Albert Gallatin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

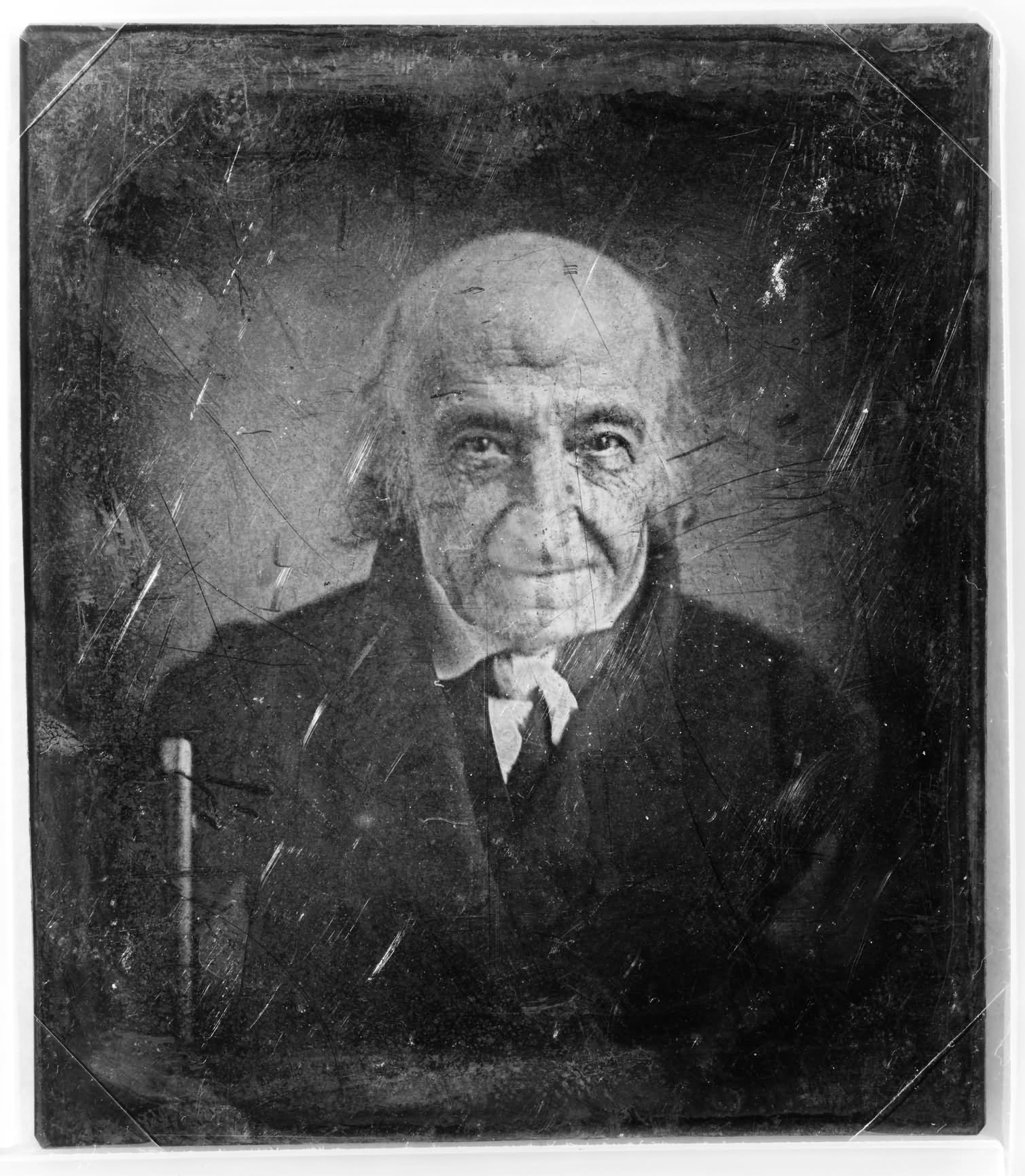

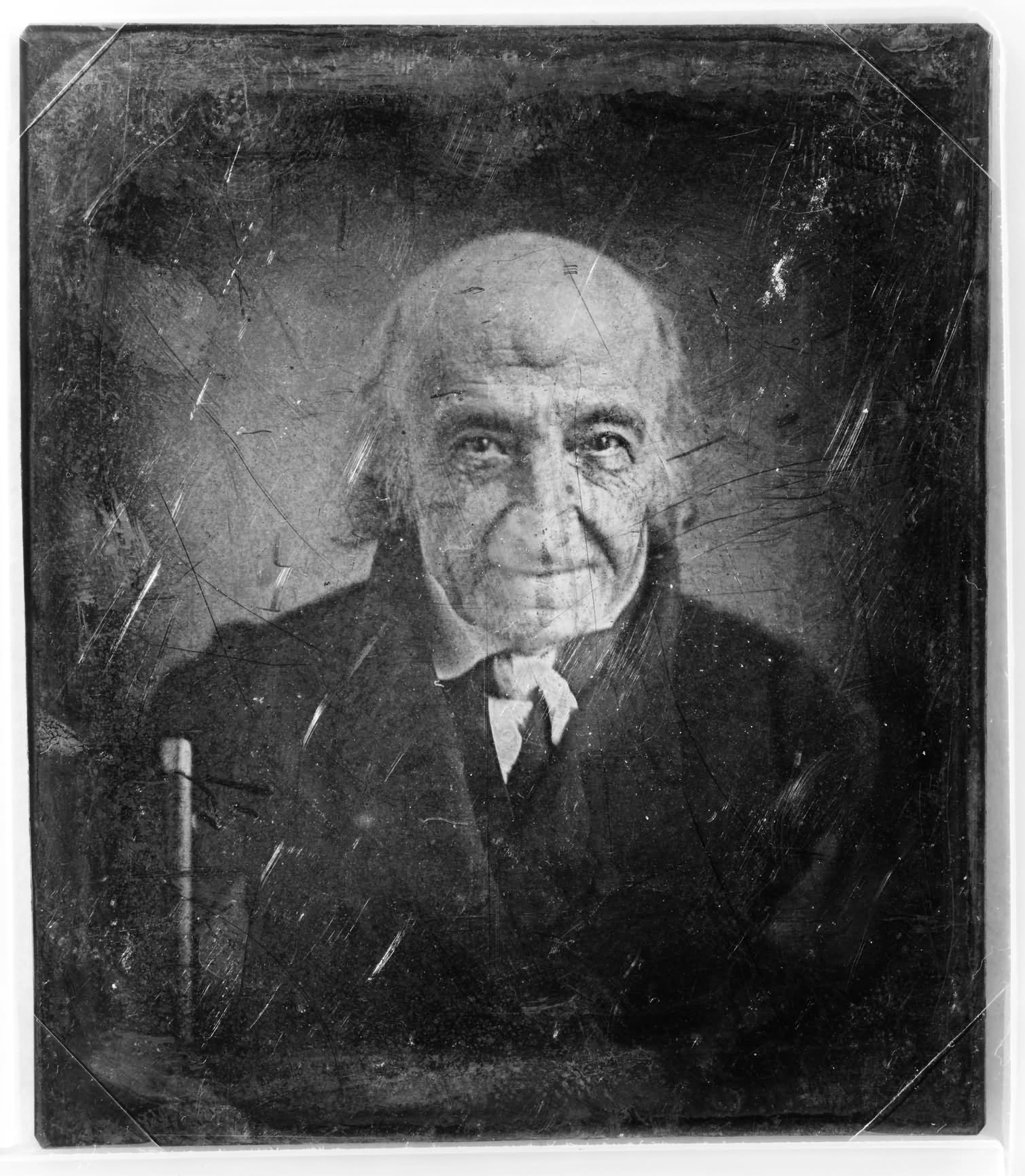

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a

Gallatin was born on January 29, 1761, in

Gallatin was born on January 29, 1761, in

Gallatin's mastery of public finance made him the obvious choice as Jefferson's

Gallatin's mastery of public finance made him the obvious choice as Jefferson's

In 1813, President

In 1813, President

Gallatin moved to New York City in 1828 and became president of the National Bank of New York the following year. He attempted to persuade President Jackson to recharter the Second Bank of the United States, but Jackson vetoed a recharter bill and the Second Bank lost its federal charter in 1836. In 1831, Gallatin helped found

Gallatin moved to New York City in 1828 and became president of the National Bank of New York the following year. He attempted to persuade President Jackson to recharter the Second Bank of the United States, but Jackson vetoed a recharter bill and the Second Bank lost its federal charter in 1836. In 1831, Gallatin helped found

File:GallatinTreas.jpg,

online edition

* * * * * * * * * *

online edition

Volume I

( PDF)

Volume II

( PDF

Volume III

( PDF) * * *

Friendship Hill National Historical Site

Exhibition, 14.10.2011–17 March 2012, Library of Genava, Switzerland *

Albert Gallatin's papers

at the

Genevan

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

– American politician, diplomat, ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology) ...

and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

", he was a leading figure in the early years of the United States, helping shape the new republic's financial system and foreign policy. Gallatin was a prominent member of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

, represented Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in both chambers of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, and held several influential roles across four presidencies, most notably as the longest serving U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. He is also known for his contributions to academia, namely as the founder of New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

and cofounder of the American Ethnological Society

The American Ethnological Society (AES) is the oldest professional anthropological association in the United States.

History of the American Ethnological Society

Albert Gallatin and John Russell Bartlett founded the American Ethnological Societ ...

.

Gallatin was born in Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

in present-day Switzerland and spoke French as a first language. Inspired by the ideals of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, he immigrated to the United States in the 1780s, settling in western Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. He served as a delegate to the 1789 Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention and won election to the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Gallatin was elected to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

in 1793, emerging as a leading Anti-Federalist

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

and opponent of Alexander Hamilton's economic policies. However, he was soon removed from office on a party-line vote

A party-line vote in a deliberative assembly (such as a constituent assembly, parliament, or legislature) is a vote in which a substantial majority of members of a political party vote the same way (usually in opposition to the other political ...

due to not meeting requisite citizenship requirements; returning to Pennsylvania, Gallatin helped calm many angry farmers during the Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

.

Gallatin won election to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in 1795, where he helped establish the House Ways and Means Committee

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other progra ...

. He became the chief spokesman on financial matters for the Democratic-Republican Party and led opposition to the Federalist economic program. Gallatin helped Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

prevail in the contentious presidential election of 1800, and his reputation as a prudent financial manager led to his appointment as Treasury Secretary

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

. Under Jefferson, Gallatin reduced government spending, instituted checks and balances for government expenditures, and financed the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

. He retained his position through James Madison's administration until February 1814, maintaining much of Hamilton's financial system while presiding over a reduction in the national debt. Gallatin served on the American commission that agreed to the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, which ended the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

. In the aftermath of the war, he helped found the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

.

Declining another term at the Treasury, Gallatin served as Ambassador to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

from 1816 to 1823, struggling with scant success to improve relations during the Bourbon Restoration. In the election of 1824, Gallatin was nominated for Vice President by the Democratic-Republican Congressional caucus

A congressional caucus is a group of members of the United States Congress that meet to pursue common legislative objectives. Formally, caucuses are formed as congressional member organizations (CMOs) through the United States House of Represent ...

, but never wanted the position and ultimately withdrew due to a lack of popular support. In 1826 and 1827, he served as the ambassador to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and negotiated several agreements, such as a ten-year extension of the joint occupation of Oregon Country. He thereafter retired from politics and dedicated the rest of his life to various civic, humanitarian, and academic causes. He became the first president of the New York branch of the National Bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

from 1831 to 1839, and in 1842 joined John Russell Bartlett to establish the American Ethnological Society; his studies of Native American languages have earned him the moniker, "father of American ethnology." Gallatin remained active in public life as an outspoken opponent of slavery and fiscal irresponsibility and an advocate for free trade and individual liberty.

Early life

Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

, and was until 1785 a citizen of the Republic of Geneva. His parents were the wealthy Jean Gallatin and his wife Sophie Albertine Rollaz. Gallatin's family had great influence in the Republic of Geneva, and many family members held distinguished positions in the magistracy and the army. Jean Gallatin, a prosperous merchant, died in 1765, followed by Sophie in April 1770. Now orphaned, Gallatin was taken into the care of Mademoiselle Pictet, a family friend and distant relative of Gallatin's father. In January 1773, Gallatin was sent to study at the elite Academy of Geneva. While attending the academy, Gallatin read deeply the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

and Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

, along with the French Physiocrats

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists who believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricultur ...

; he became dissatisfied with the traditionalism of Geneva. A student of the Enlightenment, he believed in the nobility of human nature and that when freed from social restrictions, it would display admirable qualities and greater results in both the physical and the moral world. The democratic spirit of the United States attracted him and he decided to emigrate.

In April 1780, Gallatin secretly left Geneva with his classmate Henri Serre. Carrying letters of recommendation from eminent Americans (including Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

) that the Gallatin family procured, the young men left France in May, sailing on an American ship, "the Kattie". They reached Cape Ann

Cape Ann is a rocky peninsula in northeastern Massachusetts, United States on the Atlantic Ocean. It is about northeast of Boston and marks the northern limit of Massachusetts Bay. Cape Ann includes the city of Gloucester and the towns of ...

on July 14 and arrived in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

the next day, traveling the intervening thirty miles by horseback. Bored with monotonous Bostonian life, Gallatin and Serre set sail with a Swiss female companion to the settlement of Machias, located on the northeastern tip of the Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

frontier. At Machias, Gallatin operated a bartering venture, in which he dealt with a variety of goods and supplies. He enjoyed the simple life and the natural environment surrounding him.Stevens (1888), p16. Gallatin and Serre returned to Boston in October 1781 after abandoning their bartering venture in Machias. Friends of Pictet, who had learned that Gallatin had traveled to the United States, convinced Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

to employ Gallatin as a French tutor.

Gallatin disliked living in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, instead preferring to become a farmer in the Trans-Appalachia

The area in United States west of the Appalachian Mountains and extending vaguely to the Mississippi River, spanning the lower Great Lakes to the upper south, is a region known as trans-Appalachia, particularly when referring to frontier times. It ...

n West, which at that point was the frontier of American settlement. He became the interpreter and business partner of a French land speculator, Jean Savary, and traveled throughout various parts of the United States in order to purchase undeveloped Western lands. In 1785, he became an American citizen after he swore allegiance to the state of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, fulfilling the requirements of citizenship as established under Article IV of the Articles of Confederation. Gallatin inherited a significant sum of money the following year, and he used that money to purchase a 400-acre plot of land in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Fayette County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is located in southwestern Pennsylvania, adjacent to Maryland and West Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 128,804. Its county seat is Uniontown. The county wa ...

. He built a stone house named Friendship Hill on the new property. Gallatin co-founded a company designed to attract Swiss settlers to the United States, but the company proved unable to attract many settlers.

Marriage and family

In 1789, Gallatin married Sophie Allègre, the daughter of a Richmond boardinghouse owner, but Allègre died just five months into the marriage. He was in mourning for a number of years and seriously considered returning to Geneva. However, on November 1, 1793, he married Hannah Nicholson, daughter of the well-connected Commodore James Nicholson. They had two sons and four daughters: Catherine, Sophia, Hannah Marie, Frances,James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguati ...

, and Albert Rolaz Gallatin. Catherine, Sophia and Hannah Marie all died as infants. Gallatin's marriage proved to be politically and economically advantageous, as the Nicholsons enjoyed connections in New York, Georgia, and Maryland. With most of his business ventures unsuccessful, Gallatin sold much of his land, excluding Friendship Hill, to Robert Morris; he and his wife would instead live in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

and other coastal cities for most of the rest of their lives.

Early political career

Pennsylvania legislature and United States Senate

In 1788, Gallatin was elected as a delegate to a state convention to discuss possible revisions to the United States Constitution. In the next two years, he served as a delegate to a state constitutional convention and won election to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. As a public official, he aligned withAnti-Federalists

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

and spent much of his time in the state and national capital of Philadelphia. His service on the Ways and Means Committee earned him a strong reputation as an expert in finance and taxation.

Gallatin won election to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

in early 1793, and he took his seat in December of that year. He quickly emerged as a prominent opponent of Alexander Hamilton's economic program but was declared ineligible for a seat in the Senate in February 1794 because he had not been a citizen for the required nine years prior to election. The dispute itself had important ramifications. At the time, the Senate held closed sessions. However, with the American Revolution only a decade ended, the senators were leery of anything which might hint that they intended to establish an aristocracy, so they opened up their chamber for the first time for the debate over whether to unseat Gallatin. Soon after, open sessions became standard procedure for the Senate.

Whiskey Rebellion

Gallatin had strongly opposed the 1791 establishment of an excise tax onwhiskey

Whisky or whiskey is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky is typically aged in wooden ...

, as whiskey trade and production constituted an important part of the Western economy. In 1794, after Gallatin had been removed from the Senate and returned to Friendship Hill, the Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

broke out among disgruntled farmers opposed to the federal collection of the whiskey tax. Gallatin did not join in the rebellion, but criticized the military response of the President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

's administration as an overreaction. Gallatin helped persuade many of the angered farmers to end the rebellion, urging them to accept that "if any one part of the Union are suffered to oppose by force the determination of the whole, there is an end to government itself and of course to the Union." The rebellion collapsed as the army moved near, and there was no fighting.

House of Representatives

In the aftermath of the Whiskey Rebellion, Gallatin won election to theUnited States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, taking his seat in March 1795. Upon his return to Congress, Gallatin became the leading financial expert of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

. In 1796, Gallatin published ''A Sketch on the Finances of the United States'', which discussed the operations of the Treasury Department and strongly attacked the Federalist Party's financial program. Some historians and biographers believe that Gallatin founded the House Ways and Means Committee

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other progra ...

in order to check Hamilton's influence over financial issues, but historian Patrick Furlong argues that Hamilton's Federalist allies were actually responsible for founding the committee. After James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

declined to seek re-election in 1796, Gallatin emerged as the Democratic-Republican leader in the House of Representatives. During the Quasi-War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

with France, Gallatin criticized military expenditures and opposed passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

. In the contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

that decided the outcome of the 1800 presidential election, Gallatin helped Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

secure victory over his ostensible running mate, Aaron Burr.

Secretary of the Treasury

Jefferson administration

Gallatin's mastery of public finance made him the obvious choice as Jefferson's

Gallatin's mastery of public finance made him the obvious choice as Jefferson's Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

; as Jefferson put it, Gallatin was "the only man in the United States who understands, through all the labyrinths Hamilton involved it, the precise state of the Treasury." Gallatin received a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

in May 1801 and was confirmed by the Senate in January 1802. Along with Secretary of State Madison and Jefferson himself, Gallatin became one of the three key officials in the Jefferson administration. As Jefferson and Madison spent the majority of the summer months at their respective estates, Gallatin was frequently left to preside over the operations of the federal government. He also acted as a moderating force on Jefferson's speeches and policies, in one case convincing Jefferson to refrain from calling for the abolition of the General Welfare Clause. Gallatin also argued against the United States going into trade with the newly liberated Haiti, going as far as to claim that the right of self-determination should be denied to others occasionally, especially if those "others" in question were not white.

With Gallatin taking charge of fiscal policy, the new administration sought to lower taxation (though not import duties), spending, and the national debt; debt reduction in particular had long been a key goal of the party and Gallatin himself. When Gallatin took office in 1801, the national debt stood at $83 million. By 1812, the U.S. national debt had fallen to $45.2 million. Burrows says of Gallatin:

His own fears of personal dependency and his small-shopkeeper's sense of integrity, both reinforced by a strain of radical republican thought that originated in England a century earlier, convinced him that public debts were a nursery of multiple public evils—corruption, legislative impotence, executive tyranny, social inequality, financial speculation, and personal indolence. Not only was it necessary to extinguish the existing debt as rapidly as possible, he argued, but Congress would have to ensure against the accumulation of future debts by more diligently supervising government expenditures.Shortly after taking office, Gallatin worked with House Ways and Means Committee Chairman John Randolph to reduce federal spending and reduce or abolish all internal taxes, including the tax on whiskey. He presided over dramatic reductions in military spending, particularly for the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. Despite his opposition to debt, Gallatin strongly supported and arranged the financing for the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, in which the U.S. bought French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

. Both Jefferson and Gallatin regarded control of the port of , which was ceded in the purchase, as the key to the development of the Western United States. Jefferson had doubts about the constitutionality of the purchase, but Gallatin helped convince the president that a constitutional amendment authorizing the purchase was impractical and unnecessary. Gallatin also championed and helped plan the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

to explore lands west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

.

Before and after the Louisiana Purchase, Gallatin presided over a major expansion of public land sales. With the goal of selling land directly to settlers rather than to land speculators, Gallatin increased the number of federal land offices from four to eighteen. In 1812, Congress established the General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an independent agency of the United States government responsible for public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 to take over functions previously conducted by the United States Department o ...

as part of the Department of Treasury, charging the new office with overseeing public lands. To help develop western lands, Gallatin advocated for internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

such as roads and canals, especially those that would connect to territories west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1805, despite his earlier constitutional reservations, Jefferson announced his support for federally financed infrastructure projects. Three years later, Gallatin put forward his ''Report on Roads and Canals'', in which he advocated for a $20 million federal infrastructure program. Among his proposals were canals through Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

, the Delmarva Peninsula

The Delmarva Peninsula, or simply Delmarva, is a large peninsula and proposed state on the East Coast of the United States, occupied by the vast majority of the state of Delaware and parts of the Eastern Shore regions of Maryland and Virginia. ...

, and the Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp is a large swamp in the Coastal Plain Region of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina. It is located in parts of the southern Virginia indepe ...

, a road stretching from Maine to Georgia, a series of canals connecting the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

with the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

, and various other canals to connect seaports like Charleston with interior regions. Resistance from many congressional Democratic-Republicans regarding cost, as well as hostilities with Britain, prevented the passage of a major infrastructure bill, but Gallatin did win funding for the construction of the National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and was a main tran ...

. The National Road linked the town of Cumberland, on the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

, with the town of Wheeling, which sat on the Ohio River. Many of Gallatin's other proposals were eventually carried out years later by state and local governments, as well as private actors.

Throughout much of Jefferson's presidency, France and Britain engaged in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. During Jefferson's second term, both the British and French stepped up efforts to prevent American trade with their respective enemy. Particularly offensive to many Americans was the British practice of impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

, in which the British forced captured American sailors to crew British ships. Jefferson sent James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

to Britain to negotiate a renewal and revision of the 1795 Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

, but Jefferson rejected the treaty that Monroe reached with the British. After the 1807 Chesapeake–Leopard affair

The ''Chesapeake''–''Leopard'' affair was a naval engagement off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia, on June 22, 1807, between the British fourth-rate and the American frigate . The crew of ''Leopard'' pursued, attacked, and boarded the Americ ...

, Jefferson proposed, over Gallatin's strong objections, what would become the Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it repr ...

. That act forbade all American ships from engaging in almost all foreign trade, and it remained in place until its repeal in the final days of Jefferson's presidency. Despite Gallatin's objection to the embargo, he was tasked with enforcing it against smugglers, who were able to evade the embargo in various ways. The embargo proved ineffective at accomplishing its intended purpose of punishing Britain and France, and it contributed to growing dissent in New England against the Jefferson administration. Overcoming Jefferson's declining popularity and the resentment at the embargo, Secretary of State Madison won the 1808 presidential election.

Madison administration

After taking office, Madison sought to appoint Gallatin as Secretary of State, which was generally seen as the most prestigious cabinet position. Opposition from the Senate convinced Madison to retain Gallatin as Secretary of the Treasury, and Robert Smith instead received the appointment as Secretary of State. Gallatin was deeply displeased by the appointment of Smith, and he was frequently criticized by Smith's brother, Senator Samuel Smith, as well as journalist William Duane of the influential '' Philadelphia Aurora''. He considered resigning from government service, but Madison convinced him to stay on as a key cabinet official and adviser.McGraw (2012), pp. 285–287 In 1810, Gallatin published ''Report on the Subject of Manufactures'', in which he unsuccessfully urged Congress to create a $20 million federal loan program to support fledgling manufacturers. He was also unable to convince Congress to renew the charter of the First Bank of the United States (commonly known as thenational bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

). Although the national bank had been established as part of Hamilton's economic program, and Jefferson believed that it was "one of the most deadly hostility existing against the principles and form of our Constitution," Gallatin saw the national bank as a key part of the country's financial system. In a letter to Jefferson, Gallatin argued that the bank was indispensable because it served as a place of deposit for government funds, a source of credit, and a regulator of currency. In January 1811, the national bank was effectively abolished after the House and the Senate both defeated bills to recharter the national bank in extremely narrow votes. In response, Gallatin sent a letter to Madison, asking for permission to resign and criticizing the president for various actions, including his failure to take a strong stance on the national bank. Shortly afterwards, Madison replaced Secretary of State Smith with James Monroe, and Gallatin withdrew his resignation request.

Following the repeal of the Embargo Act of 1807, Gallatin was charged with enforcing the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which lifted parts of the trade embargo but still prevented American ships from engaging in trade with the British and French empires. In 1811, Congress replaced the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 with a law known as Macon's Bill Number 2

Macon's Bill Number 2, which became law in the United States on May 14, 1810, was intended to motivate Great Britain and France to stop seizing American ships, cargoes, and crews during the Napoleonic Wars. This was a revision of the original bill ...

, which authorized the president to restore trade with either France or Britain if either promised to respect American neutrality. As with previous embargo policies pursued by the federal government under Jefferson and Madison, Macon's Bill Number 2 proved to be ineffective at halting the attacks on American shipping. In June 1812, Madison signed a declaration of war against Britain, beginning the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

.

Madison ordered an invasion of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

by relying on mostly state militias, but British forces defeated the invasion. The U.S. experienced some successes at sea, but were unable to break a British blockade of the United States. With the abolition of the national bank, the drop in import duties due to the war, and the inability or unwillingness of state banks to furnish credit, Gallatin struggled to fund the war. Reluctantly, he drafted and won passage of several new tax laws, as well as an increase in tariff rates. He also sold U.S. securities

A security is a tradable financial asset. The term commonly refers to any form of financial instrument, but its legal definition varies by jurisdiction. In some countries and languages people commonly use the term "security" to refer to any for ...

to investors, and an infusion of cash from wealthy investors Stephen Girard, John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by History of opium in China, smuggl ...

, and David Parish

David Parish (December 4, 1778April 27, 1826) was a German-born land speculator and financier who played a major role in financing the United States military effort in the War of 1812 and in chartering the Second Bank of the United States."The Am ...

proved critical to the financing of the war. During the War of 1812, the national debt grew dramatically, going from $45 million in early 1812 to $127 million in January 1816.

Diplomat

In 1813, President

In 1813, President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

sent Gallatin to St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

to serve as a negotiator for a peace agreement to end the War of 1812. He was one of four American commissioners who would negotiate the treaty, serving alongside Henry Clay, James Bayard, Jonathan Russell

Jonathan Russell (February 27, 1771 – February 17, 1832) was a United States representative from Massachusetts and diplomat. He served the 11th congressional district from 1821 to 1823 and was the first chair of the House Committee on Foreig ...

, and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

. Efforts at starting negotiations in Russia quickly collapsed. While waiting abroad in the hope of future negotiations, Gallatin was replaced as Secretary of the Treasury by George W. Campbell, with the expectation that Gallatin would take up his old post upon his return to the United States. Negotiations with the British finally commenced in Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

in mid-1814.

Negotiations at Ghent lasted for four months. The British could have chosen to shift resources to North America after the temporary defeat of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in April 1814, but, as Gallatin learned from Alexander Baring, many in Britain were tired of fighting. In December 1814, the two sides agreed to sign the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, which essentially represented a return to the status quo ante bellum. The treaty did not address the issue of impressment, but that issue became a moot point after the British and their allies defeated Napoleon for a final time at the June 1815 Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

. Gallatin's patience and skill in dealing with not only the British but also his fellow members of the American commission, including Clay and Adams, made the treaty "the special and peculiar triumph of Mr. Gallatin." After the end of the war, Gallatin negotiated a commercial treaty providing for a resumption of trade between the United States and Britain.McGraw (2012), pp. 309–314 Though the war with Britain had at best been a stalemate, Gallatin was pleased that it resulted in the consolidation of U.S. control over western territories, as the British withdrew their support from dissident Native Americans who had sought to create an independent state

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

in the Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canadian–American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the Canadian p ...

. He also noted that "the war has laid the foundation of permanent taxes and military establishments...under our former system we were becoming too selfish, too much attached exclusively to the acquisition of wealth... ndtoo much confined in our political feelings to local and State objects."

When Gallatin returned from Europe in September 1815, he declined Madison's request to take up his old post as Secretary of the Treasury. He did, however, help convince Congress to charter the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

as a replacement for the defunct First Bank of the United States. Gallatin considered going into business with his longtime friend, John Jacob Astor, but ultimately he accepted appointment as ambassador to France. He served in that position from 1816 to 1823. Though he did not approve of the prevailing ideology of the Bourbon Restoration, Gallatin and his family enjoyed living in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. While serving as ambassador to France, he helped negotiate the Rush–Bagot Treaty

The Rush–Bagot Treaty or Rush–Bagot Disarmament was a treaty between the United States and Great Britain limiting naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, following the War of 1812. It was ratified by the United States Senate o ...

and the Treaty of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

, two treaties with Britain that settled several issues left over from the War of 1812 and established joint Anglo-American over Oregon Country.

Upon returning to the United States, Gallatin agreed to serve as William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

's running mate in the 1824 presidential election, but later withdrew from the race at Crawford's request. Crawford had originally hoped that Gallatin's presence on the ticket would help him win the support of Pennsylvania voters, but the emergence of General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

as a presidential contender caused Crawford to refocus his campaign on other states. Gallatin had never wanted the role and was humiliated when he was forced to withdraw from the race. He was alarmed at the possibility Jackson might win, as he saw Jackson as "an honest man and the idol of the worshippers of military glory, but from incapacity, military habits, and habitual disregard of laws and constitutional provisions, altogether unfit for the office." Ultimately, John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

won the 1824 presidential election in a contingent election held in the House of Representatives. Gallatin and his wife returned to Friendship Hill after the presidential election, living there until 1826. That year, Gallatin accepted appointment as ambassador to Britain. After negotiating an extension of the Anglo-American control of Oregon Country, Gallatin returned to the United States in November 1827.

Later life

Gallatin moved to New York City in 1828 and became president of the National Bank of New York the following year. He attempted to persuade President Jackson to recharter the Second Bank of the United States, but Jackson vetoed a recharter bill and the Second Bank lost its federal charter in 1836. In 1831, Gallatin helped found

Gallatin moved to New York City in 1828 and became president of the National Bank of New York the following year. He attempted to persuade President Jackson to recharter the Second Bank of the United States, but Jackson vetoed a recharter bill and the Second Bank lost its federal charter in 1836. In 1831, Gallatin helped found New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

, and in 1843 he was elected president of the New York Historical Society. In the mid-1840s, he opposed President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

's expansionist policies and wrote a widely-read pamphlet, ''Peace with Mexico'', that called for an end to the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

.

Gallatin was deeply interested in Native Americans, and he favored their assimilation into European-American culture as an alternative to forced relocation

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

.McGraw (2012), p. 322 He drew upon government contacts to research Native Americans, gathering information through Lewis Cass, explorer William Clark, and Thomas McKenney of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Gallatin developed a personal relationship with Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

tribal leader John Ridge

John Ridge, born ''Skah-tle-loh-skee'' (ᏍᎦᏞᎶᏍᎩ, Yellow Bird) ( – 22 June 1839), was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He went to Cornwall, Connecticut, to study at the Foreign Mis ...

, who provided him with information on the vocabulary and the structure of the Cherokee language. Gallatin's research resulted in two published works: ''A Table of Indian Languages of the United States'' (1826) and ''Synopsis of the Indian Tribes of North America'' (1836). His research led him to conclude that the natives of North and South America were linguistically and culturally related and that their common ancestors had migrated from Asia in prehistoric times. Later research efforts include examination of selected Pueblo

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

societies, the Akimel O'odham ( Pima) peoples, and the Maricopa

Maricopa can refer to:

Places

* Maricopa, Arizona, United States, a city

** Maricopa Freeway, a piece of I-10 in Metropolitan Phoenix

** Maricopa station, an Amtrak station in Maricopa, Arizona

* Maricopa County, Arizona, United States

* Marico ...

of the Southwest. In 1843, he co-founded the American Ethnological Society

The American Ethnological Society (AES) is the oldest professional anthropological association in the United States.

History of the American Ethnological Society

Albert Gallatin and John Russell Bartlett founded the American Ethnological Societ ...

, serving as the society's first president. Due to his studies of the languages of the Native Americans, he has been called "the father of American ethnology."

The health of both Gallatin and his wife declined in the late 1840s, and Hannah died in May 1849. On August 12, 1849, Gallatin died in Astoria, now in the Borough of Queens, New York at age 88. He is interred at Trinity Churchyard

The parish of Trinity Church has three separate burial grounds associated with it in New York City. The first, Trinity Churchyard, is located in Lower Manhattan at 74 Trinity Place, near Wall Street and Broadway. Alexander Hamilton, Albert Galla ...

in New York City. Prior to his death, Gallatin had been the last surviving member of the Jefferson cabinet and the last surviving senator from the 18th century.

Legacy

Gallatin is commemorated in the naming of a number of counties, roads, and streets, as well as through his association with New York University. TheGallatin River

The Gallatin River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 120 mi (193 km long), in the U.S. states of Wyoming and Montana. It is one of three rivers, along with the Jefferson and Madison, that converge near Three Forks ...

, named by the Lewis and Clark expedition, is one of three rivers (along with the Jefferson River

The Jefferson River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the U.S. state of Montana. The Jefferson River and the Madison River form the official beginning of the Missouri at Missouri Headwaters State Park near Three F ...

and the Madison River

The Madison River is a headwater tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 183 miles (295 km) long, in Wyoming and Montana. Its confluence with the Jefferson and Gallatin rivers near Three Forks, Montana forms the Missouri River.

Th ...

) that converge near Three Forks, Montana

Three Forks is a city in Gallatin County, Montana, United States and is located within the watershed valley system of both the Missouri and Mississippi rivers drainage basins — and is historically considered the birthplace or start of the M ...

to form the Missouri River. The town of Three Forks is in Gallatin County, Montana, and Montana also hosts Gallatin National Forest

The Gallatin National Forest (now known as the Custer-Gallatin National Forest) is a United States National Forest located in South-West Montana. Most of the Custer-Gallatin goes along the state's southern border, with some of it a part of North- ...

and Gallatin Range

The Gallatin Range is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains, located in the U.S. states of Montana and Wyoming. It includes more than 10 mountains over . The highest peak in the range is Electric Peak at .

The Gallatin Range was named after ...

. Gallatin, Tennessee

Gallatin is a city in and the county seat of Sumner County, Tennessee. The population was 30,278 at the 2010 United States census, 2010 census and 44,431 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Named for United States Secretary of the Tr ...

, the seat of Sumner County and Gallatin County, Kentucky

Gallatin County, is a county located in the northern part of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Its county seat is Warsaw. The county was founded in 1798 and named for Albert Gallatin, the Secretary of the Treasury under President Thomas Jefferson. ...

are also named for Gallatin. Gallatin's home of Friendship Hill is maintained by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propert ...

. A statue of Gallatin stands at the northern entrance of the Treasury Building

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in ...

; a statue of Hamilton stands at the building's southern entrance. The Albert Gallatin Area School District, located in southwestern Fayette County, Pennsylvania, and having contained within Gallatin's home, Friendship Hill, is also named after Gallatin. Businessman Albert Gallatin Edwards

Albert Gallatin Edwards (October 15, 1812 – April 19, 1892) was an Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury under President of the United States Abraham Lincoln and founder of brokerage firm A. G. Edwards.

Edwards was born in Kentucky in 1812 a ...

(who founded his eponymous brokerage firm in 1887 which folded into Wachovia

Wachovia was a diversified financial services company based in Charlotte, North Carolina. Before its acquisition by Wells Fargo and Company in 2008, Wachovia was the fourth-largest bank holding company in the United States, based on total asset ...

in 2007) was named after Gallatin.

Gallatin's name is associated with NYU's Gallatin School of Individualized Study.

In 1791, Gallatin was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

Statue of Albert Gallatin

''Albert Gallatin'' is a bronze statue by James Earle Fraser. It commemorates Albert Gallatin, who founded New York University and served as United States Secretary of the Treasury.

It is located north of the Treasury Building (Washington, D. ...

in front of the northern entrance to the United States Treasury Building

File:Alby Gallatin.JPG, Albert Gallatin House; Friendship Hill National Historic Site

Notes

See also

*Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (October 6, 1770 – November 20, 1843) was a Swiss-American surveyor who is considered the forefather of both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Institute of Standards and Techn ...

* Friendship Hill National Historic Site

Friendship Hill was the home of early American politician and statesman Albert Gallatin (1761–1849). Gallatin was a U.S. Congressman, the longest-serving Secretary of the Treasury under two presidents, and ambassador to France and Great Britain ...

* Gallatin Bank Building

* List of foreign-born United States Cabinet members

there have been 23 members appointed to the Cabinet of the United States who had been born outside the present-day United States.

Alexander Hamilton, one of the Founding Fathers who signed the United States Constitution, was the first Cabin ...

* List of United States senators born outside the United States

This is a list of United States senators born outside the United States. It includes senators born in foreign countries (whether to American or foreign parents). The list also includes senators born in territories outside the United States that wer ...

Explanatory notes

References

Works cited

*online edition

* * * * * * * * * *

online edition

Further reading

Secondary sources

* * * * * * * * * *Primary sources

*Volume I

( PDF)

Volume II

Volume III

( PDF) * * *

External links

* * * * * * *Friendship Hill National Historical Site

Exhibition, 14.10.2011–17 March 2012, Library of Genava, Switzerland *

Albert Gallatin's papers

at the

Indiana State Library

The Indiana State Library and Historical Bureau is a public library building, located in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is the largest public library in the state of Indiana, housing over 60,000 manuscripts. Established in 1934, the library has gather ...

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gallatin, Albert

1761 births

1849 deaths

18th-century American politicians

19th-century American politicians

19th-century American diplomats

18th-century people from the Republic of Geneva

United States Secretaries of the Treasury

Jefferson administration cabinet members

Madison administration cabinet members

Anti-Administration Party United States senators from Pennsylvania

Democratic-Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania

Ambassadors of the United States to France

Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom

Activists from Maine

Activists from Pennsylvania

Activists from Virginia

American anti-war activists

People from Machias, Maine

Politicians from Morgantown, West Virginia

Politicians from Pittsburgh

American ethnologists

Linguists of indigenous languages of North America

New York University faculty

Harvard University faculty

Members of the American Antiquarian Society

People of the Whiskey Rebellion

American people of the War of 1812

Burials at Trinity Church Cemetery

Members of the United States Senate declared not entitled to their seat