The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the

early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the

Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid- 15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the introduction of nava ...

, approximately from the

15th century

The 15th century was the century which spans the Julian dates from 1 January 1401 ( MCDI) to 31 December 1500 ( MD).

In Europe, the 15th century includes parts of the Late Middle Ages, the Early Renaissance, and the early modern period.

...

to the

17th century

The 17th century lasted from January 1, 1601 ( MDCI), to December 31, 1700 ( MDCC). It falls into the early modern period of Europe and in that continent (whose impact on the world was increasing) was characterized by the Baroque cultural movemen ...

in

European history, during which

seafaring Europeans explored and colonized regions across the globe.

The extensive overseas exploration, with the

Portuguese and

Spanish at the forefront, later joined by the

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

,

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, and

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, emerged as a powerful factor in European culture, most notably the

European encounter and colonization of the Americas. It also marks an increased adoption of

colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

as a government policy in several European states. As such, it is sometimes synonymous with the

first wave of European colonization.

European exploration outside the Mediterranean started with the maritime expeditions of Portugal to the

Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

in 1336, and later with the

Portuguese discoveries

Portuguese maritime exploration resulted in the numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of Eu ...

of the Atlantic archipelagos of

Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and

Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, the coast of

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

in 1434 and the

establishment of the sea route to India in 1498 by

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

, which is often considered a very remarkable voyage, as it initiated the Portuguese maritime and trade presence in

Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South Ca ...

and the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

.

A main event in the Age of Discovery took place when

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

sponsored the transatlantic

voyages of Christopher Columbus

Between 1492 and 1504, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus led four Spanish transatlantic maritime expeditions of discovery to the Americas. These voyages led to the widespread knowledge of the New World. This breakthrough inaugurated the ...

between 1492 and 1504, which saw the beginning of the

colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although Norse colonization of North America, the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizin ...

. Years later, the Spanish expedition of

Magellan–Elcano expedition made the first

circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the ...

of the globe between 1519 and 1522, which was regarded as a major achievement in seamanship, and had a significant impact on the European understanding of the world. These discoveries led to numerous naval expeditions across the

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

,

Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

, and

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

s, and land expeditions in the Americas,

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

,

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

that continued into the late 19th century, followed by the

exploration of the polar regions in the 20th century.

European overseas exploration led to the rise of

international trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significa ...

and the European

colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mode ...

s, with the contact between the

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

(Europe, Asia, and Africa) and the

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

(the Americas), as well as Australia, producing the

Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

, a wide transfer of plants, animals, food, human populations (including

slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

),

communicable diseases

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dis ...

, and culture between the

Eastern and

Western Hemispheres. The Age of Discovery and later

European exploration allowed the

mapping of the world, resulting in a new worldview and distant civilizations coming into contact. At the same time, new diseases were propagated, decimating populations not previously in contact with the Old World, particularly

concerning Native Americans. The era saw the widespread enslavement, exploitation and military conquest of native populations concurrent with the growing economic influence and spread of

European culture

The culture of Europe is rooted in its art, architecture, film, different types of music, economics, literature, and philosophy. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".

Definit ...

and technology.

Concept

The concept of discovery has been scrutinized, critically highlighting the history of the core term of this

periodization

In historiography, periodization is the process or study of categorizing the past into discrete, quantified, and named blocks of time for the purpose of study or analysis.Adam Rabinowitz. It's about time: historical periodization and Linked Ancie ...

.

The term "age of discovery" has been in the historical literature and still commonly used.

J. H. Parry, calling the period alternatively the Age of Reconnaissance, argues that not only was the era one of European explorations to regions heretofore unknown to them but that it also produced the expansion of geographical knowledge and empirical science. "It saw also the first major victories of empirical inquiry over authority, the beginnings of that close association of science, technology, and everyday work which is an essential characteristic of the modern western world."

Anthony Pagden

Anthony Robin Dermer Pagden (born May 27, 1945) is an author and professor of political science and history at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Biography

Anthony Pagden is the son of John Brian Dermer Pagden and Joan Mary Pagden. Mr ...

draws on the work of

Edmundo O'Gorman for the statement that "For all Europeans, the events of October 1492 constituted a 'discovery'. Something of which they had no prior knowledge had suddenly presented itself to their gaze." O'Gorman argues further that the physical and geographical encounter with new territories was less important than the Europeans’ effort to integrate this new knowledge into their worldview, what he calls "the invention of America". Pagden examines the origins of the terms "discovery" and "invention". In English, "discovery" and its forms in the romance languages derive from "''disco-operio'', meaning to uncover, to reveal, to expose to the gaze” with the implicit idea that what was revealed existed previously. Few Europeans during the period of explorations used the term "invention" for the European encounters, with the notable exception of

Martin Waldseemüller, whose

map first used

the term "America".

