Alan Duncan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

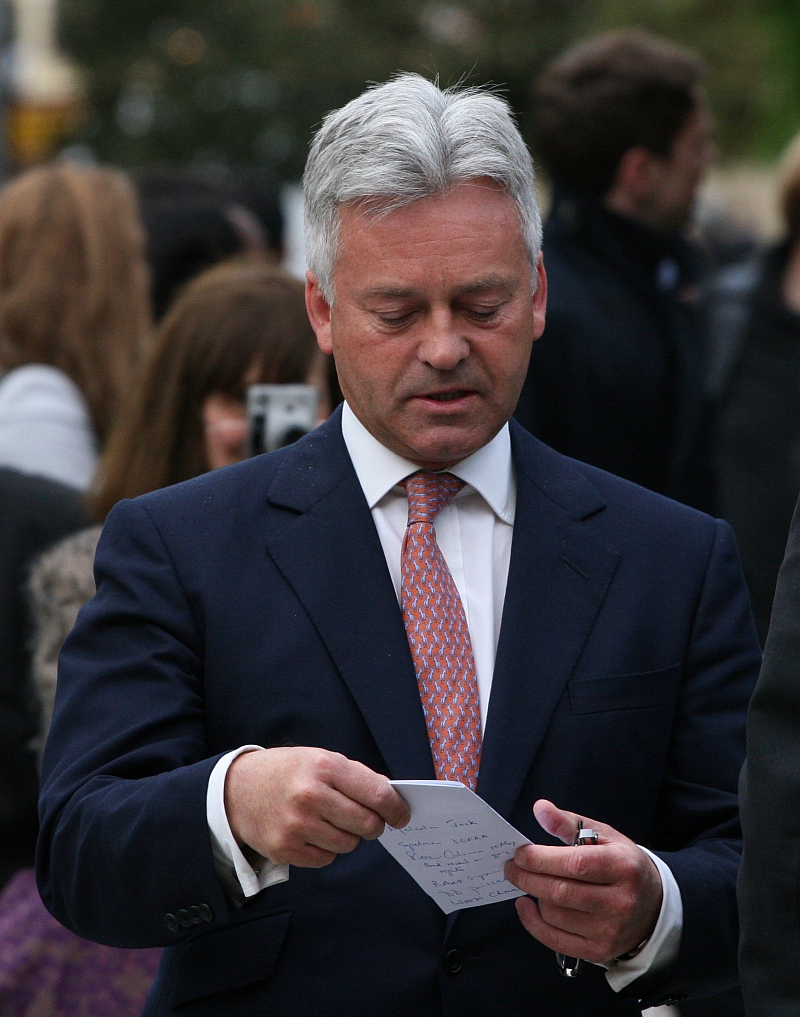

Sir Alan James Carter Duncan (born 31 March 1957) is a British former Conservative Party politician who served as

On 15 May 2009, the satirical BBC programme '' Have I Got News for You'' showed footage of Duncan's previous appearance on the show in which he boasted about his second home allowance, denied that he should pay any of the money back and stated it was "a great system". The show then cut to footage of David Cameron announcing that Duncan would return money to the fees office, followed by Duncan's personal apology, in which he called for the system to be changed.

On 14 August, Duncan said (whilst being filmed without his knowledge by ''Don't Panic''), that MPs, who were at the time paid around £64,000 a year, were having, "to live on rations and are treated like shit. I spend my money on my garden and claim a tiny fraction on what is proper. And I could claim the whole lot, but I don't." These remarks attracted the attention of the press, and were criticised by commentators from all sides. Duncan apologised once more, and Cameron, though critical of Duncan's comments, denied that he would sack him from the Shadow Cabinet. Despite these assurances, on 7 September 2009, Duncan was "demoted" from the Shadow Cabinet, to become Shadow Minister for Prisons, after he and Cameron came to an agreement that his position was untenable.

