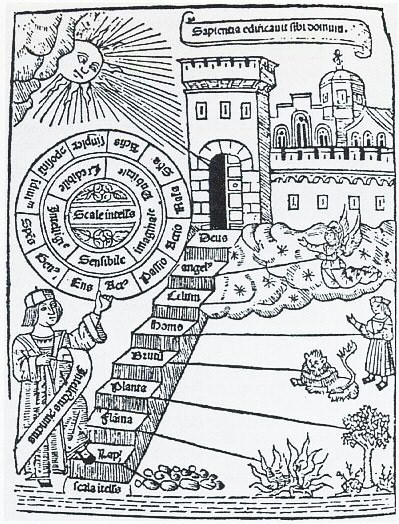

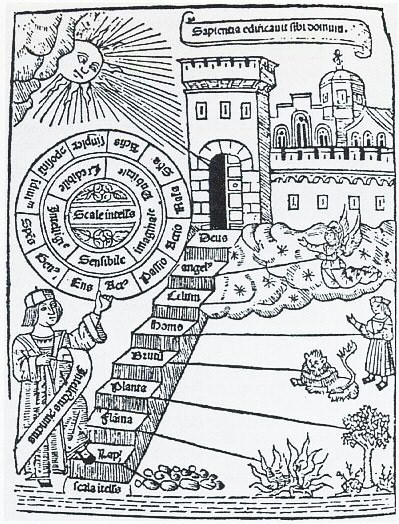

'' of a fixed hierarchy in nature - a ''scala naturae'' ("ladder of nature") provided an early explanation of the continuity of living things. Aristotle saw that animals were teleological (functionally end-directed), and had parts that were homologous with those of other animals, but he did not connect these ideas into a concept of evolutionary progress.

In the Middle Ages, Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translat ...

developed Aristotle's view into the idea of a great chain of being. The image of a ladder inherently suggests the possibility of climbing, but both the ancient Greeks and mediaeval scholastics such as Ramon Lull maintained that each species remained fixed from the moment of its creation.

By 1818, however, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

argued in his ''Philosophie anatomique'' that the chain was "a progressive series", where animals like molluscs low on the chain could "rise, by addition of parts, from the simplicity of the first formations to the complication of the creatures at the head of the scale", given sufficient time. Accordingly, Geoffroy and later biologists looked for explanations of such evolutionary change.

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

's 1812 ''Recherches sur les Ossements Fossiles'' set out his doctrine of the correlation of parts, namely that since an organism was a whole system, all its parts mutually corresponded, contributing to the function of the whole. So, from a single bone the zoologist could often tell what class or even genus the animal belonged to. And if an animal had teeth adapted for cutting meat, the zoologist could be sure without even looking that its sense organs would be those of a predator and its intestines those of a carnivore. A species had an irreducible functional complexity, and "none of its parts can change without the others changing too". Evolutionists expected one part to change at a time, one change to follow another. In Cuvier's view, evolution was impossible, as any one change would unbalance the whole delicate system.

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

's 1856 "Essay on Classification" exemplified German philosophical idealism. This held that each species was complex within itself, had complex relationships to other organisms, and fitted precisely into its environment, as a pine tree in a forest, and could not survive outside those circles. The argument from such ideal forms opposed evolution without offering an actual alternative mechanism. Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

held a similar view in Britain.

The Lamarckian social philosopher and evolutionist Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the f ...

, ironically the author of the phrase "survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, ...

" adopted by Darwin, used an argument like Cuvier's to oppose natural selection. In 1893, he stated that a change in any one structure of the body would require all the other parts to adapt to fit in with the new arrangement. From this, he argued that it was unlikely that all the changes could appear at the right moment if each one depended on random variation; whereas in a Lamarckian world, all the parts would naturally adapt at once, through a changed pattern of use and disuse.

Alternative explanations of change

Where the fact of evolutionary change was accepted by biologists butnatural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

was denied, including but not limited to the late 19th century eclipse of Darwinism, alternative scientific explanations such as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some g ...

, structuralism

In sociology, anthropology, archaeology, history, philosophy, and linguistics, structuralism is a general theory of culture and methodology that implies that elements of human culture must be understood by way of their relationship to a broader s ...

, catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow incremen ...

, vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

and theistic evolution were entertained, not necessarily separately. (Purely religious points of view such as young or old earth creationism

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 't ...

or intelligent design

Intelligent design (ID) is a pseudoscientific argument for the existence of God, presented by its proponents as "an evidence-based scientific theory about life's origins". Numbers 2006, p. 373; " Dcaptured headlines for its bold attempt to ...

are not considered here.) Different factors motivated people to propose non-Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms. Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it immoral, leaving little room for teleology

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

or the concept of progress in the development of life. Some of these scientists and philosophers, like St. George Jackson Mivart and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

, who came to accept evolution but disliked natural selection, raised religious objections. Others, such as the biologist and philosopher Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the f ...

, the botanist George Henslow

George Henslow (23 March 1835, Cambridge, UK – 30 December 1925, Bournemouth) was an Anglican curate, botanist and author. Henslow was notable for being a defender of Lamarckian evolution.

Biography

The third son of Rev. John Stevens Henslow, ...

(son of Darwin's mentor John Stevens Henslow, also a botanist), and the author Samuel Butler, felt that evolution was an inherently progressive process that natural selection alone was insufficient to explain. Still others, including the American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interes ...

and Alpheus Hyatt

Alpheus Hyatt (April 5, 1838 – January 15, 1902) was an American zoologist and palaeontologist.

Biography

Alpheus Hyatt II was born in Washington, D.C. to Alpheus Hyatt and Harriet Randolph (King) Hyatt. He briefly attended the Mary ...

, had an idealist perspective and felt that nature, including the development of life, followed orderly patterns that natural selection could not explain.

Some felt that natural selection would be too slow, given the estimates of the age of the earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

and sun (10–100 million years) being made at the time by physicists such as Lord Kelvin, and some felt that natural selection could not work because at the time the models for inheritance involved blending of inherited characteristics, an objection raised by the engineer Fleeming Jenkin in a review of ''Origin'' written shortly after its publication. Another factor at the end of the 19th century was the rise of a new faction of biologists, typified by geneticists like Hugo de Vries and Thomas Hunt Morgan, who wanted to recast biology as an experimental laboratory science. They distrusted the work of naturalists like Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

, dependent on field observations of variation, adaptation, and biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

, as being overly anecdotal. Instead they focused on topics like physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

that could be investigated with controlled experiments in the laboratory, and discounted less accessible phenomena like natural selection and adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the po ...

to the environment.

Vitalism

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since Early Modern times, vitalism stood in contrast to the mechanistic explanation of biological systems started by Descartes. Nineteenth century chemists set out to disprove the claim that forming organic compounds required vitalist influence. In 1828,

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt.

Since Early Modern times, vitalism stood in contrast to the mechanistic explanation of biological systems started by Descartes. Nineteenth century chemists set out to disprove the claim that forming organic compounds required vitalist influence. In 1828, Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler () FRS(For) Hon FRSE (31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements beryllium and yttrium in pure metallic form. He was the fi ...

showed that urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

could be made entirely from inorganic chemicals. Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

believed that fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

required whole organisms, which he supposed carried out chemical reactions found only in living things. The embryologist Hans Driesch, experimenting on sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) o ...

eggs, showed that separating the first two cells led to two complete but small blastula

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula (fro ...

s, seemingly showing that cell division did not divide the egg into sub-mechanisms, but created more cells each with the vital capability to form a new organism. Vitalism faded out with the demonstration of more satisfactory mechanistic explanations of each of the functions of a living cell or organism. By 1931, biologists had "almost unanimously abandoned vitalism as an acknowledged belief."

Theistic evolution

The American botanistAsa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessarily mutually excl ...

used the name "theistic evolution" for his point of view, presented in his 1876 book ''Essays and Reviews Pertaining to Darwinism''. He argued that the deity supplies beneficial mutations to guide evolution. St George Jackson Mivart

St. George Jackson Mivart (30 November 1827 – 1 April 1900) was an English biologist. He is famous for starting as an ardent believer in natural selection who later became one of its fiercest critics. Mivart attempted to reconcile ...

argued instead in his 1871 ''On the Genesis of Species'' that the deity, equipped with foreknowledge, sets the direction of evolution by specifying the (orthogenetic) laws that govern it, and leaves species to evolve according to the conditions they experience as time goes by. The Duke of Argyll set out similar views in his 1867 book ''The Reign of Law''. According to the historian Edward Larson, the theory failed as an explanation in the minds of late 19th century biologists as it broke the rules of methodological naturalism

In philosophy, naturalism is the idea or belief that only natural laws and forces (as opposed to supernatural ones) operate in the universe.

