Albrecht von Haller on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Albrecht von Haller (also known as Albertus de Haller; 16 October 170812 December 1777) was a Swiss

Albrecht von Haller (also known as Albertus de Haller; 16 October 170812 December 1777) was a Swiss

Haller's attention had been directed to the profession of medicine while he was residing in the house of a physician at

Haller's attention had been directed to the profession of medicine while he was residing in the house of a physician at

Haller then visited

Haller then visited

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf * * ''Deux Memoires sur le mouvement du sang et sur les effets de la saignée: fondés sur des experiences faites sur des animaux'' 175

* ** * ''Historia stirpium indigenarum Helvetiae inchoata.'' Bernae, 1768. Vol. 1&

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf. * * * * ** * ''Ode sur les Alpes'', 1773 * ''Materia medica oder Geschichte der Arzneyen des Pflanzenreichs''. Vol. 1&2. Leipzig: Haug, 1782

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf. * ''Histoire des Plantes suisses ou Matiere médicale et de l'Usage économique des Plantes par M. Alb. de Haller ... Traduit du Latin''. Vol. 1&2. Berne 179

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf. * * * *

Albrecht von Haller (also known as Albertus de Haller; 16 October 170812 December 1777) was a Swiss

Albrecht von Haller (also known as Albertus de Haller; 16 October 170812 December 1777) was a Swiss anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

, physiologist, naturalist, encyclopedist, bibliographer

Bibliography (from and ), as a discipline, is traditionally the academic study of books as physical, cultural objects; in this sense, it is also known as bibliology (from ). English author and bibliographer John Carter describes ''bibliography ...

and poet. A pupil of Herman Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave (, 31 December 1668 – 23 September 1738Underwood, E. Ashworth. "Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years." ''The British Medical Journal'' 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20395297.) was a Dutch botanist, ...

, he is often referred to as "the father of modern physiology."

Early life

Haller was born into an old Swiss family at Bern. Prevented by long-continued ill-health from taking part in boyish sports, he had more opportunity for the development of his precocious mind. At the age of four, it is said, he used to read and expound theBible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

to his father's servants; before he was ten he had sketched a Biblical Aramaic

Biblical Aramaic is the form of Aramaic that is used in the books of Daniel and Ezra in the Hebrew Bible. It should not be confused with the Targums – Aramaic paraphrases, explanations and expansions of the Hebrew scriptures.

History

During ...

grammar, prepared a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

vocabulary, compiled a collection of two thousand biographies of famous men and women on the model of the great works of Bayle and Moréri, and written in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

verse a satire on his tutor, who had warned him against a too great excursiveness. When still hardly fifteen he was already the author of numerous metrical translations from Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

, Horace and Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, as well as of original lyrics, dramas, and an epic of four thousand lines on the origin of the Swiss confederations, writings which he is said on one occasion to have rescued from a fire at the risk of his life, only, however, to burn them a little later (1729) with his own hand.

Medicine

Biel

, french: Biennois(e)

, neighboring_municipalities= Brügg, Ipsach, Leubringen/Magglingen (''Evilard/Macolin''), Nidau, Orpund, Orvin, Pieterlen, Port, Safnern, Tüscherz-Alfermée, Vauffelin

, twintowns = Iserlohn (Germany) ...

after his father's death in 1721. While still a sickly and excessively shy youth, he went in his sixteenth year to the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (german: Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen; la, Universitas Eberhardina Carolina), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-W� ...

(December 1723), where he studied under Elias Rudolph Camerarius Jr. and Johann Duvernoy. Dissatisfied with his progress, he in 1725 exchanged Tübingen for Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wi ...

, where Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave (, 31 December 1668 – 23 September 1738Underwood, E. Ashworth. "Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years." ''The British Medical Journal'' 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20395297.) was a Dutch botanist, ...

was in the zenith of his fame, and where Albinus had already begun to lecture in anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

. At that university he graduated in May 1727, undertaking successfully in his thesis to prove that the so-called salivary

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary glan ...

duct, claimed as a recent discovery by Georg Daniel Coschwitz (1679–1729), was nothing more than a blood-vessel.

"Sensibility" and "irritability"

In 1752, at the University of Göttingen, Haller published his thesis (''De partibus corporis humani sensibilibus et irritabilibus'') discussing the distinction between "sensibility" and "irritability" in organs, suggesting that nerves were "sensible" because of a person's ability to perceive contact while muscles were "irritable" because the fiber could measurably shorten on its own, regardless of a person's perception, when excited by a foreign body."Nerve impulses" vs. "muscular contractions"

Later in 1757, he conducted a famous series of experiments to distinguish between nerve impulses and muscular contractions.Other disciplines

Haller then visited

Haller then visited London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, making the acquaintance of Sir Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector, with a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Mu ...

, William Cheselden, John Pringle John Pringle may refer to:

*John Pringle, Lord Haining (c. 1674–1754), Scottish landowner, judge and politician, shire commissioner for Selkirk 1702–07, MP for Selkirkshire 1708–29, Lord of Session

*Sir John Pringle, 1st Baronet (1707–1782) ...