On 15 May 2009, the satirical BBC programme '' Have I Got News for You'' showed footage of Duncan's previous appearance on the show in which he boasted about his second home allowance, denied that he should pay any of the money back and stated it was "a great system". The show then cut to footage of David Cameron announcing that Duncan would return money to the fees office, followed by Duncan's personal apology, in which he called for the system to be changed.

On 14 August, Duncan said (whilst being filmed without his knowledge by ''Don't Panic''), that MPs, who were at the time paid around £64,000 a year, were having, "to live on rations and are treated like shit. I spend my money on my garden and claim a tiny fraction on what is proper. And I could claim the whole lot, but I don't." These remarks attracted the attention of the press, and were criticised by commentators from all sides. Duncan apologised once more, and Cameron, though critical of Duncan's comments, denied that he would sack him from the Shadow Cabinet. Despite these assurances, on 7 September 2009, Duncan was "demoted" from the Shadow Cabinet, to become Shadow Minister for Prisons, after he and Cameron came to an agreement that his position was untenable.

Duncan is a right-wing libertarian. ''The Guardian'' has variously described him as 'economically libertarian' and 'socially libertarian'. He has been described as the 'liberal, urbane face of the Conservative Party'. He was a moderniser within the Conservative Party.

One of the chapters in his book '' Saturn's Children'' is devoted to an explanation of his support for the legalisation of all drugs. This chapter was removed when the paperback edition was published to prevent embarrassment to the Party leadership, however Duncan at one time posted the chapter on his website, "for the benefit of the enquiring student". Duncan believes in minimising the size of government, and in ''Saturn’s Children'' advocated limiting government responsibility to essential services such as defence, policing and health.

In 2002, Duncan was described by the BBC as a "staunch" Eurosceptic. However, he declared for the 'Remain' camp in the run-up to the UK's referendum on EU membership. On 2 October 2017, Duncan spoke at the Chicago Council of Global Affairs. In his speech he attributed Britain's majority vote to leave the EU to a "blue-collar tantrum against immigration".

He is on the council of the

Duncan is a right-wing libertarian. ''The Guardian'' has variously described him as 'economically libertarian' and 'socially libertarian'. He has been described as the 'liberal, urbane face of the Conservative Party'. He was a moderniser within the Conservative Party.

One of the chapters in his book '' Saturn's Children'' is devoted to an explanation of his support for the legalisation of all drugs. This chapter was removed when the paperback edition was published to prevent embarrassment to the Party leadership, however Duncan at one time posted the chapter on his website, "for the benefit of the enquiring student". Duncan believes in minimising the size of government, and in ''Saturn’s Children'' advocated limiting government responsibility to essential services such as defence, policing and health.

In 2002, Duncan was described by the BBC as a "staunch" Eurosceptic. However, he declared for the 'Remain' camp in the run-up to the UK's referendum on EU membership. On 2 October 2017, Duncan spoke at the Chicago Council of Global Affairs. In his speech he attributed Britain's majority vote to leave the EU to a "blue-collar tantrum against immigration".

He is on the council of the

Alan Duncan MP

''Official constituency website''

Alan Duncan Appearances

C-SPAN

Alan Duncan Profile

at ''

Minister of State for International Development

, type = Department

, logo = DfID.svg

, logo_width = 180px

, logo_caption =

, picture = File:Admiralty Screen (411824276).jpg

, picture_width = 180px

, picture_caption = Department for International Development (London office) (far right ...

from 2010 to 2014 and as Minister of State for Europe and the Americas from 2016 to 2019. He was the Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for Rutland and Melton from 1992 to 2019.

He began his career in the oil industry with Royal Dutch Shell

Shell plc is a British multinational oil and gas company headquartered in London, England. Shell is a public limited company with a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and secondary listings on Euronext Amsterdam and the New Yo ...

, and was first elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in the 1992 general election. After gaining several minor positions in the government of John Major, he played a key role in William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

's successful bid for the Conservative leadership in 1997

File:1997 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The movie set of ''Titanic'', the highest-grossing movie in history at the time; '' Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone'', is published; Comet Hale-Bopp passes by Earth and becomes one of ...