According to philosopher Steven Lockwood, naturalism can be separated into an ontological sense and a me ...

which they had grown to expect. Accordingly, by around 1900, biologists no longer saw theistic evolution as a valid theory. In Larson's view, by then it "did not even merit a nod among scientists." In the 20th century, theistic evolution could take other forms, such as the orthogenesis of Teilhard de Chardin.

Orthogenesis

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

openly spiritual, others such as Theodor Eimer's apparently simply biological. These theories often combined orthogenesis with other supposed mechanisms. For example, Eimer believed in Lamarckian evolution, but felt that internal laws of growth determined which characteristics would be acquired and would guide the long-term direction of evolution.

Orthogenesis was popular among paleontologists such as Henry Fairfield Osborn. They believed that the fossil record showed unidirectional change, but did not necessarily accept that the mechanism driving orthogenesis was teleological (goal-directed). Osborn argued in his 1918 book ''Origin and Evolution of Life'' that trends in Titanothere

Brontotheriidae is a family of extinct mammals belonging to the order Perissodactyla, the order that includes horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs. Superficially, they looked rather like rhinos, although they were actually more closely related to h ...

horns were both orthogenetic and non- adaptive, and could be detrimental to the organism. For instance, they supposed that the large antlers of the Irish elk had caused its extinction.

Support for orthogenesis fell during the modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and ...

in the 1940s when it became apparent that it could not explain the complex branching patterns of evolution revealed by statistical analysis of the fossil record. Work in the 21st century has supported the mechanism and existence of mutation-biased adaptation (a form of mutationism), meaning that constrained orthogenesis is now seen as possible. Moreover, the self-organizing processes involved in certain aspects of embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

often exhibit stereotypical morphological outcomes, suggesting that evolution will proceed in preferred directions once key molecular components are in place.

Lamarckism

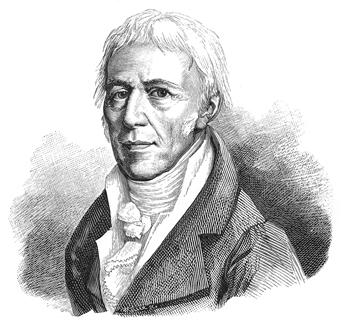

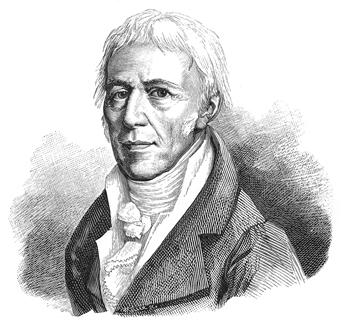

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

's 1809 evolutionary theory, transmutation of species

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a term used ...

, was based on a progressive (orthogenetic) drive toward greater complexity. Lamarck also shared the belief, common at the time, that characteristics acquired during an organism's life could be inherited by the next generation, producing adaptation to the environment. Such characteristics were caused by the use or disuse of the affected part of the body. This minor component of Lamarck's theory became known, much later, as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

. Darwin included ''Effects of the increased Use and Disuse of Parts, as controlled by Natural Selection'' in ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', giving examples such as large ground feeding birds getting stronger legs through exercise, and weaker wings from not flying until, like the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds of the genus ''Struthio'' in the order Struthioniformes, part of the infra-class Palaeognathae, a diverse group of flightless birds also known as ratites that includes the emus, rheas, and kiwis. There ...

, they could not fly at all. In the late 19th century, neo-Lamarckism was supported by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new s ...

, the American paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

s Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interes ...

and Alpheus Hyatt

Alpheus Hyatt (April 5, 1838 – January 15, 1902) was an American zoologist and palaeontologist.

Biography

Alpheus Hyatt II was born in Washington, D.C. to Alpheus Hyatt and Harriet Randolph (King) Hyatt. He briefly attended the Mary ...

, and the American entomologist

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as ara ...

Alpheus Packard. Butler and Cope believed that this allowed organisms to effectively drive their own evolution. Packard argued that the loss of vision in the blind cave insects he studied was best explained through a Lamarckian process of atrophy through disuse combined with inheritance of acquired characteristics. Meanwhile, the English botanist George Henslow

George Henslow (23 March 1835, Cambridge, UK – 30 December 1925, Bournemouth) was an Anglican curate, botanist and author. Henslow was notable for being a defender of Lamarckian evolution.

