Alice In Wonderland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by

Carroll began writing the manuscript of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost. The girls and Carroll took another boat trip a month later, when he elaborated the plot to the story of Alice, and in November he began working on the manuscript in earnest.

To add the finishing touches he researched natural history in connection with the animals presented in the book, and then had the book examined by other children—particularly those of

Carroll began writing the manuscript of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost. The girls and Carroll took another boat trip a month later, when he elaborated the plot to the story of Alice, and in November he began working on the manuscript in earnest.

To add the finishing touches he researched natural history in connection with the animals presented in the book, and then had the book examined by other children—particularly those of

A young girl named Alice sits bored by a riverbank, where she suddenly spots a

A young girl named Alice sits bored by a riverbank, where she suddenly spots a  The White Rabbit appears in search of the gloves and fan. Mistaking Alice for his

The White Rabbit appears in search of the gloves and fan. Mistaking Alice for his  Noticing a door on one of the trees, Alice passes through and finds herself back in the room from the beginning of her journey. She is able to take the key and use it to open the door to the garden, which turns out to be the

Noticing a door on one of the trees, Alice passes through and finds herself back in the room from the beginning of her journey. She is able to take the key and use it to open the door to the garden, which turns out to be the

Carroll's biographer Morton N. Cohen reads ''Alice'' as a

Carroll's biographer Morton N. Cohen reads ''Alice'' as a

The manuscript was illustrated by Carroll himself who added 37 illustrations—printed in a facsimile edition in 1887.

The manuscript was illustrated by Carroll himself who added 37 illustrations—printed in a facsimile edition in 1887.

''Alice'' was published to critical praise. One magazine declared it "exquisitely wild, fantastic, ndimpossible". In the late 19th century,

''Alice'' was published to critical praise. One magazine declared it "exquisitely wild, fantastic, ndimpossible". In the late 19th century,

In 2015, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in ''

In 2015, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in ''

The first full major production of 'Alice' books during Lewis Carroll's lifetime was '' Alice in Wonderland'', an 1886

The first full major production of 'Alice' books during Lewis Carroll's lifetime was '' Alice in Wonderland'', an 1886  The 1992 musical theatre production ''Alice'' used both ''Alice'' books as its inspiration. It also employs scenes with Carroll, a young Alice Liddell, and an adult Alice Liddell, to frame the story. Paul Schmidt wrote the play, with

The 1992 musical theatre production ''Alice'' used both ''Alice'' books as its inspiration. It also employs scenes with Carroll, a young Alice Liddell, and an adult Alice Liddell, to frame the story. Paul Schmidt wrote the play, with

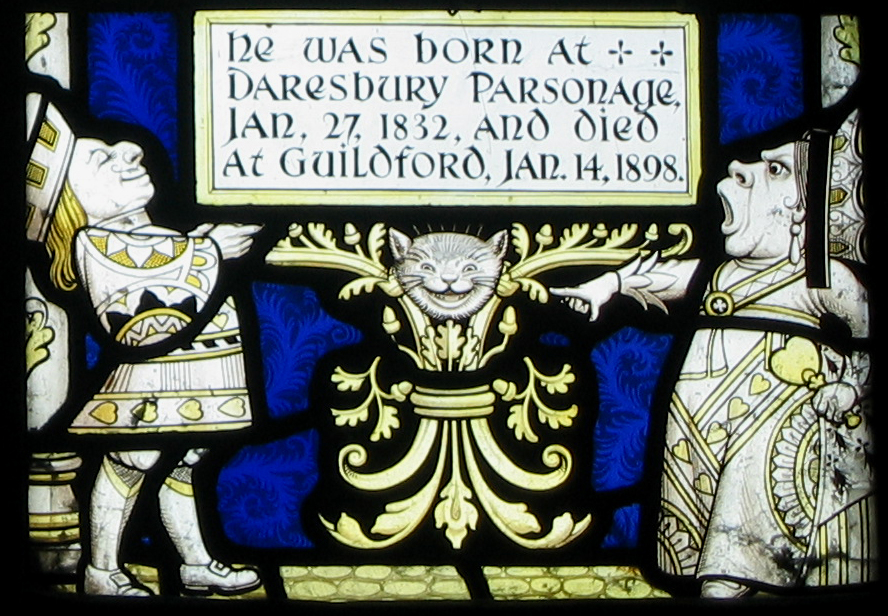

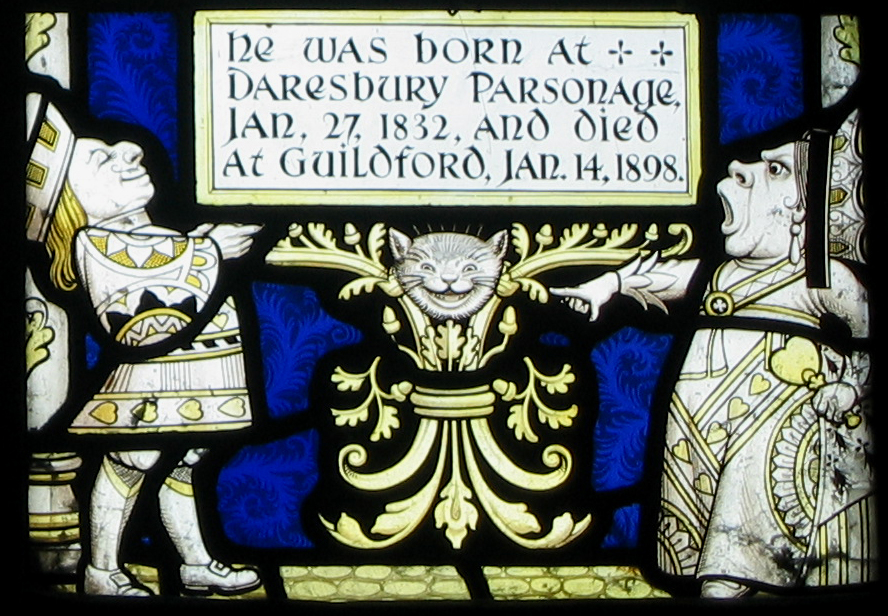

Characters from the book are depicted on the stained glass windows of Lewis Carroll's hometown church, All Saints', in

Characters from the book are depicted on the stained glass windows of Lewis Carroll's hometown church, All Saints', in

1865 British novels

1865 fantasy novels

British children's novels

British children's books

Children's books set in subterranea

Children's fantasy novels

English fantasy novels

High fantasy novels

Surreal comedy

Victorian novels

Series of children's books

Alice in Wonderland

Cultural depictions of Benjamin Disraeli

British novels adapted into films

British novels adapted into plays

Novels adapted into video games

Books about rabbits and hares

Novels about dreams

Fiction about size change

Fictional fungi

Novels set in fictional countries

Works by Lewis Carroll

Books illustrated by John Tenniel

Books illustrated by Arthur Rackham

Macmillan Publishers books

D. Appleton & Company books

Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequ ...

. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatures. It is seen as an example of the literary nonsense

Literary nonsense (or nonsense literature) is a broad categorization of literature that balances elements that make sense with some that do not, with the effect of subverting language conventions or logical reasoning. Even though the most well-k ...

genre. The artist John Tenniel

Sir John Tenniel (; 28 February 182025 February 1914)Johnson, Lewis (2003), "Tenniel, John", ''Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online'', Oxford University Press. Web. Retrieved 12 December 2016. was an English illustrator, graphic humorist and poli ...

provided 42 wood-engraved illustrations for the book.

It received positive reviews upon release and is now one of the best-known works of Victorian literature

Victorian literature refers to English literature during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). The 19th century is considered by some to be the Golden Age of English Literature, especially for British novels. It was in the Victorian era tha ...

; its narrative, structure, characters and imagery have had widespread influence on popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

and literature, especially in the fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy literature and d ...

genre. It is credited as helping end an era of didacticism

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need t ...

in children's literature

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

, inaugurating a new era in which writing for children aimed to "delight or entertain". The tale plays with logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premise ...

, giving the story lasting popularity with adults as well as with children. The titular character Alice shares her given name with Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

, a girl Carroll knew.

The book has never been out of print and has been translated into 174 languages. Its legacy covers adaptations

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the ...

for screen, radio, art, ballet, opera, musicals, theme parks, board games and video games. Carroll published a sequel in 1871 entitled ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

'' and a shortened version for young children, '' The Nursery "Alice"'', in 1890.

Background

"All in the golden afternoon..."

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' was inspired when, on 4 July 1862,Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequ ...

and Reverend Robinson Duckworth rowed up The Isis

"The Isis" () is an alternative name for the River Thames, used from its source in the Cotswolds until it is joined by the Thame at Dorchester in Oxfordshire. It derives from the ancient name for the Thames, ''Tamesis'', which in the Middle ...

in a boat with three young girls. The three girls were the daughters of scholar Henry Liddell: Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13; "Prima" in the book's prefatory verse); Alice Pleasance Liddell (aged 10; "Secunda" in the verse); and Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8; "Tertia" in the verse).

The journey began at Folly Bridge

Folly Bridge is a stone bridge over the River Thames carrying the Abingdon Road south from the centre of Oxford, England. It was erected in 1825–27, to designs of a little-known architect, Ebenezer Perry (died 1850), who practised in London.

...

, Oxford, and ended away in Godstow, Oxfordshire. During the trip Carroll told the girls a story that he described in his diary as "Alice's Adventures Under Ground" and which his journal says he "undertook to write out for Alice". Alice Liddell recalled that she asked Carroll to write it down: unlike other stories he had told her, this one she wanted to preserve. She finally got the manuscript more than two years later.

4 July was known as the " golden afternoon", prefaced in the novel as a poem. In fact, the weather around Oxford on 4 July was "cool and rather wet", although at least one scholar has disputed this claim. Scholars debate whether Carroll in fact came up with ''Alice'' during the "golden afternoon" or whether the story was developed over a longer period.

Carroll had known the Liddell children since around March 1856, when he befriended Harry Liddell. He met Lorina by early March as well. In June 1856, he took the children out on the river. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, who wrote a literary biography of Carroll, suggests that Carroll favoured Alice Pleasance Liddell in particular because her name was ripe for allusion. "Pleasance" means pleasure and the name "Alice" appeared in contemporary works including the poem "Alice Gray" by William Mee, of which Carroll wrote a parody; and Alice is a character in "Dream-Children: A Reverie", a prose piece by Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his '' Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book '' Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764� ...

. Carroll, an amateur photographer by the late 1850s, produced many photographic portraits of the Liddell children—but none more than Alice, of whom 20 survive.

Manuscript: ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground''

Carroll began writing the manuscript of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost. The girls and Carroll took another boat trip a month later, when he elaborated the plot to the story of Alice, and in November he began working on the manuscript in earnest.

To add the finishing touches he researched natural history in connection with the animals presented in the book, and then had the book examined by other children—particularly those of

Carroll began writing the manuscript of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost. The girls and Carroll took another boat trip a month later, when he elaborated the plot to the story of Alice, and in November he began working on the manuscript in earnest.

To add the finishing touches he researched natural history in connection with the animals presented in the book, and then had the book examined by other children—particularly those of George MacDonald

George MacDonald (10 December 1824 – 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet and Christian Congregational church, Congregational Minister (Christianity), minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of modern fantasy literature a ...

. Though Carroll did add his own illustrations to the original copy, on publication he was advised to find a professional illustrator so the pictures were more appealing to its audiences. He subsequently approached John Tenniel

Sir John Tenniel (; 28 February 182025 February 1914)Johnson, Lewis (2003), "Tenniel, John", ''Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online'', Oxford University Press. Web. Retrieved 12 December 2016. was an English illustrator, graphic humorist and poli ...

to reinterpret Carroll's visions through his own artistic eye, telling him that the story had been well liked by the children.

On 26 November 1864, Carroll gave Alice the handwritten manuscript of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'', with illustrations by Carroll himself, dedicating it as "A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer's Day".

The published version of ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' is about twice the length of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' and includes episodes, such as the Mad Tea-Party, that did not appear in the manuscript. The only known manuscript copy of ''Under Ground'' is held in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

. Macmillan published a facsimile of the manuscript in 1886.

Carroll began planning a print edition of the ''Alice'' story in 1863, before he gave Alice Liddell the handwritten manuscript. He wrote on 9 May 1863 that MacDonald's family had suggested he publish ''Alice''. A diary entry for 2 July says that he received a specimen page of the print edition around that date.

Plot

A young girl named Alice sits bored by a riverbank, where she suddenly spots a

A young girl named Alice sits bored by a riverbank, where she suddenly spots a White Rabbit

The White Rabbit is a fictional and anthropomorphic character in Lewis Carroll's 1865 book ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''. He appears at the very beginning of the book, in chapter one, wearing a waistcoat, and muttering "Oh dear! Oh dear! ...

with a pocket watch

A pocket watch (or pocketwatch) is a watch that is made to be carried in a pocket, as opposed to a wristwatch, which is strapped to the wrist.

They were the most common type of watch from their development in the 16th century until wristw ...

and waistcoat

A waistcoat ( UK and Commonwealth, or ; colloquially called a weskit), or vest ( US and Canada), is a sleeveless upper-body garment. It is usually worn over a dress shirt and necktie and below a coat as a part of most men's formal wear. ...

lamenting that he is late. The surprised Alice follows him down a rabbit hole, which sends her down a lengthy plummet but to a safe landing. Inside a room with a table, she finds a key to a tiny door, beyond which is a beautiful garden. As she ponders how to fit through the door, she discovers a bottle reading "Drink me". Alice hesitantly drinks a portion of the bottle's contents, and to her astonishment, she shrinks small enough to enter the door. However, she had left the key upon the table and is unable to reach it. Alice then discovers and eats a cake, which causes her to grow to a tremendous size. As the unhappy Alice bursts into tears, the passing White Rabbit flees in a panic, dropping a fan and pair of gloves. Alice uses the fan for herself, which causes her to shrink once more and leaves her swimming in a pool of her own tears. Within the pool, Alice meets a variety of animals and birds, who convene on a bank and engage in a "Caucus Race" to dry themselves. Following the end of the race, Alice inadvertently frightens the animals away by discussing her cat.

The White Rabbit appears in search of the gloves and fan. Mistaking Alice for his

The White Rabbit appears in search of the gloves and fan. Mistaking Alice for his maidservant

A handmaiden, handmaid or maidservant is a personal maid or female Domestic worker, servant. Depending on culture or historical period, a handmaiden may be of slave status or may be simply an employee. However, the term ''handmaiden'' generally ...

, the White Rabbit orders Alice to go into his house and retrieve them. Alice finds another bottle and drinks from it, which causes her to grow to such an extent that she gets stuck within the house. The White Rabbit and his neighbors attempt several methods to extract her, eventually taking to hurling pebbles that turn into small cakes. Alice eats one and shrinks herself, allowing her to flee into the forest. She meets a Caterpillar seated on a mushroom and smoking a hookah. Amidst the Caterpillar's questioning, Alice begins to admit to her current identity crisis, compounded by her inability to remember a poem. Before crawling away, the Caterpillar tells her that a bite of one side of the mushroom will make her larger, while a bite from the other side will make her smaller. During a period of trial and error, Alice's neck extends between the treetops, frightening a pigeon who mistakes her for a serpent. After shrinking to an appropriate height, Alice arrives at the home of a Duchess

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

, who owns a perpetually grinning Cheshire Cat

The Cheshire Cat ( or ) is a fictional cat popularised by Lewis Carroll in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and known for its distinctive mischievous grin. While now most often used in ''Alice''-related contexts, the association of a "Ch ...

. The Duchess's baby, whom she hands to Alice, transforms into a piglet, which Alice releases into the woods. The Cheshire Cat appears to Alice and directs her toward the Hatter

Hat-making or millinery is the design, manufacture and sale of hats and other headwear. A person engaged in this trade is called a milliner or hatter.

Historically, milliners, typically women shopkeepers, produced or imported an inventory of g ...

and March Hare

The March Hare (called Haigha in ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a character most famous for appearing in the tea party scene in Lewis Carroll's 1865 book ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''.

The main character, Alice, hypothesizes,

: "T ...

before disappearing, leaving his grin behind. Alice finds the Hatter, March Hare, and a sleepy Dormouse

A dormouse is a rodent of the family Gliridae (this family is also variously called Myoxidae or Muscardinidae by different taxonomists). Dormice are nocturnal animals found in Africa, Asia, and Europe. They are named for their long, dormant hibe ...

in the midst of an absurd tea party. The Hatter explains that it is always 6 pm (tea time), claiming that time is standing still as punishment for the Hatter trying to "kill it". A strange conversation ensues around the table, and the riddle " Why is a raven like a writing desk?" is brought forward. Eventually, Alice impatiently decides to leave, dismissing the affair as "the stupidest tea party that he hasever been to".

Noticing a door on one of the trees, Alice passes through and finds herself back in the room from the beginning of her journey. She is able to take the key and use it to open the door to the garden, which turns out to be the

Noticing a door on one of the trees, Alice passes through and finds herself back in the room from the beginning of her journey. She is able to take the key and use it to open the door to the garden, which turns out to be the croquet

Croquet ( or ; french: croquet) is a sport that involves hitting wooden or plastic balls with a mallet through hoops (often called "wickets" in the United States) embedded in a grass playing court.

Its international governing body is the W ...

court of the Queen of Hearts

The queen of hearts is a playing card in the standard 52-card deck.

Queen of Hearts or The Queen of Hearts may refer to:

Books

* "The Queen of Hearts" (poem), anonymous nursery rhyme published 1782

* ''The Queen of Hearts'', an 1859 novel by ...

, whose guard consists of living playing cards. Alice participates in a croquet game, in which hedgehogs are used as balls, flamingos are used as mallets, and soldiers act as gates. The Queen proves to be short-tempered, and she constantly orders beheadings. When the Cheshire Cat appears as only a head, the Queen orders his beheading, only to be told that such an act is impossible. Because the cat belongs to the Duchess, Alice prompts the Queen to release the Duchess from prison to resolve the matter. When the Duchess ruminates on finding morals in everything around her, the Queen dismisses her on the threat of execution. Alice then meets a Gryphon

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon ( Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail, and ...

and a weeping Mock Turtle

The Mock Turtle is a fictional character devised by Lewis Carroll from his popular 1865 book ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''. Its name is taken from a dish that was popular in the Victorian period, mock turtle soup.

''Alice's Adventures in ...

, who dance to the Lobster Quadrille while Alice recites (rather incorrectly) " 'Tis the Voice of the Lobster". The Mock Turtle sings them "Beautiful Soup" during which the Gryphon drags Alice away for an impending trial, in which the Knave of Hearts stands accused of stealing the Queen's tarts. The trial is ridiculously conducted by the King of Hearts

The king of hearts is a playing card in the standard 52-card deck.

King of Hearts may also refer to:

Games

* The King of Hearts Has Five Sons, card game that may have been a precursor to Cluedo

Books

* King of Hearts (''Alice's Adventures ...

, and the jury is composed of various animals that Alice had previously met. Alice gradually grows in size and confidence, allowing herself increasingly frequent remarks on the irrationality of the proceedings. The Queen finally commands Alice's beheading, but Alice scoffs that the Queen's guard is only a pack of cards. Although Alice holds her own for a time, the card guards soon gang up and start to swarm all over her. Alice's sister wakes her up from a dream, brushing what turns out to be some leaves from Alice's face. Alice leaves her sister on the bank to imagine all the curious happenings for herself.

Characters

The main characters in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' are the following:Character allusions

upright=1.2, Mad Tea Party.The Hatter

The Hatter is a fictional character in Lewis Carroll's 1865 book ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and its 1871 sequel ''Through the Looking-Glass''. He is very often referred to as the Mad Hatter, though this term was never used by Ca ...

In ''The Annotated Alice

''The Annotated Alice'' is a 1960 book by Martin Gardner incorporating the text of Lewis Carroll's major tales, ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and ''Through the Looking-Glass'' (1871), as well as the original illustrations by John Te ...

'', Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner (October 21, 1914May 22, 2010) was an American popular mathematics and popular science writer with interests also encompassing scientific skepticism, micromagic, philosophy, religion, and literatureespecially the writings of Lew ...

provides background information for the characters. The members of the boating party that first heard Carroll's tale show up in chapter 3 ("A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale"). Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

herself is there, while Carroll is caricatured as the Dodo (because Carroll stuttered when he spoke, he sometimes pronounced his last name as "Dodo-Dodgson"). The Duck refers to Robinson Duckworth, and the Lory and Eaglet to Alice Liddell's sisters Lorina and Edith.

Bill the Lizard may be a play on the name of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. One of Tenniel's illustrations in ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

''—the 1871 sequel to ''Alice''—depicts the character referred to as the "Man in White Paper" (whom Alice meets on a train) as a caricature of Disraeli, wearing a paper hat. The illustrations of the Lion and the Unicorn (also in ''Looking-Glass'') look like Tenniel's ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'' illustrations of William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and Disraeli, although Gardner says there is "no proof" that they were intended to represent these politicians.

Gardner has suggested that the Hatter is a reference to Theophilus Carter, an Oxford furniture dealer, and that Tenniel apparently drew the Hatter to resemble Carter, on a suggestion of Carroll's. The Dormouse tells a story about three little sisters named Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie. These are the Liddell sisters: Elsie is L.C. (Lorina Charlotte); Tillie is Edith (her family nickname is Matilda); and Lacie is an anagram of Alice.

The Mock Turtle speaks of a drawling-master, "an old conger

''Conger'' ( ) is a genus of marine congrid eels. It includes some of the largest types of eels, ranging up to 2 m (6 ft) or more in length, in the case of the European conger. Large congers have often been observed by divers during t ...

eel", who came once a week to teach "Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils". This is a reference to the art critic John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

, who came once a week to the Liddell house to teach the children drawing, sketching, and painting in oils.

The Mock Turtle also sings "Turtle Soup". This is a parody of a song called "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star", which the Liddells sang for Carroll.

Poems and songs

Carroll wrote multiple poems and songs for ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'', including: *" All in the golden afternoon..."—the prefatory verse to the book, an original poem by Carroll that recalls the rowing expedition on which he first told the story of Alice's adventures underground *" How Doth the Little Crocodile"—a parody ofIsaac Watts

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674 – 25 November 1748) was an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician. He was a prolific and popular hymn writer and is credited with some 750 hymns. His works include "When I Survey the ...

' nursery rhyme, " Against Idleness and Mischief"

*"The Mouse's Tale

"The Mouse's Tale" is a shaped poem by Lewis Carroll which appears in his 1865 novel ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''. Though no formal title for the poem is given in the text, the chapter title refers to "A Long Tale" and the Mouse introduces ...

"—an example of concrete poetry

Concrete poetry is an arrangement of linguistic elements in which the typographical effect is more important in conveying meaning than verbal significance. It is sometimes referred to as visual poetry, a term that has now developed a distinct me ...

*" You Are Old, Father William"—a parody of Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

's " The Old Man's Comforts and How He Gained Them"

*The Duchess's lullaby, "Speak roughly to your little boy..."—a parody of David Bates' "Speak Gently"

*" Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Bat"—a parody of Jane Taylor's "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star

"Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" is a popular English lullaby. The lyrics are from an early-19th-century English poem written by Jane Taylor, "The Star". The poem, which is in couplet form, was first published in 1806 in '' Rhymes for the Nursery ...

"

*" The Lobster Quadrille"—a parody of Mary Botham Howitt's " The Spider and the Fly"

*" 'Tis the Voice of the Lobster"—a parody of Isaac Watts

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674 – 25 November 1748) was an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician. He was a prolific and popular hymn writer and is credited with some 750 hymns. His works include "When I Survey the ...

' " The Sluggard"

*"Beautiful Soup"—a parody of James M. Sayles's "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star"

*" The Queen of Hearts"—an actual nursery rhyme

*"They told me you had been to her..."—White Rabbit's evidence

Writing style and themes

Symbolism

Carroll's biographer Morton N. Cohen reads ''Alice'' as a

Carroll's biographer Morton N. Cohen reads ''Alice'' as a roman à clef

''Roman à clef'' (, anglicised as ), French for ''novel with a key'', is a novel about real-life events that is overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people, and the "key" is the relationship be ...

populated with real figures from Carroll's life. The Alice of ''Alice'' is Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

; the Dodo is Carroll himself; Wonderland is Oxford; even the Mad Tea Party, according to Cohen, is a send-up of Alice's own birthday party. The critic Jan Susina rejects Cohen's account, arguing that Alice the character bears a tenuous relationship with Alice Liddell.

Beyond its refashioning of Carroll's everyday life, Cohen argues, ''Alice'' critiques Victorian ideals of childhood. It is an account of "the child's plight in Victorian upper-class society" in which Alice's mistreatment by the creatures of Wonderland reflects Carroll's own mistreatment by older people as a child.

In the eighth chapter, three cards are painting the roses on a rose tree red, because they had accidentally planted a white-rose tree that The Queen of Hearts hates. According to Wilfrid Scott-Giles

Charles Wilfrid (or Wilfred) Scott-Giles (24 October 1893 – 1982) was an English writer on heraldry and an officer of arms, who served as Fitzalan Pursuivant Extraordinary.

Life

Charles Wilfrid Giles was born in Southampton on 24 October 1893, ...

, the rose motif in ''Alice'' alludes to the English Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

: red roses symbolised the House of Lancaster, while white roses symbolised their rival House of York.

Language

''Alice'' is full of linguistic play, puns, and parodies. According to Gillian Beer, Carroll's play with language evokes the feeling of words for new readers: they "still have insecure edges and a nimbus of nonsense blurs the sharp focus of terms". The literary scholar Jessica Straley, in a work about the role of evolutionary theory in Victorian children's literature, argues that Carroll's focus on language prioritises humanism over scientism by emphasising language's role in human self-conception. Pat's "Digging for apples" is a cross-language pun, as ''pomme de terre'' (literally; "apple of the earth") means potato and ''pomme'' means apple. In the second chapter, Alice initially addresses the mouse as "O Mouse", based on her memory of the noundeclension

In linguistics, declension (verb: ''to decline'') is the changing of the form of a word, generally to express its syntactic function in the sentence, by way of some inflection. Declensions may apply to nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and ...

s "in her brother's Latin Grammar

Latin is a heavily inflected language with largely free word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case; pronouns and adjectives (including participles) are inflected for number, case, and gender; and verbs are inflected for person, ...

, 'A mouse – of a mouse – to a mouse – a mouse – O mouse!'" These words correspond to the first five of Latin's six cases, in a traditional order established by medieval grammarians: ''mus'' ( nominative), ''muris'' ( genitive), ''muri'' ( dative), ''murem'' (accusative

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘th ...

), ''(O) mus'' (vocative

In grammar, the vocative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case which is used for a noun that identifies a person (animal, object, etc.) being addressed, or occasionally for the noun modifiers (determiners, adjectives, participles, and numer ...

). The sixth case, ''mure'' (ablative

In grammar, the ablative case (pronounced ; sometimes abbreviated ) is a grammatical case for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in the grammars of various languages; it is sometimes used to express motion away from something, among other uses. ...

) is absent from Alice's recitation. Nilson has plausibly suggested that Alice's missing ablative is a pun on her father Henry Liddell's work on the standard ''A Greek-English Lexicon'' since ancient Greek does not have an ablative case. Further, Mousa (meaning muse

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the ...

) was a standard model noun in Greek books of the time in paradigms of the first declension, short-alpha noun.

Mathematics

Mathematics and logic are central to ''Alice''. As Carroll was a mathematician at Christ Church, it has been suggested that there are many references and mathematical concepts in both this story and ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

''. Literary scholar Melanie Bayley asserted in the ''New Scientist

''New Scientist'' is a magazine covering all aspects of science and technology. Based in London, it publishes weekly English-language editions in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. An editorially separate organisation publish ...

'' magazine that Carroll wrote ''Alice in Wonderland'' in its final form as a satire of mid-19th century mathematics.

Eating and devouring

Carina Garland notes how the world is "expressed via representations of food and appetite", naming Alice's frequent desire for consumption (of both food and words), her 'Curious Appetites'. Often, the idea of eating coincides to make gruesome images. After the riddle "Why is a raven like a writing-desk?", the Hatter claims that Alice might as well say, "I see what I eat…I eat what I see" and so the riddle's solution, put forward by Boe Birns, could be that "A raven eats worms; a writing desk is worm-eaten"; this idea of food encapsulates idea of life feeding on life itself, for the worm is being eaten and then becomes the eater a horrific image of mortality. Nina Auerbach discusses how the novel revolves around eating and drinking which "motivates much of her lice'sbehaviour", for the story is essentially about things "entering and leaving her mouth". The animals of Wonderland are of particular interest, for Alice's relation to them shifts constantly because, as Lovell-Smith states, Alice's changes in size continually reposition her in the food chain, serving as a way to make her acutely aware of the 'eat or be eaten' attitude that permeates Wonderland.Nonsense

''Alice'' is an example of theliterary nonsense

Literary nonsense (or nonsense literature) is a broad categorization of literature that balances elements that make sense with some that do not, with the effect of subverting language conventions or logical reasoning. Even though the most well-k ...

genre. According to Humphrey Carpenter

Humphrey William Bouverie Carpenter (29 April 1946 – 4 January 2005) was an English biographer, writer, and radio broadcaster. He is known especially for his biographies of J. R. R. Tolkien and other members of the literary society the Inkl ...

, ''Alice'' brand of nonsense embraces the nihilistic and existential. Characters in nonsensical episodes such as the Mad Tea Party, in which it is always the same time, go on posing paradoxes that are never resolved.

Rules and games

Wonderland is a rule-bound world, but its rules are not those of our world. The literary scholar Daniel Bivona writes that ''Alice'' is characterised by "gamelike social structures". She trusts in instructions from the beginning, drinking from the bottle labelled "drink me" after recalling, during her descent, that children who do not follow the rules often meet terrible fates. Unlike the creatures of Wonderland, who approach their world's wonders uncritically, Alice continues to look for rules as the story progresses. Gillian Beer suggests that Alice, the character, looks for rules to soothe her anxiety, while Carroll may have hunted for rules because he struggled with the implications of thenon-Euclidean geometry

In mathematics, non-Euclidean geometry consists of two geometries based on axioms closely related to those that specify Euclidean geometry. As Euclidean geometry lies at the intersection of metric geometry and affine geometry, non-Euclidean g ...

then in development.

Illustrations

The manuscript was illustrated by Carroll himself who added 37 illustrations—printed in a facsimile edition in 1887.

The manuscript was illustrated by Carroll himself who added 37 illustrations—printed in a facsimile edition in 1887. John Tenniel

Sir John Tenniel (; 28 February 182025 February 1914)Johnson, Lewis (2003), "Tenniel, John", ''Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online'', Oxford University Press. Web. Retrieved 12 December 2016. was an English illustrator, graphic humorist and poli ...

provided 42 wood-engraved illustrations for the published version of the book. The first print run was destroyed (or sold to the US) at Carroll's request because he was dissatisfied with the quality. There are only 22 known first edition copies in existence. The book was reprinted and published in 1866. Tenniel's detailed black-and-white drawings remain the definitive depiction of the characters.

Tenniel's illustrations of Alice do not portray the real Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

, who had dark hair and a short fringe. ''Alice'' has provided a challenge for other illustrators, including those of 1907 by Charles Pears and the full series of colour plates and line-drawings by Harry Rountree published in the (inter-War) Children's Press (Glasgow) edition. Other significant illustrators include: Arthur Rackham

Arthur Rackham (19 September 1867 – 6 September 1939) was an English book illustrator. He is recognised as one of the leading figures during the Golden Age of British book illustration. His work is noted for its robust pen and ink drawings, ...

(1907), Willy Pogany (1929), Mervyn Peake

Mervyn Laurence Peake (9 July 1911 – 17 November 1968) was an English writer, artist, poet, and illustrator. He is best known for what are usually referred to as the '' Gormenghast'' books. The four works were part of what Peake conceived ...

(1946), Ralph Steadman

Ralph Idris Steadman (born 15 May 1936) is a British illustrator best known for his collaboration and friendship with the American writer Hunter S. Thompson. Steadman is renowned for his political and social caricatures, cartoons and picture ...

(1967), Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarre images in ...

(1969), Graham Overden (1969), Max Ernst

Max Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealis ...

(1970), Peter Blake (1970), Tove Jansson

Tove Marika Jansson (; 9 August 1914 – 27 June 2001) was a Swedish-speaking Finnish author, novelist, painter, illustrator and comic strip author. Brought up by artistic parents, Jansson studied art from 1930 to 1938 in Stockholm, Helsinki and ...

(1977), Anthony Browne (1988), Helen Oxenbury

Helen Gillian Oxenbury (born 1938) is an English illustrator and writer of children's picture books. She lives in North London. She has twice won the annual Kate Greenaway Medal, the British librarians' award for illustration and been runner-up ...

(1999), and Lisbeth Zwerger

Lisbeth Zwerger (born 26 May 1954) is an Austrian illustrator of children's books. For her "lasting contribution to children's literature" she received the international Hans Christian Andersen Medal in 1990.

Zwerger was born in Vienna in 1954. ...

(1999).

Publication history

Carroll first met Alexander Macmillan, a high-powered London publisher, on 19 October 1863. His firm,Macmillan Publishers

Macmillan Publishers (occasionally known as the Macmillan Group; formally Macmillan Publishers Ltd and Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC) is a British publishing company traditionally considered to be one of the 'Big Five' English language publ ...

, agreed to publish ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' by sometime in 1864. Carroll financed the initial print run, possibly because it gave him more editorial authority than other financing methods. He managed publication details such as typesetting and engaged illustrators and translators.

Macmillan had published ''The Water-Babies'', also a children's fantasy, in 1863, and suggested its design as a basis for ''Alice''. Carroll saw a specimen copy in May 1865. 2,000 copies were printed by July but John Tenniel

Sir John Tenniel (; 28 February 182025 February 1914)Johnson, Lewis (2003), "Tenniel, John", ''Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online'', Oxford University Press. Web. Retrieved 12 December 2016. was an English illustrator, graphic humorist and poli ...

, the illustrator, objected to their quality and Carroll instructed Macmillan to halt publication so they could be reprinted. In August, he engaged Richard Clay as an alternative printer for a new run of 2,000. The reprint cost £600, paid entirely by Carroll. He received the first copy of Clay's reprint on 9 November 1865.

Macmillan finally published the revised first edition, printed by Richard Clay, in November 1865. Carroll requested a red binding, deeming it appealing to young readers. A new edition, released in December of the same year for the Christmas market, but carrying an 1866 date, was quickly printed. The text blocks of the original edition were removed from the binding and sold with Carroll's permission to the New York publishing house of D. Appleton & Company. The binding for the Appleton ''Alice'' was identical to the 1866 Macmillan ''Alice'', except for the publisher's name at the foot of the spine. The title page of the Appleton ''Alice'' was an insert cancelling the original Macmillan title page of 1865, and bearing the New York publisher's imprint and the date 1866.

The entire print run sold out quickly. ''Alice'' was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike. Oscar Wilde was a fan. Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

was also an avid reader of the book. She reportedly enjoyed ''Alice'' enough that she asked for Carroll's next book, which turned out to be a mathematical treatise; Carroll denied this. The book has never been out of print. ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' has been translated into 174 languages.

Publication timeline

The following list is a timeline of major publication events related to ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'': *1869: Published in German as ''Alice's Abenteuer im Wunderland'', translated by Antonie Zimmermann. *1869: Published in French as ''Aventures d'Alice au pays des merveilles'', translated by Henri Bué. *1870: Published in Swedish as ''Alice's Äventyr i Sagolandet'', translated by Emily Nonnen. *1871: Carroll meets another Alice, Alice Raikes, during his time in London. He talks with her about her reflection in a mirror, leading to the sequel, ''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

'', which sells even better.

*1872: Published in Italian as ''Le Avventure di Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie'', translated by Teodorico Pietrocòla Rossetti.

*1886: Carroll publishes a facsimile of the earlier ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' manuscript.

*1890: Carroll publishes '' The Nursery "Alice"'', an abridged version, around Easter.

*1905: Mrs J. C. Gorham publishes '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Retold in Words of One Syllable'' in a series of such books published by A. L. Burt

A. L. Burt (incorporated in 1902 as A. L. Burt Company) was a New York City-based book publishing house from 1883 until 1937. It was founded by Albert Levi Burt, a 40-year-old from Massachusetts who had come to recognize the demand for inexpen ...

Company, aimed at young readers.

*1906: Published in Finnish as ''Liisan seikkailut ihmemaailmassa'', translated by Anni Swan.

*1907: Copyright on ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' expires in the UK, entering the tale into the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because those rights have expired, ...

.

*1910: Published in Esperanto as ''La Aventuroj de Alicio en Mirlando,'' translated by E. L. Kearney.

*1915: Alice Gerstenberg's stage adaptation premieres.

*1928: The manuscript of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' written and illustrated by Carroll, which he had given to Alice Liddell, was sold at Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

in London on 3 April. It sold to Philip Rosenbach of Philadelphia for , a world record for the sale of a manuscript at the time; the buyer later presented it to the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

(where the manuscript remains) as an appreciation for Britain's part in two World Wars.

*1960: American writer Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner (October 21, 1914May 22, 2010) was an American popular mathematics and popular science writer with interests also encompassing scientific skepticism, micromagic, philosophy, religion, and literatureespecially the writings of Lew ...

publishes a special edition, ''The Annotated Alice

''The Annotated Alice'' is a 1960 book by Martin Gardner incorporating the text of Lewis Carroll's major tales, ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and ''Through the Looking-Glass'' (1871), as well as the original illustrations by John Te ...

