A History of the Birds of Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''A History of the Birds of Europe, Including all the Species Inhabiting the Western Palearctic Region'' is a nine-volume

Early ornithologies, such as those of

Early ornithologies, such as those of

In an age before modern cameras and binoculars, nineteenth century ornithology was dominated by the collection of eggs taken from the nest and birds obtained through shooting. The corpses were skinned, preserved with arsenical soap, and sometimes stuffed for display.McGhie (2017) pp. 10–11. Ornithologists acquired birds and eggs through their own shooting and collecting activities, by purchases from bird markets, auctions and commercial dealers,McGhie (2017) pp. 78–83. and through exchanges with other collectors.McGhie (2017) pp. 86–87.

Henry Dresser's father, also named Henry, was a successful timber merchant, and sent his son to a school in Ahrensburg near

In an age before modern cameras and binoculars, nineteenth century ornithology was dominated by the collection of eggs taken from the nest and birds obtained through shooting. The corpses were skinned, preserved with arsenical soap, and sometimes stuffed for display.McGhie (2017) pp. 10–11. Ornithologists acquired birds and eggs through their own shooting and collecting activities, by purchases from bird markets, auctions and commercial dealers,McGhie (2017) pp. 78–83. and through exchanges with other collectors.McGhie (2017) pp. 86–87.

Henry Dresser's father, also named Henry, was a successful timber merchant, and sent his son to a school in Ahrensburg near

MeasuringWorth

/ref> Of the 339 copies, 69 were bought by naturalists, 31 by aristocrats, 229 by other private individuals, 67 by dealers and the rest by museums and other institutions. Overseas subscribers accounted for 61 of the purchased sets. Dresser gave 20 further sets, printed on thinner paper and without the plates of illustrations, to those who had contributed information.McGhie (2017) pp. 138–139.

xix–xxi

When choosing binomial names for his species, Dresser kept strictly to chronological priority. Since the first mention might be in an obscure or foreign language journal, this led to changes in the established Latin names of some species, "causing great consternation among his colleagues". The situation was made worse in that many early descriptions were so vague it was impossible to be sure of the species.Ohl (2018) p. 60. Dresser introduced five new names. ''Parus grisescens'' ( Siberian tit), ''Calandrella baetica'' (

