African Americans in Omaha, Nebraska on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

African Americans in Omaha, Nebraska are central to the development and growth of the 43rd largest city in the United States. The first free black settler in the city arrived in 1854, the year the city was incorporated.Pipher, M. (2002

"Chapter One

," ''The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community.'' Harcourt. In 1894 black residents of Omaha organized the first fair in the United States for African-American exhibitors and attendees.Nebraska Writers Project (n.d. ''est 1938''

Negros in Nebraska

''Workers Progress Administration.'' Retrieved October 29, 2007. The 2000 US Census recorded 51,910 African Americans as living in Omaha (over 13% of the city's population). In the 19th century, the growing city of Omaha attracted ambitious people making new lives, such as Dr.

"Big plans in store for north Omaha"

''Omaha World-Herald'', October 3, 2007. Retrieved 10/4/07. The city ranks number one in the United States by the number of black children that live in poverty, with nearly six of 10 black kids living below the poverty line. Only one other metropolitan area in the U.S.,

"Omaha in Black and White: Poverty amid prosperity"

''Omaha World-Herald''. April 15, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

Multiethnic Guide.

'' Greater Omaha Economic Partnership. Retrieved October 28, 2007. The presence of several

Before Omaha's African-American residents gathered in

Before Omaha's African-American residents gathered in

''Project Prospect: A youth investigation of blacks buried at Prospect Cemetery

' Girls Club of Omaha. Retrieved October 28, 2007. In the 1880s, Omaha's original "Negro district" was located at Twentieth and Harney Streets.(1936) ''Henry Black: Life Histories from the Folklore Project, WPA Federal Writers' Project, 1936–1940; American Memory''

. The Near North Side, located immediately north of

Information on the video here.

/ref> During the 1930s, the Federal government built

"Chapter One

," ''The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community.'' Harcourt. In 1894 black residents of Omaha organized the first fair in the United States for African-American exhibitors and attendees.Nebraska Writers Project (n.d. ''est 1938''

Negros in Nebraska

''Workers Progress Administration.'' Retrieved October 29, 2007. The 2000 US Census recorded 51,910 African Americans as living in Omaha (over 13% of the city's population). In the 19th century, the growing city of Omaha attracted ambitious people making new lives, such as Dr.

Matthew Ricketts

Matthew Oliver Ricketts (April 3, 1858 – January 3, 1917) was an American politician and physician. He was the first African-American member of the Nebraska Legislature, where he served two terms in the Nebraska House of Representatives (th ...

and Silas Robbins. Dr. Ricketts was the first African American to graduate from a Nebraska college or university. Silas Robbins was the first African American to be admitted to the bar in Nebraska. In 1892 Dr. Ricketts was also the first African American to be elected to the Nebraska State Legislature. Ernie Chambers, an African-American barber from North Omaha's 11th District, became the longest serving state senator in Nebraska history in 2005 after serving in the unicameral for more than 35 years.

Because of its industrial jobs with the railroads and meatpacking industries, Omaha was the city on the Plains that attracted the most African-American migrants from the South in the Great Migration of the early 20th century. By 1910 it had the third largest black population among western cities after Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

and Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

and from 1910 to 1920, the African-American population in Omaha doubled to more than 10,000, as new migrants were attracted by jobs in the expanding meatpacking industry. More than 70 percent were from the South. Of western cities, in 1920 only Los Angeles had a greater population of blacks than Omaha, with nearly 16,000. Reflecting the concentration of people and vital community, in 1915 the Lincoln Motion Picture Company

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company was an American film production company founded in 1916 by Noble Johnson and George Perry Johnson. Noble Johnson was president of the company, and the secretary was actor Clarence A. Brooks. Dr. James T. Smit ...

was founded in Omaha. It was the first film company owned by African Americans. Like several other major industrial cities during the "Red Summer of 1919

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civi ...

", Omaha suffered a race riot. It was marked by the lynching of Will Brown, a black worker, and deaths of two white men. The violence erupted out of job competition and postwar social tensions among working class groups, aggravated by sensational journalism in the city. In the aftermath of the riot, the city's residential patterns became more segregated. By the 1920s, a vibrant African-American musical and entertainment culture had developed in the city.

While African Americans were already concentrated in North Omaha, in the 1930s redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services ( financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have sign ...

and race restrictive covenants reinforced their staying there without options for years to move to newer housing. In the 1930s and 1940s African Americans were part of successful interracial organizing teams in the meatpacking industry. They succeeded in creating the integrated United Meatpacking Workers of America union and gained an end to segregated jobs in the industry. The union helped support integration of public facilities in the 1950s and the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

in the 1960s. During this period, activists worked both for local and national changes; they contributed to improving conditions for African Americans in Omaha. Mid-century massive restructuring in railroads and the meatpacking industry cost the city more than 10,000 jobs. African Americans were particularly affected by the loss of industrial jobs. Those who could migrated for work in other areas and problems increased among the remaining population in North Omaha.

Omaha has the fifth-highest African-American poverty rate among the nation's 100 largest cities, with more than one in three black residents in Omaha living below the poverty line.Kotock, C. D. (2007)"Big plans in store for north Omaha"

''Omaha World-Herald'', October 3, 2007. Retrieved 10/4/07. The city ranks number one in the United States by the number of black children that live in poverty, with nearly six of 10 black kids living below the poverty line. Only one other metropolitan area in the U.S.,

Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

, has a wider economic disparity between blacks and whites.Cordes, H.J., Gonzalez, C. and Grace, E"Omaha in Black and White: Poverty amid prosperity"

''Omaha World-Herald''. April 15, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

Population history

The first recorded instance of ablack person

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in s ...

in the Omaha area occurred in 1804. "York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

" was a slave belonging to William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Miss ...

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

.Multiethnic Guide.

'' Greater Omaha Economic Partnership. Retrieved October 28, 2007. The presence of several

black people

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in ...

, probably slaves, was recorded in the area comprising North Omaha today when Major Stephen H. Long

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most pro ...

's expedition arrived at Fort Lisa in September 1819. They reportedly lived at the post and in neighboring farmsteads.

19th century

After a short history of slavery in Nebraska, the first free black person to live in Omaha was Sally Bayne, who moved to Omaha in 1854. A clause in the original proposed Nebraska State Constitution from 1854 limitedvoting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

in the state to "free white males", which kept Nebraska from entering the Union for almost a year. In the 1860s, the U.S. Census showed 81 "Negroes" in Nebraska, ten of whom were accounted for as slaves. At that time, the majority of the population lived in Omaha and Nebraska City

Nebraska City is a city in Nebraska, and the county seat of, Otoe County, Nebraska, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 7,289.

The Nebraska State Legislature has credited Nebraska City as being the oldest incorporated ...

.

Some of the earliest African-American residents of the city may have arrived by the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

via a small log cabin outside of Nebraska City

Nebraska City is a city in Nebraska, and the county seat of, Otoe County, Nebraska, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 7,289.

The Nebraska State Legislature has credited Nebraska City as being the oldest incorporated ...

built by Allen Mayhew in 1855. It is honored today as the Mayhew Cabin

The Mayhew Cabin (officially Mayhew Cabin & Historic Village, also known as John Brown's Cave), in Nebraska City, Nebraska, is the only Underground Railroad site in Nebraska officially recognized by the National Park Service. It is included among ...

Museum. One report says, "Henry Daniel Smith, born in Maryland in 1835, still living in Omaha in 1913 and working at his trade of broom-maker, was one escaped slave who entered Nebraska via the Underground Railroad."

By 1867 enough blacks gathered in community to found St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church in the Near North Side neighborhood. It was the first church for African Americans in Nebraska. The first recorded birth of an African American in Omaha occurred in 1872, when William Leper was born.

Before Omaha's African-American residents gathered in

Before Omaha's African-American residents gathered in North Omaha

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the ...

, they lived dispersed throughout the city. By 1880 there were nearly 800 black residents, many recruited by Union Pacific Railroad as strikebreakers. By 1884 there three black churches had been founded. By 1900 there were 3,443 black residents, in a total city population of 102,555.

Black men and women quickly formed social and community organizations, such as the Women's Club in 1895, devoted to education, respectability and reform. In addition, the community began to create its own newspapers, such as the ''Progress'', the ''Afro-American Sentinel'' and ''The Enterprise'' in the 1880s and 1890s.

Blacks also quickly distinguished themselves in public life: in 1892 Dr. Matthew Ricketts

Matthew Oliver Ricketts (April 3, 1858 – January 3, 1917) was an American politician and physician. He was the first African-American member of the Nebraska Legislature, where he served two terms in the Nebraska House of Representatives (th ...

was the first black person elected to serve in the Nebraska Legislature

The Nebraska Legislature (also called the Unicameral) is the legislature of the U.S. state of Nebraska. The Legislature meets at the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. With 49 members, known as "senators", the Nebraska Legislature is the sm ...

and in 1895 Silas Robbins was the first black lawyer admitted to the Nebraska State Bar Association

A bar association is a professional association of lawyers as generally organized in countries following the Anglo-American types of jurisprudence. The word bar is derived from the old English/European custom of using a physical railing to se ...

.

20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, two African-American physicians, doctors Riddle and Madison, opened a hospital for African Americans. Citizens could not afford the facility and it failed financially. Reared in Omaha, Clarence W. Wigington was the first black architect to design a home in Nebraska as a student of Thomas Rogers Kimball. He also designed churches in Omaha. Wigington gained a national reputation after moving toSaint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center ...

, in 1914, where he soon became the senior architectural designer for the city. His legacy includes 60 surviving buildings, among which four are listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

.

John Grant Pegg was the Leading Colored Republican of the Western States Meet in Conference. In 1906, he was appointed as the City Weights and Measures Inspector by J. C. Dalhman, Mayor of Omaha 1910. Pegg held the post for 10 years until his death in 1916. He encouraged and sponsored many of the black settlers who went by wagon out to Cherry County, Nebraska, to homestead benefiting from The Kincaid Homestead Act of 1904, where a black colony was established and where his brother, Charles T. Pegg, lived.

In 1912, the Omaha chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.& ...

, the first NAACP chapter west of the Mississippi. George Wells Parker

George Wells Parker (September 18, 1882 – July 28, 1931) was an African-American political activist, historian, public intellectual, and writer who co-founded the Hamitic League of the World.

Biography

George Wells Parker's parents were b ...

, a founder of the Afrocentric Hamitic League of the World, was instrumental in recruiting African Americans from the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

to Omaha during the 1910s.

Railroads and the meatpacking industry recruited African American workers from the South. From 1910 to 1920, the African-American population of Omaha doubled from 4,426 to 10,315, making up five percent of Omaha's population. Of the western cities which were new destinations for blacks of the Great Migration, in 1920 Omaha had the second-largest black population, after Los Angeles. The rapid pace of growth alarmed some people in the city, which was also absorbing thousands of new eastern and southern European immigrants. People were concerned about social problems: labor unrest following strikes in 1917, and the return of veterans looking for work after World War I.

During the first week of August 1919, the ''Omaha Bee

The ''Omaha Daily Bee'' was a leading Republican newspaper that was active in the late 19th and early 20th century. The paper's editorial slant frequently pitted it against the ''Omaha Herald'', the '' Omaha Republican'' and other local papers. ...

'' newspaper reported that as many as 500 "Negro" workers, mostly from Chicago and East St. Louis, arrived in Omaha to seek employment in the packinghouses. The ''Bee'' tended to sensational journalism, adding to tensions in the city as it highlighted alleged crimes committed by blacks. The migration of African Americans to Omaha and the hiring of black workers created a source of friction in the local labor market. Blacks had been hired as strikebreakers

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the str ...

in 1917, and there was a major strike among white workers in 1919. The immigrant workers in the meatpacking industry resented the strikebreakers. Economic pressure exacerbated hostilities.

From 1910 to the 1950s, Omaha was a destination for African Americans during the Great Migration from the American South. An African-American cultural expansion flourished beginning in the 1920s, part of a larger boom time in the Prohibition era. A late 20th-century documentary reported about the 1940s, "On the surface the black community appeared quite stable. Its center was a several-block district north of the downtown. There were over a hundred black-owned businesses, and there were a number of black physicians, dentists, and attorneys. Over twenty fraternal organizations and clubs flourished. Church life was diverse. Of more than forty denominations, Methodists and Baptists predominated."

Neighborhoods

Early African American neighborhoods in Omaha included Casey's Row, a community of housing for African-American families, most of whose men worked as railroad porters at the nearby Union Pacific Railroad. The steady jobs on the railroads were considered good work, even if some men had greater ambitions.(1981)''Project Prospect: A youth investigation of blacks buried at Prospect Cemetery

' Girls Club of Omaha. Retrieved October 28, 2007. In the 1880s, Omaha's original "Negro district" was located at Twentieth and Harney Streets.(1936) ''Henry Black: Life Histories from the Folklore Project, WPA Federal Writers' Project, 1936–1940; American Memory''

. The Near North Side, located immediately north of

Downtown Omaha

Downtown Omaha is the central business, government and social core of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area, U.S. state of Nebraska. The boundaries are Omaha's 20th Street on the west to the Missouri River on the east and the centerline ...

, is where the majority of African Americans have lived in Omaha for almost 100 years. Originally the community had mostly European immigrants: Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, Italians and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and gradually drew more African Americans. In pre-1900 Omaha, the city's cemetery was always integrated.

The community became more racially segregated soon after the Omaha Race Riot of 1919

The Omaha Race Riot occurred in Omaha, Nebraska, September 28–29, 1919. The race riot resulted in the lynching of Will Brown, a black civilian; the death of two white rioters; the injuries of many Omaha Police Department officers and civili ...

. During that event an African-American worker named Will Brown was lynched by a white mob outside the Douglas County Courthouse. After the mob finished with Brown, they turned against the entire population of African Americans in the Near North Side; however, their efforts were thwarted by soldiers from Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

. In the following years the city began enforcing race-restrictive covenants. Properties for rent and sale were restricted on the basis of race, with the primary intent of keeping the Near North Side "black" and the rest of the city "white". These agreements were held in place with redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services ( financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have sign ...

, a system of segregated insuring and lending reinforced by the federal government. These restrictions were ruled illegal in 1940.(1992) ''A Street of Dreams'' Nebraska Public TelevisionInformation on the video here.

/ref> During the 1930s, the Federal government built

housing project

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, d ...

s for working families: the Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project was a historic public housing site located from 20th to 24th Streets, and from Paul to Seward Streets in the historic Near North Side neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was built in 1938 by the P ...

in North Omaha and a similar project in South Omaha. Both were intended to improve housing for the large working-class community, whose majority then were immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe and their descendants. With job losses and demographic changes accelerating in the late 1950s and 1960s, the project residents in North Omaha became nearly all poor and low-income

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little African Americans. By the early first decade of the 21st century, each of these facilities was torn down and replaced with public housing schemes featuring mixed-income and supporting uses.

''The African American Registry''. Retrieved 8/4/07. George and Noble Johnson founded the

No African Americans served on the Omaha City Council or

No African Americans served on the Omaha City Council or

During this period, North Omaha and its main artery of

During this period, North Omaha and its main artery of

Starting in 1920, the Colored Commercial Club organized to help blacks in Omaha secure employment and to encourage business enterprises among African Americans. The National Federation of Colored Women had five chapters in Omaha. In 1927 the first

Starting in 1920, the Colored Commercial Club organized to help blacks in Omaha secure employment and to encourage business enterprises among African Americans. The National Federation of Colored Women had five chapters in Omaha. In 1927 the first

''Omaha Reader''. Retrieved July 26, 2007. North Omaha was marred by race-related violence and de facto segregation throughout the 20th century. When the

The End of Desegregation?

' Nova Science Publishers, p. 12. The inability of government money to solve the problems of Omaha's African American community was accented by white flight. The city's schools were greatly affected by racial unrest. Consequential to the 1971 ''

"Deeper pockets"

''

African American Information

NEGenWeb Project * (2003)

' CFC Productions. * (1940)

The Negroes of Nebraska

'. Nebraska Writers' Project. Works Progress Administration.

African American Empowerment Network

Building Bright Futures

African-American neighborhood

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African American ...

s in Omaha have been studied extensively; the most notable reports include Lois Mark Stalvey's ''Three to Get Ready: The Education of a White Family in Inner City Schools'', and the 1966 documentary film ''A Time for Burning

''A Time for Burning'' is a 1966 American documentary film that explores the attempts of the minister of Augustana Lutheran Church in Omaha, Nebraska, to persuade his all-white congregation to reach out to " Negro" Lutherans in the city's nort ...

''. This movie featured the opinions of the young Ernie Chambers. A barber, Chambers went on to law school and has been repeatedly elected to represent North Omaha in the Nebraska State Legislature

The Nebraska Legislature (also called the Unicameral) is the legislature of the U.S. state of Nebraska. The Legislature meets at the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. With 49 members, known as "senators", the Nebraska Legislature is the sm ...

for more than 35 years.

Occupations

TheUnion Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

first introduced large numbers of African American strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the st ...

s to Omaha during a strike in 1877. Black barbers organized the first labor union in Omaha, and went on strike in Omaha in 1887 after they deemed it "unprofessional to work beside white competitors." Arriving in 1890, Dr. Stephenson was the first African-American physician in Omaha and the start of a substantial professional class. Matthew Ricketts

Matthew Oliver Ricketts (April 3, 1858 – January 3, 1917) was an American politician and physician. He was the first African-American member of the Nebraska Legislature, where he served two terms in the Nebraska House of Representatives (th ...

was the first African-American medical student to graduate from the University of Nebraska Medical College and settled in North Omaha to set up his practice. In 1892, Dr. Ricketts was the first African American elected to a seat in the Nebraska State Legislature

The Nebraska Legislature (also called the Unicameral) is the legislature of the U.S. state of Nebraska. The Legislature meets at the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. With 49 members, known as "senators", the Nebraska Legislature is the sm ...

. According to the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

, the first African-American fair held in the United States took place in Omaha, July 3–4, 1894. Their study reports: "Only Negro-owned horses were entered in the races, and all exhibits were restricted to articles made or owned by Negroes."

African Americans also built a "Colored Old Folks Home" in North Omaha in the 1910s and sustained it for a long period of time. Clarence W. Wigington was a renowned African-American architect from Omaha. He designed St. John's A.M.E. and the Broomfield Rowhouse, among many others in the city, but built most of his career after 1914 in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Miss Lucy Gamble, later known as Mrs. John Albert Williams, was the first African-American teacher in the Omaha Public Schools, teaching there for six years from 1899 through 1905. The first film company controlled by Black filmmakers was founded in Omaha in the summer of 1915."The Lincoln Motion Picture company, a first for Black cinema!"''The African American Registry''. Retrieved 8/4/07. George and Noble Johnson founded the

Lincoln Motion Picture Company

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company was an American film production company founded in 1916 by Noble Johnson and George Perry Johnson. Noble Johnson was president of the company, and the secretary was actor Clarence A. Brooks. Dr. James T. Smit ...

to produce films for African-American audiences. Noble was a small-time actor; George worked for the post office. Noble Johnson was president of the company; Clarence A. Brooks, secretary; Dr. James T. Smith, treasurer; and Dudley A. Brooks was assistant secretary. Lincoln Films quickly built a reputation for making films that showcased African-American talent in the full sphere of cinema. In less than a year the company relocated to Los Angeles, where the major film industry was located."Urban League Formed." ''Evening World-Herald'' 29 Nov. 1927: 2. Print.

Today African Americans own fifty percent of all minority-owned businesses in Omaha.

Politics

From a slow start in the late 19th century, in the mid-20th century on, African Americans began to win more seats and appointments in politics, with their participation steadily growing. More people obtained higher education and entered professional middle classes. In 1892, Dr.Matthew Ricketts

Matthew Oliver Ricketts (April 3, 1858 – January 3, 1917) was an American politician and physician. He was the first African-American member of the Nebraska Legislature, where he served two terms in the Nebraska House of Representatives (th ...

became the first African American elected to the Nebraska State Legislature

The Nebraska Legislature (also called the Unicameral) is the legislature of the U.S. state of Nebraska. The Legislature meets at the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. With 49 members, known as "senators", the Nebraska Legislature is the sm ...

, and was the acknowledged leader of the African-American community in Omaha. After he left Omaha in 1903, Jack Broomfield, proprietor of a notorious bar in downtown Omaha

Downtown Omaha is the central business, government and social core of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area, U.S. state of Nebraska. The boundaries are Omaha's 20th Street on the west to the Missouri River on the east and the centerline ...

, became the leader of the community. He is criticized for having allowed the community to fall apart under the influence of Tom Dennison.

No African Americans served on the Omaha City Council or

No African Americans served on the Omaha City Council or Douglas County Board of Commissioners

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

* Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil ...

until district elections became law. In 1893 Edwin R. Overall, a mail carrier, ran as a Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

for the City Council. He finished 18th in a field of 23 candidates running at-large for nine of 18 council seats. In 1973 and 1977, Fred Conley ran for the Omaha City Council in the at-large format and each time finished 18th – just as Overall did some 70 years earlier. At-large elections were won by candidates who represented the majority population of the city, which was white.

In 1981, after City Council elections were changed to be based on district representation, Conley became the first African American elected. He served until 1989. In 1992, Carol Woods Harris became the first African American elected to the Douglas County Board and served until 2004.

African Americans have been represented on the Omaha School Board since 1950 when attorney Elizabeth Davis Pittman was elected. De facto school segregation, however, persisted in Omaha long after that date with school boundaries tailored to match residential areas, which had ''de facto'' segregation.

Brenda Warren Council, a former member of the Omaha School Board and the City Council, narrowly lost the 1997 mayoral election, losing by 700 votes to Mayor Hal Daub. In 2003 Thomas Warren, Brenda Council's brother, was appointed by Mayor Mike Fahey as the city's first African-American Chief of Police for the Omaha Police Department

The Omaha Police Department (OPD) is the principal law enforcement agency of the city of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It is nationally accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies. The OPD is the largest law enfo ...

.

In 2005, Marlon Polk was appointed by Governor Dave Heineman

David Eugene Heineman (born May 12, 1948) is an American politician who served as the 39th governor of Nebraska from 2005 to 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the 39th treasurer of Nebraska from 1995 to 2001 and 37th li ...

to serve as a District Court Judge, the first African American to do so in Nebraska. He was assigned to serve in Douglas County.Dreamland Historical Project (2005), ''From whence we came: A historical view of African Americans in Omaha.'' Retrieved from the Project, August 10, 2006. In 1970 Ernie Chambers became the city's second African American elected to the state legislature. Chambers has won every election since then, and in 2007 became the longest-serving Nebraska Senator in history. In 2005 the Nebraska State Legislature approved a term limit

A term limit is a legal restriction that limits the number of terms an officeholder may serve in a particular elected office. When term limits are found in presidential and semi-presidential systems they act as a method of curbing the potenti ...

law limiting legislators to two terms, forcing Chambers from office in 2008.

African-American firefighters

Hose Company #12, and later Hose Company #11, hired the first African-Americanfirefighters

A firefighter is a first responder and rescuer extensively trained in firefighting, primarily to extinguish hazardous fires that threaten life, property, and the environment as well as to rescue people and in some cases or jurisdictions also ...

in the city. One of these stations was located at 20th and Lake Streets. One of the first African-American firefighters in Omaha was James C. Greer, Sr. who was a member of the Omaha Fire Department from May 5, 1906, to August 1, 1933, and was a captain in the department for many years. Horse-drawn wagons were in use when he was assigned to the old No. 11 Station at Thirtieth and Spaulding Streets. He later served at the No. 4 Station at Sixteenth and Izard Streets. He retired as senior captain from the Omaha Fire Department in 1933. His son Richard N. Greer served as a volunteer for the fire department in the 1950s.

The first step towards integration in Omaha's Fire Department came in 1940, when an African-American firefighter was assigned to the city's Bureau of Fire Prevention and Inspection. By the 1950s, the city had two companies of African-American firefighters. Omaha's Fire Department was integrated in 1957.

African-American culture

Religious institutions

The earliest African-American churches in Omaha were St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church, organized in 1867; St. Phillip the Deacon Episcopal Church, organized in 1878, Mt. Moriah Baptist Church, organized in 1887 and Zion Baptist Church, organized in 1888. The second St. John's building and Zion's current building were designed by future master architect Clarence Wigington. St. John's current building is a notable example of thePrairie School

Prairie School is a late 19th- and early 20th-century architectural style, most common in the Midwestern United States. The style is usually marked by horizontal lines, flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves, windows grouped ...

architectural style.

In 1921, the Omaha and Council Bluffs Colored Ministerial Alliance demanded that Tom Dennison's cabarets in the Sporting District "wherein there is unwarranted mingling of the races" be closed indefinitely. It is unknown what their objectives were.

Other influential churches included Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church

Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church, located at 3105 North 24th Street, was formed in 1954 as an integrated congregation in North Omaha, Nebraska. Originally called the North Presbyterian Church, the City of Omaha has reported, "Calvin Memorial ...

, which opened in 1954 as an integrated congregation. Omaha had several interesting examples of integration in its churches, including those featured the documentary film ''A Time for Burning

''A Time for Burning'' is a 1966 American documentary film that explores the attempts of the minister of Augustana Lutheran Church in Omaha, Nebraska, to persuade his all-white congregation to reach out to " Negro" Lutherans in the city's nort ...

'' and Pearl Memorial United Methodist Church

Pearl Memorial United Methodist Church was a member of the Nebraska Conference of the United Methodist Church that was operated from the 1890s into the 2000s. The former congregation's church is located at 2319 Ogden Street in the Miller Park neig ...

, which began integration efforts in the 1970s. Sacred Heart Catholic Church has operated since the late 19th century and has evolved numerous times as different ethnic groups succeeded each other in the neighborhood. North Omaha's Lizzie Robinson founded the first Church of God in Christ

The Church of God in Christ (COGIC) is a Holiness– Pentecostal Christian denomination, and the largest Pentecostal denomination in the United States. Although an international and multi-ethnic religious organization, it has a predominantly ...

congregation in Nebraska in the 1920s. Salem Baptist Church

Salem Baptist Church is located at 3131 Lake Street in North Omaha, Nebraska, United States. Founded in 1922, it has played important roles in the history of African Americans in Omaha, and in the city's religious community. Church leadership ...

has been particularly important in the city's African-American community, hosting Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

in a major speaking event in Omaha in 1957.

Mt Moriah Baptist Church now houses the Moriah Heritage Center which contains a digital history of the African American Church in North Omaha.

Historical social clubs

The African-American community in North Omaha was anchored with numerous important social clubs. According to one report from the 1930s, "There are today in Omaha alone some twenty-five clubs and societies with a total membership of over two thousand." These groups included the Pleasant Hour Club (which was estimated to be 50 years old in the late 1930s), Aloha Club, Entre Nous Club, the Beau Brummels Club, the Dames Club, the Jolly Twenty Club, the Trojan Club, and the Quack Club. Important locations included the North Side YWCA. This influential organization, starting in 1920, was located in a house at 2306 N. 22nd Street The African-American community in Omaha also supported the Old Colored Folks' Home, which was organized in 1913. In 1923 they received funds from the city's "Community Chest" fund, with which they purchased a building. The Royal Circle was a premier African-American social organization. It held annualcotillion

The cotillion (also cotillon or French country dance) is a social dance, popular in 18th-century Europe and North America. Originally for four couples in square formation, it was a courtly version of an English country dance, the forerunner ...

s for young African-American women through the early 1960s, at which they were "introduced" to adult society. Formed in 1918, the War Camp Community Service became the local American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is a non-profit organization of U.S. war veterans headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is made up of state, U.S. territory, and overseas departments, and these are in turn made up of ...

the following year. The Centralized Commonwealth Civic Club, formed in 1937, promoted community business. Two local Boy Scout

A Scout (in some countries a Boy Scout, Girl Scout, or Pathfinder) is a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement. Because of the large age and development span, many Scouting associations have split ...

troops (Troop 23, Troop 79) were founded for African-American youth.

The community also boasted halls for the Odd Fellows, the Masons, (which had about 550 members in North Omaha in 1936), and the Elks

The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (BPOE; also often known as the Elks Lodge or simply The Elks) is an American fraternal order founded in 1868, originally as a social club in New York City.

History

The Elks began in 1868 as a soci ...

, (with about 250 members in the community in 1936). Perhaps the most elusive organization in North Omaha was the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, also known as the "Knights of Liberty". This was a secret African-American organization whose goal was "nothing less than the destruction of slavery."

Historic entertainment venues

From the 1920s through to the early 1960s,North Omaha

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the ...

boasted a vibrant African-American entertainment district, featuring both local and nationally known musicians. The most important venue in the area was the Dreamland Ballroom

The Jewell Building is a city landmark in North Omaha, Nebraska. Built in 1923, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Located at 2221 North 24th Street, the building was home to the Dreamland Ballroom for more than 40 years, a ...

, opened in 1923 in the Jewell Building

The Jewell Building is a city landmark in North Omaha, Nebraska. Built in 1923, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Located at 2221 North 24th Street, the building was home to the Dreamland Ballroom for more than 40 years, a ...

at 24th and Grant Streets. Dreamland hosted some of the greatest jazz, blues, and swing performers, including Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was bas ...

, Count Basie

William James "Count" Basie (; August 21, 1904 – April 26, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, organist, bandleader, and composer. In 1935, he formed the Count Basie Orchestra, and in 1936 took them to Chicago for a long engagement and the ...

, Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and Singing, vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and se ...

, Lionel Hampton

Lionel Leo Hampton (April 20, 1908 – August 31, 2002) was an American jazz vibraphonist, pianist, percussionist, and bandleader. Hampton worked with jazz musicians from Teddy Wilson, Benny Goodman, and Buddy Rich, to Charlie Parker, Charles ...

, and the original Nat King Cole Trio. Whitney Young spoke there as well. Other venues included Jim Bell's Harlem, opened in 1935 on Lake Street, west of 24th; McGill's Blue Room, located at 24th and Lake, and; Allen's Showcase Lounge, which was located at 24th and Lake.

The Ritz Theater was opened in the mid-1930s at 2041 North 24th Street, near Patrick Avenue. It was specifically designated an "African-American theater" with seating for 548 people. It was closed in the 1950s and has since been demolished.

During this period, North Omaha and its main artery of

During this period, North Omaha and its main artery of North 24th Street

North 24th Street is a two-way street that runs south–north in the North Omaha area of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. With the street beginning at Dodge Street, the historically significant section of the street runs from Cuming Street to Ame ...

were the heart of the city's African-American cultural and business community, with a thriving jazz and rhythm & blues scene that attracted top-flight swing

Swing or swinging may refer to:

Apparatus

* Swing (seat), a hanging seat that swings back and forth

* Pendulum, an object that swings

* Russian swing, a swing-like circus apparatus

* Sex swing, a type of harness for sexual intercourse

* Swing ri ...

, blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the ...

and jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

bands from across the country. Due to racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

, musicians such as Cab Calloway

Cabell Calloway III (December 25, 1907 – November 18, 1994) was an American singer, songwriter, bandleader, conductor and dancer. He was associated with the Cotton Club in Harlem, where he was a regular performer and became a popular vocalis ...

stayed at Myrtle Washington's at 22nd and Willis, while others stayed at Charlie Trimble's at 22nd and Seward. Early North Omaha bands included Lewis' Excelsior Brass Band, Dan Desdunes

Daniel F. Desdunes (c. 1870 – April 24, 1929) was a civil rights activist and musician in New Orleans and Omaha, Nebraska.

Descended from a family of free people of color, people of color free before the Civil War, in 1892 he volunteered to ...

Band, Simon Harrold's Melody Boys, the Sam Turner Orchestra, the Ted Adams Orchestra, the Omaha Night Owls, Red Perkins

Frank Shelton "Red" Perkins (December 26, 1890 – September 27, 1976) was an American jazz trumpet player, singer, and bandleader. Perkins led of one of the oldest Omaha, Nebraska-based jazz territory bands, The Dixie Ramblers, and saw his gre ...

and his Original Dixie Ramblers, and the Lloyd Hunter

Lloyd Hunter (May 4, 1910–month and date unknown, 1961) was an American trumpeter and big band leader from North Omaha, Nebraska.(nd"Jammin’ For the Jackpot: Big Bands and Territory Bands of the 30s" New World Records, p. 10. .

Biography

Hunt ...

Band who, in 1931, became the first Omaha band to record. A Lloyd Hunter concert poster can be seen on display at the Community Center in nearby Mineola, Iowa.

The intersection of 24th and Lake was the setting of the Big Joe Williams

Joseph Lee "Big Joe" Williams (October 16, 1903 – December 17, 1982) was an American Delta blues guitarist, singer and songwriter, notable for the distinctive sound of his nine-string guitar. Performing over five decades, he recorded the s ...

song "Omaha Blues". Omaha-born Wynonie Harris

Wynonie Harris (August 24, 1915 – June 14, 1969) was an American blues shouter and rhythm-and-blues singer of upbeat songs, featuring humorous, often ribald lyrics. He had fifteen Top 10 hits between 1946 and 1952. Harris is attributed by ...

, one of the founders of rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm ...

, got his start at the North Omaha clubs, and for a time lived in the now-demolished Logan Fontenelle Housing Project The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project was a historic public housing site located from 20th to 24th Streets, and from Paul to Seward Streets in the historic Near North Side neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was built in 1938 by the P ...

. There were many African-American churches, social and civic clubs, formal dances for young people, and many other cultural activities.

Several accounts attribute the decline of the African-American cultural scene in North Omaha to the riots of the 1960s and 70s. Television also took away from local entertainment. Since the turn of the 21st century, there has been a resurgence in interest in this vibrant period, with cultural and historical institutions created to honor it, such as Love's Jazz & Art Center, the Dreamland Project, and the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame.

Historic musicians

Preston Love

Preston Haynes Love (April 26, 1921 – February 12, 2004) was an American saxophonist, bandleader, and songwriter from Omaha, Nebraska, United States, best known as a sideman for jazz and rhythm and blues artists like Count Basie and Ray Char ...

, who left Omaha to tour nationally, said,

The history of African Americans and music in Omaha is long and varied. The black music community was first organized in the early 20th century by Josiah Waddle, one of Omaha's first barbers. After teaching himself to play a number of brass instrument

A brass instrument is a musical instrument that produces sound by sympathetic vibration of air in a tubular resonator in sympathy with the vibration of the player's lips. Brass instruments are also called labrosones or labrophones, from Latin a ...

s, Waddle pulled together Omaha's first African American band in 1902. In 1917 he brought together the first women's band in Omaha. One of his most famous students was Lloyd Hunter

Lloyd Hunter (May 4, 1910–month and date unknown, 1961) was an American trumpeter and big band leader from North Omaha, Nebraska.(nd"Jammin’ For the Jackpot: Big Bands and Territory Bands of the 30s" New World Records, p. 10. .

Biography

Hunt ...

, who ran one of the most popular orchestras' in the United States Midwest. Anna Mae Winburn was a student of Waddle's as well.

After leading the Cotton Club Boys and several smaller outfits, Winburn led the International Sweethearts of Rhythm

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm was the first integrated all-women's band in the United States. During the 1940s the band featured some of the best female musicians of the day. They played swing and jazz on a national circuit that incl ...

to fame during World War II. The Sweethearts were the first integrated all women's band in the United States. Nat Towles

Nat Towles (August 10, 1905 – January 1963) was an American musician, jazz and big band leader popular in his hometown of New Orleans, Louisiana, North Omaha, Nebraska and Chicago, Illinois. He was also music educator in Austin, Texas. The ...

also led an important territory band out of Omaha during the swing era

The swing era (also frequently referred to as the big band era) was the period (1933–1947) when big band swing music was the most popular music in the United States. Though this was its most popular period, the music had actually been arou ...

