Allosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Allosaurus'' () is a

Although sporadic work at what became known as the

Although sporadic work at what became known as the

In 1991, "Big Al" ( MOR 693), a 95% complete, partially articulated specimen of ''Allosaurus'' was discovered. It measured about 8 meters (about 26 ft) in length. MOR 693 was excavated near Shell, Wyoming, by a joint Museum of the Rockies and University of Wyoming Geological Museum team. This skeleton was discovered by a Swiss team, led by Kirby Siber. Chure and Loewen in 2020 identified the individual as a representative of the species ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''. In 1996, the same team discovered a second ''Allosaurus'', "Big Al II". This specimen, the best preserved skeleton of its kind to date, is also referred to ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''.

The completeness, preservation, and scientific importance of this skeleton gave "Big Al" its name; the individual itself was below the average size for ''Allosaurus fragilis'', and was a subadult estimated at only 87% grown. The specimen was described by Breithaupt in 1996. Nineteen of its bones were broken or showed signs of

In 1991, "Big Al" ( MOR 693), a 95% complete, partially articulated specimen of ''Allosaurus'' was discovered. It measured about 8 meters (about 26 ft) in length. MOR 693 was excavated near Shell, Wyoming, by a joint Museum of the Rockies and University of Wyoming Geological Museum team. This skeleton was discovered by a Swiss team, led by Kirby Siber. Chure and Loewen in 2020 identified the individual as a representative of the species ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''. In 1996, the same team discovered a second ''Allosaurus'', "Big Al II". This specimen, the best preserved skeleton of its kind to date, is also referred to ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''.

The completeness, preservation, and scientific importance of this skeleton gave "Big Al" its name; the individual itself was below the average size for ''Allosaurus fragilis'', and was a subadult estimated at only 87% grown. The specimen was described by Breithaupt in 1996. Nineteen of its bones were broken or showed signs of

Six species of ''Allosaurus'' have been named: ''A. amplus'', ''A. atrox'', ''A. europaeus'', the

Six species of ''Allosaurus'' have been named: ''A. amplus'', ''A. atrox'', ''A. europaeus'', the

''Creosaurus'', ''Epanterias'', and ''Labrosaurus'' are regarded as junior synonyms of ''Allosaurus''. Most of the species that are regarded as synonyms of ''A. fragilis'', or that were misassigned to the genus, are obscure and were based on scrappy remains. One exception is ''Labrosaurus ferox'', named in 1884 by Marsh for an oddly formed partial lower jaw, with a prominent gap in the tooth row at the tip of the jaw, and a rear section greatly expanded and turned down. Later researchers suggested that the bone was

''Creosaurus'', ''Epanterias'', and ''Labrosaurus'' are regarded as junior synonyms of ''Allosaurus''. Most of the species that are regarded as synonyms of ''A. fragilis'', or that were misassigned to the genus, are obscure and were based on scrappy remains. One exception is ''Labrosaurus ferox'', named in 1884 by Marsh for an oddly formed partial lower jaw, with a prominent gap in the tooth row at the tip of the jaw, and a rear section greatly expanded and turned down. Later researchers suggested that the bone was

Several species initially classified within or referred to ''Allosaurus'' do not belong within the genus. ''A. medius'' was named by Marsh in 1888 for various specimens from the Early Cretaceous

Several species initially classified within or referred to ''Allosaurus'' do not belong within the genus. ''A. medius'' was named by Marsh in 1888 for various specimens from the Early Cretaceous  ''A. tendagurensis'' was named in 1925 by

''A. tendagurensis'' was named in 1925 by

''Allosaurus'' was a typical large

''Allosaurus'' was a typical large  Several gigantic specimens have been attributed to ''Allosaurus'', but may in fact belong to other genera. The closely related genus ''

Several gigantic specimens have been attributed to ''Allosaurus'', but may in fact belong to other genera. The closely related genus ''

The skull and teeth of ''Allosaurus'' were modestly proportioned for a theropod of its size. Paleontologist

The skull and teeth of ''Allosaurus'' were modestly proportioned for a theropod of its size. Paleontologist

''Allosaurus'' had nine

''Allosaurus'' had nine  The forelimbs of ''Allosaurus'' were short in comparison to the hindlimbs (only about 35% the length of the hindlimbs in adults) and had three fingers per hand, tipped with large, strongly curved and pointed

The forelimbs of ''Allosaurus'' were short in comparison to the hindlimbs (only about 35% the length of the hindlimbs in adults) and had three fingers per hand, tipped with large, strongly curved and pointed

Below is a cladogram based on the analysis of Benson ''et al.'' in 2010.

Allosauridae is one of four families in Allosauroidea; the other three are

Below is a cladogram based on the analysis of Benson ''et al.'' in 2010.

Allosauridae is one of four families in Allosauroidea; the other three are

The wealth of ''Allosaurus'' fossils, from nearly all ages of individuals, allows scientists to study how the animal grew and how long its lifespan may have been. Remains may reach as far back in the lifespan as

The wealth of ''Allosaurus'' fossils, from nearly all ages of individuals, allows scientists to study how the animal grew and how long its lifespan may have been. Remains may reach as far back in the lifespan as  The discovery of a juvenile specimen with a nearly complete hindlimb shows that the legs were relatively longer in juveniles, and the lower segments of the leg (shin and foot) were relatively longer than the thigh. These differences suggest that younger ''Allosaurus'' were faster and had different hunting strategies than adults, perhaps chasing small prey as juveniles, then becoming ambush hunters of large prey upon adulthood. The

The discovery of a juvenile specimen with a nearly complete hindlimb shows that the legs were relatively longer in juveniles, and the lower segments of the leg (shin and foot) were relatively longer than the thigh. These differences suggest that younger ''Allosaurus'' were faster and had different hunting strategies than adults, perhaps chasing small prey as juveniles, then becoming ambush hunters of large prey upon adulthood. The

Many paleontologists accept ''Allosaurus'' as an active predator of large animals. There is dramatic evidence for allosaur attacks on ''Stegosaurus'', including an ''Allosaurus'' tail vertebra with a partially healed puncture wound that fits a ''Stegosaurus'' tail spike, and a ''Stegosaurus'' neck plate with a U-shaped wound that correlates well with an ''Allosaurus'' snout. Sauropods seem to be likely candidates as both live prey and as objects of

Many paleontologists accept ''Allosaurus'' as an active predator of large animals. There is dramatic evidence for allosaur attacks on ''Stegosaurus'', including an ''Allosaurus'' tail vertebra with a partially healed puncture wound that fits a ''Stegosaurus'' tail spike, and a ''Stegosaurus'' neck plate with a U-shaped wound that correlates well with an ''Allosaurus'' snout. Sauropods seem to be likely candidates as both live prey and as objects of  Similar conclusions were drawn by another study using finite element analysis on an ''Allosaurus'' skull. According to their biomechanical analysis, the skull was very strong but had a relatively small bite force. By using jaw muscles only, it could produce a bite force of 805 to 8,724 N, but the skull could withstand nearly 55,500 N of vertical force against the tooth row. The authors suggested that ''Allosaurus'' used its skull like a machete against prey, attacking open-mouthed, slashing flesh with its teeth, and tearing it away without splintering bones, unlike ''Tyrannosaurus'', which is thought to have been capable of damaging bones. They also suggested that the architecture of the skull could have permitted the use of different strategies against different prey; the skull was light enough to allow attacks on smaller and more agile ornithopods, but strong enough for high-impact ambush attacks against larger prey like stegosaurids and sauropods. Their interpretations were challenged by other researchers, who found no modern analogues to a hatchet attack and considered it more likely that the skull was strong to compensate for its open construction when absorbing the stresses from struggling prey. The original authors noted that ''Allosaurus'' itself has no modern equivalent, that the tooth row is well-suited to such an attack, and that articulations in the skull cited by their detractors as problematic actually helped protect the