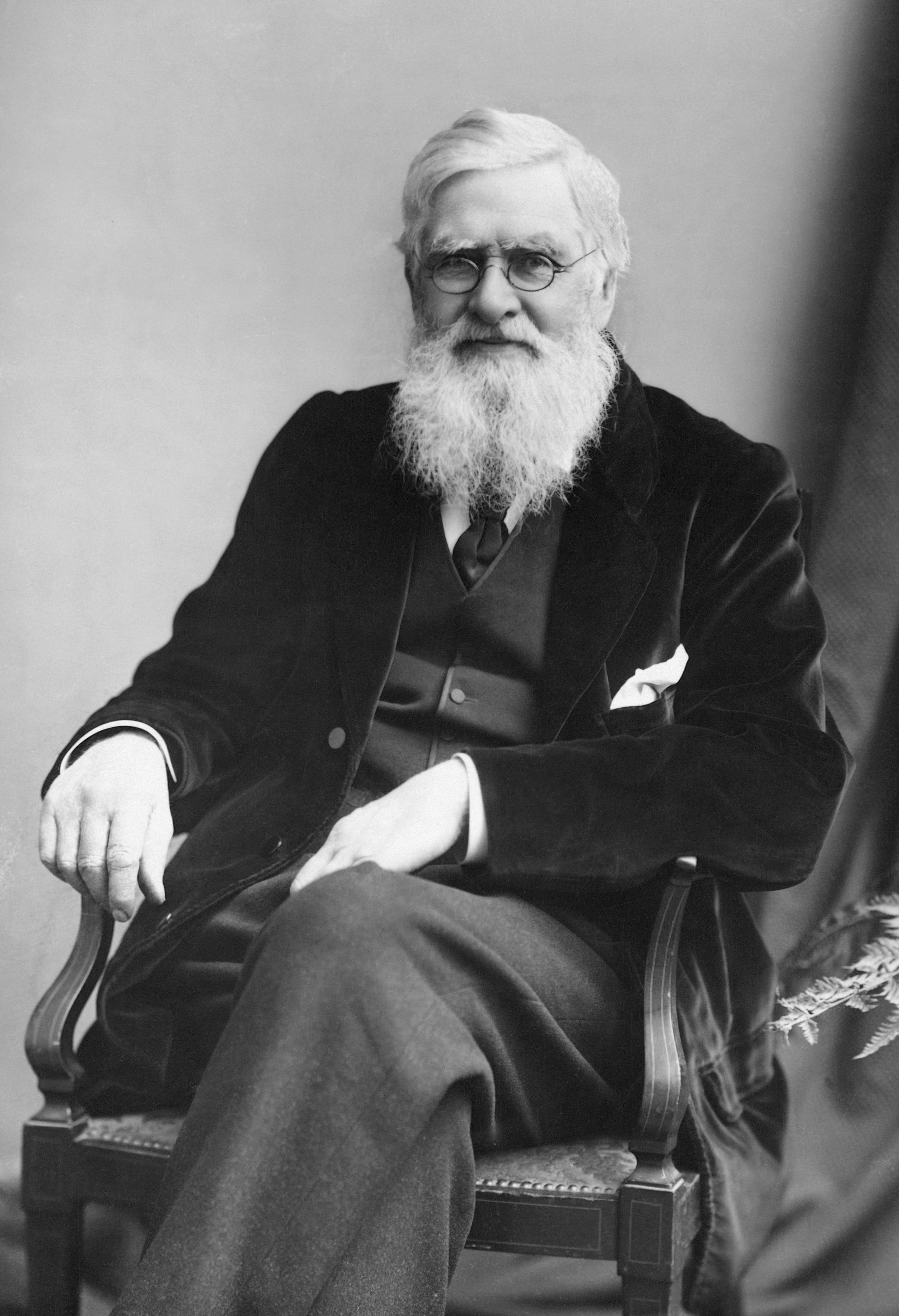

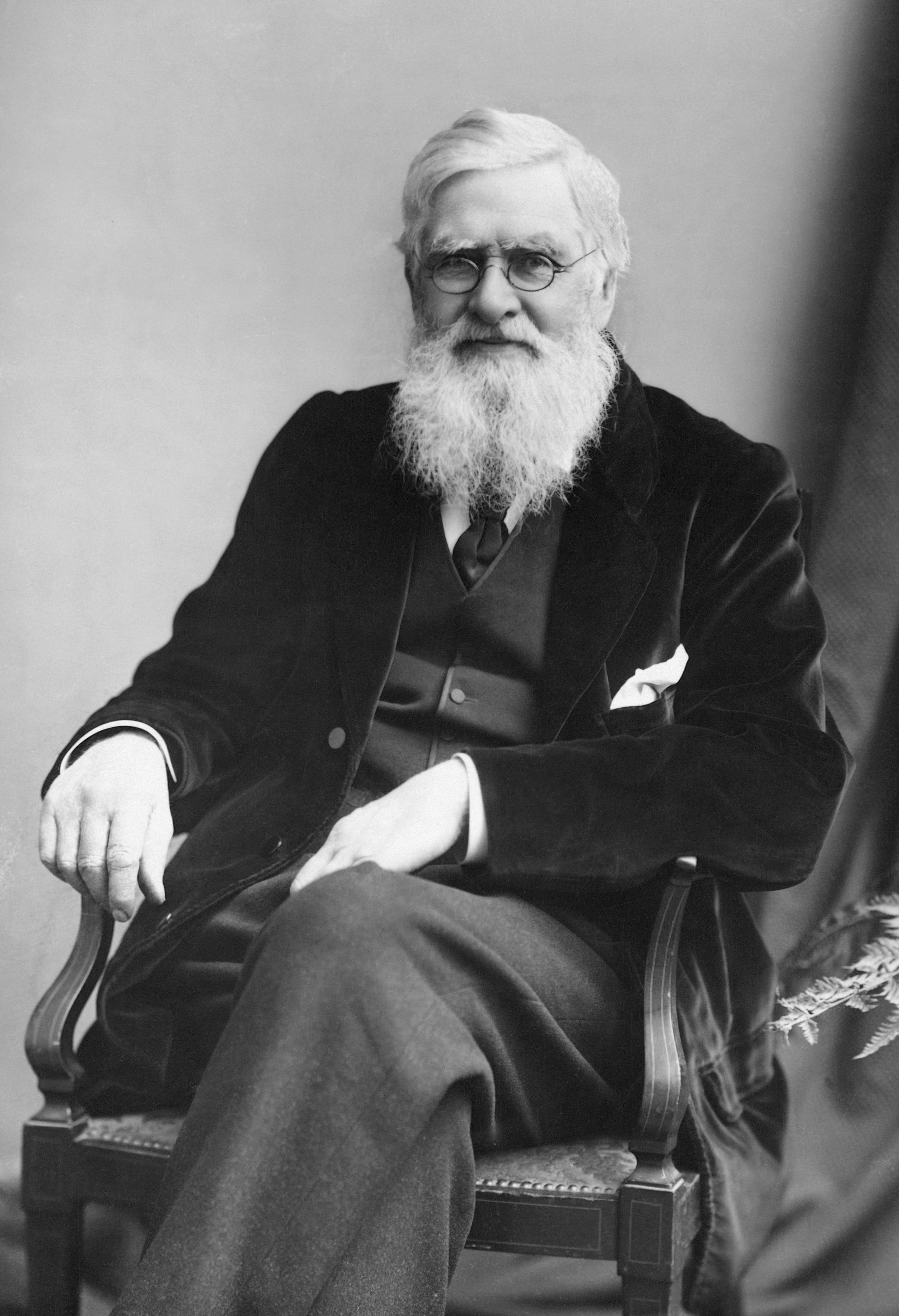

When he came to review ''Birds of Europe'' in 1872, Dresser's old friend Alfred Russel Wallace recommended the work both to general readers and to amateurs, using the latter word in its original sense as a lover of the subject. In a second review in 1875, he said "this beautiful and important work... The energy with which the author has laboured to ensure punctuality in the issue is beyond all praise; and now that about half the work is completed, and we find that the last twelve parts, with figures of nearly 120 species of birds, have appeared within the year, subscribers have every assurance that they will, in due course, possess a finished work."