. Duncan received several promotions to the Conservative front bench, and eventually joined the Shadow Cabinet after the 2005 general election. He stood for the Conservative leadership in 2005, but withdrew early on because of a lack of support. Eventual winner David Cameron appointed him Shadow Secretary of State for Trade and Industry

The secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The incumbent is a memb ...

in December 2005; the name of the department he shadowed was changed to Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform in July 2007.

Following the 2010 general election, the new Conservative Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Cameron appointed Duncan as Minister of State

Minister of State is a title borne by politicians in certain countries governed under a parliamentary system. In some countries a Minister of State is a Junior Minister of government, who is assigned to assist a specific Cabinet Minister. In ...

for International Development. He left this post following the government reshuffle in July 2014, and was subsequently appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George in September 2014, for services to international development and to UK–Middle East relations. While on the backbenches, Duncan served on the Intelligence and Security Committee

The Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC) is a statutory joint committee of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, appointed to oversee the work of the UK intelligence community.

The committee was established in 1994 by the ...

between 2015 and 2016.

After two years out of government, he returned to frontline politics when new Prime Minister Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Lady May (; née Brasier; born 1 October 1956) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served in David Cameron's cabi ...

appointed him as Minister for Europe and the Americas, and effective deputy to then- Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (; born 19 June 1964) is a British politician, writer and journalist who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He previously served as F ...

, in July 2016. Duncan resigned as Minister of State on 22 July 2019 citing Johnson's election to the Tory leadership and, hence, the UK's premiership.

He became the first openly gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

Conservative Member of Parliament, publicly coming out in 2002.

Early life

Duncan was born inRickmansworth

Rickmansworth () is a town in southwest Hertfordshire, England, about northwest of central London and inside the perimeter of the M25 motorway. The town is mainly to the north of the Grand Union Canal (formerly the Grand Junction Canal) and ...

, Hertfordshire, the second son of James Grant Duncan, an RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

wing commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

, and his wife Anne Duncan (née Carter), a teacher. The family travelled much, following Duncan's father on NATO postings, including in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, Italy, and Norway.

Education

Duncan was educated at two independent schools: Beechwood Park School inMarkyate

Markyate is a village and civil parish in north-west Hertfordshire, close to the border with Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

Geography

The name of the village has had several former variants, including ''Markyate Street'', ''Market Street'' and ...

, and Merchant Taylors' School in Northwood, at both of which he was 'Head Monitor' (head boy). He had two brothers, who also attended Beechwood Park School. Their family supported the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, and Duncan ran (and lost) as a Liberal at a school mock election

A mock election is an election for educational demonstration, amusement, or political protest reasons to call for free and fair elections. Less precisely it can refer to a real election purely for advisory (essentially without power) committees o ...

in 1970; two years later he joined the Young Conservatives.

He then attended St John's College, Oxford, where he coxed the college first eight, and was elected President of the Oxford Union in 1979. Whilst there, he formed a friendship with Benazir Bhutto, and ran her successful campaign to become the President of the Oxford Union. He gained a Kennedy Scholarship

Kennedy Scholarships provide full funding for up to ten British post-graduate students to study at either Harvard University or the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Susan Hockfield, the sixteenth president of MIT, described the schol ...

to study at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

between 1981 and 1982.

Business career

After graduating from Oxford, Duncan worked as a trader of oil and refined products, first withRoyal Dutch Shell

Shell plc is a British multinational oil and gas company headquartered in London, England. Shell is a public limited company with a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and secondary listings on Euronext Amsterdam and the New Yo ...

(1979–81) and then for Marc Rich

Marc Rich (born Marcell David Reich; December 18, 1934 – June 26, 2013) was an international commodities trader, hedge fund manager, financier, businessman, and financial criminal. He founded the commodities company Glencore, and was later ind ...

from 1982 to 1988 (Rich became a fugitive from justice in 1983). He worked for Rich in London and Singapore. Duncan used the connections he had built up to be self-employed from 1988 to 1992, acting as a consultant and adviser to foreign governments on oil supplies, shipping and refining.

In 1989, Duncan set up the independent Harcourt Consultants, which advises on oil and gas matters. He made over £1 million after helping fill the need to supply oil to Pakistan after supplies from Kuwait had been disrupted in the Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a Coalition of the Gulf War, 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Ba'athist Iraq, ...

.

Political career

Duncan was an active member of the Battersea Conservative Association from 1979 until 1984, when he moved to live inSingapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, from which he returned in 1986. After Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

resigned in November 1990, he offered his home in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

as the headquarters of John Major's leadership campaign.

Member of Parliament

Duncan first stood for Parliament as aConservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

candidate in the 1987 general election, unsuccessfully contesting the safe Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

seat of Barnsley West and Penistone

Barnsley () is a market town in South Yorkshire, England. As the main settlement of the Metropolitan Borough of Barnsley and the fourth largest settlement in South Yorkshire. In Barnsley, the population was 96,888 while the wider Borough has ...

. For the 1992 general election he was selected as the Conservative candidate for Rutland and Melton, a safe Conservative seat, which he retained with a 59% share of the votes cast. In the Labour landslide of 1997, his proportion of the vote was reduced to 46% but has since increased to 48% in 2001, 51% in 2005 and 51% in 2010.

From 1993 to 1995, Duncan was a member of the Social Security Select Committee. His first governmental position was as Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Minister of Health A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental health.

Coun ...

, a position he obtained in December 1993. He resigned from the position within a month, after it emerged that he had used the Right to Buy

The Right to Buy scheme is a policy in the United Kingdom, with the exception of Scotland since 1 August 2016 and Wales from 26 January 2019, which gives secure tenants of councils and some housing associations the legal right to buy, at a large ...

programme to make profits on property deals. It emerged that he had lent his elderly next-door neighbour money to buy his home under the Right to Buy legislation. The neighbour bought an 18th-century council house

A council house is a form of British public housing built by local authorities. A council estate is a building complex containing a number of council houses and other amenities like schools and shops. Construction took place mainly from 1919 ...

at a significant discount and sold it to Duncan just over three years later. Gyles Brandreth

Gyles Daubeney Brandreth (born 8 March 1948) is an English broadcaster, writer and former politician. He has worked as a television presenter, theatre producer, journalist, author and publisher.

He was a presenter for TV-am's '' Good Morning ...

describes this event in his diary as "little Alan Duncan has fallen on his sword. He did it swiftly and with good grace."

After returning to the backbenches, he became Chairman of the Conservative Backbench Constitutional Affairs Committee. He returned to government in July 1995, when he was again appointed a Parliamentary Private Secretary, this time to the Chairman of the Conservative Party

The chairman of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom is responsible for party administration and overseeing the Conservative Campaign Headquarters, formerly Conservative Central Office.

When the Conservatives are in government, the off ...

, Brian Mawhinney. In November 1995, Duncan performed a citizen's arrest

A citizen's arrest is an arrest made by a private citizen – that is, a person who is not acting as a sworn law-enforcement official. In common law jurisdictions, the practice dates back to medieval England and the English common law, in which ...

on an Asylum Bill protester who threw paint and flour at Mawhinney on College Green.

Duncan was involved in the 1997 leadership contest, being the right-hand man of William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, the eventual winner. In this capacity, he was called "the closest thing he Conservativeshave to Peter Mandelson

Peter Benjamin Mandelson, Baron Mandelson (born 21 October 1953) is a British Labour Party politician who served as First Secretary of State from 2009 to 2010. He was President of the Board of Trade in 1998 and from 2008 to 2010. He is the ...

". Duncan and Hague had both been at Oxford, both been Presidents of the Oxford Union, and had been close friends since at least the early 1980s.

Front-bench career

As a reward for his loyalty to Hague during the leadership contest, in June 1997, Duncan was entrusted with the positions of Vice Chairman of the Conservative Party and Parliamentary Political Secretary to the Party Leader. He became Shadow Health Minister in June 1998. A year later he was made Shadow Trade and Industry spokesman, and he was appointed a front-bench spokesman on Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs in September 2001. When Michael Howard became Conservative Party leader in November 2003, Duncan became ShadowSecretary of State for Constitutional Affairs

The secretary of state for constitutional affairs was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the business of the Department for Constitutional Affairs. The position existed from 2003 to 200 ...

, but as Howard had significantly reduced the size of the Shadow Cabinet, Duncan was not promoted to the top table. This continued to be the case when he was moved to become Shadow Secretary of State for International Development

The minister of state for development and Africa, formerly the minister of state for development and the secretary of state for international development, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom.

The off ...

in September 2004. However, following the 2005 general election, the Shadow Cabinet was expanded to its original size once more, and Duncan joined it as Shadow Secretary of State for Transport.

He held this position for just seven months, becoming Shadow Secretary of State for Trade and Industry on 7 December 2005, after David Cameron's election to the party leadership the previous day. On 2 July 2007, he was appointed Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform, as new prime minister Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony B ...

had abolished the Department of Trade and Industry the previous week, replacing it with the aforementioned new department. In January 2009, Duncan became Shadow Leader of the House of Commons.

Failed leadership bid

Before the 2005 general election, he was rumoured to be planning a leadership campaign in the event that then-leader Michael Howard stepped down after a (then-likely and later actual) election defeat. On 10 June 2005, Duncan publicly declared his intention of standing in the 2005 leadership election. However, on 18 July 2005, he withdrew from the race, admitting in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' that his withdrawal was due to a lack of 'active lieutenants', and urged the party to abandon those that he dubbed the 'Tory Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalist, militant Islamist, jihadist, and Pasht ...

':

MPs' expenses 2009

On 15 May 2009, the satirical BBC programme '' Have I Got News for You'' showed footage of Duncan's previous appearance on the show in which he boasted about his second home allowance, denied that he should pay any of the money back and stated it was "a great system". The show then cut to footage of David Cameron announcing that Duncan would return money to the fees office, followed by Duncan's personal apology, in which he called for the system to be changed.

On 14 August, Duncan said (whilst being filmed without his knowledge by ''Don't Panic''), that MPs, who were at the time paid around £64,000 a year, were having, "to live on rations and are treated like shit. I spend my money on my garden and claim a tiny fraction on what is proper. And I could claim the whole lot, but I don't." These remarks attracted the attention of the press, and were criticised by commentators from all sides. Duncan apologised once more, and Cameron, though critical of Duncan's comments, denied that he would sack him from the Shadow Cabinet. Despite these assurances, on 7 September 2009, Duncan was "demoted" from the Shadow Cabinet, to become Shadow Minister for Prisons, after he and Cameron came to an agreement that his position was untenable.

On 15 May 2009, the satirical BBC programme '' Have I Got News for You'' showed footage of Duncan's previous appearance on the show in which he boasted about his second home allowance, denied that he should pay any of the money back and stated it was "a great system". The show then cut to footage of David Cameron announcing that Duncan would return money to the fees office, followed by Duncan's personal apology, in which he called for the system to be changed.

On 14 August, Duncan said (whilst being filmed without his knowledge by ''Don't Panic''), that MPs, who were at the time paid around £64,000 a year, were having, "to live on rations and are treated like shit. I spend my money on my garden and claim a tiny fraction on what is proper. And I could claim the whole lot, but I don't." These remarks attracted the attention of the press, and were criticised by commentators from all sides. Duncan apologised once more, and Cameron, though critical of Duncan's comments, denied that he would sack him from the Shadow Cabinet. Despite these assurances, on 7 September 2009, Duncan was "demoted" from the Shadow Cabinet, to become Shadow Minister for Prisons, after he and Cameron came to an agreement that his position was untenable.

Political funding

The Rutland and Melton Constituency Association has received £12,166.66 in donations since 2006. Duncan has received corporate donations from The Biz Club (£6,000, 2006–09), Midland Software Holdings (£8,000, 2007–09), and ABM Holdings (£1,500, 2009). Duncan has also had tens of thousands of pounds from private individual donors.WikiLeaks 2010

According to ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' and ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', to assess the possible policies of a future Conservative government, American Intelligence drew up a dossier on several members of that party, including Duncan. It compiled details of his political associations with leading Conservatives, including William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

. The cable called for further intelligence on "Duncan's relationship with Conservative party leader David Cameron and William Hague", and asked: "What role would Duncan play if the Conservatives form a government? What are Duncan's political ambitions?"

Nuclear power

As shadow business secretary in 2008, Duncan stated, referring to the Hinkley Point C project, that "on no account should there be any kind of subsidy for nuclear power."Middle East

In August 2011 he found himself under pressure to remove a video of himself accusing Israel of a "land grab" in the occupied territories. In an October 2014 speech to theRoyal United Services Institute

The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI, Rusi), registered as Royal United Service Institute for Defence and Security Studies and formerly the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies, is a British defence and security think tank. ...

Duncan said: "Indeed just as we rightly judge someone as unfit for public office if they refuse to recognise Israel, so we should shun anyone who refuses to recognise settlements are illegal. No settlement endorsers should be regarded as fit to stand for public office, remain a member of a mainstream political party or sit in a parliament. How can we accept lawmakers in our country or any other country when they support lawbreakers in another?" In a BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

interview linked to that speech and another given during a House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

debate on Palestinian statehood he said: "All know that the United States is in hock to a very powerful financial lobby which dominates its politics." Commenting on Duncan's statements, a spokesman for the Board of Deputies of British Jews called him "breathtakingly one-sided".

Libyan oil cell

In August 2011, it was reported that Duncan had played an instrumental role in blocking fuel supplies toTripoli, Libya

Tripoli (; ar, طرابلس الغرب, translit= Ṭarābulus al-Gharb , translation=Western Tripoli) is the capital city, capital and largest city of Libya, with a population of about 1.1 million people in 2019. It is located in the northwe ...

, during the Libyan conflict. In April 2011, the former oil trader convinced the UK prime minister to establish the so-called 'Libyan oil cell' which was run out of the Foreign Office.

The cell advised NATO to blockade the port of Zawiya to stifle Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

's war effort. They also helped identify other passages the smugglers were using to get fuel into Libya via Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

.

London-based oil traders were encouraged to sell fuel to rebels in Benghazi, with communication being established between traders and the rebels to route the fuel.

One Whitehall source commented: 'The energy noose tightened around Tripoli's neck. It was much more effective and easier to repair than bombs. It is like taking the key of the car away. You can't move. The great thing is you can switch it all back on again if Gaddafi goes. It is not the same as if you have bombed the whole city to bits.

Appointment to Privy Council

On 28 May 2010 he was appointed to the Privy Council upon the formation of the Coalition government.Comments by Israeli embassy official

In January 2017,Al Jazeera

Al Jazeera ( ar, الجزيرة, translit-std=DIN, translit=al-jazīrah, , "The Island") is a state-owned Arabic-language international radio and TV broadcaster of Qatar. It is based in Doha and operated by the media conglomerate Al Jazeera ...

aired a series entitled ''The Lobby

The terms the Lobby and Lobby journalists collectively characterise the political journalists in the United Kingdom Houses of Parliament. The term derives from the special access they receive to the Members' Lobby. Lobby journalism refers to t ...

''. The last episode showed Shai Masot, an official at the Israeli embassy in London, proposing an attempt to "take down" British "pro-Palestinian" politicians, including Duncan. The leader of the opposition Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialist ...

wrote an open letter to Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Lady May (; née Brasier; born 1 October 1956) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served in David Cameron's cabi ...

objecting to what he called an "improper interference in this country’s democratic process" and urging the prime minister to launch an inquiry on the basis that " is is clearly a national security issue". The Israeli ambassador Mark Regev

Mark Regev ( he, מארק רגב; born 1960) is a former Israeli diplomat and civil servant who is currently the chair of the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy and Foreign Relations at Reichman University. Between June 2020 and April 2021, he ser ...

apologised to Duncan for the "completely unacceptable" comments made in the video. A Foreign Office spokesman, effectively rejecting Corbyn's comments, said it "is clear these comments do not reflect the views of the embassy or government of Israel". Masot resigned shortly after the recordings were made public. Pro-Israel British activists and a former Israel embassy employee complained to Ofcom, but Ofcom dismissed all charges.

Political views

Duncan is a right-wing libertarian. ''The Guardian'' has variously described him as 'economically libertarian' and 'socially libertarian'. He has been described as the 'liberal, urbane face of the Conservative Party'. He was a moderniser within the Conservative Party.

One of the chapters in his book '' Saturn's Children'' is devoted to an explanation of his support for the legalisation of all drugs. This chapter was removed when the paperback edition was published to prevent embarrassment to the Party leadership, however Duncan at one time posted the chapter on his website, "for the benefit of the enquiring student". Duncan believes in minimising the size of government, and in ''Saturn’s Children'' advocated limiting government responsibility to essential services such as defence, policing and health.

In 2002, Duncan was described by the BBC as a "staunch" Eurosceptic. However, he declared for the 'Remain' camp in the run-up to the UK's referendum on EU membership. On 2 October 2017, Duncan spoke at the Chicago Council of Global Affairs. In his speech he attributed Britain's majority vote to leave the EU to a "blue-collar tantrum against immigration".

He is on the council of the

Duncan is a right-wing libertarian. ''The Guardian'' has variously described him as 'economically libertarian' and 'socially libertarian'. He has been described as the 'liberal, urbane face of the Conservative Party'. He was a moderniser within the Conservative Party.

One of the chapters in his book '' Saturn's Children'' is devoted to an explanation of his support for the legalisation of all drugs. This chapter was removed when the paperback edition was published to prevent embarrassment to the Party leadership, however Duncan at one time posted the chapter on his website, "for the benefit of the enquiring student". Duncan believes in minimising the size of government, and in ''Saturn’s Children'' advocated limiting government responsibility to essential services such as defence, policing and health.

In 2002, Duncan was described by the BBC as a "staunch" Eurosceptic. However, he declared for the 'Remain' camp in the run-up to the UK's referendum on EU membership. On 2 October 2017, Duncan spoke at the Chicago Council of Global Affairs. In his speech he attributed Britain's majority vote to leave the EU to a "blue-collar tantrum against immigration".

He is on the council of the Conservative Way Forward

Conservative Way Forward (CWF) is a British pressure and campaigning group, which is Thatcherite in its outlook and agenda. Margaret Thatcher was its founding President.

Conservative Way Forward was founded in 1991 to "defend and build upon th ...

(CWF) group. He is one of the leading British members of Le Cercle

Le Cercle is a secretive, invitation-only foreign policy forum. Its focus has been opposing communism and, in the 1970s and 1980s, supporting apartheid when the group had intimate ties with and funding from South Africa. The group was described b ...

, a secretive foreign policy discussion forum. In contrast to most members of both CWF and Le Cercle, who hold pro-Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Atlanticist

Atlanticism, also known as Transatlanticism, is the belief in or support for a close relationship between the peoples and governments in Northern America (the United States and Canada) and those in Europe (the countries of the European Union, the ...

views, he actively supported John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party, he ...

in the US 2004 presidential election. This surprised some, but Duncan is a friend of Kerry, having met him while at Harvard.

Following the release of the Panama Papers, which contained revelations about David Cameron's income from overseas funds set up by his father, Duncan defended the Prime Minister. He urged Cameron's critics, especially MPs, to "admit that their real point is that they hate anyone who has got a hint of wealth in them" from whose viewpoint it followed that "we risk seeing a House of Commons which is stuffed full of low-achievers". Michael Deacon wrote in ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'': "There are two inferences to draw from Sir Alan’s outburst. One is that he thinks the Commons should only be 'stuffed with' the rich. The second is that he thinks the vast majority of his constituents, not being rich, are 'low-achievers'. Probably not a view to advertise in his next election leaflet".

