A W Pugin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival style of architecture. His work culminated in designing the interior of the

Pugin was the son of the French draughtsman

Pugin was the son of the French draughtsman

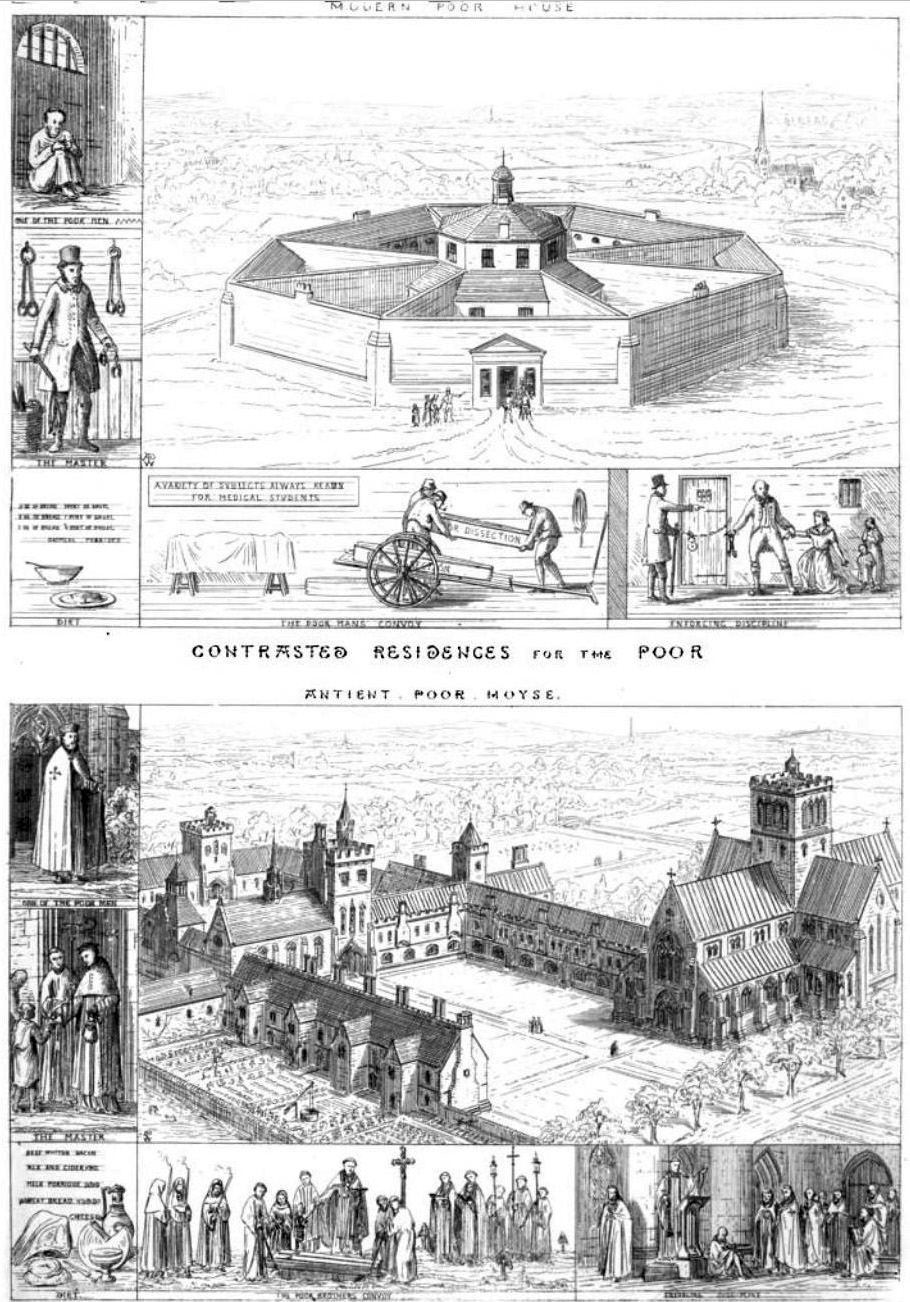

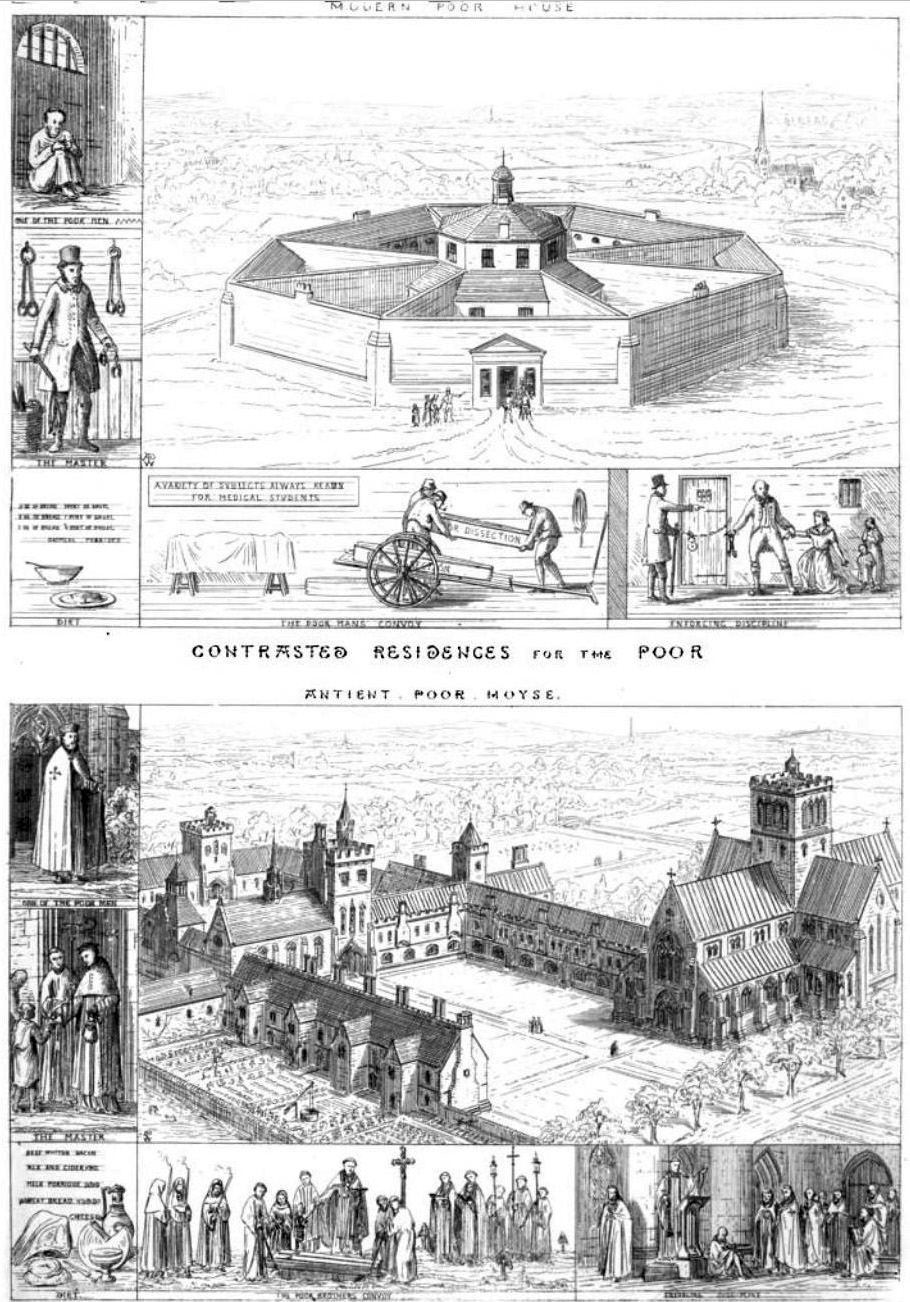

In 1836, Pugin published ''Contrasts'', a polemical book which argued for the revival of the medieval Gothic style, and also "a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages". The book was prompted by the passage of the Church Building Acts of 1818 and 1824, the former of which is often called the Million Pound Act due to the appropriation amount by Parliament for the construction of new Anglican churches in Britain. The new churches constructed from these funds, many of them in a Gothic-Revival style due to the assertion that it was the "cheapest" style to use, were often criticised by Pugin and many others for their shoddy design and workmanship and poor liturgical standards relative to an authentic Gothic structure.

Each plate in ''Contrasts'' selected a type of urban building and contrasted the 1830 example with its 15th-century equivalent. In one example, Pugin contrasted a medieval monastic foundation, where monks fed and clothed the needy, grew food in the gardens – and gave the dead a decent burial – with "a

In 1836, Pugin published ''Contrasts'', a polemical book which argued for the revival of the medieval Gothic style, and also "a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages". The book was prompted by the passage of the Church Building Acts of 1818 and 1824, the former of which is often called the Million Pound Act due to the appropriation amount by Parliament for the construction of new Anglican churches in Britain. The new churches constructed from these funds, many of them in a Gothic-Revival style due to the assertion that it was the "cheapest" style to use, were often criticised by Pugin and many others for their shoddy design and workmanship and poor liturgical standards relative to an authentic Gothic structure.

Each plate in ''Contrasts'' selected a type of urban building and contrasted the 1830 example with its 15th-century equivalent. In one example, Pugin contrasted a medieval monastic foundation, where monks fed and clothed the needy, grew food in the gardens – and gave the dead a decent burial – with "a

Pugin was a prolific designer of stained glass. He worked with

Pugin was a prolific designer of stained glass. He worked with

In February 1852, while travelling with his son Edward by train, Pugin had a total breakdown and arrived in London unable to recognise anyone or speak coherently. For four months he was confined to a private asylum, Kensington House. In June, he was transferred to the

In February 1852, while travelling with his son Edward by train, Pugin had a total breakdown and arrived in London unable to recognise anyone or speak coherently. For four months he was confined to a private asylum, Kensington House. In June, he was transferred to the  On Pugin's death certificate, the cause listed was "convulsions followed by coma". Pugin's biographer, Rosemary Hill, suggests that, in the last year of his life, he had had

On Pugin's death certificate, the cause listed was "convulsions followed by coma". Pugin's biographer, Rosemary Hill, suggests that, in the last year of his life, he had had

In October 1834, the

In October 1834, the

The first

The first

* Hall of John Halle,

* Hall of John Halle,

– extant

*Church of Assumption of Mary,

*Church of Assumption of Mary,

The Pugin SocietyAugustus Welby Northmore Pugin 1812–1852, A comprehensive overview of Pugin's life with nearly 400 imagesThe Pugin Foundation – Australian Works of Augustus Welby Northmore PuginAugustus Pugin's Map Room - UK Parliament Living HeritageSt Giles' Roman Catholic Church

Cheadle, Staffordshire with 360° images of the interior

Papers of AWN Pugin

at the UK Parliamentary Archives

"Pugin's manifesto"

an essay on Pugin's early work fro

TLS

1 August 2007.

A Victorian Novel in Stone: the Houses of Parliament tell the story of Britain's past and its peculiar constitution

''The Wall Street Journal'', 21 March 2009

Pugin: God's Own Architect

BBC4, 19 January 2012 * *

Floriated Ornament: A Series of Thirty-One Designs

Pugin, Augustus W. N. London: H.G. Bohn, 1849

NA997 P8.8o

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Library

Table designed by A.W.N. Pugin for Windsor Castle, 1828.

Butchoff Antiques, London. * A. W. N. Pugin Drawings. James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Parliamentary Archives, Papers of AWN Pugin, (1812-1852); Architect

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pugin, Augustus Welby Northmore 1812 births 1852 deaths 19th-century English architects Architects of cathedrals Architects of Roman Catholic churches British stained glass artists and manufacturers English furniture designers Converts to Roman Catholicism English ecclesiastical architects English people of French descent English Roman Catholics Gothic Revival architects People educated at Christ's Hospital People with mental disorders

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England, and its iconic clock tower, later renamed the Elizabeth Tower, which houses the bell known as Big Ben

Big Ben is the nickname for the Great Bell of the Great Clock of Westminster, at the north end of the Palace of Westminster in London, England, and the name is frequently extended to refer also to the clock and the clock tower. The officia ...

. Pugin designed many churches in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, and some in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. He was the son of Auguste Pugin

Augustus Charles Pugin (born Auguste-Charles Pugin; 1762 – 19 December 1832) was an Anglo-French artist, architectural Drafter, draughtsman, and writer on medieval architecture. He was born in Paris, then the Kingdom of France, but his fathe ...

, and the father of Edward Welby Pugin and Peter Paul Pugin, who continued his architectural firm as Pugin & Pugin

Pugin & Pugin (fl. 1851– c. 1958) was a London-based family firm of church architects, founded in the Westminster office of Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852). The firm was succeeded by his sons Cuthbert Welby Pugin (1840–1928) an ...

. He also created Alton Castle

Alton Castle is a Gothic-revival castle, on a hill above the Churnet Valley, in the village of Alton, Staffordshire, England. The site has been fortified in wood since Saxon times, with a stone castle dating from the 12th century. The current ...

in Alton, Staffordshire.

Biography

Pugin was the son of the French draughtsman

Pugin was the son of the French draughtsman Auguste Pugin

Augustus Charles Pugin (born Auguste-Charles Pugin; 1762 – 19 December 1832) was an Anglo-French artist, architectural Drafter, draughtsman, and writer on medieval architecture. He was born in Paris, then the Kingdom of France, but his fathe ...

, who had immigrated to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

as a result of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and had married Catherine Welby of the Welby family of Denton, Lincolnshire, England. Pugin was born on 1 March 1812 at his parents' house in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest ...

, London, England. Between 1821 and 1838, Pugin's father published a series of volumes of architectural drawings, the first two entitled ''Specimens of Gothic Architecture'' and the following three ''Examples of Gothic Architecture'', that not only remained in print but were the standard references for Gothic architecture for at least the next century.

Religion

As a child, his mother took Pugin each Sunday to the services of the fashionable Scottish Presbyterian preacherEdward Irving

Edward Irving (4 August 17927 December 1834) was a Scottish clergyman, generally regarded as the main figure behind the foundation of the Catholic Apostolic Church.

Early life

Edward Irving was born at Annan, Annandale the second son of Ga ...

(later the founder of the Holy Catholic Apostolic Church

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in Scotland around 1831 and later spread to Germany and the United States.Hatton Garden

Hatton Garden is a street and commercial zone in the Holborn district of the London Borough of Camden, abutting the narrow precinct of Saffron Hill which then abuts the City of London. It takes its name from Sir Christopher Hatton, a favouri ...

, Camden, London. Pugin quickly rebelled against this version of Christianity: according to Benjamin Ferrey

Benjamin Ferrey FSA FRIBA (1 April 1810–22 August 1880) was an English architect who worked mostly in the Gothic Revival.

Family

Benjamin Ferrey was the youngest son of Benjamin Ferrey Snr (1779–1847), a draper who became Mayor of Christc ...

, Pugin "always expressed unmitigated disgust at the cold and sterile forms of the Scottish church; and the moment he broke free from the trammels imposed on him by his mother, he rushed into the arms of a church which, pompous by its ceremonies, was attractive to his imaginative mind".

Education and early ventures

Pugin learned drawing from his father, and for a while attendedChrist's Hospital

Christ's Hospital is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex. The school was founded in 1552 and received its first royal charter in 1553. ...

. After leaving school, he worked in his father's office, and in 1825 and 1827 accompanied him on visits to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. His first commissions independent of his father were for designs for the goldsmiths Rundell and Bridge, and for designs for furniture of Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

from the upholsterers Morel and Seddon. Through a contact made while working at Windsor, he became interested in the design of theatrical scenery, and in 1831 obtained a commission to design the sets for the production of the new opera ''Kenilworth

Kenilworth ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Warwick District in Warwickshire, England, south-west of Coventry, north of Warwick and north-west of London. It lies on Finham Brook, a tributary of the River Sowe, which joins the ...

'' at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. He also developed an interest in sailing, and briefly commanded a small merchant schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

trading between Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former Provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

, which allowed him to import examples of furniture and carving from Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

, with which he later furnished his house at Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside town in the district of Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to the Census, there was a populati ...

in Kent.Eastlake, 1872, p. 148. During one voyage in 1830, he was wrecked on the Scottish coast near Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

, as a result of which he came into contact with Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

architect James Gillespie Graham

James Gillespie Graham (11 June 1776 – 11 March 1855) was a Scottish architect, prominent in the early 19th century.

Life

Graham was born in Dunblane on 11 June 1776. He was the son of Malcolm Gillespie, a solicitor. He was christened as J ...

, who advised him to abandon seafaring for architecture. He then established a business supplying historically accurate carved wood and stone detailing for the increasing number of buildings being constructed in the Gothic Revival style, but the enterprise quickly failed.

Marriages

In 1831, at the age of 19, Pugin married the first of his three wives, Anne Garnet. She died a few months later in childbirth, leaving him a daughter. He had a further six children, including the future architect Edward Welby Pugin, with his second wife, Louisa Burton, who died in 1844. His third wife, Jane Knill, kept a journal of their marital life, from their marriage in 1848 to Pugin's death, which was later published. Their son was the architect Peter Paul Pugin.Salisbury

Following his second marriage in 1833, Pugin moved toSalisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, with his wife, and in 1835 bought of land in Alderbury, about outside the town. On this he built a Gothic Revival style house for his family, which he named St. Marie's Grange. Of it, Charles Eastlake

Charles Locke Eastlake (11 March 1836 – 20 November 1906) was a British architect and furniture designer.

His uncle, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake PRA (born in 1793), was a Keeper of the National Gallery, from 1843 to 1847, and from 1855 its fi ...

said "he had not yet learned the art of combining a picturesque exterior with the ordinary comforts of an English home."

Conversion to the Roman Catholic Church

In 1834, Pugin converted to theRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and was received into it the following year.

British society at the start of the 19th century often discriminated against dissenters from the Church of England, although things began to change during Pugin's lifetime, helping to make Pugin's eventual conversion to Roman Catholicism more socially acceptable. For example, dissenters could not take degrees at the established universities of Oxford and Cambridge until 1871, but the University of London (later renamed University College London) was founded near Pugin's birthplace in 1826 with the express purpose of educating dissenters to degree standard (although it would not be able to confer degrees until 1836). Dissenters were also unable to serve on parish or city councils, be a member of Parliament, serve in the armed forces or on a jury. A number of reforms across the 19th century relieved these restrictions, one of which was the Roman Catholic Relief Act

The Roman Catholic Relief Bills were a series of measures introduced over time in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries before the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom to remove the restrictions and prohibitions impos ...

of 1829, which allowed Roman Catholics to become MPs.

Pugin's conversion acquainted him with new patrons and employers. In 1832 he made the acquaintance of John Talbot, 16th Earl of Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 16th Earl of Shrewsbury, 16th Earl of Waterford (18 March 1791 – 9 November 1852) was a British peer and aristocrat. Sometimes known as "Good Earl John", he has been described as "the most prominent British Catholic of his day ...

, a Catholic sympathetic to his aesthetic theory and who employed him in alterations and additions to his residence of Alton Towers

Alton Towers Resort ( ) (often referred to as Alton Towers) is a theme park and resort complex in Staffordshire, England, near the village of Alton. The park is operated by Merlin Entertainments Group and incorporates a theme park, water pa ...

, which subsequently led to many more commissions.Eastlake, 1872, p. 150. Shrewsbury commissioned him to build St. Giles Roman Catholic Church, Cheadle, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands C ...

, which was completed in 1846, and Pugin was also responsible for designing the oldest Catholic Church in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, St Peter and Paul Church, Newport

St. Peter and St. Paul Roman Catholic Church is a parish of the Roman Catholic Church in Newport, Shropshire, England. The parish covers Newport and the surrounding villages as far as Hinstock.

Salters Hall, in Salters Lane, Newport, is attach ...

.

''Contrasts''

In 1836, Pugin published ''Contrasts'', a polemical book which argued for the revival of the medieval Gothic style, and also "a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages". The book was prompted by the passage of the Church Building Acts of 1818 and 1824, the former of which is often called the Million Pound Act due to the appropriation amount by Parliament for the construction of new Anglican churches in Britain. The new churches constructed from these funds, many of them in a Gothic-Revival style due to the assertion that it was the "cheapest" style to use, were often criticised by Pugin and many others for their shoddy design and workmanship and poor liturgical standards relative to an authentic Gothic structure.

Each plate in ''Contrasts'' selected a type of urban building and contrasted the 1830 example with its 15th-century equivalent. In one example, Pugin contrasted a medieval monastic foundation, where monks fed and clothed the needy, grew food in the gardens – and gave the dead a decent burial – with "a

In 1836, Pugin published ''Contrasts'', a polemical book which argued for the revival of the medieval Gothic style, and also "a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages". The book was prompted by the passage of the Church Building Acts of 1818 and 1824, the former of which is often called the Million Pound Act due to the appropriation amount by Parliament for the construction of new Anglican churches in Britain. The new churches constructed from these funds, many of them in a Gothic-Revival style due to the assertion that it was the "cheapest" style to use, were often criticised by Pugin and many others for their shoddy design and workmanship and poor liturgical standards relative to an authentic Gothic structure.

Each plate in ''Contrasts'' selected a type of urban building and contrasted the 1830 example with its 15th-century equivalent. In one example, Pugin contrasted a medieval monastic foundation, where monks fed and clothed the needy, grew food in the gardens – and gave the dead a decent burial – with "a panopticon

The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be o ...

workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

where the poor were beaten, half-starved and sent off after death for dissection. Each structure was the built expression of a particular view of humanity: Christianity versus Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

." Pugin's biographer, Rosemary Hill, wrote: "The drawings were all calculatedly unfair. King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

was shown from an unflatteringly skewed angle, while Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniq ...

, was edited to avoid showing its famous Tom Tower

Tom Tower is a bell tower in Oxford, England, named after its bell, Great Tom. It is over Tom Gate, on St Aldates, the main entrance of Christ Church, Oxford, which leads into Tom Quad. This square tower with an octagonal lantern and facet ...

because that was by Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

and so not medieval. But the cumulative rhetorical force was tremendous."

In 1841 he published his illustrated ''The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture'', which was premised on his two fundamental principles of Christian architecture. He conceived of "Christian architecture" as synonymous with medieval, "Gothic", or "pointed", architecture. In the work, he also wrote that contemporary craftsmen seeking to emulate the style of medieval workmanship should reproduce its methods.

Ramsgate

In 1841 he leftSalisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

,Eastlake, 1872, pp. 150–1. having found it an inconvenient base for his growing architectural practice. He sold St. Marie's Grange at a considerable financial loss, and moved temporarily to Cheyne Walk

Cheyne Walk is an historic road in Chelsea, London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It runs parallel with the River Thames. Before the construction of Chelsea Embankment reduced the width of the Thames here, it fronted ...

in Chelsea, London. He had, however, already purchased a parcel of land at West Cliff, Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside town in the district of Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to the Census, there was a populati ...

, Thanet in Kent, where he proceeded to build for himself a large house and, at his own expense, a church dedicated to St. Augustine, after whom he thought himself named. He worked on this church whenever funds permitted it. His second wife died in 1844 and was buried at St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham

The Metropolitan Cathedral Church and Basilica of Saint Chad is a Catholic cathedral in Birmingham, England. It is the mother church of the Archdiocese of Birmingham and is dedicated to Saint Chad of Mercia.

Designed by Augustus Welby Pugin an ...

, which he had designed.

Architectural commissions

Following the destruction by fire of thePalace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, in 1834, Pugin was employed by Sir Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also respon ...

to supply interior designs for his entry to the architectural competition which would determine who would build the new Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

. Pugin also supplied drawings for the entry of James Gillespie Graham. This followed a period of employment when Pugin had worked with Barry on the interior design of King Edward's School, Birmingham

King Edward's School (KES) is an independent day school for boys in the British public school tradition, located in Edgbaston, Birmingham. Founded by King Edward VI in 1552, it is part of the Foundation of the Schools of King Edward VI in Bir ...

. Despite his conversion to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in 1834, Pugin designed and refurbished both Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

churches throughout England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

.

Other works include St. Chad's Cathedral, Erdington Abbey, and Oscott College

St Mary's College in New Oscott, Birmingham, often called Oscott College, is the Roman Catholic seminary of the Archdiocese of Birmingham in England and one of the three seminaries of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.

Purpose

Oscott C ...

, all in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. He also designed the collegiate buildings of St. Patrick and St. Mary in St. Patrick's College, Maynooth

St Patrick's Pontifical University, Maynooth ( ga, Coláiste Naoimh Phádraig, Maigh Nuad), is the "National Seminary for Ireland" (a Roman Catholic college), and a pontifical university, located in the town of Maynooth, from Dublin, Ireland ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

; though not the collegiate chapel. His original plans included both a chapel and an ''aula maxima'' (great hall), neither of which were built because of financial constraints. The college chapel was designed by a follower of Pugin, the Irish architect J. J. McCarthy. Also in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, Pugin designed St. Mary's Cathedral in Killarney

Killarney ( ; ga, Cill Airne , meaning 'church of sloes') is a town in County Kerry, southwestern Ireland. The town is on the northeastern shore of Lough Leane, part of Killarney National Park, and is home to St Mary's Cathedral, Ross Cast ...

, St. Aidan's Cathedral in Enniscorthy

Enniscorthy () is the second-largest town in County Wexford, Ireland. At the 2016 census, the population of the town and environs was 11,381. The town is located on the picturesque River Slaney and in close proximity to the Blackstairs Mountain ...

(renovated in 1996), and the Dominican Church of the Holy Cross in Tralee

Tralee ( ; ga, Trá Lí, ; formerly , meaning 'strand of the Lee River') is the county town of County Kerry in the south-west of Ireland. The town is on the northern side of the neck of the Dingle Peninsula, and is the largest town in Count ...

. He revised the plans for St. Michael Church in Ballinasloe

Ballinasloe ( ; ) is a town in the easternmost part of County Galway in Connacht. Located at an ancient crossing point on the River Suck, evidence of ancient settlement in the area includes a number of Bronze Age sites. Built around a 12th-ce ...

, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

. Bishop Wareing also invited Pugin to design what eventually became Northampton Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of St Mary and St Thomas is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Northampton, England. It is the seat of the Bishop of Northampton and mother church of the Diocese of Northampton which covers the counties of Northamptonshire, Bed ...

, a project that was completed in 1864 by Pugin's son Edward Welby Pugin.

Pugin visited Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

in 1847; his experience there confirmed his dislike of Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

and Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

architecture, but he found much to admire in the medieval art of northern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

.

Stained Glass

Pugin was a prolific designer of stained glass. He worked with

Pugin was a prolific designer of stained glass. He worked with Thomas Willement

Thomas Willement (18 July 1786 – 10 March 1871) was an English stained glass artist, called "the father of Victorian stained glass", active from 1811 to 1865.

Biography

Willement was born at St Marylebone, London. Like many early 19th centu ...

, William Warrington

William Warrington, (1796–1869), was an English maker of stained glass windows. His firm, operating from 1832 to 1875, was one of the earliest of the English Medieval revival and served clients such as Norwich and Peterborough Cathedrals. ...

and William Wailes before persuading his friend John Hardman to start stained glass production.

Illness and death

In February 1852, while travelling with his son Edward by train, Pugin had a total breakdown and arrived in London unable to recognise anyone or speak coherently. For four months he was confined to a private asylum, Kensington House. In June, he was transferred to the

In February 1852, while travelling with his son Edward by train, Pugin had a total breakdown and arrived in London unable to recognise anyone or speak coherently. For four months he was confined to a private asylum, Kensington House. In June, he was transferred to the Royal Bethlem Hospital

Bethlem Royal Hospital, also known as St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlehem Hospital and Bedlam, is a psychiatric hospital in London. Its famous history has inspired several horror books, films and TV series, most notably '' Bedlam'', a 1946 film with ...

, popularly known as Bedlam.Hill, 2007, pp. 484–490 At that time, Bethlem Hospital was opposite St George's Cathedral, Southwark, one of Pugin's major buildings, where he had married his third wife, Jane, in 1848. Jane and a doctor removed Pugin from Bedlam and took him to a private house in Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London ...

where they attempted therapy, and he recovered sufficiently to recognise his wife. In September, Jane took her husband back to The Grange in Ramsgate, where he died on 14 September 1852. He is buried in his church next to The Grange, St Augustine's, Ramsgate.

On Pugin's death certificate, the cause listed was "convulsions followed by coma". Pugin's biographer, Rosemary Hill, suggests that, in the last year of his life, he had had

On Pugin's death certificate, the cause listed was "convulsions followed by coma". Pugin's biographer, Rosemary Hill, suggests that, in the last year of his life, he had had hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is the condition that occurs due to excessive production of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland. Thyrotoxicosis is the condition that occurs due to excessive thyroid hormone of any cause and therefore includes hyperthyroidis ...

which would account for his symptoms of exaggerated appetite, perspiration, and restlessness. Hill writes that Pugin's medical history, including eye problems and recurrent illness from his early twenties, suggests that he contracted syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

in his late teens, and this may have been the cause of his death at the age of 40.Hill, 2007, pp. 492–494

Palace of Westminster

In October 1834, the

In October 1834, the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

burned down

A conflagration is a large fire. Conflagrations often damage human life, animal life, health, and/or property. A conflagration can begin accidentally, be naturally caused (wildfire), or intentionally created (arson). A very large fire can produc ...

. Subsequently, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

, wanted, now that he was premier, to disassociate himself from the controversial John Wilson Croker

John Wilson Croker (20 December 178010 August 1857) was an Anglo-Irish statesman and author.

Life

He was born in Galway, the only son of John Croker, the surveyor-general of customs and excise in Ireland. He was educated at Trinity College Dubl ...

, who was a founding member of the Athenaeum Club; a close associate of the pre-eminent neoclassical architects James Burton

James Edward Burton (born August 21, 1939, in Dubberly, Louisiana) is an American guitarist. A member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame since 2001 (his induction speech was given by longtime fan Keith Richards), Burton has also been recognized ...

and Decimus Burton

Decimus Burton (30 September 1800 – 14 December 1881) was one of the foremost English architects and landscapers of the 19th century. He was the foremost Victorian architect in the Roman revival, Greek revival, Georgian neoclassical and R ...

; an advocate of neoclassicism; and a repudiator of the neo-gothic style. Consequently, Peel appointed a committee chaired by Edward Cust, a detestor of the style of John Nash and William Wilkins, which resolved that the new Houses of Parliament would have to be in either the 'gothic' or the 'Elizabethan' style. Augustus W. N. Pugin, the foremost expert on the Gothic, had to submit each of his designs through, and thus in the name of, other architects, Gillespie-Graham and Charles Barry, because he had recently openly and fervently converted to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, as a consequence of which any design submitted in his own name would certainly have been automatically rejected; the design he submitted for improvements to Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the ...

, in 1843 were rejected for this reason. The design for Parliament that Pugin submitted through Barry won the competition. Subsequent to the announcement of the design ascribed to Barry, William Richard Hamilton, who had been secretary to Elgin during the acquisition of the marbles, published a pamphlet in which he censured the fact that 'gothic barbarism' had been preferred to the masterful designs of Ancient Greece and Rome: but the judgement was not altered, and was ratified by the Commons and the Lords. The commissioners subsequently appointed Pugin to assist in the construction of the interior of the new Palace, to the design of which Pugin himself had been the foremost determiner. Pugin's biographer, Rosemary Hill

Rosemary Hill (born 10 April 1957) is an English writer and historian.

Life

Hill has published widely on 19th- and 20th-century cultural history, but she is best known for ''God's Architect'' (2007), her biography of Augustus Pugin. The book won ...

, shows that Barry designed the Palace as a whole, and only he could co-ordinate such a large project and deal with its difficult paymasters, but he relied entirely on Pugin for its Gothic interiors, wallpapers and furnishings. The first stone of the new Pugin-Barry design was laid on 27 April 1840.

During the competition for the design of the new Houses of Parliament, Decimus Burton, 'the land's leading classicist', was vituperated with continuous invective, which Guy Williams has described as an 'anti-Burton campaign', by the foremost advocate of the neo-gothic style, Augustus W. N. Pugin, who was made enviously reproachful that Decimus "had done much more than Pugin's father ( Augustus Charles Pugin) to alter the appearance of London". Pugin attempted to popularize advocacy of the neo-gothic, and repudiation of the neoclassical, by composing and illustrating books that contended the supremacy of the former and the degeneracy of the latter, which were published from 1835. In 1845, Pugin, in his ''Contrasts: or a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day'', which the author had to publish himself as a consequence of the extent of the defamation of society architects therein, satirized John Nash as "Mr Wash, Plasterer, who jobs out Day Work on Moderate Terms", and Decimus Burton as "Talent of No Consequence, Premium Required", and included satirical sketches of Nash's Buckingham Palace and Burton's triumphal arch at Hyde Park. Consequently, the amount of commissions received by Decimus declined, although Decimus retained a close friendship with the aristocrats amongst his patrons, who continued to commission him.

At the end of Pugin's life, in February 1852, Barry visited him in Ramsgate and Pugin supplied a detailed design for the iconic Palace clock tower, in 2012 dubbed the Elizabeth Tower but popularly known as Big Ben

Big Ben is the nickname for the Great Bell of the Great Clock of Westminster, at the north end of the Palace of Westminster in London, England, and the name is frequently extended to refer also to the clock and the clock tower. The officia ...

. The design is very close to earlier designs by Pugin, including an unbuilt scheme for Scarisbrick Hall, Lancashire. The tower was Pugin's last design before descending into madness. In her biography, Hill quotes Pugin as writing of what is probably his best-known building: "I never worked so hard in my life sfor Mr Barry for tomorrow I render all the designs for finishing his bell tower & it is beautiful & I am the whole machinery of the clock." Hill writes that Barry omitted to give any credit to Pugin for his huge contribution to the design of the new Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

. In 1867, after the deaths of both Pugin and Barry, Pugin's son Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

published a pamphlet, ''Who Was the Art Architect of the Houses of Parliament, a statement of facts'', in which he asserted that his father was the "true" architect of the building, and not Barry.

Pugin in Ireland

Pugin was invited to Ireland by the Redmond family, initially to work inCounty Wexford

County Wexford ( ga, Contae Loch Garman) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was based on the historic Gaelic territory of Hy Kinsella (''Uí C ...

. He arrived in Ireland in 1838 at a time of greater religious tolerance, when Catholic churches were permitted to be built. Most of his work in Ireland consisted of religious buildings. Pugin demanded the highest quality of workmanship from his craftsmen, particularly the stonemasons. His subsequent visits to the country were brief and infrequent. He was the main architect of St Aidan's Roman Catholic Cathedral for the diocese of Ferns in Enniscorthy, County Wexford. Pugin was the architect of the Russell Library at St. Patrick's College, Maynoooth, although he did not live to see its completion. Pugin did the initial design of St. Mary's Cathedral, Killarney.

Pugin and Australia

The first

The first Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Bishop of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Australia, John Bede Polding

John Bede Polding, OSB (18 November 1794 in 16 March 1877 ) was the first Roman Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Australia.

Early life

Polding was born in Liverpool, England on 18 November 1794. His father was of Dutch descent and his mothe ...

, met Pugin and was present when St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham

The Metropolitan Cathedral Church and Basilica of Saint Chad is a Catholic cathedral in Birmingham, England. It is the mother church of the Archdiocese of Birmingham and is dedicated to Saint Chad of Mercia.

Designed by Augustus Welby Pugin an ...

and St Giles' Catholic Church, Cheadle were officially opened. Although Pugin never visited Australia, Polding persuaded Pugin to design a series of churches for him. Although a number of churches do not survive, St Francis Xavier's in Berrima, New South Wales

Berrima () is a historic village in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia, in Wingecarribee Shire. The village, once a major town, is located on the Old Hume Highway between Sydney and Canberra. It was previously known officiall ...

, is regarded as a fine example of a Pugin church. Polding blessed the foundation stone in February 1849, and the church was completed in 1851.

St Stephen's Chapel, now in the cathedral grounds in Elizabeth Street, Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

, was built to a design of Pugin. Construction began in 1848, and the first Mass in the church was celebrated on 12 May 1850. In 1859 James Quinn was appointed Bishop of Brisbane, Brisbane becoming a diocese, and Pugin's small church became a cathedral. When the new cathedral of St Stephen was opened in 1874 the small Pugin church became a schoolroom, and later church offices and storage room. It was several times threatened with demolition before its restoration in the 1990s. In Sydney, there are several altered examples of his work, namely St Benedict's, Chippendale; St Charles Borromeo, Ryde

Ryde is an English seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight. The built-up area had a population of 23,999 according to the 2011 Census and an estimate of 24,847 in 2019. Its growth as a seaside resort came ...

; the former church of St Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

(next to the existing church), Balmain; and St Patrick's Cathedral, Parramatta

St Patrick's Cathedral, Parramatta is the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Parramatta and the seat and residence of the Catholic Bishop of Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia, currently the Most Reverend Vincent Long Van Nguy ...

, which was gutted by a fire in 1996

According to Steve Meacham writing in the Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily compact newspaper published in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and owned by Nine. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper ...

, Pugin's legacy in Australia is particularly of the idea of what a church should look like:

After his death, Pugin's two sons, E. W. Pugin and Peter Paul Pugin, continued operating their father's architectural firm under the name Pugin & Pugin. Their work includes most of the "Pugin" buildings in Australia and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

.

Reputation and influence

Eastlake, writing in 1872, noted that the quality of construction in Pugin's buildings was often poor, and believed he was lacking in technical knowledge, his strength lying more in his facility as a designer of architectural detail. Pugin's legacy began to fade immediately after his death. This was partly due to the hostility ofJohn Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

. In his appendix to '' The Stones of Venice'' (1851), Ruskin wrote of Pugin, "he is not a great architect but one of the smallest possible or conceivable architects".Hill, 2007, pp. 458–459 Contemporaries and admirers of Pugin, including Sir Henry Cole

Sir Henry Cole FRSA (15 July 1808 – 18 April 1882) was a British civil servant and inventor who facilitated many innovations in commerce and education in the 19th century in the United Kingdom. Cole is credited with devising the concept of ...

, protested at the viciousness of the attack and pointed out that Ruskin's idea on style had much in common with Pugin's. After Pugin's death, Ruskin "outlived and out-talked him by half a century". Sir Kenneth Clark

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television ...

wrote, "If Ruskin had never lived, Pugin would never have been forgotten."Clark, 1962, p. 144

Nonetheless, Pugin's architectural ideas were carried forward by two young architects who admired him and had attended his funeral, W. E. Nesfield and Norman Shaw

Richard Norman Shaw RA (7 May 1831 – 17 November 1912), also known as Norman Shaw, was a British architect who worked from the 1870s to the 1900s, known for his country houses and for commercial buildings. He is considered to be among the g ...

. George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

, William Butterfield

William Butterfield (7 September 1814 – 23 February 1900) was a Gothic Revival architect and associated with the Oxford Movement (or Tractarian Movement). He is noted for his use of polychromy.

Biography

William Butterfield was born in Lon ...

and George Edmund Street

George Edmund Street (20 June 1824 – 18 December 1881), also known as G. E. Street, was an English architect, born at Woodford in Essex. Stylistically, Street was a leading practitioner of the Victorian Gothic Revival. Though mainly an eccle ...

were influenced by Pugin's designs, and continued to work out the implication of ideas he had sketched in his writings. In Street's office, Philip Webb

Philip Speakman Webb (12 January 1831 – 17 April 1915) was a British architect and designer sometimes called the Father of Arts and Crafts Architecture. His use of vernacular architecture demonstrated his commitment to "the art of commo ...

met William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

and they went on to become leading members of the English Arts and Crafts Movement. When the German critic Hermann Muthesius

Adam Gottlieb Hermann Muthesius (20 April 1861 – 29 October 1927), known as Hermann Muthesius, was a German architect, author and diplomat, perhaps best known for promoting many of the ideas of the English Arts and Crafts movement within German ...

published his admiring and influential study of English domestic architecture, ''Das englische Haus

''The English House'' is a book of design and architectural history written by German architect Hermann Muthesius and first published in German as in 1904. Its three volumes provide a record of the revival of English domestic architecture durin ...

'' (1904), Pugin was all but invisible, yet "it was he ... who invented the English House that Muthesius so admired".

An armoire

A wardrobe or armoire or almirah is a standing closet used for storing clothes. The earliest wardrobe was a chest, and it was not until some degree of luxury was attained in regal palaces and the castles of powerful nobles that separate accommo ...

that he designed (crafted by frequent collaborator John Gregory Crace) is held at the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

. It was shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

, but was not eligible for a medal, as it was shown under Crace's name and he was a judge for the Furniture Class at the exhibition.

On 23 February 2012 the Royal Mail

, kw, Postya Riel, ga, An Post Ríoga

, logo = Royal Mail.svg

, logo_size = 250px

, type = Public limited company

, traded_as =

, foundation =

, founder = Henry VIII

, location = London, England, UK

, key_people = * Keith Williams ...

released a first class stamp featuring Pugin as part of its "Britons of Distinction" series. The stamp image depicts an interior view of the Palace of Westminster. Also in 2012, the BBC broadcast ''God's Own Architect'', an arts documentary program on his achievements hosted by Richard Taylor.

Pugin's principal buildings in the United Kingdom

House designs, with approximate date of design and current condition

* Hall of John Halle,

* Hall of John Halle, Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

(1834) – Restoration of an existing hall of 1470, largely intact but extended prior to and following the 1834 restoration; now in use as the vestibule to a cinema

*St Marie's Grange, Alderbury (1835) – altered; a private house

* Oxburgh Hall (with J.C. Buckler, 1835) – Restoration of a 15th-century fortified manor house, now owned by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

*Derby presbytery (1838) – demolished

* Scarisbrick Hall (1837) – largely intact; a school

*Uttoxeter presbytery (1838) – largely intact; in use

*Keighley presbytery (1838) – altered; in use

*Bishop's House, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

(1840) – demolished

*Warwick Bridge presbytery (1841) – intact with minor alterations; in use

*Clergy House, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

(1841) – largely intact; in use

* Garendon Hall scheme (1841) – not executed

* Bilton Grange (1841) – intact; now a school

*Oxenford Grange farm buildings (1841) – intact; private house and farm

*Cheadle presbytery (1842) – largely intact; now a private house

* Woolwich presbytery (1842) – largely intact; in use

*Brewood presbytery (1842) – largely intact; in use

* St Augustine's Grange ("The Grange"), Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside town in the district of Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to the Census, there was a populati ...

(1843) – restored by the Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British building conservation charity, founded in 1965 by Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or architectural merit and then makes them available for holiday rental. The Trust's headqua ...

*Alton Castle

Alton Castle is a Gothic-revival castle, on a hill above the Churnet Valley, in the village of Alton, Staffordshire, England. The site has been fortified in wood since Saxon times, with a stone castle dating from the 12th century. The current ...

(1843) – intact; a Catholic youth centre

*Alton Towers

Alton Towers Resort ( ) (often referred to as Alton Towers) is a theme park and resort complex in Staffordshire, England, near the village of Alton. The park is operated by Merlin Entertainments Group and incorporates a theme park, water pa ...

– largely intact; used as a theme park

*Oswaldcroft, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

(1844) – altered; a residential home

*Dartington Hall scheme (1845) – unexecuted

*Lanteglos-by-Camelford rectory (1846) – much altered; a hotel

* Rampisham rectory (1846) – unaltered; private house

* Woodchester Park scheme (1846) – unexecuted

*St Thomas of Canterbury Church, Fulham

St Thomas of Canterbury Church, also known as St Thomas's, Rylston Road, is a Roman Catholic parish church in Fulham, central London. Designed in the Gothic Revival style by Augustus Pugin in 1847, the building is Grade II* listed with Historic ...

(1847)

*Fulham presbytery (1847) – intact; in use

*Leighton Hall, Powys

Leighton Hall is an estate located to the east of Welshpool in the historic county of Montgomeryshire, now Powys, in Wales. Leighton Hall is a listed grade I property. It is located on the opposite side of the valley of the river Severn to Powis ...

(1847) – intact; in use

* Banwell Castle (1847) – intact now a hotel and restaurant

*Wilburton Manor House (1848) – largely intact; Stafford Grammar School

Stafford Grammar School is a mixed independent day school at Burton Manor, located on the outskirts of Stafford, the county town of Staffordshire. Founded in 1982, the school inhabits a building built by the Victorian architect Augustus Pugin.

H ...

*Pugin's Hall (1850) – intact, a private house

*St Edmund's College Chapel (1853) – intact, a school and chapel

Institutional designs

*Convent of Mercy,Bermondsey

Bermondsey () is a district in southeast London, part of the London Borough of Southwark, England, southeast of Charing Cross. To the west of Bermondsey lies Southwark, to the east Rotherhithe and Deptford, to the south Walworth and Peckham ...

(1838) – destroyed

* Mount St. Bernard Abbey (1839) – largely intact; in use

*Downside Abbey

Downside Abbey is a Benedictine monastery in England and the senior community of the English Benedictine Congregation. Until 2019, the community had close links with Downside School, for the education of children aged eleven to eighteen. Both ...

schemes (1839 and 1841) – unexecuted

* Convent of Mercy, Handsworth 1840 – largely intact; in use

*St John's Hospital, Alton (1841) – intact; in use

*Convent of St Joseph, school and almshouses, Chelsea, London

Chelsea is an affluent area in west London, England, due south-west of Charing Cross by approximately 2.5 miles. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames and for postal purposes is part of the south-western postal area.

Chelsea histori ...

(1841) – altered; used as a school

*Convent of Mercy, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

(1841 – and from 1847) – demolished

* Spechley school and schoolmaster's house (1841) – intact, now a private house

*Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the ...

, scheme (1843) – unexecuted

*Ratcliffe College (1843) – partially executed; largely intact; in use

*Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

Orphanage (1843) – demolished

* Magdalen College School, Oxford, schemes (1843–44) – unexecuted

*Convent of Mercy, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

(1844) – altered; private flats

*Mercy House and cloisters, Handsworth (1844–45) – cloisters intact; otherwise destroyed

*Cotton College

Cotton College was a Roman Catholic boarding school in Cotton, Staffordshire, United Kingdom. It was also known as ''Saint Wilfrid's College''.

The school buildings were centred on Cotton Hall, a country house used by religious communities fro ...

, Staffordshire (1846) – alterations to older house for use by a religious community, now derelict

*St Anne's Bedehouses, Lincoln, (1847) – intact; in use

*Convent of the Good Shepherd, Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London ...

, London (1848) – demolished

*Convent of St Joseph's, Cheadle (1848) – intact; private house

*King Edward's School, Birmingham

King Edward's School (KES) is an independent day school for boys in the British public school tradition, located in Edgbaston, Birmingham. Founded by King Edward VI in 1552, it is part of the Foundation of the Schools of King Edward VI in Bir ...

(design of parts of interior) (1838) –

Major ecclesiastical designs

*St James's

St James's is a central district in the City of Westminster, London, forming part of the West End. In the 17th century the area developed as a residential location for the British aristocracy, and around the 19th century was the focus of the d ...

, Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spell ...

(1837) – altered

* St Mary's, Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

(1837) – altered

*Oscott College

St Mary's College in New Oscott, Birmingham, often called Oscott College, is the Roman Catholic seminary of the Archdiocese of Birmingham in England and one of the three seminaries of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.

Purpose

Oscott C ...

Chapel (1837–38) – extant

*Our Lady and St Thomas of Canterbury, Dudley

Dudley is a large market town and administrative centre in the county of West Midlands, England, southeast of Wolverhampton and northwest of Birmingham. Historically an exclave of Worcestershire, the town is the administrative centre of the ...

(1838) – altered

*St Anne's, Keighley

Keighley ( ) is a market town and a civil parish

in the City of Bradford Borough of West Yorkshire, England. It is the second largest settlement in the borough, after Bradford.

Keighley is north-west of Bradford city centre, north-west o ...

(1838) – altered and extended

* St Alban's, Macclesfield

Macclesfield is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Bollin in the east of the county, on the edge of the Cheshire Plain, with Macclesfield Forest to its eas ...

(1838) – extant

*St Benedict Abbey ( Oulton Abbey), Stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

, Staffordshire (1854) – complete and in use as a nursing home

*St Marie's, Ducie Street, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

(1838) – not executed

*St Augustine's, Solihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blyth ...

(1838) – altered and extended

*St Marie's, Southport

Southport is a seaside town in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton in Merseyside, England. At the 2001 census, it had a population of 90,336, making it the eleventh most populous settlement in North West England.

Southport lies on the Iris ...

(1838) – altered

* St Mary's Catholic Church, Uttoxeter (1839) – altered

* St Wilfrid's, Hulme

Hulme () is an inner city area and electoral ward of Manchester, England, immediately south of Manchester city centre. It has a significant industrial heritage.

Historically in Lancashire, the name Hulme is derived from the Old Norse word ...

, Manchester (1839) – extant

*Chancel of St John's, Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshir ...

(1839) – extant

* St Chad's, Birmingham (1839) – extant

* St Giles', Cheadle (1840) – extant

*St Oswald's, Liverpool (1840) – only tower remains

* St George's Cathedral, Southwark, London (1840) – almost entirely rebuilt after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

bombing

*Holy Trinity, Radford, Oxfordshire

Radford is a hamlet on the River Glyme in Enstone civil parish about east of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire.

History

In 1086, the manor of Radford, in the hundred of Shipton, Oxfordshire, was one of six manors held by Anchetil de Greye from Wi ...

(1839) – extant

*Our Lady and St Wilfred, Warwick Bridge (1840) – extant

*St Mary's, Brewood

Brewood is an ancient market town in the civil parish of Brewood and Coven, in the South Staffordshire district, in the county of Staffordshire, England. Located around , Brewood lies near the River Penk, eight miles north of Wolverhampton ci ...

(1840) – extant

*St Marie's, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

(1841) – demolished

*St Augustine's, Kenilworth

Kenilworth ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Warwick District in Warwickshire, England, south-west of Coventry, north of Warwick and north-west of London. It lies on Finham Brook, a tributary of the River Sowe, which joins the ...

(1841) – extant

*St Mary's, Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

(1841) – extant, with tower by C. Hansom

* St Barnabas' Cathedral, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

(1841) – extant

* St Mary's, Stockton-on-Tees (1841) – extant

*Jesus Chapel, Ackworth Grange, Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wak ...

(1841) – demolished

* St Peter's, Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained thr ...

(1842) – extended

*St Winifrede's, Shepshed

Shepshed (often known until 1888 as ''Sheepshed'', also ''Sheepshead'' – a name derived from the village being heavily involved in the wool industry) is a town in Leicestershire, England with a population of 13,505 at the 2011 census. It is ...

(1842) – now a private house

* Old St Peter and St Paul's Church, Albury, Albury Park

Albury Park is a country park and Grade II* listed historic country house (Albury Park Mansion) in Surrey, England. It covers over ; within this area is the old village of Albury, which consists of three or four houses and a church. The River Til ...

(mortuary chapel

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

) (1842) – extant

*Reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular architecture, for e ...

of Leeds Cathedral (1842) – transferred to rebuilt cathedral 1902, restored 2007

*Sacred Heart, Cambridge (1843) – dismantled in 1908 and re-erected in St Ives, Cambridgeshire

St Ives is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Huntingdonshire district in Cambridgeshire, England, east of Huntingdon and north-west of Cambridge. St Ives is historically in the historic county of

Huntingdonsh ...

*Our Lady and St Thomas, Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

(1844) – Subsequently, enlarged in stages forming St Mary and St Thomas RC Northampton Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of St Mary and St Thomas is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Northampton, England. It is the seat of the Bishop of Northampton and mother church of the Diocese of Northampton which covers the counties of Northamptonshire, Bed ...

*St Marie's, Wymeswold (restoration) (1844) – extant

* St Wilfrid's, Cotton, Staffordshire Moorlands

Staffordshire Moorlands is a local government district in Staffordshire, England. Its council, Staffordshire Moorlands District Council, is based in Leek and is located between the city of Stoke-on-Trent and the Peak District National Park. The ...

(1844) – extant, but redundant 2012

*St Peter's, Marlow (1845) – extant

*St John the Evangelist ("The Willows"), Kirkham, Lancashire