, James Douglas and other scientific men; next, after a short stay in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, he visited Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, where he studied under Henri François Le Dran and Jacob Winslow; and in 1728 he proceeded to Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, where he devoted himself to the study of higher mathematics under John Bernoulli. It was during his stay there also that his interest in botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

was awakened; and, in the course of a tour (July/August, 1728), through Savoy, Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden i ...

and several of the cantons of Switzerland

The 26 cantons of Switzerland (german: Kanton; french: canton ; it, cantone; Sursilvan and Surmiran: ; Vallader and Puter: ; Sutsilvan: ; Rumantsch Grischun: ) are the member states of the Swiss Confederation. The nucleus of the Swiss Co ...

, he began a collection of plants which was afterwards the basis of his great work on the flora of Switzerland. From a literary point of view the main result of this, the first of his many journeys through the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

, was his poem entitled ''Die Alpen'', which was finished in March 1729, and appeared in the first edition (1732) of his ''Gedichte''. This poem of 490 hexameters is historically important as one of the earliest signs of the awakening appreciation of the mountains, though it is chiefly designed to contrast the simple and idyllic life of the inhabitants of the Alps with the corrupt and decadent existence of the dwellers in the plains.

In 1729 he returned to Bern and began to practice as a physician; his best energies, however, were devoted to the botanical and anatomical researches which rapidly gave him a European reputation, and procured for him from George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

in 1736 a call to the chair of medicine, anatomy, botany and surgery in the newly founded University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

in 1743, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1747, and was ennobled in 1749.

The quantity of work achieved by Haller in the seventeen years during which he occupied his Göttingen professorship was immense. Apart from the ordinary work of his classes, which entailed the task of newly organizing a botanical garden (now the Old Botanical Garden of Göttingen University), an anatomical theatre and museum, an obstetrical school, and similar institutions, he carried on without interruption original investigations in botany and physiology, the results of which are preserved in the numerous works associated with his name. He also continued to persevere in his youthful habit of poetical composition, while at the same time he conducted a monthly journal (the ''Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen''), to which he is said to have contributed twelve thousand articles relating to almost every branch of human knowledge. He also warmly interested himself in most of the religious questions, both ephemeral and permanent, of his day; and the erection of the Reformed church in Göttingen was mainly due to his unwearied energy. Like his mentor Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave (, 31 December 1668 – 23 September 1738Underwood, E. Ashworth. "Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years." ''The British Medical Journal'' 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20395297.) was a Dutch botanist, ...

, Haller was a Christian and a collection of his religious thoughts can be read in a compilation of letters to his daughter.

Notwithstanding all this variety of absorbing interests, Haller never felt at home in Göttingen; his untravelled heart kept on turning towards his native Bern, where he had been elected a member of the great council in 1745, and in 1753 he resolved to resign his chair and return to Switzerland.

Botany

Haller made important contributions to botanical taxonomy that are less visible today because he resistedbinomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

, Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

's innovative shorthand for species names that was introduced in 1753 and marks the starting point for botanical nomenclature as accepted today.

Haller was among the first botanists to realize the importance ofThe plant genus ''Halleria'', an attractive shrub from Southern Africa, was named in his honour by Carl Linnaeus.herbaria A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study. The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sheet of paper (called ...to study variation in plants, and he therefore purposely included material from different localities, habitats and developmental phases. Haller also grew many plants from the Alps himself.

Later life

The twenty-one years of his life which followed were largely occupied in the discharge of his duties in the minor political post of a '' Rathausmann'' which he had obtained by lot, and in the preparation of his ''Bibliotheca medica'', the botanical, surgical and anatomical parts of which he lived to complete; but he also found time to write the three philosophical romances ''Usong'' (1771), ''Alfred'' (1773) and ''Fabius and Cato'' (1774), in which his views as to the respective merits of despotism, of limited monarchy and of aristocratic republican government are fully set forth. In about 1773, his poor health forced him to withdraw from public business. He supported his failing strength by means of opium, on the use of which he communicated a paper to the ''Proceedings'' of the Göttingen Royal Society in 1776; the excessive use of the drug is believed, however, to have hastened his death. Haller, who had been three times married, left eight children. The eldest, Gottlieb Emanuel, attained to some distinction as a botanist and as a writer on Swiss historical bibliography (1785–1788, 7 vols). Another son, Albrecht was also a botanist. See also: * History of anatomy in the 17th and 18th centuriesImportance for homoeopathy

Albrecht von Haller is quoted in the footnote to paragraph 108 in the '' Organon of Medicine'', the principal work by the founder ofhomoeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a di ...

, Samuel Hahnemann

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann (; 10 April 1755 – 2 July 1843) was a German physician, best known for creating the pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine called homeopathy.

Early life

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann was ...

. In this paragraph, Hahnemann describes how the curative powers of individual medicines can only be ascertained through accurate observation of their specific effects on ''healthy'' persons:

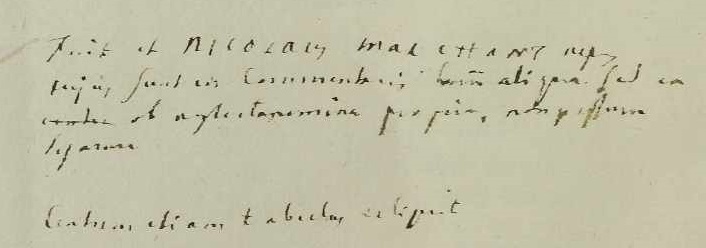

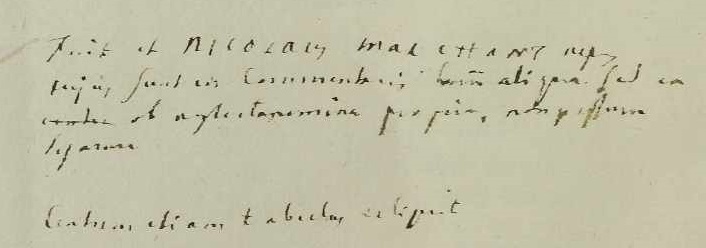

"Not one single physician, as far as I know, during the previous two thousand five hundred years, thought of this so natural, so absolutely necessary and only genuine mode of testing medicines for their pure and peculiar effects in deranging the health of man, in order to learn what morbid state each medicine is capable of curing, except the great and immortal Albrecht von Haller. He alone, besides myself, saw the necessity of this (vide the Preface to the Pharmacopoeia Helvet., Basil, 1771, fol., p. 12); Nempe primum in corpore sano medela tentanda est, sine peregrina ulla miscela; odoreque et sapore ejus exploratis, exigua illiu dosis ingerenda et ad ommes, quae inde contingunt, affectiones, quis pulsus, qui calor, quae respiratia, quaenam excretiones, attendum. Inde ad ductum phaenomenorum, in sano obviorum, transeas ad experimenta in corpore aegroro," etc. But no one, not a single physician, attended to or followed up this invaluable hint."

The quotation from Haller's Preface may be translated from the Latin as follows: "Of course, firstly the remedy must be proved on a healthy body, without being mixed with anything foreign; and when its odour and flavour have been ascertained, a tiny dose of it should be given and attention paid to all the changes of state that take place, what the pulse is, what heat there is, what sort of breathing and what exertions there are. Then in relation to the form of the phenomena in a healthy person from those exposed to it, you should move on to trials on a sick body..."

Reception

In his ''Science of Logic

''Science of Logic'' (''SL''; german: Wissenschaft der Logik, ''WdL''), first published between 1812 and 1816, is the work in which Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel outlined his vision of logic. Hegel's logic is a system of '' dialectics'', i.e., ...

'', Hegel mentions Haller's description of eternity, called by Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

"terrifying" in the '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (A613/B641). According to Hegel, Haller realizes that a conception of eternity as infinite progress is "futile and empty". In a way, Hegel uses Haller's description of eternity as a foreshadowing of his own conception of the true infinite. Hegel claims that Haller is aware that: "only by giving up this empty, infinite progression can the genuine infinite itself become present to him."

Works

* * ** * * * ''Onomatologia medica completa''. Gaum, Ulm 175Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf * * ''Deux Memoires sur le mouvement du sang et sur les effets de la saignée: fondés sur des experiences faites sur des animaux'' 175

* ** * ''Historia stirpium indigenarum Helvetiae inchoata.'' Bernae, 1768. Vol. 1&

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf. * * * * ** * ''Ode sur les Alpes'', 1773 * ''Materia medica oder Geschichte der Arzneyen des Pflanzenreichs''. Vol. 1&2. Leipzig: Haug, 1782

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf. * ''Histoire des Plantes suisses ou Matiere médicale et de l'Usage économique des Plantes par M. Alb. de Haller ... Traduit du Latin''. Vol. 1&2. Berne 179

Digital edition

of the University and State Library Düsseldorf. * * * *

See also

*Hallerian physiology

Hallerian physiology was a theory competing with galvanism in Italy in the late 18th century. It is named after Albrecht von Haller, a Swiss physician who is considered the father of neurology.

The Hallerians' fundamental tenet held that muscular ...

, the theory named after Albrecht von Haller, as an alternative explanation to Galvanism

Galvanism is a term invented by the late 18th-century physicist and chemist Alessandro Volta to refer to the generation of electric current by chemical action. The term also came to refer to the discoveries of its namesake, Luigi Galvani, specif ...

* Karl Ludwig von Haller, Haller's grandson

Notes

References

* * *Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Haller, Albrecht von 18th-century Swiss scientists 1708 births 1777 deaths Fellows of the Royal Society German entomologists Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Scientists from Bern Swiss Christians Swiss expatriates in the Dutch Republic University of Göttingen faculty Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala