Alexander Agassiz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

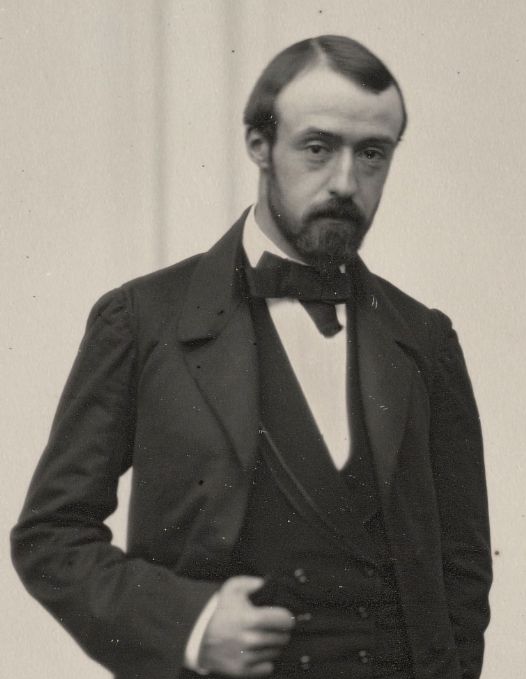

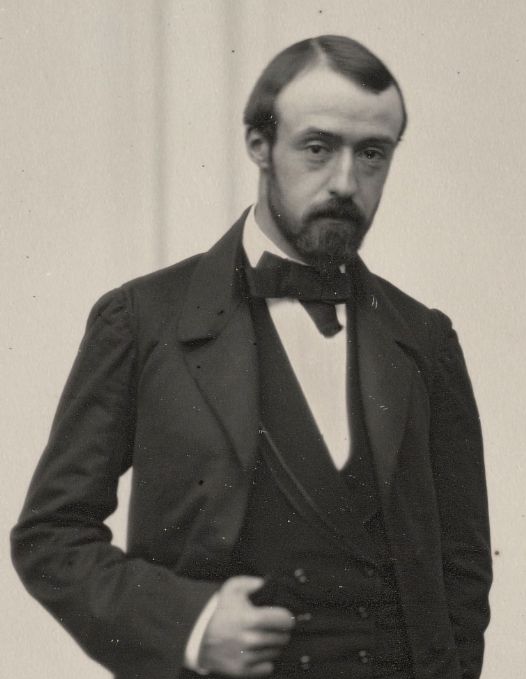

Alexander Emmanuel Rodolphe Agassiz (December 17, 1835March 27, 1910), son of

E. J. Hulbert, a friend of Agassiz's brother-in-law,

E. J. Hulbert, a friend of Agassiz's brother-in-law,  Shortly after the death of his father in 1873, Agassiz acquired a small peninsula in

Shortly after the death of his father in 1873, Agassiz acquired a small peninsula in

"List of the echinoderms sent to different institutions in exchange for other specimens, with annotations".

''Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 1 (2): 17–28. *Agassiz, Elizabeth C., and Alexander Agassiz (1865)

''Seaside Studies in Natural History.''

Boston: Ticknor and Fields. *Agassiz, Alexander (1872–1874)

"Illustrated Catalogue of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, at Harvard College. No. VII. Revision of the Echini. Parts 1–4".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 3: 1–762

Plates

*Agassiz, Alexander (1877)

"North American starfishes".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 5 (1): 1–136. *Agassiz, Alexander (1881)

''Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873–76. Zoology.'' 9: 1–321. *Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"Three cruises of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey steamer 'Blake' in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the Atlantic coast of the United States, from 1877 to 1880. Vol I".

''Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 14: 1–314. *Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"Three cruises of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey steamer 'Blake' in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the Atlantic coast of the United States, from 1877 to 1880. Vol II".

''Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 15: 1–220. *Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"The coral reefs of the tropical Pacific".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 28: 1–410

Plates I.Plates II.Plates III.

*Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"The coral reefs of the Maldives".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 29: 1–168. *Agassiz, Alexander (1904)

"The Panamic deep sea Echini".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 31: 1–243

Plates.