Personal life

Duncan was the first sitting Conservative MP voluntarily to acknowledge that he is gay; he did this in an interview with ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' on 29 July 2002, although he has said that this came as no surprise to friends. Indeed, in an editorial published on the news of Duncan's coming out, ''The Daily Telegraph'' reported, "The news that Alan Duncan is gay will come as a surprise only to those who have never met him. The bantam Tory frontbencher can hardly be accused of having hidden his homosexuality."

On 3 March 2008, it was announced in the Court & Social page of ''The Daily Telegraph'' that Duncan would be entering into a civil partnership

A civil union (also known as a civil partnership) is a legally recognized arrangement similar to marriage, created primarily as a means to provide recognition in law for same-sex couples. Civil unions grant some or all of the rights of marriage ...

with his partner James Dunseath, which would make him the first member of either the Cabinet or the Shadow Cabinet to enter into a civil partnership. The two were joined as civil partners on 24 July 2008 at Merchant Taylors' Hall in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

.

Duncan has a committed following in the gay community and is active in speaking up for gay rights. He was responsible for formulating the Conservatives' policy response to the introduction of civil partnership legislation in 2004, which he considered his proudest achievement of the Parliament between 2001 and 2005. He was among those who rebelled against his party by voting for an equal age of consent between heterosexuals and homosexuals on numerous occasions between 1998 and 2000. However, he voted against same-sex adoption in 2001.

Works and appearances

Books

Duncan is the author of three published nonfiction books: * (economics) * (political science) * (political memoir of 2016–2020) His pamphlet ''An End to Illusions'' proposed an independent Bank of England, the break-up of clearing banks, reduction of implicit tax subsidies given to owner-occupiers, curtailment of pension fund tax privileges, and new forms of corporate ownership. ''Saturn's Children'' presents a detailed case regarding the history and consequences of government control over institutions and activities which were historically private, to the extent that many citizens assume that privately or communally developed municipal facilities and universities are creations of the state, and that prohibitions on drug use, sex, and personal defence have always existed. ''In the Thick of It'' is Duncan's diary from the eve of the Brexit referendum in 2016 to the UK's eventual exit from the EU.Television and radio

Duncan has appeared four times on the satirical news quiz '' Have I Got News for You'': first appearing on 28 October 2005, then 20 October 2006, and again on 2 May 2008 and 24 April 2009. His 2009 appearance featured a badly receivedironic

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized into ...

joke about murdering the latest Miss California

The Miss California competition selects the representative for the state of California in the Miss America competition.

The pageant began in Santa Cruz in 1924 and was held there in 1925. During the years 1926 through 1946 in years when the Mi ...

, who stated that she opposed same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

s.

He has appeared on many occasions as a panellist on BBC TV's ''Question Time

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

'' and BBC Radio 4's ''Any Questions?

''Any Questions?'' is a British topical discussion programme "in which a panel of personalities from the worlds of politics, media, and elsewhere are posed questions by the audience".

It is typically broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Fridays at 8 p ...

'' In 2006, he took part in a documentary entitled ''How to beat Jeremy Paxman''.

See also

References

External links

Alan Duncan MP

''Official constituency website''

Alan Duncan Appearances

C-SPAN

Alan Duncan Profile

at ''

New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British Political magazine, political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney Webb, Sidney and Beatrice ...

'' Your Democracy

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Duncan, Alan

1957 births

Living people

Alumni of St John's College, Oxford

Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

Coxswains (rowing)

British drug policy reform activists

English libertarians

English people of Scottish descent

Gay politicians

Kennedy Scholarships

Harvard University alumni

Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

LGBT members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

English LGBT politicians

British LGBT rights activists

People educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood

People from Rickmansworth

Politics of Penistone

Presidents of the Oxford Union

Shell plc people

UK MPs 1992–1997

UK MPs 1997–2001

UK MPs 2001–2005

UK MPs 2005–2010

UK MPs 2010–2015

UK MPs 2015–2017

UK MPs 2017–2019

Politicians awarded knighthoods

Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Gay sportsmen

English LGBT sportspeople

LGBT rowers