46th Infantry Division (United Kingdom) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 46th Infantry Division was a

On 10 May 1940, the

On 10 May 1940, the

After returning to the United Kingdom, the division moved to

After returning to the United Kingdom, the division moved to

The division embarked and sailed from Africa on 7 September, assigned to the British X Corps, part of the US Fifth Army. The division was to land near

The division embarked and sailed from Africa on 7 September, assigned to the British X Corps, part of the US Fifth Army. The division was to land near

On 22 September, the division advanced north, and captured several villages and hills after overcoming German resistance. This helped clear the way for the 7th Armoured Division to be employed. They began their advance on 28 September and entered Naples on 1 October. During September, drafts were brought in to replace the 46th Division's casualties. Some of these drafts mutinied, in what became known as the Salerno mutiny, because they were not being reassigned to their former units.

In October, the division attacked the German

On 22 September, the division advanced north, and captured several villages and hills after overcoming German resistance. This helped clear the way for the 7th Armoured Division to be employed. They began their advance on 28 September and entered Naples on 1 October. During September, drafts were brought in to replace the 46th Division's casualties. Some of these drafts mutinied, in what became known as the Salerno mutiny, because they were not being reassigned to their former units.

In October, the division attacked the German

The division left Palestine on 17 June 1944 and returned to Egypt to board ships for Italy. The division landed in Italy on 3 July and was assigned to the V Corps of the British Eighth Army. It then took up position near

The division left Palestine on 17 June 1944 and returned to Egypt to board ships for Italy. The division landed in Italy on 3 July and was assigned to the V Corps of the British Eighth Army. It then took up position near  On 6 November 1944, Major-General

On 6 November 1944, Major-General

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

formed during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

that fought during the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

, the Tunisian Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. Th ...

, and the Italian Campaign. In March 1939, after Germany re-emerged as a significant military power and occupied Czechoslovakia, the British Army increased the number of divisions in the Territorial Army (TA) by duplicating existing units. The 46th Infantry Division was formed in October 1939, as a second-line duplicate of the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division. The division's battalions were drawn largely from men living in the English North Midlands.

It was intended that the division would remain in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

to complete training and preparation, before being deployed to France within twelve months of war breaking out. However, in April 1940, the division was sent to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, leaving behind most of its administration, logistical units, heavy weapons, and artillery. The men were assigned to labouring duties. Following the German invasion of France, the division, only partly trained and ill-equipped, was ordered to the frontline. It was mauled in a series of engagements, before it was evacuated from France during the Dunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allies of World War II, Allied soldiers during the World War II, Second World War from the bea ...

and in the subsequent evacuation codenamed Operation Aerial

Operation Aerial was the evacuation of Allied forces and civilians from ports in western France from 15 to 25 June 1940 during the Second World War. The evacuation followed the Allied military collapse in the Battle of France against Nazi Germ ...

. Back in the United Kingdom, the division was rebuilt and trained extensively.

In December 1942, it departed for North Africa and fought in the campaign in Tunisia. In 1943, it landed at Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

and fought in Italy through 1943 and into 1944. The division was then given a three-month respite in Africa and the Middle East before it returned to fight in Italy during the campaign to break through the Gothic Line

The Gothic Line (german: Gotenstellung; it, Linea Gotica) was a German defensive line of the Italian Campaign of World War II. It formed Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's last major line of defence along the summits of the northern part of ...

. At the end of 1944, the division was dispatched to Greece after the second stage of the country's civil war broke out. It fought several skirmishes with communist partisans and assisted the Greek Government in restoring order. In 1945, the division returned to Italy just after the Spring 1945 offensive in Italy

The spring 1945 offensive in Italy, codenamed Operation Grapeshot, was the final Allied attack during the Italian Campaign in the final stages of the Second World War. The attack into the Lombard Plain by the 15th Allied Army Group started on ...

began. The division did not arrive at the forward area until after the campaign, and the war in Europe had ended. It then marched into Austria to form part of the occupation force. There, the division took part in Operation Keelhaul

Operation Keelhaul was a forced repatriation of Russian civilians (non-Soviet citizens) and Soviet citizens to the Soviet Union. While forced repatriation focused on Soviet Armed Forces POWs of Germany and Russian Liberation Army members, it incl ...

, which included the forced repatriation of Cossacks to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, some of whom were later executed. The division was disbanded in Austria in 1947 as part of Britain's post-war demobilisation.

Background

During the 1930s, tensions increased betweenGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and the United Kingdom and its allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. In late 1937 and throughout 1938, German demands for the annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

led to an international crisis. To avoid war, the British prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

met with German chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

in September and brokered the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

. It averted a war and allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland. Although Chamberlain had intended the agreement to lead to further peaceful resolution of issues, relations between the two countries soon deteriorated. On 15 March 1939, Germany breached the terms of the agreement by invading and occupying the remnants of the Czech state.

On 29 March, Leslie Hore-Belisha, the secretary of state for war

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, announced Britain's plans to increase the Territorial Army (TA) from 130,000 to 340,000 men and double the number of TA divisions. The plan was for existing TA divisions, referred to as the first-line, to recruit over their establishments (aided by an increase in pay for Territorials, the removal of restrictions on promotion which had hindered recruiting, construction of better-quality barracks, and an increase in supper rations) and then form a new division, known as the second-line, from cadres around which the new divisions could be expanded. This process was dubbed "duplicating". The 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division provided cadres to create a second-line "duplicate" formation, which became the 46th Infantry Division. Despite the intention for the army to grow, a lack of central guidance on the expansion and duplication process, and a lack of facilities, equipment, and instructors complicated the programme. In April 1939, 34,500 men, all aged 20, were conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

into the regular army, initially to be trained for six months before being deployed to the forming second-line units. The War Office had envisioned that the duplication process, and recruiting the required numbers of men, would take no more than six months. The process varied widely between the TA divisions. Some were ready in weeks while others had made little progress by the time the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

began on 1 September.

History

Formation

On 2 October 1939, the 46th Infantry Division became active. The division took control of the 137th, the 138th, and the 139th InfantryBrigades

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

...

, in addition to supporting divisional units, which had been administered by the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division. Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Algernon Ransome, who was called out of retirement and had previously commanded a brigade in the British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which cou ...

during the mid-1930s, was made the general officer commanding (GOC). The 137th Brigade had been created as the second-line duplicate of the 147th Infantry Brigade, and comprised the 2/5th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment

)

, march = ''Ça Ira''

, battles = Namur FontenoyFalkirk Culloden Brandywine

, anniversaries = Imphal (22 June)

The West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales's Own) (14th Foot) wa ...

; the 2/6th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's Regiment

The Duke of Wellington's Regiment (West Riding) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, forming part of the King's Division.

In 1702, Colonel George Hastings, 8th Earl of Huntingdon, was authorised to raise a new regiment, which he di ...

(2/6DWR); and the 2/7DWR. The 138th Brigade was raised as the duplicate of the 146th Infantry Brigade and consisted of the 6th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment

The Royal Lincolnshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army raised on 20 June 1685 as the Earl of Bath's Regiment for its first Colonel, John Granville, 1st Earl of Bath. In 1751, it was numbered like most other Army regiments ...

; the 2/4th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) was a light infantry regiment of the British Army. It officially existed from 1881 to 1968, but its predecessors go back to 1755. In 1968, the regiment was amalgamated with the Somerset and Cornwall ...

(2/4KOYLI); and the 6th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

The York and Lancaster Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army that existed from 1881 until 1968. The regiment was created in the Childers Reforms of 1881 by the amalgamation of the 65th (2nd Yorkshire, North Riding) Regiment ...

. The 139th Infantry Brigade was the second-line duplicate of the 148th Infantry Brigade, and on formation comprised the 2/5th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment (2/5LR); the 2/5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters

The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence for just under 90 years, from 1881 to 1970. In 1970, the regiment was amalgamated with the Worcestershire Regiment to ...

; and the 9th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters.

Because of the lack of official guidance, the newly formed units were at liberty to choose numbers, styles, and titles. The division adopted the number of their First World War counterpart, the 46th (North Midland) Division, but did not include a county within the name of the division. The division's battalions

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

were drawn largely from the English North Midlands. To denote the association of the division with this area, a Sherwood Forest

Sherwood Forest is a royal forest in Nottinghamshire, England, famous because of its historic association with the legend of Robin Hood.

The area has been wooded since the end of the Last Glacial Period (as attested by pollen sampling cor ...

oak tree was chosen as the divisional insignia. The Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

wrote that, "in addition, the oak was seen as an emblem of strength and reliability".

Initial service and transfer to France

The war deployment plan for the TA envisioned its divisions being sent overseas, as equipment became available, to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that had been already dispatched to Europe. The TA would join regular army divisions in waves as its divisions completed their training, the final divisions deploying a year after the war began. However, there was a need for men to guard strategically important locations, known as vulnerable points, and the division was primarily assigned to this duty until December 1939. This impacted training and spread the division out over a wide geographical area. While the division was ill-equipped and lacked transportation, it was assigned to anti-invasion duties in Yorkshire after the end of its guard-duty detail. On 5 December 1939, Major-General Henry Curtis took over command of the division; Curtis had previously commanded an infantry brigade within the BEF. At this point, the division was allocated a role within the defensive anti-invasion plan, codenamed Julius Caesar. Divisions assigned to this role, were tasked with launching an immediate attack on German parachutists. If that was not possible, the division was to cordon off and immobilise any German invasion effort until relieved by forces capable of launching a majorcounter-attack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

to defeat the Germans.

As 1939 turned into 1940, the division became caught up in an effort to address manpower shortages among the BEF's rear-echelon units. More men were needed to work along the line of communication

A line of communication (or communications) is the route that connects an operating military unit with its supply base. Supplies and reinforcements are transported along the line of communication. Therefore, a secure and open line of communicat ...

, and the army had estimated that by mid-1940 it would need at least 60,000 pioneers. The lack of such men had taxed the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is head ...

and Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps

The Royal Pioneer Corps was a British Army combatant corps used for light engineering tasks. It was formed in 1939, and amalgamated into the Royal Logistic Corps in 1993. Pioneer units performed a wide variety of tasks in all theatres of war, in ...

, and had also impacted frontline units that had to divert men from training to help construct defensive positions along the Franco-Belgian border. To address this issue, it was decided to deploy untrained territorial units as an unskilled workforce, thereby alleviating the strain on the existing pioneer units and freeing up regular units to complete their training. As a result, the decision was made to deploy the 12th (Eastern), 23rd (Northumbrian), and the 46th Infantry Divisions to France. Each division would leave their heavy equipment and most of their logistical, administrative, and support units behind. In total, the elements of the three divisions transported to France amounted to 18,347 men. The 46th Division was deployed to Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. The 137th Brigade was sent to aid in the unloading of supplies at Saint-Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocea ...

and Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

, as well as helping construct railway sidings in that area. The other two brigades were deployed to Rennes

Rennes (; br, Roazhon ; Gallo: ''Resnn''; ) is a city in the east of Brittany in northwestern France at the confluence of the Ille and the Vilaine. Rennes is the prefecture of the region of Brittany, as well as the Ille-et-Vilaine departme ...

to assist in railway construction and aid the transportation of ammunition supplies. The intent was that by August their job would be completed and they could return to the United Kingdom to resume training before being redeployed to France as front-line soldiers. The Army believed that this diversion from guard duty would also raise morale. Lionel Ellis

Lionel Frederic Ellis CVO CBE DSO MC (13 May 1885 – 19 October 1970) was a British Army officer and military historian, author of three volumes of the official ''History of the Second World War''.

Between the two World Wars, he was General ...

, the author of the British official history of the BEF in France, wrote that while the divisions "were neither fully trained nor equipped for fighting ... a balanced programme of training was carried out so far as time permitted". Historian Tim Lynch commented the deployment also had a political dimension, allowing "British politicians to tell their French counterparts that Britain had supplied three more infantry divisions towards the promised nineteen by the end of the year."

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside (30 November 1016; , ; sometimes also known as Edmund II) was King of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. He was the son of King Æthelred the Unready and his first wife, Ælfgifu of York. Edmund's reign was marred by ...

, chief of the imperial general staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

, was opposed to such a use of these divisions. He reluctantly caved to the political pressure to release the divisions, having been assured by General Lord Gort

Field Marshal John Standish Surtees Prendergast Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort, (10 July 1886 – 31 March 1946) was a senior British Army officer. As a young officer during the First World War, he was decorated with the Victoria Cross for his actio ...

(commander of the BEF) that the troops would not be used as frontline combat formations. The 46th Division departed Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

on 28 April and arrived at Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

the following day. Each of the division's nine battalions were equipped with four mortars, 18 Bren light machine gun

The Bren gun was a series of light machine guns (LMG) made by Britain in the 1930s and used in various roles until 1992. While best known for its role as the British and Commonwealth forces' primary infantry LMG in World War II, it was also used ...

s, 10 Boys anti-tank rifle

The Boys anti-tank rifle (officially Rifle, Anti-Tank, .55in, Boys, and sometimes incorrectly spelled "Boyes"), is a British anti-tank rifle used during the Second World War. It was often nicknamed the " elephant gun" by its users due to its ...

s and 12 trucks. This placed the division below its establishment of 108 two-inch mortars, 361 anti-tank rifles, and 810 trucks for transporting troops; but over the required establishment of 28 Bren guns.

Battle of France

Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

—the period of inactivity on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

since the start of the conflict—ended as the German military invaded Belgium and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. As a result, most of the BEF along with the best French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

armies and their strategic reserves moved forward to assist the Belgian and Dutch armies. While these forces attempted to stem the tide of the German advance, the main German assault pushed through the Ardennes Forest and crossed the River Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a t ...

. This initiated the Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and its allies, ...

and threatened to split the Allied armies in two, separating those in Belgium from the rest of the French military along the Franco-German border. The 46th Division was ordered to concentrate on the Belgian border, to act as a reserve to the BEF. As the German threat developed, Gort created an ad hoc force known as Macforce. This force was to protect the BEF's right-rear flank and lines of communication

A line of communication (or communications) is the route that connects an operating military unit with its supply base. Supplies and reinforcements are transported along the line of communication. Therefore, a secure and open line of communicati ...

, and prevent the Germans from crossing the River Scarpe.

On 15 May, the 138th and the 139th Brigades boarded trains and moved east. The men expected to be assigned to rear-area duties, such as clearing supply lines of refugees. However, once they arrived the next day, they were assigned to Macforce, and ordered to take up defensive positions along the Scarpe. These positions were occupied on 20 May, and the river was found to be less than deep and not a defensible position. The 137th Brigade and the divisional headquarters arrived in the Seclin

Seclin () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. It is part of the Métropole Européenne de Lille.

Population

Notable residents

* Andre Ayew, Ghana national football team footballer

*Victor Mollet, architect

*Jonathan Rouss ...

area, on the outskirts of Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the No ...

, on 20 May. There, the division took command of the 25th Infantry Brigade and other assets assigned by Gort, and were dubbed Polforce (after the town of St Pol where the units were waiting). These two brigades were assigned to defend the La Bassée

La Bassée () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Population

Heraldry

Personalities

La Bassée was the birthplace of the painter and draftsman Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761–1845).

Another native was Ignace François ...

Canal between Aire

Aire may refer to:

Music

* ''Aire'' (Yuri album), 1987

* ''Aire'' (Pablo Ruiz album), 1997

*''Aire (Versión Día)'', an album by Jesse & Joy

Places

*Aire-sur-la-Lys, a town in the Pas-de-Calais département in France

*Aire-la-Ville, a municip ...

and Carvin

Carvin () is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France.

Geography

An ex-coalmining commune, now a light industrial and farming town, situated some northeast of Lens, completely encircled by the N17 and ...

, a front of , on the flank of Macforce. With insufficient forces to cover the entire area, they had to defend and prepare to destroy 44 bridges. The stream of refugees moving through the area impeded this duty. The water obstacles posed the only natural barrier between the advancing German armour forces and the rear of the BEF, and potential catastrophic defeat.

With assets being moved between Polforce and Macforce, the division was unable to fight as a cohesive entity. The divisional history, written by division staff, stated the brigades fought "confused, independent and one‐sided" battles. Most notably, they record the 137th Brigade suffering "grievous casualties" when German forces broke through their positions on the La Bassée Canal. Meanwhile, with the BEF surrounded and the military situation in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

having deteriorated, the decision was made to evacuate the BEF from Dunkirk, the only remaining port in British hands. The remnants of the division's brigades retreated north towards the port. On 29 May, the division was assigned to defensive positions along the Canal de Bergues

The Canal de Bergues is one of the oldest canals in Flanders, its course being shown on a map dating from the 9th century, connecting Bergues to the port of Dunkerque, in northern France. The town itself, heavily fortified by Vauban in the late ...

and Nieuwpoort-Dunkirk Canal, on the Dunkirk perimeter. On 1 June, the division faced a major German attack, which involved bitter fighting, artillery barrages and heavy casualties. During the day, the division withdrew into Dunkirk and was subsequently evacuated via the mole or from the beaches. The 2/4KOYLI, the 2/6DWR, and the 2/7DWR had become separated from the division during the move from Rennes and were located on the southern side of the German advance into France. As they were unable to retreat towards or evacuate from Dunkirk, these battalions retreated west across France, with the 2/4KOYLI being heavily engaged in the defence of bridges crossing the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/ Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributa ...

at Pont-de-l'Arche

Pont-de-l'Arche () is a commune of the Eure ''département'' in France. Notable monuments include the parish church of Notre-Dame-des-Arts, which was built in the late Flamboyant style.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Eure department

T ...

. These battalions eventually reached Cherbourg and Saint-Nazaire, and were evacuated as part of Operation Aerial

Operation Aerial was the evacuation of Allied forces and civilians from ports in western France from 15 to 25 June 1940 during the Second World War. The evacuation followed the Allied military collapse in the Battle of France against Nazi Germ ...

.

Home defence

After returning to the United Kingdom, the division moved to

After returning to the United Kingdom, the division moved to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

, and the process of rebuilding it began. Curtis was reassigned to the 49th Division, and replaced by Major-General Desmond Anderson

Lieutenant-General Sir Desmond Francis Anderson (5 July 1885 – 29 January 1967) was a senior British Army officer in both the First and the Second World Wars.

Early life and First World War

Anderson was born in Dunham Massey and attended R ...

(previously the GOC of the 45th Infantry Division) on 5 July. In late July, the division relocated to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and was placed under the authority of Scottish Command

Scottish Command or Army Headquarters Scotland (from 1972) is a command of the British Army.

History Early history

Great Britain was divided into military districts on the outbreak of war with France in 1793. The Scottish District was comman ...

. The Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

field regiments from the 49th Division were then assigned to the division, replacing those that were detached prior to the 46th Division's departure to France. This was followed by the engineer, signal, and other support units being brought up to full strength. The divisional history claims, "within little more than a month of Dunkirk", the division "was better equipped than it had ever been in the dark days in France". On 27 July, Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Sec ...

, the commander-in-chief, Home Forces

Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces was a senior officer in the British Army during the First and Second World Wars. The role of the appointment was firstly to oversee the training and equipment of formations in preparation for their deployment ove ...

, visited the division. He recorded in his diary that he found the division "in a lamentably backward state of training, barely fit to do platoon

A platoon is a military unit typically composed of two or more squads, sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the branch, but a platoon can be composed of 50 people, although specific platoons may rang ...

training and deficient of officers".

The division was based initially along the Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross ...

coastline, to prevent any potential German landings, before it moved to Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from t ...

. There the division trained for the remainder of 1940. On 14 December, Anderson was promoted to lieutenant-general and replaced by Major-General Charles Edward Hudson

Brigadier Charles Edward Hudson, (29 May 1892 – 4 April 1959) was a British Army officer and an English recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwea ...

as GOC; Hudson was a distinguished First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

veteran and a recipient of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

(VC), who had previously commanded the 2nd Infantry Brigade during the fighting in France. In January 1941, the division left Scotland and travelled to Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire to t ...

. Subsequently, it moved to Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

where it undertook varying duties alongside training; anti-invasion duties that included manning coastal defences, airfield defence, and training Home Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the American Civil War, starting w ...

battalions. The division also conducted field exercises

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic s ...

across East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

.

On 22 May, Major-General Douglas Wimberley

Major-General Douglas Neil Wimberley, (15 August 1896 – 26 August 1983) was a British Army officer who, during the Second World War, commanded the 51st (Highland) Division for two years, from 1941 to 1943, notably at the Second Battle of El ...

briefly took command of the division, after Hudson was demoted on the grounds of being unfit for command of a division. In June, Major-General Miles Dempsey

General Sir Miles Christopher Dempsey, (15 December 1896 – 5 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. During the Second World War he commanded the Second Army in north west Europe. A highly professional an ...

replaced Wimberley, who was reassigned to command the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division. On 24 June, Brooke inspected the division again and noted the improvement in the soldiers' training since his last visit. At the end of October, Dempsey was assigned to the 42nd (East Lancashire) Infantry Division

The 42nd (East Lancashire) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army. The division was raised in 1908 as part of the Territorial Force (TF), originally as the East Lancashire Division, and was redesignated as the 42nd (Ea ...

to lead it during its conversion into an armoured division. Dempsey was replaced by Major-General Harold Freeman-Attwood

Major General Harold Augustus Freeman-Attwood, (30 December 1897 – 22 September 1963) was a British Army officer who fought in both World Wars.

Early life and military career

Born Harold Freeman on 30 December 1897, he was the eldest son of E ...

, and the division moved to Kent in November. In Kent, the division established a 'Battle School', and spent the remainder of 1941 and the majority of 1942 training and undertaking exercises. During this period, the division was brought up to full strength. Notably, the division conducted an exercise on Lewes Downs that was watched by Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower. On 19 July, the 137th Brigade left, temporarily reducing the division to two brigades. The 128th Infantry Brigade replaced it on 15 August. This brigade was composed of the 1/4th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment

The Hampshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881 by the amalgamation of the 37th (North Hampshire) Regiment of Foot and the 67th (South Hampshire) Regiment of Foot. The regim ...

(1/4HR), the 2/4HR, and the 5HR.

During late 1941 and through into 1942, British military planners considered a landing in French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. I ...

and subsequent advance into Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

. After various inceptions, Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while al ...

was crafted and the British First Army formed. On 24 August, the division was assigned to the First Army, but was not allocated to the initial invasion. Instead, the division remained in the United Kingdom. It assembled at Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alder ...

in December, and was also inspected by King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of Indi ...

.

Tunisia

On 24 December 1942, 4,000 men of the 139th Infantry Brigade and supporting forces departed fromLiverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

. The convoy arrived in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

, French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

, on 3 January 1943, followed by a road and rail journey to the frontline near Sedjenane, French Tunisia

The French protectorate of Tunisia (french: Protectorat français de Tunisie; ar, الحماية الفرنسية في تونس '), commonly referred to as simply French Tunisia, was established in 1881, during the French colonial Empire era, ...

. Meanwhile, on 6 January, the 128th Brigade departed from Gourock

Gourock ( ; gd, Guireag ) is a town in the Inverclyde council area and formerly a burgh of the County of Renfrew in the west of Scotland. It was a seaside resort on the East shore of the upper Firth of Clyde. Its main function today is as a ...

, Scotland, and the 138th Brigade departed from Liverpool. They arrived in Algeria on 17 January. While the 138th moved across land, the 128th Brigade re-boarded ships and were transported further down the Algerian coast to Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

. During this move, an Axis air attack resulted in one ship being sunk and the loss of materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

. Both brigades moved up to the front during February.

On 10 January, the 139th Infantry Brigade launched a minor attack upon Italian positions, but an Axis offensive postponed further efforts. The Italian-German forces struck at Allied positions in western Tunisia to gain more favourable defensive positions from which to contend with the expected Allied offensive. This offensive began with the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid, aimed at largely American positions. The Axis offensive expanded with the Battle of Kasserine Pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a series of battles of the Tunisian campaign of World War II that took place in February 1943 at Kasserine Pass, a gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia.

The Axis forces, ...

. In response, the 2/5LR, along with anti-tank guns and artillery pieces from the 139th Brigade, were moved south to Thala to bolster Allied positions. Once there, they covered the withdrawal of American and British forces, repulsed a German tank attack late on 20 February after heavy fighting that saw German units penetrate their position and aided in the subsequent defence of the town. The fighting cost these units over 400 casualties. To the north, patrols from the 5HR (128th Infantry Brigade) clashed with their German counterparts near Sidi Nsir.

On 26 February, the 5HR became embroiled in the opening moves of Operation Ochsenkopf, another major German attack. Ochsenkopf aimed to capture the town of Béja

Béja ( ar, باجة ') is a city in Tunisia. It is the capital of the Béja Governorate. It is located from Tunis, between the Medjerdah River and the Mediterranean, against the foothills of the Khroumire, the town of Béja is situated on the ...

. After a 24-hour battle, which included three German tanks being disabled, the battalion was reduced to 120 men and forced back. The following day, the Germans attacked towards Hunt's Gap where the reinforced 128th Brigade (including the Churchill tank

The Tank, Infantry, Mk IV (A22) Churchill was a British infantry tank used in the Second World War, best known for its heavy armour, large longitudinal chassis with all-around tracks with multiple bogies, its ability to climb steep slopes, ...

