Alexandra of Yugoslavia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexandra of Yugoslavia ( el, Αλεξάνδρα, sh-Cyrl-Latn, separator=/, Александра, Aleksandra; 25 March 1921 – 30 January 1993) was the last Queen of Yugoslavia as the wife of King Peter II.

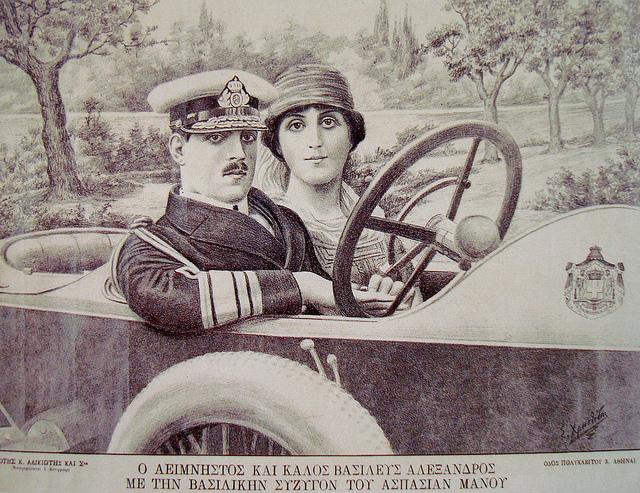

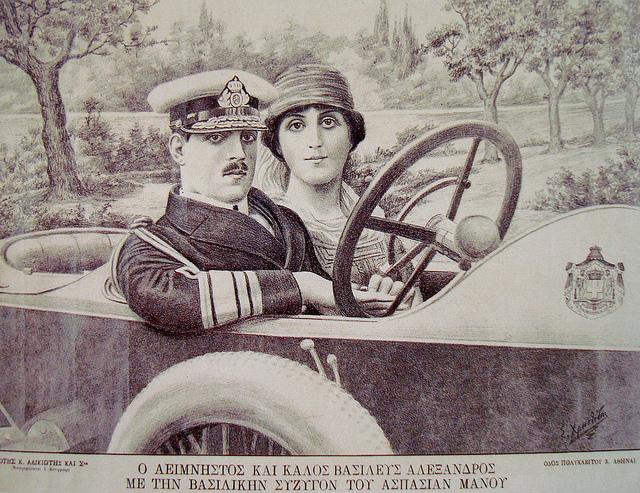

Posthumous daughter of King Alexander of Greece and his

Born Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, she was brought into a difficult environment. Five months before her birth, her father, King Alexander, died of

Born Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, she was brought into a difficult environment. Five months before her birth, her father, King Alexander, died of

Still, neither Alexandra nor Aspasia received more official recognition: from a legal point of view, they were commoners without any rights in the royal family. Things changed from July 1922 when, after the intervention of

Still, neither Alexandra nor Aspasia received more official recognition: from a legal point of view, they were commoners without any rights in the royal family. Things changed from July 1922 when, after the intervention of

In 1927, Alexandra and her mother moved to

In 1927, Alexandra and her mother moved to

/ref>

In this turbulent context, Alexandra gave birth to an heir, named

In this turbulent context, Alexandra gave birth to an heir, named

Now without income and any prospect of returning to Yugoslavia, Peter II and Alexandra resolved to leave Claridge's Hotel and moved to a mansion in the

Now without income and any prospect of returning to Yugoslavia, Peter II and Alexandra resolved to leave Claridge's Hotel and moved to a mansion in the

The couple reconciled and for a time they lived a second honeymoon. However, the need for money continued to be felt and Alexandra was persuaded by a British publisher to write her autobiography. With the help of the

The couple reconciled and for a time they lived a second honeymoon. However, the need for money continued to be felt and Alexandra was persuaded by a British publisher to write her autobiography. With the help of the

queen Alexandra wears the Star of Karađorđe on her right shoulder and star of the White Eagle on her right stomach * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the White Eagle (Serbia), Order of the White Eagle * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of theRoyal Family

/ref> * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Yugoslav Crown

The Royal FamilyThe Mausoleum of the Serbian Royal Family

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexandra Of Yugoslavia Greek princesses Danish princesses Yugoslav queens consort House of Glücksburg (Greece) Nobility from Athens 1921 births 1993 deaths Karađorđević dynasty Royal reburials Burials at the Mausoleum of the Royal House of Karađorđević, Oplenac People educated at Heathfield School, Ascot Greek emigrants to the United Kingdom Deaths from cancer in England Daughters of kings

morganatic

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spous ...