Biography

The third son of Rev. John Stevens Henslow, ...

studied how environmental stress affected the development of plants, and he wrote that the variations induced by such environmental factors could largely explain evolution; he did not see the need to demonstrate that such variations could actually be inherited. Critics pointed out that there was no solid evidence for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Instead, the experimental work of the German biologist August Weismann resulted in the germ plasm theory of inheritance, which Weismann said made the inheritance of acquired characteristics impossible, since the Weismann barrier would prevent any changes that occurred to the body after birth from being inherited by the next generation.

In modern epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are ...

, biologists observe that phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (biology), morphology or physical form and structure, its Developmental biology, developmental proc ...

s depend on heritable changes to gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. T ...

that do not involve changes to the DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. T ...

. These changes can cross generations in plants, animals, and prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

s. This is not identical to traditional Lamarckism, as the changes do not last indefinitely and do not affect the germ line and hence the evolution of genes.

Catastrophism

Catastrophism is thehypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

, argued by the French anatomist and paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

in his 1812 ''Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes'', that the various extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the Endling, last individual of the species, although the Functional ext ...

s and the patterns of faunal succession seen in the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

record were caused by large-scale natural catastrophes such as volcanic eruptions and, for the most recent extinctions in Eurasia, the inundation of low-lying areas by the sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

. This was explained purely by natural events: he did not mention Noah's flood, nor did he ever refer to divine creation as the mechanism for repopulation after an extinction event, though he did not support evolutionary theories such as those of his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire either. Cuvier believed that the stratigraphic record indicated that there had been several such catastrophes, recurring natural events, separated by long periods of stability during the history of life on earth. This led him to believe the Earth was several million years old.

Catastrophism has found a place in modern biology with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period, as proposed in a paper by

Walter and Luis Alvarez in 1980. It argued that a asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere. ...

struck Earth 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period. The event, whatever it was, made about 70% of all species extinct, including the dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s, leaving behind the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary, formerly known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) boundary, is a geological signature, usually a thin band of rock containing much more iridium than other bands. The K–Pg boundary marks the end ...

. In 1990, a candidate crater marking the impact was identified at Chicxulub in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

.

Structuralism

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of body plans. Before Darwin,

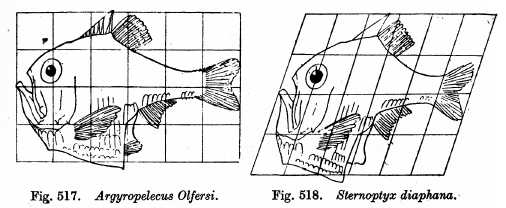

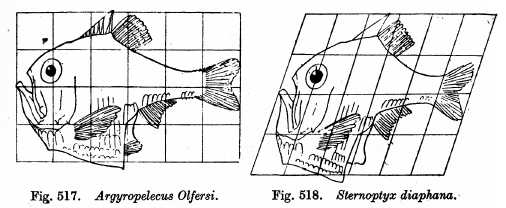

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of body plans. Before Darwin, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

argued that animals shared homologous parts, and that if one was enlarged, the others would be reduced in compensation. After Darwin, D'Arcy Thompson hinted at vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

and offered geometric explanations in his classic 1917 book '' On Growth and Form''. Adolf Seilacher suggested mechanical inflation for "pneu" structures in Ediacaran biota

The Ediacaran (; formerly Vendian) biota is a taxonomic period classification that consists of all life forms that were present on Earth during the Ediacaran Period (). These were composed of enigmatic tubular and frond-shaped, mostly sess ...

fossils such as ''Dickinsonia

''Dickinsonia'' is an extinct genus of basal animal that lived during the late Ediacaran period in what is now Australia, China, Russia and Ukraine. The individual ''Dickinsonia'' typically resembles a bilaterally symmetrical ribbed oval. Its a ...

''. Günter P. Wagner argued for developmental bias, structural constraints on embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

. Wagner, Günter P., ''Homology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation''. Princeton University Press. 2014. Chapter 1: The Intellectual Challenge of Morphological Evolution: A Case for Variational Structuralism. Pages 7–38 Stuart Kauffman favoured self-organisation

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spontaneous when suffic ...

, the idea that complex structure emerges holistically

Holism () is the idea that various systems (e.g. physical, biological, social) should be viewed as wholes, not merely as a collection of parts. The term "holism" was coined by Jan Smuts in his 1926 book ''Holism and Evolution''."holism, n." OED Onl ...

and spontaneously from the dynamic interaction of all parts of an organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fu ...

. Michael Denton argued for laws of form by which Platonic universals or "Types" are self-organised. In 1979 Stephen J. Gould

Stephen Jay Gould (; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould sp ...

and Richard Lewontin proposed biological "spandrels", features created as a byproduct of the adaptation of nearby structures. Gerd Müller

Gerhard "Gerd" Müller (; 3 November 1945 – 15 August 2021) was a German professional footballer. A striker renowned for his clinical finishing, especially in and around the six-yard box, he is widely regarded as one of the greatest goalscor ...

and Stuart Newman

Stuart Alan Newman (born April 4, 1945 in New York City) is a professor of cell biology and anatomy at New York Medical College in Valhalla, NY, United States. His research centers around three program areas: cellular and molecular mechanisms o ...

argued that the appearance in the fossil record of most of the current phyla Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

in the Cambrian explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil record. ...

was "pre- Mendelian" evolution caused by plastic responses of morphogenetic systems that were partly organized by physical mechanisms. Brian Goodwin

Brian Carey Goodwin (25 March 1931 – 15 July 2009) (St Anne de Bellevue, Quebec, Canada - Torbay, Devon, UK) was a Canadian mathematician and biologist, a Professor Emeritus at the Open University and a founder of theoretical biology and ...

, described by Wagner as part of "a fringe movement in evolutionary biology", denied that biological complexity can be reduced to natural selection, and argued that pattern formation

The science of pattern formation deals with the visible, ( statistically) orderly outcomes of self-organization and the common principles behind similar patterns in nature.

In developmental biology, pattern formation refers to the generation of ...

is driven by morphogenetic fields. Darwinian biologists have criticised structuralism, emphasising that there is plentiful evidence from deep homology

In evolutionary developmental biology, the concept of deep homology is used to describe cases where growth and differentiation processes are governed by genetic mechanisms that are homologous and deeply conserved across a wide range of specie ...

that gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s have been involved in shaping organisms throughout evolutionary history. They accept that some structures such as the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

self-assemble, but question the ability of self-organisation to drive large-scale evolution.

Saltationism, mutationism

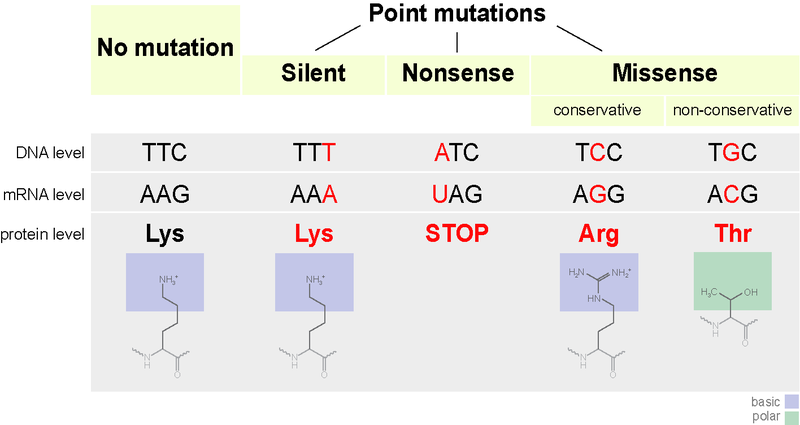

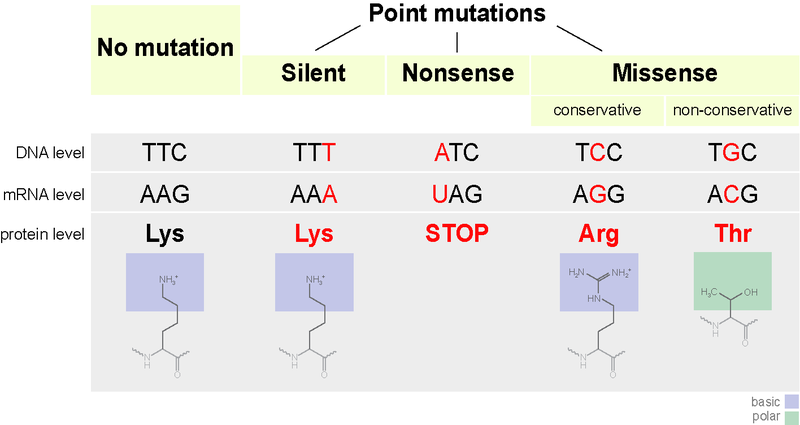

Saltationism held that new species arise as a result of largemutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, m ...