An outspoken critic of the book was Dresser's former friend, the ornithologist

When he came to review ''Birds of Europe'' in 1872, Dresser's old friend Alfred Russel Wallace recommended the work both to general readers and to amateurs, using the latter word in its original sense as a lover of the subject. In a second review in 1875, he said "this beautiful and important work... The energy with which the author has laboured to ensure punctuality in the issue is beyond all praise; and now that about half the work is completed, and we find that the last twelve parts, with figures of nearly 120 species of birds, have appeared within the year, subscribers have every assurance that they will, in due course, possess a finished work."

An outspoken critic of the book was Dresser's former friend, the ornithologist  Overall, ''Birds of Europe'' was very well received by its contemporary reviewers, as was the ''Supplement'' when it was published. When Dresser died in 1915 aged 77 his obituary in ''

Overall, ''Birds of Europe'' was very well received by its contemporary reviewers, as was the ''Supplement'' when it was published. When Dresser died in 1915 aged 77 his obituary in ''

The ''Birds of Europe'' continued a tradition dating from Ray's time whereby the study and classification of specimens operated largely independently of those observers who studied behaviour and

The ''Birds of Europe'' continued a tradition dating from Ray's time whereby the study and classification of specimens operated largely independently of those observers who studied behaviour and

Throughout his adult life Dresser regularly wrote articles for journals, most frequently ''

Throughout his adult life Dresser regularly wrote articles for journals, most frequently ''

volume 1volume 2volume 3volume 4volume 5volume 6volume 7volume 8volume 9

* * * *

Volume 1Volume 2

*

volume 1 (text)volume 2 (plates and their keys)

(issued in 24 parts beginning in 1905) * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History of the Birds in Europe, A 1896 non-fiction books Natural history books Ornithological handbooks Series of non-fiction books

ornithological

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

book published in parts between 1871 and 1896. It was mainly written by Henry Eeles Dresser

Henry Eeles Dresser (9 May 183828 November 1915) was an English businessman and ornithologist.

Background and early life

Henry Dresser was born in Thirsk, Yorkshire, where his father was the manager of the bank set up by his grandfather. Dres ...

, although Richard Bowdler Sharpe

Richard Bowdler Sharpe (22 November 1847 – 25 December 1909) was an English zoologist and ornithologist who worked as curator of the bird collection at the British Museum of natural history. In the course of his career he published several mo ...

co-authored the earlier volumes. It describes all the bird species reliably recorded in the wild in Europe and adjacent geographical areas with similar fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as ''Biota (ecology ...

, giving their worldwide distribution, variations in appearance and migratory movements.

The pioneering ornithological work of John Ray and Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, la, Franciscus Willughbeius) FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithologist and ichthyologist, and an early student of linguistics and games.

He was born and raised at ...

in the seventeenth century had introduced an effective classification system based on anatomical features, and a dichotomous key

In phylogenetics, a single-access key (also called dichotomous key, sequential key, analytical key, or pathway key) is an identification key where the sequence and structure of identification steps is fixed by the author of the key. At each point i ...

to help readers identify birds. This was followed by other English-language ornithologies, notably John Gould

John Gould (; 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, including Edward Lear, ...

's five-volume ''Birds of Europe'' published between 1832 and 1837. Sharpe, then librarian of the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained the London Zoo, and since 1931 Whipsnade Park.

History

On 29 ...

, had worked closely with Gould and wanted to expand on his work by including all species reliably recorded in Europe, North Africa, parts of the Middle East and the Atlantic archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arc ...

s of Madeira, the Canary Islands and the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. He lacked the resources to undertake this task on his own, so he proposed to Dresser that they work together on this encyclopaedia, using Dresser's extensive collection of birds and their eggs and network of contacts.

The ''Birds of Europe'' was published as 84 quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

parts, each typically containing 56 pages of text and eight plates of illustrations, the latter mainly by the Dutch artist John Gerrard Keulemans

Johannes Gerardus Keulemans (J. G. Keulemans) (8 June 1842 – 29 March 1912) was a Dutch bird illustrator. For most of his life he lived and worked in England, illustrating many of the best-known ornithology books of the nineteenth century.

...

, and bound into volumes when all the parts were published. 339 copies were made, at a cost to each subscriber of £52 10s. Sharpe did not contribute after part 13, and was not listed as an author after part 17. ''Birds of Europe'' was well received by its contemporary reviewers, although a commentator in 2018 considered that Dresser's outdated views and the cost of his books meant that in the long run his works had limited influence. The ''Birds of Europe'' continued a tradition dating from the seventeenth century whereby the study and classification of specimens operated largely independently of those field observers who studied behaviour and ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

, a rift that continued until the 1920s, when the German naturalist Erwin Stresemann

Erwin Friedrich Theodor Stresemann (22 November 1889, in Dresden – 20 November 1972, in East Berlin) was a German naturalist and ornithologist. Stresemann was an ornithologist of extensive breadth who compiled one of the first and most compr ...

integrated the two strands as part of modern zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

.

Background

Early ornithologies, such as those of

Early ornithologies, such as those of Conrad Gessner

Conrad Gessner (; la, Conradus Gesnerus 26 March 1516 – 13 December 1565) was a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. Born into a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland, his father and teachers quickly realised his tale ...

, Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ulisse Aldrovandi (11 September 1522 – 4 May 1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carl Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history st ...

and Pierre Belon

Pierre Belon (1517–1564) was a French traveller, naturalist, writer and diplomat. Like many others of the Renaissance period, he studied and wrote on a range of topics including ichthyology, ornithology, botany, comparative anatomy, architectur ...

