African American culture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

African-American culture refers to the contributions of African Americans to the culture of the United States, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. The culture is both distinct and enormously influential on American and global worldwide culture as a whole.

African-American culture is a blend between the native African cultures of

African-American culture refers to the contributions of African Americans to the culture of the United States, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. The culture is both distinct and enormously influential on American and global worldwide culture as a whole.

African-American culture is a blend between the native African cultures of

From the earliest days of

From the earliest days of

The first major public recognition of African-American culture occurred during the Harlem Renaissance pioneered by

The first major public recognition of African-American culture occurred during the Harlem Renaissance pioneered by

Hip hop and contemporary R&B would become a multicultural movement, however, it still remained important to many African Americans. The African-American Cultural Movement of the 1960s and 1970s also fueled the growth of funk and later hip hop forms such as

Hip hop and contemporary R&B would become a multicultural movement, however, it still remained important to many African Americans. The African-American Cultural Movement of the 1960s and 1970s also fueled the growth of funk and later hip hop forms such as

African-American dance, like other aspects of African-American culture, finds its earliest roots in the dances of the hundreds of African ethnic groups that made up the enslaved African population in the Americas as well as in traditional folk dances from Europe. Dance in the African tradition, and thus in the tradition of slaves, was a part of both everyday life and special occasions. Many of these traditions such as get down,

African-American dance, like other aspects of African-American culture, finds its earliest roots in the dances of the hundreds of African ethnic groups that made up the enslaved African population in the Americas as well as in traditional folk dances from Europe. Dance in the African tradition, and thus in the tradition of slaves, was a part of both everyday life and special occasions. Many of these traditions such as get down,

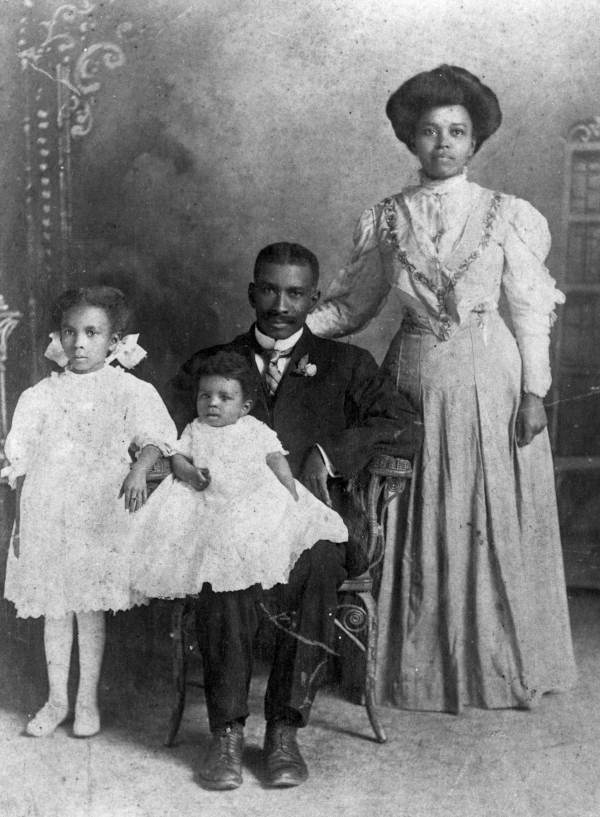

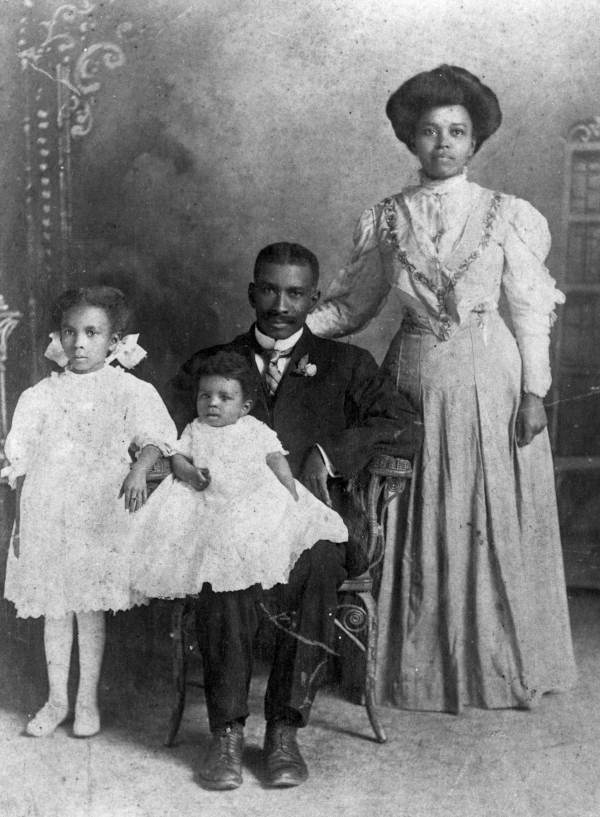

From its early origins in slave communities, through the end of the 20th century, African-American art has made a vital contribution to the art of the United States. During the period between the 17th century and the early 19th century, art took the form of small drums, quilts, wrought-iron figures, and ceramic vessels in the southern United States. These artifacts have similarities with comparable crafts in West and Central Africa. In contrast, African-American artisans like the New England–based engraver Scipio Moorhead and the Baltimore portrait painter Joshua Johnson created art that was conceived in a thoroughly western European fashion.

During the 19th century, Harriet Powers made quilts in rural Georgia, United States that are now considered among the finest examples of 19th-century Southern quilting. Later in the 20th century, the women of Gee's Bend developed a distinctive, bold, and sophisticated quilting style based on traditional African-American quilts with a geometric simplicity that developed separately but was like that of Amish quilts and modern art.

After the

From its early origins in slave communities, through the end of the 20th century, African-American art has made a vital contribution to the art of the United States. During the period between the 17th century and the early 19th century, art took the form of small drums, quilts, wrought-iron figures, and ceramic vessels in the southern United States. These artifacts have similarities with comparable crafts in West and Central Africa. In contrast, African-American artisans like the New England–based engraver Scipio Moorhead and the Baltimore portrait painter Joshua Johnson created art that was conceived in a thoroughly western European fashion.

During the 19th century, Harriet Powers made quilts in rural Georgia, United States that are now considered among the finest examples of 19th-century Southern quilting. Later in the 20th century, the women of Gee's Bend developed a distinctive, bold, and sophisticated quilting style based on traditional African-American quilts with a geometric simplicity that developed separately but was like that of Amish quilts and modern art.

After the

The African-American Museum Movement emerged during the 1950s and 1960s to preserve the heritage of the African-American experience and to ensure its proper interpretation in American history. Museums devoted to

The African-American Museum Movement emerged during the 1950s and 1960s to preserve the heritage of the African-American experience and to ensure its proper interpretation in American history. Museums devoted to

The Black Arts Movement, a cultural explosion of the 1960s, saw the incorporation of surviving cultural dress with elements from modern fashion and West African traditional clothing to create a uniquely African-American traditional style.

The Black Arts Movement, a cultural explosion of the 1960s, saw the incorporation of surviving cultural dress with elements from modern fashion and West African traditional clothing to create a uniquely African-American traditional style.

Hair styling in African-American culture is greatly varied. African-American hair is typically composed of coiled curls, which range from tight to wavy. Many women choose to wear their hair in its natural state. Natural hair can be styled in a variety of ways, including the afro, twist outs, braid outs, and wash and go styles. It is a myth that natural hair presents styling problems or is hard to manage; this myth seems prevalent because mainstream culture has, for decades, attempted to get African-American women to conform to its standard of beauty (i.e., straight hair). To that end, some women prefer straightening of the hair through the application of heat or chemical processes. Although this can be a matter of personal preference, the choice is often affected by straight hair being a beauty standard in the West and the fact that hair type can affect employment. However, more and more women are wearing their hair in its natural state and receiving positive feedback. Alternatively, the predominant and most socially acceptable practice for men is to leave one's hair natural.

Often, as men age and begin to lose their hair, the hair is either closely cropped, or the head is shaved completely free of hair. However, since the 1960s,

Hair styling in African-American culture is greatly varied. African-American hair is typically composed of coiled curls, which range from tight to wavy. Many women choose to wear their hair in its natural state. Natural hair can be styled in a variety of ways, including the afro, twist outs, braid outs, and wash and go styles. It is a myth that natural hair presents styling problems or is hard to manage; this myth seems prevalent because mainstream culture has, for decades, attempted to get African-American women to conform to its standard of beauty (i.e., straight hair). To that end, some women prefer straightening of the hair through the application of heat or chemical processes. Although this can be a matter of personal preference, the choice is often affected by straight hair being a beauty standard in the West and the fact that hair type can affect employment. However, more and more women are wearing their hair in its natural state and receiving positive feedback. Alternatively, the predominant and most socially acceptable practice for men is to leave one's hair natural.

Often, as men age and begin to lose their hair, the hair is either closely cropped, or the head is shaved completely free of hair. However, since the 1960s,

"The Most Endangered Title VII Plaintiff?: African-American Males and Intersectional Claims"

''Nebraska Law Review'', Vol. 86, No. 3, 2008, pp. 14–15. Retrieved November 8, 2007. In fact, the soul patch is so named because African-American men, particularly jazz musicians, popularized the style. The preference for facial hair among African-American men is due partly to personal taste, but also because they are more prone than other ethnic groups to develop a condition known as ''

The religious institutions of African-American Christians are commonly and collectively referred to as the

The religious institutions of African-American Christians are commonly and collectively referred to as the

Judaism Drawing More Black Americans

''

In studying of the African American culture, food cannot be left out as one of the mediums to understand their traditions, religion, interaction, and social and cultural structures of their community. Observing the ways they prepare their food and eat their food ever since the enslaved era, reveals about the nature and identity of African American culture in the United States. Derek Hicks examines the origins of "

In studying of the African American culture, food cannot be left out as one of the mediums to understand their traditions, religion, interaction, and social and cultural structures of their community. Observing the ways they prepare their food and eat their food ever since the enslaved era, reveals about the nature and identity of African American culture in the United States. Derek Hicks examines the origins of " The cultivation and use of many agricultural products in the United States, such as yams,

The cultivation and use of many agricultural products in the United States, such as yams,

As with other American racial and ethnic groups, African Americans observe ethnic holidays alongside traditional American holidays. Holidays observed in African-American culture are not only observed by African Americans but are widely considered American holidays. The birthday of noted American

As with other American racial and ethnic groups, African Americans observe ethnic holidays alongside traditional American holidays. Holidays observed in African-American culture are not only observed by African Americans but are widely considered American holidays. The birthday of noted American

When slavery was practiced in the United States, it was common for

When slavery was practiced in the United States, it was common for

The Black LGBT community refers to the African-American (Black) population who are members of the LGBT community, as a community of marginalized individuals who are further marginalized within their own community. Surveys and research have shown that 80% of African Americans say gays and lesbians endure discrimination compared to the 61% of whites. Black members of the community are not only seen as "other" due to their race, but also due to their sexuality, so they always had to combat racism and homophobia.

Black LGBT first started to be visible during the Harlem Renaissance when a subculture of LGBTQ African-American artists and entertainers emerged. This included people like

The Black LGBT community refers to the African-American (Black) population who are members of the LGBT community, as a community of marginalized individuals who are further marginalized within their own community. Surveys and research have shown that 80% of African Americans say gays and lesbians endure discrimination compared to the 61% of whites. Black members of the community are not only seen as "other" due to their race, but also due to their sexuality, so they always had to combat racism and homophobia.

Black LGBT first started to be visible during the Harlem Renaissance when a subculture of LGBTQ African-American artists and entertainers emerged. This included people like

/ref>

African-American neighborhoods are types of

African-American neighborhoods are types of

There are African American social networking websites such as

There are African American social networking websites such as

African-American culture refers to the contributions of African Americans to the culture of the United States, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. The culture is both distinct and enormously influential on American and global worldwide culture as a whole.

African-American culture is a blend between the native African cultures of

African-American culture refers to the contributions of African Americans to the culture of the United States, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. The culture is both distinct and enormously influential on American and global worldwide culture as a whole.

African-American culture is a blend between the native African cultures of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

and Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

and the European culture

The culture of Europe is rooted in its art, architecture, film, different types of music, economics, literature, and philosophy. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".

Definition ...

that has influenced and modified its development in the American South. Understanding its identity within the culture of the United States, that is, in the anthropological sense, conscious of its origins as largely a blend of West and Central African cultures. Although slavery greatly restricted the ability for Africans to practice their original cultural traditions, many practices, values and beliefs survived, and over time they have modified and/or blended with European cultures and other cultures such as that of Native Americans. African-American identity was established during the period of slavery, producing a dynamic culture that has had and continues to have a profound impact on American culture as a whole, as well as that of the broader world.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

has played a defining role in African-American culture. In late 18th century Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

for example, the black church

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as their ...

was born out of protest and revolutionary reaction to racism by freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

whom resented being relegated to a segregated gallery. This was as custom in the Antebellum South for slaves whom generally attended their masters' white churches.Clayborn Carson, Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner, and Gary B. Nash, ''The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans, Vol 1 to 1877'' (Prentice Hall, 2012), p. 18. The black church is regarded as the center of the American civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

in that it also served as the “ symbol of the movement”.

After emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

, unique African-American traditions have continued to flourish, as distinctive traditions or radical innovations in music, art, literature, religion, cuisine, and other fields. 20th-century sociologists believe that African-Americans have lost most of their cultural ties with Africa. Influence however of African traditions and cultural practices on European culture for example, may be found in the American South below the Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virginia ...

.African-American culture is also part of the culture of the Southern as well as Northern regions of the United States. Black American food and language is influenced by white Southerners

White Southerners, from the Southern United States, are considered an ethnic group by some historians, sociologists and journalists, although this categorization has proven controversial, and other academics have argued that Southern identity do ...

who enslaved them on plantations in the South.

For many years African-American culture developed separately from American culture

The culture of the United States of America is primarily of Western, and European origin, yet its influences includes the cultures of Asian American, African American, Latin American, and Native American peoples and their cultures. The U ...

, due to enslavement, racial discrimination, and the persistence of African-Americans to make and maintain their own traditions. Today, African-American culture has influenced American culture and yet still remains a distinct cultural body.

African-American cultural history

From the earliest days of

From the earliest days of American slavery

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slaver ...

in the 17th century, slave owners sought to exercise control over their slaves by attempting to strip them of their African culture

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

. The physical isolation and societal marginalization of African slaves and, later, of their free progeny, however, facilitated the retention of significant elements of traditional culture among Africans in the New World generally, and in the United States in particular. Slave owners deliberately tried to repress independent political or cultural organization in order to deal with the many slave rebellions or acts of resistance that took place in the United States, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Haiti, and the Dutch Guyanas.

African cultures, slavery, slave rebellions, and the civil rights movement have shaped African-American religious, familial, political, and economic behaviors. The imprint of Africa is evident in a myriad of ways: in politics, economics, language, music, hairstyles, fashion, dance, religion, cuisine, and worldview.

In turn, African-American culture has had a pervasive, transformative impact on many elements of mainstream American culture. This process of mutual creative exchange is called creolization

Creolization is the process through which creole languages and cultures emerge. Creolization was first used by linguists to explain how contact languages become creole languages, but now scholars in other social sciences use the term to describe ne ...

. Over time, the culture of African slaves and their descendants has been ubiquitous in its impact on not only the dominant American culture, but on world culture as well.

Oral tradition

The Slaveholders limited or prohibited education of enslaved African-Americans because they feared it might empower their chattel and inspire or enable emancipatory ambitions. In the United States, the legislation that denied slaves formal education likely contributed to their maintaining a strong oral tradition, a common feature of indigenous or native African culture. African-based oral traditions became the primary means of preserving history, mores, and other cultural information among the people. This was consistent with the ''griot

A griot (; ; Manding: jali or jeli (in N'Ko: , ''djeli'' or ''djéli'' in French spelling); Serer: kevel or kewel / okawul; Wolof: gewel) is a West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet, and/or musician.

The griot is a repos ...

'' practices of oral history in many native African culture and other cultures that did not rely on the written word. Many of these cultural elements have been passed from generation to generation through storytelling. The folktales provided African-Americans the opportunity to inspire and educate one another.

Examples of African American folktales include trickster

In mythology and the study of folklore and religion, a trickster is a character in a story ( god, goddess, spirit, human or anthropomorphisation) who exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge and uses it to play tricks or otherwi ...

tales of Br'er Rabbit

Br'er Rabbit (an abbreviation of ''Brother Rabbit'', also spelled Brer Rabbit) is a central figure in an oral tradition passed down by African-Americans of the Southern United States and African descendants in the Caribbean, notably Afro-Bahami ...

and hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''her ...

ic tales such as that of John Henry. The '' Uncle Remus'' stories by Joel Chandler Harris

Joel Chandler Harris (December 9, 1848 – July 3, 1908) was an American journalist, fiction writer, and folklorist best known for his collection of Uncle Remus stories. Born in Eatonton, Georgia, where he served as an apprentice on a planta ...

helped to bring African-American folk tales into mainstream adoption. Harris did not appreciate the complexity of the stories nor their potential for a lasting impact on society. Other narratives that appear as important, recurring motifs in African-American culture are the " Signifying Monkey", "The Ballad of Shine", and the legend of Stagger Lee.

The legacy of the African-American oral tradition manifests in diverse forms. African-American preachers tend to perform rather than simply speak. The emotion of the subject is carried through the speaker's tone, volume, and cadence, which tend to mirror the rising action, climax, and descending action of the sermon. The meaning of this manner of preaching is not easily understood by European Americans

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent E ...

or others of non-African origin. Often song, dance, verse, and structured pauses are placed throughout the sermon. Call and response

Call and response is a form of interaction between a speaker and an audience in which the speaker's statements ("calls") are punctuated by responses from the listeners. This form is also used in music, where it falls under the general category of ...

is another element of the African-American oral tradition. It manifests in worship in what is commonly referred to as the "amen corner". In direct contrast to the tradition present in American and European cultures, it is an acceptable and common audience reaction to interrupt and affirm the speaker. This pattern of interaction is also in evidence in music, particularly in blues and jazz forms. Hyperbolic and provocative, even incendiary, rhetoric is another aspect of African-American oral tradition often evident in the pulpit in a tradition sometimes referred to as "prophetic speech".

Modernity and migration of African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

communities to the North has had a history of placing strain on the retention of African American cultural practices and traditions. The urban and radically different spaces in which black culture was being produced raised fears in anthropologists and sociologists that the southern African American folk aspect of black popular culture were at risk of being lost within history. The study over the fear of losing black popular cultural roots from the South have a topic of interest to many anthropologists, who among them include Zora Neale Hurston. Through her extensive studies of Southern folklore and cultural practices, Hurston has claimed that the popular Southern folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

traditions and practices are not dying off. Instead they are evolving, developing, and re-creating themselves in different regions.

Other aspects of African-American oral tradition include the dozens

The Dozens is a game played between two contestants in which the participants insult each other until one of them gives up. Common in African-American communities, the Dozens is almost exclusively played in front of an audience, who encourage the ...

, signifying

Signifyin' (sometimes written "signifyin(g)") (vernacular), is a wordplay. It is a practice in African-American culture involving a verbal strategy of indirection that exploits the gap between the denotative and figurative meanings of words. A si ...

, trash talk

Trash talk is a form of insult usually found in sports events, although it is not exclusive to sports or similarly characterized events. It is often used to intimidate the opposition and/or make them less confident in their abilities as to win e ...

, rhyming, semantic inversion and word play, many of which have found their way into mainstream American popular culture and become international phenomena.Michael L. Hecht, Ronald L. Jackson, Sidney A. Ribeau (2003). ''African American Communication: Exploring Identity and Culture?'' Routledge. pp. 3–245.

Spoken-word poetry

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer's aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of ...

is another example of how the African-American oral tradition has influenced modern popular culture. Spoken-word artists employ the same techniques as African-American preachers including movement, rhythm, and audience participation. Rap music from the 1980s and beyond has been seen as an extension of African oral culture.

Harlem Renaissance

The first major public recognition of African-American culture occurred during the Harlem Renaissance pioneered by

The first major public recognition of African-American culture occurred during the Harlem Renaissance pioneered by Alain Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke (September 13, 1885 – June 9, 1954) was an American writer, philosopher, educator, and patron of the arts. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect ...

. In the 1920s and 1930s, African-American music, literature, and art gained wide notice. Authors such as Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen

Nellallitea "Nella" Larsen (born Nellie Walker; April 13, 1891 – March 30, 1964) was an American novelist. Working as a nurse and a librarian, she published two novels, ''Quicksand'' (1928) and '' Passing'' (1929), and a few short stories. Tho ...

and poets such as Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen (born Countee LeRoy Porter; May 30, 1903 – January 9, 1946) was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

Early life

Childhood

Countee LeRoy Porter ...

wrote works describing the African-American experience. Jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

, swing, blues and other musical forms entered American popular music

Popular music is music with wide appeal that is typically distributed to large audiences through the music industry. These forms and styles can be enjoyed and performed by people with little or no musical training.Popular Music. (2015). ''Fu ...

. African-American artists such as William H. Johnson, Aaron Douglas, and Palmer Hayden created unique works of art featuring African Americans.

The Harlem Renaissance was also a time of increased political involvement for African Americans. Among the notable African-American political movements founded in the early 20th century are the Universal Negro Improvement Association

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-Africa ...

and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

. The Nation of Islam, a notable quasi- Islamic religious movement, also began in the early 1930s.

African-American cultural movement

The Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s followed in the wake of thenon-violent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. The movement promoted racial pride

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

and ethnic cohesion in contrast to the focus on integration of the Civil Rights Movement, and adopted a more militant posture in the face of racism. It also inspired a new renaissance in African-American literary and artistic expression generally referred to as the African-American or " Black Arts Movement".

The works of popular

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the total ...

recording artists such as Nina Simone

Eunice Kathleen Waymon (February 21, 1933 – April 21, 2003), known professionally as Nina Simone (), was an American singer, songwriter, pianist, and civil rights activist. Her music spanned styles including classical, folk, gospel, blu ...

(" Young, Gifted and Black") and The Impressions

The Impressions were an American music group originally formed in 1958. Their repertoire includes gospel, doo-wop, R&B, and soul.

The group was founded as the Roosters by Chattanooga, Tennessee natives Sam Gooden, Richard Brooks and Arthur Bro ...

(" Keep On Pushing"), as well as the poetry, fine arts, and literature of the time, shaped and reflected the growing racial and political consciousness. Among the most prominent writers of the African-American Arts Movement were poet Nikki Giovanni

Yolande Cornelia "Nikki" Giovanni Jr. (born June 7, 1943) is an American poet, writer, commentator, activist, and educator. One of the world's most well-known African-American poets,Jane M. Barstow, Yolanda Williams Page (eds)"Nikki Giovanni" ''E ...

; poet and publisher Don L. Lee, who later became known as Haki Madhubuti; poet and playwright Leroi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka; and Sonia Sanchez

Sonia Sanchez (born Wilsonia Benita Driver; September 9, 1934) is an American poet, writer, and professor. She was a leading figure in the Black Arts Movement and has written over a dozen books of poetry, as well as short stories, critical essays ...

. Other influential writers were Ed Bullins

Edward Artie Bullins (July 2, 1935November 13, 2021), sometimes publishing as Kingsley B. Bass Jr, was an American playwright. He won awards including the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award and several Obie Awards. Bullins was associated with ...

, Dudley Randall

Dudley Randall (January 14, 1914 – August 5, 2000) was an African-American poet and poetry publisher from Detroit, Michigan. He founded a pioneering publishing company called Broadside Press in 1965, which published many leading African-America ...

, Mari Evans

Mari Evans (July 16, 1919 – March 10, 2017) was an African-American poet, writer, and dramatist associated with the Black Arts Movement. Evans received grants and awards including a lifetime achievement award from the Indianapolis Public Libra ...

, June Jordan

June Millicent Jordan (July 9, 1936 – June 14, 2002) was an American poet, essayist, teacher, and activist. In her writing she explored issues of gender, race, immigration, and representation.

Jordan was passionate about using Black English ...

, Larry Neal, and Ahmos Zu-Bolton.

Another major aspect of the African-American Arts Movement was the infusion of the African aesthetic, a return to a collective cultural sensibility

''Cultural sensibility'' refers to how sensibility ("openness to emotional impressions, susceptibility and sensitiveness") relates to an individual's moral, emotional or aesthetic standards or ideas. The term should not be confused with the mor ...

and ethnic pride that was much in evidence during the Harlem Renaissance and in the celebration of ''Négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "Nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, developed mainly by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians of the African ...

'' among the artistic and literary circles in the US, Caribbean, and the African continent nearly four decades earlier: the idea that "black is beautiful

Black is beautiful is a cultural movement that was started in the United States in the 1960s by African Americans. It later spread beyond the United States, most prominently in the writings of the Black Consciousness Movement of Steve Biko in ...

". During this time, there was a resurgence of interest in, and an embrace of, elements of African culture within African-American culture that had been suppressed or devalued to conform to Eurocentric America. Natural hair

The natural hair movement is a movement which aims to encourage women and men of African descent to embrace their natural, afro-textured hair. It originated in the United States during the 1960s, with its most recent iteration occurring in the 200 ...

styles, such as the afro

The afro is a hair type created by natural growth of kinky hair, or specifically styled with chemical curling products by individuals with naturally curly or straight hair.Garland, Phyl"Is The Afro On Its Way Out?" ''Ebony'', February 1973. ...

, and African clothing, such as the dashiki

The dashiki is a colorful garment that covers the top half of the body, worn mostly in West Africa. It is also known as a Kitenge in East Africa and is a common item of clothing in Tanzania and Kenya. It has formal and informal versions and var ...

, gained popularity. More importantly, the African-American aesthetic encouraged personal pride and political awareness among African Americans.

Music

African-American music is rooted in the typicallypolyrhythmic

Polyrhythm is the simultaneous use of two or more rhythms that are not readily perceived as deriving from one another, or as simple manifestations of the same meter. The rhythmic layers may be the basis of an entire piece of music (cross-rhyth ...

music of the ethnic groups of Africa, specifically those in the Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

, Sahelean, and Central and Southern regions. African oral traditions, nurtured in slavery, encouraged the use of music to pass on history, teach lessons, ease suffering, and relay messages. The Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n pedigree of African-American music is evident in some common elements: call and response

Call and response is a form of interaction between a speaker and an audience in which the speaker's statements ("calls") are punctuated by responses from the listeners. This form is also used in music, where it falls under the general category of ...

, syncopation, percussion, improvisation, swung notes, blue note

In jazz and blues, a blue note is a note that—for expressive purposes—is sung or played at a slightly different pitch from standard. Typically the alteration is between a quartertone and a semitone, but this varies depending on the musical c ...

s, the use of falsetto, melisma

Melisma ( grc-gre, μέλισμα, , ; from grc, , melos, song, melody, label=none, plural: ''melismata'') is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in this style is refer ...

, and complex multi-part harmony. During slavery, Africans in America blended traditional European hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hy ...

s with African elements to create spirituals

Spirituals (also known as Negro spirituals, African American spirituals, Black spirituals, or spiritual music) is a genre of Christian music that is associated with Black Americans, which merged sub-Saharan African cultural heritage with the ex ...

. The banjo was the first African derived instrument to be played and built in the United States. Slaveholders discovered African-American slaves used drums to communicate.

Many African Americans sing "Lift Every Voice and Sing

"Lift Every Voice and Sing" is a hymn with lyrics by James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) and set to music by his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954). Written from the context of African Americans in the late 19th century, the hymn is a pray ...

" in addition to the American national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and Europea ...

, "The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the b ...

", or in lieu of it. Written by James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871June 26, 1938) was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peop ...

and John Rosamond Johnson in 1900 to be performed for the birthday of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, the song was, and continues to be, a popular way for African Americans to recall past struggles and express ethnic solidarity, faith, and hope for the future. The song was adopted as the "Negro National Anthem" by the NAACP in 1919. Many African-American children are taught the song at school, church or by their families. "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing" traditionally is sung immediately following, or instead of, "The Star-Spangled Banner" at events hosted by African-American churches, schools, and other organizations.

In the 19th century, as the result of the blackface minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of racist theatrical entertainment developed in the early 19th century.

Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people spec ...

, African-American music entered mainstream American society. By the early 20th century, several musical forms with origins in the African-American community had transformed American popular music. Aided by the technological innovations of radio and phonograph records, ragtime

Ragtime, also spelled rag-time or rag time, is a musical style that flourished from the 1890s to 1910s. Its cardinal trait is its syncopated or "ragged" rhythm. Ragtime was popularized during the early 20th century by composers such as Scott J ...

, jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

, blues, and swing also became popular overseas, and the 1920s became known as the Jazz Age. The early 20th century also saw the creation of the first African-American Broadway show

Broadway theatre,Although ''theater'' is generally the spelling for this common noun in the United States (see American and British English spelling differences), 130 of the 144 extant and extinct Broadway venues use (used) the spelling ''Th ...

s, films such as King Vidor

King Wallis Vidor (; February 8, 1894 – November 1, 1982) was an American film director, film producer, and screenwriter whose 67-year film-making career successfully spanned the silent and sound eras. His works are distinguished by a vivid, ...

's ''Hallelujah!'', and operas such as George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned popular, jazz and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions ' ...

's ''Porgy and Bess

''Porgy and Bess'' () is an English-language opera by American composer George Gershwin, with a libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It was adapted from Dorothy Heyward and DuBose Heyward's play '' Porgy'', it ...

''.

Rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm a ...

, doo wop, soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

, and R&B developed in the mid-20th century. These genres became very popular in white audiences and were influences for other genres such as surf. During the 1970s, the dozens

The Dozens is a game played between two contestants in which the participants insult each other until one of them gives up. Common in African-American communities, the Dozens is almost exclusively played in front of an audience, who encourage the ...

, an urban African-American tradition of using rhyming slang to put down one's enemies (or friends), and the West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). For more than 100 years the words ''West Indian'' specifically described natives of the West Indies, but by 1661 Europeans had begun to use it ...

tradition of toasting developed into a new form of music. In the South Bronx the half speaking, half singing rhythmic street talk of "rapping" grew into the hugely successful cultural force known as hip hop.

Contemporary

Hip hop and contemporary R&B would become a multicultural movement, however, it still remained important to many African Americans. The African-American Cultural Movement of the 1960s and 1970s also fueled the growth of funk and later hip hop forms such as

Hip hop and contemporary R&B would become a multicultural movement, however, it still remained important to many African Americans. The African-American Cultural Movement of the 1960s and 1970s also fueled the growth of funk and later hip hop forms such as rap

Rapping (also rhyming, spitting, emceeing or MCing) is a musical form of vocal delivery that incorporates "rhyme, rhythmic speech, and street vernacular". It is performed or chanted, usually over a backing beat or musical accompaniment. The ...

, hip house

Hip house, also known as rap house or house rap, is a musical genre that mixes elements of house music and hip hop, that originated in both London, United Kingdom and Chicago, United States in the mid to late 1980s.

British group the Beatmaster ...

, new jack swing, and go-go

Go-go is a subgenre of funk music with an emphasis on specific rhythmic patterns, and live audience call and response.

Go-go was originated by African-American musicians in the Washington, D.C. area during the mid-60s to late-70s. Go-go has l ...

. House music was created in black communities in Chicago in the 1980s. African-American music has experienced far more widespread acceptance in American popular music in the 21st century than ever before. In addition to continuing to develop newer musical forms, modern artists have also started a rebirth of older genres in the form of genres such as neo soul

Neo soul (sometimes called progressive soul) is a genre of popular music. As a term, it was coined by music industry entrepreneur Kedar Massenburg during the late 1990s to market and describe a style of music that emerged from soul and contempo ...

and modern funk-inspired groups.

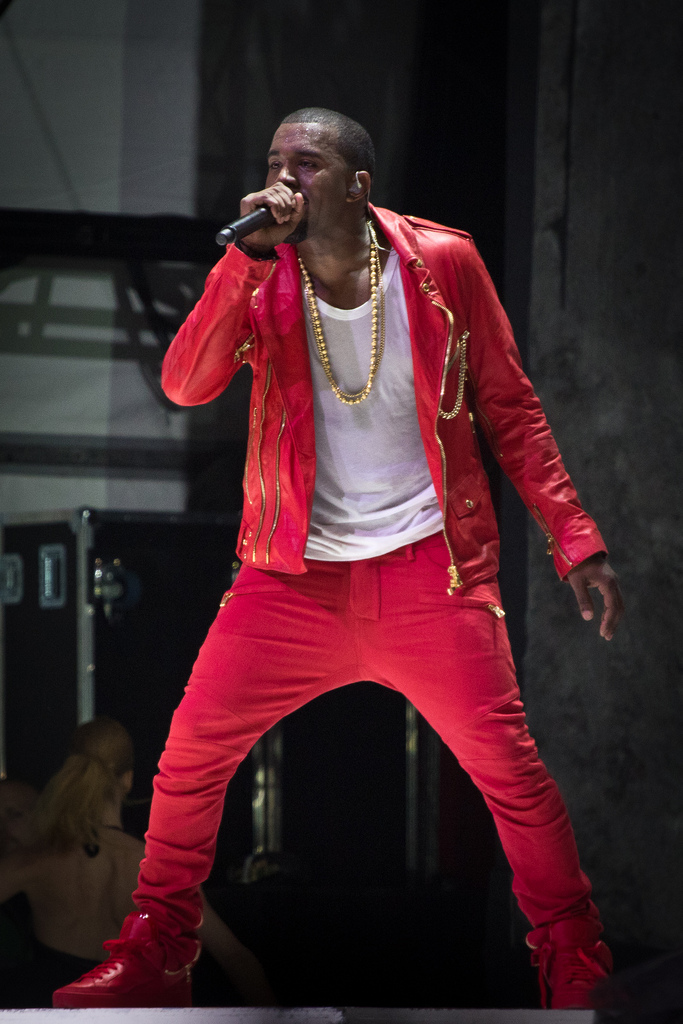

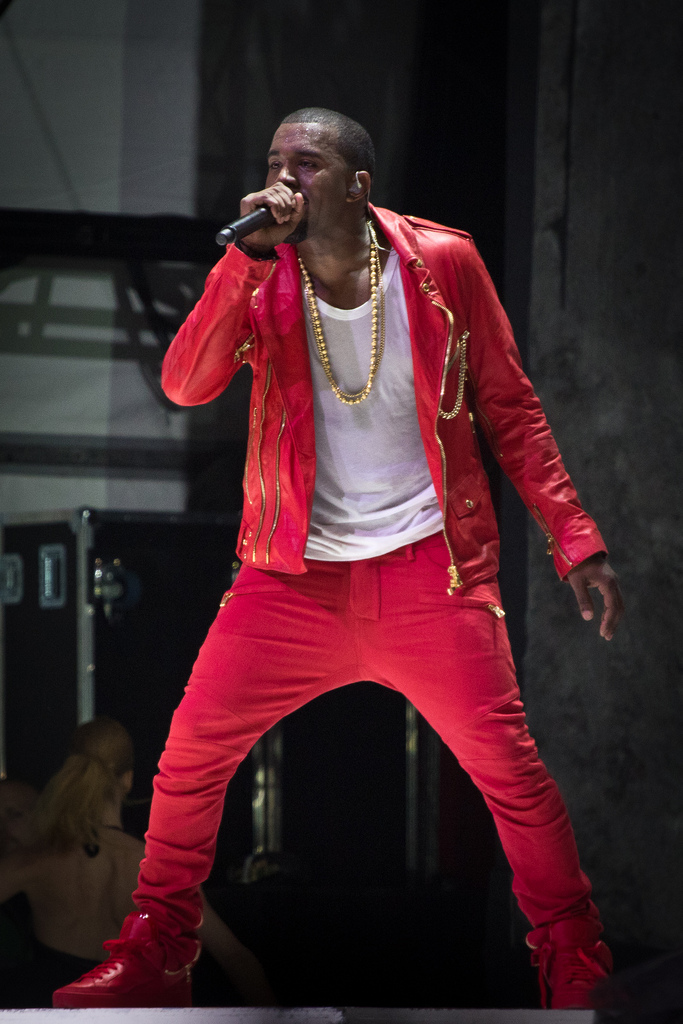

Famous contemporary African American musicians include 50 Cent, Jay-Z, Alicia Keys

Alicia Augello Cook (born January 25, 1981), known professionally as Alicia Keys, is an American singer, songwriter, and pianist. A classically trained pianist, Keys started composing songs when she was 12 and was signed at 15 years old by Col ...

, Usher, Mary J. Blige

Mary Jane Blige ( ; born January 11, 1971) is an American singer, songwriter, and actress. Often referred to as the " Queen of Hip-Hop Soul" and " Queen of R&B", Blige has won nine Grammy Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, four American Music Award ...

, Ne-Yo

Shaffer Chimere Smith (born October 18, 1979), known professionally as Ne-Yo, is an American singer, songwriter, actor, dancer, and record producer. He gained fame for his songwriting abilities when he penned Mario's 2004 hit " Let Me Love You ...

, Snoop Dogg and Kanye West

Ye ( ; born Kanye Omari West ; June 8, 1977) is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, record producer, and fashion designer.

Born in Atlanta and raised in Chicago, West gained recognition as a producer for Roc-A-Fella Records in the ea ...

.

The arts

Dance

African-American dance, like other aspects of African-American culture, finds its earliest roots in the dances of the hundreds of African ethnic groups that made up the enslaved African population in the Americas as well as in traditional folk dances from Europe. Dance in the African tradition, and thus in the tradition of slaves, was a part of both everyday life and special occasions. Many of these traditions such as get down,

African-American dance, like other aspects of African-American culture, finds its earliest roots in the dances of the hundreds of African ethnic groups that made up the enslaved African population in the Americas as well as in traditional folk dances from Europe. Dance in the African tradition, and thus in the tradition of slaves, was a part of both everyday life and special occasions. Many of these traditions such as get down, ring shout

A shout or ring shout is an ecstatic, transcendent religious ritual, first practiced by African slaves in the West Indies and the United States, in which worshipers move in a circle while shuffling and stomping their feet and clapping their hands. ...

s, Akan Line Dancing and other elements of African body language survive as elements of modern dance.

In the 19th century, African-American dance began to appear in minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of racist theatrical entertainment developed in the early 19th century.

Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people spec ...

s. These shows often presented African Americans as caricatures

A caricature is a rendered image showing the features of its subject in a simplified or exaggerated way through sketching, pencil strokes, or other artistic drawings (compare to: cartoon). Caricatures can be either insulting or complimentary, a ...

for ridicule to large audiences. The first African-American dance to become popular with white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

dancers was the cakewalk

The cakewalk was a dance developed from the "prize walks" (dance contests with a cake awarded as the prize) held in the mid-19th century, generally at get-togethers on Black slave plantations before and after emancipation in the Southern Uni ...

in 1891. Later dances to follow in this tradition include the Charleston, the Lindy Hop

The Lindy Hop is an American dance which was born in the Black communities of Harlem, New York City, in 1928 and has evolved since then. It was very popular during the swing era of the late 1930s and early 1940s. Lindy is a fusion of many danc ...

, the Jitterbug

Jitterbug is a generalized term used to describe swing dancing. It is often synonymous with the lindy hop dance but might include elements of the jive, east coast swing, collegiate shag, charleston, balboa and other swing dances.

Swing danc ...

and the swing.''Ballroom, Boogie, Shimmy Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader''. Julie Malnig. Edition: illustrated. University of Illinois Press. 2009, pp. 19–23.

During the Harlem Renaissance, African-American Broadway show

Broadway theatre,Although ''theater'' is generally the spelling for this common noun in the United States (see American and British English spelling differences), 130 of the 144 extant and extinct Broadway venues use (used) the spelling ''Th ...

s such as '' Shuffle Along'' helped to establish and legitimize African-American dancers. African-American dance forms such as tap, a combination of African and European influences, gained widespread popularity thanks to dancers such as Bill Robinson

Bill Robinson, nicknamed Bojangles (born Luther Robinson; May 25, 1878 – November 25, 1949), was an American tap dancer, actor, and singer, the best known and the most highly paid African-American entertainer in the United States during the f ...

and were used by leading white choreographers, who often hired African-American dancers.

Contemporary African-American dance is descended from these earlier forms and also draws influence from African and Caribbean dance forms. Groups such as the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) is a modern dance company based in New York City. It was founded in 1958 by choreographer and dancer Alvin Ailey. It is made up of 32 dancers, led by artistic director Robert Battle and associate ...

have continued to contribute to the growth of this form. Modern popular dance in America is also greatly influenced by African-American dance. American popular dance has also drawn many influences from African-American dance most notably in the hip-hop genre.

One of the uniquely African-American forms of dancing, turfing

Turfing (or turf dancing) is a form of street dance that originated in Oakland, California, characterized by rhythmic movement combined with waving, floor moves, gliding, flexing and cortortioning. It was developed by youth from West Oakland an ...

, emerged from social and political movements in the East Bay in the San Francisco Bay Area. Turfing is a hood dance and a response to the loss of African-American lives, police brutality, and race relations in Oakland, California. The dance is an expression of Blackness, and one that integrates concepts of solidarity, social support, peace, and the discourse of the state of black people in our current social structures.

Twerking

Twerking (; possibly from 'to work') is a type of dance that came out of the bounce music scene of New Orleans in the late 1980s. Individually performed chiefly but not exclusively by women, performers dance to popular music in a sexually prov ...

is an African-American dance similar to dances from Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

in Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

, Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

and the Congo.

Art

From its early origins in slave communities, through the end of the 20th century, African-American art has made a vital contribution to the art of the United States. During the period between the 17th century and the early 19th century, art took the form of small drums, quilts, wrought-iron figures, and ceramic vessels in the southern United States. These artifacts have similarities with comparable crafts in West and Central Africa. In contrast, African-American artisans like the New England–based engraver Scipio Moorhead and the Baltimore portrait painter Joshua Johnson created art that was conceived in a thoroughly western European fashion.

During the 19th century, Harriet Powers made quilts in rural Georgia, United States that are now considered among the finest examples of 19th-century Southern quilting. Later in the 20th century, the women of Gee's Bend developed a distinctive, bold, and sophisticated quilting style based on traditional African-American quilts with a geometric simplicity that developed separately but was like that of Amish quilts and modern art.

After the

From its early origins in slave communities, through the end of the 20th century, African-American art has made a vital contribution to the art of the United States. During the period between the 17th century and the early 19th century, art took the form of small drums, quilts, wrought-iron figures, and ceramic vessels in the southern United States. These artifacts have similarities with comparable crafts in West and Central Africa. In contrast, African-American artisans like the New England–based engraver Scipio Moorhead and the Baltimore portrait painter Joshua Johnson created art that was conceived in a thoroughly western European fashion.

During the 19th century, Harriet Powers made quilts in rural Georgia, United States that are now considered among the finest examples of 19th-century Southern quilting. Later in the 20th century, the women of Gee's Bend developed a distinctive, bold, and sophisticated quilting style based on traditional African-American quilts with a geometric simplicity that developed separately but was like that of Amish quilts and modern art.

After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, museums and galleries began more frequently to display the work of African-American artists. Cultural expression in mainstream venues was still limited by the dominant European aesthetic and by racial prejudice

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

. To increase the visibility of their work, many African-American artists traveled to Europe where they had greater freedom. It was not until the Harlem Renaissance that more European Americans

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent E ...

began to pay attention to African-American art

African-American art is a broad term describing visual art created by African Americans — Americans who also identify as Black. The range of art they have created, and are continuing to create, over more than two centuries is as varied as the ...

in America.

During the 1920s, artists such as Raymond Barthé, Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, and photographer James Van Der Zee became well known for their work. During the Great Depression, new opportunities arose for these and other African-American artists under the WPA

WPA may refer to:

Computing

*Wi-Fi Protected Access, a wireless encryption standard

*Windows Product Activation, in Microsoft software licensing

* Wireless Public Alerting (Alert Ready), emergency alerts over LTE in Canada

* Windows Performance An ...

. In later years, other programs and institutions, such as the New York City-based Harmon Foundation

The Harmon Foundation was established in 1921 by wealthy real-estate developer and philanthropist William E. Harmon (1862–1928). A native of the Midwest, Harmon's father was an officer in the 10th Cavalry Regiment.

The Foundation originally s ...

, helped to foster African-American artistic talent. Augusta Savage, Elizabeth Catlett

Elizabeth Catlett, born as Alice Elizabeth Catlett, also known as Elizabeth Catlett Mora (April 15, 1915 – April 2, 2012) was an African American sculptor and graphic artist best known for her depictions of the Black-American experience in the ...

, Lois Mailou Jones

Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998) was an artist and educator. Her work can be found in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum o ...

, Romare Bearden

Romare Bearden (September 2, 1911 – March 12, 1988) was an American artist, author, and songwriter. He worked with many types of media including cartoons, oils, and collages. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, Bearden grew up in New York City a ...

, Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Armstead Lawrence (September 7, 1917 – June 9, 2000) was an American painter known for his portrayal of African-American historical subjects and contemporary life. Lawrence referred to his style as "dynamic cubism", although by his own ...

, and others exhibited in museums and juried art shows, and built reputations and followings for themselves.

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were very few widely accepted African-American artists. Despite this, The Highwaymen, a loose association of 27 African-American artists from Ft. Pierce, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, created idyllic, quickly realized images of the Florida landscape and peddled some 50,000 of them from the trunks of their cars. They sold their art directly to the public rather than through galleries and art agents, thus receiving the name "The Highwaymen". Rediscovered in the mid-1990s, today they are recognized as an important part of American folk history. Their artwork is widely collected by enthusiasts and original pieces can easily fetch thousands of dollars in auctions and sales.

The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s was another period of resurgent interest in African-American art. During this period, several African-American artists gained national prominence, among them Lou Stovall, Ed Love, Charles White, and Jeff Donaldson. Donaldson and a group of African-American artists formed the Afrocentric collective AfriCOBRA, which remains in existence today. The sculptor Martin Puryear, whose work has been acclaimed for years, was being honored with a 30-year retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in November 2007. Notable contemporary African-American artists include Willie Cole, David Hammons

David Hammons (born July 24, 1943) is an American artist, best known for his works in and around New York City and Los Angeles during the 1970s and 1980s.

Early life

David Hammons was born in 1943 in Springfield, Illinois, the youngest of ten ...

, Eugene J. Martin, Mose Tolliver, Reynold Ruffins, the late William Tolliver, and Kara Walker

Kara Elizabeth Walker (born November 26, 1969) is an American contemporary painter, silhouettist, print-maker, installation artist, filmmaker, and professor who explores race, gender, sexuality, violence, and identity in her work. She is best ...

.

Ceramics

In Charleston,South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, thirteen colonoware from the 18th century were found with folded strip roulette decorations. From the time of colonial America until the 19th century in the United States The 19th century in the United States refers to the period in the United States from 1801 through 1900 in the Gregorian calendar. For information on this period, see:

* History of the United States series:

** History of the United States (1789� ...

, African-Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of enslav ...

and their enslaved African ancestors, as well as Native Americans who were enslaved and not enslaved, were creating colonoware of this pottery style. Roulette decorated pottery likely originated in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

and in the northern region of Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

amid 2000 BCE. The longstanding pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

tradition, from which for the Charleston colonoware derives, likely began its initial development between 800 BCE and 400 BCE in Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mal ...

; thereafter, the pottery tradition expanded around 900 CE into the Lake Chad basin

The Chad Basin is the largest endorheic basin in Africa, centered on Lake Chad. It has no outlet to the sea and contains large areas of semi-arid desert and savanna. The drainage basin is roughly coterminous with the sedimentary basin of the same ...

, into the southeastern region of Mauritania by 1200 CE, and, by the 19th century CE, expanded southward. More specifically, the pottery style for the Charleston colonoware may have been created by 18th century peoples (e.g., Kanuri people

The Kanuri people (Kanouri, Kanowri, also Yerwa, Baribari and several subgroup names) are an African ethnic group living largely in the lands of the former Kanem and Bornu Empires in Niger, Nigeria, Sudan, Libya and Cameroon. Those generally ...

, Hausa people

The Hausa (Endonym, autonyms for singular: Bahaushe (male, m), Bahaushiya (female, f); plural: Hausawa and general: Hausa; exonyms: Ausa; Ajami script, Ajami: ) are the largest native ethnic group in Africa. They speak the Hausa language, which ...

in Kano

Kano may refer to:

Places

*Kano State, a state in Northern Nigeria

* Kano (city), a city in Nigeria, and the capital of Kano State

**Kingdom of Kano, a Hausa kingdom between the 10th and 14th centuries

**Sultanate of Kano, a Hausa kingdom between ...

) of the Kanem–Bornu Empire. Within a broader context, following the 17th century enslavement of western Africans for the farming of rice in South Carolina, the Charleston colonoware may be understood as Africanisms

Africanisms refers to characteristics of African culture that can be traced through societal practices and institutions of the African diaspora. Throughout history, the dispersed descendants of Africans have retained many forms of their ancestr ...

from West/Central Africa, which endured the Middle Passage, and became transplanted into the local culture of colonial-era Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

, South Carolina.

Symbolisms from Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

may have served as identity markers for enslaved African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

creators of stoneware

Stoneware is a rather broad term for pottery or other ceramics fired at a relatively high temperature. A modern technical definition is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic made primarily from stoneware clay or non-refractory fire clay. Whether vi ...

. For example, David Drake’s signature marks (e.g., an "X", a slash) and well as Landrum crosses, which were developed by enslaved African-Americans and appear similar to Kongo cosmograms, are such examples from Edgefield County, South Carolina.

Literature

African-American literature has its roots in the oral traditions of African slaves in America. The slaves used stories andfable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse (poetry), verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphized, and that illustrat ...

s in much the same way as they used music. These stories influenced the earliest African-American writers and poets in the 18th century such as Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley Peters, also spelled Phyllis and Wheatly ( – December 5, 1784) was an American author who is considered the first African-American author of a published book of poetry. Gates, Henry Louis, ''Trials of Phillis Wheatley: Ameri ...

and Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist from, according to his memoir, the Eboe (Igbo) region of the Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria). Enslaved a ...

. These authors reached early high points by telling slave narratives

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

.

During the early 20th century Harlem Renaissance, numerous authors and poets, such as Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Booker T. Washington, grappled with how to respond to discrimination in America. Authors during the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Gwendolyn Brooks wrote about issues of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

, oppression, and other aspects of African-American life. This tradition continues today with authors who have been accepted as an integral part of American literature, with works such as '' Roots: The Saga of an American Family'' by Alex Haley, ''The Color Purple

''The Color Purple'' is a 1982 epistolary novel by American author Alice Walker which won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award for Fiction.

'' by Alice Walker

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and social activist. In 1982, she became the first African-American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, which she was awa ...

, '' Beloved'' by Nobel Prize-winning Toni Morrison

Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford; February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019), known as Toni Morrison, was an American novelist. Her first novel, ''The Bluest Eye'', was published in 1970. The critically acclaimed '' So ...

, and fiction works by Octavia Butler

Octavia Estelle Butler (June 22, 1947 – February 24, 2006) was an American science fiction author and a multiple recipient of the Hugo and Nebula awards. In 1995, Butler became the first science-fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship ...

and Walter Mosley

Walter Ellis Mosley (born January 12, 1952) is an American novelist, most widely recognized for his crime fiction. He has written a series of best-selling historical mysteries featuring the hard-boiled detective Easy Rawlins, a black private inv ...

. Such works have achieved both best-selling and/or award-winning status.

Cinema

African-American films typically feature an African-American cast and are targeted at an African-American audience. More recently, Black films feature multicultural casts, and are aimed at multicultural audiences, even if American Blackness is essential to the storyline.Museums

The African-American Museum Movement emerged during the 1950s and 1960s to preserve the heritage of the African-American experience and to ensure its proper interpretation in American history. Museums devoted to

The African-American Museum Movement emerged during the 1950s and 1960s to preserve the heritage of the African-American experience and to ensure its proper interpretation in American history. Museums devoted to African-American history

African-American history began with the arrival of Africans to North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. Former Spanish slaves who had been freed by Francis Drake arrived aboard the Golden Hind at New Albion in California in 1579. The ...

are found in many African-American neighborhoods. Institutions such as the African American Museum and Library at Oakland, The African American Museum in Cleveland and the Natchez Museum of African American History and Culture were created by African Americans to teach and investigate cultural history that, until recent decades, was primarily preserved through oral traditions.

Other prominent African-American museums include Chicago's DuSable Museum of African American History

The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center, formerly the DuSable Museum of African American History, is a museum in Chicago that is dedicated to the study and conservation of African-American history, culture, and art. It was founded i ...

, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is a Smithsonian Institution museum located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was established in December 2003 and opened its permanent home in ...

, established in 2003 as part of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

in Washington, D.C.

Language

Generations of hardships created by the compounded institutions of slavery imposed on the African-American community which prevented them from learning to read, write English or be educated created distinctive language patterns. Slave owners often intentionally mixed people who spoke different African languages to discourage communication in any language other than English. This, combined with prohibitions against education, led to the development of pidgins, simplified mixtures of two or more languages that speakers of different languages could use to communicate. Examples of pidgins that became fully developed languages include Creole, common toLouisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and Gullah

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

, common to the Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States. Numbering over 100, they are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of South Caroli ...

off the coast of South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to: