Akragas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of

Theron, a member of the Emmenid family, made himself tyrant of Acragas around 488 BC. He formed an alliance with

Theron, a member of the Emmenid family, made himself tyrant of Acragas around 488 BC. He formed an alliance with

The period after the fall of the Emmenids is not well-known. An

The period after the fall of the Emmenids is not well-known. An

The other temples are much more fragmentary, having been toppled by earthquakes long ago and quarried for their stones. The largest by far is the Temple of Olympian Zeus, built to commemorate the Battle of Himera in 480 BC: it is believed to have been the largest Doric temple ever built. Although it was apparently used, it appears never to have been completed; construction was abandoned after the Carthaginian invasion of 406 BC.

The other temples are much more fragmentary, having been toppled by earthquakes long ago and quarried for their stones. The largest by far is the Temple of Olympian Zeus, built to commemorate the Battle of Himera in 480 BC: it is believed to have been the largest Doric temple ever built. Although it was apparently used, it appears never to have been completed; construction was abandoned after the Carthaginian invasion of 406 BC.

The remains of the temple were extensively quarried in the 18th century to build the jetties of

The remains of the temple were extensively quarried in the 18th century to build the jetties of

Many other Hellenistic and Roman sites can be found in and around the town. These include a pre-Hellenic cave sanctuary near a Temple of Demeter, over which the Church of San Biagio was built. A late Hellenistic funerary monument erroneously labelled the "Tomb of Theron" is situated just outside the sacred area, and a 1st-century AD '' heroon'' (heroic shrine) adjoins the 13th century Church of San Nicola a short distance to the north. A sizeable area of the Greco-Roman city has also been excavated, and several classical

Many other Hellenistic and Roman sites can be found in and around the town. These include a pre-Hellenic cave sanctuary near a Temple of Demeter, over which the Church of San Biagio was built. A late Hellenistic funerary monument erroneously labelled the "Tomb of Theron" is situated just outside the sacred area, and a 1st-century AD '' heroon'' (heroic shrine) adjoins the 13th century Church of San Nicola a short distance to the north. A sizeable area of the Greco-Roman city has also been excavated, and several classical

Yair Karelic's photos of the Valley of the TemplesAgrigento Old Town

{{Authority control Archaeological sites in Sicily Municipalities of the Province of Agrigento 580s BC Dorian colonies in Magna Graecia Colonies of Gela 6th-century BC establishments in Italy Populated places established in the 6th century BC

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento

The Province of Agrigento ( it, Provincia di Agrigento; scn, Pruvincia di Girgenti; officially ''Libero consorzio comunale di Agrigento'') is a province in the autonomous island region of Sicily in Italy, situated on its south-western coast. Follo ...

. It was one of the leading cities of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; the ...

during the golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

BC.

History

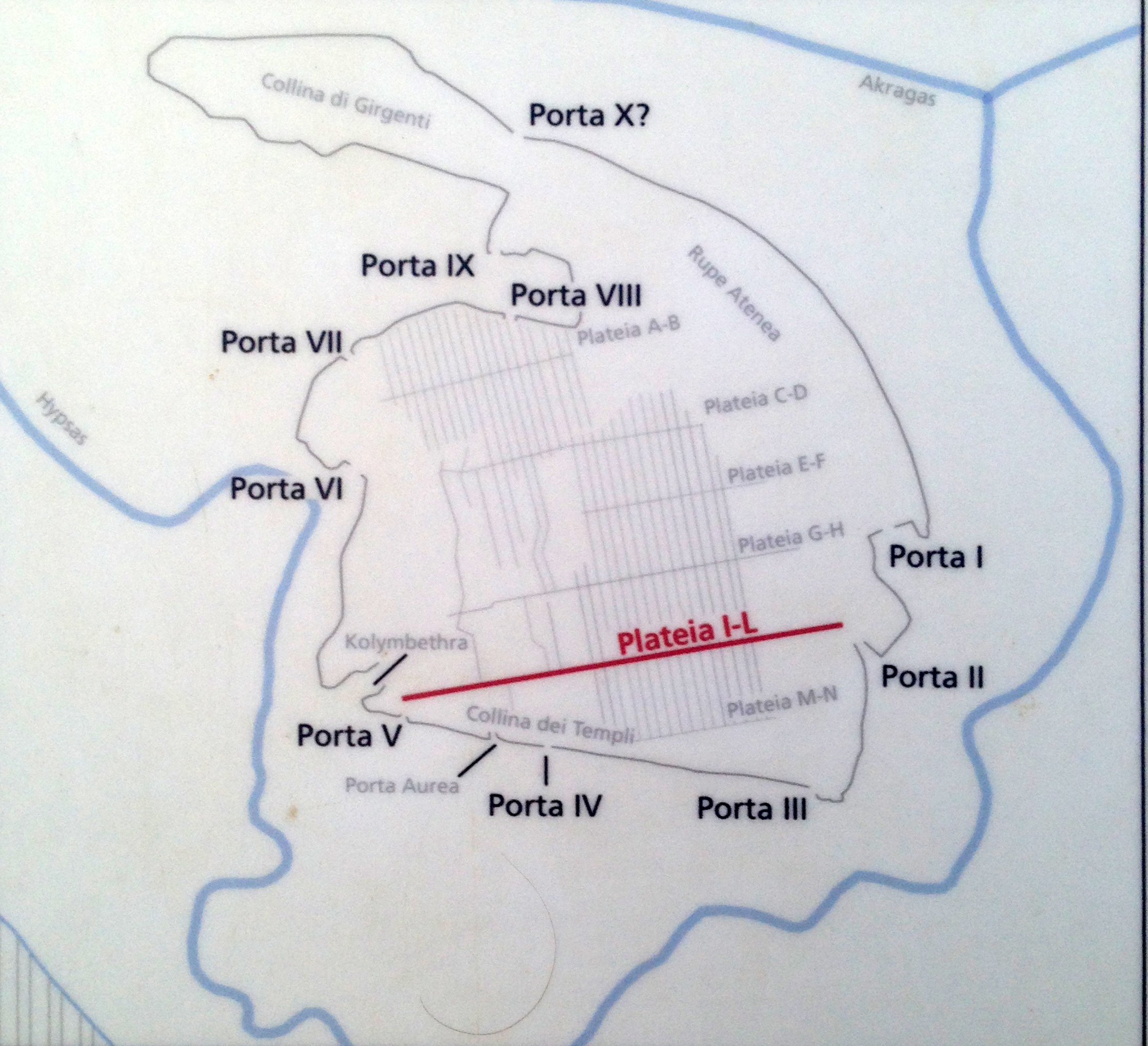

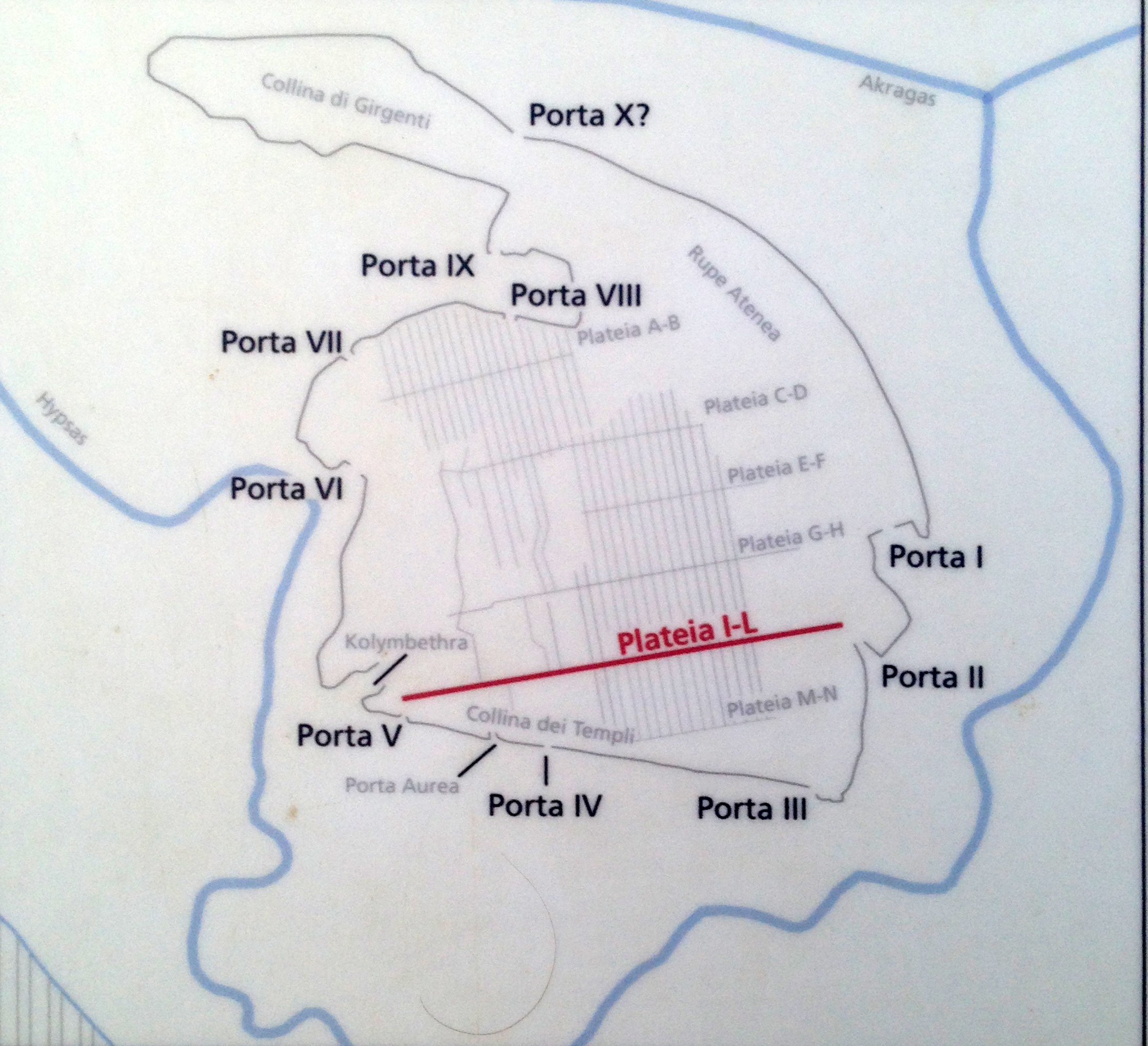

Akragas was founded on a plateau overlooking the sea, with two nearby rivers, the Hypsas and the Acragas, after which the settlement was originally named. A ridge, which offered a degree of natural fortification, links a hill to the north called Colle di Girgenti with another, called Rupe Atenea, to the east. According toThucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, it was founded around 582-580 BC by Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

colonists from Gela in eastern Sicily, with further colonists from Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

. The founders ( ''oikistai'') of the new city were Aristonous and Pystilus. It was the last of the major Greek colonies in Sicily to be founded.

Archaic period

The territory under Akragas's control expanded to comprise the whole area between the Platani and theSalso

The Salso ( Sicilian: ''Salsu''), also known as the Imera Meridionale (Greek: ; Latin Himera), is a river of Sicily. It rises in the Madonie Mountains (Latin: Nebrodes Mons; Sicilian: Munti Madunìi) and, traversing the provinces of Enna and Ca ...

, and reached deep into the Sicilian interior. Greek literary sources connect this expansion with military campaigns, but archaeological evidence indicates that this was a much longer term process which reached its peak only in the early fifth century BC. Most other Greek settlements in Sicily experienced similar territorial expansion in this period. Excavations at a range of sites in this region inhabited by the indigenous Sican people, such as Monte Sabbucina

Monte may refer to:

Places Argentina

* Argentine Monte, an ecoregion

* Monte Desert

* Monte Partido, a ''partido'' in Buenos Aires Province

Italy

* Monte Bregagno

* Monte Cassino

* Montecorvino (disambiguation)

* Montefalcione

Portugal

* Mont ...

, Gibil-Gabil, Vasallaggi, San Angelo Muxano, and Mussomeli, show signs of the adoption of Greek culture. It is disputed how much of this expansion was carried out by violence and how much by commerce and acculturation. The territorial expansion provided land for the Greek settlers to farm, native slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

to work these farms, and control of the overland route from Acragas to the city of Himera

Himera ( Greek: ), was a large and important ancient Greek city, situated on the north coast of Sicily at the mouth of the river of the same name (the modern Imera Settentrionale), between Panormus (modern Palermo) and Cephaloedium (modern Ce ...

on the northern coast of Sicily. This was the main land route from the Straits of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily (also known as Sicilian Strait, Sicilian Channel, Channel of Sicily, Sicilian Narrows and Pantelleria Channel; it, Canale di Sicilia or the Stretto di Sicilia; scn, Canali di Sicilia or Strittu di Sicilia, ar, مضيق ص ...

to the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

and Acragas' control of it was a key factor in its economic prosperity in the sixth and fifth centuries BC, which became proverbial. Famously, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, upon seeing the living standard of the inhabitants, was said to have remarked that "they build like they intend to live forever, yet eat like this is their last day." Perhaps as a result of this wealth, Acragas was one of the first communities in Sicily to begin minting its own coinage, around 520 BC.

Around 570 BC, the city came under the control of Phalaris

Phalaris ( el, Φάλαρις) was the tyrant of Akragas (now Agrigento) in Sicily, from approximately 570 to 554 BC.

History

Phalaris was renowned for his excessive cruelty. Among his alleged atrocities is cannibalism: he was said to have ...

, a semi-legendary figure, who was remembered as the archetypal tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

, said to have killed his enemies by burning them alive inside a bronze bull. In the ancient literary sources, he is linked with the military campaigns of territorial expansion, but this is probably anachronistic. He ruled until around 550 BC. The political history of Acragas in the second half of the sixth century is unknown, except for the names of two leaders, Alcamenes and Alcander. Acragas also expanded westwards over the course of the sixth century BC, leading to a rivalry with Selinus, the next Greek city to the west. The Selinuntines founded the city of Heraclea Minoa at the mouth of the Platani river, halfway between the two settlements, in the mid-sixth century BC, but the Acragantines conquered it around 500 BC.

Emmenid period

Theron, a member of the Emmenid family, made himself tyrant of Acragas around 488 BC. He formed an alliance with

Theron, a member of the Emmenid family, made himself tyrant of Acragas around 488 BC. He formed an alliance with Gelon

Gelon also known as Gelo ( Greek: Γέλων ''Gelon'', ''gen.'': Γέλωνος; died 478 BC), son of Deinomenes, was a Greek tyrant of the Sicilian cities Gela and Syracuse, and first of the Deinomenid rulers.

Early life

Gelon was the s ...

, tyrant of Gela and Syracuse. Around 483 BC, Theron invaded and conquered Himera, Acragas’ neighbour to the north. The tyrant of Himera, Terillus joined his son-in-law, Anaxilas of Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

, and the Selinuntines in calling on the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

to come and restore Terillus to power. The Carthaginians did invade in 480 BC, the first of the Greco-Punic Wars, but they were defeated by the combined forces of Theron and Gelon at the Battle of Himera. As a result, Acragas was affirmed in its control of the central portion of Sicily, an area of around 3,500 km2. A number of enormous construction projects were carried out in the Valle dei Templi at this time, including the Temple of Olympian Zeus, which was one of the largest Greek temples ever built, and the construction of a massive Kolymbethra reservoir. According to Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, they were built in commemoration of the Battle of Himera, using the prisoners captured in the war as slave labour. Archaeological evidence indicates that the boom in monumental construction actually began before the battle, but continued in the period after it. A major reconstruction of the city walls on a monumental scale also took place in this period. Theron sent teams to compete in the Olympic games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a multi ...

and other Panhellenic competitions in mainland Greece. Several poems by Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar ...

and Simonides

Simonides of Ceos (; grc-gre, Σιμωνίδης ὁ Κεῖος; c. 556–468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteeme ...

commemorated victories by Theron and other Acragantines, which provide insights into Acragantine identity and ideology at this time. Greek literary sources generally praise Theron as a good tyrant, but accuse his son Thrasydaeus

Thrasydaeus ( grc, Θρασυδαῖος), tyrant of Agrigentum, was the son and successor of Theron. Already during his father's lifetime he had been appointed to the government of Himera, where, by his violent and arbitrary conduct, he alienated ...

, who succeeded him in 472 BC, of violence and oppression. Shortly after Theron's death, Hiero I of Syracuse

Hieron I ( el, Ἱέρων Α΄; usually Latinized Hiero) was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

Life

During hi ...

(brother and successor of Gelon) invaded Acragas and overthrew Thrasydaeus. The literary sources say that Acragas then became a democracy, but in practice it seems to have been dominated by the civic aristocracy.

Classical and Hellenistic periods

oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

group called "the thousand" was in power for a few years in the mid-fifth century BC, but was overthrown - the literary tradition gives the philosopher Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

a decisive role in this revolution, but some modern scholars have doubted this. In 451 BC, Ducetius

Ducetius ( grc, Δουκέτιος) (died 440 BCE) was a Hellenized leader of the Sicels and founder of a united Sicilian state and numerous cities.LiviusDucetius of Sicily Retrieved on 25 April 2006. It is thought he may have been born around ...

, leader of a Sicel state opposed to the expansion of Syracuse and other Greeks into the interior of Sicily invaded Acragantine territory, conquering an outpost called Motyum. Ducetius was defeated in 450, but the Syracusan decision to let Ducetius go outraged the Acragantines and they went to war with Syracuse. They were defeated in a battle on the Salso river, which left Syracuse the pre-eminent power in eastern Sicily. The defeat was serious enough that Acragas ceased to mint coinage for a number of years.

Ancient sources considered Acragas to be a very large city at this time. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

says that the population was 200,000 people, of which 20,000 were citizens. Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sour ...

put the population at an incredible 800,000. Some modern scholars have accepted Diodorus' numbers, but they seem to be far too high. Jos de Waele suggests a population of 16,000-18,000 citizens, while Franco de Angelis estimates a total population of around 30,000-40,000.

When Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

undertook the Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a de ...

against Syracuse from 415-413 BC, Acragas remained neutral. However, it was sacked by the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

in 406 BC. Acragas never fully recovered its former status, though it revived following the invasion of Timoleon

Timoleon ( Greek: Τιμολέων), son of Timodemus, of Corinth (c. 411–337 BC) was a Greek statesman and general.

As a brilliant general, a champion of Greece against Carthage, and a fighter against despotism, he is closely connected ...

in the late fourth century onwards and large-scale construction took place in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

. During the early 3rd century BC, a tyrant called Phintias declared himself king in Akragas, also controlling a variety of other cities. His kingdom was however not long-lived.

Roman period

The city was disputed between the Romans and the Carthaginians during theFirst Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

. The Romans laid siege to the city in 262 BC and captured it after defeating a Carthaginian relief force in 261 BC and sold the population into slavery. Although the Carthaginians recaptured the city in 255 BC the final peace settlement gave Punic Sicily and with it Akragas to Rome. It suffered badly during the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

(218–201 BC) when both Rome and Carthage fought to control it. The Romans eventually captured Akragas in 210 BC and renamed it ''Agrigentum'', although it remained a largely Greek-speaking community for centuries thereafter. It became prosperous again under Roman rule and its inhabitants received full Roman citizenship following the death of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

in 44 BC.

Middle Ages

After thefall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its va ...

, the city successively passed into the hands of the Vandalic Kingdom, the Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great killed and replaced Odoacer, ...

of Italy and then the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. During this period the inhabitants of Agrigentum largely abandoned the lower parts of the city and moved to the former acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

, at the top of the hill. The reasons for this move are unclear but were probably related to the destructive coastal raids of the Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia ...

and other peoples around this time. In 828 AD the Saracens captured the diminished remnant of the city; the Arabic form of its name became () or ().

Following the Norman conquest of Sicily, the city changed its name to the Norman version ''Girgenti''. In 1087, Norman Count Roger I established a Latin bishopric in the city. Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

built the Castello di Agrigento to control the area. The population declined during much of the medieval period but revived somewhat after the 18th century.

Modern period

In 1860, as in the rest of Sicily, the inhabitants supported the arrival ofGiuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, pa ...

during the Expedition of the Thousand (one of the most dramatic events of the Unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

) which marked the end of Bourbon rule. In 1927, Benito Mussolini through the "Decree Law n. 159, July 12, 1927" introduced the current Italianized version of the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

name. The decision remains controversial as a symbol of Fascism and the eradication of local history. Following the suggestion of Andrea Camilleri

Andrea Calogero Camilleri (; 6 September 1925 – 17 July 2019) was an Italian writer.

Biography

Originally from Porto Empedocle, Girgenti, Sicily, Camilleri began university studies in the Faculty of Literature at the University of Palermo, b ...

, a Sicilian writer of Agrigentine origin, the historic city centre was renamed to the Sicilian name "Girgenti" in 2016. The city suffered a number of destructive bombing raids during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Economy

Agrigento is a major tourist centre due to its extraordinarily rich archaeological legacy. It also serves as an agricultural centre for the surrounding region.Sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

and potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form.

were mined locally from Minoan times until the 1970s, and were exported worldwide from the nearby harbour of Porto Empedocle

Porto Empedocle ( scn, 'a Marina) is a town and '' comune'' in Italy on the coast of the Strait of Sicily, administratively part of the province of Agrigento. It was named after Empedocles, a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a citizen of t ...

(named after the philosopher Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

, who lived in ancient Akragas). In 2010, the unemployment rate

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refere ...

in Agrigento was 19.2%, almost twice the national average.

Main sights

Ancient Akragas covers a huge area—much of which is still unexcavated today—but is exemplified by the famous ''Valle dei Templi'' ("Valley of the Temples", a misnomer, as it is a ridge, rather than a valley). This comprises a large sacred area on the south side of the ancient city where seven monumental Greek temples in theDoric style

The Doric order was one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognized by the simple circular capitals at the top of col ...

were constructed during the 6th and 5th centuries BC. Now excavated and partially restored, they constitute some of the largest and best-preserved ancient Greek buildings outside of Greece itself. They are listed as a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

.

The best-preserved of the temples are two very similar buildings traditionally attributed to the goddesses Hera Lacinia and Concordia (though archaeologists believe this attribution to be incorrect). The latter temple is remarkably intact, due to its having been converted into a Christian church in 597 AD. Both were constructed to a peripteral hexastyle

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

design. The area around the Temple of Concordia was later re-used by early Christians as a catacomb

Catacombs are man-made subterranean passageways for religious practice. Any chamber used as a burial place is a catacomb, although the word is most commonly associated with the Roman Empire.

Etymology and history

The first place to be referred ...

, with tombs hewn out of the rocky cliffs and outcrops.

The remains of the temple were extensively quarried in the 18th century to build the jetties of

The remains of the temple were extensively quarried in the 18th century to build the jetties of Porto Empedocle

Porto Empedocle ( scn, 'a Marina) is a town and '' comune'' in Italy on the coast of the Strait of Sicily, administratively part of the province of Agrigento. It was named after Empedocles, a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a citizen of t ...

. Temples dedicated to Hephaestus

Hephaestus (; eight spellings; grc-gre, Ἥφαιστος, Hḗphaistos) is the Greek god of blacksmiths, metalworking, carpenters, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire (compare, however, with Hestia), and volcanoes.Walter B ...

, Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptiv ...

and Asclepius

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Greek religion and mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis, or Arsinoe, or of Apollo alone. Asclepius represen ...

were also constructed in the sacred area, which includes a sanctuary of Demeter

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Demeter (; Attic Greek, Attic: ''Dēmḗtēr'' ; Doric Greek, Doric: ''Dāmā́tēr'') is the Twelve Olympians, Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over crops, ...

and Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone ( ; gr, Περσεφόνη, Persephónē), also called Kore or Cora ( ; gr, Κόρη, Kórē, the maiden), is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld aft ...

(formerly known as the Temple of Castor and Pollux); the marks of the fires set by the Carthaginians in 406 BC can still be seen on the sanctuary's stones.

Many other Hellenistic and Roman sites can be found in and around the town. These include a pre-Hellenic cave sanctuary near a Temple of Demeter, over which the Church of San Biagio was built. A late Hellenistic funerary monument erroneously labelled the "Tomb of Theron" is situated just outside the sacred area, and a 1st-century AD '' heroon'' (heroic shrine) adjoins the 13th century Church of San Nicola a short distance to the north. A sizeable area of the Greco-Roman city has also been excavated, and several classical

Many other Hellenistic and Roman sites can be found in and around the town. These include a pre-Hellenic cave sanctuary near a Temple of Demeter, over which the Church of San Biagio was built. A late Hellenistic funerary monument erroneously labelled the "Tomb of Theron" is situated just outside the sacred area, and a 1st-century AD '' heroon'' (heroic shrine) adjoins the 13th century Church of San Nicola a short distance to the north. A sizeable area of the Greco-Roman city has also been excavated, and several classical necropoleis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually i ...

and quarries are still extant.

Much of present-day Agrigento is modern but it still retains a number of medieval and Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

buildings. These include the 14th century cathedral and the 13th century Church of Santa Maria dei Greci ("St. Mary of the Greeks"), again standing on the site of an ancient Greek temple (hence the name). The town also has a notable archaeological museum displaying finds from the ancient city.

People

*Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

(5th Century BC), the Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

, was a citizen of ancient ''Akragas''.

* Tellias ( grc, Τελλίας) of Akragas, described in ancient sources as a hospitable man; when 500 horsemen were billeted with him during the winter, he gave each a tunic and cloak.

* Karkinos ( grc, Καρκίνος) of Akragas, a tragedian

* Tigellinus (born c10 AD), a Prefect of the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

and infamous associate of the Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

, belonged to a family of Greek descent in Agrigento - although he may have been born in Scyllaceum in Southern Italy, where his father is supposed to have lived in exile.

* Paolo Girgenti

Paolo Girgenti (1767/69 – 1819) was an Italian painter of the late 18th and early 19th-centuries, active in Naples.

He was born in Agrigento, Sicily, known in Sicilian language as ''Girgenti''. He studied, along with a Giuseppe Camerata from S ...

(1767–1815), a painter active in Naples who served as president of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli

The Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli (Naples Academy of Fine Arts) is a university-level art school in Naples. In the past it has been known as the Reale Istituto di Belle Arti and the Reale Accademia di Belle Arti. Founded by King Charles VII ...

, was born in Agrigento.

* Luigi Pirandello

Luigi Pirandello (; 28 June 1867 – 10 December 1936) was an Italian dramatist, novelist, poet, and short story writer whose greatest contributions were his plays. He was awarded the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature for "his almost magical power ...

(1867-1936), dramatist and Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

winner for literature, was born at contrada

A (plural: ) is a subdivision (of various types) of Italian city, now unofficial. Depending on the case, a will be a ''località'', a ''rione'', a ''quartiere'' (''terziere'', etc.), a '' borgo'', or even a suburb. The best-known are the 1 ...

''u Càvusu'' in Agrigento.

* Giovanni Leone

Giovanni Leone (; 3 November 1908 – 9 November 2001) was an Italian politician, jurist, and university professor. A founding member of the Christian Democracy (DC), Leone served as the President of Italy from December 1971 until June 1978. ...

(b. 1967), an Italian geophysicist and volcanologist, was born in Agrigento.

* Vinnie Paz (b. 1977), the Italian-American rapper and lyricist behind Philadelphia underground hip-hop group Jedi Mind Tricks.

* Larry Page

Lawrence Edward Page (born March 26, 1973) is an American business magnate, computer scientist and internet entrepreneur. He is best known for co-founding Google with Sergey Brin.

Page was the chief executive officer of Google from 1997 unti ...

(b. 1973), co-founder of Google

Google LLC () is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company focusing on Search Engine, search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, software, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, ar ...

, became an honorary citizen of Agrigento on August 4, 2017.

Twin towns – sister cities

Agrigento is twinned with: * Perm, Russia *Tampa

Tampa () is a city on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The city's borders include the north shore of Tampa Bay and the east shore of Old Tampa Bay. Tampa is the largest city in the Tampa Bay area and the seat of Hillsborough C ...

, United States

* Valenciennes

Valenciennes (, also , , ; nl, label=also Dutch, Valencijn; pcd, Valincyinnes or ; la, Valentianae) is a commune in the Nord department, Hauts-de-France, France.

It lies on the Scheldt () river. Although the city and region experienced a ...

, France

See also

* Siege of Akragas (406 BC) * Agrigentum inscription * Battle of Agrigentum (456) * List of mayors of AgrigentoReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * * *External links

Yair Karelic's photos of the Valley of the Temples

{{Authority control Archaeological sites in Sicily Municipalities of the Province of Agrigento 580s BC Dorian colonies in Magna Graecia Colonies of Gela 6th-century BC establishments in Italy Populated places established in the 6th century BC