A central legal concept of the

Discovery Doctrine

The discovery doctrine, or doctrine of discovery, is a disputed interpretation of international law during the Age of Discovery, introduced into United States municipal law by the US Supreme Court Justice John Marshall in ''Johnson v. M'Intosh' ...

, expounded by the United States Supreme Court in 1823, draws on assertions of European powers' right to claim land during their explorations. The concept of "discovery" been used to enforce colonial claiming and the age of discovery, but has been also vocally challenged by

indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

and researchers.

[Frichner, Tonya Gonnella. (2010)]

“Preliminary Study of the Impact on Indigenous Peoples of the International Legal Construct Known as the Doctrine of Discovery.”

E/C.19/2010/13. Presented at the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Ninth Session, United Nations Economic and Social Council, New York, 27 Apr 2010. Many indigenous peoples have fundamentally challenged the concept and colonial claiming of "discovery" over their lands and people as forced and negating indigenous presence.

The period alternatively called the ''Age of Exploration'', has also been scrutinized through reflections on the understanding and use of

exploration

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

. Its understanding and use, like science more generally, has been discussed as being framed and used for colonial ventures, discrimination and

exploitation, by combining it with concepts such as the "

frontier

A frontier is the political and geographical area near or beyond a boundary. A frontier can also be referred to as a "front". The term came from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"—the region of a country that fronts ...

" (as in

frontierism) and

manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special virtues of the American people and th ...

,

up to the contemporary age of

space exploration

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration though is conducted both by uncrewed robo ...

.

Alternatively, the term and concept of contact, as in

first contact, has been used to shed a more nuanced and reciprocal light on the age of discovery and colonialism, using the alternative names of Age of Contact or Contact Period,

discussing it as an "unfinished, diverse project".

Overview

The Portuguese began systematically exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa in 1418, under the sponsorship of Infante Dom Henrique (

Prince Henry Prince Henry (or Prince Harry) may refer to:

People

*Henry the Young King (1155–1183), son of Henry II of England, who was crowned king but predeceased his father

*Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394–1460)

*Henry, Duke of Cornwall (Ja ...

). In 1488,

Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( 1450 – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lay in the o ...

reached the Indian Ocean by this route.

In 1492, the

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

of

Castile and

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

funded

Genoese mariner

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

's plan to sail west to reach the

Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

by crossing the Atlantic. Columbus encountered a continent uncharted by most Europeans (though it had begun to be explored and

was temporarily colonized by the Norse starting some 500 years earlier). Later, it was called America after

Amerigo Vespucci, a trader working for

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

. Portugal quickly claimed those lands under the terms of the

Treaty of Alcáçovas

The Treaty of Alcáçovas (also known as Treaty or Peace of Alcáçovas-Toledo) was signed on 4 September 1479 between the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon on one side and Afonso V and his son, Prince John of Portugal, on the other side ...

but Castile was able to persuade the Pope, who was himself a Castilian, to issue

four papal bulls to divide the world into two regions of exploration, where each kingdom had exclusive rights to claim newly discovered lands. These were modified by the

Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

, ratified by

Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or t ...

.

In 1498, a Portuguese expedition commanded by

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

reached India by sailing around Africa, opening up direct trade with Asia. While other exploratory fleets were sent from Portugal to northern North America, in the following years

Portuguese India Armadas

The Portuguese Indian Armadas ( pt, Armadas da Índia) were the fleets of ships funded by the Crown of Portugal, and dispatched on an annual basis from Portugal to India. The principal destination was Goa, and previously Cochin. These armada ...

also extended this Eastern oceanic route, touching sometimes South America and by this way opening a circuit from the New World to Asia (starting in 1500, under the command of

Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral ( or ; born Pedro Álvares de Gouveia; c. 1467 or 1468 – c. 1520) was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the European discoverer of Brazil. He was the first human ...

), and explored islands in the South Atlantic and Southern Indian Oceans. Soon, the Portuguese sailed further eastward, to the valuable

Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

in 1512, landing in China one year later.

Japan was reached by the Portuguese only in 1543. In 1513, Spanish

Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

and reached the "other sea" from the New World. Thus, Europe first received news of the eastern and western Pacific within a one-year span around 1512. East and west exploration overlapped in 1522, when a Castilian (Spanish) expedition, led by Portuguese navigator

Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

and, after his death in the

Maluku islands

The Maluku Islands (; Indonesian: ''Kepulauan Maluku'') or the Moluccas () are an archipelago in the east of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located ...

, by Spanish Basque navigator

Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano (Elkano in modern Basque; sometimes given as ''del Cano''; 1486/1487Some sources state that he was born in 1476. Most of this sources try to make a point about him participating on a military campaign at the Mediterranean ...

, sailing westward, completed the first circumnavigation of the world, while Spanish ''

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, ...

s'' explored the interior of the Americas, and later, some of the South Pacific islands. The main objective of this voyage was to disrupt Portuguese trade in the East.

Since 1495, the French, the English, and the

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

entered the race of exploration after learning of these exploits, defying the Iberian monopoly on maritime trade by searching for new routes, first to the western coasts of North and South America, through the first English and French expeditions (starting with the first expedition of

John Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal Nor ...

in 1497 to the north, in the service of England, followed by the French expeditions to South America and later to North America), and into the Pacific Ocean around South America, but eventually by following the Portuguese around Africa into the Indian Ocean; discovering Australia in 1606, New Zealand in 1642, and Hawaii in 1778. Meanwhile, from the 1580s to the 1640s, Russians explored and conquered almost the whole of

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

and Alaska in the 1730s.

Background

Rise of European trade

After the

fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its v ...

largely severed the connection between Europe and lands further east, Christian Europe was largely a backwater compared to the Arab world, which quickly conquered and incorporated large territories in the Middle East and North Africa. The Christian crusades to retake the

Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

from the Muslims was not a military success, but it did bring Europe into contact with the Middle East and the valuable goods manufactured or traded there. From the 12th century, the European economy was transformed by the interconnecting of river and sea trade routes, leading Europe to create trading networks.

Before the 12th century, a major obstacle to trade east of the

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

, which divided the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean, was Muslim control of great swaths of territory, including the Iberian peninsula and the trade monopolies of Christian city-states on the Italian peninsula, especially

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and

Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

. Economic growth of Iberia followed the

Christian reconquest

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

of

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

in what is now southern Spain and the

Siege of Lisbon (1147 AD), in Portugal. The decline of

Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a ...

naval strength that started before the

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

helped the maritime Italian states, mainly Venice, Genoa and Pisa, dominate trade in the eastern Mediterranean, with merchants there becoming wealthy and politically influential. Further changing the mercantile situation in the

Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to commun ...

was the waning of Christian Byzantine naval power following the death of Emperor

Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos ( el, Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, translit=Manouíl Komnenos, translit-std=ISO; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos (; " born in the purple"), was a Byzantine empero ...

in 1180, whose dynasty had made several notable treaties and concessions with Italian traders, permitting the use of Byzantine Christian ports. The

Norman Conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqu ...

in the late 11th century allowed for peaceful trade on the North Sea. The

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label= Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

, a confederation of merchant guilds and their towns in northern Germany along the North Sea and Baltic Sea, was instrumental in commercial development of the region. In the 12th century, the region of

Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

,

Hainault and

Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

produced the finest quality textiles in northern Europe, which encouraged merchants from Genoa and Venice to sail there directly from the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar and up the Atlantic coast.

Nicolòzzo Spinola made the first recorded direct voyage from

Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

to Flanders in 1277.

Technology: Ship design and the compass

Technological advancements that were important to the Age of Exploration were the adoption of the

magnetic compass and advances in ship design.

The compass was an addition to the ancient method of navigation based on sightings of the sun and stars. The compass had been used for navigation in China by the 11th century and was adopted by the Arab traders in the Indian Ocean. The compass spread to Europe by the late 12th or early 13th century.

[ A companion to the PBS Series ''The Genius That Was China''.] Use of the compass for navigation in the Indian Ocean was first mentioned in 1232.

The first mention of use of the compass in Europe was in 1180.

The Europeans used a "dry" compass, with a needle on a pivot. The compass card was also a European invention.

The

Javanese built ocean going merchant ships called ''

po'' since at least the 1st century AD. It was over 50 m in length and had a

freeboard of 5.2–7.8 m. The ''po'' was capable of carrying 700 people together with more than 10,000 ''hú'' (斛) of cargo (250–1000 tons according to various interpretations). They are built with multiple planks to resist storms, and had 4 sails plus a

bowsprit sail.

Ships grew in size, required smaller crews and were able to sail longer distances without stopping. This led to significant lower long-distance shipping costs by the 14th century.

remained popular for trade because of their low cost.

Galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be u ...

s were also used in trade.

Early geographical knowledge and maps

The ''

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' ( grc, Περίπλους τῆς Ἐρυθρᾶς Θαλάσσης, ', modern Greek '), also known by its Latin name as the , is a Greco-Roman periplus written in Koine Greek that describes navigation and ...

'', a document dating from 40 to 60 AD, describes a newly discovered route through the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

to

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, with descriptions of the markets in towns around Red Sea,

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

and the Indian Ocean, including along the eastern coast of Africa, which states "for beyond these places the unexplored ocean curves around toward the west, and running along by the regions to the south of Aethiopia and Libya and Africa, it mingles with the western sea (possible reference to the Atlantic Ocean)". European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends, dating back from the time of the conquests of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and his successors.

Another source was the

Radhanite Jewish trade networks of merchants established as go-betweens between Europe and the Muslim world during the time of the

Crusader states

The Crusader States, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic realms in the Middle East that lasted from 1098 to 1291. These feudal polities were created by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through conquest and political i ...

.

In 1154, the

Arab geographer

Medieval Islamic geography and cartography refer to the study of geography and cartography in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age (variously dated between the 8th century and 16th century). Muslim scholars made advances to the map-m ...

Muhammad al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الإدريسي القرطبي الحسني السبتي; la, Dreses; 1100 – 1165), was a Muslim geographer, cartogra ...

created a description of the world and a

world map

A world map is a map of most or all of the surface of Earth. World maps, because of their scale, must deal with the problem of projection. Maps rendered in two dimensions by necessity distort the display of the three-dimensional surface of ...

, the

Tabula Rogeriana, at the court of King

Roger II of Sicily

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became Duke of Apulia and Calabria i ...

,

[Houben, 2002, pp. 102–04.][Harley & Woodward, 1992, pp. 156–61.] but still Africa was only partially known to either Christians, Genoese and Venetians, or the Arab seamen, and its southern extent unknown. There were reports of great African

Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, but the factual knowledge was limited for the Europeans to the Mediterranean coasts and little else since the Arab blockade of North Africa precluded exploration inland. Knowledge about the Atlantic African coast was fragmented and derived mainly from

old

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

*Old, Northamptonshire, England

* Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, M ...

Greek and Roman maps based on Carthaginian knowledge, including the time of

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

exploration of

Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

. The

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

was barely known and only trade links with the

Maritime republics

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were Thalassocracy, thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in I ...

, the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

especially, fostered collection of accurate maritime knowledge.

Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the

Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

of

Ming China

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

sponsored a series of long range

tributary missions under the command of

Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferr ...

(Cheng Ho).

[ Arnold 2002, p. 7.] The fleets visited

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

,

East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

,

Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

and

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

. But the journeys, reported by

Ma Huan

Ma Huan (, Xiao'erjing: ) (c. 1380–1460), courtesy name Zongdao (), pen name Mountain-woodcutter (會稽山樵), was a Chinese voyager and translator who accompanied Admiral Zheng He on three of his seven expeditions to the Western Oceans. Ma ...

, a

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

voyager and translator, were halted abruptly after the emperor's death

[ Mancall 2006, p. 17.] and were not followed up, as the Chinese

Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

retreated in the ''

haijin'', a policy of

isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

, having limited maritime trade.

By 1400, a Latin translation of

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's ''

Geographia

The ''Geography'' ( grc-gre, Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, ''Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis'', "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, com ...

'' reached Italy coming from Constantinople. The rediscovery of Roman geographical knowledge was a revelation, both for map-making and worldview, although reinforcing the idea that the Indian Ocean was landlocked.

Medieval European travel (1241–1438)

A prelude to the Age of Discovery was a series of European expeditions crossing

Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

by land in the late Middle Ages. The

Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

had threatened Europe, but Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the ''

Pax Mongolica'' allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching from the Middle East to China.

[ DeLamar 1992, p. 328.] A series of Europeans took advantage of these to explore eastwards. Most were Italians, as trade between Europe and the Middle East was controlled mainly by the

Maritime republics

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were Thalassocracy, thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in I ...

. The close

Italian links to the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

raised great curiosity and commercial interest in countries which lay further east.

There are a few accounts of merchants from North Africa and the Mediterranean region who traded in the Indian Ocean in late medieval times.

Christian embassies were sent as far as

Karakorum

Karakorum ( Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian Script:, ''Qaraqorum''; ) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in t ...

during the

Mongol invasions of the Levant

Starting in the 1240s, the Mongols made repeated invasions of Syria or attempts thereof. Most failed, but they did have some success in 1260 and 1300, capturing Aleppo and Damascus and destroying the Ayyubid dynasty. The Mongols were forced to r ...

, from which they gained a greater understanding of the world. The first of these travellers was

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, dispatched by

Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

to the

Great Khan, who journeyed to

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

and back from 1241 to 1247.

About the same time, Russian prince

Yaroslav of Vladimir

Yaroslav II (), Christian name ''Theodor'' () (8 February 1191 – 30 September 1246) was the Grand Prince of Vladimir (1238–1246) who helped to restore his country and capital after the Mongol invasion of Rus'.

Prince of Pereyaslav

Yaroslav ...

, and subsequently his sons

Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Yaroslavich Nevsky (russian: Александр Ярославич Невский; ; 13 May 1221 – 14 November 1263) served as Prince of Novgorod (1236–40, 1241–56 and 1258–1259), Grand Prince of Kiev (1236–52) and Gran ...

and

Andrey II of Vladimir, travelled to the Mongolian capital. Though having strong political implications, their journeys left no detailed accounts. Other travellers followed, like French

André de Longjumeau and Flemish

William of Rubruck

William of Rubruck ( nl, Willem van Rubroeck, la, Gulielmus de Rubruquis; ) was a Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer.

He is best known for his travels to various parts of the Middle East and Central Asia in the 13th century, including the ...

, who reached China through Central Asia.

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295, describing being a guest at the

Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

court of

Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

in ''

Travels'', and it was read throughout Europe.

The Muslim fleet guarding the Strait of Gibraltar was defeated by Genoa in 1291. In that year, the Genoese attempted their first Atlantic exploration attempt when merchant brothers

Vadino and Ugolino Vivaldi sailed from Genoa with two galleys but disappeared off the Moroccan coast, feeding the fears of oceanic travel. From 1325 to 1354, a

Moroccan scholar from

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

,

Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim ...

, journeyed through North Africa, the Sahara desert, West Africa, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, having reached China. After returning, he dictated an account of his journeys to a scholar he met in Granada, ''

The Rihla'' ("The Journey"), the unheralded source on his adventures. Between 1357 and 1371 a book of supposed travels compiled by

John Mandeville

Sir John Mandeville is the supposed author of ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371. The earliest-surviving text is in French.

By aid of translations into many other languages, the ...

acquired extraordinary popularity. Despite the unreliable and often fantastical nature of its accounts it was used as a reference for the East, Egypt, and the Levant in general, asserting the old belief that Jerusalem was the

centre of the world.

Following the period of

Timurid relations with Europe

Timurid relations with Europe developed in the early 15th century, as the Turco-Mongol ruler Timur (Tamerlane) and European monarchs attempted to operate a rapprochement against the expansionist Ottoman Empire. Although the Timurid Mongols had be ...

, in 1439

Niccolò de' Conti published an account of his travels as a Muslim merchant to India and Southeast Asia and, later in 1466–1472, Russian merchant

Afanasy Nikitin of

Tver

Tver ( rus, Тверь, p=tvʲerʲ) is a city and the administrative centre of Tver Oblast, Russia. It is northwest of Moscow. Population:

Tver was formerly the capital of a powerful medieval state and a model provincial town in the Russi ...

travelled to India, which he described in his book ''

A Journey Beyond the Three Seas

''A Journey Beyond the Three Seas'' (russian: Хожение за три моря, ''Khozheniye za tri morya'') is a Russian literary monument in the form of travel notes, made by a merchant from Tver, Afanasiy Nikitin during his journey to Ind ...

''.

These overland journeys had little immediate effect. The

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

collapsed almost as quickly as it formed and soon the route to the east became more difficult and dangerous. The

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

of the 14th century also blocked travel and trade. The rise of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

further limited the possibilities of European overland trade.

Chinese missions (1405–1433)

The Chinese had wide connections through trade in Asia and had been sailing to

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

,

East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

, and

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

since the

Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(AD 618–907). Between 1405 and 1421, the third Ming emperor

Yongle

Yongle () (23 January 1403 – 19 January 1425) was the era name of the Yongle Emperor, the third emperor of the Ming dynasty of China.

Comparison table

Other eras contemporaneous with Yongle

* Vietnam

** ''Thiệu Thành'' (紹成, 1401– ...

sponsored a series of long range

tributary missions in the Indian Ocean under the command of admiral

Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferr ...

(Cheng Ho).

As important as they are, these voyages did not result in permanent links to overseas territories because of isolationist policy changes in China ending the voyages and knowledge of them.

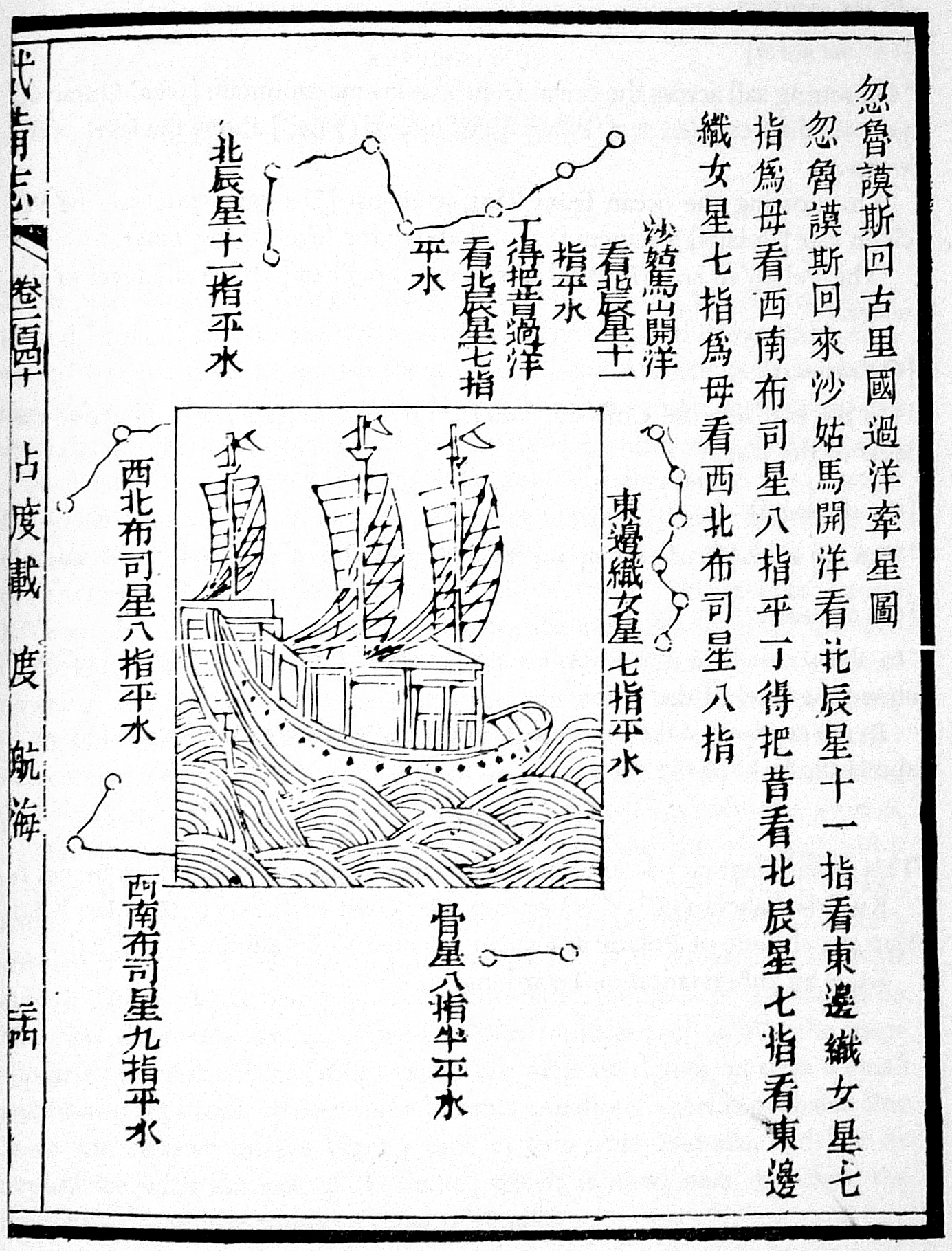

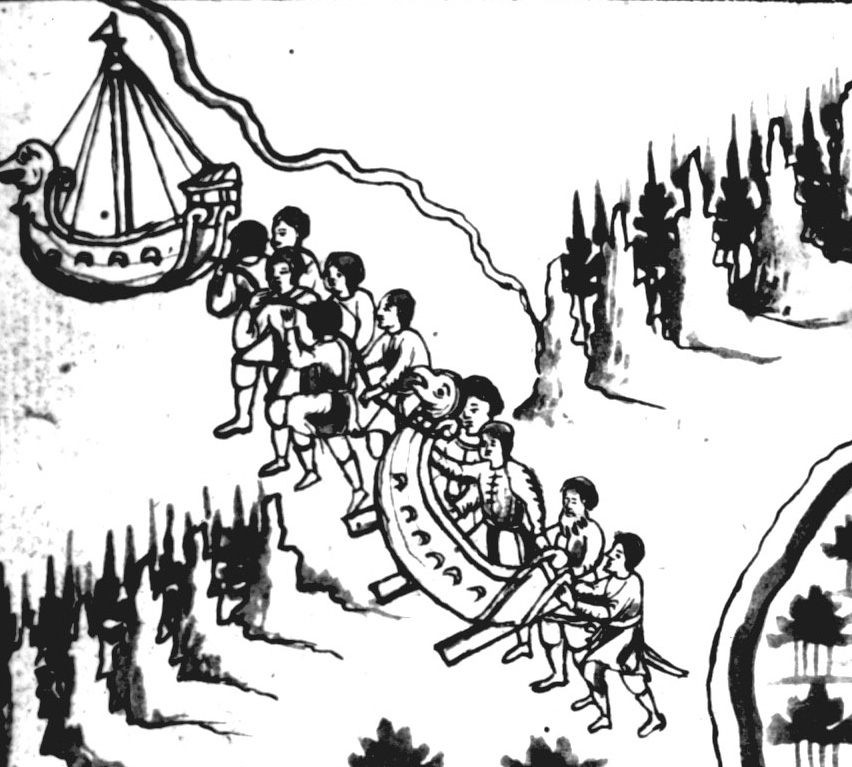

A large fleet of new

junk ships was prepared for these international diplomatic expeditions. The largest of these junks—that the Chinese termed

''bao chuan'' (treasure ships)—may have measured 121 metres (400 feet) stem to stern, and thousands of sailors were involved. The first expedition departed in 1405. At least seven well-documented expeditions were launched, each bigger and more expensive than the last. The fleets visited

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

,

East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

,

Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago ( Indonesian/ Malay: , tgl, Kapuluang Malay) is the archipelago between mainland Indochina and Australia. It has also been called the " Malay world," " Nusantara", "East Indies", Indo-Australian Archipelago, Spices Arc ...

and

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

(at the time called

Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

), exchanging goods along the way. They presented gifts of gold, silver,

porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

and

silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

; in return, received such novelties as

ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds of the genus ''Struthio'' in the order Struthioniformes, part of the infra-class Palaeognathae, a diverse group of flightless birds also known as ratites that includes the emus, rheas, and kiwis. There ...

es,

zebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: the Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. zebr ...

s,

camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

s,

ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

and

giraffe

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, '' Giraffa camelopardal ...

s. After the emperor's death, Zheng He led a final expedition departing from Nanking in 1431 and returning to Beijing in 1433. It is very likely that this last expedition reached as far as

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

. The travels were reported by

Ma Huan

Ma Huan (, Xiao'erjing: ) (c. 1380–1460), courtesy name Zongdao (), pen name Mountain-woodcutter (會稽山樵), was a Chinese voyager and translator who accompanied Admiral Zheng He on three of his seven expeditions to the Western Oceans. Ma ...

, a Muslim voyager and translator who accompanied Zheng He on three of the seven expeditions, his account published as the ''

Yingya Shenglan

The ''Yingya Shenglan'' (), written by Ma Huan in 1451, is a book about the countries visited by him over the course of the Ming treasure voyages led by Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diploma ...

'' (Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores) (1433).

The voyages had a significant and lasting effect on the organization of a

maritime network, utilizing and creating nodes and conduits in its wake, thereby restructuring international and cross-cultural relationships and exchanges.

[ It was especially impactful as no other polity had exerted naval dominance over all sectors of the Indian Ocean prior to these voyages. The Ming promoted alternative nodes as a strategy to establish control over the network.][.] For instance, due to Chinese involvement, ports such as Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has bee ...

(in Southeast Asia), Cochin

Kochi (), also known as Cochin ( ) ( the official name until 1996) is a major port city on the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea, which is a part of the Arabian Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of ...

(on the Malabar Coast), and Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban cent ...

(on the Swahili Coast) had grown as key alternatives to other important and established ports. The appearance of the Ming treasure fleet generated and intensified competition among contending polities and rivals, each seeking an alliance with the Ming.[

The voyages also brought about the Western Ocean's regional integration and the increase in international circulation of people, ideas, and goods. It also provided a platform for ]cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

discourses, which took place in locations such as the ships of the Ming treasure fleet, the Ming capitals of Nanjing as well as Beijing, and the banquet receptions organized by the Ming court for foreign representatives.[.] Diverse groups of people from across the maritime countries congregated, interacted, and traveled together as the Ming treasure fleet sailed from and to Ming China.[ For the first time in its history, the maritime region from China to Africa was under the dominance of a single imperial power and thereby allowed for the creation of a cosmopolitan space.

These long-distance journeys were not followed up, as the Chinese Ming dynasty retreated in the '' haijin'', a policy of ]isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

, having limited maritime trade. Travels were halted abruptly after the emperor's death, as the Chinese lost interest in what they termed barbarian lands, turning inward,Hongxi Emperor

The Hongxi Emperor (16 August 1378 – 29 May 1425), personal name Zhu Gaochi (朱高熾), was the fourth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1424 to 1425. He succeeded his father, the Yongle Emperor, in 1424. His era name "Hongxi" means ...

ended further expeditions and Xuande Emperor suppressed much of the information about Zheng He's voyages.

Atlantic Ocean (1419–1507)

From the 8th century until the 15th century, the

From the 8th century until the 15th century, the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

and neighboring maritime republics

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were Thalassocracy, thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in I ...

held the monopoly of European trade with the Middle East. The silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

and spice trade, involving spices, incense

Incense is aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremony. It may also b ...

, herbs, drugs and opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

, made these Mediterranean city-states phenomenally rich. Spices were among the most expensive and demanded products of the Middle Ages, as they were used in medieval medicine, religious rituals, cosmetics, perfumery, as well as food additives and preservatives. They were all imported from Asia and Africa.

Muslim traders—mainly descendants of Arab sailors from Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

and Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

—dominated maritime routes throughout the Indian Ocean, tapping source regions in the Far East and shipping for trading emporiums in India, mainly Kozhikode

Kozhikode (), also known in English as Calicut, is a city along the Malabar Coast in the state of Kerala in India. It has a corporation limit population of 609,224 and a metropolitan population of more than 2 million, making it the second ...

, westward to Ormus

The Kingdom of Ormus (also known as Hormoz; fa, هرمز; pt, Ormuz) was located in the eastern side of the Persian Gulf and extended as far as Bahrain in the west at its zenith. The Kingdom was established in 11th century initially as a dep ...

in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

and Jeddah

Jeddah ( ), also spelled Jedda, Jiddah or Jidda ( ; ar, , Jidda, ), is a city in the Hejaz region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and the country's commercial center. Established in the 6th century BC as a fishing village, Jeddah's pro ...

in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

. From there, overland routes led to the Mediterranean coasts. Venetian merchants distributed the goods through Europe until the rise of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, that eventually led to the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

in 1453, barring Europeans from important combined-land-sea routes in areas around the Aegean, Bosporus, and Black Sea.bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes fro ...

leading to the development of a complex banking system to manage the risks in trade (the very first state bank, '' Banco di San Giorgio'', was founded in 1407 at Genoa). Sailing also into the ports of Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

(Flanders) and England, Genoese communities were then established in Portugal, who profited from their enterprise and financial expertise.

European sailing had been primarily close to land cabotage, guided by portolan chart

Portolan charts are nautical charts, first made in the 13th century in the Mediterranean basin and later expanded to include other regions. The word ''portolan'' comes from the Italian ''portulano'', meaning "related to ports or harbors", and wh ...

s. These charts specified proven ocean routes guided by coastal landmarks: sailors departed from a known point, followed a compass heading, and tried to identify their location by its landmarks. For the first oceanic exploration Western Europeans used the compass, as well as progressive new advances in cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

and astronomy. Arab navigational tools like the astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

and quadrant were used for celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface o ...

.

Portuguese exploration

In 1297, King Dinis of Portugal took personal interest in exports. In 1317, he made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Pessagno), appointing him first

In 1297, King Dinis of Portugal took personal interest in exports. In 1317, he made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Pessagno), appointing him first admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

of the Portuguese Navy

The Portuguese Navy ( pt, Marinha Portuguesa, also known as ''Marinha de Guerra Portuguesa'' or as ''Armada Portuguesa'') is the naval branch of the Portuguese Armed Forces which, in cooperation and integrated with the other branches of the Port ...

, with the goal of defending the country against Muslim pirate raids. Outbreaks of bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

led to severe depopulation in the second half of the 14th century: only the sea offered alternatives, with most population settling in fishing and trading coastal areas. Between 1325 and 1357, Afonso IV of Portugal

Afonso IVEnglish: ''Alphonzo'' or ''Alphonse'', or ''Affonso'' (Archaic Portuguese), ''Alfonso'' or ''Alphonso'' (Portuguese-Galician) or ''Alphonsus'' (Latin). (; 8 February 129128 May 1357), called the Brave ( pt, o Bravo, links=no), was King ...

encouraged maritime commerce and ordered the first explorations. The Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

, already known to the Genoese, were claimed as officially discovered under patronage of the Portuguese but in 1344 Castile disputed them, expanding their rivalry into the sea.

To ensure their monopoly on trade, Europeans (beginning with the Portuguese) attempted to install a mediterranean system of trade which used military might and intimidation to divert trade through ports they controlled; there it could be taxed. In 1415, Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territori ...

was conquered by the Portuguese aiming to control navigation of the African coast. Young prince Henry the Navigator

''Dom'' Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu (4 March 1394 – 13 November 1460), better known as Prince Henry the Navigator ( pt, Infante Dom Henrique, o Navegador), was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15t ...

was there and became aware of profit possibilities in the Trans-Saharan trade

Trans-Saharan trade requires travel across the Sahara between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa. While existing from prehistoric times, the peak of trade extended from the 8th century until the early 17th century.

The Sahara once had a very d ...

routes. For centuries slave and gold trade routes linking West Africa with the Mediterranean passed over the Western Sahara Desert, controlled by the Moors of North Africa.

Henry wished to know how far Muslim territories in Africa extended, hoping to bypass them and trade directly with West Africa by sea, find allies in legendary Christian lands to the south like the long-lost Christian kingdom of Prester John

Prester John ( la, Presbyter Ioannes) was a legendary Christian patriarch, presbyter, and king. Stories popular in Europe in the 12th to the 17th centuries told of a Nestorian patriarch and king who was said to rule over a Christian nation lost ...

and to probe whether it was possible to reach the Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

by sea, the source of the lucrative spice trade. He invested in sponsoring voyages down the coast of Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

, gathering a group of merchants, shipowners and stakeholders interested in new sea lanes. Soon the Atlantic islands of Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

(1419) and the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

(1427) were reached. In particular, they were discovered by voyages launched by the command of Prince Henry the Navigator

''Dom'' Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu (4 March 1394 – 13 November 1460), better known as Prince Henry the Navigator ( pt, Infante Dom Henrique, o Navegador), was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15t ...

. The expedition leader himself, who established settlements on the island of Madeira, was Portuguese explorer João Gonçalves Zarco.

At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Non (Cape Chaunar) on the African coast, and whether it was possible to return once it was crossed. Nautical myths warned of oceanic monsters or an edge of the world, but Prince Henry's navigation challenged such beliefs: starting in 1421, systematic sailing overcame it, reaching the difficult Cape Bojador