Alfred Nobel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

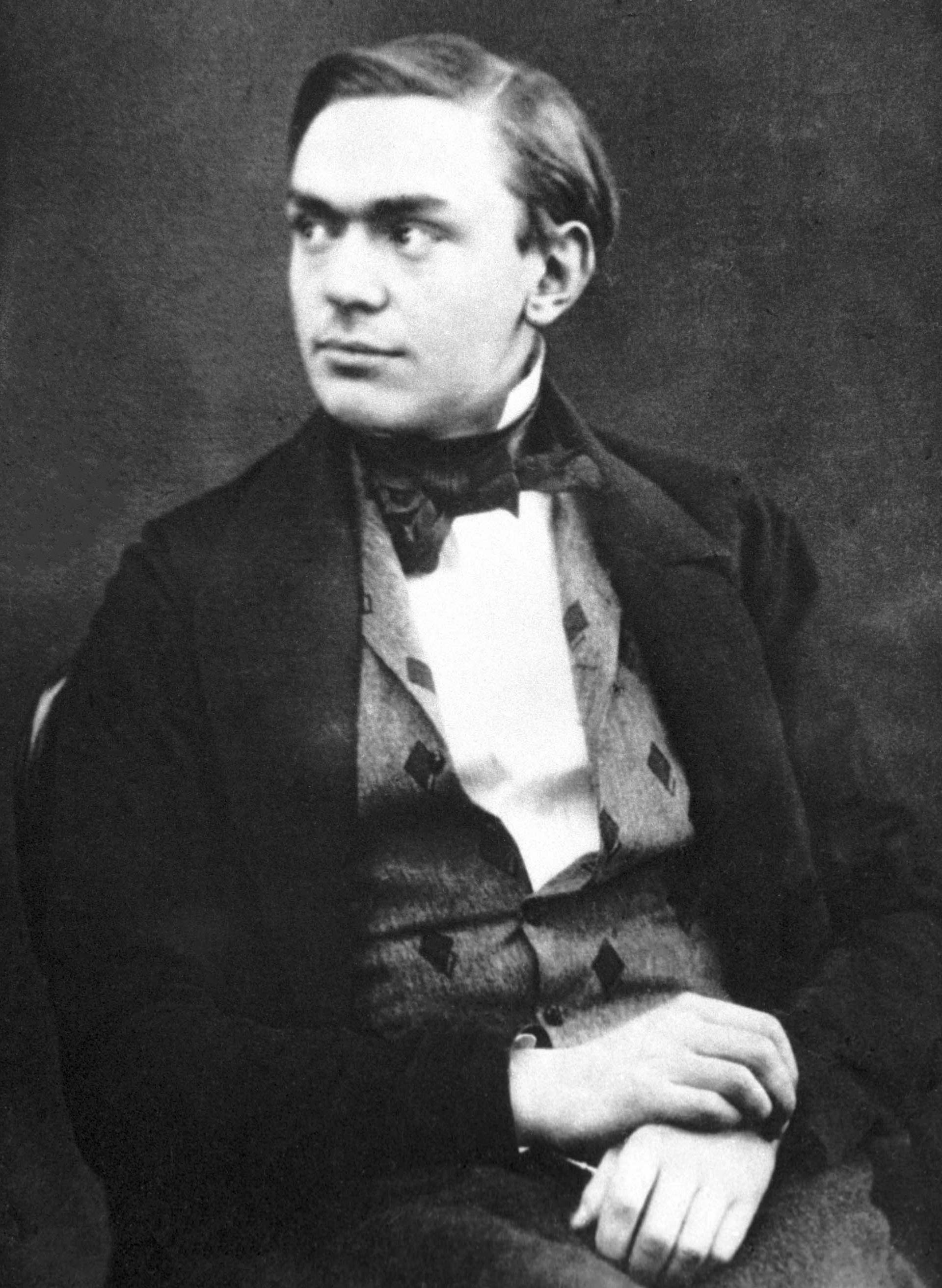