Letters and Recollections of Alexander Agassiz with a sketch of his life and work

Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co. * * Murray, John (1911).

Alexander Agassiz: His Life and Scientific Work

Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology

54 (3). pp 139–158. * * *

Publications by and about Alexander Agassiz

in the catalogue Helveticat of the

National Mining Hall of Fame: ''Alexander Agassiz''

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

Preserving many significant buildings and an archives of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company and Alexander Agassiz. {{DEFAULTSORT:Agassiz, Alexander 1835 births 1910 deaths 19th-century American zoologists 20th-century American zoologists American curators American ichthyologists Agassiz family Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Victoria Medal recipients Calumet and Hecla Mining Company personnel United States Coast Survey personnel Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni Swiss emigrants to the United States People from Neuchâtel People who died at sea Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

and stepson of Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz, was an American scientist and engineer.

Biography

Agassiz was born inNeuchâtel

, neighboring_municipalities= Auvernier, Boudry, Chabrey (VD), Colombier, Cressier, Cudrefin (VD), Delley-Portalban (FR), Enges, Fenin-Vilars-Saules, Hauterive, Saint-Blaise, Savagnier

, twintowns = Aarau (Switzerland), Besançon (Fra ...

, Switzerland and immigrated to the United States with his parents, Louis and Cecile (Braun) Agassiz, in 1846. He graduated from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

in 1855, subsequently studying engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

and chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

, and taking the degree of Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

at the Lawrence Scientific School

The Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) is the engineering school within Harvard University's Faculty of Arts and Sciences, offering degrees in engineering and applied sciences to graduate students admitted ...

of the same institution in 1857; in 1859 became an assistant in the United States Coast Survey

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

.

Thenceforward he became a specialist in marine ichthyology

Ichthyology is the branch of zoology devoted to the study of fish, including bony fish ( Osteichthyes), cartilaginous fish ( Chondrichthyes), and jawless fish ( Agnatha). According to FishBase, 33,400 species of fish had been described as of Oct ...

. Agassiz was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1862. Up until the summer of 1866, Agassiz worked as assistant curator in the museum of natural history that his father founded at Harvard.

E. J. Hulbert, a friend of Agassiz's brother-in-law,

E. J. Hulbert, a friend of Agassiz's brother-in-law, Quincy Adams Shaw

Quincy Adams Shaw (February 8, 1825June 12, 1908) was a Boston Brahmin investor and business magnate who was the first president of Calumet and Hecla Mining Company.

Family and early life

Shaw came from a famous and moneyed Boston family. With ...

, had discovered a rich copper lode known as the Calumet conglomerate on the Keweenaw Peninsula

The Keweenaw Peninsula ( , sometimes locally ) is the northernmost part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. It projects into Lake Superior and was the site of the first copper boom in the United States, leading to its moniker of " Copper Country." A ...

in Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and t ...

. Hulbert persuaded them, along with a group of friends, to purchase a controlling interest in the mines, which later became known as the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company

The Calumet and Hecla Mining Company was a major copper-mining company based within Michigan's Copper Country. In the 19th century, the company paid out more than $72 million in shareholder dividends, more than any other mining company in the Un ...

based in Calumet, Michigan

Calumet ( or ) is a village in Calumet Township, Houghton County, in the U.S. state of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, that was once at the center of the mining industry of the Upper Peninsula. Also known as Red Jacket, the village includes the ...

. That summer, he took a trip to see the mines for himself and he afterwards became treasurer of the enterprise.

Over the winter of 1866 and early 1867, mining operations began to falter, due to the difficulty of extracting copper from the conglomerate. Hulbert had sold his interests in the mines and had moved on to other ventures. But Agassiz refused to give up hope for the mines. He returned to the mines in March 1867, with his wife and young son. At that time, Calumet was a remote settlement, virtually inaccessible during the winter and very far removed from civilization even during the summer. With insufficient supplies at the mines, Agassiz struggled to maintain order, while back in Boston, Shaw was saddled with debt and the collapse of their interests. Shaw obtained financial assistance from John Simpkins, the selling agent for the enterprise to continue operations.

Agassiz continued to live at Calumet, making gradual progress in stabilizing the mining operations, such that he was able to leave the mines under the control of a general manager and return to Boston in 1868 before winter closed navigation. The mines continued to prosper and in May 1871, several mines were consolidated to form the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company

The Calumet and Hecla Mining Company was a major copper-mining company based within Michigan's Copper Country. In the 19th century, the company paid out more than $72 million in shareholder dividends, more than any other mining company in the Un ...

with Shaw as its first president. In August 1871, Shaw "retired" to the board of directors and Agassiz became president, a position he held until his death. Until the turn of the century, this company was by far the largest copper producer in the United States, many years producing over half of the total.

Agassiz was a major factor in the mine's continued success and visited the mines twice a year. He innovated by installing a giant engine, known as the Superior, which was able to lift 24 tons of rock from a depth of . He also built a railroad and dredged a channel to navigable waters. However, after a time the mines did not require his full-time, year-round, attention and he returned to his interests in natural history at Harvard. Out of his copper fortune, he gave some US$500,000 to Harvard for the museum of comparative zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

and other purposes.

Shortly after the death of his father in 1873, Agassiz acquired a small peninsula in

Shortly after the death of his father in 1873, Agassiz acquired a small peninsula in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, which features views of Narragansett Bay. Here he built a substantial house and a laboratory for use as his summer residence. The house was completed in 1875 and today is known as the Inn at Castle Hill.

He was a member of the scientific-expedition to South America in 1875, where he inspected the copper mines of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

, and made extended surveys of Lake Titicaca

Lake Titicaca (; es, Lago Titicaca ; qu, Titiqaqa Qucha) is a large freshwater lake in the Andes mountains on the border of Bolivia and Peru. It is often called the highest navigable lake in the world. By volume of water and by surface area, i ...

, besides collecting invaluable Peruvian antiquities, which he gave to the Museum of Comparative Zoology

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make thes ...

(MCZ), of which he was first curator from 1874 to 1885 and then director until his death in 1910, his personal secretary Elizabeth Hodges Clark running the day-to-day management of the MCZ when his work took him abroad. He assisted Charles Wyville Thomson

Sir Charles Wyville Thomson (5 March 1830 – 10 March 1882) was a Scottish natural historian and marine zoologist. He served as the chief scientist on the Challenger expedition; his work there revolutionized oceanography and led to his knigh ...

in the examination and classification of the collections of the 1872 ''Challenger'' Expedition, and wrote the ''Review of the Echini'' (2 vols., 1872–1874) in the reports. Between 1877 and 1880 he took part in the three dredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing d ...

expeditions of the steamer ''Blake'' of the Coast Survey, and presented a full account of them in two volumes (1888). Also in 1875, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

In 1896 Agassiz visited Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

and Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

and inspected the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, A ...

, publishing a paper on the subject in 1898.

Of Agassiz's other writings on marine zoology, most are contained in the bulletins and memoirs of the museum of comparative zoology. However, in 1865, he published with Elizabeth Cary Agassiz

Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz (pseudonym, Actaea; December 5, 1822 – June 27, 1907) was an American educator, naturalist, writer, and the co-founder and first president of Radcliffe College. A researcher of natural history, she was an author and ...

, his stepmother, ''Seaside Studies in Natural History'', a work at once exact and stimulating. They also published, in 1871, ''Marine Animals of Massachusetts Bay''.

He received the German Order Pour le Mérite

The ' (; , ) is an order of merit (german: Verdienstorden) established in 1740 by King Frederick II of Prussia. The was awarded as both a military and civil honour and ranked, along with the Order of the Black Eagle, the Order of the Red Eag ...

for Science and Arts in August 1902.

