A Hero of Our Time on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

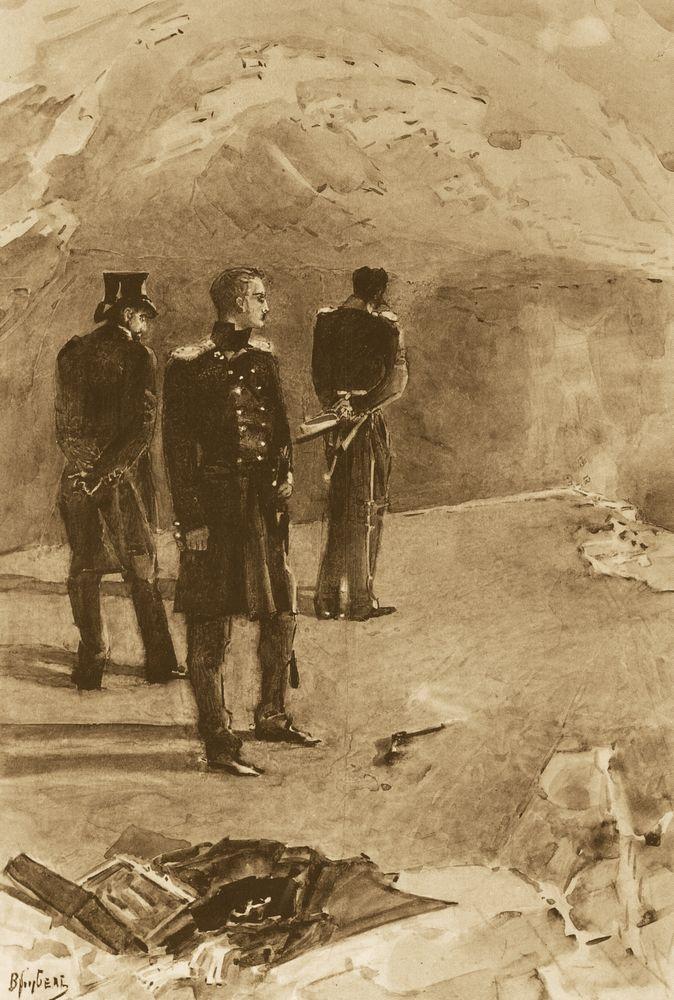

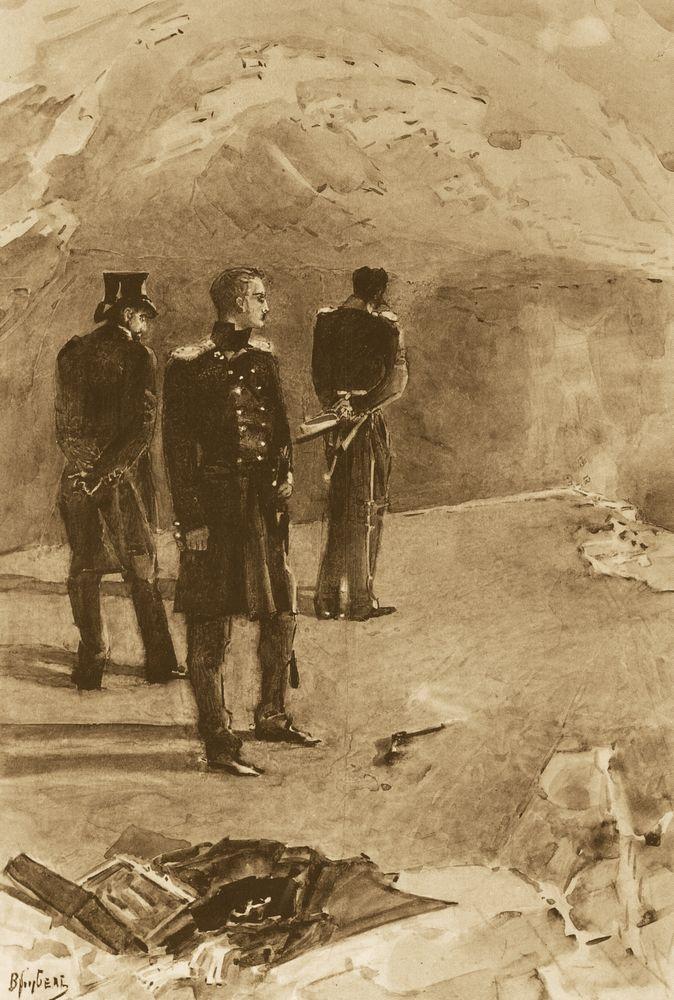

''A Hero of Our Time'' ( rus, Герой нашего времени, links=1, r=Gerój nášego vrémeni, p=ɡʲɪˈroj ˈnaʂɨvə ˈvrʲemʲɪnʲɪ) is a novel by

However, Pechorin's behavior soon changes after Bela gets kidnapped by his enemy Kazbich, and becomes mortally wounded. After 2 days of suffering in delirium Bela spoke of her inner fears and her feelings for Pechorin, who listened without once leaving her side. After her death, Pechorin becomes physically ill, loses weight and becomes unsociable. After meeting with Maxim again, he acts coldly and antisocial, explicating deep depression and disinterest in interaction. He soon dies on his way back from Persia, admitting before that he is sure to never return.

Pechorin described his own personality as self-destructive, admitting he himself doesn't understand his purpose in the world of men. His boredom with life, feeling of emptiness, forces him to indulge in all possible pleasures and experiences, which soon, cause the downfall of those closest to him. He starts to realize this with Vera and Grushnitsky, while the tragedy with Bela soon leads to his complete emotional collapse.

His crushed spirit after this and after the duel with Grushnitsky can be interpreted that he is not the detached character that he makes himself out to be. Rather, it shows that he suffers from his actions. Yet many of his actions are described both by himself and appear to the reader to be arbitrary. Yet this is strange as Pechorin's intelligence is very high (typical of a Byronic hero). Pechorin's explanation as to why his actions are arbitrary can be found in the last chapter where he speculates about fate. He sees his arbitrary behaviour not as being a subconscious reflex to past moments in his life but rather as fate. Pechorin grows dissatisfied with his life as each of his arbitrary actions lead him through more emotional suffering which he represses from the view of others.

However, Pechorin's behavior soon changes after Bela gets kidnapped by his enemy Kazbich, and becomes mortally wounded. After 2 days of suffering in delirium Bela spoke of her inner fears and her feelings for Pechorin, who listened without once leaving her side. After her death, Pechorin becomes physically ill, loses weight and becomes unsociable. After meeting with Maxim again, he acts coldly and antisocial, explicating deep depression and disinterest in interaction. He soon dies on his way back from Persia, admitting before that he is sure to never return.

Pechorin described his own personality as self-destructive, admitting he himself doesn't understand his purpose in the world of men. His boredom with life, feeling of emptiness, forces him to indulge in all possible pleasures and experiences, which soon, cause the downfall of those closest to him. He starts to realize this with Vera and Grushnitsky, while the tragedy with Bela soon leads to his complete emotional collapse.

His crushed spirit after this and after the duel with Grushnitsky can be interpreted that he is not the detached character that he makes himself out to be. Rather, it shows that he suffers from his actions. Yet many of his actions are described both by himself and appear to the reader to be arbitrary. Yet this is strange as Pechorin's intelligence is very high (typical of a Byronic hero). Pechorin's explanation as to why his actions are arbitrary can be found in the last chapter where he speculates about fate. He sees his arbitrary behaviour not as being a subconscious reflex to past moments in his life but rather as fate. Pechorin grows dissatisfied with his life as each of his arbitrary actions lead him through more emotional suffering which he represses from the view of others.

Full text (English translation) of "A Hero of Our Time" at Eldritch Press

. *

Full text of ''A Hero of Our Time'' in the original Russian

Website dedicated to the novel ''A Hero of Our Time''

Website for the Premiere of the English Language Adaptation

Review of ''A Hero of Our Time'' stage production

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hero of Our Time, A 1840 Russian novels Russian-language novels Novels by Mikhail Lermontov Novels set in 19th-century Russia Russian novels adapted into plays Self-reflexive novels

Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (; russian: Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjurʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲɛrməntəf; – ) was a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucas ...

, written in 1839, published in 1840, and revised in 1841.

It is an example of the superfluous man

__NOTOC__

The superfluous man (russian: лишний человек, ''líshniy chelovék'', "extra person") is an 1840s and 1850s Russian literary concept derived from the Byronic hero. It refers to an individual, perhaps talented and capable, w ...

novel, noted for its compelling Byronic hero

The Byronic hero is a variant of the Romantic hero as a type of character, named after the English Romantic poet Lord Byron. Both Byron's own persona as well as characters from his writings are considered to provide defining features to the char ...

(or antihero

An antihero (sometimes spelled as anti-hero) or antiheroine is a main character in a story who may lack conventional heroic qualities and attributes, such as idealism, courage, and morality. Although antiheroes may sometimes perform actions ...

) Pechorin and for the beautiful descriptions of the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

. There are several English translations, including one by Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, Владимир Владимирович Набоков ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bor ...

and Dmitri Nabokov

Dmitri Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: Дми́трий Влади́мирович Набо́ков; May 10, 1934February 22, 2012) was an American opera singer and translator. Born in Berlin, he was the only child of Russian parents: author Vlad ...

in 1958.

Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin

Pechorin is the embodiment of theByronic hero

The Byronic hero is a variant of the Romantic hero as a type of character, named after the English Romantic poet Lord Byron. Both Byron's own persona as well as characters from his writings are considered to provide defining features to the char ...

. Byron's works were of international repute and Lermontov mentions his name several times throughout the novel. According to the Byronic tradition, Pechorin is a character of contradiction. He is both sensitive and cynical

Cynicism is an attitude characterized by a general distrust of the motives of "others". A cynic may have a general lack of faith or hope in people motivated by ambition, desire, greed, gratification, materialism, goals, and opinions that a cynic ...

. He is possessed of extreme arrogance, yet has a deep insight into his own character and epitomizes the melancholy of the Romantic hero

The Romantic hero is a literary archetype referring to a character that rejects established norms and conventions, has been rejected by society, and has themselves at the center of their own existence. The Romantic hero is often the protagonist in ...

who broods on the futility of existence and the certainty of death. Pechorin's whole philosophy concerning existence is oriented towards the nihilistic, creating in him somewhat of a distanced, alienated personality. The name Pechorin is drawn from that of the Pechora River, in the far north, as a homage to Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

's Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Евгений Оне́гин, ромáн в стихáх, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈnʲeɡʲɪn, r=Yevgeniy Onegin, roman v stikhakh) is ...

, named after the Onega River

The Onega (russian: Оне́га; fi, Äänisjoki) is a river in Kargopolsky, Plesetsky, and Onezhsky Districts of Arkhangelsk Oblast in Russia. The Onega connects Lake Lacha with the Onega Bay in the White Sea southwest of Arkhangelsk, flowin ...

.

Pechorin treats women as an incentive for endless conquests and does not consider them worthy of any particular respect. He considers women such as Princess Mary to be little more than pawns in his games of romantic conquest, which in effect hold no meaning in his listless pursuit of pleasure. This is shown in his comment on Princess Mary: "I often wonder why I'm trying so hard to win the love of a girl I have no desire to seduce and whom I'd never marry."

The only contradiction in Pechorin's attitude to women are his genuine feelings for Vera, who loves him despite, and perhaps due to, all his faults. At the end of "Princess Mary" one is presented with a moment of hope as Pechorin gallops after Vera. The reader almost assumes that a meaning to his existence may be attained and that Pechorin can finally realize that true feelings are possible. Yet a lifetime of superficiality and cynicism cannot be so easily eradicated and when fate intervenes and Pechorin's horse collapses, he undertakes no further effort to reach his one hope of redemption: "I saw how futile and senseless it was to pursue lost happiness. What more did I want? To see her again? For what?”

Pechorin's chronologically last adventure was first described in the book, showing the events that explain his upcoming fall into depression and retreat from society, resulting in his self-predicted death. The narrator is Maxim Maximytch telling the story of a beautiful Circassian princess, "Bela", whom Azamat abducts for Pechorin in exchange for Kazbich's horse. Maxim describes Pechorin's exemplary persistence to convince Bela to give herself sexually to him, in which she with time reciprocates. After living with Bela for some time, Pechorin starts explicating his need for freedom, which Bela starts noticing, fearing he might leave her. Though Bela is completely devoted to Pechorin, she says she's not his slave, rather a daughter of a Circassian tribal chieftain, also showing the intention of leaving if he "doesn't love her". Maxim's sympathy for Bela makes him question Pechorin's intentions. Pechorin admits he loves her and is ready to die for her, but "he has a restless fancy and insatiable heart, and that his life is emptier day by day". He thinks his only remedy is to travel, to keep his spirit alive.

However, Pechorin's behavior soon changes after Bela gets kidnapped by his enemy Kazbich, and becomes mortally wounded. After 2 days of suffering in delirium Bela spoke of her inner fears and her feelings for Pechorin, who listened without once leaving her side. After her death, Pechorin becomes physically ill, loses weight and becomes unsociable. After meeting with Maxim again, he acts coldly and antisocial, explicating deep depression and disinterest in interaction. He soon dies on his way back from Persia, admitting before that he is sure to never return.

Pechorin described his own personality as self-destructive, admitting he himself doesn't understand his purpose in the world of men. His boredom with life, feeling of emptiness, forces him to indulge in all possible pleasures and experiences, which soon, cause the downfall of those closest to him. He starts to realize this with Vera and Grushnitsky, while the tragedy with Bela soon leads to his complete emotional collapse.

His crushed spirit after this and after the duel with Grushnitsky can be interpreted that he is not the detached character that he makes himself out to be. Rather, it shows that he suffers from his actions. Yet many of his actions are described both by himself and appear to the reader to be arbitrary. Yet this is strange as Pechorin's intelligence is very high (typical of a Byronic hero). Pechorin's explanation as to why his actions are arbitrary can be found in the last chapter where he speculates about fate. He sees his arbitrary behaviour not as being a subconscious reflex to past moments in his life but rather as fate. Pechorin grows dissatisfied with his life as each of his arbitrary actions lead him through more emotional suffering which he represses from the view of others.

However, Pechorin's behavior soon changes after Bela gets kidnapped by his enemy Kazbich, and becomes mortally wounded. After 2 days of suffering in delirium Bela spoke of her inner fears and her feelings for Pechorin, who listened without once leaving her side. After her death, Pechorin becomes physically ill, loses weight and becomes unsociable. After meeting with Maxim again, he acts coldly and antisocial, explicating deep depression and disinterest in interaction. He soon dies on his way back from Persia, admitting before that he is sure to never return.

Pechorin described his own personality as self-destructive, admitting he himself doesn't understand his purpose in the world of men. His boredom with life, feeling of emptiness, forces him to indulge in all possible pleasures and experiences, which soon, cause the downfall of those closest to him. He starts to realize this with Vera and Grushnitsky, while the tragedy with Bela soon leads to his complete emotional collapse.

His crushed spirit after this and after the duel with Grushnitsky can be interpreted that he is not the detached character that he makes himself out to be. Rather, it shows that he suffers from his actions. Yet many of his actions are described both by himself and appear to the reader to be arbitrary. Yet this is strange as Pechorin's intelligence is very high (typical of a Byronic hero). Pechorin's explanation as to why his actions are arbitrary can be found in the last chapter where he speculates about fate. He sees his arbitrary behaviour not as being a subconscious reflex to past moments in his life but rather as fate. Pechorin grows dissatisfied with his life as each of his arbitrary actions lead him through more emotional suffering which he represses from the view of others.

Cultural references

Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

' novel '' The Fall'' begins with an excerpt from Lermontov's foreword to ''A Hero of Our Time'': "Some were dreadfully insulted, and quite seriously, to have held up as a model such an immoral character as ''A Hero of Our Time''; others shrewdly noticed that the author had portrayed himself and his acquaintances. ''A Hero of Our Time'', gentlemen, is in fact a portrait, but not of an individual; it is the aggregate of the vices of our whole generation in their fullest expression."

In Ian Fleming's '' From Russia with Love'' the plot revolves upon Soviet agent Tatiana Romanova feigning an infatuation with MI6's James Bond and offering to defect to the West provided he'll be sent to pick her up in Istanbul, Turkey. The Soviets elaborate a complex backstory about how she spotted the file about the English spy during her clerical work at SMERSH

SMERSH (russian: СМЕРШ) was an umbrella organization for three independent counter-intelligence agencies in the Red Army formed in late 1942 or even earlier, but officially announced only on 14 April 1943. The name SMERSH was coined by Josep ...

headquarters and became smitten with him, making her state that his picture made her think of Lermontov's Pechorin. The fact that Pechorin was anything but a 'hero' or even a positive character at all in Lermontov's narration stands to indicate Fleming's wry self-deprecating wit about his most famous creation; the irony is lost, however, on western readers not familiar with Lermontov's work.

In Ingmar Bergman's 1963 film '' The Silence'', the young son is seen reading the book in bed. In the opening sequence of Bergman's next film, ''Persona

A persona (plural personae or personas), depending on the context, is the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional character. The word derives from Latin, where it originally referred to a theatr ...

'' (1966), the same child actor is seen waking in what appears to be a mortuary and reaching for the same book.

Claude Sautet

Claude Sautet (23 February 1924 – 22 July 2000) was a French film director and screenwriter.

He was a chronicler of post-war French society. He made a total of five films with his favorite actress Romy Schneider.

Biography

Born in Montrou ...

's film ''A Heart in Winter

''A Heart in Winter'' (french: Un cœur en hiver) is a French film which was released in 1992. It stars Emmanuelle Béart, Daniel Auteuil and André Dussollier. It was chosen to compete at the 49th Venice International Film Festival, where it won ...

'' (''Un cœur en hiver'') was said to be based on "his memories of" the Princess Mary section. The relationship with Lermontov's work is quite loose – the film takes place in contemporary Paris, where a young violin repairer (played by Daniel Auteuil

Daniel Auteuil (; born 24 January 1950) is a French actor and director who has appeared in a wide range of film genres, including period dramas, romantic comedies, and crime thrillers. In 1996 he won the Best Actor Award at the Cannes Film Fest ...

) seeks to seduce his business partner's girlfriend, a gifted violinist named Camille, into falling for his carefully contrived charms. He does this purely for the satisfaction of gaining control of her emotionally, while never loving her sincerely. He is a modern-day Pechorin.

Quotations

*"My whole life has been merely a succession of miserable and unsuccessful denials of feelings or reason." *"...I am not capable of close friendship: of two close friends, one is always the slave of the other, although frequently neither of them will admit it. I cannot be a slave, and to command in such circumstances is a tiresome business, because one must deceive at the same time." *"Afraid of being judged, I buried my finer feelings in the depths of my heart and they died there." *"It is difficult to convince women of something; one must lead them to believe that they have convinced themselves." *"What of it? If I die, I die. It will be no great loss to the world, and I am thoroughly bored with life. I am like a man yawning at a ball; the only reason he does not go home to bed is that his carriage has not arrived yet." *"When I think of imminent and possible death, I think only of myself; some do not even do that. Friends, who will forget me tomorrow, or, worse still, who will weave God knows what fantastic yarns about me; and women, who in the embrace of another man will laugh at me in order that he might not be jealous of the departed—what do I care for them?" *"Women! Women! Who will understand them? Their smiles contradict their glances, their words promise and lure, while the sound of their voices drives us away. One minute they comprehend and divine our most secret thoughts, and the next, they do not understand the clearest hints." *"There are two men within me – one lives in the full sense of the word, the other reflects and judges him. In an hour's time the first may be leaving you and the world for ever, and the second? ... the second? ..." *"To cause another person suffering or joy, having no right to so—isn't that the sweetest food of our pride? What is happiness but gratified pride?" *"I'll hazard my life, even my honor, twenty times, but I will not sell my freedom. Why do I value it so much? What am I preparing myself for? What do I expect from the future? in fact, nothing at all." * Grushnitski (to Pechorin): "Mon cher, je haïs les hommes pour ne pas les mépriser car autrement la vie serait une farce trop dégoûtante." ("My friend, I hate people to avoid despising them because otherwise, life would become too disgusting a farce.") * Pechorin (replying to Grushnitski): "Mon cher, je méprise les femmes pour ne pas les aimer car autrement la vie serait un mélodrame trop ridicule" ("My friend, I despise women to avoid loving them because otherwise, life would become too ridiculous a melodrama.") *"Passions are merely ideas in their initial stage." *"I was prepared to love the whole world . . . I learned to hate." *"Whether I am a fool or a villain I know not; but this is certain, I am also most deserving of pity – perhaps more so than she. My soul has been spoiled by the world, my imagination is unquiet, my heart insatiate. To me everything is of little moment. I have become as easily accustomed to grief as to joy, and my life grows emptier day by day." *"That is just like human beings! They are all alike; though fully aware in advance of all the evil aspects of a deed, they aid and abet and even give their approbation to it when they see there is no other way out—and then they wash their hands of it and turn away with disapproval from him who dared assume the full burden of responsibility. They are all alike, even the kindest and wisest of them!" *"Women love only the men they don't know."Stage adaptation

In 2011 Alex Mcsweeney adapted the novel into an English-language playscript. Previewed at the International Youth Arts Festival in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, UK in July, it subsequently premiered in August of the same year at Zoo Venues in the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Critics received it positively, generally giving 4- and 5-star reviews. In 2014, German stage director Kateryna Sokolova adapted the novel focusing on its longest novella, ''Princess Mary''. The play, directed by Kateryna Sokolova, premiered at the Schauspielhaus Zürich on 28 May. The production received universal acclaim, especially praising it for not having lost "neither the linguistic finesse nor the social paralysis of Lermontov’s Zeitgeist", both of which constitute the novel's Byronic character. On July 22, 2015, The Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow premiered a ballet adaptation of ''Hero of Our Time''. The ballet was choreographed by San Francisco Ballet's Choreographer in Residence, Yuri Possokhov, and directed byKirill Serebrennikov

Kirill Semyonovich Serebrennikov (russian: Кирилл Семёнович Серебренников; born 7 September 1969) is a Russian stage and film director and theatre designer. Since 2012, he has been the artistic director of the Gogol ...

- who is also the author of the libretto. The score was commissioned purposefully for this production and composed by Ilya Demutsky. This production focuses on three novellas from Lermontov's novel - Bela, Taman, and Princess Mary.

Bibliography of English translations

Translations:Translations from Longworth on as cited in COPAC catalogue. #''Sketches of Russian life in the Caucasus. By a Russe, many years resident amongst the various mountain tribes.'' London: Ingram, Cook and Co., 1853. 315 pp. "The illustrated family novelist" series, #2. (a liberal translation with changed names of the heroes; "Taman" not translated). #''The hero of our days.'' Transl. by Theresa Pulszky. London: T. Hodgson, 1854. 232 pp. "The Parlour Library". Vol.112. ("Fatalist" not translated). #''A hero of our own times. Now first transl. into English.'' London: Bogue, 1854. 231 pp., ill. (the first full translation of the novel by an anonymous translator). #''A hero of our time.'' Transl. by R. I. Lipmann. London: Ward and Downey, 1886. XXVIII, 272 pp. ("Fatalist" not translated). #''Taman''. In: ''Tales from the Russian. Dubrovsky by Pushkin. New year's eve by Gregorowitch. Taman by Lermontoff.'' London: The Railway and general automatic library, 1891, pp. 229–251. #''Russian reader: Lermontof's modern hero, with English translation and biographical sketch by Ivan Nestor-Schnurmann.'' Cambridge: Univ. press, 1899. XX, 403 pp. (a dual language edition; "Fatalist" not translated) #''Maxim Maximich.'' — In: Wiener L. ''Anthology of Russian literature''. T. 2, part 2. London—N.Y., 1903, pp. 157–164. (a reduced version of the "Maxim Maximich" chapter). #''The heart of a Russian.'' Transl. by J. H. Wisdom and Marr Murray. London: Herbert and Daniel, 1912. VII, 335 pp. (also published in 1916 by Hodder and Stoughton, London—N.Y.—Toronto). #''The duel. Excerpt from The hero of our own time.'' Transl. by T. Pulszky. — In: ''A Russian anthology in English''. Ed. by C. E. B. Roberts. N. Y.: 1917, pp. 124–137. #''A traveling episode''. — In: ''Little Russian masterpieces''. Transl. by Z. A. Ragozin. Vol. 1. N. Y.: Putnam, 1920, pp. 165–198. (an excerpt from the novel). #''A hero of nowadays''. Transl. by John Swinnerton Phillimore. London: Nelson, 1924. #''Taman. — In: Chamot A. ''Selected Russian short stories''. Transl. by A. E. Chamot. London, 1925—1928, pp. 84—97. #''A hero of our time''. Transl. by Reginald Merton. Mirsky. London: Allan, 1928. 247 pp. #''Fatalist. Story.'' Transl. by G.A. Miloradowitch. — In: ''Golden Book Magazine''. Vol. 8. N. Y., 1928, pp. 491—493. #''A hero of our own times''. Transl. by Eden and Cedar Paul for the Lermontov centenary. London: Allen and Unwin, 1940. 283 pp. (also published by Oxford Univ. Press, London—N.Y., 1958). #''Bela''. Transl. by Z. Shoenberg and J. Domb. London: Harrap, 1945. 124 pp. (a dual language edition). #''A hero of our time''. Transl. by Martin Parker. Moscow: Foreign languages publ. house, 1947. 224 pp., ill. (republished in 1951 and 1956; also published by Collet's Holdings, London, 1957). #''A hero of our time. A novel.'' Transl. byVladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, Владимир Владимирович Набоков ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bor ...

in collab. with Dmitri Nabokov

Dmitri Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: Дми́трий Влади́мирович Набо́ков; May 10, 1934February 22, 2012) was an American opera singer and translator. Born in Berlin, he was the only child of Russian parents: author Vlad ...

. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1958. XI, 216 pp. "Doubleday Anchor Books".

#''A Lermontov reader''. Ed., transl., and with an introd. by Guy Daniels. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1965.

#''A hero of our time''. Transl. with an introduction by Paul Foote. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1966.

#''Major poetical works''. Transl., with an introduction and commentary by Anatoly Liberman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

#''Vadim''. Transl. by Helena Goscilo. Ann Arbor: Ardis Publishers, 1984.

#''A hero of our time''. Transl. with an introduction and notes by Natasha Randall; foreword by Neil Labute. New York: Penguin, 2009.

#''A hero of our time''. Translated by Philip Longworth. With an afterword by William E. Harkins, London, 1964, & New York : New American Library, 1964

#''A hero of our time''. Transl. by Martin Parker, revised and edited by Neil Cornwell, London: Dent, 1995

#''A hero of our time''. Transl. by Alexander Vassiliev, London: Alexander Vassiliev 2010. (a dual language edition).

#''A hero of our time''. Transl. by Nicholas Pasternak Slater, Oxford World's Classics, 2013.

See also

*Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

* Tragic hero

A tragic hero is the protagonist of a tragedy. In his ''Poetics'', Aristotle records the descriptions of the tragic hero to the playwright and strictly defines the place that the tragic hero must play and the kind of man he must be. Aristotle ba ...

References

Further reading

*External links

Full text (English translation) of "A Hero of Our Time" at Eldritch Press

. *

Full text of ''A Hero of Our Time'' in the original Russian

Website dedicated to the novel ''A Hero of Our Time''

Website for the Premiere of the English Language Adaptation

Review of ''A Hero of Our Time'' stage production

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hero of Our Time, A 1840 Russian novels Russian-language novels Novels by Mikhail Lermontov Novels set in 19th-century Russia Russian novels adapted into plays Self-reflexive novels