wife Aspasia Manos, Alexandra was not part of the Greek royal family until July 1922 when, at the behest of Queen Sophia, a law was passed which retroactively recognized marriages of members of the royal family, although on a non-dynastic basis; in consequence, she obtained the style and name of ''Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark''. At the same time, a serious political and military crisis, linked to the defeat of Greece by Turkey in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, led to the deposition and exile of the royal family, beginning in 1924. Being the only members of the dynasty allowed to remain in the country by the Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern historiographical term used to refer to the Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic Republic ( el, Ἑλ� ...

, the princess and her mother later found refuge in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, with Dowager Queen Sophia.

After three years with her paternal grandmother, Alexandra left Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

to continue her studies in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, while her mother settled in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. Separated from her mother, the princess fell ill, forcing Aspasia to make her leave the boarding school where she was studying. After the restoration of her uncle, King George II, on the Hellenic throne in 1935, Alexandra stayed in her native country several times but the outbreak of the Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War (Greek language, Greek: Ελληνοϊταλικός Πόλεμος, ''Ellinoïtalikós Pólemos''), also called the Italo-Greek War, Italian Campaign in Greece, and the War of '40 in Greece, took place between the kingdom ...

, in 1940, forced her and her mother to settle in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

. The invasion of Greece by the Axis powers in April–May 1941, however, led to their moving to the United Kingdom. Again exiled, Alexandra met in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

the young King Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II ( sr-Cyrl, Петар II Карађорђевић, Petar II Karađorđević; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last king of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until his deposition in November 1945. He was the last ...

, who also went into exile after the invasion of his country by the Germans.

Quickly, Alexandra and Peter II fell in love and planned to marry. Opposition from both Peter's mother, Maria, and the Yugoslav government in exile forced the couple to delay their marriage plans until 1944, when they finally celebrated their wedding. A year later, Alexandra gave birth to her only son, Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia

Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia ( sr, Александар Карађорђевић, Престолонаследник Југославије; born 17 July 1945 in London), is the head of the House of Karađorđević, the former royal h ...

. However, the happiness of the family was short-lived: on 29 November 1945, Marshal Tito

Tito may refer to:

People Mononyms

*Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980), commonly known mononymously as Tito, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman

*Roberto Arias (1918–1989), aka Tito, Panamanian international lawyer, diplomat, and journal ...

proclaimed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

and Alexandra, who had never set foot in her adopted country, was left without a crown. The abolition of the Yugoslav monarchy had very serious consequences for the royal couple. Penniless and unable to adapt to the role of citizen, Peter II turned to alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

and multiple affairs with other women. Depressed by the behavior of her husband, Alexandra neglected her son and made several suicide attempt

A suicide attempt is an attempt to die by suicide that results in survival. It may be referred to as a "failed" or "unsuccessful" suicide attempt, though these terms are discouraged by mental health professionals for implying that a suicide resu ...

s. After the death of Peter II in 1970, Alexandra's health continued to deteriorate. She died of cancer in 1993 and her remains were buried in the Royal Cemetery Plot in the park of Tatoi

Tatoi ( el, Τατόι, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Dekeleia. It is located from t ...

in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, before being transferred to the Royal Mausoleum of Oplenac

The St. George's Church in Oplenac ( sr-cyrl, Црква Светог Ђорђа на Опленцу, Crkva Svetog Đorđa na Oplencu), also known as Oplenac (Опленац), is the mausoleum of the Serbian and Yugoslav royal house of Karađorđ ...

in 2013.

Life

A birth surrounded by intrigues

The issue of the Greek succession

Born Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, she was brought into a difficult environment. Five months before her birth, her father, King Alexander, died of

Born Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, she was brought into a difficult environment. Five months before her birth, her father, King Alexander, died of sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

following a monkey bite which occurred in the gardens of Tatoi

Tatoi ( el, Τατόι, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Dekeleia. It is located from t ...

. The unexpected death of the sovereign caused a serious political crisis in Greece, at a time when public opinion was already divided by the events of the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the Greco-Turkish War. The King had concluded an unequal marriage with Aspasia Manos, and, in consequence, their offspring was not dynastic. Due to the lack of another candidate for the throne, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation move ...

was soon forced to accept the restoration of his enemy, King Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

, on 19 December 1920. Alexander's brief reign was officially treated as a regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, which meant that his marriage, contracted without his father's permission, was technically illegal, the marriage void, and the couple's posthumous child illegitimate.

The last months of pregnancy of Aspasia are surrounded by intrigue. In the case that she gave birth to a boy (who would be named Philip, as the father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

), rumours soon assured that she was determined to place him on the throne after his birth. True or not, this possibility worried the Greek royal family, whose fears about the birth of a male child were exploited by the Venizelists to revive the succession crisis. The birth of a girl, on 25 March 1921, was a great relief for the dynasty, and both King Constantine I and his mother, Queen Dowager Olga, agreed to be the godparents of the newborn.

Integration into the royal family

Still, neither Alexandra nor Aspasia received more official recognition: from a legal point of view, they were commoners without any rights in the royal family. Things changed from July 1922 when, after the intervention of

Still, neither Alexandra nor Aspasia received more official recognition: from a legal point of view, they were commoners without any rights in the royal family. Things changed from July 1922 when, after the intervention of Queen Sophia of Greece

Sophia of Prussia (Sophie Dorothea Ulrike Alice, el, Σοφία; 14 June 1870 – 13 January 1932) was Queen consort of the Hellenes from 1913–1917, and also from 1920–1922.

A member of the House of Hohenzollern and child of Frederick III, ...

, was passed a law which retroactively recognized marriages of members of the Royal Family, although on a non-dynastic basis; with this legal subterfuge, the little princess obtained the style of ''Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Monarchs and their consorts are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of address, spoken or written, it t ...

'' and the title of ''Princess of Greece and Denmark''. Thus, Alexandra's birth became legitimate in the eyes of Greek law, but since the marriage was recognized on a 'non-dynastic basis', her royal status was tenuous at best and she remained ineligible for the throne; however, this belated recognition made it possible for her to later make an advantageous marriage, which would not have been possible if she was nothing more than the daughter of the King's morganatic spouse.

Aspasia, however, was not mentioned in the law and remained a commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

in the eyes of protocol

Protocol may refer to:

Sociology and politics

* Protocol (politics), a formal agreement between nation states

* Protocol (diplomacy), the etiquette of diplomacy and affairs of state

* Etiquette, a code of personal behavior

Science and technology

...

. Humiliated by this difference in treatment, she begged Prince Christopher (whose commoner wife, Nancy Stewart Worthington Leeds

Princess Anastasia of Greece and Denmark (''née'' Nonie May Stewart; January 20, 1878 – August 29, 1923) was an American-born heiress and member of the Greek royal family. She was married to Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark, the younge ...

, was entitled to be known as a Princess of Greece and Denmark), to intercede on her behalf. Moved by the arguments of his niece-in-law, he approached Queen Sophia, who eventually changed her opinion. Under pressures from his wife, King Constantine I issued a decree, gazette

A gazette is an official journal, a newspaper of record, or simply a newspaper.

In English and French speaking countries, newspaper publishers have applied the name ''Gazette'' since the 17th century; today, numerous weekly and daily newspaper ...

d 10 September 1922 under which Aspasia received the title ''Princess of Greece and Denmark'' and the style of ''Royal Highness''.

Childhood in exile

From Athens to Florence

Despite these positive developments, the situation of Alexandra and her mother did not improve. Indeed, Greece experiencing a series of military defeats by Turkey and acoup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

soon forced King Constantine I to abdicate again, this time in favor of his eldest son, Crown Prince George, on 27 September 1922. Things went from bad to worse for the country; a further coup forced the new king, his wife and his brother to leave the country on 19 December 1923. On 25 March 1924, Alexandra's third birthday, the Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern historiographical term used to refer to the Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic Republic ( el, Ἑλ� ...

was proclaimed and both Aspasia and Alexandra were then the only members of the dynasty allowed to stay in Greece.

Penniless, Aspasia chose to take the path of exile with her daughter in early 1924. The two princesses found refuge with Queen Sophia, who had moved to the ''Villa Bobolina'' near Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, shortly after the death of her husband on 11 January 1923. The now dowager queen, who loved Alexandra, was thrilled, even if her financial situation was also precarious. With her paternal grandmother, the princess spent a happy childhood with her aunts Crown Princess Helen of Romania, Princesses Irene and Katherine of Greece, and her cousins Prince Philip of Greece (the future Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, was a substantive title that has been created three times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not prod ...

) and Prince Michael of Romania, who were her playmates during holidays.

From London to Venice

In 1927, Alexandra and her mother moved to

In 1927, Alexandra and her mother moved to Ascot, Berkshire

Ascot () is a town in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is south of Windsor, east of Bracknell and west of London. It is most notable as the location of Ascot Racecourse, home of the Royal Ascot meeting, ...

, in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

. They were greeted by Sir James Horlick, 4th Baronet, and his family, who harbored them in their Cowley Manor estate near the hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

. Now seven years old, Alexandra was enrolled in boarding schools in Westfield and Heathfield, as was the custom for the upper class. However, the Princess took very badly to this experience: separated from her mother, she stopped eating and eventually contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. Alarmed, Aspasia thus moved her daughter to Switzerland for treatment. Later, Alexandra was educated in a Parisian finishing school

A finishing school focuses on teaching young women social graces and upper-class cultural rites as a preparation for entry into society. The name reflects that it follows on from ordinary school and is intended to complete the education, wi ...

, during which time she and her mother stayed at the Hotel Crillon.

Eventually, the two princesses settled on the Island of Giudecca

Giudecca (; vec, Zueca) is an island in the Venetian Lagoon, in northern Italy. It is part of the '' sestiere'' of Dorsoduro and is a locality of the ''comune'' of Venice.

Geography

Giudecca lies immediately south of the central islands of Ve ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, where Aspasia acquired a small property with her savings and Horlick's financial support. The former home of Caroline Eden (1801-1854), daughter of Sir Frederick Eden, 2nd Baronet

Sir Frederick Morton Eden, 2nd Baronet, of Maryland (18 June 1766 – 14 November 1809) was an English writer on poverty and pioneering social investigator.

Early life

Frederick Morton Eden was the eldest son of Sir Robert Eden, 1st Baronet, of ...

, wife of Vice-Admiral Hyde Parker III and great-aunt of British Prime Minister Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

, the villa and its 3.6 hectares of landscaped grounds were nicknamed the Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden ( he, גַּן־עֵדֶן, ) or Garden of God (, and גַן־אֱלֹהִים ''gan- Elohim''), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2-3 and Ezekiel 28 ...

, which delighted the Greek Princesses.Jeff Cotton: ''The Garden of Eden''/ref>

Restoration of the Greek monarchy

Between Greece and Venice

In 1935, the Second Hellenic Republic was abolished and King George II (Alexandra's uncle) was restored to the throne after areferendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

organized by General Georgios Kondylis. Alexandra was then allowed to return to Greece, a country she had not seen since 1924. Although she continued to reside in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

with her mother (who still suffered the ostracism of the royal family), the princess was invited to all the great ceremonies that punctuate the life of the dynasty. In 1936, she participated in the official ceremonies which marked the reburial in Tatoi of the remains of King Constantine I, Queen Sophia, and Dowager Queen Olga; all three died in exile in Italy. Two years later, in 1938, she was invited to the wedding of her uncle, Crown Prince Paul, with Princess Frederica of Hanover.

Despite her participation in the ceremonies of the Greek royal family, at that time Alexandra understood that she was not a full member of the European royalty. Her mother had to claim in her name the share of the inheritance of Alexandra's paternal grandparents. Especially, the princess had to deal with the fact that her mother had no site in the royal necropolis of Tatoi. In fact, during the 1936 ceremonies, a chapel was arranged in the park of the palace for the remains of King Constantine I and Queen Sophia. The remains of King Alexander, previously based in the gardens next to his grandfather King George I, were then transferred at the side of his parents in the chapel, with no space reserved for Aspasia.

First marriage proposal

Now a teenager, Alexandra began to attract the gaze of men. In 1936, the fifteen-years-old Princess received her first marriage proposal: King Zog I of Albania, who wished to marry a member of the European royalty in order to consolidate his position, asked her hand. However, the Greek diplomacy, which maintained complex relations with the Kingdom of Albania because of the possession ofNorthern Epirus

sq, Epiri i Veriut rup, Epiru di Nsusu

, type = Part of the wider historic region of Epirus

, image_blank_emblem =

, blank_emblem_type =

, image_map = Epirus across Greece Albania4.svg

, map_caption ...

, rejected this proposal and King Zog I eventually married the Hungarian Countess Géraldine Apponyi de Nagy-Appony in 1938.

Like all women of her age, Alexandra attended numerous dances, which aimed to introduce her to the European elite. In 1937 she was presented in Paris, where she danced with her cousin, the Duke of Windsor

Duke of Windsor was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 8 March 1937 for the former monarch Edward VIII, following his abdication on 11 December 1936. The dukedom takes its name from the town where Windsor Castle, ...

, then residing in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

with his wife, the Duchess, after his abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

and subsequent marriage.

World War II

From Venice to London

The outbreak of theGreco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War (Greek language, Greek: Ελληνοϊταλικός Πόλεμος, ''Ellinoïtalikós Pólemos''), also called the Italo-Greek War, Italian Campaign in Greece, and the War of '40 in Greece, took place between the kingdom ...

on 28 October 1940 forced Alexandra and her mother suddenly to leave Venice and fascist Italy. They settled with the rest of the Royal Family in Athens. Eager to serve their country in this difficult moment, both Princesses became nurses alongside the other women of the Royal Family. However, after several months of victorious battles against the Italian forces, Greece was invaded by the army of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

on 6 April 1941. Alexandra and the majority of the members of the Royal Family left the country a few days later, on 22 April. After a brief stay in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, where they received a German bombing, the Greek Royal Family departed for Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

.

While several members of the Royal Family were forced to spend World War II in South Africa, Alexandra and her mother obtained the permission of King George II of Greece and the British government to move to the United Kingdom. They arrived at Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

in the autumn of 1941 and settled in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in the district of Mayfair

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London towards the eastern edge of Hyde Park, in the City of Westminster, between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane. It is one of the most expensive districts in the world ...

. In the British capital, the Greek princesses resumed their activities in the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

. Better accepted than in their own country, they were regular guests of the Duchess of Kent (born Princess Marina of Greece) and of the future Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, was a substantive title that has been created three times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not prod ...

(born Prince Philip of Greece), who was rumoured to be briefly engaged to Alexandra.

Love and marriage

However, it was not her cousin Philip whom Alexandra finally married. In 1942, the Princess met her third cousin, KingPeter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II ( sr-Cyrl, Петар II Карађорђевић, Petar II Karađorđević; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last king of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until his deposition in November 1945. He was the last ...

in an officers' gala at Grosvenor House. The 19-year-old sovereign had lived in exile in London since the invasion of his country by the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

on 6 April 1941. Quickly, they fell in love with each other and considered marriage, which greatly delighted Princess Aspasia. However, the sharp opposition of Queen Maria of Yugoslavia, Peter II's mother, and the Yugoslav government-in-exile, which deemed it indecent to celebrate a wedding while Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

was dismembered and occupied, prevented for a while the marital project. For two years, the lovers had only brief meetings in the residence of the Duchess of Kent.

After a brief stay of Peter II in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, the couple finally married on 20 March 1944. The ceremony, at which the King's mother refused to participate, was held at the Yugoslav embassy in London. Marked by restrictions due to the war, Alexandra wore a wedding dress that was lent her by Lady Mary Lygon, wife of Prince Vsevolod Ivanovich of Russia

Prince Vsevolod Ivanovich of Russia ( – 18 June 1973) was a male line great-great-grandson of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia and a nephew of King Alexander I of Yugoslavia. He was the last male member of the Romanov family born in Imperial Russia.Ki ...

(himself the son of King Peter's aunt Princess Helen of Serbia). Among the guests at the ceremony, there were four reigning monarchs (George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

, George II of Greece

George II ( el, Γεώργιος Βʹ, ''Geórgios II''; 19 July Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S.:_7_July.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S.:_7_July">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;"title="nowiki/ ...

, Haakon VII of Norway

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick V ...

and Wilhelmina of the Netherlands

Wilhelmina (; Wilhelmina Helena Pauline Maria; 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1890 until her abdication in 1948. She reigned for nearly 58 years, longer than any other Dutch monarch. Her reign saw World Wa ...

) and several other members of European royalty, including the two brothers of the groom ( Prince Tomislav and Prince Andrew), the mother of the bride, Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld

, house = Lippe

, father = Prince Bernhard of Lippe

, mother = Armgard von Cramm

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Count Bernhard of Biesterfeld

, birth_place = Jena, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Germany

, death_date = ...

Queen in exile

Liberation of Yugoslavia and the communist victory

Now queen of Yugoslavia, Alexandra, however, had tenuous links with her new country, living under the Nazi occupation. In 1941, a large portion of the Yugoslav territory was annexed by the Axis powers. Crown Prince Michael of Montenegro refused to resurrect his ancient Kingdom under Italian and German protection and guidance, and thus the region ofMontenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

had been transformed into a ''governorate'' by fascist Italy. Finally, the other two main parts of Yugoslavia were reduced to puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

s: the Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

of General Milan Nedić and the Croatian Kingdom of the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

. As all over occupied Europe, Yugoslav civilians suffered the abuses of the invaders and collaborators who supported them. Two groups emerged in the country: the Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav royali ...

, led by General monarchist Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Ar ...

, and the Partisans, led by the communist Marshal Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

.

From London, the Yugoslav government-in-exile supported the struggle of the royalist forces and appointed General Mihailović as Chief Minister of War. However, the importance of the Partisans pushed the allied forces to trust the Communists and give increasingly limited help to Mihailović, who was accused of collaborating with the Axis powers to shoot communist guerrillas. After the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

(1943), the Allies finally broke their ties with the Chetniks, forcing the Yugoslav government-in-exile to recognize the preeminence of the Partisans. In June 1944, Prime Minister Ivan Šubašić officially appointed Marshal Tito as the head of the Yugoslav resistance and Mihailović was dismissed. In October 1944, Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

and Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

concluded an agreement Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus, a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of law

** Meeting ...

to split Yugoslavia into two occupation zones, but after the liberation of Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

and the Partisans, it became clear the Communists predominated in the country. A harsh treatment, which affected the monarchists, took place; at the request of Churchill, Tito agreed in March 1945 to recognize a Regency Council (which had almost no activity) but opposed the return of King Peter II, who had to remain in exile with Alexandra while a government coalition dominated by the Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

was constituted in Belgrade.

Birth of Crown Prince Alexander and Peter II's deposition

In this turbulent context, Alexandra gave birth to an heir, named

In this turbulent context, Alexandra gave birth to an heir, named Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

after his two grandfathers, Alexander of Yugoslavia and Alexander of Greece. The birth took place in Suite 212 of Claridge's Hotel in Brook Street, London, on 17 July 1945. To enable the child to be born on Yugoslav soil, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill reportedly asked King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

to issue a decree transforming, for a day, Suite 212 into Yugoslav territory, which was to be the only time Alexandra was in Yugoslavia as queen. On 24 October 1945, the newborn Crown Prince was baptized by the Serbian Patriarch Gavrilo V in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, with King George VI and his elder daughter (the future Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

) acting as godparents.

The festivities marking the birth of the crown prince, however, were short-lived. Less than eight months after joining the coalition government, Milan Grol and Ivan Šubašić resigned their offices of Vice-Prime Minister (18 August) and Foreign Minister (8 October), respectively, to mark their political disagreement with Marshal Tito. Faced with the rise of the Communists, King Peter II decided, to withdraw his confidence from the Regency Council and regain all his sovereign prerogatives in Yugoslavia (8 August). Tito responded by immediately depriving the Royal Family of the civil list

A civil list is a list of individuals to whom money is paid by the government, typically for service to the state or as honorary pensions. It is a term especially associated with the United Kingdom and its former colonies of Canada, India, New Zeal ...

, which was soon to have dramatic consequences in the lives of the royal couple. Especially, Tito ordered the organization of early elections to a Constituent Assembly. The campaign took place in an irregular way, in the middle of pressures and violence of all kinds, with the opposition deciding to boycott the poll. On 24 November 1945 a single list presented by the communists was proposed to voters: while there were hardly more than 10,000 Communists throughout Yugoslavia before the war, their candidates list obtained more than 90% of the votes in the referendum.

In their first meeting on 29 November 1945, the Constituent Assembly voted immediately to abolish the monarchy and proclaimed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

. While no referendum accompanied this institutional change, the new regime was quickly recognized by virtually all of the international countries (except Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spani ...

).

Marital problems and suicide attempts

Financial and marital difficulties

Now without income and any prospect of returning to Yugoslavia, Peter II and Alexandra resolved to leave Claridge's Hotel and moved to a mansion in the

Now without income and any prospect of returning to Yugoslavia, Peter II and Alexandra resolved to leave Claridge's Hotel and moved to a mansion in the Borough of Runnymede

The Borough of Runnymede is a local government district with borough status in the English county of Surrey. It is a very prosperous part of the London commuter belt, with some of the most expensive housing in the United Kingdom outside cen ...

. Abandoned by the British government, they settled for a time in France, between Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

and Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo (; ; french: Monte-Carlo , or colloquially ''Monte-Carl'' ; lij, Munte Carlu ; ) is officially an administrative area of the Principality of Monaco, specifically the ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugues, where the Monte Carlo Casino is ...

, then in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

at St. Moritz. Increasingly penniless, they ended up leaving Europe and in 1949, they settled in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where the former King hoped to complete a financial project. Still penniless, the couple was forced to sell Alexandra's necklace of emeralds and other pieces of her jewelry to pay their accumulated debts. In addition to these difficulties was the fact that they were unable to manage a budget. As Alexandra wrote in her autobiography, she had no idea of the value of things, and she quickly proved incapable of maintaining a home.

In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, Peter II soon drifted away. Having made poor financial investments, he lost the little money he had left. Unable to adapt to the daily life of a normal citizen, he turned to alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

and affairs with younger women. For her part, Alexandra's love for her husband turned to obsession. Likely prone to anorexia

Anorexia nervosa, often referred to simply as anorexia, is an eating disorder characterized by low weight, food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin. ''Anorexia'' is a term of Gre ...

for years, increasingly unstable, she made her first suicide attempt

A suicide attempt is an attempt to die by suicide that results in survival. It may be referred to as a "failed" or "unsuccessful" suicide attempt, though these terms are discouraged by mental health professionals for implying that a suicide resu ...

during a visit to her mother in Venice during the summer of 1950.

The relations of the royal couple went from bad to worse. Alexandra used her son to put pressure on her husband and the child witnessed very violent scenes between his parents. Thanks to the intervention of his maternal grandmother, the 4-year-old former Crown Prince Alexander was sent to Italy with the Count and Countess of Robilant, friends of the royal couple. The child then grew up in an atmosphere much more stable and loving, with only a few visits from his parents.Divorce attempt and reconciliation

The year 1952 was marked by further financial problems due to bad investments of Peter II. Alexandra also suffered a miscarriage. The couple returned to France, where the situation did not improve. In 1953, Alexandra made another suicide attempt inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, which she survived thanks to a phone call from her aunt, Queen Frederica of Greece. Tired by the mental instability of his wife, Peter II finally launched a process of divorce in the French courts. The intervention of his son the crown prince and the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

and queen of Greece convinced him, however, to abandon his intentions.

The couple reconciled and for a time they lived a second honeymoon. However, the need for money continued to be felt and Alexandra was persuaded by a British publisher to write her autobiography. With the help of the

The couple reconciled and for a time they lived a second honeymoon. However, the need for money continued to be felt and Alexandra was persuaded by a British publisher to write her autobiography. With the help of the ghostwriter

A ghostwriter is hired to write literary or journalistic works, speeches, or other texts that are officially credited to another person as the author. Celebrities, executives, participants in timely news stories, and political leaders often ...

Joan Reeder, in 1956 she published ''For Love of a King'' (translated into French the following year under the title ''Pour l'Amour d'un Roi''). Alexandra was always in financial need despite the relative success of the book. In 1959, she co-wrote a second book, this time about her cousin, the Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, was a substantive title that has been created three times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not prod ...

. Though it revealed nothing compromising about the Duke of Edinburgh, the book prompted the British Royal Family to distance itself from Alexandra.

For some time, the couple moved to Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. The ...

, while Peter II maintained a chancellery in Monte Carlo. Considering himself still King of Yugoslavia, the former sovereign continued to award titles and decorations. Supported by some monarchists as the "Duke of Saint-Bar", he even maintained an embassy in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

. However, the reconciliation of the royal couple finally soured and Peter II returned to live in the United States while Alexandra moved with her mother to the Garden of Eden.

In 1963, on 1 September or before, Alexandra made another suicide attempt in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. Narrowly saved by her son former Crown Prince Alexander, she spent a long period of convalescence under the constant care of her sister-in-law, Princess Margarita of Baden (wife of Peter II's brother Prince Tomislav of Yugoslavia). Once recovered, Alexandra reconciled again with Peter II and the couple returned to live in the French capital in 1967. But, as before, the reconciliation was temporary and soon Peter II returned to live permanently in the United States while Alexandra settled in her mother's residence.

Last years

Peter II died on 3 November 1970 inDenver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, United States, during an attempted liver transplant. Lacking resources, his remains were buried in Saint Sava Monastery Church at Libertyville, Illinois

Libertyville is a village in Lake County, Illinois, United States, and a northern suburb of Chicago. It is located west of Lake Michigan on the Des Plaines River. The 2020 census population was 20,579. It is part of Libertyville Township, whi ...

, making him the only European monarch so far to have been buried in America. Still unstable and impoverished, Alexandra did not attend the ceremony, which took place in relative privacy.

Two years later, on 1 July 1972, former Crown Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia (now Head of the House of Karađorđević), married at Villamanrique de la Condesa, near Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Princess Maria da Glória of Orléans-Braganza, daughter of Brazilian Imperial pretender Prince Pedro Gastão of Orléans-Braganza and first cousin of King Juan Carlos I of Spain

Juan Carlos I (;,

* ca, Joan Carles I,

* gl, Xoán Carlos I, Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 Novem ...

. Too fragile emotionally, Alexandra did not attend the wedding of her son and it was her father's cousin Princess Olga of Greece (wife of Prince-Regent Paul of Yugoslavia), who escorted the groom to the altar.

One month later, on 7 August 1972, Alexandra's mother Princess Aspasia died. Now alone, she finally sold the Garden of Eden in 1979 and returned to the United Kingdom because of her health problems. She died of cancer at Burgess Hill

Burgess Hill is a town and civil parish in West Sussex, England, close to the border with East Sussex, on the edge of the South Downs National Park, south of London, north of Brighton and Hove, and northeast of the county town, Chichester. It ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ...

, on 30 January 1993.

The funeral of Alexandra was held in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, in the presence of her son, her three grandsons (Hereditary Prince Peter, Prince Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who populariz ...

and Prince Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

) and several members of the Greek royal family, including the former King Constantine II and Queen Anne-Marie

Anne-Marie Rose Nicholson (born 7 April 1991) is an English singer. She has attained charting singles on the UK Singles Chart, including Clean Bandit's " Rockabye", which peaked at number one, as well as "Alarm", " Ciao Adios", "Friends", "200 ...

. Alexandra's remains were then buried in the Royal cemetery park at Tatoi

Tatoi ( el, Τατόι, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Dekeleia. It is located from t ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, next to her mother.

On 26 May 2013, Alexandra's remains were transferred to Serbia for reburial in the crypt of the Royal Mausoleum at Oplenac

The St. George's Church in Oplenac ( sr-cyrl, Црква Светог Ђорђа на Опленцу, Crkva Svetog Đorđa na Oplencu), also known as Oplenac (Опленац), is the mausoleum of the Serbian and Yugoslav royal house of Karađorđ ...

. With her, the remains of her husband King Peter II, her mother-in-law Queen Mother Maria and brother-in-law Prince Andrew were also reburied at the same time in an official ceremony which was attended by Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić

Tomislav Nikolić ( sr-Cyrl, Томислав Николић, ; born 15 February 1952) is a Serbian retired politician who served as the president of Serbia from 2012 to 2017. A former member of the far-right Serbian Radical Party (SRS), he di ...

and his government.

Honours

* Greek Royal Family: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Olga and Sophia * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Karađorđequeen Alexandra wears the Star of Karađorđe on her right shoulder and star of the White Eagle on her right stomach * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the White Eagle (Serbia), Order of the White Eagle * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of the

Order of St. Sava

The Royal Order of St. Sava is an Order of merit, first awarded by the Kingdom of Serbia in 1883 and later by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It was awarded to nationals and foreigners for meritorious ach ...

/ref> * House of Karađorđević: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Yugoslav Crown

Ancestry

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * *External links

The Royal Family

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexandra Of Yugoslavia Greek princesses Danish princesses Yugoslav queens consort House of Glücksburg (Greece) Nobility from Athens 1921 births 1993 deaths Karađorđević dynasty Royal reburials Burials at the Mausoleum of the Royal House of Karađorđević, Oplenac People educated at Heathfield School, Ascot Greek emigrants to the United Kingdom Deaths from cancer in England Daughters of kings