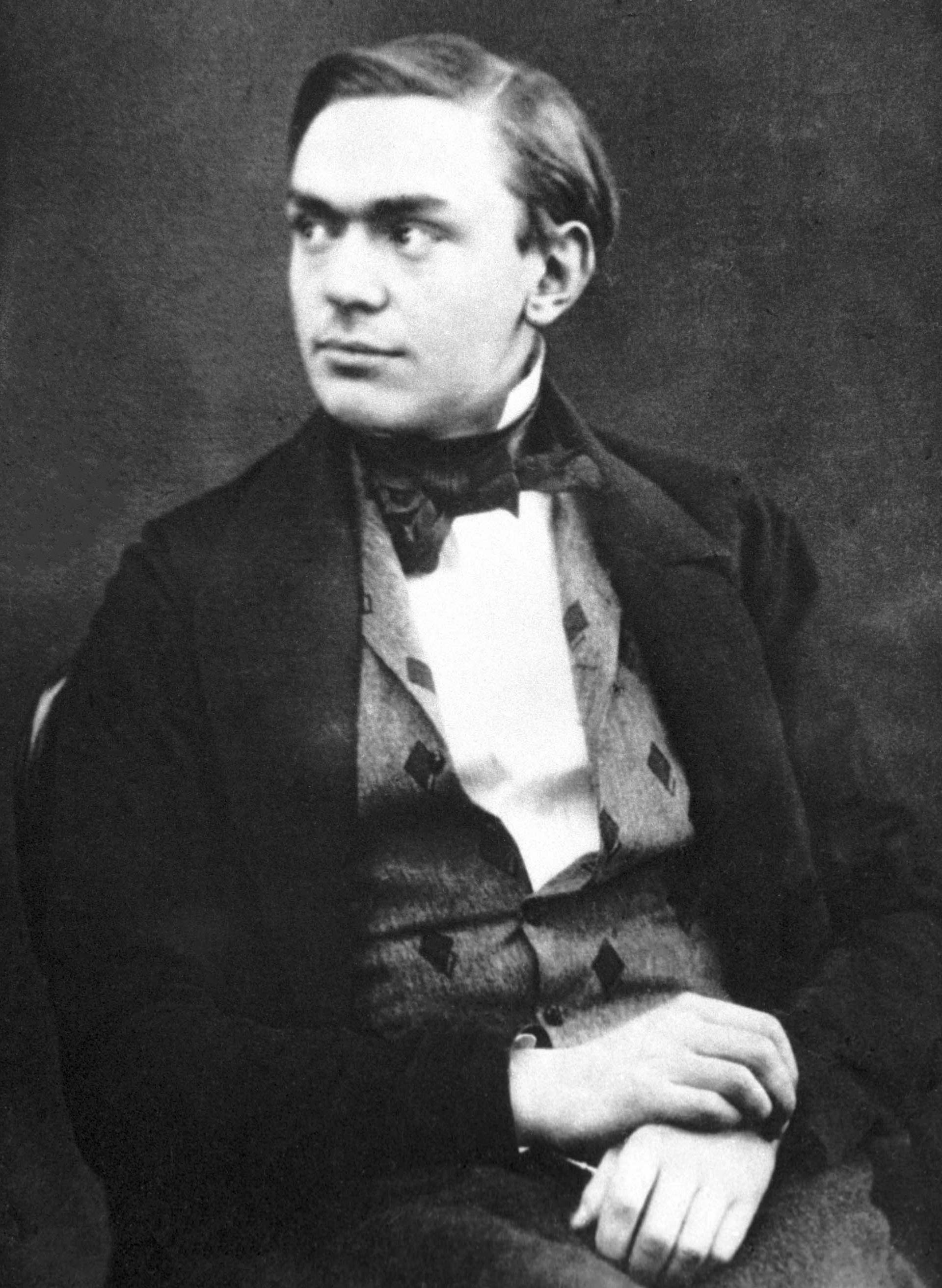

Alfred Bernhard Nobel ( , ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedish

Following various business failures, Nobel's father moved to

Following various business failures, Nobel's father moved to

In 1894, when he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, the

In 1894, when he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, the

The family factory produced

The family factory produced

Nobel was accused of high treason against France for selling

Nobel was accused of high treason against France for selling

Thomas Bertelman

and Professor

J.S.Co. "Humanistica"

1990–1991). The abstract metal sculpture was designed by local artists Sergey Alipov and Pavel Shevchenko, and appears to be an explosion or branches of a tree. Petrogradskaya Embankment is the street where Nobel's family lived until 1859. Criticism of Nobel focuses on his leading role in weapons manufacturing and sales, and some question his motives in creating his prizes, suggesting they are intended to improve his reputation.How ‘merchant of death’ Alfred Nobel became a champion of peace

in '' The Local'' 4 October 2010

Alfred Nobel – Man behind the Prizes

Nobelprize.org

* ttp://azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/ai102_folder/102_articles/102_nobels_asbrink.html "The Nobels in Baku" in ''Azerbaijan International'', Vol 10.2 (Summer 2002), 56–59.

The Nobel Prize in Postage Stamps

* A German branch or followup ''(German)'' * *

Alfred Nobel and his unknown coworker

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nobel, Alfred 1833 births 1896 deaths Burials at Norra begravningsplatsen Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, engineer, inventor, businessman, and philanthropist. He is best known for having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

, though he also made several important contributions to science, holding 355 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

s in his lifetime. Nobel's most famous invention was dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

, a safer and easier means of harnessing the explosive power of nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

; it was patented in 1867.

Nobel displayed an early aptitude for science and learning, particularly in chemistry and languages; he became fluent in six languages and filed his first patent at age 24. He embarked on many business ventures with his family, most notably owning Bofors, an iron and steel producer that he developed into a major manufacturer of cannons and other armaments.

Nobel was later inspired to donate his fortune to the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

institution, which would annually recognize those who "conferred the greatest benefit to humankind". The synthetic element nobelium was named after him, and his name and legacy also survives in companies such as Dynamit Nobel and AkzoNobel

Akzo Nobel N.V., stylized as AkzoNobel, is a Dutch multinational company which creates paints and performance coatings for both industry and consumers worldwide. Headquartered in Amsterdam, the company has activities in more than 80 countries, ...

, which descend from mergers with companies he founded.

Nobel was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for prom ...

, which, pursuant to his will, would be responsible for choosing the Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make ou ...

in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

and in chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

.

Personal life

Early life and education

Alfred Nobel was born inStockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

, United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two ...

on 21 October 1833. He was the third son of Immanuel Nobel (1801–1872), an inventor and engineer, and Karolina Andriette Nobel (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Ahlsell 1805–1889). The couple married in 1827 and had eight children. The family was impoverished and only Alfred and his three brothers survived beyond childhood.''Encyclopedia of Modern Europe: Europe 1789–1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire'', "Alfred Nobel", 2006 Thomson Gale. Through his father, Alfred Nobel was a descendant of the Swedish scientist Olaus Rudbeck (1630–1702), and in his turn, the boy was interested in engineering, particularly explosives, learning the basic principles from his father at a young age. Alfred Nobel's interest in technology was inherited from his father, an alumnus of Royal Institute of Technology

The KTH Royal Institute of Technology ( sv, Kungliga Tekniska högskolan, lit=Royal Institute of Technology), abbreviated KTH, is a public research university in Stockholm, Sweden. KTH conducts research and education in engineering and technolog ...

in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

. Following various business failures, Nobel's father moved to

Following various business failures, Nobel's father moved to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

and grew successful there as a manufacturer of machine tools and explosives. He invented the veneer lathe (which made possible the production of modern plywood) and started work on the torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, ...

. In 1842, the family joined him in the city. Now prosperous, his parents were able to send Nobel to private tutors and the boy excelled in his studies, particularly in chemistry and languages, achieving fluency in English, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Russian. For 18 months, from 1841 to 1842, Nobel went to the only school he ever attended as a child, in Stockholm.

