Aircraft catapult on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on

Many naval vessels apart from aircraft carriers carried float planes, seaplanes or amphibians for reconnaissance and spotting. They were catapult-launched and landed on the sea alongside for recovery by crane. Additionally, the concept of submarine aircraft carriers was developed by multiple nations during the interwar period, and through until WW2 and beyond, wherein a submarine would launch a small number of floatplanes for offensive operations or artillery spotting, to be recovered by the submarine once the aircraft has landed. The first launch off a

Many naval vessels apart from aircraft carriers carried float planes, seaplanes or amphibians for reconnaissance and spotting. They were catapult-launched and landed on the sea alongside for recovery by crane. Additionally, the concept of submarine aircraft carriers was developed by multiple nations during the interwar period, and through until WW2 and beyond, wherein a submarine would launch a small number of floatplanes for offensive operations or artillery spotting, to be recovered by the submarine once the aircraft has landed. The first launch off a

The protruding angled ramps (Van Velm Bridle Arresters or horns) at the catapult ends on some aircraft carriers were used to catch the bridles (connectors between the catapult shuttle and aircraft fuselage) for reuse. There were small ropes that would attach the bridle to the shuttle, which continued down the angled horn to pull the bridle down and away from the aircraft to keep it from damaging the underbelly. The bridle would then be caught by nets aside the horn. Bridles have not been used on U.S. aircraft since the end of the

The protruding angled ramps (Van Velm Bridle Arresters or horns) at the catapult ends on some aircraft carriers were used to catch the bridles (connectors between the catapult shuttle and aircraft fuselage) for reuse. There were small ropes that would attach the bridle to the shuttle, which continued down the angled horn to pull the bridle down and away from the aircraft to keep it from damaging the underbelly. The bridle would then be caught by nets aside the horn. Bridles have not been used on U.S. aircraft since the end of the

The size and manpower requirements of steam catapults place limits on their capabilities. A newer approach is the electromagnetic catapult, such as Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) developed by General Atomics. Electromagnetic catapults place less stress on the aircraft and offer more control during the launch by allowing gradual and continual acceleration. Electromagnetic catapults are also expected to require significantly less maintenance through the use of solid state components.

Linear induction motors have been experimented with before, such as Westinghouse's Electropult system in 1945. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, navies again started experimenting with catapults powered by linear induction motors and

The size and manpower requirements of steam catapults place limits on their capabilities. A newer approach is the electromagnetic catapult, such as Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) developed by General Atomics. Electromagnetic catapults place less stress on the aircraft and offer more control during the launch by allowing gradual and continual acceleration. Electromagnetic catapults are also expected to require significantly less maintenance through the use of solid state components.

Linear induction motors have been experimented with before, such as Westinghouse's Electropult system in 1945. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, navies again started experimenting with catapults powered by linear induction motors and

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s, as a form of assisted take off

In aviation, assisted takeoff is any system for helping aircraft to get into the air (as opposed to strictly under its own power). The reason it might be needed is due to the aircraft's weight exceeding the normal maximum takeoff weight, insuf ...

.