Similar conclusions were drawn by another study using finite element analysis on an ''Allosaurus'' skull. According to their biomechanical analysis, the skull was very strong but had a relatively small bite force. By using jaw muscles only, it could produce a bite force of 805 to 8,724 N, but the skull could withstand nearly 55,500 N of vertical force against the tooth row. The authors suggested that ''Allosaurus'' used its skull like a machete against prey, attacking open-mouthed, slashing flesh with its teeth, and tearing it away without splintering bones, unlike ''Tyrannosaurus'', which is thought to have been capable of damaging bones. They also suggested that the architecture of the skull could have permitted the use of different strategies against different prey; the skull was light enough to allow attacks on smaller and more agile ornithopods, but strong enough for high-impact ambush attacks against larger prey like stegosaurids and sauropods. Their interpretations were challenged by other researchers, who found no modern analogues to a hatchet attack and considered it more likely that the skull was strong to compensate for its open construction when absorbing the stresses from struggling prey. The original authors noted that ''Allosaurus'' itself has no modern equivalent, that the tooth row is well-suited to such an attack, and that articulations in the skull cited by their detractors as problematic actually helped protect the  Other aspects of feeding include the eyes, arms, and legs. The shape of the skull of ''Allosaurus'' limited potential

Other aspects of feeding include the eyes, arms, and legs. The shape of the skull of ''Allosaurus'' limited potential

It has been speculated since the 1970s that ''Allosaurus'' preyed on sauropods and other large dinosaurs by hunting in groups.

Such a depiction is common in semitechnical and popular dinosaur literature. Robert T. Bakker has extended social behavior to parental care, and has interpreted shed allosaur teeth and chewed bones of large prey animals as evidence that adult allosaurs brought food to lairs for their young to eat until they were grown, and prevented other carnivores from scavenging on the food. However, there is actually little evidence of gregarious behavior in theropods, and social interactions with members of the same species would have included antagonistic encounters, as shown by injuries to gastralia and bite wounds to skulls (the pathologic lower jaw named ''Labrosaurus ferox'' is one such possible example). Such head-biting may have been a way to establish dominance in a pack or to settle territorial disputes.

Although ''Allosaurus'' may have hunted in packs, it has been argued that ''Allosaurus'' and other theropods had largely aggressive interactions instead of cooperative interactions with other members of their own species. The study in question noted that cooperative hunting of prey much larger than an individual predator, as is commonly inferred for theropod dinosaurs, is rare among vertebrates in general, and modern

It has been speculated since the 1970s that ''Allosaurus'' preyed on sauropods and other large dinosaurs by hunting in groups.

Such a depiction is common in semitechnical and popular dinosaur literature. Robert T. Bakker has extended social behavior to parental care, and has interpreted shed allosaur teeth and chewed bones of large prey animals as evidence that adult allosaurs brought food to lairs for their young to eat until they were grown, and prevented other carnivores from scavenging on the food. However, there is actually little evidence of gregarious behavior in theropods, and social interactions with members of the same species would have included antagonistic encounters, as shown by injuries to gastralia and bite wounds to skulls (the pathologic lower jaw named ''Labrosaurus ferox'' is one such possible example). Such head-biting may have been a way to establish dominance in a pack or to settle territorial disputes.

Although ''Allosaurus'' may have hunted in packs, it has been argued that ''Allosaurus'' and other theropods had largely aggressive interactions instead of cooperative interactions with other members of their own species. The study in question noted that cooperative hunting of prey much larger than an individual predator, as is commonly inferred for theropod dinosaurs, is rare among vertebrates in general, and modern

In 2001, Bruce Rothschild and others published a study examining evidence for stress fractures and tendon avulsions in

In 2001, Bruce Rothschild and others published a study examining evidence for stress fractures and tendon avulsions in  Other pathologies reported in ''Allosaurus'' include:

* Willow breaks in two ribs

* Healed fractures in the humerus and Radius (bone), radius

* Distortion of joint surfaces in the foot, possibly due to osteoarthritis or developmental issues

* Osteopetrosis along the endosteal surface of a tibia.

* Distortions of the joint surfaces of the tail vertebrae, possibly due to osetoarthritis or developmental issues

* "[E]xtensive 'neoplastic' ankylosis of caudals", possibly due to physical trauma, as well as the fusion of chevrons to centra

* Coossification of vertebral centra near the end of the tail

* Amputation of a chevron and foot bone, both possibly a result of bites

* "[E]xtensive exostoses" in the first phalanx of the third toe

* Lesions similar to those caused by

Other pathologies reported in ''Allosaurus'' include:

* Willow breaks in two ribs

* Healed fractures in the humerus and Radius (bone), radius

* Distortion of joint surfaces in the foot, possibly due to osteoarthritis or developmental issues

* Osteopetrosis along the endosteal surface of a tibia.

* Distortions of the joint surfaces of the tail vertebrae, possibly due to osetoarthritis or developmental issues

* "[E]xtensive 'neoplastic' ankylosis of caudals", possibly due to physical trauma, as well as the fusion of chevrons to centra

* Coossification of vertebral centra near the end of the tail

* Amputation of a chevron and foot bone, both possibly a result of bites

* "[E]xtensive exostoses" in the first phalanx of the third toe

* Lesions similar to those caused by

''Allosaurus'' was the most common large theropod in the vast tract of American West, Western American fossil-bearing rock known as the Morrison Formation, accounting for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens, and as such was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food chain. The Morrison Formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet season, wet and dry seasons, and flat floodplains. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of conifers, tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the ''Araucaria''-like conifer ''Brachyphyllum''.

''Allosaurus'' was the most common large theropod in the vast tract of American West, Western American fossil-bearing rock known as the Morrison Formation, accounting for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens, and as such was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food chain. The Morrison Formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet season, wet and dry seasons, and flat floodplains. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of conifers, tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the ''Araucaria''-like conifer ''Brachyphyllum''.

The Morrison Formation has been a rich fossil hunting ground. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of Chlorophyta, green algae, fungi, mosses, Equisetum, horsetails, ferns, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Animal fossils discovered include bivalves, snails, Actinopterygii, ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, Sphenodontia, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorpha, crocodylomorphs, several species of pterosaur, numerous dinosaur species, and early mammals such as Docodonta, docodonts, Multituberculata, multituberculates, Symmetrodonta, symmetrodonts, and Triconodonta, triconodonts. Dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods ''

The Morrison Formation has been a rich fossil hunting ground. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of Chlorophyta, green algae, fungi, mosses, Equisetum, horsetails, ferns, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Animal fossils discovered include bivalves, snails, Actinopterygii, ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, Sphenodontia, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorpha, crocodylomorphs, several species of pterosaur, numerous dinosaur species, and early mammals such as Docodonta, docodonts, Multituberculata, multituberculates, Symmetrodonta, symmetrodonts, and Triconodonta, triconodonts. Dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods '' ''Allosaurus'' coexisted with fellow large theropods ''

''Allosaurus'' coexisted with fellow large theropods ''

Specimens, discussion, and references pertaining to ''Allosaurus fragilis''

at The Theropod Database

, from Pioneer: Utah's Online Library

Restoration of MOR 693 ("Big Al")

an

at Scott Hartman's Skeletal Drawing website

* * {{Authority control Allosaurids, Late Jurassic genus first appearances Late Jurassic genus extinctions Late Jurassic dinosaurs of Europe Jurassic Portugal Fossils of Portugal Lourinhã Formation Late Jurassic dinosaurs of North America Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation Paleontology in Colorado Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Utah Fossil taxa described in 1877 Taxa named by Othniel Charles Marsh Apex predators

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of large carnosaurian

Carnosauria is an extinct large group of predatory dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Starting from the 1990s, scientists have discovered some very large carnosaurs in the carcharodontosaurid family, such as ' ...

theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

(Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxford ...

to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alluding to its unique (at the time of its discovery) concave vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

. It is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(') ("different, other") and (') ("lizard / generic reptile"). The first fossil remains that could definitively be ascribed to this genus were described in 1877 by paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among ...

. As one of the first well-known theropod dinosaurs, it has long attracted attention outside of paleontological circles.

''Allosaurus'' was a large biped

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

al predator. Its skull was light, robust and equipped with dozens of sharp, serrated

Serration is a saw-like appearance or a row of sharp or tooth-like projections. A serrated cutting edge has many small points of contact with the material being cut. By having less contact area than a smooth blade or other edge, the applied p ...

teeth. It averaged in length for ''A. fragilis'', with the largest specimens estimated as being long. Relative to the large and powerful hindlimbs, its three-fingered forelimbs were small, and the body was balanced by a long and heavily muscled tail. It is classified as an allosaurid

Allosauridae is a family of medium to large bipedal, carnivorous allosauroid theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic. Allosauridae is a fairly old taxonomic group, having been first named by the American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in ...

, a type of carnosauria

Carnosauria is an extinct large group of predatory dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Starting from the 1990s, scientists have discovered some very large carnosaurs in the carcharodontosaurid family, such as '' G ...

n theropod dinosaur.

The genus has a complicated taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

, and includes at least three valid species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, the best known of which is ''A. fragilis''. The bulk of ''Allosaurus'' remains have come from North America's Morrison Formation, with material also known from Portugal. It was known for over half of the 20th century as ''Antrodemus

''Antrodemus'' ("chamber bodied") is a dubious genus of theropod dinosaur from the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian age Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Middle Park, Colorado. It contains one species, ''Antrodemus valens'', first described and named a ...

'', but a study of the abundant remains from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry

Jurassic National Monument, at the site of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, well known for containing the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils ever found, is a paleontological site located near Cleveland, Utah, in the San Raf ...

brought the name "''Allosaurus''" back to prominence and established it as one of the best-known dinosaurs.

As the most abundant large predator in the Morrison Formation, ''Allosaurus'' was at the top of the food chain, probably preying on contemporaneous large herbivorous dinosaurs, and perhaps other predators. Potential prey included ornithopod

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (), that started out as small, bipedal running grazers and grew in size and numbers until they became one of the most successful groups of herbivores in the Cretaceous wo ...

s, stegosaurid

Stegosauridae is a family of thyreophoran dinosaurs (armoured dinosaurs) within the suborder Stegosauria. The clade is defined as all species of dinosaurs more closely related to ''Stegosaurus'' than ''Huayangosaurus''.David B. Weishampel, Peter ...

s, and sauropods. Some paleontologists interpret ''Allosaurus'' as having had cooperative social behavior

Social behavior is behavior among two or more organisms within the same species, and encompasses any behavior in which one member affects the other. This is due to an interaction among those members. Social behavior can be seen as similar to an ...

, and hunting in packs, while others believe individuals may have been aggressive toward each other, and that congregations of this genus are the result of lone individuals feeding on the same carcasses.

Discovery and history

Early discoveries and research

The discovery and early study of ''Allosaurus'' is complicated by the multiplicity of names coined during theBone Wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Ac ...

of the late 19th century. The first described fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

in this history was a bone obtained secondhand by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (September 7, 1829 – December 22, 1887) was an American geologist noted for his pioneering surveying expeditions of the Rocky Mountains in the late 19th century. He was also a physician who served with the Union Ar ...

in 1869. It came from Middle Park, near Granby, Colorado

The Town of Granby is the Statutory Town that is the most populous municipality in Grand County, Colorado, United States. The town population was 2,079 at the 2020 United States Census. Granby is situated along U.S. Highway 40 in the Middle ...

, probably from Morrison Formation rocks. The locals had identified such bones as "petrified horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

hoofs". Hayden sent his specimen to Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later was a professor of natural history at Swarthmore ...

, who identified it as half of a tail vertebra, and tentatively assigned it to the European dinosaur genus ''Poekilopleuron

''Poekilopleuron'' (meaning "varied ribs") is a genus of tetanuran dinosaur, which lived during the middle Bathonian of the Jurassic, about 168 to 166 million years ago. The genus has been used under many different spelling variants, although on ...

'' as ''Poicilopleuron'' ''valens''. He later decided it deserved its own genus, ''Antrodemus''.

''Allosaurus'' itself is based on YPM 1930, a small collection of fragmentary bones including parts of three vertebrae, a rib fragment, a tooth, a toe bone, and, most useful for later discussions, the shaft of the right humerus (upper arm). Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among ...

gave these remains the formal name ''Allosaurus fragilis'' in 1877. ''Allosaurus'' comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''/'', meaning "strange" or "different" and ''/'', meaning "lizard" or "reptile". It was named 'different lizard' because its vertebrae were different from those of other dinosaurs known at the time of its discovery. The species epithet ''fragilis'' is Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for "fragile", referring to lightening features in the vertebrae. The bones were collected from the Morrison Formation of Garden Park, north of Cañon City

A canyon (from ; archaic British English spelling: ''cañon''), or gorge, is a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering and the erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales. Rivers have a natural tendency to cu ...

. Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, who were in scientific competition with each other, went on to coin several other genera based on similarly sparse material that would later figure in the taxonomy of ''Allosaurus''. These include Marsh's ''Creosaurus'' and ''Labrosaurus'', and Cope's ''Epanterias''.

In their haste, Cope and Marsh did not always follow up on their discoveries (or, more commonly, those made by their subordinates). For example, after the discovery by Benjamin Mudge

Benjamin Franklin Mudge (August 11, 1817 – November 21, 1879) was an American lawyer, geologist and teacher. Briefly the mayor of Lynn, Massachusetts, he later moved to Kansas where he was appointed the first State Geologist. He led the fi ...

of the type specimen of ''Allosaurus'' in Colorado, Marsh elected to concentrate work in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

; when work resumed at Garden Park in 1883, M. P. Felch found an almost complete ''Allosaurus'' and several partial skeletons. In addition, one of Cope's collectors, H. F. Hubbell, found a specimen in the Como Bluff

Como Bluff is a long ridge extending east–west, located between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow, Wyoming. The ridge is an anticline, formed as a result of compressional geological folding. Three geological formations, the Sundance, th ...

area of Wyoming in 1879, but apparently did not mention its completeness, and Cope never unpacked it. Upon unpacking in 1903 (several years after Cope had died), it was found to be one of the most complete theropod specimens then known, and in 1908 the skeleton, now cataloged as AMNH 5753, was put on public view. This is the well-known mount poised over a partial ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, ...

'' skeleton as if scavenging

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding ...

it, illustrated as such by Charles R. Knight. Although notable as the first free-standing mount of a theropod dinosaur, and often illustrated and photographed, it has never been scientifically described.