-equipped North Irish Horse

The North Irish Horse was a yeomanry unit of the British Territorial Army raised in the northern counties of Ireland in the aftermath of the Second Boer War. Raised and patronised by the nobility from its inception to the present day, it was o ...

) was concentrated. Fighting raged until 3 March, by which time the brigade had halted the German effort to capture Béja and destroyed at least 11 tanks. At the same time, on 26 February, Axis forces advanced into the Sedjenane valley, held by the 139th Brigade, initiating the Battle of Sedjenane

Sedjenane is a town in northern Tunisia, on the railway line to Mateur and the port of Bizerta. The Battle of Sedjenane was fought during World War II between the Allies of World War II, Allies and Axis powers, Axis for control of a town in north ...

. Notably, on 2 March, the 16th Durham Light Infantry (16DLI) launched a counterattack that failed with heavy casualties. By 4 March, the brigade had been forced to withdraw. During the following two weeks, the brigade launched local counterattacks and engaged in further back-and-forth fighting in isolated company and battalion actions. Starting on 27 March, the division launched larger counterattacks to regain the Sedjenane valley. During this, the division took temporary command of the 1st Parachute and the 38th (Irish) Brigades. They, alongside the 138th Brigade, retook all the territory that had been lost by 1 April, as well around 1,000 prisoners.

On 2 April, the 128th Brigade moved south to assist in an attack towards Pichon, near Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

. This was part of a larger effort to intercept Axis forces retreating north, from the south of Tunisia where they were being chased by the British Eighth Army. The resulting fighting was a success for the brigade who took 150 prisoners, but the overall attack failed to trap Axis forces. They marched north to rejoin the main body of the division on 14 April. The division was next tasked with capturing hills northeast of Bou Arada

Bou Arada is a town and commune in the Siliana Governorate, Tunisia. As of 2004 it had a population of 12,273.

to open the way for an armoured advance towards Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

. On 21 April, Axis forces launched a minor spoiling attack that was repelled before the division attacked. Over the next two days, in heavy fighting, the division took its objectives. Further back-and-forth fighting followed as the division was called upon to clear additional Axis positions. Fighting ended on 27 April and so did the division's role in the campaign. On 20 May, elements of the 46th took part in the victory parade in Tunis.

The division was not allocated to the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It b ...

and remained in Tunisia. In June, the division took part in Exercise Conqueror, a training exercise, where it opposed an amphibious landing conducted by the United States 1st Infantry Division. This was followed by the 46th conducting amphibious landing training, as it was assigned to Operation Buttress, a proposed landing across the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily ( Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian S ...

on mainland Italy. This operation did not occur, and the division was allotted to Operation Avalanche; the Allied invasion of mainland Italy at Salerno. In August, the division undertook Exercise Dryshod as a final rehearsal for this landing. During the exercise, a truck containing land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s exploded, killing 15 men and injuring around 30 more. On 25 August, Major-General John Hawkesworth took command.

Italian campaign

Salerno beachhead

The division embarked and sailed from Africa on 7 September, assigned to the British X Corps, part of the US Fifth Army. The division was to land near

The division embarked and sailed from Africa on 7 September, assigned to the British X Corps, part of the US Fifth Army. The division was to land near Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

and capture it and then assist in the capture of the port of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

. En route, the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

'' attacked the convoy, with one ship hit. The next day, the Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Bri ...

, the Italian surrender, was announced. As the ships neared shore, they were engaged by German artillery. Supported by a naval bombardment, the division landed under the cover of dark with at least one battalion landed in the wrong area. Mines and German resistance impeded the advance from the beach, and during the day the 16th Panzer Division launched counterattacks with tanks and self-propelled guns. By the end of the day, Salerno had been captured, and the division had suffered 350 casualties. Over the next two weeks, fierce fighting occurred as the Germans launched a major counterattack by six divisions against the various Allied landing zones. In the 46th Division's sector, the counterattack was conducted by the Hermann Göring Panzer Division Hermann or Herrmann may refer to:

* Hermann (name), list of people with this name

* Arminius, chieftain of the Germanic Cherusci tribe in the 1st century, known as Hermann in the German language

* Éditions Hermann, French publisher

* Hermann, M ...

, the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, and the 15th Panzergrenadier Division. The fighting saw ongoing artillery fire on the 46th's landing zone and support ships, Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

shell fire against German positions, tank attacks, back-and-forth fighting, hand-to-hand combat and bayonet charges. In places, the division was forced back, but Salerno was held throughout. By 13 September, the ongoing heavy fighting made the Allied commanders consider withdrawing the landed troops. Particularly heavy fighting occurred for a hill near Salerno dubbed White Cross Hill. A German attack forced the division off the hill, which was followed by repeated failed counterattacks. Having only been retaken once, the Germans withdrew. Other major attacks were launched upon the division and repulsed. By 16 September, the German counterattack ended and their forces began to withdraw.

Volturno Line to the Winter Line

On 22 September, the division advanced north, and captured several villages and hills after overcoming German resistance. This helped clear the way for the 7th Armoured Division to be employed. They began their advance on 28 September and entered Naples on 1 October. During September, drafts were brought in to replace the 46th Division's casualties. Some of these drafts mutinied, in what became known as the Salerno mutiny, because they were not being reassigned to their former units.

In October, the division attacked the German

On 22 September, the division advanced north, and captured several villages and hills after overcoming German resistance. This helped clear the way for the 7th Armoured Division to be employed. They began their advance on 28 September and entered Naples on 1 October. During September, drafts were brought in to replace the 46th Division's casualties. Some of these drafts mutinied, in what became known as the Salerno mutiny, because they were not being reassigned to their former units.

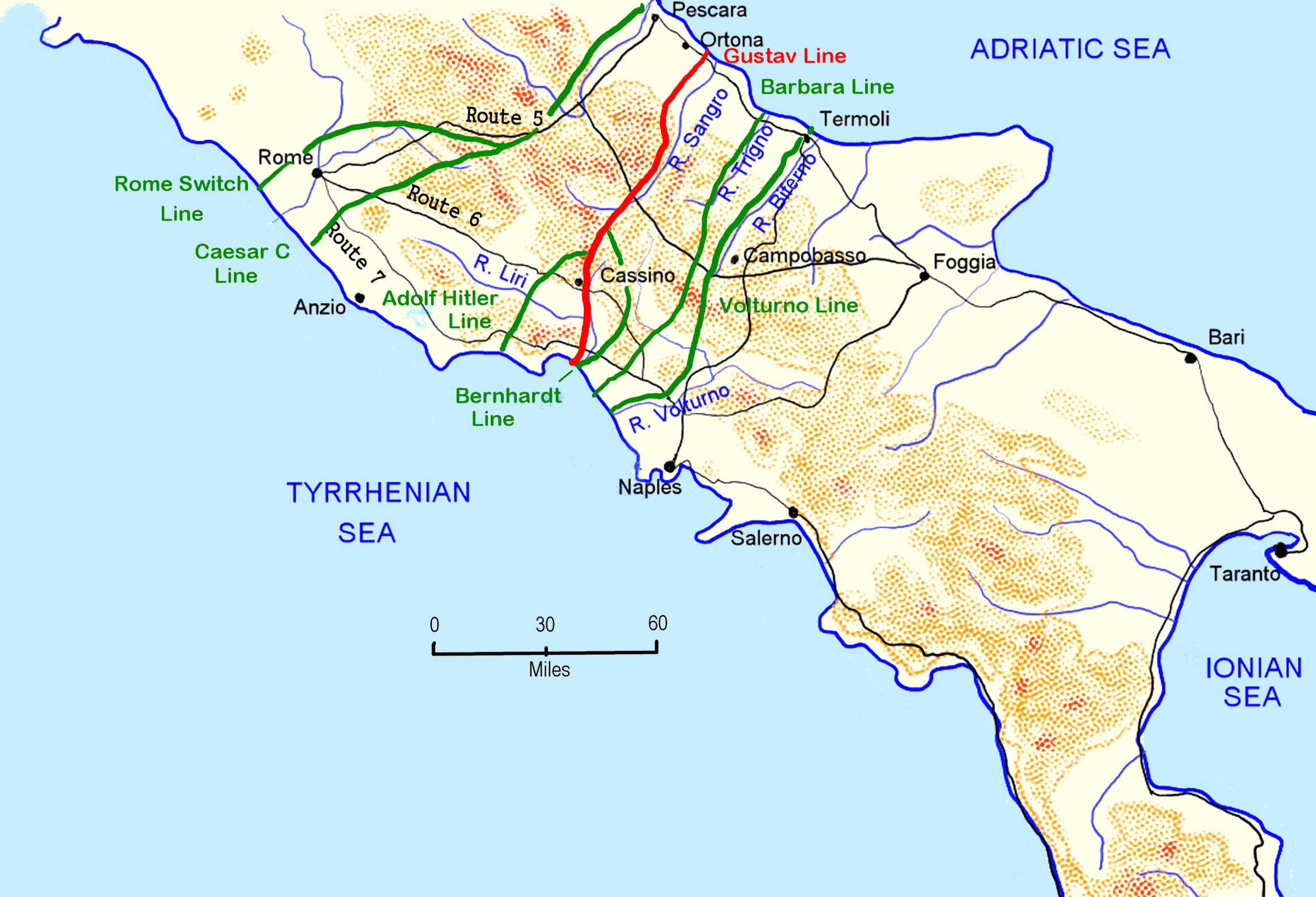

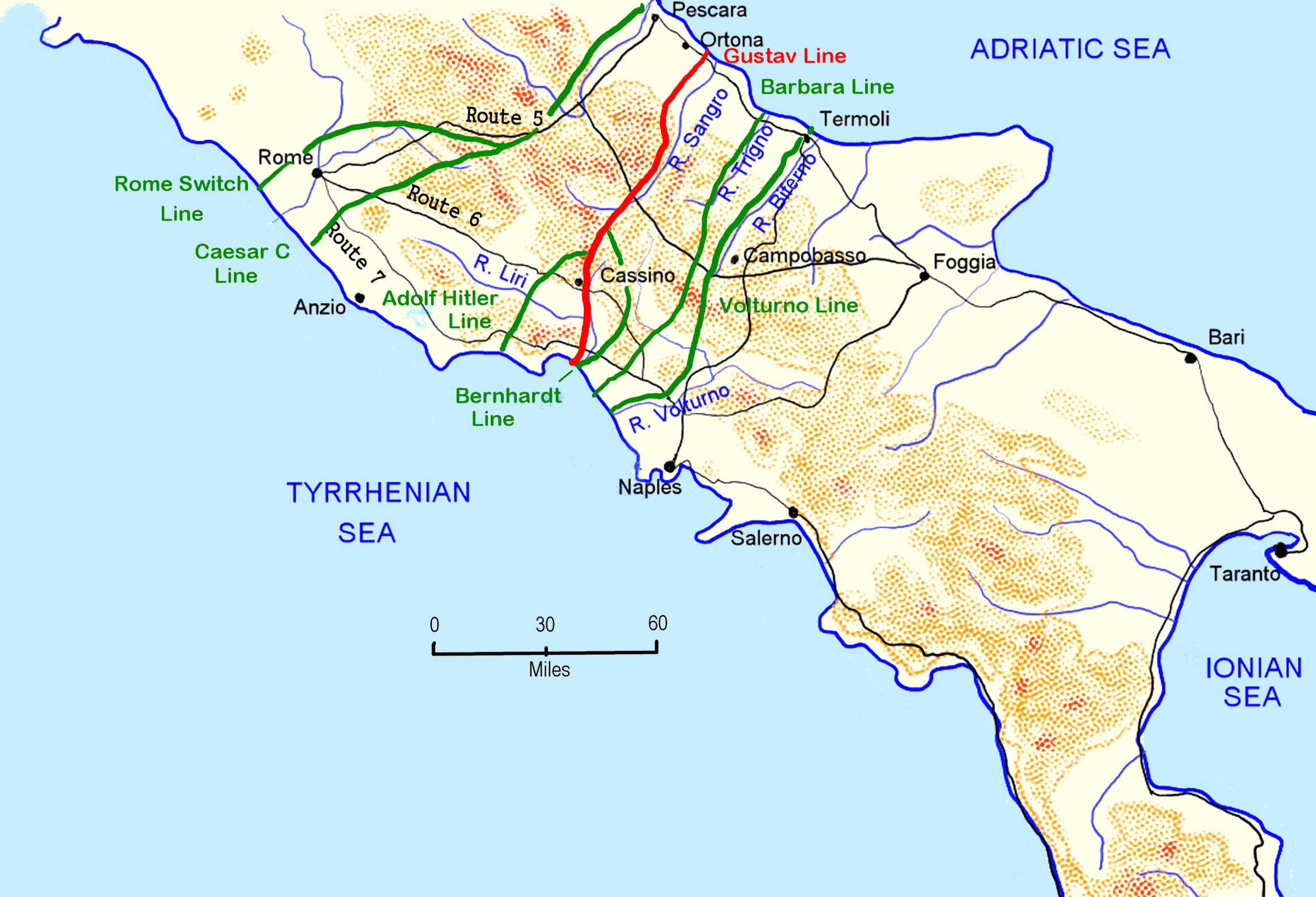

In October, the division attacked the German Volturno Line

The Volturno Line (also known as the Viktor Line; , ) was a German defensive position in Italy during the Italian Campaign of World War II.

The line ran from Termoli in the east, along the Biferno River through the Apennine Mountains to the ...

, based along the River Volturno. An initial bridgehead was captured on 6 October, but the main attack did not occur for another six days. Hugging the coastline, the division seized additional crossings. By 15 October, it had advanced beyond the river to a series of canals that formed the main defensive position of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division. This obstacle was overcome by 18 October, and bridges were constructed. Due to the success achieved by the 56th (London) Infantry Division, near Capua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrus ...

, the 46th Division was moved further inland. They launched new attacks on 29 October, which breached the Barbara Line

During the Italian Campaign of World War II, the Barbara Line was a series of German military fortifications in Italy, some south of the Gustav Line, from Colli al Volturno to the Adriatic Coast in San Salvo and a similar distance north of t ...

. Sessa was taken on 1 November, and they reached the Garigliano River the next day. On 1 December, the division launched its first attack on the Bernhardt Line

The Bernhardt Line (or Reinhard Line) was a German defensive line in Italy during the Italian Campaign of World War II. Having reached the Bernhardt Line at the start of December 1943, it took until mid-January 1944 for the U.S. Fifth Army to fig ...

. This attack was diversionary, to assist the 56th Division in their main effort, and involved a failed attempt to take the village of Calabritto

Calabritto (Irpino: ) is an Italian town and a commune in the province of Avellino, Campania, Italy. It occupies a hilly-mountainous area at the eastern tip of the Monti Picentini range.

History

The town was struck by the 1980 Irpinia earthquak ...

. German troops, dug-in around the village, repulsed the division, and it was not until the 56th Division cleared the nearby high ground that the 46th was able to capture the village on 6 December.

The next series of battles were efforts to breach the Winter Line

The Winter Line was a series of German and Italian military fortifications in Italy, constructed during World War II by Organisation Todt and commanded by Albert Kesselring. The series of three lines was designed to defend a western section ...

and became part of the opening phase of the Battle of Monte Cassino

The Battle of Monte Cassino, also known as the Battle for Rome and the Battle for Cassino, was a series of four assaults made by the Allies against German forces in Italy during the Italian Campaign of World War II. The ultimate objective was ...

. On 19 January 1944, the division made three attempts to cross the Garigliano, at the confluence of the rivers Liri

The Liri (Latin Liris or Lyris, previously, Clanis; Greek: ) is one of the principal rivers of central Italy, flowing into the Tyrrhenian Sea a little below Minturno under the name Garigliano.

Source and route

The Liri's source is in the ...

and Gari. The swift current and German resistance defeated these efforts. DUKW

The DUKW (colloquially known as Duck) is a six-wheel-drive amphibious modification of the -ton CCKW trucks used by the U.S. military during World War II and the Korean War.

Designed by a partnership under military auspices of Sparkman & Step ...

s, which had been available, had been withdrawn for training exercises to prepare for the upcoming landing at Anzio and were sorely missed. While the division's attack failed, it helped in drawing vital German reinforcements towards it and away from the Anzio

Anzio (, also , ) is a town and '' comune'' on the coast of the Lazio region of Italy, about south of Rome.

Well known for its seaside harbour setting, it is a fishing port and a departure point for ferries and hydroplanes to the Pontine Isl ...

area. The failed attack potentially hindered an American attack that occurred the next day, during the Battle of Rapido River

The Battle of Rapido River was fought from 20 to 22 January 1944 during one of the Allies' many attempts to breach the Winter Line in the Italian Campaign during World War II. Despite its name, the battle occurred on the Gari River.

, as the 46th had not captured vital terrain on the American southern flank. The 56th (London) Infantry Division, to the 46th's south, had secured a bridgehead across the Garigliano and the 46th Division crossed the river. On the night of 26/27 January, the division launched an attack into the Aurunci Mountains

The Monti Aurunci (or Aurunci Mountains) is a mountain range of southern Lazio, in central Italy. It is part of the Antiappennini, a group running from the Apennines chain to the Tyrrhenian Sea, where it forms the promontory of Gaeta. It is bound ...

near Castelforte

Castelforte is a town and '' comune'' in the province of Latina, in the Lazio region of central Italy. It is located at the feet of the Monti Aurunci massif.

History

Castelforte was founded most likely before the year 1000 AD. According to some ...

. The fighting continued until 10 February, by which point the division had captured a series of hilltops and helped push back the German 94th Infantry Division.

On 16 March, the division left Italy and arrived six days later in Egypt. At the end of the month, the division moved to Palestine, where it remained until June. During this time, the division refitted, rested, trained and took on almost 3,000 replacements, replacing the casualties it had suffered.

Gothic Line

The division left Palestine on 17 June 1944 and returned to Egypt to board ships for Italy. The division landed in Italy on 3 July and was assigned to the V Corps of the British Eighth Army. It then took up position near

The division left Palestine on 17 June 1944 and returned to Egypt to board ships for Italy. The division landed in Italy on 3 July and was assigned to the V Corps of the British Eighth Army. It then took up position near Bevagna

Bevagna is a town and ''comune'' in the central part of the Italian province of Perugia (Umbria), in the flood plain of the Topino river.

Bevagna is south-east of Perugia, west of Foligno, north-north-west of Montefalco, south of Assisi a ...

. In August, the Eighth Army developed Operation Olive, which called for the army to break through the Gothic Line

The Gothic Line (german: Gotenstellung; it, Linea Gotica) was a German defensive line of the Italian Campaign of World War II. It formed Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's last major line of defence along the summits of the northern part of ...

and enter the Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

.

On 25 August, the division (along with the majority of the Eighth Army) attacked. After steady progress, the division captured a series of villages and hills around Montegridolfo

Montegridolfo ( rgn, Mun't Gridòlf) is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Rimini in the Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about southeast of Bologna and about southeast of Rimini.

The municipality of Montegridolfo contains t ...

on 31 August. On the final day of the fighting, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

Gerard Norton eliminated two German positions by himself and was subsequently awarded the VC. On 2 September, the division repulsed a German armoured counterattack. Over the following days, the division mopped up the area and fended off further German counterattacks. By 4 September, the division had advanced and seized bridgeheads and nearby high ground across the River Conca. This allowed other elements of V Corps to advance forward, and division was allowed a period of rest.

On 10 September, the division attacked to clear the high ground on the Eighth Army's western flank. This fighting included a two-day battle for Gemmano

Gemmano ( rgn, Zman) is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Rimini in the Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about southeast of Bologna and about 15 km (9 mi) south of Rimini.

Gemmano borders the following municipalit ...

, which changed hands several times. Monte Colombo was captured soon after. On 15 September, the division made at least three assaults on Montescudo, with the village falling only after the Germans withdrew. Over the following days, the division pushed forward and cleared various ridges and villages held by German forces. They then brushed passed the border of the Republic of San Marino and captured Verucchio

Verucchio ( rgn, Vròcc) is a '' comune ''in the province of Rimini, region of Emilia-Romagna, Italy. It has a population of about 9,300 and is from Rimini, on a spur overlooking the valley of the Marecchia river.

History

Traces of a 12th-9t ...

on 21 September. During the rest of September, the division continued its advance and fought a heavily contested battle to seize a ridge beyond the River Marecchia. Weather then impeded progress, causing a one day delay in the crossing a river on 29 September, and then a six-day delay in the crossing of the Fiumicino

Fiumicino () is a town and comune in the Metropolitan City of Rome, Lazio, central Italy, with a population of 80,500 (2019). It is known for being the site of Leonardo da Vinci–Fiumicino Airport, the busiest airport in Italy and the eleventh-b ...

. Throughout October, the division fought a series of river-crossing actions that also required the ridges and hills beyond to be captured. During this period, the division was opposed by the 114th Jäger Division. On 20 October, Cesena

Cesena (; rgn, Cisêna) is a city and '' comune'' in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, served by Autostrada A14, and located near the Apennine Mountains, about from the Adriatic Sea. The total population is 97,137.

History

Cesena was ...

was captured, and the division linked up with the Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Socia ...

. The division was then rested. After an advance of since 25 August, the division had crossed ten rivers and had taken 2,000 prisoners.

On 6 November 1944, Major-General

On 6 November 1944, Major-General Stephen Weir

Major-General Sir Stephen Cyril Ettrick Weir, (5 October 1904 – 24 September 1969) was a New Zealand military leader and diplomat.

Born in Otago, Weir became a professional soldier in 1927. He served in a number of postings around the countr ...

, a New Zealand Military Forces

, image = New Zealand Army Logo.png

, image_size = 175px

, caption =

, start_date =

, country =

, branch = ...

officer who had commanded the 2nd New Zealand Division

The 2nd New Zealand Division, initially the New Zealand Division, was an infantry division of the New Zealand Military Forces (New Zealand's army) during the Second World War. The division was commanded for most of its existence by Lieutenant ...

previously, became GOC. The division returned to action the next day and helped clear the outskirts of Forlì

Forlì ( , ; rgn, Furlè ; la, Forum Livii) is a '' comune'' (municipality) and city in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, and is the capital of the province of Forlì-Cesena. It is the central city of Romagna.

The city is situated along the Vi ...

. Faced by the 26th Panzer and the 356th Infantry Divisions, the 46th fought another series of river-crossing actions through 20 November. On 3 December, after several days of preparation, the division advanced across the River Lamone and battled with the German 305th Infantry Division over the following four days. Under the cover of dark, on 9 December, the German 90th Panzergrenadier Division launched a counterattack. Heavy fighting would rage through to the next day before the German attack was repulsed. During this counterattack, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

John Brunt conducted an aggressive defence during two actions and helped retrieve wounded men who had been stranded between the lines. These actions resulted in him posthumously earning the VC, as he was killed the following day. From the landing at Salerno to the end of the campaign against the Gothic Line, the division suffered a total of 9,880 casualties. This included 1,447 killed, 6,476 wounded, and 1,957 missing. Between the two campaigns, the division captured 4,507 German soldiers.

Greece

At the end of August 1944, the majority of German military units in Greece began withdrawing because of theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's offensive into Romania and the latter changing sides. This was followed shortly after by Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

entering the war against Germany and the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод� ...

attacking German lines of communication. With German formations remaining only on a handful of Greek islands, the British moved forward with their plan to reoccupy the country. On 18 October, supported by British forces, the Greek government-in-exile

The Greek government-in-exile was formed in 1941, in the aftermath of the Battle of Greece and the subsequent occupation of Greece by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The government-in-exile was based in Cairo, Egypt, and hence it is also referr ...

returned to Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

; this was part of a larger geopolitical move to install a British-friendly, non-communist government in Greece. During the occupation, Britain had provided military support to the National Liberation Front (EAM), a combination of five socialist and communist parties, which controlled the large Greek People's Liberation Army

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

* Greeks, an ethnic group.

* Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

** Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ances ...

(ELAS). In early 1944, the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος}, ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom and ...

broke out between the EAM's forces and the non-communist partisan movements, such as the National Republican Greek League

The National Republican Greek League ( el, Εθνικός Δημοκρατικός Ελληνικός Σύνδεσμος (ΕΔΕΣ), ''Ethnikós Dimokratikós Ellinikós Sýndesmos'' (EDES)) was one of the major resistance groups formed during t ...

(EDES). After the re-establishment of the Government of Greece, tensions rose, culminating with the EAM attempting to seize power in December and the British military becoming involved within the second phase of the Greek Civil War.

On 28 November, the 46th Division's 139th Brigade was pulled off the frontline in Italy, and dispatched to Greece to replace the 2nd Parachute Brigade that was due to move to Italy. The Brigade landed at Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saro ...

on 4 December and immediately secured the town's police stations. Over the following days, as the rest of the brigade landed, it secured the area and contended with snipers, small skirmishes, house-to-house searches, and a prolonged battle to secure the railway station

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in Track (rail transport), tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the ...

. On 2 December, the 139th Brigade's 5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters was airlifted to Sedes Air Base

Sedes Airport is a military airport 15 km east of Thessaloniki, Greece, and 3 km northeast of Thessaloniki's Makedonia International Airport. Sedes airport started operating during the Balkan Warshttp://www.haf.gr/el/structure/units ...

. They entered Salonika