s. It was seen as a much faster alternative to the Darwinian concept of a gradual process of small random variations being acted on by natural selection. It was popular with early geneticists such as Hugo de Vries, who along with Carl Correns helped rediscover Gregor Mendel's laws of inheritance in 1900, William Bateson, a British zoologist who switched to genetics, and early in his career, Thomas Hunt Morgan. These ideas developed into mutationism, the mutation theory of evolution. This held that species went through periods of rapid mutation, possibly as a result of environmental stress, that could produce multiple mutations, and in some cases completely new species, in a single generation, based on de Vries's experiments with the evening primrose, '' Oenothera'', from 1886. The primroses seemed to be constantly producing new varieties with striking variations in form and color, some of which appeared to be new species because plants of the new generation could only be crossed with one another, not with their parents. However, Hermann Joseph Muller

Hermann Joseph Muller (December 21, 1890 – April 5, 1967) was an American geneticist, educator, and Nobel laureate best known for his work on the physiological and genetic effects of radiation ( mutagenesis), as well as his outspoken politica ...

showed in 1918 that the new varieties de Vries had observed were the result of polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set conta ...

hybrids rather than rapid genetic mutation.

Initially, de Vries and Morgan believed that mutations were so large as to create new forms such as subspecies or even species instantly. Morgan's 1910 fruit fly experiments, in which he isolated mutations for characteristics such as white eyes, changed his mind. He saw that mutations represented small Mendelian characteristics that would only spread through a population when they were beneficial, helped by natural selection. This represented the germ of the modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and ...

, and the beginning of the end for mutationism as an evolutionary force.

Contemporary biologists accept that mutation and selection both play roles in evolution; the mainstream view is that while mutation supplies material for selection in the form of variation, all non-random outcomes are caused by natural selection. Masatoshi Nei argues instead that the production of more efficient genotypes by mutation is fundamental for evolution, and that evolution is often mutation-limited. The endosymbiotic theory

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory,) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possib ...

implies rare but major events of saltational evolution by symbiogenesis. Carl Woese and colleagues suggested that the absence of RNA signature continuum between domains of bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeba ...

, and eukarya shows that these major lineages materialized via large saltations in cellular organization. Saltation at a variety of scales is agreed to be possible by mechanisms including polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set conta ...

y, which certainly can create new species of plant, gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. ...

, lateral gene transfer, and transposable element

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transp ...

s (jumping genes).

Genetic drift

The neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura in 1968, holds that at the molecular level most

The neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura in 1968, holds that at the molecular level most evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary changes and most of the variation within and between species is not caused by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

but by genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

of mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It ...

allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chrom ...

s that are neutral. A neutral mutation is one that does not affect an organism's ability to survive and reproduce. The neutral theory allows for the possibility that most mutations are deleterious, but holds that because these are rapidly purged by natural selection, they do not make significant contributions to variation within and between species at the molecular level. Mutations that are not deleterious are assumed to be mostly neutral rather than beneficial.

The theory was controversial as it sounded like a challenge to Darwinian evolution; controversy was intensified by a 1969 paper by Jack Lester King and Thomas H. Jukes

Thomas Hughes Jukes (August 26, 1906 – November 1, 1999) was a British-born American biologist known for his work in nutrition, molecular evolution, and for his public engagement with controversial scientific issues, including DDT, vitam ...

, provocatively but misleadingly titled "Non-Darwinian Evolution

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of evolution and the relatedness of different groups of living things. The alternatives in question do not deny that evolutionary changes ove ...

". It provided a wide variety of evidence including protein sequence

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosyn ...

comparisons, studies of the Treffers mutator gene in '' E. coli'', analysis of the genetic code, and comparative immunology

Immunology is a branch of medicineImmunology for Medical Students, Roderick Nairn, Matthew Helbert, Mosby, 2007 and biology that covers the medical study of immune systems in humans, animals, plants and sapient species. In such we can see ther ...

, to argue that most protein evolution is due to neutral mutations and genetic drift.

According to Kimura, the theory applies only for evolution at the molecular level, while phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological pr ...

evolution is controlled by natural selection, so the neutral theory does not constitute a true alternative.

Combined theories

Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interes ...

is a case in point. Cope, a religious man, began his career denying the possibility of evolution. In the 1860s, he accepted that evolution could occur, but, influenced by Agassiz, rejected natural selection. Cope accepted instead the theory of recapitulation of evolutionary history during the growth of the embryo - that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

, which Agassiz believed showed a divine plan leading straight up to man, in a pattern revealed both in embryology

Embryology (from Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, '' -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the prenatal development of gametes (sex cells), fertilization, and development of embr ...

and palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

. Cope did not go so far, seeing that evolution created a branching tree of forms, as Darwin had suggested. Each evolutionary step was however non-random: the direction was determined in advance and had a regular pattern (orthogenesis), and steps were not adaptive but part of a divine plan (theistic evolution). This left unanswered the question of why each step should occur, and Cope switched his theory to accommodate functional adaptation for each change. Still rejecting natural selection as the cause of adaptation, Cope turned to Lamarckism to provide the force guiding evolution. Finally, Cope supposed that Lamarckian use and disuse operated by causing a vitalist growth-force substance, "bathmism", to be concentrated in the areas of the body being most intensively used; in turn, it made these areas develop at the expense of the rest. Cope's complex set of beliefs thus assembled five evolutionary philosophies: recapitulationism, orthogenesis, theistic evolution, Lamarckism, and vitalism. Other palaeontologists and field naturalists continued to hold beliefs combining orthogenesis and Lamarckism until the modern synthesis in the 1930s.

Rebirth of natural selection, with continuing alternatives

By the start of the 20th century, during the eclipse of Darwinism, biologists were doubtful of natural selection, but equally were quick to discount theories such as orthogenesis, vitalism and Lamarckism which offered no mechanism for evolution. Mutationism did propose a mechanism, but it was not generally accepted. Themodern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and ...

a generation later, roughly between 1918 and 1932, broadly swept away all the alternatives to Darwinism, though some including forms of orthogenesis, epigenetic mechanisms that resemble Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics, catastrophism, structuralism, and mutationism have been revived, such as through the discovery of molecular mechanisms.

Biology has become Darwinian, but belief in some form of progress (orthogenesis) remains both in the public mind and among biologists. Ruse argues that evolutionary biologists will probably continue to believe in progress for three reasons. Firstly, the anthropic principle

The anthropic principle, also known as the "observation selection effect", is the hypothesis, first proposed in 1957 by Robert Dicke, that there is a restrictive lower bound on how statistically probable our observations of the universe are, bec ...

demands people able to ask about the process that led to their own existence, as if they were the pinnacle of such progress. Secondly, scientists in general and evolutionists in particular believe that their work is leading them progressively closer to a true grasp of reality, as knowledge increases, and hence (runs the argument) there is progress in nature also. Ruse notes in this regard that Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biologist and author. He is an emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford and was Professor for Public Understanding of Science in the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008. An ...

explicitly compares cultural progress with meme

A meme ( ) is an idea, behavior, or style that spreads by means of imitation from person to person within a culture and often carries symbolic meaning representing a particular phenomenon or theme. A meme acts as a unit for carrying cultural ...

s to biological progress with genes. Thirdly, evolutionists are self-selected; they are people, such as the entomologist and sociobiologist E. O. Wilson, who are interested in progress to supply a meaning for life.

See also

*Coloration evidence for natural selection

Animal coloration provided important early evidence for evolution by natural selection, at a time when little direct evidence was available. Three major functions of coloration were discovered in the second half of the 19th century, and subs ...

* History of evolutionary thought

* Objections to evolution

Objections to evolution have been raised since evolutionary ideas came to prominence in the 19th century. When Charles Darwin published his 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species'', his theory of evolution (the idea that species arose through desc ...

* Extended evolutionary synthesis

The extended evolutionary synthesis consists of a set of theoretical concepts argued to be more comprehensive than the earlier modern synthesis of evolutionary biology that took place between 1918 and 1942. The extended evolutionary synthesis w ...

* Lysenkoism

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Evolution Evolutionary biology History of evolutionary biology Non-Darwinian evolution