The multiplicity of early names complicated later research, with the situation compounded by the terse descriptions provided by Marsh and Cope. Even at the time, authors such as Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston (July 10, 1852 – August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and paleontologist who was the first to propose that birds developed flight cursorially (by running), rather than arboreally (by leaping from tr ...

suggested that too many names had been coined. For example, Williston pointed out in 1901 that Marsh had never been able to adequately distinguish ''Allosaurus'' from ''Creosaurus''. The most influential early attempt to sort out the convoluted situation was produced by Charles W. Gilmore in 1920. He came to the conclusion that the tail vertebra named ''Antrodemus'' by Leidy was indistinguishable from those of ''Allosaurus'', and ''Antrodemus'' thus should be the preferred name because, as the older name, it had priority. ''Antrodemus'' became the accepted name for this familiar genus for over 50 years, until James Henry Madsen published on the Cleveland-Lloyd specimens and concluded that ''Allosaurus'' should be used because ''Antrodemus'' was based on material with poor, if any, diagnostic features and locality information (for example, the geological formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics ( lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock exp ...

that the single bone of ''Antrodemus'' came from is unknown). "''Antrodemus''" has been used informally for convenience when distinguishing between the skull Gilmore restored and the composite skull restored by Madsen.

Cleveland-Lloyd discoveries

Although sporadic work at what became known as the

Although sporadic work at what became known as the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry

Jurassic National Monument, at the site of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, well known for containing the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils ever found, is a paleontological site located near Cleveland, Utah, in the San Raf ...

in Emery County

Emery County is a county in east-central Utah, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 10,976. Its county seat is Castle Dale, and the largest city is Huntington.

History Prehistory

Occupation of the San Rafael ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, had taken place as early as 1927, and the fossil site itself described by William L. Stokes in 1945, major operations did not begin there until 1960. Under a cooperative effort involving nearly 40 institutions, thousands of bones were recovered between 1960 and 1965, led by James Henry Madsen. The quarry is notable for the predominance of ''Allosaurus'' remains, the condition of the specimens, and the lack of scientific resolution on how it came to be. The majority of bones belong to the large theropod ''Allosaurus fragilis'' (it is estimated that the remains of at least 46 ''A. fragilis'' have been found there, out of at a minimum 73 dinosaurs), and the fossils found there are disarticulated and well-mixed. Nearly a dozen scientific papers have been written on the taphonomy

Taphonomy is the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized or preserved in the paleontological record. The term ''taphonomy'' (from Greek , 'burial' and , 'law') was introduced to paleontology in 1940 by Soviet scientist Ivan Efremov t ...

of the site, suggesting numerous mutually exclusive explanations for how it may have formed. Suggestions have ranged from animals getting stuck in a bog, to becoming trapped in deep mud, to falling victim to drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

-induced mortality around a waterhole, to getting trapped in a spring-fed pond or seep. Regardless of the actual cause, the great quantity of well-preserved ''Allosaurus'' remains has allowed this genus to be known in detail, making it among the best-known theropods. Skeletal remains from the quarry pertain to individuals of almost all ages and sizes, from less than to long, and the disarticulation is an advantage for describing bones usually found fused. Due to being one of Utah's two fossil quarries where many ''Allosaurus'' specimens have been discovered, ''Allosaurus'' was designated as the state fossil of Utah in 1988.

Recent work: 1980s–present

The period since Madsen's monograph has been marked by a great expansion in studies dealing with topics concerning ''Allosaurus'' in life (paleobiological

Paleobiology (or palaeobiology) is an interdisciplinary field that combines the methods and findings found in both the earth sciences and the life sciences. Paleobiology is not to be confused with geobiology, which focuses more on the intera ...

and paleoecological topics). Such studies have covered topics including skeletal variation, growth, skull construction, hunting methods, the brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a ve ...

, and the possibility of gregarious living and parental care. Reanalysis of old material (particularly of large 'allosaur' specimens), new discoveries in Portugal, and several very complete new specimens have also contributed to the growing knowledge base.

"Big Al" and "Big Al II"

In 1991, "Big Al" ( MOR 693), a 95% complete, partially articulated specimen of ''Allosaurus'' was discovered. It measured about 8 meters (about 26 ft) in length. MOR 693 was excavated near Shell, Wyoming, by a joint Museum of the Rockies and University of Wyoming Geological Museum team. This skeleton was discovered by a Swiss team, led by Kirby Siber. Chure and Loewen in 2020 identified the individual as a representative of the species ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''. In 1996, the same team discovered a second ''Allosaurus'', "Big Al II". This specimen, the best preserved skeleton of its kind to date, is also referred to ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''.

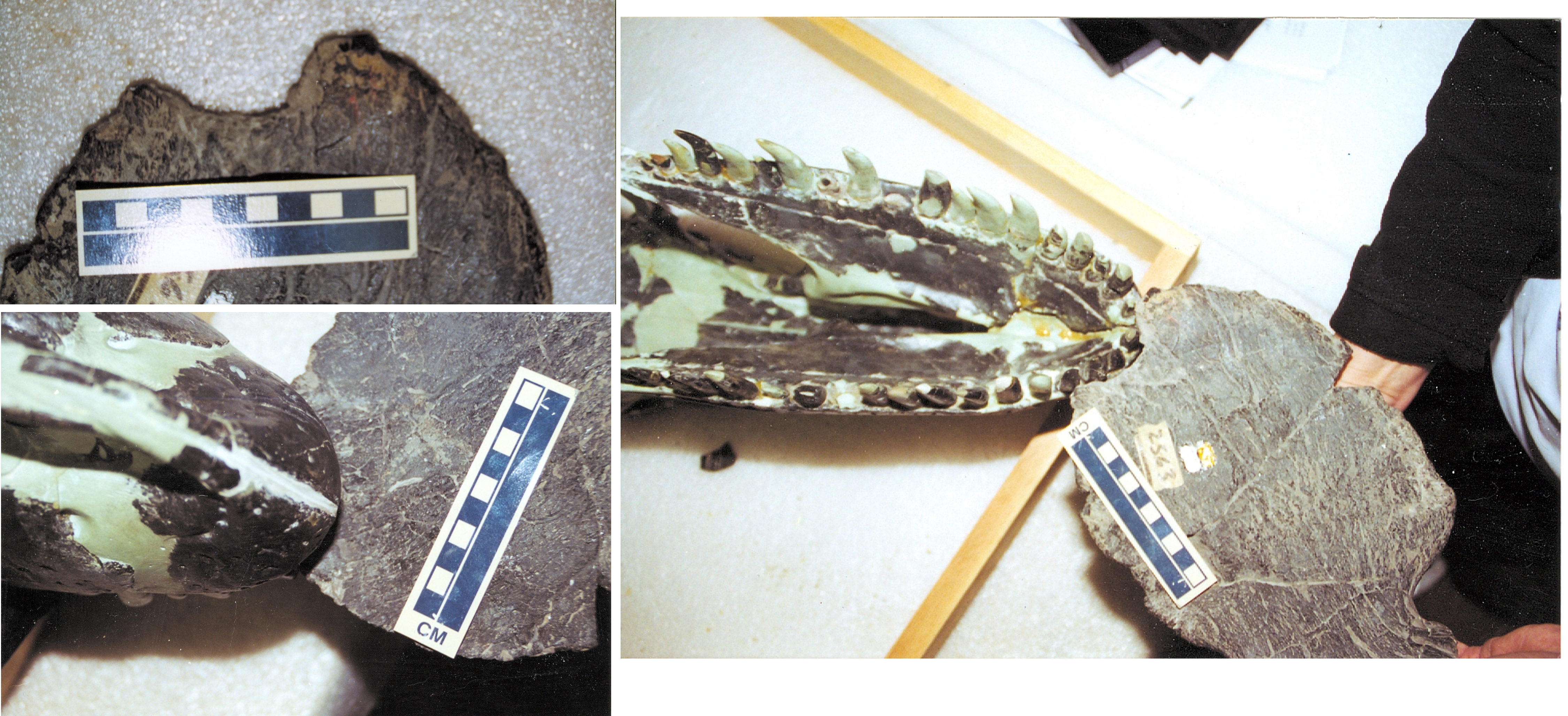

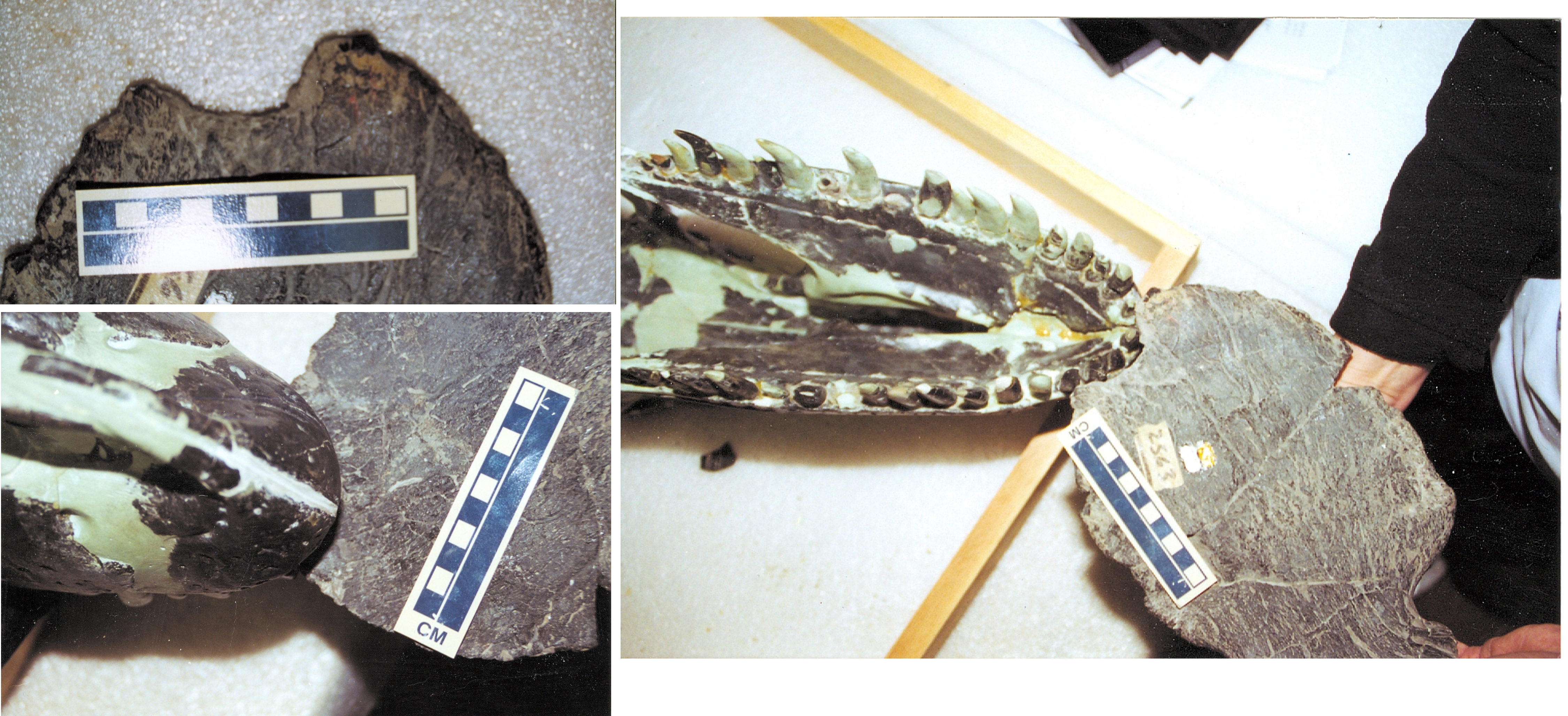

The completeness, preservation, and scientific importance of this skeleton gave "Big Al" its name; the individual itself was below the average size for ''Allosaurus fragilis'', and was a subadult estimated at only 87% grown. The specimen was described by Breithaupt in 1996. Nineteen of its bones were broken or showed signs of

In 1991, "Big Al" ( MOR 693), a 95% complete, partially articulated specimen of ''Allosaurus'' was discovered. It measured about 8 meters (about 26 ft) in length. MOR 693 was excavated near Shell, Wyoming, by a joint Museum of the Rockies and University of Wyoming Geological Museum team. This skeleton was discovered by a Swiss team, led by Kirby Siber. Chure and Loewen in 2020 identified the individual as a representative of the species ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''. In 1996, the same team discovered a second ''Allosaurus'', "Big Al II". This specimen, the best preserved skeleton of its kind to date, is also referred to ''Allosaurus jimmadseni''.

The completeness, preservation, and scientific importance of this skeleton gave "Big Al" its name; the individual itself was below the average size for ''Allosaurus fragilis'', and was a subadult estimated at only 87% grown. The specimen was described by Breithaupt in 1996. Nineteen of its bones were broken or showed signs of infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dis ...

, which may have contributed to "Big Al's" death. Pathologic

''Pathologic'' ( rus, Мор. Утопия, Mor. Utopiya, ˈmor ʊˈtopʲɪjə, , More. Utopia – a pun on Thomas More's ''Utopia'' and the Russian word for "plague") is a 2005 role-playing and survival game developed by Russian studio Ice-Pic ...

bones included five ribs, five vertebrae, and four bones of the feet; several damaged bones showed osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is an infection of bone. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The long bones of the arms and legs are most commonly involved in children e.g. the femur and humerus, while the ...

, a bone infection. A particular problem for the living animal was infection and trauma to the right foot that probably affected movement and may have also predisposed the other foot to injury because of a change in gait. Al had an infection on the first phalanx on the third toe that was afflicted by an involucrum

An involucrum (plural involucra) is a layer of new bone growth outside existing bone.

There are two main contexts:

* In pyogenic osteomyelitis where it is a layer of living bone that has formed about dead bone. It can be identified by radiograph ...

. The infection was long-lived, perhaps up to six months. Big Al Two is also known to have multiple injuries.

Species

Six species of ''Allosaurus'' have been named: ''A. amplus'', ''A. atrox'', ''A. europaeus'', the

Six species of ''Allosaurus'' have been named: ''A. amplus'', ''A. atrox'', ''A. europaeus'', the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specime ...

''A. fragilis'', ''A. jimmadseni'' and ''A. lucasi''. Among these, Daniel Chure and Mark Loewen in 2020 only recognized the species ''A. fragilis'', ''A. europaeus'', and the newly-named ''A. jimmadseni'' as being valid species.

''A. fragilis'' is the type species and was named by Marsh in 1877. It is known from the remains of at least 60 individuals, all found in the Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxford ...

– Tithonian Upper Jurassic-age Morrison Formation of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, spread across the states of Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, Oklahoma, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

, Utah, and Wyoming. Details of the humerus (upper arm) of ''A. fragilis'' have been used as diagnostic among Morrison theropods, but ''A. jimmadseni'' indicates that this is no longer the case at the species level.

''A. jimmadseni'' has been scientifically described based on two nearly complete skeletons. The first specimen to wear the identification was unearthed in Dinosaur National Monument in northeastern Utah, with the original "Big Al" individual subsequently recognized as belonging to the same species. This species differs from ''A. fragilis'' in several anatomical details, including a jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

or cheekbone with a straight lower margin. Fossils are confined to the Salt Wash Member of the Morrison Formation, with ''A. fragilis'' only found in the higher Brushy Basin Member.

''A. fragilis'', ''A. jimmadseni'', ''A. amplus'', and ''A. lucasi'' are all known from remains discovered in the Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxford ...

– Tithonian Upper Jurassic-age Morrison Formation of the United States, spread across the states of Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, Oklahoma, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

. ''A. fragilis'' is regarded as the most common, known from the remains of at least 60 individuals. For a while in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was common to recognize ''A. fragilis'' as the short-snouted species, with the long-snouted taxon being ''A. atrox''; however, subsequent analysis of specimens from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Como Bluff, and Dry Mesa Quarry showed that the differences seen in the Morrison Formation material could be attributed to individual variation. A study of skull elements from the Cleveland-Lloyd site found wide variation between individuals, calling into question previous species-level distinctions based on such features as the shape of the lacrimal horns, and the proposed differentiation of ''A. jimmadseni'' based on the shape of the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

. ''A. europaeus'' was found in the Kimmeridgian-age Porto Novo Member of the Lourinhã Formation

The Lourinhã Formation () is a fossil rich geological formation in western Portugal, named for the municipality of Lourinhã. The formation is mostly Late Jurassic in age (Kimmeridgian/Tithonian), with the top of the formation extending into the ...

, but may be the same as ''A. fragilis''.

''Allosaurus'' material from Portugal was first reported in 1999 on the basis of MHNUL/AND.001, a partial skeleton including a quadrate, vertebrae, ribs, gastralia, chevrons

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* '' Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock l ...

, part of the hips, and hindlimbs. This specimen was assigned to ''A. fragilis'', but the subsequent discovery of a partial skull and neck ( ML 415) near Lourinhã

Lourinhã () is a municipality in the District of Lisbon, in the Oeste Subregion of Portugal. The population in 2011 was 25,735, in an area of 147.17 km². The seat of the municipality is the town of Lourinhã, with a population of 8,800 inhab ...

, in the Kimmeridgian-age Porto Novo Member of the Lourinhã Formation

The Lourinhã Formation () is a fossil rich geological formation in western Portugal, named for the municipality of Lourinhã. The formation is mostly Late Jurassic in age (Kimmeridgian/Tithonian), with the top of the formation extending into the ...

, spurred the naming of the new species ''A. europaeus'' by Octávio Mateus

Octávio Mateus (born 1975) is a Portuguese dinosaur paleontologist and biologist Professor of Paleontology at the Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa. He graduated in Universidade de Évora and received his PhD at U ...

and colleagues. The species appeared earlier in the Jurassic than ''A. fragilis'' and differs from other species of ''Allosaurus'' in cranial details. However, more material may show it to be ''A. fragilis'', as originally described.

The issue of species and potential synonyms is complicated by the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

of ''Allosaurus fragilis'' (catalog number YPM 1930) being extremely fragmentary, consisting of a few incomplete vertebrae, limb bone fragments, rib fragments, and a tooth. Because of this, several scientists have interpreted the type specimen as potentially dubious, and thus the genus ''Allosaurus'' itself or at least the species ''A. fragilis'' would be a ''nomen dubium'' ("dubious name", based on a specimen too incomplete to compare to other specimens or to classify). To address this situation, Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

and Kenneth Carpenter

Kenneth Carpenter (born September 21, 1949, in Tokyo, Japan) is a paleontologist. He is the former director of the USU Eastern Prehistoric Museum and author or co-author of books on dinosaurs and Mesozoic life. His main research interests ...

(2010) submitted a petition to the ICZN to have the name "''A. fragilis"'' officially transferred to the more complete specimen USNM4734 (as a neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

).

Synonyms

''Creosaurus'', ''Epanterias'', and ''Labrosaurus'' are regarded as junior synonyms of ''Allosaurus''. Most of the species that are regarded as synonyms of ''A. fragilis'', or that were misassigned to the genus, are obscure and were based on scrappy remains. One exception is ''Labrosaurus ferox'', named in 1884 by Marsh for an oddly formed partial lower jaw, with a prominent gap in the tooth row at the tip of the jaw, and a rear section greatly expanded and turned down. Later researchers suggested that the bone was

''Creosaurus'', ''Epanterias'', and ''Labrosaurus'' are regarded as junior synonyms of ''Allosaurus''. Most of the species that are regarded as synonyms of ''A. fragilis'', or that were misassigned to the genus, are obscure and were based on scrappy remains. One exception is ''Labrosaurus ferox'', named in 1884 by Marsh for an oddly formed partial lower jaw, with a prominent gap in the tooth row at the tip of the jaw, and a rear section greatly expanded and turned down. Later researchers suggested that the bone was pathologic

''Pathologic'' ( rus, Мор. Утопия, Mor. Utopiya, ˈmor ʊˈtopʲɪjə, , More. Utopia – a pun on Thomas More's ''Utopia'' and the Russian word for "plague") is a 2005 role-playing and survival game developed by Russian studio Ice-Pic ...

, showing an injury to the living animal, and that part of the unusual form of the rear of the bone was due to plaster reconstruction. It is now regarded as an example of ''A. fragilis''.

In his 1988 book, ''Predatory Dinosaurs of the World'', the freelance dinosaurologist Gregory Paul proposed that ''A. fragilis'' had tall pointed horns and a slender build compared to a postulated second species ''A. atrox'', and was not a different sex due to rarity. ''Allosaurus atrox'' was originally named by Marsh in 1878 as the type species of its own genus, ''Creosaurus'', and is based on YPM 1890, an assortment of bones including a couple of pieces of the skull, portions of nine tail vertebrae, two hip vertebrae, an ilium, and ankle and foot bones. Although the idea of two common Morrison allosaur species was followed in some semi-technical and popular works, the 2000 thesis on Allosauridae noted that Charles Gilmore mistakenly reconstructed USNM 4734 as having a shorter skull than the specimens referred by Paul to ''atrox'', refuting supposed differences between USNM 4734 and putative ''A. atrox'' specimens like DINO 2560, AMNH 600, and AMNH 666.

"Allosaurus agilis", seen in Zittel, 1887, and Osborn, 1912, is a typographical error for ''A. fragilis.'' "Allosaurus ferox" is a typographical error by Marsh for ''A. fragilis'' in a figure caption for the partial skull YPM 1893, and YPM 1893 has been treated as a specimen of ''A fragilis''. Likewise, "Labrosaurus fragilis" is a typographical error by Marsh (1896) for ''Labrosaurus ferox''. "A. whitei" is a '' nomen nudum'' coined by Pickering in 1996 for the complete ''Allosaurus'' specimens that Paul referred to ''A. atrox''.

"Madsenius" was coined by David Lambert in 1990, for remains from Dinosaur National Monument assigned to ''Allosaurus'' or ''Creosaurus'' (a synonym of ''Allosaurus''), and was to be described by paleontologist Bob Bakker as "Madsenius trux". However, "Madsenius" is now seen as yet another synonym of ''Allosaurus'' because Bakker's action was predicated upon the false assumption of USNM 4734 being distinct from long-snouted ''Allosaurus'' due to errors in Gilmore's (1920) reconstruction of USNM 4734.

"Wyomingraptor" was informally coined by Bakker for allosaurid

Allosauridae is a family of medium to large bipedal, carnivorous allosauroid theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic. Allosauridae is a fairly old taxonomic group, having been first named by the American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in ...

remains from the Morrison Formation of the Late Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

. The remains unearthed are labeled as ''Allosaurus'' and are housed in the Tate Geological Museum. However, there has been no official description of the remains and "Wyomingraptor" has been dismissed as a ''nomen nudum'', with the remains referable to ''Allosaurus''.

Formerly assigned species and fossils

Several species initially classified within or referred to ''Allosaurus'' do not belong within the genus. ''A. medius'' was named by Marsh in 1888 for various specimens from the Early Cretaceous

Several species initially classified within or referred to ''Allosaurus'' do not belong within the genus. ''A. medius'' was named by Marsh in 1888 for various specimens from the Early Cretaceous Arundel Formation

The Arundel Formation, also known as the Arundel Clay, is a clay-rich sedimentary rock formation, within the Potomac Group, found in Maryland of the United States of America. It is of Aptian age (Lower Cretaceous). This rock unit had been econ ...

of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, although most of the remains were removed by Richard Swann Lull

Richard Swann Lull (November 6, 1867 – April 22, 1957) was an American paleontologist and Sterling Professor at Yale University who is largely remembered now for championing a non-Darwinian view of evolution, whereby mutation(s) could unl ...

to the new ornithopod species '' Dryosaurus grandis'', except for a tooth. Gilmore considered the tooth nondiagnostic but transferred it to ''Dryptosaurus

''Dryptosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of tyrannosauroid that lived approximately 67 million years ago (mya) during the latter part of the Cretaceous period, New Jersey. ''Dryptosaurus'' was a large, bipedal, ground-dwelling carnivore, that grow up to ...

'', as ''D. medius''. The referral was not accepted in the most recent review of basal tetanurans, and ''Allosaurus medius'' was simply listed as a dubious species of theropod. It may be closely related to ''Acrocanthosaurus

''Acrocanthosaurus'' ( ; ) is a genus of carcharodontosaurid dinosaur that existed in what is now North America during the Aptian and early Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous, from 113 to 110 million years ago. Like most dinosaur genera, ' ...

''.

''Allosaurus valens'' is a new combination for ''Antrodemus valens'' used by Friedrich von Huene in 1932; ''Antrodemus valens'' itself may also pertain to ''Allosaurus fragilis'', as Gilmore suggested in 1920.

''A. lucaris'', another Marsh name, was given to a partial skeleton in 1878. He later decided it warranted its own genus, ''Labrosaurus'', but this has not been accepted, and ''A. lucaris'' is also regarded as another specimen of ''A. fragilis''. ''Allosaurus lucaris'', is known mostly from vertebrae, sharing characters with ''Allosaurus''. Paul and Carpenter stated that the type specimen of this species, YPM 1931, was from a younger age than ''Allosaurus'', and might represent a different genus. However, they found that the specimen was undiagnostic, and thus ''A. lucaris'' was a ''nomen dubium''.

''Allosaurus sibiricus'' was described in 1914 by A. N. Riabinin on the basis of a bone, later identified as a partial fourth metatarsal, from the Early Cretaceous of Buryatia, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

. It was transferred to ''Chilantaisaurus'' in 1990, but is now considered a ''nomen dubium'' indeterminate beyond Theropoda.

''Allosaurus meriani'' was a new combination by George Olshevsky for ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years ...

meriani'' Greppin, 1870, based on a tooth from the Late Jurassic of Switzerland. However, a recent overview of ''Ceratosaurus'' included it in ''Ceratosaurus'' sp.

'' Apatodon mirus'', based on a scrap of vertebra Marsh first thought to be a mammalian jaw, has been listed as a synonym of ''Allosaurus fragilis''. However, it was considered indeterminate beyond Dinosauria by Chure, and Mickey Mortimer believes that the synonymy of ''Apatodon'' with ''Allosaurus'' was due to correspondence to Ralph Molnar by John McIntosh, whereby the latter reportedly found a paper saying that Othniel Charles Marsh admitted that the ''Apatodon'' holotype was actually an allosaurid dorsal vertebra.

''A. amplexus'' was named by Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

for giant Morrison allosaur remains, and included in his conception ''Saurophagus maximus'' (later ''Saurophaganax

''Saurophaganax'' ("lord of lizard-eaters") is a genus of large allosaurid dinosaur from the Morrison Formation of Late Jurassic (latest Kimmeridgian age, about 151 million years ago) Oklahoma, United States.Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999) ...

''). ''A. amplexus'' was originally coined by Cope in 1878 as the type species of his new genus ''Epanterias

''Epanterias'' is a dubious genus of theropod dinosaur from the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian age Upper Jurassic upper Morrison Formation of Garden Park, Colorado. It was described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1878. The type species is ''Epanterias amplexu ...

'', and is based on what is now AMNH 5767, parts of three vertebrae, a coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

, and a metatarsal. Following Paul's work, this species has been accepted as a synonym of ''A. fragilis''. A 2010 study by Paul and Kenneth Carpenter, however, indicates that ''Epanterias'' is temporally younger than the ''A. fragilis'' type specimen, so it is a separate species at minimum.

''A. maximus'' was a new combination by David K. Smith for Chure's ''Saurophaganax maximus'', a taxon created by Chure in 1995 for giant allosaurid remains from the Morrison of Oklahoma. These remains had been known as ''Saurophagus'', but that name was already in use, leading Chure to propose a substitute. Smith, in his 1998 analysis of variation, concluded that ''S. maximus'' was not different enough from ''Allosaurus'' to be a separate genus, but did warrant its own species, ''A. maximus''. This reassignment was rejected in a review of basal tetanurans.

There are also several species left over from the synonymizations of ''Creosaurus'' and ''Labrosaurus'' with ''Allosaurus''. '' Creosaurus potens'' was named by Lull in 1911 for a vertebra from the Early Cretaceous of Maryland. It is now regarded as a dubious theropod. ''Labrosaurus stechowi'', described in 1920 by Janensch based on isolated ''Ceratosaurus''-like teeth from the Tendaguru beds of Tanzania, was listed by Donald F. Glut as a species of ''Allosaurus'', is now considered a dubious ceratosaurian related to ''Ceratosaurus

''Ceratosaurus'' (from Greek κέρας/κέρατος, ' meaning "horn" and σαῦρος ' meaning "lizard") was a carnivorous theropod dinosaur in the Late Jurassic period ( Kimmeridgian to Tithonian). The genus was first described in 1 ...

''.Tykoski, Ronald S.; and Rowe, Timothy. (2004). "Ceratosauria", in ''The Dinosauria'' (2nd). 47–70. ''L. sulcatus'', named by Marsh in 1896 for a Morrison theropod tooth, which like ''L. stechowi'' is now regarded as a dubious ''Ceratosaurus''-like ceratosaur.

''A. tendagurensis'' was named in 1925 by

''A. tendagurensis'' was named in 1925 by Werner Janensch

Werner Ernst Martin Janensch (11 November 1878 – 20 October 1969) was a German paleontologist and geologist.

Biography

Janensch was born at Herzberg (Elster).

In addition to Friedrich von Huene, Janensch was probably Germany's most impo ...

for a partial shin (MB.R.3620) found in the Kimmeridgian-age Tendaguru Formation

The Tendaguru Formation, or Tendaguru Beds are a highly fossiliferous formation and Lagerstätte located in the Lindi Region of southeastern Tanzania. The formation represents the oldest sedimentary unit of the Mandawa Basin, overlying Neoproter ...

in Mtwara

Mtwara ( Portuguese: ''Montewara'') is the capital city of Mtwara Region in southeastern Tanzania. In the 1940s, it was planned and constructed as the export facility for the disastrous Tanganyika groundnut scheme, but was somewhat neglected whe ...

, Tanzania. Although tabulated as a tentatively valid species of ''Allosaurus'' in the second edition of the Dinosauria, subsequent studies place it as indeterminate beyond Tetanurae, either a carcharodontosaurian or megalosaurid. Although obscure, it was a large theropod, possibly around 10 meters long (33 ft) and 2.5 metric tons (2.8 short tons) in weight.

Kurzanov and colleagues in 2003 designated six teeth from Siberia as ''Allosaurus'' sp. (meaning the authors found the specimens to be most like those of ''Allosaurus'', but did not or could not assign a species to them). They were reclassified as an indeterminate theropod. Also, reports of ''Allosaurus'' in Shanxi, China go back to at least 1982. These were interpreted as ''Torvosaurus

''Torvosaurus'' () is a genus of carnivorous megalosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 165 to 148 million years ago during the late Middle and Late Jurassic period (Callovian to Tithonian stages) in what is now Colorado, Portuga ...

'' remains in 2012.

An astragalus

''Astragalus'' is a large genus of over 3,000 species of herbs and small shrubs, belonging to the legume family Fabaceae and the subfamily Faboideae. It is the largest genus of plants in terms of described species. The genus is native to tempe ...

(ankle bone) thought to belong to a species of ''Allosaurus'' was found at Cape Paterson, Victoria

Cape Paterson () is a cape and seaside village located near the town of Wonthaggi, south-east of Melbourne via the South Gippsland and Bass Highways, in the Bass Coast Shire of Gippsland, Victoria, Australia. Known originally for the discover ...

in Early Cretaceous beds in southeastern Australia. It was thought to provide evidence that Australia was a refugium for animals that had gone extinct elsewhere. This identification was challenged by Samuel Welles, who thought it more resembled that of an ornithomimid, but the original authors defended their identification. With fifteen years of new specimens and research to look at, Daniel Chure reexamined the bone and found that it was not ''Allosaurus'', but could represent an allosauroid. Similarly, Yoichi Azuma and Phil Currie

Philip John Currie (born March 13, 1949) is a Canadian palaeontologist and museum curator who helped found the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alberta and is now a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In the ...

, in their description of ''Fukuiraptor

''Fukuiraptor'' ("thief of Fukui") was a medium-sized megaraptoran theropod dinosaur of the Early Cretaceous epoch (either Barremian or Aptian) that lived in what is now Japan. ''Fukuiraptor'' is known from the Kitadani Formation and possibly ...

'', noted that the bone closely resembled that of their new genus. This specimen is sometimes referred to as " Allosaurus robustus", an informal museum name. It may have belonged to something similar to, or the same as, ''Australovenator

''Australovenator'' (meaning "southern hunter") is a genus of megaraptoran theropod dinosaur from Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous)-age Winton Formation (dated to 95 million years ago) of Australia. It is known from partial cranial and postcranial r ...

'', or it may represent an abelisaur

Abelisauroidea is typically regarded as a Cretaceous group, though the earliest abelisauridae remains are known from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina (classified as the species Eoabelisaurus mefi) and possibly Madagascar (fragmentary remains ...

.

Description

theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

, having a massive skull on a short neck, a long, slightly sloping tail, and reduced forelimbs. ''Allosaurus fragilis'', the best-known species, had an average length of and mass of , with the largest definitive ''Allosaurus'' specimen (AMNH

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 i ...

680) estimated at long, with an estimated weight of . In his 1976 monograph on ''Allosaurus'', James H. Madsen mentioned a range of bone sizes which he interpreted to show a maximum length of . As with dinosaurs in general, weight estimates are debatable, and since 1980 have ranged between , , and approximately for modal adult weight (not maximum). John Foster, a specialist on the Morrison Formation, suggests that is reasonable for large adults of ''A. fragilis'', but that is a closer estimate for individuals represented by the average-sized thigh bones he has measured. Using the subadult specimen nicknamed "Big Al", since assigned to the species ''Allosaurus jimmadseni'', researchers using computer modelling arrived at a best estimate of for the individual, but by varying parameters they found a range from approximately to approximately . ''A. europaeus'' has been measured up to in length and in body mass.

Several gigantic specimens have been attributed to ''Allosaurus'', but may in fact belong to other genera. The closely related genus ''

Several gigantic specimens have been attributed to ''Allosaurus'', but may in fact belong to other genera. The closely related genus ''Saurophaganax

''Saurophaganax'' ("lord of lizard-eaters") is a genus of large allosaurid dinosaur from the Morrison Formation of Late Jurassic (latest Kimmeridgian age, about 151 million years ago) Oklahoma, United States.Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999) ...

'' ( OMNH 1708) reached perhaps in length, and its single species has sometimes been included in the genus ''Allosaurus'' as ''Allosaurus maximus'', though recent studies support it as a separate genus. Another potential specimen of ''Allosaurus'', once assigned to the genus ''Epanterias

''Epanterias'' is a dubious genus of theropod dinosaur from the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian age Upper Jurassic upper Morrison Formation of Garden Park, Colorado. It was described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1878. The type species is ''Epanterias amplexu ...

'' (AMNH 5767), may have measured in length. A more recent discovery is a partial skeleton from the Peterson Quarry in Morrison rocks of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

; this large allosaurid may be another individual of ''Saurophaganax''.Foster, John. 2007. ''Jurassic West: the Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World''. Bloomington, Indiana:Indiana University Press. p. 117.

David K. Smith, examining ''Allosaurus'' fossils by quarry, found that the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry

Jurassic National Monument, at the site of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, well known for containing the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils ever found, is a paleontological site located near Cleveland, Utah, in the San Raf ...

(Utah) specimens are generally smaller than those from Como Bluff

Como Bluff is a long ridge extending east–west, located between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow, Wyoming. The ridge is an anticline, formed as a result of compressional geological folding. Three geological formations, the Sundance, th ...

(Wyoming) or Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU, sometimes referred to colloquially as The Y) is a private research university in Provo, Utah. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-d ...

's Dry Mesa Quarry

The Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry is situated in southwestern Colorado, United States, near the town of Delta. Its geology forms a part of the Morrison Formation and has famously yielded a great diversity of animal remains from the Jurassic Period, am ...

(Colorado), but the shapes of the bones themselves did not vary between the sites. A later study by Smith incorporating Garden Park (Colorado) and Dinosaur National Monument (Utah) specimens found no justification for multiple species based on skeletal variation; skull variation was most common and was gradational, suggesting individual variation was responsible. Further work on size-related variation again found no consistent differences, although the Dry Mesa material tended to clump together on the basis of the astragalus

''Astragalus'' is a large genus of over 3,000 species of herbs and small shrubs, belonging to the legume family Fabaceae and the subfamily Faboideae. It is the largest genus of plants in terms of described species. The genus is native to tempe ...

, an ankle bone. Kenneth Carpenter

Kenneth Carpenter (born September 21, 1949, in Tokyo, Japan) is a paleontologist. He is the former director of the USU Eastern Prehistoric Museum and author or co-author of books on dinosaurs and Mesozoic life. His main research interests ...

, using skull elements from the Cleveland-Lloyd site, found wide variation between individuals, calling into question previous species-level distinctions based on such features as the shape of the horns, and the proposed differentiation of ''A. jimmadseni'' based on the shape of the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

. A study published by Motani ''et al.,'' in 2020 suggests that ''Allosaurus'' was also sexually dimorphic in the width of the femur's head against its length.

Skull

The skull and teeth of ''Allosaurus'' were modestly proportioned for a theropod of its size. Paleontologist

The skull and teeth of ''Allosaurus'' were modestly proportioned for a theropod of its size. Paleontologist Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

gives a length of for a skull belonging to an individual he estimates at long. Each premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

(the bones that formed the tip of the snout) held five teeth with D-shaped cross-sections, and each maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

(the main tooth-bearing bones in the upper jaw) had between 14 and 17 teeth; the number of teeth does not exactly correspond to the size of the bone. Each dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(the tooth-bearing bone of the lower jaw) had between 14 and 17 teeth, with an average count of 16. The teeth became shorter, narrower, and more curved toward the back of the skull. All of the teeth had saw-like edges. They were shed easily, and were replaced continually, making them common fossils. Its skull was light, robust and equipped with dozens of sharp, serrated

Serration is a saw-like appearance or a row of sharp or tooth-like projections. A serrated cutting edge has many small points of contact with the material being cut. By having less contact area than a smooth blade or other edge, the applied p ...

teeth.