, and most of these bands were represented by the National Orchestra Service The National Orchestra Service, Inc. (NOS), was the most important booking and management agency for territory bands across the Great Plains and other regions from the early 1930s through 1960. NOS managed black, white and integrated orchestras and ...

, which was also based out of Omaha. It was a nationally regarded company which acted as agent for dozens of bands.

International Jazz legend Preston Love

Preston Haynes Love (April 26, 1921 – February 12, 2004) was an American saxophonist, bandleader, and songwriter from Omaha, Nebraska, United States, best known as a sideman for jazz and rhythm and blues artists like Count Basie and Ray Char ...

was an important figure in Omaha's African-American community. After playing in Towles' and Hunter's bands, Love joined Count Basie

William James "Count" Basie (; August 21, 1904 – April 26, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, organist, bandleader, and composer. In 1935, he formed the Count Basie Orchestra, and in 1936 took them to Chicago for a long engagement and the ...

as a saxophonist. After traveling the world, Love came back to North Omaha and founded his own band. He also joined the staff of the '' Omaha Star'' newspaper. Love toured the U.S. and Europe into the late 1990s and died in 2004.

North Omaha's musical culture gave rise to several influential African-American musicians. Rhythm & Blues singer Wynonie Harris

Wynonie Harris (August 24, 1915 – June 14, 1969) was an American blues shouter and rhythm-and-blues singer of upbeat songs, featuring humorous, often ribald lyrics. He had fifteen Top 10 hits between 1946 and 1952. Harris is attributed by ...

and influential drummer Buddy Miles, who played with guitarist Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, singer and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most ...

, were friends while they grew up and played together. They collaborated throughout their lives, and while they were playing with the greatest names in rock and roll, jazz, R&B andfFunk. Big Joe Williams

Joseph Lee "Big Joe" Williams (October 16, 1903 – December 17, 1982) was an American Delta blues guitarist, singer and songwriter, notable for the distinctive sound of his nine-string guitar. Performing over five decades, he recorded the s ...

and funk band leader Lester Abrams

Lester Abrams (born 1945) is a singer, songwriter, musician and producer who has played with such artists as B.B. King, Stevie Wonder, Peabo Bryson, Quincy Jones, Manfred Mann, Brian Auger, The Average White Band, The Doobie Brothers, Rufus and m ...

are also from North Omaha.

Historic newspapers

There have been numerous African-American newspapers in Omaha. The first was the ''Progress'', established in 1889 by Ferdinand L. Barnett.Cyrus D. Bell

Cyrus Dicks Bell (August 1848 - October 21, 1925) was a journalist, civil rights activist, and civic leader in Omaha, Nebraska. He owned and edited the black newspaper ''Afro-American Sentinel'' during the 1890s. He was an outspoken political i ...

, an ex-slave, established the ''Afro-American Sentinel'' in 1892. In 1893 George F. Franklin started publishing the ''Enterprise,'' later published by Thomas P. Mahammitt and edited by his wife, Ella Mahammitt

Ella Lillian Davis Browne Mahammitt (November 22, 1863 – September 9, 1932) was an American journalist, civil rights activist, and women's rights activist from Omaha, Nebraska. She was editor of the black weekly '' The Enterprise'', president ...

. It was the longest lived of any of the early African-American newspapers published in Omaha. The best known and most widely read of all African-American newspapers in the city was the ''Omaha Monitor'', established in 1915, edited and published by Reverend John Albert Williams

John Albert Williams (February 28, 1866 – February 4, 1933) was a minister, journalist, and political activist in Omaha, Nebraska. He was born to an escaped slave and spoke from the pulpit and the newspapers on issues of civil rights, equalit ...

. It stopped publishing in 1929.

George Wells Parker

George Wells Parker (September 18, 1882 – July 28, 1931) was an African-American political activist, historian, public intellectual, and writer who co-founded the Hamitic League of the World.

Biography

George Wells Parker's parents were b ...

, co-founder of the Hamitic League of the World, founded the ''New Era'' in Omaha from 1920 through until 1926. The ''Omaha Guide'' was established by B.V. and C.C. Galloway in 1927. The ''Guide'', with a circulation of over 25,000 and an advertisers' list including business firms from coast to coast, was the largest African-American newspaper west of the Missouri River through the 1930s.

Today, African-American culture in Omaha is regarded as being anchored, in large part, by ''The Omaha Star

''The'' ''Omaha Star'' is a newspaper founded in 1938 in North Omaha, Nebraska, by Mildred Brown and her husband S. Edward Gilbert. Housed in the historic Omaha Star building in the Near North Side neighborhood, today the ''Omaha Star'' is the on ...

'', founded by the late Mildred D. Brown and her husband S. E. Gilbert in 1938. Brown is believed to be the first female, and certainly the first African-American woman, to have founded a newspaper in the nation's history. She managed the paper for the rest of her life. Since 1945 the paper was the only one representing the black community in Omaha and the only black paper being printed in the state. Today the paper has a circulation of more than 30,000, is distributed to the 48 continental states, and is being managed by her niece.

Other cultural institutions

TheFair Deal Cafe

Fair Deal Cafe was a historically significant diner for the African American community in North Omaha, Nebraska. Once known as the "Black City Hall", Fair Deal was located at North 24th & Burdette in the Near North Omaha neighborhood from 1954 - ...

, located on North 24th Street, was called the "Black City Hall" during its existence from 1954 to 2003. Today, Omaha's African-American community celebrates its heritage in numerous ways. The biennial Native Omahans Days is a week-long celebration including picnics, family reunions and a large parade. Also held on a biennial calendar is the induction ceremony for the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame, or OBMHoF. Their inductees include African American contributors to rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm ...

, swing

Swing or swinging may refer to:

Apparatus

* Swing (seat), a hanging seat that swings back and forth

* Pendulum, an object that swings

* Russian swing, a swing-like circus apparatus

* Sex swing, a type of harness for sexual intercourse

* Swing ri ...

, jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

and R&B, as well as other cultural contributions.

Formed by Bertha Calloway in the 1960s, the Negro Historical Society opened the Great Plains Black Museum in North Omaha in 1974. Located at 2213 Lake Street, the museum is home to Omaha's only African-American history collection. The annual Omaha Jazz and Blues Festival also promotes African-American culture throughout the city.

Race relations

North Omaha has a contentious history between whites and African Americans that is predicated on racism. In 1891 an African American George Smith was lynched at the Douglas County Courthouse, accused as a suspect for allegedly attacking a young girl. While little is known about Smith, reports of the incident described a mob dragging Smith from his cell, before any court trial, and hanging him from a nearby street post. In July 1910 racial tension flared towards the African-American community after a tremendous upset victory by African-American boxer Jack Johnson inReno, Nevada

Reno ( ) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada-California border, about north from Lake Tahoe, known as "The Biggest Little City in the World". Known for its casino and tourism industry, Reno is th ...

. Mobs of whites roamed throughout Omaha rioting, as they did in cities across the U.S. The mobs wounded several black men in the city, killing one.