Nobel gained proficiency in Swedish, French, Russian, English, German, and Italian. He also developed sufficient literary skill to write poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meani ...

in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

. His '' Nemesis'' is a prose tragedy in four acts about the Italian noblewoman Beatrice Cenci. It was printed while he was dying, but the entire stock was destroyed immediately after his death except for three copies, being regarded as scandalous and blasphemous. It was published in Sweden in 2003 and has been translated into Slovenian

Slovene or Slovenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Slovenia, a country in Central Europe

* Slovene language, a South Slavic language mainly spoken in Slovenia

* Slovenes, an ethno-linguistic group mainly living in Slovenia

* Sl ...

, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Italian, and Spanish.

Religion

Nobel wasLutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

and regularly attended the Church of Sweden Abroad during his Paris years, led by pastor Nathan Söderblom who received the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

in 1930. He became an agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficien ...

in youth and was an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

later in life, though still donated generously to the Church.

Health and relationships

Nobel travelled for much of his business life, maintaining companies in Europe and America while keeping a home in Paris from 1873 to 1891. He remained a solitary character, given to periods of depression. He remained unmarried, although his biographers note that he had at least three loves, the first in Russia with a girl named Alexandra who rejected his proposal. In 1876, Austro-Bohemian Countess Bertha Kinsky became his secretary, but she left him after a brief stay to marry her previous lover Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner. Her contact with Nobel was brief, yet she corresponded with him until his death in 1896, and probably influenced his decision to include a peace prize in his will. She was awarded the 1905 Nobel Peace prize "for her sincere peace activities". Nobel's longest-lasting relationship was with Sofija Hess fromCelje

)

, pushpin_map = Slovenia

, pushpin_label_position = left

, pushpin_map_caption = Location of the city of Celje in Slovenia

, coordinates =

, subdivision_type = Cou ...

whom he met in 1876. The liaison lasted for 18 years.

Residences

In the years of 1865 to 1873, Alfred Nobel had his home inKrümmel

Krümmel is an ''Ortsgemeinde'' – a community belonging to a ''Verbandsgemeinde'' – in the Westerwaldkreis in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. The community belongs to the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' of Selters, a kind of collective municipality.

Geo ...

, Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

, he afterward moved to a house in the Avenue Malakoff in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

that same year.

In 1894, when he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, the

In 1894, when he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, the Björkborn Manor

Björkborn Manor ( sv, Björkborns herrgård, ) is a manor house and the very last residence of Alfred Nobel in Sweden. The manor is located in Karlskoga Municipality, Örebro County, Sweden. The current-standing white-colored manor house was buil ...

was included, he stayed at his manor house in Sweden during the summers. The manor house became his very last residence in Sweden and has after his death functioned as a museum.

Alfred Nobel died on 10 December 1896, in Sanremo, Italy, at his very last residence, Villa Nobel

Villa Nobel is a historic villa situated in Sanremo, Italy.

History

The construction of the villa, built in 1871 and designed by architect Filippo Grossi, was commissioned by Rivoli pharmacist Pietro Vacchieri. On July 28, 1874, Vacchieri sold ...

, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

.

Scientific career

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin; then, in 1850, went toParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

to further the work. There he met Ascanio Sobrero

Ascanio Sobrero (12 October 1812 – 26 May 1888) was an Italian chemist, born in Casale Monferrato. He was studying under Théophile-Jules Pelouze at the University of Turin, who had worked with the explosive material guncotton.

He studied med ...

, who had invented nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

three years before. Sobrero strongly opposed the use of nitroglycerin because it was unpredictable, exploding when subjected to variable heat or pressure. But Nobel became interested in finding a way to control and use nitroglycerin as a commercially usable explosive; it had much more power than gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

. In 1851 at age 18, he went to the United States for one year to study, working for a short period under Swedish-American inventor John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive ''Novelty'', which co ...

, who designed the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

ironclad, USS ''Monitor''. Nobel filed his first patent, an English patent for a gas meter, in 1857, while his first Swedish patent, which he received in 1863, was on "ways to prepare gunpowder". The family factory produced

The family factory produced armaments

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

for the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

(1853–1856), but had difficulty switching back to regular domestic production when the fighting ended and they filed for bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debto ...

