8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 8th (King's) Regiment of Foot, also referred to in short as the 8th Foot and the King's, was an

For almost a decade, the regiment undertook garrison duties in

For almost a decade, the regiment undertook garrison duties in  The threat of a French-supported Jacobite uprising in Scotland arose in 1708 and the Queen's was among those regiments recalled to Britain. Once the Royal Navy intercepted an invasion fleet off the English coast, the regiment returned to the Low Countries, disembarking at

The threat of a French-supported Jacobite uprising in Scotland arose in 1708 and the Queen's was among those regiments recalled to Britain. Once the Royal Navy intercepted an invasion fleet off the English coast, the regiment returned to the Low Countries, disembarking at

Rebellion against the Hanoverian King George I began in 1715 by Jacobite supporters of James Stuart, "

Rebellion against the Hanoverian King George I began in 1715 by Jacobite supporters of James Stuart, " The King's remained in Scotland until 1717, by which time the Jacobite uprising had been suppressed. The regiment served in Ireland between May 1717 and May 1721 and between winter 1722 and spring 1727. The regiment embarked to

The King's remained in Scotland until 1717, by which time the Jacobite uprising had been suppressed. The regiment served in Ireland between May 1717 and May 1721 and between winter 1722 and spring 1727. The regiment embarked to

In April 1813, two companies of the 8th, elements of the Canadian militia, and Native American allies attempted to repulse an American attack on York (present-day Toronto). As the Americans landed on the shoreline, the grenadier company engaged them in a bayonet charge with 46 killed, including its commanding officer, Captain Neal McNeale. The Americans nevertheless overwhelmed the area but subsequently incurred 250 casualties, notably General

In April 1813, two companies of the 8th, elements of the Canadian militia, and Native American allies attempted to repulse an American attack on York (present-day Toronto). As the Americans landed on the shoreline, the grenadier company engaged them in a bayonet charge with 46 killed, including its commanding officer, Captain Neal McNeale. The Americans nevertheless overwhelmed the area but subsequently incurred 250 casualties, notably General

After a period of seven weeks in Jullundur, the regiment became attached to an army preparing to besiege

After a period of seven weeks in Jullundur, the regiment became attached to an army preparing to besiege

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

, formed in 1685 and retitled the King's (Liverpool Regiment) on 1 July 1881.

As infantry of the line

Line infantry was the type of infantry that composed the basis of European land armies from the late 17th century to the mid-19th century. Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus are generally regarded as its pioneers, while Turenne and Mont ...

, the 8th (King's) peacetime responsibilities included service overseas in garrisons ranging from British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

, the Ionian Islands, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, and the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

. The duration of these deployments varied considerably, sometimes exceeding a decade; its first tour of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

began in 1768 and ended in 1785.

The regiment served in numerous conflicts during its existence, notably in the wars with France that dominated the 18th and 19th centuries, the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, and the Indian rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

(historically referred to as the "Indian Mutiny" by Britain). As a consequence of Childers reforms

The Childers Reforms of 1881 reorganised the infantry regiments of the British Army. The reforms were done by Secretary of State for War Hugh Childers during 1881, and were a continuation of the earlier Cardwell Reforms.

The reorganisation wa ...

, the 8th became the King's (Liverpool Regiment). A pre-existing affiliation with the city had derived from its depot being situated in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

from 1873 because of the earlier Cardwell reforms

The Cardwell Reforms were a series of reforms of the British Army undertaken by Secretary of State for War Edward Cardwell between 1868 and 1874 with the support of Liberal prime minister William Ewart Gladstone. Gladstone paid little attention ...

.

History

The regiment formed as the Princess Anne of Denmark's Regiment of Foot during a rebellion in 1685 by the Duke of Monmouth against King James II. After James was deposed during the "Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

" that installed William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife A ...

as co-monarchs, the regiment's commanding officer, the Duke of Berwick, decided to join his royal father in exile.Mileham (2000), pp. 2-3 His replacement as commanding officer was Colonel John Beaumont, who had earlier been dismissed with six officers for refusing to accept a draft of Catholics.

It took part in the Siege of Carrickfergus

The siege of Carrickfergus took place in August 1689 when a force of Williamite troops under Marshal Schomberg landed and laid siege to the Jacobite garrison of Carrickfergus in Ireland. After a week the Jacobites surrendered, and were allow ...

in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

in 1689 and in the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ga, Cath na Bóinne ) was a battle in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II of England and Ireland, VII of Scotland, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and J ...

the following year.Cannon (1844), p. 18 Further actions, while under the command of John Churchill (later 1st Duke of Marlborough) took place that year involving the regiment during the sieges of Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2 ...

, Cork and Kinsale.

War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714)

For almost a decade, the regiment undertook garrison duties in

For almost a decade, the regiment undertook garrison duties in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, and the Dutch United Provinces, where it paraded for King William on Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

Heath in September 1701. On the accession of Princess Anne

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950), is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of ...

to the throne in 1702, the regiment became the Queen's Regiment of Foot, although it continued to be referred to as Webb's

Webb's a.k.a. H. S. Webb, was a department store based in Glendale, California, the first in that city. Origins

The store was founded by Harry S. Webb (d. 1947) in 1917 in Downtown Glendale in a single room. It had locations in the Glendale Fashio ...

Regiment per an unofficial army convention that had a unit known by the name of its colonel.Mileham (2004), p. 4 The War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, predicated on a dispute between a " Grand Alliance" and France over who would succeed Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War ...

, reached the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

in April 1702. While Dutch marshal Prince Walrad took the initiative and besieged Kaiserswerth

Kaiserswerth is one of the oldest quarters of the City of Düsseldorf, part of Borough 5. It is in the north of the city and next to the river Rhine. It houses the where Florence Nightingale worked.

Kaiserswerth has an area of , and 7,923 inh ...

, the French Marshal duc de Boufflers forced Walrad's colleague, the Earl of Athlone

The title of Earl of Athlone has been created three times.

History

It was created first in the Peerage of Ireland in 1692 by King William III for General Baron van Reede, Lord of Ginkel, a Dutch nobleman, to honour him for his successful ...

, to withdraw deep into the Dutch Republic. Supporting Athlone's army, the Queen's Regiment fought near Nijmegen

Nijmegen (;; Spanish and it, Nimega. Nijmeegs: ''Nimwèège'' ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and tenth largest of the Netherlands as a whole, located on the Waal river close to the German border. It is about 6 ...

in a rearguard action during the Dutch Army's retreat between the Maas and Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

rivers. John Churchill, Earl (later Duke) of Marlborough, ranked as Captain-General with limited authority over Dutch forces, arrived in the Low Countries soon afterwards to assume control of a multi-national army organised by the Grand Alliance. He invaded the French-controlled Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands ( Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the ...

and presided over a series of sieges at Venlo

Venlo () is a city and municipality in the southeastern Netherlands, close to the border with Germany. It is situated in the province of Limburg, about 50 km east of the city of Eindhoven, 65 km north east of the provincial capital Maastricht, a ...

, Roermond

Roermond (; li, Remunj or ) is a city, municipality, and diocese in the Limburg province of the Netherlands. Roermond is a historically important town on the lower Roer on the east bank of the river Meuse. It received town rights in 1231. Ro ...

, Stevensweert

Stevensweert is a village in the Dutch province of Limburg. It is located in the municipality of Maasgouw. It lies on the right bank of the river Meuse, which forms the border with Kessenich in Belgium. There was also a ferry to this village.

...

, and Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far fro ...

, in which the regiment's grenadier company breached the citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

. After a lull during the winter, Marlborough struggled to retain the cohesion of his army against the inclination of Dutch generals to divide his resources, while the army itself experienced a reverse at Liège in 1703.Mileham (2000), p. 5

Later in the year, the regiment assisted in the capture of Huy

Huy ( or ; nl, Hoei, ; wa, Hu) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium. Huy lies along the river Meuse, at the mouth of the small river Hoyoux. It is in the ''sillon industriel'', the former industrial ...

and Limbourg, but the campaigns in 1702 and 1703 nevertheless "were largely indecisive".Hoppit (2002), p. 116 To aid the beleaguered Austrian Habsburgs The term Habsburg Austria may refer to the lands ruled by the Austrian branch of the Habsburgs, or the historical Austria. Depending on the context, it may be defined as:

* The Duchy of Austria, after 1453 the Archduchy of Austria

* The '' Erblande' ...

and preserve the alliance, Marlborough sought to engage the French in a definitive set-piece battle in 1704 by advancing into Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, an ally of France, and combining his force with that of Prince Eugene. As an army of 40,000 men assembled, Marlborough's elaborate programme of deception concealed his intentions from the French. The army invaded Bavaria on 2 July and promptly captured the Schellenberg after a devastating assault that included a contingent from the Queen's.Mileham (2000), p. 6 On 13 August, the Allies encountered a Franco-Bavarian army under the overall command of the duc de Tallard, beginning the Battle of Blenheim

The Battle of Blenheim (german: Zweite Schlacht bei Höchstädt, link=no; french: Bataille de Höchstädt, link=no; nl, Slag bij Blenheim, link=no) fought on , was a major battle of the War of the Spanish Succession. The overwhelming Allied ...

. The Queen's Regiment, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Sutton, supported General Lord Cutts' left wing, opposite to French-held Blenheim Blenheim ( ) is the English name of Blindheim, a village in Bavaria, Germany, which was the site of the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. Almost all places and other things called Blenheim are named directly or indirectly in honour of the battle.

Places ...

. According to a contemporary account by Francis Hare, Chaplain-General of Marlborough's army, the Queen's secured a French-constructed "barrier" to prevent it being used as a route of escape, taking hundreds prisoner in its vicinity. Blenheim had become congested with French soldiers and its streets filled with dead and wounded. About 13,000 French soldiers eventually surrendered, including Tallard, while the collective carnage caused more than 30,000 soldiers to become casualties.Black (1998), p. 50

The effective collapse of Bavaria as a French ally and the capture of its most significant fortresses followed Blenheim by year's end. After a period of recuperation and reinforcement in Nijmegen and Breda, the Queen's returned to active service during the Allies' attempted invasion of France, via the Moselle

The Moselle ( , ; german: Mosel ; lb, Musel ) is a river that rises in the Vosges mountains and flows through north-eastern France and Luxembourg to western Germany. It is a left bank tributary of the Rhine, which it joins at Koblenz. A ...

, in May 1705.Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 23 In June, French Marshal Villeroi captured Huy and besieged Liège, forcing Marlborough to abort a campaign that lacked appreciable Allied support.Sundstrom (1991), p. 151 The regiment became detached from Marlborough's army to assist in the retaking of Huy before rejoining for the subsequent attack on the Lines of Brabant Although the lines were overcome, French resistance, combined with opposition among some Dutch generals and adverse weather conditions, prevented much exploitation. The Queen's helped to seize Neerwinden

Neerwinden is a village in Belgium in the province of Flemish Brabant, a few miles southeast of Tienen. It is now part of the municipality of Landen.

The village gave its name to two great battles. The first battle was fought in 1693 between t ...

, Neerhespen, and the bridge at Elixheim.Mileham (2000), p. 7–8

In May 1706, Villeroi, pressured by King Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

to atone for France's earlier defeats, initiated an offensive in the Low Countries by crossing the Dyle river.Chandler (2003), p70–3 Marlborough engaged Villeroi's army near Ramillies on 23 May. Along with 11 battalions and 39 squadrons of cavalry under Lord Orkney, the Queen's fought initially in what transpired to be a feint attack on the left flank of the French lines. The feint convinced Villeroi to divert troops from the centre, while Marlborough had to use representatives to repeatedly instruct Orkney not to continue the attack. Most of Orkney's battalions, including the Queen's, redeployed to support Marlborough on the left. By 19:00, the Franco-Bavarian army had completely disintegrated. For the remainder of 1706, the Allies systematically captured towns and fortresses, including Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

, Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, and Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

. The regiment fought its last siege of 1706 at Menin, one of the most formidably defended fortresses in Europe.

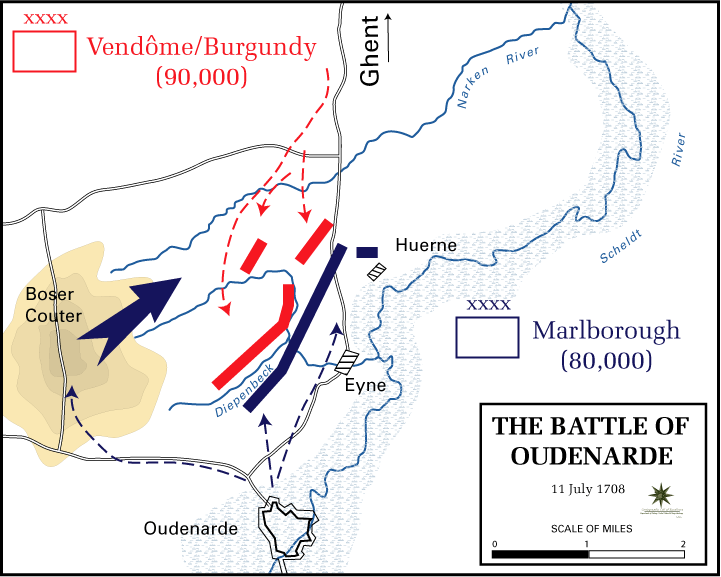

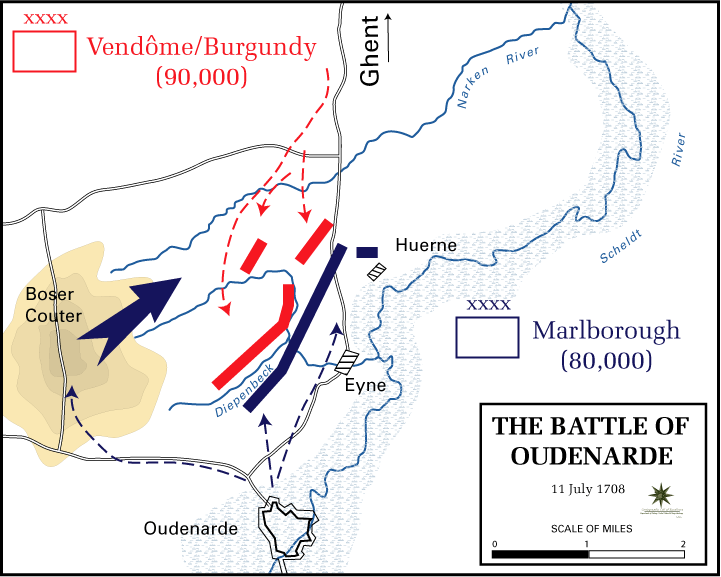

The threat of a French-supported Jacobite uprising in Scotland arose in 1708 and the Queen's was among those regiments recalled to Britain. Once the Royal Navy intercepted an invasion fleet off the English coast, the regiment returned to the Low Countries, disembarking at

The threat of a French-supported Jacobite uprising in Scotland arose in 1708 and the Queen's was among those regiments recalled to Britain. Once the Royal Navy intercepted an invasion fleet off the English coast, the regiment returned to the Low Countries, disembarking at Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

. The French later returned to the offensive, attacking Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

and capturing territory that had been lost in 1706. Marlborough had positioned his forces near Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, anticipating that an offensive might be directed against the city, and had to march his army over a period of two days. On 11 July, Marlborough led an Allied army against Bourgogne

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The ...

, grandson of King Louis, and Marshal Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a subprefecture of the department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the main towns along the river Loir. The river divides itself at the ...

's 100,000–man army at the Battle of Oudenarde

The Battle of Oudenarde, also known as the Battle of Oudenaarde, was a major engagement of the War of the Spanish Succession, pitting a Grand Alliance force consisting of eighty thousand men under the command of the Duke of Marlborough and Prin ...

. The Queen's joined an advanced contingent under Lord Cadogan which crossed the Scheldt

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corresponding to ...

, via pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow- draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load that they can carry ...

s assembled near Oudenarde, as a prelude to the arrival of the main army. While elements of the main army began to arrive at the bridges, Cadogan advanced on the village of Eyne

Eyne (; ca, Eina) is a commune in the Pyrénées-Orientales department in southern France.

Geography Localization

Eyne is located in the canton of Les Pyrénées catalanes and in the arrondissement of Prades

The arrondissement of Prades is ...

and swiftly overwhelmed an isolated group of four Swiss mercenary

The Swiss mercenaries (german: Reisläufer) were a powerful infantry force constituted by professional soldiers originating from the cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. They were notable for their service in foreign armies, especially among th ...

battalions; three surrendered and the fourth attempted to withdraw but was intercepted by Jørgen Rantzau's cavalry. To signify the surrender, the commanding officer of the Queen's received some of their colours

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are associa ...

. The regiment soon became engaged in battle near the village of Herlegem, fighting through the hedges until darkness. Cadogan's precarious situation only began to alleviate by the deployment of the Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll ( gd, Diùc Earraghàidheil) is a title created in the peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The earls, marquesses, and dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerfu ...

's reinforcements.

The Queen's became occupied by a succession of sieges: at Ghent, Bruges, and Lillie.Mileham (2000), p. 9 In 1709, the regiment assisted in the protracted Siege of Tournai

Tournai or Tournay ( ; ; nl, Doornik ; pcd, Tornai; wa, Tornè ; la, Tornacum) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies southwest of Brussels on the river Scheldt. Tournai is part of Eurome ...

, which capitulated in September. On the 11th, the regiment fought in the bloodiest battle of the war: Malplaquet. After being committed from reserve in the battle's closing stages, the regiment advanced under heavy fire and fought through dense wood, having Lieutenant-Colonel Louis de Ramsay killed. The memoirs of Private Matthew Bishop, of the Queen's Regiment, contained an account that recalled: "the French were well prepared to give us a warm salute. It soon broke us in a terrible manner, though our vacancies were quickly filled up...when we got clear of the dead and wounded, we ran upon them and returning their fire, even broke them out of the breast-work."

In 1710, the regiment was represented at the sieges of Douai

Douai (, , ,; pcd, Doï; nl, Dowaai; formerly spelled Douay or Doway in English) is a city in the Nord département in northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department. Located on the river Scarpe some from Lille and from Arras, Dou ...

, Béthune

Béthune ( ; archaic and ''Bethwyn'' historically in English) is a city in northern France, sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department.

Geography

Béthune is located in the former province of Artois. It is situated south-east of Calais, ...

, Aire

Aire may refer to:

Music

* ''Aire'' (Yuri album), 1987

* ''Aire'' (Pablo Ruiz album), 1997

*''Aire (Versión Día)'', an album by Jesse & Joy

Places

*Aire-sur-la-Lys, a town in the Pas-de-Calais département in France

*Aire-la-Ville, a municip ...

and St. Venant.

Jacobites and renewed European conflict (1715–1768)

Rebellion against the Hanoverian King George I began in 1715 by Jacobite supporters of James Stuart, "

Rebellion against the Hanoverian King George I began in 1715 by Jacobite supporters of James Stuart, "Old Pretender

James Francis Edward Stuart (10 June 16881 January 1766), nicknamed the Old Pretender by Whigs, was the son of King James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland, and his second wife, Mary of Modena. He was Prince of Wales from ...

" to the throne of Great Britain. As unrest escalated in Britain, the Queen's Regiment arrived in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and became absorbed by a Government army under the Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll ( gd, Diùc Earraghàidheil) is a title created in the peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The earls, marquesses, and dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerfu ...

.Mileham (2000), p. 11-2 Although numerically superior, the Jacobite army did not begin an advance south until November because of the caution of their leader, the Earl of Mar

There are currently two earldoms of Mar in the Peerage of Scotland, and the title has been created seven times. The first creation of the earldom is currently held by Margaret of Mar, 31st Countess of Mar, who is also clan chief of Clan Mar. T ...

.Szechi (2006), pp. 151-2 The Duke of Argyll moved north from Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

and positioned his forces in the vicinity of Dunblane

Dunblane (, gd, Dùn Bhlàthain) is a small town in the council area of Stirling in central Scotland, and inside the historic boundaries of the county of Perthshire. It is a commuter town, with many residents making use of good transport links ...

on 12 November. On the morning of the 13th, in conditions that had frozen the ground during the night, the Battle of Sheriffmuir began.

The Queen's Regiment formed part of General Thomas Whetham

Thomas Whetham (c. 1665 – 28 April 1741) was an English soldier and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1722 and 1727.

Family and early life

Whetham was born circa 1665, the first son of the barrister Nathaniel Whetham, of the ...

's left wing. Confused troop movements led to both it and the Jacobite left being weaker than the corresponding right wing.Roberts (2002), p. 45 While Whetham's men attempted to readjust their dispositions, a mass of Highlanders began a rapid charge. Entwined in hand-to-hand combat within minutes, the sides fought until Whetham's men broke and retreated in disarray. The Queen's had 111 killed, including Lieutenant-Colonel Hanmer, 14 wounded, and 12 captured. The remnants withdrew from the battlefield until almost upon Stirling. Without cavalry support, the Jacobite left also broke, and the Earl of Mar abandoned the area at nightfall.

In 1716 at the behest of George I, to honour the regiment's service at Sheriffmuir, the Queen's became the King's Regiment of Foot, with the White Horse of Hanover

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

(symbol of the Royal Household) as its badge.

The King's remained in Scotland until 1717, by which time the Jacobite uprising had been suppressed. The regiment served in Ireland between May 1717 and May 1721 and between winter 1722 and spring 1727. The regiment embarked to

The King's remained in Scotland until 1717, by which time the Jacobite uprising had been suppressed. The regiment served in Ireland between May 1717 and May 1721 and between winter 1722 and spring 1727. The regiment embarked to Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

in winter 1742 for service in the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

. It fought at the Battle of Dettingen

The Battle of Dettingen (german: Schlacht bei Dettingen) took place on 27 June 1743 during the War of the Austrian Succession at Dettingen in the Electorate of Mainz, Holy Roman Empire (now Karlstein am Main in Bavaria). It was fought between a ...

in June 1743 where, despite the French enjoying superiority in numbers, Britain and its Allies defeated an army under the duc de Noailles

The title of Duke of Noailles was a French peerage created in 1663 for Anne de Noailles, Count of Ayen.

History

Noailles is the name of a prominent French noble family, derived from the castle of Noailles in the territory of Ayen, between Brive ...

. The regiment also took part in the Battle of Fontenoy

The Battle of Fontenoy was a major engagement of the War of the Austrian Succession, fought on 11 May 1745 near Tournai in modern Belgium. A French army of 50,000 under Marshal Saxe defeated a Pragmatic Army of roughly the same size, led by ...

in May 1745: the King's Regiment was positioned in the frontline of the Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British Royal Family, named after the historic county of Cumberland.

History

The Earldom of Cumberland, created in 1525, became extinct in 1643. The dukedom ...

's army but a retreat was eventually ordered.

In 1745, Prince Charles Edward (popularly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie, is a Scottish given name and is sometimes used as a descriptive reference, as in the Scottish folk song, My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean. It comes from the Scots language word "bonnie" (pretty, attractive), or the French bonne (good). That ...

) landed in Scotland, seeking to restore the Stuarts to the British throne. The regiment did not become committed to battle until the Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice'' in Gaelic), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William Wa ...

in January 1746. The regiment was part of the left wing of the front line of the army, under the command of Lieutenant-General Henry Hawley

Henry Hawley (12 January 1685 – 24 March 1759) was a British army officer who served in the wars of the first half of the 18th century. He fought in a number of significant battles, including the Capture of Vigo in 1719, Dettingen, Fo ...

. After a failed attack by dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s of Hawley's army, the Highlanders loyal to Prince Charles charged the Government forces, compelling the left wing of the army to withdraw while the right wing held. The rebels and Government armies both withdrew from the battlefield by night-time.Cannon (1844), p. 57 The regiment also fought in the Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden (; gd, Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the Jacobite rising of 1745. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite army of Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force under Prince Wi ...

in April 1746. Once the impetuous Highlanders charged and overcame the initial volley of fire, vicious hand-to-hand fighting ensued with Hawley's men. The King's provided cross-fire support, firing across the front-line and into the Highlanders. The regiment sustained a single, severely wounded casualty.

The King's fought in the Battle of Rocoux

The Battle of Rocoux took place on 11 October 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession, at Rocourt (or Rocoux), near Liège in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, now modern Belgium. It was fought between a French army under Marshal Saxe a ...

in October 1746Cannon (1844), p. 58 and the Battle of Lauffeld

The Battle of Lauffeld, variously known as Lafelt, Laffeld, Lawfeld, Lawfeldt, Maastricht, or Val, took place on 2 July 1747, between Tongeren in modern Belgium, and the Dutch city of Maastricht. Part of the War of the Austrian Succession, a Fr ...

in July 1747. In the latter, the King's and three other regiments became embroiled in a protracted struggle through the avenues of Val

Val may refer to: Val-a

Film

* ''Val'' (film), an American documentary about Val Kilmer, directed by Leo Scott and Ting Poo

Military equipment

* Aichi D3A, a Japanese World War II dive bomber codenamed "Val" by the Allies

* AS Val, a Sov ...

. Control of the village fluctuated throughout the battle until the Allies retreated before overwhelming numbers.Cannon (1844), p. 60

The British Army implemented a numbering system in 1751 to reflect the seniority of a regiment by its date of creation, with the King's becoming the 8th (King's) Regiment of Foot in the order of precedence

An order of precedence is a sequential hierarchy of nominal importance and can be applied to individuals, groups, or organizations. Most often it is used in the context of people by many organizations and governments, for very formal and state o ...

. The beginning of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, which would encompass Europe and its colonial possessions, necessitated the 8th's expansion to two battalions, amounting to a total of 20 companies.Mileham (2000), p. 15 Both battalions formed part of an expedition in 1757 that captured Île d'Aix, an island off the western coast of France, as a precursor to a planned seizure of the mainland garrison town of Rochefort

Rochefort () may refer to:

Places France

* Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, in the Charente-Maritime department

** Arsenal de Rochefort, a former naval base and dockyard

* Rochefort, Savoie in the Savoie department

* Rochefort-du-Gard, in the Ga ...

. The 2nd Battalion became the 63rd Regiment of Foot

The 63rd Regiment of Foot was a British Army regiment raised in 1756. Under the Childers Reforms, it amalgamated with the 96th Regiment of Foot to form the Manchester Regiment in 1881.

History Formation and service in the Seven Years' War

The fo ...

in 1758.

When the regiment augmented the Hanoverian Army in 1760, the 8th King's had its grenadier

A grenadier ( , ; derived from the word ''grenade'') was originally a specialist soldier who threw hand grenades in battle. The distinct combat function of the grenadier was established in the mid-17th century, when grenadiers were recruited from ...

company committed to the battles of Warburg

Warburg (; Westphalian: ''Warberich'' or ''Warborg'') is a town in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, central Germany on the river Diemel near the three-state point shared by Hessen, Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia. It is in Höxter di ...

and Kloster Kampen. As a complete regiment, the 8th served at Kirch-Denkern, Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

, Wilhelmsthal

Wilhelmsthal is a municipality in the district of Kronach in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the large ...

, and the capture of Cassel.

American Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

The 8th Foot arrived inCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

in 1768 and had its ten companies dispersed to garrison isolated posts on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

: Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great Lakes. The fort is on the river's e ...

(four), Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Detroit (1701–1796) was a fort established on the north bank of the Detroit River by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and the Italian Alphonse de Tonty in 1701. In the 18th century, Fre ...

(three), Fort Michilimackinac

Fort Michilimackinac was an 18th-century French, and later British, fort and trading post at the Straits of Mackinac; it was built on the northern tip of the lower peninsula of the present-day state of Michigan in the United States. Built aroun ...

(two), and Fort Oswego

Fort Oswego was an 18th-century trading post in the Great Lakes region in North America, which became the site of a battle between French and British forces in 1756 during the French and Indian War. The fort was established in 1727 on the orders o ...

(one). As the regiment's deployment appeared to near completion, protests in the eastern colonies began to intensify, evolving from vocal concerns about self-determination and taxation without representation, to rebellion against Britain in 1775.

During its posting, the 8th Foot possessed a number of officers adept in cultivating a relationship with tribes on the Great Lakes, notable amongst them being Captain Arent DePeyster

Arent Schuyler DePeyster (27 June 1736 – 26 November 1822) was an American-born military officer best known for his term as commandant of the British controlled Fort Michilimackinac and Fort Detroit during the American Revolution. Following t ...

and Lieutenant John Caldwell. Later to become 5th Baronet of County Fermanagh

County Fermanagh ( ; ) is one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the six counties of Northern Ireland.

The county covers an area of 1,691 km2 (653 sq mi) and has a population of 61,805 ...

's Caldwell Castle, Caldwell immersed himself in his efforts to foster understanding between the British and Ojibwa, reputedly marrying a member of the tribe and becoming a chief under the adopted name of "The Runner".Mileham (2000), p. 21 In the west, Captain DePeyster's negotiations proved instrumental in maintaining peace between the British and tribes such as the Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

* Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

* Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been ...

and Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

nations. Born into a prominent New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

family of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

origin, DePeyster held authority over Fort Michilimackinac. In 1778, using £19,000 of goods as leverage, he arranged for more than 550 warriors from several tribes to serve in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

and Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

.

The invasion of Canada by American generals Richard Montgomery

Richard Montgomery (2 December 1738 – 31 December 1775) was an Irish soldier who first served in the British Army. He later became a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and he is most famous for l ...

and Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

began in mid-1775. By the end of November, the Americans had captured Fort St. Jean, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, and Fort Chambly

Fort Chambly is a historic fort in La Vallée-du-Richelieu Regional County Municipality, Quebec. It is designated as a National Historic Site of Canada. Fort Chambly was formerly known as Fort St. Louis. It was part of a series of five fortificat ...

, and besieged the city of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

. An attempt to storm it in December resulted in Montgomery's death. Reinforcements from Europe raised the siege in May 1776 and expelled the almost starved and exhausted Americans from the area. After the lifting of the siege, a small party from the 8th Foot led the regiment to its first significant battle in the war.

From Fort Oswegatchie

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

, Captain George Forster, of the regiment's light company, led a composite force, including 40 regulars and about 200 warriors, across the St. Lawrence River to attack Fort Cedars, held by 400 Americans under Timothy Bedel.Morrissey & Hook (2003), pp. 66-8 Forster maintained illicit contact with occupied Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, and received intelligence of American troop movements using Indian operatives and Major de Lorimier. On arriving at the fort on 18 May, the British briefly exchanged fire before Forster parleyed with Bedel's successor, Major Isaac Butterfield, to request his surrender and warn him of the consequences should Indian warriors be committed to battle.Nester (2004), p. 106 Butterfield, whose men had apparently been disconcerted by an earlier display of Indian war chanting, expressed a willingness to do so on the proviso of being allowed to retire with his weapons – a condition that Forster refused.

Butterfield conceded the fort on the 19th, on the day an American relief force of about 150 resumed its advance on the Cedars, having previously reembarked aboard bateaux because of exaggerated scout reports. Once he learned of the column's presence, Forster had a detachment ambush the Americans from positions astride the only available path through the forest. The relief's commander, Major Sherburne, surrendered, but the engagement infuriated the Indian contingent as the Allies' only fatality was a Seneca war chief. Forster managed to dissuade them from executing the prisoners by paying substantial ransoms for some of the captives as compensation for the loss.

Emboldened by the two victories, the British landed at Pointe-Claire

Pointe-Claire (, ) is a Quebec local municipality within the Urban agglomeration of Montreal on the Island of Montreal in Canada. It is entirely developed, and land use includes residential, light manufacturing, and retail. As of the 2021 cen ...

, on the Island of Montreal

The Island of Montreal (french: Île de Montréal) is a large island in southwestern Quebec, Canada, that is the site of a number of municipalities including most of the city of Montreal and is the most populous island in Canada. It is the main ...

, only to withdraw after Forster established the strength of General Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

's force at Lachine. In pursuit of a dwindling column, Arnold followed the British using bateaux, but was deterred from landing by Forster's placement of men along the embankment at Quinze-Chênes, supported by two captured cannon pieces. On the 27th, Forster sent Sherburne under a flag of truce to inform Arnold that terms to a prisoner exchange favourable to the British had been agreed upon. Arnold accepted the conditions, with the exception of Americans being forbidden from serving elsewhere. Both Arnold and Forster had postured during the battle, each threatening the other with the prospect of atrocities: the killing of prisoners by Forster's Indian allies and the destruction of Indian villages by Arnold's men. The exchange would be denounced by the American Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

and the arrangement reneged upon under the pretext that abuses had been committed by Forster's men.

In late July 1777, the regiment contributed Captain Richard Leroult and 100 men to the Siege of Fort Stanwix Fort Stanwix was a colonial fort whose construction commenced on August 26, 1758, under the direction of British General John Stanwix, at the location of present-day Rome, New York, but was not completed until about 1762. The bastion fort was built ...

. Commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Barry St. Leger

Barrimore Matthew "Barry" St. Leger (bapt. 1 May 1733 – 23 December 1793) was a British Army officer. St. Leger was active in the Saratoga Campaign, commanding an invasion force that unsuccessfully besieged Fort Stanwix. St. Leger remaine ...

, 34th Foot

The 34th Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1702. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 55th (Westmorland) Regiment of Foot to form the Border Regiment in 1881.

History Early history

The regi ...

, the force ambushed the American troops at the Battle of Oriskany

The Battle of Oriskany ( or ) was a significant engagement of the Saratoga campaign of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the bloodiest battles in the conflict between the Americans and Great Britain. On August 6, 1777, a party of Loya ...

in August 1777: however a few weeks later the siege collapsed with the disappearance of the dis-spirited native allies.

The regiment took part in further actions at Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

and the Battle of Newtown

The Battle of Newtown (August 29, 1779) was a major battle of the Sullivan Expedition, an armed offensive led by General John Sullivan that was ordered by the Continental Congress to end the threat of the Iroquois who had sided with the British ...

(Elmira, New York

Elmira () is a city and the county seat of Chemung County, New York, United States. It is the principal city of the Elmira, New York, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses Chemung County. The population was 26,523 at the 2020 censu ...

) in 1779, as well as the Mohawk Valley

The Mohawk Valley region of the U.S. state of New York is the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack Mountains and Catskill Mountains, northwest of the Capital District. As of the 2010 United States Census, ...

in 1780 and Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

in 1782. Captain Henry Bird of the 8th Regiment led a British and Native American siege of Fort Laurens in 1779. In 1780, he led an invasion of Kentucky, capturing two "stations" (fortified settlements) and returning to Detroit with 300 prisoners. The regiment returned to England in September 1785.Cannon (1844), p. 72

French Revolutionary War

In 1793, revolutionary France declared war on Great Britain. The King's became assigned to an expeditionary force sent to theNetherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

under the command of Prince Frederick, Duke of York

Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (Frederick Augustus; 16 August 1763 – 5 January 1827) was the second son of George III, King of the United Kingdom and Hanover, and his consort Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. A soldier by profess ...

. In 1794, the regiment attempted to lift the French Siege of Nijmegen

Nijmegen (;; Spanish and it, Nimega. Nijmeegs: ''Nimwèège'' ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and tenth largest of the Netherlands as a whole, located on the Waal river close to the German border. It is about 6 ...

. The allies planned a nocturnal attack, with the march conducted without audible commotion. The force leapt into the French earthworks, with hand-to-hand fighting ensuing. Despite the success, the town of Nijmegen was soon evacuated and the British withdrew from the Netherlands in 1795.

In 1799, the King's became resident on Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its cap ...

, which had been captured from Spain the previous year. In 1801, the regiment landed at Abukir Bay, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, with an expedition sent under the command of General Ralph Abercromby

Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby (7 October 173428 March 1801) was a British soldier and politician. He rose to the rank of lieutenant-general in the British Army, was appointed Governor of Trinidad, served as Commander-in-Chief, Ir ...

to counter a French invasion. The King's participated in the capture of Rosetta

Rosetta or Rashid (; ar, رشيد ' ; french: Rosette ; cop, ϯⲣⲁϣⲓⲧ ''ti-Rashit'', Ancient Greek: Βολβιτίνη ''Bolbitinē'') is a port city of the Nile Delta, east of Alexandria, in Egypt's Beheira governorate. The R ...

, 65 miles west of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, and a fort located in Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

.Cannon (1844), p. 78 The British completed the occupation of Egypt by September.

Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812

The regiment was sent toGibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

in 1802 and returned to England in 1803. It landed at Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is an independent town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven ...

in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

in October 1805 as part of the Hanover Expedition

The Hanover Expedition, also known as the Weser Expedition, was a British invasion of the Electorate of Hanover during the Napoleonic Wars. Coordinated as part of an attack on France by the nations of the Third Coalition against Napoleon by W ...

, but was withdrawn in February 1806 before taking part in the Battle of Copenhagen in August 1807.Cannon (1844), p. 81

The 1st Battalion moved to Canada in 1808 as the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

extended to the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

. Within a year, in January 1809, the battalion had embarked at Barbados with an expeditionary force comprising two divisions assembled to invade Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

. Although a number of engagements with the French garrison preceded the island's seizure, disease represented the principal threat to Britain's five-year occupation. By October 1809, some 1,700 of more than 2,000 casualties had succumbed to disease. The 8th Foot returned to Nova Scotia in April, having had its commanding officer, Major Bryce Maxwell, and four others killed in a skirmish with French soldiers on the Surirey Heights during the advance on Fort Desaix

Fort Desaix is a Vauban fort and one of four forts that protect Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique. The fort was built from 1768 to 1772 and sits on a hill, Morne Garnier, overlooking what was then Fort Royal. Fort Desaix was built in r ...

in February.Mileham (2000), p. 36. When sustained tension between the United States and Britain culminated in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, the 1st and 2nd battalions were based in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

respectively.

Sporadic raids into Canada on the eastern frontier provided impetus for a former regimental officer, Lieutenant-Colonel "Red" George MacDonnell, to encroach into New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. sta ...

and attack Ogdensburg in February 1813. To reach their destination, the 8th Foot and Canadian militia had to traverse across the frozen St. Lawrence River and through dense snow.Mileham (2000), p. 37. After gaining control of the fort following close-quarters battle, the British destroyed the main barracks and three anchored vessels, and departed with provisions and prisoners. Ogdensburg would not be reestablished as a frontier garrison, ensuring relative peace in the region.

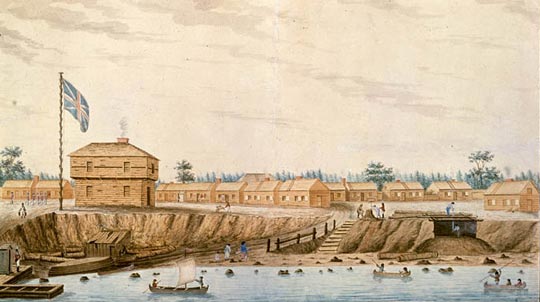

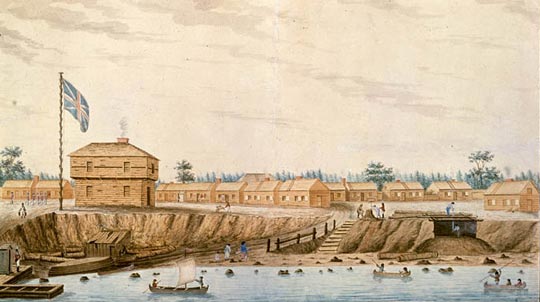

In April 1813, two companies of the 8th, elements of the Canadian militia, and Native American allies attempted to repulse an American attack on York (present-day Toronto). As the Americans landed on the shoreline, the grenadier company engaged them in a bayonet charge with 46 killed, including its commanding officer, Captain Neal McNeale. The Americans nevertheless overwhelmed the area but subsequently incurred 250 casualties, notably General

In April 1813, two companies of the 8th, elements of the Canadian militia, and Native American allies attempted to repulse an American attack on York (present-day Toronto). As the Americans landed on the shoreline, the grenadier company engaged them in a bayonet charge with 46 killed, including its commanding officer, Captain Neal McNeale. The Americans nevertheless overwhelmed the area but subsequently incurred 250 casualties, notably General Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

, when retreating British regulars detonated Fort York's Grand Magazine.

While garrisoning Fort George, at Newark (present day Niagara-on-the-Lake

Niagara-on-the-Lake is a town in Ontario, Canada. It is located on the Niagara Peninsula at the point where the Niagara River meets Lake Ontario, across the river from New York, United States. Niagara-on-the-Lake is in the Niagara Region of O ...

), in May 1813 with companies of the Glengarries and Runchey's Company of Coloured Men, the 8th Foot attempted to disrupt an amphibious landing by the Americans. Although numerically inferior, the British delayed the invasion and retreated without disorder. In June 1813, the 8th and 49th regiments assaulted an American encampment at Stoney Creek. Five companies from the two British regiments engaged more than 4,000 Americans in a nocturnal battle. Although the Americans had two brigadiers captured and suffered losses, the British commander, Colonel John Harvey John Harvey may refer to:

People Academics

* John Harvey (astrologer) (1564–1592), English astrologer and physician

* John Harvey (architectural historian) (1911–1997), British architectural historian, who wrote on English Gothic architecture ...

, considered the possibility of his opponents realising their numerical advantage too compelling to ignore and withdrew.

In July 1814 the regiment fought in the Battle of Chippawa

The Battle of Chippawa, also known as the Battle of Chippewa, was a victory for the United States Army in the War of 1812, during its invasion on July 5, 1814, of the British Empire's colony of Upper Canada along the Niagara River. This battle ...

in which the British commander General Phineas Riall

General Sir Phineas Riall, KCH (15 December 1775 – 10 November 1850) was the British general who succeeded John Vincent as commanding officer of the Niagara Peninsula in Upper Canada during the War of 1812. In 1816, he was appointed Governor ...

retreated after he misidentified American regulars for militia. Later in the month, the regiment fought in the Battle of Lundy's Lane

The Battle of Lundy's Lane, also known as the Battle of Niagara, was a battle fought on 25 July 1814, during the War of 1812, between an invading American army and a British and Canadian army near present-day Niagara Falls, Ontario. It was one o ...

. The British, Canadian and Native soldiers, under the command of Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond

General Sir Gordon Drummond, GCB (27 September 1772 – 10 October 1854) was a Canadian-born British Army officer and the first official to command the military and the civil government of Canada. As Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, Dru ...

, engaged the American force. It was one of the bloodiest battles recorded on Canadian territory. The following month, the King's took part in the action at Snake Hill

Snake Hill (known officially as Laurel Hill) is an igneous rock intrusion jutting up from the floor of the Meadowlands in southern Secaucus, New Jersey, at a bend in the Hackensack River., Variant name: Snake Hill It was largely obliterated in t ...

during the siege of Fort Erie

Fort Erie is a town on the Niagara River in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. It is directly across the river from Buffalo, New York, and is the site of Old Fort Erie which played a prominent role in the War of 1812.

Fort Erie is one of Ni ...

.Cannon (1844), p. 99 In September 1814 the Americans attacked the British posts with overwhelming force and the regiment suffered heavy losses. The King's Regiment received the battle honour 'Niagara' for its contributions to the war.Cannon (1844), p. 100 The regiment landed back in England in summer 1815.

Indian rebellion and Second Afghan War

Between the end of the war and theIndian rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

, the King's undertook a variety of duties in Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It ...

, Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

, Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and Zante

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; el, Ζάκυνθος, Zákynthos ; it, Zacinto ) or Zante (, , ; el, Τζάντε, Tzánte ; from the Venetian form) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands. Za ...

. In 1846, the regiment began a 14-year posting to India, stationed initially in the Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency or Bombay Province, also called Bombay and Sind (1843–1936), was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India, with its capital in the city that came up over the seven islands of Bombay. The first mainl ...

. At the beginning of the rebellion in May 1857, the 8th Foot occupied a cantonment

A cantonment (, , or ) is a military quarters. In Bangladesh, India and other parts of South Asia, a ''cantonment'' refers to a permanent military station (a term from the British India, colonial-era). In military of the United States, United Stat ...

in Jullundur

Jalandhar is the third most-populous city in the Indian state of Punjab and the largest city in Doaba region. Jalandhar lies alongside the Grand Trunk Road and is a well-connected rail and road junction. Jalandhar is northwest of the state ...

, together with three Indian regiments and two troops of horse artillery.

The complex array of motives and causes that culminated in the mutiny of much of the Bengal Army would be catalysed in 1857 by rumours that beef and pork fat was being used to grease paper rifle cartridges. Confined first to a number of Bengal regiments, the mutiny eventually manifested in some areas as a more diverse, albeit disparate, rebellion against British rule.Mileham (2000), p. 49 Soon after reports were received of the first mutiny at Meerut

Meerut (, IAST: ''Meraṭh'') is a city in Meerut district of the western part of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The city lies northeast of the national capital New Delhi, within the National Capital Region and west of the state capital ...

on 10 May, the 8th's commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Hartley, had two companies secure the fort of Phillaur

Phillaur is a city and a municipal council as well as a tehsil in Jalandhar district in the Indian state of Punjab.

Overview

Phillaur is the railway junction on the border line of Ludhiana Main and Ludhiana Cantonment (older spelling: Ludhi ...

, near Jullundur, due to the significance of its magazine stores and reports that the 3rd Bengal Native Infantry intended to seize it.

After a period of seven weeks in Jullundur, the regiment became attached to an army preparing to besiege

After a period of seven weeks in Jullundur, the regiment became attached to an army preparing to besiege Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

. Because of a shortage of troops, due primarily to cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

and other diseases, several weeks elapsed before the British had attained a strength sufficient to commence operations.

In July 1857, two companies supported a position that had been under attack for seven hours. The King's participated in the capture of Ludlow Castle, in the vicinity of Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

Gate in the northern walls of Delhi. Grouped into the 2nd Column with the 2nd Bengal Fusiliers and 4th Sikhs, the 8th King's attacked Delhi early on 14 September with the intent of capturing the Water Bastion and Kashmiri Gate. Once the city had been secured by the British, the 8th's Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Greathed

General Sir Edward Harris Greathed KCB (8 June 1812 – 19 November 1881) was a British Army officer who became General Officer Commanding Eastern District.

Military career

He was born in London, one of the five sons of Edward Harris and Mary ...

vacated his position and became commander of a column dispatched to Cawnpore

Kanpur or Cawnpore ( /kɑːnˈpʊər/ pronunciation (help·info)) is an industrial city in the central-western part of the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Founded in 1207, Kanpur became one of the most important commercial and military stations ...

. The regiment, commanded by Major Hinde, had been seriously depleted and the combined total of it and the 75th Foot numbered just 450. The regiment also took part in the second Relief of Lucknow in November, seeing much action until withdrawing, after the evacuation of civilians, on the 22nd. In an environment of systematic reprisal by the British, Captain Octavius Anson, of the 9th Lancers

The 9th Queen's Royal Lancers was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, first raised in 1715. It saw service for three centuries, including the First and Second World Wars. The regiment survived the immediate post-war reduction in forces, but w ...

, recalled observing acts of punitive violence against Indian civilians, including the alleged killing of incapacitated villagers by soldiers of the 8th Foot.

The 1st Battalion was brought back to Britain in 1860. It spent the year 1865 in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, Ireland, where the battalion supported garrison operations against Irish Republican activity in the city.Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), pp. 155-6 Then, after two years in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, the 1st King's returned to India in 1868. where it remained for a decade.Mileham (2000), pp. 56-7 The regiment's 2nd Battalion, which had been reconstituted in 1857, was itself posted to Malta (in 1863) and India (in 1877), and met up with the 1st King's on the island and at Mundra

Mundra is a census town and a headquarter of Mundra Taluka of Kutch district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Founded in about the 1640s, the town was an important mercantile centre and port throughout its history. Mundra Port is the largest ...

, in the Bombay Presidency.