The Red Summer of 1919

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civi ...

caused one Omaha newspaper to run a front page declaration that 21 Omaha women reported that they were assaulted from early June to late September 1919. In an example of yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

, 20 of the victims were white and 16 of the assailants were identified as black, while only one of the victims was black. A separate newspaper warned that vigilante committees would be formed if the "respectable colored population could not purge those from the Negro community who were assaulting white girls." During the ensuing Omaha Race Riot of 1919

The Omaha Race Riot occurred in Omaha, Nebraska, September 28–29, 1919. The race riot resulted in the lynching of Will Brown, a black civilian; the death of two white rioters; the injuries of many Omaha Police Department officers and civili ...

in September, a white ethnic mob from South Omaha took over the Douglas County Courthouse. The white rioters lynched Willy Brown, an accused packinghouse worker. They then tried to attack blacks on the street and move against the community in North Omaha. Soldiers from Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

put down the riot. They reestablished control and were stationed in South Omaha, to prevent any more mobs from forming, and in North Omaha at 24th and Lake streets "to prevent any further murders of black citizens. Orders were issued that any citizen with a gun faced immediate arrest. All blacks were ordered to remain indoors."

Segregation

A legacy of this terrible summer was the de factoracial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

of many of Omaha's neighborhoods. Introduced in the 1930s, the practices of redlining

In the United States, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which services ( financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as "hazardous" to investment; these neighborhoods have sign ...

by banks and racially restrictive housing covenants effectively ended for decades the ability of African Americans to buy or rent outside North Omaha. Originally built in the 1930s, Omaha housing projects were intended for occupancy without reference to race. A 1937 report from the Omaha Housing Authority

Omaha Housing Authority, or OHA, is the government agency responsible for providing public housing in Omaha, Nebraska. It is the parent organization of Housing in Omaha, Inc., a nonprofit housing developer for low-income housing.

About

OHA contr ...

reported that residents included "both black and white occupants and there are 284 units. There is no distinct segregation of the whites from the blacks but individual buildings will be confined to either Negro or white." The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project was a historic public housing site located from 20th to 24th Streets, and from Paul to Seward Streets in the historic Near North Side neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was built in 1938 by the P ...

, built during the Depression, with an addition completed in 1941, to improve working class housing in North Omaha, was closed to African Americans through the 1950s. Even in the 1940s, housing was so overcrowded in the area that some families stayed at the projects although their income exceeded the limits, because they couldn't find housing elsewhere. With civil rights challenges, the segregation policy that kept African Americans out of public housing changed in the 1960s.

The massive loss of industrial jobs changed the nature of families and the issues in public housing. Although the Logan Fontenelle projects were first built for working families, they came to be dominated by the unemployed. Other public housing projects also reflected later de facto segregation. A concentration of problems here and in other cities led the City of Omaha, along with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government. It administers federal housing and urban development laws. It is headed by the Secretary of Housing and Ur ...

, to radically rethink public housing in the 1990s. The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project The Logan Fontenelle Housing Project was a historic public housing site located from 20th to 24th Streets, and from Paul to Seward Streets in the historic Near North Side neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was built in 1938 by the P ...

was torn down in 1996. Today public housing is scattered throughout Omaha and often combined with market rate housing and community amenities.

Civil Rights Movement

The lynching of Willy Brown has been credited for radicalizingOmaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest c ...

's African-American community. In the 1920s the Omaha chapter of Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

's Universal Negro Improvement Association

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-Africa ...

was founded by Earl Little, a Baptist minister and the father of Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

. Malcolm X was born in Omaha in 1925. Malcolm X's mother reported a 1924 incident where her family was warned to leave Omaha by Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

smen. She was told that her husband, Earl Little, was "stirring up trouble" through his involvement with Universal Negro Improvement Association

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-Africa ...

. The family moved shortly thereafter.

Another radical leader, Communist spokesman and one-time leader of American forces in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

Harry Haywood

Harry Haywood (February 4, 1898 – January 4, 1985) was an American political activist who was a leading figure in both the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). His goal was to connect ...

, was born in 1898 in South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

as Haywood Hall to parents who were former slaves. In 1913 his father was beaten by a white gang at the South Omaha meatpacking plant where he worked, forcing the family to move from the city. The African Blood Brotherhood, started in Omaha, contributed to radicalizing Haywood when he joined it the group in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, where his family had moved in 1915.

Starting in 1920, the Colored Commercial Club organized to help blacks in Omaha secure employment and to encourage business enterprises among African Americans. The National Federation of Colored Women had five chapters in Omaha. In 1927 the first

Starting in 1920, the Colored Commercial Club organized to help blacks in Omaha secure employment and to encourage business enterprises among African Americans. The National Federation of Colored Women had five chapters in Omaha. In 1927 the first Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

chapter (now the Urban League of Nebraska) in the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

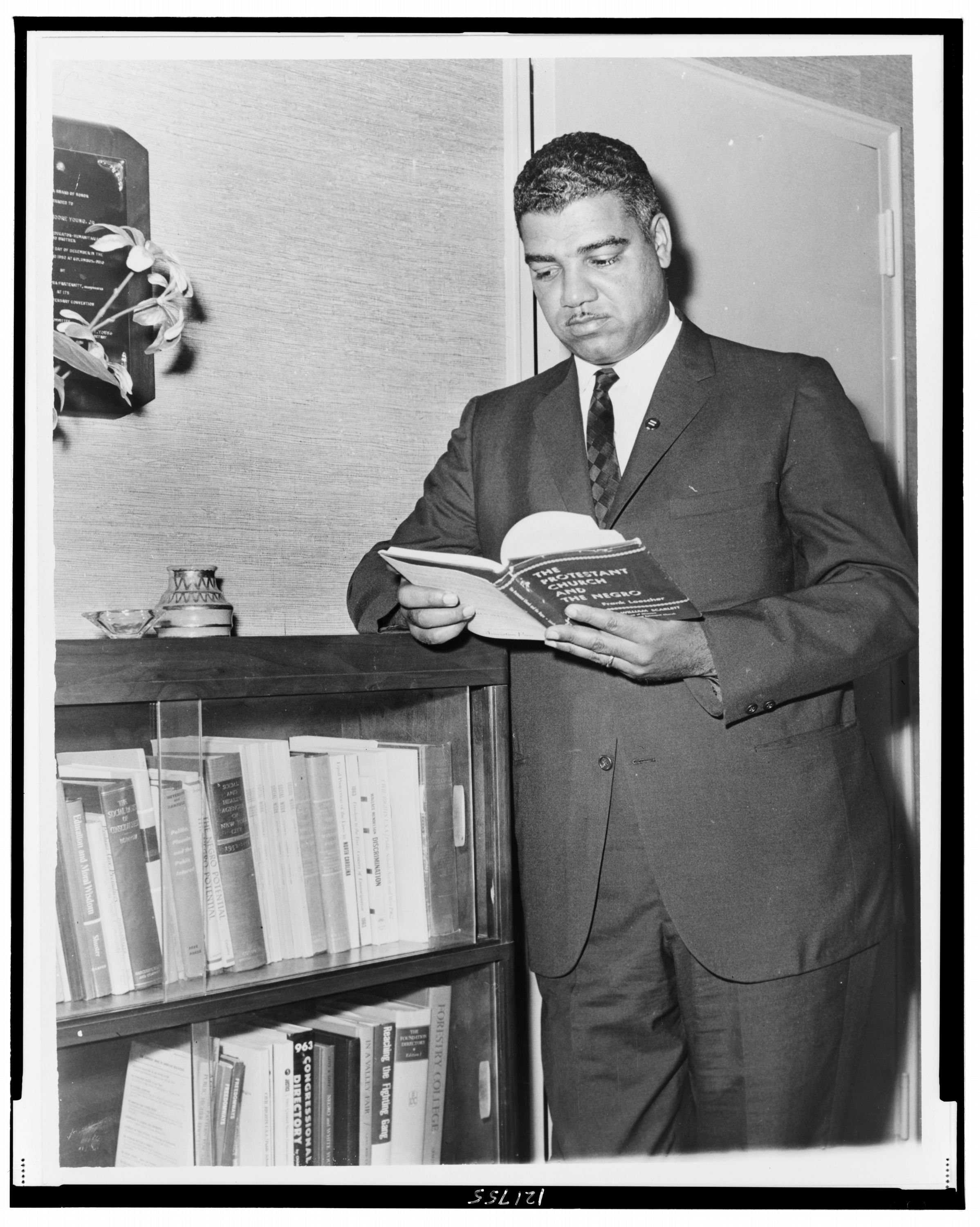

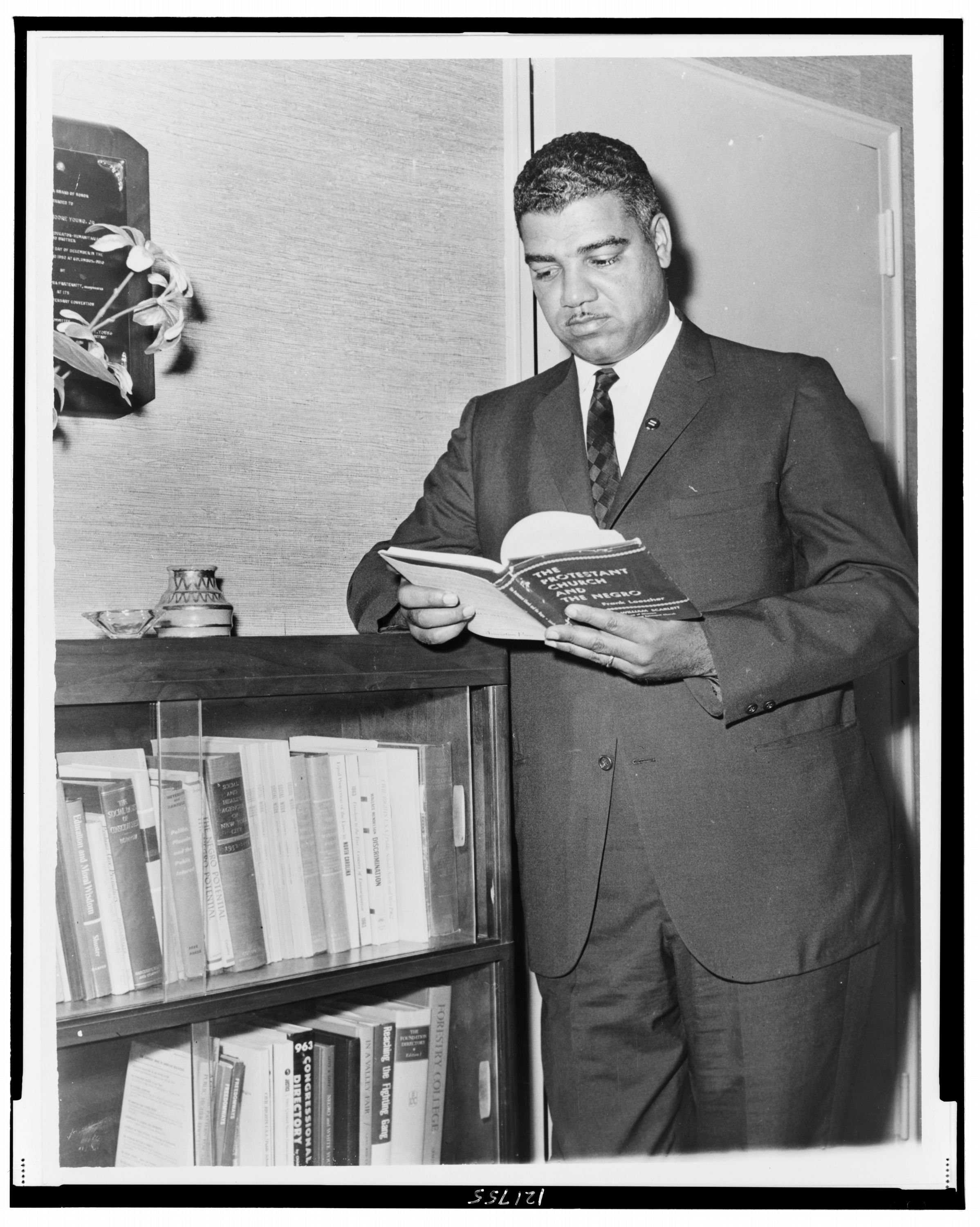

was founded in the city. Whitney Young led the chapter in 1950, tripling its membership. Eventually, he would take over the national leadership of the Urban League in 1961.

The Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

organized African-American workers in the South Omaha South Omaha is a former city and current district of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. During its initial development phase the town's nickname was "The Magic City" because of the seemingly overnight growth, due to the rapid development of the Union S ...

Stockyards in the 1920s. Along with the rest of the working class, they suffered setbacks during layoffs in the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, however, an interracial committee succeeded in organizing the United Meatpacking Workers of America, one of the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

(CIO) unions. They worked to end segregation of job positions in meatpacking in the 1940s. Community leader Rowena Moore attacked gender restrictions and organized to expand opportunities in industry for black women. UMPWA helped African Americans extend their political power and gain an end to segregation in retail places in the 1950s. After all this progress, however, the loss of more than 10,000 jobs due to structural changes in the railroad and meatpacking industries in the 1960s sharply reduced opportunities for the working-class communities.

In 1952, Arthur B. McCaw became the first African American to be appointed to a cabinet level position in the Nebraska governor's office, budget director of the state of Nebraska in 1952. Prior to that he had been active in Omaha civil rights and was an assessor and on the tax appraisal board of Douglas County. In 1955 he was Nebraska state chairman of the NAACP and helped form a Lincoln chapter of the organization.

As a major western city, Omaha was visited by Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

in 1958 and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, who helped galvanize the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

in North Omaha. Local leaders continued to struggle against racism.Distilled in Black and White''Omaha Reader''. Retrieved July 26, 2007. North Omaha was marred by race-related violence and de facto segregation throughout the 20th century. When the

Black Panthers

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxist-Leninist and black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, Califo ...

were implicated in a police killing in North Omaha in 1970, the trial highlighted political tensions. The Rice–Poindexter case David Rice (1947 – March 11, 2016) (also known as Mondo we Langa) and Edward Poindexter were charged and convicted of the murder of Omaha Police Officer Larry Minard. Minard died when a suitcase bomb containing dynamite exploded in a North Omaha ...

continues to highlight Omaha's contentious legacy of racism. As of 2017, a majority of Omaha's African-American population still lives in North Omaha.

Integration

Studies have shown starting in the 1950s Omaha's white middle class moved from North Omaha to the suburbs of West Omaha in the phenomenon called "white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

."Caldas, S. J., and C. L. Bankston (2003), The End of Desegregation?

' Nova Science Publishers, p. 12. The inability of government money to solve the problems of Omaha's African American community was accented by white flight. The city's schools were greatly affected by racial unrest. Consequential to the 1971 ''

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education