. In 1859, Nobel's father left his factory in the care of the second son, Ludvig Nobel

Ludvig Immanuel Nobel ( ; russian: Лю́двиг Эммануи́лович Нобе́ль, Ljúdvig Emmanuílovich Nobél’; sv, Ludvig Emmanuel Nobel ; 27 July 1831 – 12 April 1888) was a Swedish-Russian engineer, a noted businessman and a ...

(1831–1888), who greatly improved the business. Nobel and his parents returned to Sweden from Russia and Nobel devoted himself to the study of explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

, and especially to the safe manufacture and use of nitroglycerin. Nobel invented a detonator

A detonator, frequently a blasting cap, is a device used to trigger an explosive device. Detonators can be chemically, mechanically, or electrically initiated, the last two being the most common.

The commercial use of explosives uses electr ...

in 1863, and in 1865 designed the blasting cap

A detonator, frequently a blasting cap, is a device used to trigger an explosive device. Detonators can be chemically, mechanically, or electrically initiated, the last two being the most common.

The commercial use of explosives uses electri ...

.

On 3 September 1864, a shed used for preparation of nitroglycerin exploded at the factory in Heleneborg, Stockholm, Sweden, killing five people, including Nobel's younger brother Emil

Emil or Emile may refer to:

Literature

*''Emile, or On Education'' (1762), a treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

* ''Émile'' (novel) (1827), an autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

*''Emil and the Detective ...

. Fazed by the accident, Nobel founded the company Nitroglycerin Aktiebolaget AB in Vinterviken so that he could continue to work in a more isolated area. Nobel invented dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

in 1867, a substance easier and safer to handle than the more unstable nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

. Dynamite was patented in the US and the UK and was used extensively in mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the econom ...

and the building of transport networks internationally. In 1875, Nobel invented gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion- cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and saltp ...

, more stable and powerful than dynamite, and in 1887, patented ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented https://www.nobelprize.org/alfr ...

, a predecessor of cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in the United Kingdom since 1889 to replace black powder as a military propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burn ...

.

Nobel was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for prom ...

in 1884, the same institution that would later select laureates for two of the Nobel prizes, and he received an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

from Uppsala University

Uppsala University ( sv, Uppsala universitet) is a public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

The university rose to significance during ...

in 1893.

Nobel's brothers Ludvig and Robert founded the oil company Branobel

The Petroleum Production Company Nobel Brothers, Limited, or Branobel (short for братьев Нобель "brat'yev Nobel" — "Nobel Brothers" in Russian), was an oil company set up by Ludvig Nobel and Baron Peter von Bilderling. It operated ...

and became hugely rich in their own right. Nobel invested in these and amassed great wealth through the development of these new oil regions. During his life, Nobel was issued 355 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

s internationally, and by his death, his business had established more than 90 armaments factories, despite his apparently pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

character.

Inventions

Nobel found that whennitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

was incorporated in an absorbent inert substance like ''kieselguhr'' (diatomaceous earth

Diatomaceous earth (), diatomite (), or kieselgur/kieselguhr is a naturally occurring, soft, siliceous sedimentary rock that can be crumbled into a fine white to off-white powder. It has a particle size ranging from more than 3 μm to l ...

) it became safer and more convenient to handle, and this mixture he patented in 1867 as "dynamite". Nobel demonstrated his explosive for the first time that year, at a quarry in Redhill, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

, England. In order to help reestablish his name and improve the image of his business from the earlier controversies associated with dangerous explosives, Nobel had also considered naming the highly powerful substance "Nobel's Safety Powder", but settled with Dynamite instead, referring to the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

word for "power" ().

Nobel later combined nitroglycerin with various nitrocellulose compounds, similar to collodion

Collodion is a flammable, syrupy solution of nitrocellulose in ether and alcohol. There are two basic types: flexible and non-flexible. The flexible type is often used as a surgical dressing or to hold dressings in place. When painted on the skin, ...

, but settled on a more efficient recipe combining another nitrate explosive, and obtained a transparent, jelly-like substance, which was a more powerful explosive than dynamite. Gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion- cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and saltp ...

, or blasting gelatine, as it was named, was patented in 1876; and was followed by a host of similar combinations, modified by the addition of potassium nitrate and various other substances. Gelignite was more stable, transportable and conveniently formed to fit into bored holes, like those used in drilling and mining, than the previously used compounds. It was adopted as the standard technology for mining in the "Age of Engineering", bringing Nobel a great amount of financial success, though at a cost to his health. An offshoot of this research resulted in Nobel's invention of ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented https://www.nobelprize.org/alfr ...

, the precursor of many modern smokeless powder explosives and still used as a rocket propellant.

Nobel Prize

There is a well known story about the origin of the Nobel Prize, which seems to be an urban legend. In 1888, the death of his brother Ludvig supposedly caused several newspapers to publishobituaries

An obituary (obit for short) is an article about a recently deceased person. Newspapers often publish obituaries as news articles. Although obituaries tend to focus on positive aspects of the subject's life, this is not always the case. Acc ...

of Alfred in error. One French newspaper condemned him for his invention of military explosives—in many versions of the story, dynamite is quoted, although this was mainly used for civilian applications—and this is said to have brought about his decision to leave a better legacy after his death. The obituary stated, ' ("The merchant of death is dead"), and went on to say, "Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday." Nobel read the obituary and was appalled at the idea that he would be remembered in this way. His decision to posthumously donate the majority of his wealth to found the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

has been credited to him wanting to leave behind a better legacy. However, there appears to be no evidence that the obituary in question actually existed, suggesting that the whole story is false.

On 27 November 1895, at the Swedish- Norwegian Club in Paris, Nobel signed his last will and testament and set aside the bulk of his estate to establish the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

s, to be awarded annually without distinction of nationality. After taxes and bequests to individuals, Nobel's will allocated 94% of his total assets, 31,225,000 Swedish kronor, to establish the five Nobel Prizes. This converted to £1,687,837 (GBP) at the time. In 2012, the capital was worth around SEK 3.1 billion (US$472 million, EUR 337 million), which is almost twice the amount of the initial capital, taking inflation into account.

The first three of these prizes are awarded for eminence in physical science, in chemistry and in medical science or physiology; the fourth is for literary work "in an ideal direction" and the fifth prize is to be given to the person or society that renders the greatest service to the cause of international fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternit ...

, in the suppression or reduction of standing armies, or in the establishment or furtherance of peace congresses.

The formulation for the literary prize being given for a work "in an ideal direction" (' in Swedish), is cryptic and has caused much confusion. For many years, the Swedish Academy interpreted "ideal" as "idealistic" (') and used it as a reason not to give the prize to important but less romantic authors, such as Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential pla ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. This interpretation has since been revised, and the prize has been awarded to, for example, Dario Fo

Dario Luigi Angelo Fo (; 24 March 1926 – 13 October 2016) was an Italian playwright, actor, theatre director, stage designer, songwriter, political campaigner for the Italian left wing and the recipient of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Literature. ...

and José Saramago

José de Sousa Saramago, GColSE ComSE GColCa (; 16 November 1922 – 18 June 2010), was a Portuguese writer and recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Literature for his "parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony ith which hecon ...

, who do not belong to the camp of literary idealism.

There was room for interpretation by the bodies he had named for deciding on the physical sciences and chemistry prizes, given that he had not consulted them before making the will. In his one-page testament, he stipulated that the money go to discoveries or inventions in the physical sciences and to discoveries or improvements in chemistry. He had opened the door to technological awards, but had not left instructions on how to deal with the distinction between science and technology. Since the deciding bodies he had chosen were more concerned with the former, the prizes went to scientists more often than engineers, technicians or other inventors.

Sweden's central bank Sveriges Riksbank

Sveriges Riksbank, or simply the ''Riksbank'', is the central bank of Sweden. It is the world's oldest central bank and the fourth oldest bank in operation.

Etymology

The first part of the word ''riksbank'', ''riks'', stems from the Swedish w ...

celebrated its 300th anniversary in 1968 by donating a large sum of money to the Nobel Foundation to be used to set up a sixth prize in the field of economics in honour of Alfred Nobel. In 2001, Alfred Nobel's great-great-nephew, Peter Nobel (born 1931), asked the Bank of Sweden to differentiate its award to economists given "in Alfred Nobel's memory" from the five other awards. This request added to the controversy over whether the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel is actually a legitimate "Nobel Prize".

Death

Nobel was accused of high treason against France for selling

Nobel was accused of high treason against France for selling Ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented https://www.nobelprize.org/alfr ...

to Italy, so he moved from Paris to Sanremo, Italy in 1891. On 10 December 1896, he suffered a stroke and died. He had left most of his wealth in trust, unbeknownst to his family, in order to fund the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

awards. He is buried in Norra begravningsplatsen in Stockholm.

Monuments and legacy

The ''Monument to Alfred Nobel'' (, ) in Saint Petersburg is located along theBolshaya Nevka River

The Great Nevka or Bolshaya Nevka () is an arm of the Neva that begins about below the Liteyny Bridge in Saint Petersburg.

Attractions

* Bridges

** Samson Bridge

** Grenadiers Bridge

** Kantemirovsky Bridge

** Ushakovsky Bridge

** 3rd Yelagi ...

on Petrogradskaya Embankment. It was dedicated in 1991 to mark the 90th anniversary of the first Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

presentation. DiplomaThomas Bertelman

and Professor

Arkady Melua

Arkady Ivanovich Melua (7 February 1950, Kazatin) is the general director and editor-in-chief of the scientific publishing house, Humanistica.

Life and work

Starting in 1969, Melua served and worked as an engineer at the Ministry of Defense ...

were initiators of the creation of the monument (1989). Professor A. Melua has provided funds for the establishment of the monumentJ.S.Co. "Humanistica"

1990–1991). The abstract metal sculpture was designed by local artists Sergey Alipov and Pavel Shevchenko, and appears to be an explosion or branches of a tree. Petrogradskaya Embankment is the street where Nobel's family lived until 1859. Criticism of Nobel focuses on his leading role in weapons manufacturing and sales, and some question his motives in creating his prizes, suggesting they are intended to improve his reputation.

in '' The Local'' 4 October 2010

See also

*Nobel Foundation

The Nobel Foundation ( sv, Nobelstiftelsen) is a private institution founded on 29 June 1900 to manage the finances and administration of the Nobel Prizes. The foundation is based on the last will of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite.

I ...

References

Further reading

* Schück, H, and Sohlman, R., (1929). ''The Life of Alfred Nobel'', transl. Brian Lunn, London: William Heineman Ltd. * Alfred Nobel US Patent No 78,317, dated 26 May 1868 * Evlanoff, M. and Fluor, M. ''Alfred Nobel – The Loneliest Millionaire''. Los Angeles, Ward Ritchie Press, 1969. * Sohlman, R. ''The Legacy of Alfred Nobel'', transl. Schubert E. London: The Bodley Head, 1983 (Swedish original, ''Ett Testamente'', published in 1950). *External links

Alfred Nobel – Man behind the Prizes

Nobelprize.org

* ttp://azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/ai102_folder/102_articles/102_nobels_asbrink.html "The Nobels in Baku" in ''Azerbaijan International'', Vol 10.2 (Summer 2002), 56–59.

The Nobel Prize in Postage Stamps

* A German branch or followup ''(German)'' * *

Alfred Nobel and his unknown coworker

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nobel, Alfred 1833 births 1896 deaths Burials at Norra begravningsplatsen Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*'' Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interl ...

Nobel Prize

Engineers from Stockholm

19th-century Swedish businesspeople

19th-century Swedish scientists

19th-century Swedish engineers

Swedish chemists

Swedish philanthropists

Explosives engineers