Agassiz served as a president of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

, which since 1913 has awarded the Alexander Agassiz Medal

The Alexander Agassiz Medal is awarded every three years by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences for an original contribution in the science of oceanography. It was established in 1911 by Sir John Murray in honor of his friend, the scientist Ale ...

in his memory. He died in 1910 on board the RMS ''Adriatic'' en route to New York from Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

.

He and his wife Anna Russell (1840-1873) were the parents of three sons – George Russell Agassiz (1861–1951), Maximilian Agassiz (1866–1943) and Rodolphe Louis Agassiz (1871–1933).

Legacy

Alexander Agassiz is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of lizard, ''Anolis agassizi

Agassiz's anole (''Anolis agassizi'') is a species of lizard in the family Dactyloidae. The species is endemic to Malpelo Island, which is part of Colombia.

Etymology

The specific name, ''agassizi'', is in honour of Alexander Agassiz, who w ...

'', and a fish, '' Leptochilichthys agassizii''.

A statue of Alexander Agassiz erected in 1923 is located in Calumet, Michigan, next to his summer home where he stayed while fulfilling his duties as the President of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company. The Company Headquarters, Agassiz' statue, and many other buildings and landmarks from the now defunct company are today administered and maintained by the Keweenaw National Historical Park

Keweenaw National Historical Park is a unit of the U.S. National Park Service. Established in 1992, the park celebrates the life and history of the Keweenaw Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan. As of 2009, it is a pa ...

, whose headquarters overlook the statue of Agassiz.

Publications

*Agassiz, Alexander (1863)"List of the echinoderms sent to different institutions in exchange for other specimens, with annotations".

''Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 1 (2): 17–28. *Agassiz, Elizabeth C., and Alexander Agassiz (1865)

''Seaside Studies in Natural History.''

Boston: Ticknor and Fields. *Agassiz, Alexander (1872–1874)

"Illustrated Catalogue of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, at Harvard College. No. VII. Revision of the Echini. Parts 1–4".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 3: 1–762

Plates

*Agassiz, Alexander (1877)

"North American starfishes".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 5 (1): 1–136. *Agassiz, Alexander (1881)

''Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873–76. Zoology.'' 9: 1–321. *Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"Three cruises of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey steamer 'Blake' in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the Atlantic coast of the United States, from 1877 to 1880. Vol I".

''Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 14: 1–314. *Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"Three cruises of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey steamer 'Blake' in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the Atlantic coast of the United States, from 1877 to 1880. Vol II".

''Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 15: 1–220. *Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"The coral reefs of the tropical Pacific".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 28: 1–410

Plates I.

*Agassiz, Alexander (1903)

"The coral reefs of the Maldives".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 29: 1–168. *Agassiz, Alexander (1904)

"The Panamic deep sea Echini".

''Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology'' 31: 1–243

Plates.

See also

*Agassiz family

The Agassiz Family is a family of Swiss origin, from the small village of Agiez near Lake Neuchatel. The family has included a number of high-profile members, such as the scientists Louis and Alexander Agassiz, as well as the founder of the Longi ...

References

External links

* Agassiz, George (1913)Letters and Recollections of Alexander Agassiz with a sketch of his life and work

Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co. * * Murray, John (1911).

Alexander Agassiz: His Life and Scientific Work

Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology

54 (3). pp 139–158. * * *

Publications by and about Alexander Agassiz

in the catalogue Helveticat of the

Swiss National Library

The Swiss National Library (german: Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek, french: Bibliothèque nationale suisse, it, Biblioteca nazionale svizzera, rm, Biblioteca naziunala svizra) is the national library of Switzerland. Part of the Federal Office ...

National Mining Hall of Fame: ''Alexander Agassiz''

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

Preserving many significant buildings and an archives of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company and Alexander Agassiz. {{DEFAULTSORT:Agassiz, Alexander 1835 births 1910 deaths 19th-century American zoologists 20th-century American zoologists American curators American ichthyologists Agassiz family Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Victoria Medal recipients Calumet and Hecla Mining Company personnel United States Coast Survey personnel Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni Swiss emigrants to the United States People from Neuchâtel People who died at sea Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala