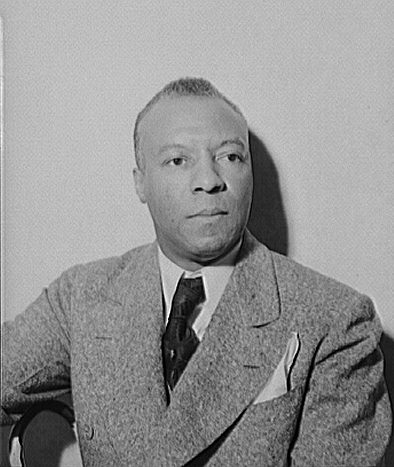

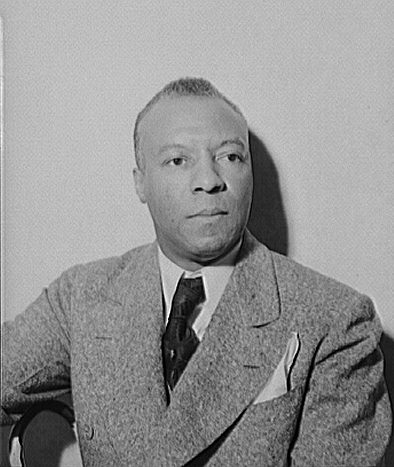

A. Philip Randolph on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American

In New York, Randolph became familiar with socialism and the ideologies espoused by the

In New York, Randolph became familiar with socialism and the ideologies espoused by the

American National Biography Online, February 2000.

/ref> felt betrayed because Roosevelt's order applied only to banning discrimination within war industries and not the armed forces. Nonetheless, the Fair Employment Act is generally considered an important early civil rights victory. And the movement continued to gain momentum. In 1942, an estimated 18,000 blacks gathered at Madison Square Garden to hear Randolph kick off a campaign against discrimination in the military, in war industries, in government agencies, and in labor unions. Following passage of the Act, during the Philadelphia transit strike of 1944, the government backed African-American workers' striking to gain positions formerly limited to white employees. Buoyed by these successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of African Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished

Buoyed by these successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of African Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished

* In 1942, the

* In 1942, the

*

*

A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum

A. Philp Randolph Institute

The Senior Constituency Group of the *

AFL-CIO Labor History Biography of Randolph

* * A. Philip Randolph's

Part 1

*

Part 2

A. Philip Randolph Collected Papers

held by th

Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Documentaries

10,000 Black Men Named George

entry from the

A. Philip Randolph Exhibit

at the

A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs and Freedom

86 minutes, Producer:

labor unionist

The Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA) was an association of trade unionists founded by Edward Carson in June 1918, aligned with the Unionism in Ireland, Ulster Unionists in Ireland. Members were known as Labour Unionists. In Great Britai ...

and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Founded in 1925, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The BSCP gathered a membership of 18,000 passenger railwa ...

, the first successful African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

led labor union. In the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, Randolph was a prominent voice. His continuous agitation with the support of fellow labor rights activists against racist unfair labor practices, eventually helped lead President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941, banning discrimination in the defense industries during World War II. The group then successfully maintained pressure, so that President Harry S. Truman, proposed a new Civil Rights Act, and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 in 1948, promoting fair employment, anti-discrimination policies in federal government hiring, and ending racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in the armed services.

Randolph was born and raised in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

. Although he was able to attain a good education in his community at Cookman Institute, he did not see a future for himself in the discriminatory Jim Crow era south, and moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

just before the Great Migration. There he became convinced that overcoming racism required collective action and he was drawn to socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

and workers' rights. He unsuccessfully ran for state office on the socialist ticket in the early twenties, but found more success in organizing for African American workers' rights.

In 1963, Randolph was the head of the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic righ ...

, which was organized by Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Rustin worked with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement, ...

, at which Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

delivered his " I Have A Dream" speech. Randolph inspired the "Freedom Budget", sometimes called the "Randolph Freedom budget", which aimed to deal with the economic problems facing the black community, it was published by the Randolph Institute in January 1967 as " A Freedom Budget for All Americans".

Biography

Early life and education

Philip Randolph was born April 15, 1889, in Crescent City, Florida, the second son of James William Randolph, a tailor and minister in anAfrican Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

, and Elizabeth Robinson Randolph, a skilled seamstress

A dressmaker, also known as a seamstress, is a person who makes custom clothing for women, such as dresses, blouses, and evening gowns. Dressmakers were historically known as mantua-makers, and are also known as a modiste or fabrician.

Not ...

. In 1891, the family moved to Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

, which had a thriving, well-established African-American community.

From his father, Randolph learned that color was less important than a person's character and conduct. From his mother, he learned the importance of education and of defending oneself physically against those who would seek to hurt one or one's family, if necessary. Randolph remembered vividly the night his mother sat in the front room of their house with a loaded shotgun across her lap, while his father tucked a pistol under his coat and went off to prevent a mob from lynching a man at the local county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposes Chambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

jail.

Asa and his brother, James, were superior students. They attended the Cookman Institute in East Jacksonville, the only academic high school in Florida for African Americans. Asa excelled in literature, drama, and public speaking; he also starred on the school's baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

team, sang solos with the school choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which sp ...

, and was valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

of the 1907 graduating class.

After graduation, Randolph worked odd jobs and devoted his time to singing, acting, and reading. Reading W. E. B. Du Bois' ''The Souls of Black Folk

''The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches'' is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

The book contains several essays on r ...

'' convinced him that the fight for social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within a specific society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and ...

was most important. Barred by discrimination from all but manual jobs in the South, Randolph moved to New York City in 1911, where he worked at odd jobs and took social sciences courses at City College.Pfeffer, Paula F. (2000). "Randolph; Asa Philip". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

Marriage and family

In 1913, Randolph courted and married Lucille Campbell Green, a widow,Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

graduate, and entrepreneur who shared his socialist politics. She earned enough money to support them both. The couple had no children.

Early career

Shortly after Randolph's marriage, he helped organize theShakespearean

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

Society in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

. With them he played the roles of Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

, Othello, and Romeo

Romeo Montague () is the male protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Romeo and Juliet''. The son of Lord Montague and his wife, Lady Montague, he secretly loves and marries Juliet, a member of the rival House of Capulet, through a priest ...

, among others. Randolph aimed to become an actor but gave up after failing to win his parents' approval. In New York, Randolph became familiar with socialism and the ideologies espoused by the

In New York, Randolph became familiar with socialism and the ideologies espoused by the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

. He met Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

Law student Chandler Owen, and the two developed a synthesis of Marxist economics and the sociological ideas of Lester Frank Ward, arguing that people could only be free if not subject to economic deprivation. At this point, Randolph developed what would become his distinctive form of civil rights activism, which emphasized the importance of collective action as a way for black people to gain legal and economic equality. To this end, he and Owen opened an employment office in Harlem to provide job training for southern migrants and encourage them to join trade unions.

Like others in the labor movement, Randolph favored immigration restriction. He opposed African Americans' having to compete with people willing to work for low wages. Unlike other immigration restrictionists, however, he rejected the notions of racial hierarchy that became popular in the 1920s.

In 1917, Randolph and Chandler Owen founded '' The Messenger'' with the help of the Socialist Party of America. It was a radical monthly magazine, which campaigned against lynching, opposed U.S. participation in World War I, urged African Americans to resist being drafted, to fight for an integrated society, and urged them to join radical unions. The Department of Justice called ''The Messenger'' "the most able and the most dangerous of all the Negro publications." When ''The Messenger'' began publishing the work of black poets and authors, a critic called it "one of the most brilliantly edited magazines in the history of Negro journalism."

Soon thereafter, however, the editorial staff of ''The Messenger'' became divided by three issues – the growing rift between West Indian and African Americans, support for the Bolshevik revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

, and support for Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

's Back-to-Africa movement

The back-to-Africa movement was based on the widespread belief among some European Americans in the 18th and 19th century United States that African Americans would want to return to the continent of Africa. In general, the political movement wa ...

. In 1919, most West Indian radicals joined the new Communist Party, while African-American leftists – Randolph included – mostly supported the Socialist Party. The infighting left ''The Messenger'' short of financial support, and it went into decline.

Randolph ran on the Socialist Party ticket for New York State Comptroller in 1920, and for Secretary of State of New York

The secretary of state of New York is a cabinet officer in the government of the U.S. state of New York who leads the Department of State (NYSDOS).

The current secretary of state of New York is Robert J. Rodriguez, a Democrat.

Duties

The secre ...

in 1922, unsuccessfully.

Union organizer

Randolph's first experience withlabor organization

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

came in 1917, when he organized a union of elevator operators in New York City. In 1919 he became president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America, a union which organized among African-American shipyard and dock workers in the Tidewater region of Virginia

Tidewater refers to the north Atlantic coastal plain region of the United States of America.

Definition

Culturally, the Tidewater region usually includes the low-lying plains of southeast Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, southern Maryl ...

. The union dissolved in 1921, under pressure from the American Federation of Labor.

His greatest success came with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), who elected him president in 1925. This was the first serious effort to form a labor institution for employees of the Pullman Company, which was a major employer of African Americans. The railroads had expanded dramatically in the early 20th century, and the jobs offered relatively good employment at a time of widespread racial discrimination. Because porters were not unionized, however, most suffered poor working conditions and were underpaid.

Under Randolph's direction, the BSCP managed to enroll 51 percent of porters within a year, to which Pullman responded with violence and firings. In 1928, after failing to win mediation under the Watson-Parker Railway Labor Act

The Railway Labor Act is a United States federal law on US labor law that governs labor relations in the railroad and airline industries. The Act, enacted in 1926 and amended in 1934 and 1936, seeks to substitute bargaining, arbitration, and media ...

, Randolph planned a strike. This was postponed after rumors circulated that Pullman had 5,000 replacement workers ready to take the place of BSCP members. As a result of its perceived ineffectiveness membership of the union declined; by 1933 it had only 658 members and electricity and telephone service at headquarters had been disconnected because of nonpayment of bills.

Fortunes of the BSCP changed with the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

in 1932. With amendments to the Railway Labor Act

The Railway Labor Act is a United States federal law on US labor law that governs labor relations in the railroad and airline industries. The Act, enacted in 1926 and amended in 1934 and 1936, seeks to substitute bargaining, arbitration, and media ...

in 1934, porters were granted rights under federal law. Membership in the Brotherhood jumped to more than 7,000. After years of bitter struggle, the Pullman Company finally began to negotiate with the Brotherhood in 1935, and agreed to a contract with them in 1937. Employees gained $2,000,000 in pay increases, a shorter workweek, and overtime pay. Randolph maintained the Brotherhood's affiliation with the American Federation of Labor through the 1955 AFL-CIO merger.

Civil rights leader

Through his success with the BSCP, Randolph emerged as one of the most visible spokespeople for African-American civil rights. In 1941, he,Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Rustin worked with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement, ...

, and A. J. Muste

Abraham Johannes Muste ( ; January 8, 1885 – February 11, 1967) was a Dutch-born American clergyman and political activist. He is best remembered for his work in the labor movement, pacifist movement, antiwar movement, and civil rights movemen ...

proposed a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in war industries, an end to segregation, access to defense employment, the proposal of an anti-lynching law and of the desegregation of the American Armed forces. Randolph's belief in the power of peaceful direct action was inspired partly by Mahatma Gandhi's success in using such tactics against British occupation in India. Randolph threatened to have 50,000 blacks march on the city; it was cancelled after President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

issued Executive Order 8802, or the Fair Employment Act. Some activists, including Rustin,Melvyn Dubofsky. "Rustin, Bayard"American National Biography Online, February 2000.

/ref> felt betrayed because Roosevelt's order applied only to banning discrimination within war industries and not the armed forces. Nonetheless, the Fair Employment Act is generally considered an important early civil rights victory. And the movement continued to gain momentum. In 1942, an estimated 18,000 blacks gathered at Madison Square Garden to hear Randolph kick off a campaign against discrimination in the military, in war industries, in government agencies, and in labor unions. Following passage of the Act, during the Philadelphia transit strike of 1944, the government backed African-American workers' striking to gain positions formerly limited to white employees.

Buoyed by these successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of African Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished

Buoyed by these successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of African Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in the armed forces through Executive Order 9981

Executive Order 9981 was issued on July 26, 1948, by President Harry S. Truman. This executive order abolished discrimination "on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin" in the United States Armed Forces, and led to the re-integra ...

.

In 1950, along with Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the ...

, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, and, Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council, Randolph founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). LCCR has been a major civil rights coalition. It coordinated a national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Randolph and Rustin also formed an important alliance with Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

In 1957, when schools in the south resisted school integration following ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'', Randolph organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom with Martin Luther King Jr. In 1958 and 1959, Randolph organized Youth Marches for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C. At the same time, he arranged for Rustin to teach King how to organize peaceful demonstrations in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

and to form alliances with progressive whites. The protests directed by James Bevel in cities such as Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

and Montgomery provoked a violent backlash by police and the local Ku Klux Klan throughout the summer of 1963, which was captured on television and broadcast throughout the nation and the world. Rustin later remarked that Birmingham "was one of television's finest hours. Evening after evening, television brought into the living-rooms of America the violence, brutality, stupidity, and ugliness of Eugene "Bull" Connor's effort to maintain racial segregation."Jervis Anderson, ''Bayard Rustin: Troubles I've Seen: A Biography''. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, p. 244. Partly as a result of the violent spectacle in Birmingham, which was becoming an international embarrassment, the Kennedy administration drafted civil rights legislation aimed at ending Jim Crow once and for all.

Randolph finally realized his vision for a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

on August 28, 1963, which attracted between 200,000 and 300,000 to the nation's capital. The rally is often remembered as the high-point of the Civil Rights Movement, and it did help keep the issue in the public consciousness. However, when President Kennedy was assassinated three months later, Civil Rights legislation was stalled in the Senate. It was not until the following year, under President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, that the Civil Rights Act was finally passed. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Although King and Bevel rightly deserve great credit for these legislative victories, the importance of Randolph's contributions to the Civil Rights Movement is large.

Religion

Randolph avoided speaking publicly about his religious beliefs to avoid alienating his diverse constituencies. Though he is sometimes identified as an atheist, particularly by his detractors, Randolph identified with theAfrican Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

he was raised in. He pioneered the use of prayer protests, which became a key tactic of the civil rights movement. In 1973, he signed the Humanist Manifesto II.

Death

Randolph died in his Manhattan apartment on May 16, 1979. For several years prior to his death, he had a heart condition and high blood pressure. He had no known living relatives, as his wife Lucille had died in 1963, before the March on Washington.Awards and accolades

* In 1942, the

* In 1942, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

awarded Randolph the Spingarn Medal.

* In 1953, the IBPOEW (Black Elks) awarded him their Elijah P. Lovejoy Medal, given "to that American who shall have worked most successfully to advance the cause of human rights, and for the freedom of Negro people."

* On September 14, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Randolph with the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

.

* In 1967 awarded the Eugene V. Debs Award

* In 1967 awarded the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 19 ...

that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations.

* Named Humanist of the Year in 1970 by the American Humanist Association.

* Named to the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame in January 2014.

Legacy

Randolph had a significant impact on the Civil Rights Movement from the 1930s onward. TheMontgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States ...

in Alabama was directed by E.D. Nixon, who had been a member of the BSCP and was influenced by Randolph's methods of nonviolent confrontation. Nationwide, the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s used tactics pioneered by Randolph, such as encouraging African Americans to vote as a bloc, mass voter registration

In electoral systems, voter registration (or enrollment) is the requirement that a person otherwise eligible to vote must register (or enroll) on an electoral roll, which is usually a prerequisite for being entitled or permitted to vote.

The r ...

, and training activists for nonviolent direct action.

In buildings, streets, and trains

*

* Amtrak

The National Railroad Passenger Corporation, doing business as Amtrak () , is the national passenger railroad company of the United States. It operates inter-city rail service in 46 of the 48 contiguous U.S. States and nine cities in Canada ...

named one of their best sleeping cars, Superliner II Deluxe Sleeper 32503, the "A. Philip Randolph" in his honor.

* A. Philip Randolph Academies of Technology, in Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

, is named in his honor.

* A. Philip Randolph Boulevard in Jacksonville, Florida, formerly named Florida Avenue, was renamed in 1995 in A. Philip Randolph's honor. It is located on Jacksonville's east side, near TIAA Bank Field

TIAA Bank Field is an American football stadium located in Jacksonville, Florida, that primarily serves as the home facility of the Jacksonville Jaguars of the National Football League (NFL) and the headquarters of the professional wrestling prom ...

.

*A. Philip Randolph Heritage Park in Jacksonville, Florida.

* A. Philip Randolph Campus High School (New York City High School 540), located on the City College of New York campus, is named in honor of Randolph. The school serves students predominantly from Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

and surrounding neighborhoods.

* The A. Philip Randolph Career Academy in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

was named in his honor.

* The A. Philip Randolph Career and Technician Center in Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

is named in his honor.

* The A. Philip Randolph Institute is named in his honor.

* PS 76 A. Philip Randolph in New York City is named in his honor

* A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is in Chicago's Pullman Historic District.

* Edward Waters College

Edward Waters University is a private Christian historically Black university in Jacksonville, Florida. It was founded in 1866 by members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME Church) as a school to educate freedmen and their children. ...

in Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

houses a permanent exhibit on the life and accomplishments of A. Philip Randolph.

* Randolph Street, in Crescent City, Florida, was dedicated to him.

* A. Philip Randolph Library, at Borough of Manhattan Community College

The Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) is a public community college in New York City. Founded in 1963 as part of the City University of New York (CUNY) system, BMCC grants associate degrees in a wide variety of vocational, busines ...

* A. Philip Randolph Square park in Central Harlem was renamed to honor A. Philip Randolph in 1964 by the City Council.

Arts, entertainment, and media

* In the 2015 book The Road to Character author David Brooks includes him among the biographical sketches of individuals of good character * In 1994 a PBS documentary ''A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs and Freedom'' * In 2002, scholarMolefi Kete Asante

Molefi Kete Asante ( ; born Arthur Lee Smith Jr.; August 14, 1942) is an American professor and philosopher. He is a leading figure in the fields of African-American studies, African studies, and communication studies. He is currently professo ...

listed A. Philip Randolph on his list of '' 100 Greatest African Americans''.

* The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Founded in 1925, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The BSCP gathered a membership of 18,000 passenger railwa ...

was made into the 2002 Robert Townsend film '' 10,000 Black Men Named George'' starring Andre Braugher

Andre Keith Braugher (; born July 1, 1962) is an American actor. He is best known for his roles as Detective Frank Pembleton in the police drama series '' Homicide: Life on the Street'' (1993–1999), used car salesman Owen Thoreau Jr. in the com ...

as A. Philip Randolph. The title refers to the demeaning custom of the time when Pullman porters, all of whom were black, were just addressed as "George" (short for "George's boys", a reference to Pullman Company founder George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car and founded a company town, Pullman, for the workers who manufactured it. This ulti ...

).

* A statue of A. Philip Randolph was erected in his honor in the concourse of Union Station

A union station (also known as a union terminal, a joint station in Europe, and a joint-use station in Japan) is a railway station at which the tracks and facilities are shared by two or more separate railway companies, allowing passengers to ...

in Washington, D.C..

* In 1986 a five-foot bronze statue on a two-foot pedestal of Randolph by Tina Allen was erected in Boston's Back Bay station.

Other

*James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

, co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

(CORE), cited Randolph as one of his primary influences as a civil rights leader.

* Randolph was inducted into the Labor Hall of Honor in 1989.

See also

*List of civil rights leaders

Civil rights leaders are influential figures in the promotion and implementation of political freedom and the expansion of personal civil liberties and rights. They work to protect individuals and groups from political repressio ...

* Milton P. Webster

Footnotes

Further reading

* Jervis Anderson, ''A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait.'' New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1973. * Thomas R. Brooks and A.H. Raskin, "A. Philip Randolph, 1889–1979", ''The New Leader'', June 4, 1979, pp. 6–9. * Daniel S. Davis, ''Mr. Black Labor: The Story of A. Philip Randolph, Father of the Civil Rights Movement''. New York: Dutton, 1972. * Paul Delaney, "A. Philip Randolph, Rights Leader, Dies: President Leads Tributes", ''New York Times'', May 18, 1979, pg. B4. * Andrew E. Kersten, ''A. Philip Randolph: A Life in the Vanguard.'' Rowman and Littlefield, 2006. * Andrew E. Kersten and Clarence Lang (eds.), ''Reframing Randolph: Labor, Black Freedom, and the Legacies of A. Philip Randolph.'' New York: New York University Press, 2015. * William H. Harris, "A. Philip Randolph as a Charismatic Leader, 1925–1941", ''Journal of Negro History'', vol. 64 (1979), pp. 301–315. * Paul Le Blanc and Michael Yates, ''A Freedom Budget for All Americans: Recapturing the Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in the Struggle for Economic Justice Today''. with Michael D. Yates. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2013. *Manning Marable

William Manning Marable (May 13, 1950 – April 1, 2011) was an American professor of public affairs, history and African-American Studies at Columbia University.Grimes, William"Manning Marable, Historian and Social Critic, Dies at 60" ''The Ne ...

, "A. Philip Randolph and the Foundations of Black American Socialism", ''Radical America'', vol. 14 (March–April 1980), pp. 6–29.

* Paula F. Pfeffer, ''A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement'' (1990; Louisiana State University Press, 1996).

* Cynthia Taylor, ''A. Philip Randolph: The Religious Journey of An African American Labor Leader'' (NYU Press, 2006).

* SUMMERVILLE, RAYMOND M. 2020. “Winning Freedom and Exacting Justice”: A. Philip Randolph's Use of Proverbs and Proverbial Language. '' Proverbium'' 37:281-310

* Sarah E. Wright, ''A. Philip Randolph: Integration in the Workplace'' (Silver Burdett Press, 1990),

External links

*A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum

A. Philp Randolph Institute

The Senior Constituency Group of the *

American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

(AFL-CIO)

AFL-CIO Labor History Biography of Randolph

* * A. Philip Randolph's

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

files, hosted at the Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

*Part 1

*

Part 2

A. Philip Randolph Collected Papers

held by th

Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Documentaries

10,000 Black Men Named George

entry from the

Internet Movie Database

IMDb (an abbreviation of Internet Movie Database) is an online database of information related to films, television series, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and personal biographies, ...

A. Philip Randolph Exhibit

at the

George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union leader for 57 years. He was the key figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as the AFL–CIO's first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son ...

Memorial Archives of the National Labor College.

A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs and Freedom

86 minutes, Producer:

WETA-TV

WETA-TV (channel 26) is the primary PBS member television station in Washington, D.C. Owned by the Greater Washington Educational Telecommunications Association, it is a sister station to NPR member WETA (90.9 FM). The two outlets share stud ...

. Director: Dante James. Distributor: California Newsreel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Randolph, A. Philip

1889 births

1979 deaths

20th-century African-American activists

Activists for African-American civil rights

Activists from Florida

Activists from New York (state)

African-American trade unionists

American trade union leaders

American people in rail transportation

City College of New York alumni

Harlem Renaissance

Members of Social Democrats USA

Nonviolence advocates

People from Crescent City, Florida

People from Jacksonville, Florida

Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

Socialist Party of America politicians from New York (state)

Spingarn Medal winners