Almagest on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the  Ptolemy set up a public inscription at

Ptolemy set up a public inscription at

The layout of the catalogue has always been tabular (

The layout of the catalogue has always been tabular (

Latin translationa Greek MS

. Ptolemy writes explicitly that the coordinates are given as (ecliptical) "longitudes" and "latitudes", which are given in columns, so this has probably always been the case. It is significant that Ptolemy chooses the ecliptical coordinate system because of his knowledge of precession, which distinguishes him from all his predecessors. Hipparchus' celestial globe had an ecliptic drawn in, but the coordinates were equatorial. Since Hipparchus' star catalogue has not survived in its original form, but was absorbed into the Almagest star catalogue (and heavily revised in the 265 years in between), the Almagest star catalogue is the oldest one in which complete tables of coordinates and magnitudes have come down to us. As mentioned, Ptolemy includes a star catalog containing 1022 stars. He says that he "observed as many stars as it was possible to perceive, even to the sixth magnitude", and that the ecliptic longitudes are for the beginning of the reign of Antoninus Pius (138 AD). Ptolemy himself states that he found that the longitudes had increased by 2° 40′ since the time of Subtracting the systematic error leaves other errors that cannot be explained by precession. Of these errors, about 18 to 20 are also found in Hipparchus' star catalogue (which can only be reconstructed incompletely). From this it can be concluded that a subset of star coordinates in the Almagest can indeed be traced back to Hipparchus, but not that the complete star catalogue was simply "copied". Rather, Hipparchus' major errors are no longer present in the Almagest and, on the other hand, Hipparchus' star catalogue had some stars that are entirely absent from the Almagest. It can be concluded that Hipparchus' star catalogue, while forming the basis, has been reobserved and revised.

Subtracting the systematic error leaves other errors that cannot be explained by precession. Of these errors, about 18 to 20 are also found in Hipparchus' star catalogue (which can only be reconstructed incompletely). From this it can be concluded that a subset of star coordinates in the Almagest can indeed be traced back to Hipparchus, but not that the complete star catalogue was simply "copied". Rather, Hipparchus' major errors are no longer present in the Almagest and, on the other hand, Hipparchus' star catalogue had some stars that are entirely absent from the Almagest. It can be concluded that Hipparchus' star catalogue, while forming the basis, has been reobserved and revised.

Stellarium

since 2019. These constellations form the basis for the modern

Ptolemy assigned the following order to the planetary spheres, beginning with the innermost:

# Moon

# Mercury

# Venus

# Sun

# Mars

# Jupiter

# Saturn

# Sphere of fixed stars

Other classical writers suggested different sequences.

Ptolemy assigned the following order to the planetary spheres, beginning with the innermost:

# Moon

# Mercury

# Venus

# Sun

# Mars

# Jupiter

# Saturn

# Sphere of fixed stars

Other classical writers suggested different sequences.

The first translations into Arabic were made in the 9th century, with two separate efforts, one sponsored by the

The first translations into Arabic were made in the 9th century, with two separate efforts, one sponsored by the  In the 15th century, a Greek version appeared in Western Europe. The German astronomer Johannes Müller (known, from his birthplace of

In the 15th century, a Greek version appeared in Western Europe. The German astronomer Johannes Müller (known, from his birthplace of

Ptolemy's cataloque of stars.djvu, page=9, Ptolemy's catalogue of stars; a revision of the ''Almagest'' by Christian Heinrich Friedrich Peters and Edward Ball Knobel, 1915

File:Epytoma Ioannis de Monte Regio in Almagestum Ptolomei.djvu, page=9, Epytoma Ioannis de Monte Regio in ''Almagestum'' Ptolomei, Latin, 1496

File:Claudius Ptolemaeus, Almagestum, 1515.djvu, page=2, ''Almagestum'', Latin, 1515

Syntaxis mathematica in J.L. Heiberg's edition (1898–1903)

Ptolemy's ''De Analemmate''. PDF scans of Heiberg's Greek edition, now in the public domain

(Koine Greek)

Toomer's English translation

Duckworth, 1984.

Ptolemy. ''Almagest''.

Latin translation from the Arabic by Gerard of Cremona. Digitized version of manuscript made in Northern Italy c. 1200–1225 held by the State Library of Victoria.

University of Vienna: ''Almagestum'' (1515)

PDFs of different resolutions. Edition of Petrus Liechtenstein, Latin translation of Gerard of Cremona.