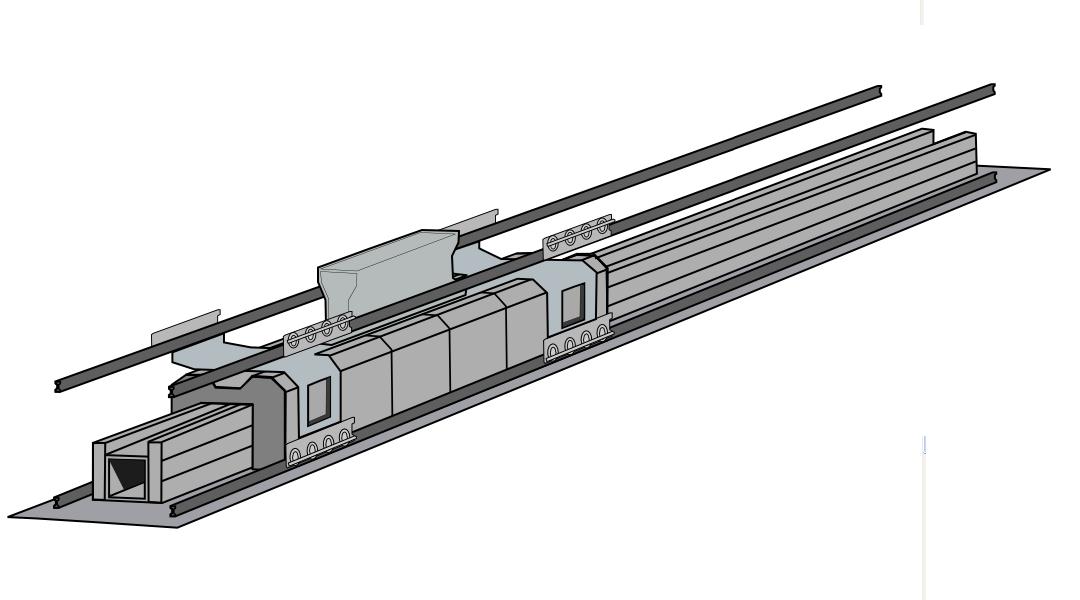

In the form used on aircraft carriers the catapult consists of a track, or slot, built into the flight deck, below which is a large piston or ''shuttle'' that is attached through the track to the nose gear

A nose is a protuberance in vertebrates that houses the nostrils, or nares, which receive and expel air for respiration alongside the mouth. Behind the nose are the olfactory mucosa and the sinuses. Behind the nasal cavity, air next passes thr ...

of the aircraft, or in some cases a wire rope

Steel wire rope (right hand lang lay)

Wire rope is several strands of metal wire twisted into a helix forming a composite

'' rope'', in a pattern known as ''laid rope''. Larger diameter wire rope consists of multiple strands of such laid rope in ...

, called a catapult bridle, is attached to the aircraft and the catapult shuttle. Other forms have been used historically, such as mounting a launching cart holding a seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

on a long girder-built structure mounted on the deck of a warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster ...

or merchant vessel

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

, but most catapults share a similar sliding track concept.

Different means have been used to propel the catapult, such as weight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force acting on the object due to gravity.

Some standard textbooks define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others define weight as a scalar qua ...

and derrick, gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

, flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device which uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy; a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, as ...

, air pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars ...

, hydraulic

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counte ...

, and steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tra ...

, and solid fuel rocket boosters. The U.S. Navy is developing the use of Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch Systems with the construction of the s.

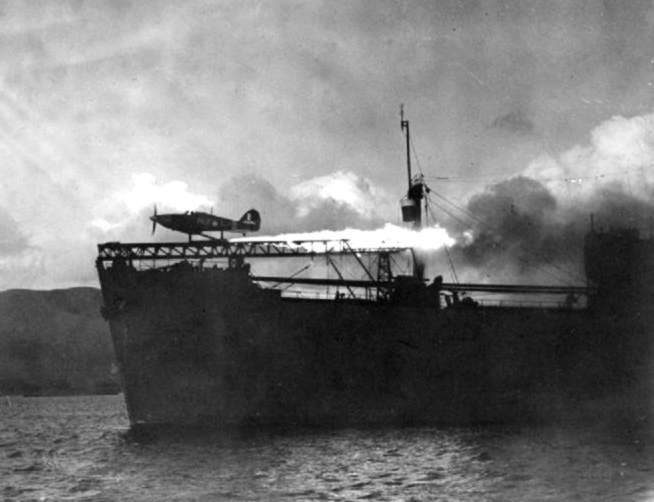

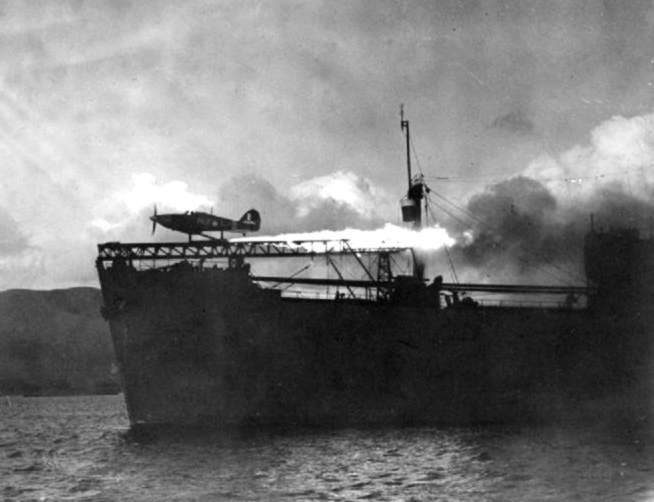

Historically it was most common for seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

s to be catapulted, allowing them to land on the water near the vessel and be hoisted on board, although in WWII (before the advent of the escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

) conventional fighter planes (notably the Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness b ...

) would sometimes be catapulted from " catapult-equipped merchant" (CAM) vessels to drive off enemy aircraft, forcing the pilot to either divert to a land based airstrip, or to jump out by parachute or ditch in the water near the convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

and wait for rescue.

History

First recorded flight using a catapult

Aviation pioneer and Smithsonian SecretarySamuel Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley (August 22, 1834 – February 27, 1906) was an American aviation pioneer, astronomer and physicist who invented the bolometer. He was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a professor of astronomy ...

used a spring-operated catapult to launch his successful flying models and his failed Aerodrome

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publi ...

of 1903. Likewise the Wright Brothers beginning in 1904 used a weight and derrick styled catapult to assist their early aircraft with a takeoff in a limited distance.

On 31 July 1912, Theodore Gordon Ellyson became the first person to be launched from a U.S. Navy catapult system. The Navy had been perfecting a compressed-air catapult system and mounted it on the Santee Dock in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

. The first attempt nearly killed Lieutenant Ellyson when the plane left the ramp with its nose pointing upward and it caught a crosswind, pushing the plane into the water. Ellyson was able to escape from the wreckage unhurt. On 12 November 1912, Lt. Ellyson made history as the Navy's first successful catapult launch, from a stationary coal barge. On 5 November 1915, Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin made the first catapult launch from a ship underway.

Application timeline

Interwar and World War II

The US Navy experimented with other power sources and models, including catapults that utilized gunpowder and flywheel variations. On 14 December 1924, a Martin MO-1 observation plane flown by Lt. L. C. Hayden was launched from using a catapult powered by gunpowder. Following this launch, this method was used aboard bothcruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several ...

s and battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

s.

By 1929, the German ocean liners ''SS Bremen'' and ''Europa'' had been fitted with compressed-air catapults designed by the Heinkel

Heinkel Flugzeugwerke () was a German aircraft manufacturing company founded by and named after Ernst Heinkel. It is noted for producing bomber aircraft for the Luftwaffe in World War II and for important contributions to high-speed flight, with ...

aviation firm of Rostock, with further work with catapult air mail across the South Atlantic Ocean, being undertaken during the first half of the 1930s, with Dornier ''Wal'' twin-engined flying boats.

Up to and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, most catapults on aircraft carriers were hydraulic. United States Navy catapults on surface warships, however, were operated with explosive charges similar to those used for 5" guns. Some carriers were completed before and during World War II with catapults on the hangar deck that fired athwartships, but they were unpopular because of their short run, low clearance of the hangar decks, inability to add the ship's forward speed to the aircraft's airspeed for takeoff, and lower clearance from the water (conditions which afforded pilots far less margin for error in the first moments of flight). They were mostly used for experimental purposes, and their use was entirely discontinued during the latter half of the war. Many naval vessels apart from aircraft carriers carried float planes, seaplanes or amphibians for reconnaissance and spotting. They were catapult-launched and landed on the sea alongside for recovery by crane. Additionally, the concept of submarine aircraft carriers was developed by multiple nations during the interwar period, and through until WW2 and beyond, wherein a submarine would launch a small number of floatplanes for offensive operations or artillery spotting, to be recovered by the submarine once the aircraft has landed. The first launch off a

Many naval vessels apart from aircraft carriers carried float planes, seaplanes or amphibians for reconnaissance and spotting. They were catapult-launched and landed on the sea alongside for recovery by crane. Additionally, the concept of submarine aircraft carriers was developed by multiple nations during the interwar period, and through until WW2 and beyond, wherein a submarine would launch a small number of floatplanes for offensive operations or artillery spotting, to be recovered by the submarine once the aircraft has landed. The first launch off a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

battlecruiser was from on 8 March 1918. Subsequently, many Royal Navy ships carried a catapult and from one to four aircraft; battleships or battlecruisers like carried four aircraft and carried two, while smaller warships like the cruiser carried one. The aircraft carried were the Fairey Seafox or Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus (originally designated the Supermarine Seagull V) was a British single-engine amphibious biplane reconnaissance aircraft designed by R. J. Mitchell and manufactured by Supermarine at Woolston, Southampton.

The Walrus f ...

. Some like did not use a catapult, and the aircraft was lowered onto the sea for takeoff. Some had their aircraft and catapult removed during World War II e.g. , or before ().

During World War II a number of ships were fitted with rocket-driven catapults, first the fighter catapult ship

Fighter catapult ships also known as Catapult Armed Ships were an attempt by the Royal Navy to provide air cover at sea. Five ships were acquired and commissioned as Naval vessels early in the Second World War, and these were used to accompany con ...

s of the Royal Navy, then armed merchantmen known as CAM ships from "catapult armed merchantmen." These were used for convoy escort duties to drive off enemy reconnaissance bombers. CAM ships carried a Hawker Sea Hurricane 1A, dubbed a "Hurricat" or "Catafighter", and the pilot bailed out unless he could fly to land.

While imprisoned in Colditz Castle

Castle Colditz (or ''Schloss Colditz'' in German) is a Renaissance castle in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony in Germany. The castle is between the towns of Hartha and Grimma on a hill spur over the ...

during the war, British prisoners of war planned an escape attempt using a falling bathtub

A bathtub, also known simply as a bath or tub, is a container for holding water in which a person or animal may bathe. Most modern bathtubs are made of thermoformed acrylic, porcelain-enameled steel or cast iron, or fiberglass-reinforced pol ...

full of heavy rocks and stones as the motive power for a catapult to be used for launching the Colditz Cock glider from the roof of the castle.

Ground-launched V-1s were typically propelled up an inclined launch ramp by an apparatus known as a ''Dampferzeuger'' ("steam generator").

Steam catapult

Following World War II, the Royal Navy was developing a new catapult system for their fleet of carriers. Commander Colin C. Mitchell, RNV, recommended a steam-based system as an effective and efficient means to launch the next generation of naval aircraft. Trials on , flown by pilots such asEric "Winkle" Brown

Captain Eric Melrose "Winkle" Brown, CBE, DSC, AFC, Hon FRAeS, RN (21 January 1919 – 21 February 2016) was a British Royal Navy officer and test pilot who flew 487 types of aircraft, more than anyone else in history.

Brown holds the world ...

, from 1950 showed its effectiveness. Navies introduced steam catapults, capable of launching the heavier jet fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

, in the mid-1950s. Powder-driven catapults were also contemplated, and would have been powerful enough, but would also have introduced far greater stresses on the airframes and might have been unsuitable for long use.

At launch, a release bar holds the aircraft in place as steam pressure builds up, then breaks (or "releases"; older models used a pin that sheared), freeing the piston to pull the aircraft along the deck at high speed. Within about two to four seconds, aircraft velocity by the action of the catapult plus apparent wind speed (ship's speed plus or minus "natural" wind) is sufficient to allow an aircraft to fly away, even after losing one engine.

Nations that have retained large aircraft carriers, i.e., the United States Navy and the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, are still using a CATOBAR

CATOBAR ("Catapult Assisted Take-Off But Arrested Recovery" or "Catapult Assisted Take-Off Barrier Arrested Recovery") is a system used for the launch and recovery of aircraft from the deck of an aircraft carrier. Under this technique, aircraft ...

(Catapult Assisted Take Off But Arrested Recovery) configuration. U.S. Navy tactical aircraft use catapults to launch with a heavier warload than would otherwise be possible. Larger planes, such as the E-2 Hawkeye

The Northrop Grumman E-2 Hawkeye is an American all-weather, carrier-capable tactical airborne early warning (AEW) aircraft. This twin-turboprop aircraft was designed and developed during the late 1950s and early 1960s by the Grumman Aircraft ...

and S-3 Viking, require a catapult shot, since their thrust-to-weight ratio is too low for a conventional rolling takeoff on a carrier deck.

Steam catapults types

Presently or at one time operated by the U.S. and French navies include:Bridle catchers

The protruding angled ramps (Van Velm Bridle Arresters or horns) at the catapult ends on some aircraft carriers were used to catch the bridles (connectors between the catapult shuttle and aircraft fuselage) for reuse. There were small ropes that would attach the bridle to the shuttle, which continued down the angled horn to pull the bridle down and away from the aircraft to keep it from damaging the underbelly. The bridle would then be caught by nets aside the horn. Bridles have not been used on U.S. aircraft since the end of the

The protruding angled ramps (Van Velm Bridle Arresters or horns) at the catapult ends on some aircraft carriers were used to catch the bridles (connectors between the catapult shuttle and aircraft fuselage) for reuse. There were small ropes that would attach the bridle to the shuttle, which continued down the angled horn to pull the bridle down and away from the aircraft to keep it from damaging the underbelly. The bridle would then be caught by nets aside the horn. Bridles have not been used on U.S. aircraft since the end of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, and all U.S. Navy carriers commissioned since then have not had the ramps. The last U.S. carrier commissioned with a bridle catcher was USS ''Carl Vinson''; starting with USS ''Theodore Roosevelt'' the ramps were deleted. During Refueling and Complex Overhaul

In the United States Navy, Refueling and Overhaul (ROH) refers to a lengthy refitting process or procedure performed on nuclear-powered naval ships, which involves replacement of expended nuclear fuel with new fuel and a general maintenance f ...

refits in the late 1990s–early 2000s, the bridle catchers were removed from the first three s. USS ''Enterprise'' was the last U.S. Navy operational carrier with the ramps still attached before her inactivation in 2012.

Like her American counterparts today, the French aircraft carrier ''Charles De Gaulle'' is not equipped with bridle catchers because the modern aircraft operated on board use the same launch systems as in US Navy. Because of this mutual interoperability, American aircraft are also capable of being catapulted from and landing on ''Charles De Gaulle'', and conversely, French naval aircraft can use the US Navy carriers' catapults. At the time when the Super Étendard was operated on board of the ''Charles de Gaulle'', its bridles were used only once, as they were never recovered by bridle catchers.

The carriers and were also equipped with bridle catchers, not for the Super Étendards but only to catch and recover the Vought F-8 Crusader

The Vought F-8 Crusader (originally F8U) is a single-engine, supersonic, carrier-based air superiority jet aircraft built by Vought for the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps (replacing the Vought F7U Cutlass), and for the Fren ...

's bridles.

Electromagnetic catapult

electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in ...

s. Electromagnetic catapult would be more energy efficient on nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and would alleviate some of the dangers posed by using pressurized steam. On gas-turbine powered ships, an electromagnetic catapult would eliminate the need for a separate steam boiler for generating catapult steam. The U.S. Navy's s and PLA Navy’s Type 003 aircraft carrier included electromagnetic catapults in their design.

Civilian use

From 1929, the GermanNorddeutscher Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of ...

-liners and were fitted with compressed air-driven catapults designed by the ''Heinkel Flugzeugwerke

Heinkel Flugzeugwerke () was a German aircraft manufacturing company founded by and named after Ernst Heinkel. It is noted for producing bomber aircraft for the Luftwaffe in World War II and for important contributions to high-speed flight, with ...

'' to launch mail-planes. These ships served the route between Germany and the United States. The aircraft, carrying mail–bags, would be launched as a mail tender

A mail tender is a small steamboat used to carry mail. As a tender it only carries mail for short distances between ship and shore, ferrying it to and from a large mail steamer.

The use of tenders for loading passengers and their luggage was we ...

while the ship was still many hundreds of miles from its destination, thus speeding mail delivery by about a day. Initially, Heinkel He 12 aircraft were used before they were replaced by Junkers Ju 46, which were in turn replaced by the Vought V-85G.

German airline Lufthansa

Deutsche Lufthansa AG (), commonly shortened to Lufthansa, is the flag carrier of Germany. When combined with its subsidiaries, it is the second- largest airline in Europe in terms of passengers carried. Lufthansa is one of the five founding ...

subsequently used dedicated catapult ships , , ''Ostmark'' and ''Friesenland'' to launch larger Dornier Do J

The Dornier Do J ''Wal'' ("whale") is a twin-engine German flying boat of the 1920s designed by ''Dornier Flugzeugwerke''. The Do J was designated the Do 16 by the Reich Air Ministry (''RLM'') under its aircraft designation system of 1933.

De ...

''Wal'' (whale), Dornier Do 18 and Dornier Do 26

The Dornier Do 26 was an all-metal gull-winged flying boat produced before and during World War II by ''Dornier Flugzeugwerke'' of Germany. It was operated by a crew of four and was intended to carry a payload of 500 kg (1,100 lb) o ...

flying boats

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusel ...

on the South Atlantic airmail service from Stuttgart, Germany to Natal, Brazil. On route proving flights in 1933, and a scheduled service beginning in February 1934, ''Wals'' flew the trans-ocean stage of the route, between Bathurst, the Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

in West Africa and Fernando de Noronha

Fernando de Noronha () is an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, part of the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, and located off the Brazilian coast. It consists of 21 islands and islets, extending over an area of . Only the eponymous main island is in ...

, an island group off South America. At first, there was a refueling stop in mid-ocean. The flying boat would land on the open sea, be winched aboard by a crane, refueled, and then launched by catapult back into the air. However, landing on the big ocean swells tended to damage the hull of the flying boats. From September 1934, ''Lufthansa'' had a support ship at each end of the trans-ocean stage, providing radio navigation signals and catapult launchings after carrying aircraft out to sea overnight. From April 1935 the ''Wals'' were launched directly offshore, and flew the entire distance across the ocean. This was possible as the flying boats could carry more fuel when they did not have to take off from the water under their own power, and cut the time it took for mail to get from Germany to Brazil from four days down to three.

From 1936 to 1938, tests including the Blohm & Voss Ha 139 flying boat were conducted on the North Atlantic route to New York. ''Schwabenland'' was also used in an Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

expedition in 1938/39 with the main purpose of finding an area for a German whaling station, in which catapult-launched ''Wals'' surveyed a territory subsequently claimed by Germany as New Swabia. All of ''Lufthansa'' catapult ships were taken over by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

in 1939 and used as seaplane tender

A seaplane tender is a boat or ship that supports the operation of seaplanes. Some of these vessels, known as seaplane carriers, could not only carry seaplanes but also provided all the facilities needed for their operation; these ships are rega ...

s in World War II along with three catapult ships built for the military.

After World War II, Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus (originally designated the Supermarine Seagull V) was a British single-engine amphibious biplane reconnaissance aircraft designed by R. J. Mitchell and manufactured by Supermarine at Woolston, Southampton.

The Walrus f ...

amphibian aircraft were also briefly operated by a British whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

company, United Whalers. Operating in the Antarctic, they were launched from the factory ship FF ''Balaena'', which had been equipped with an ex-navy aircraft catapult.London 2003, p. 213.

Alternatives to catapults

The Chinese, Indian, and Russian navies operate conventional aircraft from STOBAR aircraft carriers (Short Take-Off But Arrested Landing). Instead of a catapult, they use a ski jump to assist aircraft in taking off with a positive rate of climb. Carrier aircraft such as the J-15,Mig-29K

The Mikoyan MiG-29K (russian: Микоян МиГ-29K; NATO reporting name: Fulcrum-D) is a Russian all-weather carrier-based multirole fighter aircraft developed by the Mikoyan Design Bureau. The MiG-29K was developed in the late 1980s from ...

, and Su-33 rely on their own engines to accelerate to flight speed. As a result, they must take off with a reduced load of fuel and armaments.

All other navies with aircraft carriers operate STOVL aircraft, such as the F-35B Lightning II, the Sea Harrier, and the AV-8B Harrier II

The McDonnell Douglas (now Boeing) AV-8B Harrier II is a single-engine ground-attack aircraft that constitutes the second generation of the Harrier family, capable of vertical or short takeoff and landing (V/STOL). The aircraft is primari ...

. These aircraft can take off vertically with a light load, or use a ski jump to assist a rolling takeoff with a heavy load. STOVL carriers are less expensive and generally smaller in size compared to CATOBAR carriers.

See also

* Ground carriage *Jet blast deflector

A jet blast deflector (JBD) or blast fence is a safety device that redirects the high energy exhaust from a jet engine to prevent damage and injury. The structure must be strong enough to withstand heat and high speed air streams as well as dust ...

* Modern US Navy carrier operations

* Naval aviation

*

References

Bibliography

* London, Peter. ''British Flying Boats''. Stoud, UK: Sutton Publishers Ltd., 2003. . * . {{DEFAULTSORT:Aircraft CatapultCatapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stor ...

Catapult