''.

*1988: Lewis Carroll and Anthony Browne, illustrator of an edition from Julia MacRae Books, wins the Kurt Maschler Award.

*1998: Carroll's own copy of Alice, one of only six surviving copies of the 1865 first edition, is sold at an auction for US$1.54 million to an anonymous American buyer, becoming the most expensive children's book (or 19th-century work of literature) ever sold to that point.

*1999: Lewis Carroll and Helen Oxenbury

Helen Gillian Oxenbury (born 1938) is an English illustrator and writer of children's picture books. She lives in North London. She has twice won the annual Kate Greenaway Medal, the British librarians' award for illustration and been runner-up ...

, illustrator of an edition from Walker Books

Walker Books is a British publisher of children's books, founded in 1978 by Sebastian Walker, Amelia Edwards, and Wendy Boase.

In 1991, the success of Walker Books' ''Where's Wally?'' series enabled the company to expand into the American ma ...

, win the Kurt Maschler Award for integrated writing and illustration.

*2008: Folio publishes ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' facsimile edition

A facsimile (from Latin ''fac simile'', "to make alike") is a copy or reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print, or other item of historical value that is as true to the original source as possible. It differs from other forms of r ...

(limited to 3,750 copies, boxed with ''The Original Alice'' pamphlet).

*2009: Children's book collector and former American football player Pat McInally

John Patrick McInally (born May 7, 1953) is an American former football player who was a punter and wide receiver for the Cincinnati Bengals of the National Football League (NFL).

McInally was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame i ...

reportedly sold Alice Liddell's own copy at auction for US$115,000.

Reception

''Alice'' was published to critical praise. One magazine declared it "exquisitely wild, fantastic, ndimpossible". In the late 19th century,

''Alice'' was published to critical praise. One magazine declared it "exquisitely wild, fantastic, ndimpossible". In the late 19th century, Walter Besant

Sir Walter Besant (14 August 1836 – 9 June 1901) was an English novelist and historian. William Henry Besant was his brother, and another brother, Frank, was the husband of Annie Besant.

Early life and education

The son of wine merchant Willi ...

wrote that ''Alice in Wonderland'' "was a book of that extremely rare kind which will belong to all the generations to come until the language becomes obsolete".

F. J. Harvey Darton argued in a 1932 book that ''Alice'' ended an era of didacticism

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need t ...

in children's literature

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

, inaugurating a new era in which writing for children aimed to "delight or entertain". In 2014, Robert McCrum

John Robert McCrum (born 7 July 1953) is an English writer and editor, holding senior editorial positions at Faber and Faber over seventeen years, followed by a long association with ''The Observer''.

Early life

The son of Michael William McC ...

named ''Alice'' "one of the best loved in the English canon" and called it "perhaps the greatest, possibly most influential, and certainly the most world-famous Victorian English fiction". A 2020 review in ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' states: "The book changed young people's literature. It helped to replace stiff Victorian didacticism with a looser, sillier, nonsense style that reverberated through the works of language-loving 20th-century authors as different as James Joyce, Douglas Adams and Dr. Seuss." The protagonist of the story, Alice, has been recognised as a cultural icon

A cultural icon is a person or an artifact that is identified by members of a culture as representative of that culture. The process of identification is subjective, and "icons" are judged by the extent to which they can be seen as an authentic ...

. In 2006, ''Alice in Wonderland'' was named among the icons of England in a public vote.

Adaptations and influence

Books for children in the ''Alice'' mould emerged as early as 1869 and continued to appear throughout the late 19th century. Released in 1903, the British silent film, '' Alice in Wonderland'', was the first screen adaptation of the book. In 2015, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in ''

In 2015, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' wrote,

Labelled "a dauntless, no-nonsense heroine

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''hero ...

" by ''The Guardian'', the character of the plucky, yet proper, Alice has proven immensely popular and inspired similar heroines in literature and pop culture, many also named Alice in homage. The book has inspired numerous film and television adaptations which have multiplied as the original work is now in the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because those rights have expired, ...

in all jurisdictions. Musical works inspired by ''Alice'' includes The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developmen ...

' single "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds

"Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1967 album ''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band''. It was written primarily by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnersh ...

", with songwriter John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

attributing the song's fantastical imagery to his reading of Carroll's ''Alice in Wonderland'' books. A popular figure in Japan since the country opened up to the West in the late 19th century, Alice has been a popular subject for writers of manga and a source of inspiration for Japanese fashion, in particular Lolita fashion

is a subculture from Japan that is highly influenced by Victorian fashion, Victorian clothing and styles from the Rococo period. A very distinctive property of Lolita fashion is the aesthetic of Kawaii, cuteness. This clothing subculture can ...

.

Live performance

The first full major production of 'Alice' books during Lewis Carroll's lifetime was '' Alice in Wonderland'', an 1886

The first full major production of 'Alice' books during Lewis Carroll's lifetime was '' Alice in Wonderland'', an 1886 musical play

Musical theatre is a form of theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance. The story and emotional content of a musical – humor, pathos, love, anger – are communicated through words, music, movement ...

in London's West End by Henry Savile Clark (book) and Walter Slaughter (music), which played at the Prince of Wales Theatre

The Prince of Wales Theatre is a West End theatre in Coventry Street, near Leicester Square in London. It was established in 1884 and rebuilt in 1937, and extensively refurbished in 2004 by Sir Cameron Mackintosh, its current owner. The theatre ...

. Twelve-year-old actress Phoebe Carlo

Phoebe Ellen Carlo (30 May 1874–1898) was an English actress of the late Victorian era. She is most notable for playing Alice in the musical '' Alice in Wonderland'' (1886), making her the first actress to play the titular character in a p ...

(the first to play Alice) was personally selected by Carroll for the role. Carroll attended a performance on 30 December 1886, writing in his diary he enjoyed it. The musical was frequently revived during West End Christmas seasons during the four decades after its premiere, including a London production at the Globe Theatre in 1888, with Isa Bowman

Isa Bowman (1874–1958) was an actress, a close friend of Lewis Carroll and author of a memoir about his life, ''The Story of Lewis Carroll, Told for Young People by the Real Alice in Wonderland''.

She met Carroll in 1886 when she played a smal ...

as Alice.

As the book and its sequel are Carroll's most widely recognised works, they have also inspired numerous live performances, including plays, operas, ballets, and traditional English pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speaking ...

s. These works range from fairly faithful adaptations to those that use the story as a basis for new works. Eva Le Gallienne

Eva Le Gallienne (January 11, 1899 – June 3, 1991) was a British-born American stage actress, producer, director, translator, and author. A Broadway star by age 21, Le Gallienne gave up her Broadway appearances to devote herself to founding t ...

's stage adaptation of the ''Alice'' books premiered on 12 December 1932 and ended its run in May 1933. The production has been revived in New York in 1947 and 1982. Joseph Papp

Joseph Papp (born Joseph Papirofsky; June 22, 1921 – October 31, 1991) was an American theatrical producer and director. He established The Public Theater in what had been the Astor Library Building in Lower Manhattan. There Papp created ...

staged ''Alice in Concert'' at the Public Theater

The Public Theater is a New York City arts organization founded as the Shakespeare Workshop in 1954 by Joseph Papp, with the intention of showcasing the works of up-and-coming playwrights and performers.Epstein, Helen. ''Joe Papp: An American ...

in New York City in 1980. Elizabeth Swados

Elizabeth Swados (February 5, 1951 – January 5, 2016) was an American writer, composer, musician, and theatre director. Swados received Tony Award nominations for Best Musical, Best Direction of a Musical, Best Book of a Musical, Best Origin ...

wrote the book, lyrics, and music. Based on both ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and ''Through the Looking-Glass'', Papp and Swados had previously produced a version of it at the New York Shakespeare Festival

Shakespeare in the Park (or Free Shakespeare in the Park) is a theatrical program that stages productions of Shakespearean plays at the Delacorte Theater, an open-air theater in New York City's Central Park. The theater and the productions ar ...

. Meryl Streep

Mary Louise Meryl Streep (born June 22, 1949) is an American actress. Often described as "the best actress of her generation", Streep is particularly known for her versatility and accent adaptability. She has received numerous accolades throu ...

played Alice, the White Queen, and Humpty Dumpty. The cast also included Debbie Allen, Michael Jeter

Robert Michael Jeter (; August 26, 1952 – March 30, 2003) was an American actor. His television roles included Herman Stiles on the sitcom ''Evening Shade'' from 1990 until 1994 and Mr. Noodle's brother, Mister Noodle, on the ''Elmo's World'' ...

, and Mark Linn-Baker

Mark Linn-Baker (born June 17, 1954) is an American actor and director who played Benjy Stone in the film ''My Favorite Year'' and Larry Appleton in the television sitcom '' Perfect Strangers''.

Early life and education

Mark Linn-Baker was bo ...

. Performed on a bare stage with the actors in modern dress, the play is a loose adaptation, with song styles ranging the globe. A community theatre production of Alice was Olivia de Havilland

Dame Olivia Mary de Havilland (; July 1, 1916July 26, 2020) was a British-American actress. The major works of her cinematic career spanned from 1935 to 1988. She appeared in 49 feature films and was one of the leading actresses of her time. ...

's first foray onto the stage.

The 1992 musical theatre production ''Alice'' used both ''Alice'' books as its inspiration. It also employs scenes with Carroll, a young Alice Liddell, and an adult Alice Liddell, to frame the story. Paul Schmidt wrote the play, with

The 1992 musical theatre production ''Alice'' used both ''Alice'' books as its inspiration. It also employs scenes with Carroll, a young Alice Liddell, and an adult Alice Liddell, to frame the story. Paul Schmidt wrote the play, with Tom Waits

Thomas Alan Waits (born December 7, 1949) is an American musician, composer, songwriter, and actor. His lyrics often focus on the underbelly of society and are delivered in his trademark deep, gravelly voice. He worked primarily in jazz during ...

and Kathleen Brennan

Kathleen Patricia Brennan (born 1955) is an American musician, songwriter, record producer, and artist. She is known for her work as a co-writer, producer, and influence on the work of her husband Tom Waits.

Biography

Brennan was born in Cork, ...

writing the music. Although the original production in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, Germany, received only a small audience, Tom Waits released the songs as the album '' Alice'' in 2002.

The English composer Joseph Horovitz

Joseph Horovitz (26 May 1926 – 9 February 2022) was an Austrian-born British composer and conductor best known for his 1970 pop cantata ''Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo'', which achieved widespread popularity in schools. Horovitz also compo ...

composed an ''Alice in Wonderland'' ballet commissioned by the London Festival Ballet

English National Ballet is a classical ballet company founded by Dame Alicia Markova and Sir Anton Dolin as London Festival Ballet and based in London, England. Along with The Royal Ballet, Birmingham Royal Ballet, Northern Ballet and Scottis ...

in 1953. It was performed frequently in England and the US. A ballet by Christopher Wheeldon and Nicholas Wright commissioned for The Royal Ballet

The Royal Ballet is a British internationally renowned classical ballet company, based at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, England. The largest of the five major ballet companies in Great Britain, the Royal Ballet was founded in ...

entitled ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' premiered in February 2011 at the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Ope ...

in London. The ballet was based on the novel Wheeldon grew up reading as a child and is generally faithful to the original story, although some critics claimed it may have been too faithful. Gerald Barry's 2016 one-act opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a libr ...

, '' Alice's Adventures Under Ground'', first staged in 2020 at the Royal Opera House, is a conflation of the two ''Alice'' books.

Commemoration

Characters from the book are depicted on the stained glass windows of Lewis Carroll's hometown church, All Saints', in

Characters from the book are depicted on the stained glass windows of Lewis Carroll's hometown church, All Saints', in Daresbury

Daresbury is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Halton and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. At the 2001 census it had a population of 216, increasing to 246 by the 2011 census.

History

The name means "Deor's fo ...

, Cheshire. Another commemoration of Carroll's work in his home county of Cheshire is the granite sculpture, The Mad Hatter's Tea Party, located in Warrington. International works based on the book include the Alice in Wonderland statue in Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated ...

, New York, and the Alice statue in Rymill Park

Rymill Park / Murlawirrapurka (previously spelt Mullawirraburka), and numbered as Park 14, is a recreation park located in the East Park Lands of the South Australian capital of Adelaide. There is an artificial lake with rowboats for hire, a ...

, Adelaide, Australia. In 2015, ''Alice'' characters featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of the book.

See also

* ''Through the Looking Glass'' * Down the rabbit hole * Translations of ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' * Translations of ''Through the Looking-Glass''References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Text

* * *Audio

* * {{Authority control