Online luni-solar and planetary ephemeris calculator based on the ''Almagest''

A podcast discussion by Prof. M Heath and Dr A. Chapman of a recent re-discovery of a 14th-century manuscript in the university of Leeds Library

in

Animation of Ptolemy's model of the universe

by Andre Rehak (YouTube) * (Hebrew

Maimonides explaining why you need to learn Almagest first to understand science

{{Authority control Ancient Greek astronomical works Astronomy books Works by Ptolemy 2nd-century books

star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s and planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

ary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importa ...

( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canonized a geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

of the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

that was accepted for more than 1,200 years from its origin in Hellenistic Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, in the medieval Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ma ...

worlds, and in Western Europe through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

and early Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

until Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

. It is also a key source of information about ancient Greek astronomy

Greek astronomy is astronomy written in the Greek language in classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and Late Antiquity eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to ...

.

Ptolemy set up a public inscription at

Ptolemy set up a public inscription at Canopus, Egypt

Canopus (, ; grc-gre, Κάνωπος, ), also known as Canobus ( grc-gre, Κάνωβος, ), was an ancient Egyptian coastal town, located in the Nile Delta. Its site is in the eastern outskirts of modern-day Alexandria, around from the cent ...

, in 147 or 148. N. T. Hamilton found that the version of Ptolemy's models set out in the ''Canopic Inscription'' was earlier than the version in the ''Almagest''. Hence the ''Almagest'' could not have been completed before about 150, a quarter-century after Ptolemy began observing.

Names

The name comes from Arabic ', with ' meaning "the", and ''magesti'' being a corruption of Greek ' 'greatest'. The work was originally titled "" (') inAncient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

, and also called ''Syntaxis Mathematica'' in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

. The treatise was later titled ' (, "The Great Treatise"; la, Magna Syntaxis), and the superlative form of this ( grc, μεγίστη, ''megiste'', "greatest") lies behind the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

name ' (), from which the English name ''Almagest'' derives. The Arabic name is important due to the popularity of a Latin translation known as ''Almagestum'' made in the 12th century from an Arabic translation, which would endure until original Greek copies resurfaced in the 15th century.

Contents

Books

The ''Syntaxis Mathematica'' consists of thirteen sections, called books. As with many medieval manuscripts that were handcopied or, particularly, printed in the early years of printing, there were considerable differences between various editions of the same text, as the process of transcription was highly personal. An example illustrating how the ''Syntaxis'' was organized is given below. It is a Latin edition printed in 1515 at Venice by Petrus Lichtenstein. * Book I contains an outline ofAristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

's cosmology: on the spherical form of the heavens, with the spherical Earth lying motionless as the center, with the fixed stars

In astronomy, fixed stars ( la, stellae fixae) is a term to name the full set of glowing points, astronomical objects actually and mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the backgro ...

and the various planets revolving around the Earth. Then follows an explanation of chords with table of chords; observations of the obliquity of the ecliptic (the apparent path of the Sun through the stars); and an introduction to spherical trigonometry.

* Book II covers problems associated with the daily motion attributed to the heavens, namely risings and settings of celestial objects, the length of daylight, the determination of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

, the points at which the Sun is vertical, the shadows of the gnomon

A gnomon (; ) is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the ...

at the equinoxes and solstice

A solstice is an event that occurs when the Sun appears to reach its most northerly or southerly excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around June 21 and December 21. In many count ...

s, and other observations that change with the observer's position. There is also a study of the angles made by the ecliptic with the vertical, with tables.

* Book III covers the length of the year, and the motion of the Sun. Ptolemy explains Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the e ...

' discovery of the precession of the equinoxes and begins explaining the theory of epicycles.

* Books IV and V cover the motion of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, lunar parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby object ...

, the motion of the lunar apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any el ...

, and the sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon relative to the Earth.

* Book VI covers solar and lunar eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three c ...

s.

* Books VII and VIII cover the motions of the fixed stars, including precession of the equinoxes. They also contain a star catalogue of 1022 stars, described by their positions in the constellation

A constellation is an area on the celestial sphere in which a group of visible stars forms a perceived pattern or outline, typically representing an animal, mythological subject, or inanimate object.

The origins of the earliest constellation ...

s, together with ecliptic longitude and latitude. (The catalogue actually contained 1,028 entries, but three of these were deliberate duplicates, because Ptolemy regarded certain stars as being shared between adjacent constellations. Three other entries were non-stellar, i.e. the Double Cluster in Perseus, M44 (Praesepe) in Cancer, and the globular cluster Omega Centauri.)

Ptolemy states that the longitudes (which increase due to precession) are for the beginning of the reign of Antoninus Pius (138 AD), whereas the latitudes do not change with time. (But see below, under The star catalog.) The constellations north of the zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The pa ...

and the northern zodiac constellations (Aries through Virgo) are in the table at the end of Book VII, while the rest are in the table at the beginning of Book VIII. The brightest stars were marked first magnitude (''m'' = 1), while the faintest visible to the naked eye were sixth magnitude (''m'' = 6). Each numerical magnitude was considered twice the brightness of the following one, which is a logarithmic scale. (The ratio was subjective as no photodetectors existed.) This system is believed to have originated with Hipparchus. The stellar positions too are of Hipparchan origin, despite Ptolemy's claim to the contrary.

: Ptolemy identified 48 constellations: The 12 of the zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The pa ...

, 21 to the north of the zodiac, and 15 to the south.

* Book IX addresses general issues associated with creating models for the five naked eye planets, and the motion of Mercury.

* Book X covers the motions of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

and Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

.

* Book XI covers the motions of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

.

* Book XII covers stations and retrograde motion

Retrograde motion in astronomy is, in general, orbital or rotational motion of an object in the direction opposite the rotation of its primary, that is, the central object (right figure). It may also describe other motions such as precession ...

, which occurs when planets appear to pause, then briefly reverse their motion against the background of the zodiac. Ptolemy understood these terms to apply to Mercury and Venus as well as the outer planets.

* Book XIII covers motion in latitude, that is, the deviation of planets from the ecliptic.

Ptolemy's cosmos

The cosmology of the ''Syntaxis'' includes five main points, each of which is the subject of a chapter in Book I. What follows is a close paraphrase of Ptolemy's own words from Toomer's translation. * The celestial realm is spherical, and moves as a sphere. * The Earth is a sphere. * The Earth is at the center of the cosmos. * The Earth, in relation to the distance of the fixed stars, has no appreciable size and must be treated as a mathematical point. * The Earth does not move.The star catalog

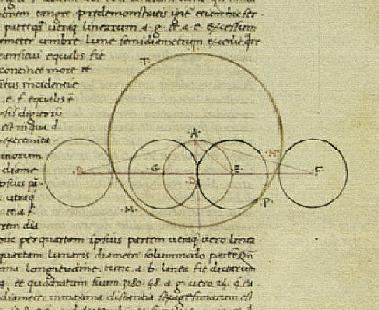

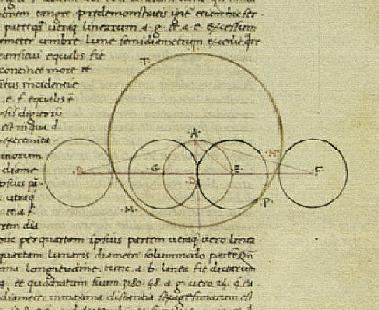

The layout of the catalogue has always been tabular (

The layout of the catalogue has always been tabular (Latin translation

. Ptolemy writes explicitly that the coordinates are given as (ecliptical) "longitudes" and "latitudes", which are given in columns, so this has probably always been the case. It is significant that Ptolemy chooses the ecliptical coordinate system because of his knowledge of precession, which distinguishes him from all his predecessors. Hipparchus' celestial globe had an ecliptic drawn in, but the coordinates were equatorial. Since Hipparchus' star catalogue has not survived in its original form, but was absorbed into the Almagest star catalogue (and heavily revised in the 265 years in between), the Almagest star catalogue is the oldest one in which complete tables of coordinates and magnitudes have come down to us. As mentioned, Ptolemy includes a star catalog containing 1022 stars. He says that he "observed as many stars as it was possible to perceive, even to the sixth magnitude", and that the ecliptic longitudes are for the beginning of the reign of Antoninus Pius (138 AD). Ptolemy himself states that he found that the longitudes had increased by 2° 40′ since the time of

Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the e ...

which was 265 years earlier (Alm. VII, 2). But calculations show that his ecliptic longitudes correspond more closely to around the middle of the first century CE (+48 to +58).

Since Tycho Brahe found this offset, astronomers and historians investigated this problem and suggested several causes:

* that all coordinates were calculated from Hipparchus' observations, whereby the precession constant, which was known too inaccurately at the time, led to a summation error (Delambre 1817).

* that the data had in fact been observed a century earlier by Menelaus of Alexandria (Björnbo 1901)

* that the difference is a sum of individual errors of various kinds, including calibration with outdated solar data (Dreyer 1917)

* that Ptolemy's instrument was wrongly calibrated and had a systematic offset (Vogt 1925).

Subtracting the systematic error leaves other errors that cannot be explained by precession. Of these errors, about 18 to 20 are also found in Hipparchus' star catalogue (which can only be reconstructed incompletely). From this it can be concluded that a subset of star coordinates in the Almagest can indeed be traced back to Hipparchus, but not that the complete star catalogue was simply "copied". Rather, Hipparchus' major errors are no longer present in the Almagest and, on the other hand, Hipparchus' star catalogue had some stars that are entirely absent from the Almagest. It can be concluded that Hipparchus' star catalogue, while forming the basis, has been reobserved and revised.

Subtracting the systematic error leaves other errors that cannot be explained by precession. Of these errors, about 18 to 20 are also found in Hipparchus' star catalogue (which can only be reconstructed incompletely). From this it can be concluded that a subset of star coordinates in the Almagest can indeed be traced back to Hipparchus, but not that the complete star catalogue was simply "copied". Rather, Hipparchus' major errors are no longer present in the Almagest and, on the other hand, Hipparchus' star catalogue had some stars that are entirely absent from the Almagest. It can be concluded that Hipparchus' star catalogue, while forming the basis, has been reobserved and revised.

Errors in the coordinates

The figure he used is based on Hipparchus' own estimate for precession, which was 1° in 100 years, instead of the correct 1° in 72 years. Dating attempts through proper motion of the stars also appear to date the actual observation to Hipparchus' time instead of Ptolemy. Many of the longitudes and latitudes have been corrupted in the various manuscripts. Most of these errors can be explained by similarities in the symbols used for different numbers. For example, the Greek letters Α and Δ were used to mean 1 and 4 respectively, but because these look similar copyists sometimes wrote the wrong one. In Arabic manuscripts, there was confusion between for example 3 and 8 (ج and ح). (At least one translator also introduced errors. Gerard of Cremona, who translated an Arabic manuscript into Latin around 1175, put 300° for the latitude of several stars. He had apparently learned fromMoors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinc ...

, who used the letter "sin" for 300 (like the Hebrew " shin"), but the manuscript he was translating came from the East, where "sin" was used for 60, like the Hebrew " samech".)

Even without the errors introduced by copyists, and even accounting for the fact that the longitudes are more appropriate for 58 AD than for 137 AD, the latitudes and longitudes are not fully accurate, with errors as great as large fractions of a degree. Some errors may be due to atmospheric refraction causing stars that are low in the sky to appear higher than where they really are. A series of stars in Centaurus are off by a couple degrees, including the star we call Alpha Centauri

Alpha Centauri ( Latinized from α Centauri and often abbreviated Alpha Cen or α Cen) is a triple star system in the constellation of Centaurus. It consists of 3 stars: Alpha Centauri A (officially Rigil Kentaurus), Alpha Centa ...

. These were probably measured by a different person or persons from the others, and in an inaccurate way.

Constellations in the star catalogue

The star catalogue contains 48 constellations, which have different surface areas and numbers of stars. In Book VIII, Chapter 3, Ptolemy writes that the constellations should be outlined on a globe, but it is unclear exactly how he means this: should surrounding polygons be drawn or should the figures be sketched or even line figures be drawn? This is not stated. Although no line figures have survived from antiquity, the figures can be reconstructed on the basis of the descriptions in the star catalogue: The exact celestial coordinates of the figures' heads, feet, arms, wings and other body parts are recorded. It is therefore possible to draw the stick figures in the modern sense so that they fit the description in the Almagest. These modern stick figures as a reconstruction of the historical constellations of the Almagest are available in the free planetarium softwarStellarium

since 2019. These constellations form the basis for the modern

constellation

A constellation is an area on the celestial sphere in which a group of visible stars forms a perceived pattern or outline, typically representing an animal, mythological subject, or inanimate object.

The origins of the earliest constellation ...

s that were formally adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, with official boundaries that were agreed in 1928.

Of the stars in the catalogue, 108 (just over 10%) were classified by Ptolemy as ‘unformed’, by which he meant lying outside the recognized constellation figures. These were later absorbed into their surrounding constellations or in some cases used to form new constellations.

Ptolemy's planetary model

Ptolemy assigned the following order to the planetary spheres, beginning with the innermost:

# Moon

# Mercury

# Venus

# Sun

# Mars

# Jupiter

# Saturn

# Sphere of fixed stars

Other classical writers suggested different sequences.

Ptolemy assigned the following order to the planetary spheres, beginning with the innermost:

# Moon

# Mercury

# Venus

# Sun

# Mars

# Jupiter

# Saturn

# Sphere of fixed stars

Other classical writers suggested different sequences. Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(c. 427 – c. 347 BC) placed the Sun second in order after the Moon. Martianus Capella (5th century AD) put Mercury and Venus in motion around the Sun. Ptolemy's authority was preferred by most medieval Islamic and late medieval European astronomers.

Ptolemy inherited from his Greek predecessors a geometrical toolbox and a partial set of models for predicting where the planets would appear in the sky. Apollonius of Perga

Apollonius of Perga ( grc-gre, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Περγαῖος, Apollṓnios ho Pergaîos; la, Apollonius Pergaeus; ) was an Ancient Greek geometer and astronomer known for his work on conic sections. Beginning from the contributio ...

(c. 262 – c. 190 BC) had introduced the deferent and epicycle and the eccentric deferent to astronomy. Hipparchus (2nd century BC) had crafted mathematical models of the motion of the Sun and Moon. Hipparchus had some knowledge of Mesopotamian astronomy, and he felt that Greek models should match those of the Babylonians in accuracy. He was unable to create accurate models for the remaining five planets.

The ''Syntaxis'' adopted Hipparchus' solar model, which consisted of a simple eccentric deferent. For the Moon, Ptolemy began with Hipparchus' epicycle-on-deferent, then added a device that historians of astronomy refer to as a "crank mechanism": He succeeded in creating models for the other planets, where Hipparchus had failed, by introducing a third device called the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

.

Ptolemy wrote the ''Syntaxis'' as a textbook of mathematical astronomy. It explained geometrical models of the planets based on combinations of circles, which could be used to predict the motions of celestial objects. In a later book, the ''Planetary Hypotheses'', Ptolemy explained how to transform his geometrical models into three-dimensional spheres or partial spheres. In contrast to the mathematical ''Syntaxis'', the ''Planetary Hypotheses'' is sometimes described as a book of cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

.

Impact

Ptolemy's comprehensive treatise of mathematical astronomy superseded most older texts of Greek astronomy. Some were more specialized and thus of less interest; others simply became outdated by the newer models. As a result, the older texts ceased to be copied and were gradually lost. Much of what we know about the work of astronomers like Hipparchus comes from references in the ''Syntaxis''. The first translations into Arabic were made in the 9th century, with two separate efforts, one sponsored by the

The first translations into Arabic were made in the 9th century, with two separate efforts, one sponsored by the caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Al-Ma'mun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'm ...

, who received a copy as a condition of peace with the Byzantine emperor. Sahl ibn Bishr is thought to be the first Arabic translator.

No Latin translation was made in the Ancient Rome nor the Medieval West before the 12th century. Henry Aristippus made the first Latin translation directly from a Greek copy, but it was not as influential as a later translation into Latin made in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

by Gerard of Cremona from the Arabic (finished in 1175). Gerard translated the Arabic text while working at the Toledo School of Translators

The Toledo School of Translators ( es, Escuela de Traductores de Toledo) is the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the Judeo-Islamic philosophies and scientific w ...

, although he was unable to translate many technical terms such as the Arabic ''Abrachir'' for Hipparchus. In the 13th century a Spanish version was produced, which was later translated under the patronage of Alfonso X

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Ger ...

.

In the 15th century, a Greek version appeared in Western Europe. The German astronomer Johannes Müller (known, from his birthplace of

In the 15th century, a Greek version appeared in Western Europe. The German astronomer Johannes Müller (known, from his birthplace of Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

, as Regiomontanus) made an abridged Latin version at the instigation of the Greek churchman Cardinal Bessarion. Around the same time, George of Trebizond made a full translation accompanied by a commentary that was as long as the original text. George's translation, done under the patronage of Pope Nicholas V, was intended to supplant the old translation. The new translation was a great improvement; the new commentary was not, and aroused criticism. The Pope declined the dedication of George's work, and Regiomontanus's translation had the upper hand for over 100 years.

During the 16th century, Guillaume Postel, who had been on an embassy to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, brought back Arabic disputations of the ''Almagest'', such as the works of al-Kharaqī, ''Muntahā al-idrāk fī taqāsīm al-aflāk'' ("The Ultimate Grasp of the Divisions of Spheres", 1138/9).

Commentaries on the ''Syntaxis'' were written by Theon of Alexandria

Theon of Alexandria (; grc, Θέων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; 335 – c. 405) was a Greek scholar and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. He edited and arranged Euclid's '' Elements'' and wrote commentaries on w ...

(extant), Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Πάππος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; AD) was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem i ...

(only fragments survive), and Ammonius Hermiae (lost).

Modern editions

The ''Almagest'' under the Latin title ''Syntaxis mathematica'', was edited by J. L. Heiberg in ''Claudii Ptolemaei opera quae exstant omnia'', vols. 1.1 and 1.2 (1898, 1903). Three translations of the ''Almagest'' into English have been published. The first, byR. Catesby Taliaferro

Robert Catesby Taliaferro (1907–1989) was an American mathematician, science historian, classical philologist, philosopher, and translator of ancient Greek and Latin works into English. An Episcopalian from an old Virginia family, he taught in ...

of St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, was included in volume 16 of the '' Great Books of the Western World'' in 1952. The second, by G. J. Toomer

Gerald James Toomer (born 23 November 1934) is a historian of astronomy and mathematics who has written numerous books and papers on ancient Greek and medieval Islamic astronomy. In particular, he translated Ptolemy's ''Almagest'' into English ...

, ''Ptolemy's Almagest'' in 1984, with a second edition in 1998. The third was a partial translation by Bruce M. Perry in ''The Almagest: Introduction to the Mathematics of the Heavens'' in 2014.

A direct French translation from the Greek text was published in two volumes in 1813 and 1816 by Nicholas Halma, including detailed historical comments in a 69-page preface. It has been described as "suffer ngfrom excessive literalness, particularly where the text is difficult" by Toomer, and as "very faulty" by Serge Jodra. The scanned books are available in full at the '' Gallica'' French national library.

Gallery

See also

* Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī (who also wrote an ''Almagest'') * '' Book of Fixed Stars'' *Star cartography

Celestial cartography, uranography,

astrography or star cartography is the aspect of astronomy and branch of cartography concerned with mapping stars, galaxies, and other astronomical objects on the celestial sphere. Measuring the position ...

Footnotes

References

* James Evans (1998) ''The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy'',Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

.

* Michael Hoskin (1999) ''The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy'', Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

.

* Olaf Pedersen

Olaf Pedersen (8 April 1920 – 3 December 1997) was a Danish historian of science who was "leading authority on astronomy in classical antiquity and the Latin middle ages."Michael Hoskin (October 1998Obituary: Olaf PedersenAstronomy and Geophys ...

(1974) ''A Survey of the Almagest'', Odense University Press .

* Alexander Jones & Olaf Pedersen (2011) ''A Survey of the Almagest'', Springer .

* Olaf Pedersen (1993) ''Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction'', 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press

* Otto Neugebauer (1975) ''A History of ancient mathematical Astronomy'', Springer-Verlag

Springer Science+Business Media, commonly known as Springer, is a German multinational publishing company of books, e-books and peer-reviewed journals in science, humanities, technical and medical (STM) publishing.

Originally founded in 1842 ...

, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York .

External links

Syntaxis mathematica in J.L. Heiberg's edition (1898–1903)

Ptolemy's ''De Analemmate''. PDF scans of Heiberg's Greek edition, now in the public domain

(Koine Greek)

Toomer's English translation

Duckworth, 1984.

Ptolemy. ''Almagest''.

Latin translation from the Arabic by Gerard of Cremona. Digitized version of manuscript made in Northern Italy c. 1200–1225 held by the State Library of Victoria.

University of Vienna: ''Almagestum'' (1515)

PDFs of different resolutions. Edition of Petrus Liechtenstein, Latin translation of Gerard of Cremona.

Online luni-solar and planetary ephemeris calculator based on the ''Almagest''

A podcast discussion by Prof. M Heath and Dr A. Chapman of a recent re-discovery of a 14th-century manuscript in the university of Leeds Library

in

ASCII

ASCII ( ), abbreviated from American Standard Code for Information Interchange, is a character encoding standard for electronic communication. ASCII codes represent text in computers, telecommunications equipment, and other devices. Because ...

(Latin)

Animation of Ptolemy's model of the universe

by Andre Rehak (YouTube) * (Hebrew

Maimonides explaining why you need to learn Almagest first to understand science

{{Authority control Ancient Greek astronomical works Astronomy books Works by Ptolemy 2nd-century books