, relied for much of their content on the authority of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

and the teachings of the church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

,Birkhead (2011) pp. 18–22.Birkhead (2018) pp. 11–12. and included much extraneous material relating to the species, such as proverb

A proverb (from la, proverbium) is a simple and insightful, traditional saying that expresses a perceived truth based on common sense or experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and use formulaic language. A proverbial phrase or a proverbia ...

s, references in history and literature, or its use as an emblem

An emblem is an abstract or representational pictorial image that represents a concept, like a moral truth, or an allegory, or a person, like a king or saint.

Emblems vs. symbols

Although the words ''emblem'' and '' symbol'' are often us ...

.Kusukawa (2016) p. 306. The arrangement of the species was by alphabetical order in Gessner's ''Historia animalium

''History of Animals'' ( grc-gre, Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν, ''Ton peri ta zoia historion'', "Inquiries on Animals"; la, Historia Animalium, "History of Animals") is one of the major texts on biology by the ancient Gr ...

'', and by arbitrary criteria in most other early works. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

had advocated the advancement of knowledge through observation and experiment, and the English Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and its members such as John Ray, John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the f ...

and Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, la, Franciscus Willughbeius) FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithologist and ichthyologist, and an early student of linguistics and games.

He was born and raised at ...

sought to put the empirical method

Empirical research is research using empirical evidence. It is also a way of gaining knowledge by means of direct and indirect observation or experience. Empiricism values some research more than other kinds. Empirical evidence (the record of ...

into practice,Birkhead (2018) pp. 34–38. including travelling widely to collect specimens and information.Birkhead (2018) pp. 47–50.

The first modern ornithology, intended to describe all the then-known birds worldwide,Birkhead (2018) p. 218. was produced by Ray and Willughby and published in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

as ''Ornithologiae Libri Tres'' (''Three Books of Ornithology'') in 1676,Birkhead (2018) p. 225. and in English, as ''The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton'', in 1678.Birkhead (2018) p. 236. Its innovative features were an effective classification system based on anatomical features, including the bird's beak, feet and overall size, and a dichotomous key

In phylogenetics, a single-access key (also called dichotomous key, sequential key, analytical key, or pathway key) is an identification key where the sequence and structure of identification steps is fixed by the author of the key. At each point i ...

, which helped readers to identify birds by guiding them to the page describing that group.Birkhead (2018) pp. 219–221. The authors also placed an asterisk against species of which they had no first-hand knowledge, and were therefore unable to verify.Birkhead ''et al.'' (2016) p. 292. The commercial success of the ''Ornithology'' is unknown, but it was historically significant,Birkhead (2018) p. 239. influencing writers including René Réamur, Mathurin Jacques Brisson

Mathurin Jacques Brisson (; 30 April 1723 – 23 June 1806) was a French zoologist and natural philosopher.

Brisson was born at Fontenay-le-Comte. The earlier part of his life was spent in the pursuit of natural history; his published works ...

, Georges Cuvier and Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

in compiling their own works.Charmantier ''et al.'' (2016) pp. 377–380.Johanson ''et al.'' (2016) p. 139.

During the early nineteenth century, a number of ornithologies were written in English, including John Gould

John Gould (; 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, including Edward Lear, ...

's five-volume ''Birds of Europe'', which was published between 1832 and 1837.McGhie (2017) pp. 97–100. Richard Bowdler Sharpe

Richard Bowdler Sharpe (22 November 1847 – 25 December 1909) was an English zoologist and ornithologist who worked as curator of the bird collection at the British Museum of natural history. In the course of his career he published several mo ...

, then librarian of the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained the London Zoo, and since 1931 Whipsnade Park.

History

On 29 ...

, had worked closely with Gould and completed some of his books that were still unfinished when he died. He wished to build on Gould's work to include all species reliably recorded in the wild in Europe, expand the geographical range to include North Africa, parts of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

and the Atlantic archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arc ...

s of Madeira, the Canary Islands and the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

(this extended area constitutes the Western Palaearctic

The Western Palaearctic or Western Palearctic is part of the Palaearctic realm, one of the eight biogeographic realms dividing the Earth's surface. Because of its size, the Palaearctic is often divided for convenience into two, with Europe, North ...

realm) and to describe the worldwide distribution, variation and movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

of each of the species. He lacked the resources to undertake this task on his own, so he proposed to businessman and amateur ornithologist Henry Eeles Dresser

Henry Eeles Dresser (9 May 183828 November 1915) was an English businessman and ornithologist.

Background and early life

Henry Dresser was born in Thirsk, Yorkshire, where his father was the manager of the bank set up by his grandfather. Dres ...

that they work together on this great encyclopaedia. Dresser had an extensive collection of European birds and their eggs, and a network of contacts who would allow him to acquire or borrow new specimens. He also had the linguistic skills to translate texts from several European languages.

Dresser and bird collecting

In an age before modern cameras and binoculars, nineteenth century ornithology was dominated by the collection of eggs taken from the nest and birds obtained through shooting. The corpses were skinned, preserved with arsenical soap, and sometimes stuffed for display.McGhie (2017) pp. 10–11. Ornithologists acquired birds and eggs through their own shooting and collecting activities, by purchases from bird markets, auctions and commercial dealers,McGhie (2017) pp. 78–83. and through exchanges with other collectors.McGhie (2017) pp. 86–87.

Henry Dresser's father, also named Henry, was a successful timber merchant, and sent his son to a school in Ahrensburg near

In an age before modern cameras and binoculars, nineteenth century ornithology was dominated by the collection of eggs taken from the nest and birds obtained through shooting. The corpses were skinned, preserved with arsenical soap, and sometimes stuffed for display.McGhie (2017) pp. 10–11. Ornithologists acquired birds and eggs through their own shooting and collecting activities, by purchases from bird markets, auctions and commercial dealers,McGhie (2017) pp. 78–83. and through exchanges with other collectors.McGhie (2017) pp. 86–87.

Henry Dresser's father, also named Henry, was a successful timber merchant, and sent his son to a school in Ahrensburg near Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

to learn German, and another in Gefle (now Gävle) to study Swedish. Henry junior also acquired fluency in Danish, Finnish, French and Norwegian.McGhie (2017) p. 17. Between 1856 and 1862, the younger Dresser's work sent him to Finland on three occasions and to New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

twice, giving him the opportunity to add birds and eggs from these regions to his collection. On his second trip to Finland he became the first person to find a nest and eggs of the waxwing

The waxwings are three species of passerine birds classified in the genus ''Bombycilla''. They are pinkish-brown and pale grey with distinctive smooth plumage in which many body feathers are not individually visible, a black and white eyestripe, ...

,McGhie (2017) pp. 18–21. which helped to establish his reputation as a serious ornithologist.McGhie (2017) p. 73.

In 1863 and 1864, during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Dresser travelled to North America, setting up shop in the Mexican border town of Matamoros, Tamaulipas

Matamoros, officially known as Heroica Matamoros, is a city in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, and the municipal seat of the homonymous municipality. It is on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, directly across the border from ...

, to sell goods that had evaded the Union blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlanti ...

to the Confederacy.McGhie (2017) pp. 35–38. He made the most of the opportunity to add to his bird collection while there, as he did later when he relocated to San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, where he met the prominent American ornithologist Adolphus Lewis Heermann

Adolphus Lewis Heermann (October 21, 1821 – September 27, 1865) was an American doctor, naturalist, ornithologist, and explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and histo ...

.McGhie (2017) pp. 39–45.

Dresser's contacts for acquiring and exchanging specimens included Robert Swinhoe in China, who had 4,000 skins of 600 species, Thomas Blakiston in Japan, Allan Octavian Hume

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829 – 31 July 1912) was a British civil servant, political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was the founder of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hum ...

in India, whose 80,000 skins and 20,000 eggs were the world's largest private collection at the time, and William Blandford, a naturalist and geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althoug ...

working in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

.McGhie (2017) pp. 119–128. He also collaborated with prominent Russians including Nikolay Przhevalsky, Nikolai Severtzov

Nikolai Alekseevich Severtzov (5 November 1827 – 8 February 1885) was a Russian explorer and naturalist.

Severtzov studied at the Moscow University and at the age of eighteen he came into contact with G. S. Karelin and took an interest i ...

and Sergei Buturlin

Sergei Aleksandrovich Buturlin (russian: Серге́й Александрович Бутурлин); 22 September 1872 in Montreux – 22 January 1938 in Moscow was a Russian ornithologist.

A scion of one of the oldest families of Russian nobil ...

. African specimens came from a variety of sources, including colonial administrators and the collections of the Germans Wilhelm Friedrich Hemprich

Wilhelm Friedrich Hemprich (24 June 1796 – 30 June 1825) was a German naturalist and explorer.

Hemprich was born in Glatz (Kłodzko), Prussian Silesia, and studied medicine at Breslau and Berlin. It was in Berlin that he became friends with ...

and Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (19 April 1795 – 27 June 1876) was a German Natural history, naturalist, zoologist, comparative anatomist, geologist, and microscopy, microscopist. Ehrenberg was an Evangelicalism, evangelist and was considered to ...

.McGhie (2017) pp. 133–135. Alfred Newton

Alfred Newton FRS HFRSE (11 June 18297 June 1907) was an English zoologist and ornithologist. Newton was Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Cambridge University from 1866 to 1907. Among his numerous publications were a four-volume ''Dictionar ...

gave his friend Dresser access to a collection of birds from Lapland.McGhie (2017) p. 105. By 1868, Dresser owned 1,200 skins and several thousand eggs.McGhie (2017) p. 92. His final collection, including about 10,000 skins, is now kept at Manchester Museum

Manchester Museum is a museum displaying works of archaeology, anthropology and natural history and is owned by the University of Manchester, in England. Sited on Oxford Road ( A34) at the heart of the university's group of neo-Gothic buildings, ...

, and includes the only known egg of the now-extinct slender-billed curlew

The slender-billed curlew (''Numenius tenuirostris'') is a bird in the wader family Scolopacidae. Isotope analysis suggests the majority of the former population bred in the Kazakh Steppe despite a record from the Siberian swamps, and was mig ...

.

Production

The ''Birds of Europe'' was published as 84quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

parts between 1871 and 1896.McGhie (2017) p. 137. Each part on average contained 56 pages of text and eight plates of illustrations, and took about seven weeks to produce. This meant that for the 11-year duration of the project, Dresser was writing around a page of text a day on top of his commercial employment, and the main illustrator, John Gerrard Keulemans

Johannes Gerardus Keulemans (J. G. Keulemans) (8 June 1842 – 29 March 1912) was a Dutch bird illustrator. For most of his life he lived and worked in England, illustrating many of the best-known ornithology books of the nineteenth century.

...

, was drawing a plate every six days. The publication was financed by subscription, and a year's set of 12 issues cost £6 6s; it was promoted by a prospectus containing sample articles that was sent to potential buyers using the authors' contacts in the scientific societies, including the Zoological Society of London and the British Ornithologists' Union (BOU). By the end of the first year, there were 237 subscribers, including King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

en, Victor Emmanuel Maria Albert Eugene Ferdinand Thomas

, house = Savoy

, father = Charles Albert of Sardinia

, mother = Maria Theresa of Austria

, religion = Roman Catholicism

, image_size = 252px

, succession1 ...

, Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Alfred (Alfred Ernest Albert; 6 August 184430 July 1900) was the sovereign duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 1893 to 1900. He was the second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was known as the Duke of Edinburgh from ...

(by then also Duke of Edinburgh), and the Sikh Maharaja

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, a ...

Duleep Singh

Maharaja Sir Duleep Singh, GCSI (4 September 1838 – 22 October 1893), or Sir Dalip Singh, and later in life nicknamed the "Black Prince of Perthshire", was the last ''Maharaja'' of the Sikh Empire. He was Maharaja Ranjit Singh's youngest son, ...

.

The text and illustrations for the main text and supplement were self-published and printed by Taylor & Francis

Taylor & Francis Group is an international company originating in England that publishes books and academic journals. Its parts include Taylor & Francis, Routledge, F1000 (publisher), F1000 Research or Dovepress. It is a division of Informa ...

of Fleet Street, London. The twelve parts issued each year were bound into temporary volumes, and when all the parts were finally published they were permanently bound into seven volumes using Morocco leather

Morocco leather (also known as Levant, the French Maroquin, or German Saffian from Safi, a Moroccan town famous for leather) is a vegetable-tanned leather known for its softness, pliability, and ability to take color. It has been widely used in ...

with gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

tooling. Parts 83 and 84, containing an introduction, index, references and list of subscribers, were bound as a slim Volume 1, and the 1895–1896 supplement to the main text eventually became a ninth volume.

The complete set's final cost was £52 10s, equivalent to about £5,000 at 2018 values.McGhie (2017) pp. 146–147, calculated usinMeasuringWorth

/ref> Of the 339 copies, 69 were bought by naturalists, 31 by aristocrats, 229 by other private individuals, 67 by dealers and the rest by museums and other institutions. Overseas subscribers accounted for 61 of the purchased sets. Dresser gave 20 further sets, printed on thinner paper and without the plates of illustrations, to those who had contributed information.McGhie (2017) pp. 138–139.

Text

Each part of the book contained birds from differentfamilies

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideal ...

to prevent subscribers attempting to collect only a particularly popular group, such as birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predat ...

or duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form ...

s, the different families coming together only when the articles and plates were reorganised in the final binding. The first part released therefore included birds as diverse as the Eurasian teal

The Eurasian teal (''Anas crecca''), common teal, or Eurasian green-winged teal is a common and widespread duck that breeds in temperate Eurosiberia and migrates south in winter. The Eurasian teal is often called simply the teal due to being th ...

, red-footed falcon, marsh sandpiper

The marsh sandpiper (''Tringa stagnatilis'') is a small wader. It is a rather small shank, and breeds in open grassy steppe and taiga wetlands from easternmost Europe to the Russian Far East. The genus name ''Tringa'' is the New Latin name give ...

and woodchat shrike. Articles for each species included alternative binomial names

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

, a detailed description of both sexes and the juveniles, the bird's range, habitat and habits, and the specimens that had been examined during preparation of the text.McGhie (2017) p. 143.

The taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

used by Dresser was based on a scheme created by Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stori ...

and developed by Philip Sclater

Philip Lutley Sclater (4 November 1829 – 27 June 1913) was an England, English lawyer and zoologist. In zoology, he was an expert ornithologist, and identified the main zoogeographic regions of the world. He was Secretary of the Zoological ...

which used a hierarchical classification using orders and families rather than the arbitrary division into bird groups used by earlier writers. His book started with the passerine

A passerine () is any bird of the order Passeriformes (; from Latin 'sparrow' and '-shaped'), which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds, passerines are distinguished from other orders of birds by th ...

s, rather than the traditional birds of prey.Dresser (1871–1896) ppxix–xxi

When choosing binomial names for his species, Dresser kept strictly to chronological priority. Since the first mention might be in an obscure or foreign language journal, this led to changes in the established Latin names of some species, "causing great consternation among his colleagues". The situation was made worse in that many early descriptions were so vague it was impossible to be sure of the species.Ohl (2018) p. 60. Dresser introduced five new names. ''Parus grisescens'' ( Siberian tit), ''Calandrella baetica'' (

Mediterranean short-toed lark

The Mediterranean short-toed lark (''Alaudala rufescens'') is a small passerine bird found in and around the Mediterranean Basin. It is a common bird with a very wide range from Canary Islands north to the Iberian Peninsula and east throughout N ...

), ''Serinus canonicus'' ( Syrian serin) and ''Anthus seebohmi'' ( Pechora pipit) are now considered to be junior synonyms for the species, and ''Otocorys brandti'' is now ''Eremophila alpestris brandti'', a subspecies of the horned lark

The horned lark or shore lark (''Eremophila alpestris'') is a species of lark in the family Alaudidae found across the northern hemisphere. It is known as "horned lark" in North America and "shore lark" in Europe.

Taxonomy, evolution and systema ...

.McGhie (2011) pp. 88–89.

Dresser and Sharpe initially co-authored the articles, both struggling to keep up to schedule since they were also working full-time. Sharpe resigned as librarian of the Zoological Society late in 1871 to give himself more opportunity to write, but then accepted a post as bird curator at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

in May 1872. His contract meant he was not allowed to have a personal collection, so he sold his skins of African birds to the Museum. Relations between the two authors soon became strained, Sharpe considering that his colleague was too interested in the commercial aspects of the project, rather than the science, and their partnership was dissolved in December 1872. Sharpe did not contribute after part 13, and was not listed as an author after part 17.McGhie (2017) pp. 140–142.

A supplement to the ''Birds of Europe'' was published in nine parts in 1895 and 1896, giving a final count of more than 5,100 pages and 723 plates. The ''Supplement'' covered 114 further species, including 14 discovered since the earlier publication, 22 rare vagrants to Europe and 26 that had been elevated to full species status in the interim. Dresser had also extended the area covered beyond Europe and the Middle East to include neighbouring Persia and western Central Asia, which added many birds from that region.McGhie (2017) p. 186.

Illustrations

The principal illustrator was the Dutch artist John Gerrard Keulemans, who had previously illustrated Sharpe's study ofkingfisher

Kingfishers are a family, the Alcedinidae, of small to medium-sized, brightly colored birds in the order Coraciiformes. They have a cosmopolitan distribution, with most species found in the tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Oceania, ...

s, ''A Monograph of the Alcdinidae''. Keulemans mostly worked from skins rather than life, but attempted to depict the birds realistically. Artists normally painted a picture and then copied it onto a fine limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

slab using a special waxy crayon. The slab was then wetted before adding an oil-based ink, which would be held only by the greasy crayon lines, and copies were printed from the slab. This process was known as lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

.

To reduce costs, Keulemans drew directly on to the limestone instead of first making a painting. Although this was more technically difficult, drawing directly could give a livelier feel to the final illustration, and was also favoured by other contemporary bird artists such as Edward Lear.Uglow (2017) p. 17. The printed plates were hand-coloured, mainly by young women.

Keulemans was also working on other projects, so Dresser had to commission Edward Neale and Joseph Wolfe to draw 28 and 15 plates respectively. Each of the 339 copies produced contained 633 plates, so nearly 215,000 plates were individually coloured.McGhie (2017) pp. 146–147. In addition to the colour plates, there were also monochrome engravings to illustrate interesting features, one example being a drawing of a skull of a Tengmalm's owl to show its asymmetry.McGhie (2017) pp. 139–140.

Reception

When he came to review ''Birds of Europe'' in 1872, Dresser's old friend Alfred Russel Wallace recommended the work both to general readers and to amateurs, using the latter word in its original sense as a lover of the subject. In a second review in 1875, he said "this beautiful and important work... The energy with which the author has laboured to ensure punctuality in the issue is beyond all praise; and now that about half the work is completed, and we find that the last twelve parts, with figures of nearly 120 species of birds, have appeared within the year, subscribers have every assurance that they will, in due course, possess a finished work."

An outspoken critic of the book was Dresser's former friend, the ornithologist

When he came to review ''Birds of Europe'' in 1872, Dresser's old friend Alfred Russel Wallace recommended the work both to general readers and to amateurs, using the latter word in its original sense as a lover of the subject. In a second review in 1875, he said "this beautiful and important work... The energy with which the author has laboured to ensure punctuality in the issue is beyond all praise; and now that about half the work is completed, and we find that the last twelve parts, with figures of nearly 120 species of birds, have appeared within the year, subscribers have every assurance that they will, in due course, possess a finished work."

An outspoken critic of the book was Dresser's former friend, the ornithologist Henry Seebohm

Henry Seebohm (12 July 1832 – 26 November 1895) was an English steel manufacturer, and amateur ornithologist, oologist and traveller.

Biography

Henry was the oldest son of Benjamin Seebohm (1798–1871) who was a wool merchant at Horton G ...

, who criticised the errors in the text and the conservatism of the authors, including their failure to use trinomial nomenclature

In biology, trinomial nomenclature refers to names for taxa below the rank of species. These names have three parts. The usage is different in zoology and botany.

In zoology

In zoological nomenclature, a trinomen (), trinominal name, or ternar ...

. Seebohm was a much more committed supporter of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary theory than Dresser, and believed every local variation of a species should have its own scientific name to demonstrate relationships.McGhie (2017) pp. 176–178. His comments on Dresser and Sharpe include:

and

Overall, ''Birds of Europe'' was very well received by its contemporary reviewers, as was the ''Supplement'' when it was published. When Dresser died in 1915 aged 77 his obituary in ''

Overall, ''Birds of Europe'' was very well received by its contemporary reviewers, as was the ''Supplement'' when it was published. When Dresser died in 1915 aged 77 his obituary in ''Ibis

The ibises () (collective plural ibis; classical plurals ibides and ibes) are a group of long-legged wading birds in the family Threskiornithidae, that inhabit wetlands, forests and plains. "Ibis" derives from the Latin and Ancient Greek word ...

'', an avian science journal, after summarising his life and his major role in scientific societies, went on to say his "most important work is undoubtedly the well-known 'History of the Birds of Europe'... the whole forms a monument of the industry and accuracy of the author." His obituarist, though, added a caveat that "his views on the limits of specific variation and nomenclature would not perhaps commend themselves to present-day workers."

Legacy

The ''Birds of Europe'' continued a tradition dating from Ray's time whereby the study and classification of specimens operated largely independently of those observers who studied behaviour and

The ''Birds of Europe'' continued a tradition dating from Ray's time whereby the study and classification of specimens operated largely independently of those observers who studied behaviour and ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

. The rift between the "museum men" and field ornithologists continued until the 1920s, when the German naturalist Erwin Stresemann

Erwin Friedrich Theodor Stresemann (22 November 1889, in Dresden – 20 November 1972, in East Berlin) was a German naturalist and ornithologist. Stresemann was an ornithologist of extensive breadth who compiled one of the first and most compr ...

integrated the two traditions as part of modern zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

.Birkhead (2011) pp. 44, 49, 51.

The ornithologist Alan Knox commented in 2018 that Dresser's outdated classification scheme and the cost of his books meant that, in the long run, his works were less influential than William Yarrell

William Yarrell (3 June 1784 – 1 September 1856) was an English zoologist, prolific writer, bookseller and naturalist admired by his contemporaries for his precise scientific work.

Yarrell is best known as the author of ''The History of Br ...

's 1843 ''A History of British Birds

''A History of British Birds'' is a natural history book by Thomas Bewick, published in two volumes. Volume 1, ''Land Birds'', appeared in 1797. Volume 2, ''Water Birds'', appeared in 1804. A supplement was published in 1821. The text in ''Lan ...

''. Eventually Dresser's "old guard" views fell out of favour, particularly after World War I,McGhie (2017) pp. 259–260. although his book still attracts the interest of collectors, with first-edition full sets being offered in late 2019 for $27,500 in the US and £19,642 in the UK. A second listing at £22,160 is the US book converted to sterling.

Although Sharpe's contribution to the ''Birds of Europe'' was limited, his involvement facilitated his move to the British Museum and his main work was in classifying and cataloguing the bird collections. He also used his contacts to acquire the egg and skin collections of wealthy collectors and travellers for his museum. When he was appointed in 1872 the museum had 35,000 bird specimens, but had grown to half a million items by the time of his death.

Related works

Throughout his adult life Dresser regularly wrote articles for journals, most frequently ''

Throughout his adult life Dresser regularly wrote articles for journals, most frequently ''The Zoologist

''The Zoologist'' was a monthly natural history magazine established in 1843 by Edward Newman and published in London. Newman acted as editor-in-chief until his death in 1876, when he was succeeded, first by James Edmund Harting (1876–1896) ...

'' and ''Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London

The ''Journal of Zoology'' is a scientific journal concerning zoology, the study of animals. It was founded in 1830 by the Zoological Society of London and is published by Wiley-Blackwell. It carries original research papers, which are targeted t ...

'', although the ''History of the Birds of Europe'' was his first book. He wrote several other ornithological works, namely ''A Monograph of the Meropidae, or Family of the Bee-eaters'' (1884–1886), ''A Monograph of the Coraciidae, or Family of the Rollers'' (1893), the two-volume ''A Manual of Palaearctic Birds'' (1902–1903) and the two-volume ''Eggs of the Birds of Europe'' (1910), which was issued in 24 parts beginning in 1905.McGhie (2017) pp. 293–296.

He had started on the bee-eater

The bee-eaters are a group of non-passerine birds in the family Meropidae, containing three genera and thirty species. Most species are found in Africa and Asia, with a few in southern Europe, Australia, and New Guinea. They are characterised by ...

monograph in 1882, using his own collection of 200 skins of these birds as one of his sources, and by 1883 he was also working on the rollers, adding ''Birds of Europe'' to his workload in the following year.McGhie (2017) p. 173. The 1881 ''A List of European Birds, including all species found in the western palaearctic region'' was based on the ''History of the Birds of Europe'', and may have been a response to criticism from Sclater that the earlier publication was too large.

The ''Manual of Palaearctic Birds'' was largely traditional in its taxonomy, as with its predecessor, but in his treatment of dipper

Dippers are members of the genus ''Cinclus'' in the bird family Cinclidae, so-called because of their bobbing or dipping movements. They are unique among passerines for their ability to dive and swim underwater.

Taxonomy

The genus ''Cinclus'' ...

s he showed a partial acceptance that subspecies could share a common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

, as proposed by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

in ''The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''.McGhie (2017) pp. 207–208. In ''The Eggs of the Birds of Europe'', Dresser used a then-new photographic technique, the three-colour process, to illustrate the subtleties of bird egg markings with colour photographs rather than paintings.McGhie (2017) p. 210.

Notes

References

Cited texts

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Selected bibliography

*volume 1

* * * *

Volume 1

*

volume 1 (text)

(issued in 24 parts beginning in 1905) * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History of the Birds in Europe, A 1896 non-fiction books Natural history books Ornithological handbooks Series of non-fiction books