1950s American automobile culture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

1950s American automobile culture has had an enduring influence on the

1950s American automobile culture has had an enduring influence on the

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly called the Interstate System or simply the Interstate) is a network of

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly called the Interstate System or simply the Interstate) is a network of

After World War II, land developers began to buy land just outside the city limits of larger cities to build mass quantities of inexpensive tract houses. One of the first examples of planned suburbanization is

After World War II, land developers began to buy land just outside the city limits of larger cities to build mass quantities of inexpensive tract houses. One of the first examples of planned suburbanization is

As more middle-class and affluent people fled the city to the relative quiet and open spaces of the suburbs, the urban centers deteriorated and lost population. At the same time that cities were experiencing a lower tax base due to the flight of higher income earners, pressures from

As more middle-class and affluent people fled the city to the relative quiet and open spaces of the suburbs, the urban centers deteriorated and lost population. At the same time that cities were experiencing a lower tax base due to the flight of higher income earners, pressures from

The relative abundance and inexpensive nature of the

The relative abundance and inexpensive nature of the

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) is the second most popular spectator sports in the United States behind the

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) is the second most popular spectator sports in the United States behind the

As more Americans began driving cars, entirely new categories of businesses came into being to allow them to enjoy their products and services without having to leave their cars. This includes the

As more Americans began driving cars, entirely new categories of businesses came into being to allow them to enjoy their products and services without having to leave their cars. This includes the

Although drive-in movies first appeared in 1933, it was not until well after the post-war era that they became popular, enjoying their greatest success in the 1950s, reaching a peak of more than 4,000 theaters in the United States alone. Drive-in theaters have been romanticized in popular culture with the movie ''

Although drive-in movies first appeared in 1933, it was not until well after the post-war era that they became popular, enjoying their greatest success in the 1950s, reaching a peak of more than 4,000 theaters in the United States alone. Drive-in theaters have been romanticized in popular culture with the movie ''

The first modern shopping malls were built in the 1950s, such as

The first modern shopping malls were built in the 1950s, such as

Most new cars were sold through automobile dealerships in the 1950s, but

Most new cars were sold through automobile dealerships in the 1950s, but

''Hot Rod'' magazine covers from the 1950sThe old car manual project

History of the automobile American culture 1950s cars Society of the United States American studies Automotive industry in the United States 1950s in the United States Car culture

1950s American automobile culture has had an enduring influence on the

1950s American automobile culture has had an enduring influence on the culture of the United States

The culture of the United States of America is primarily of Western, and European origin, yet its influences includes the cultures of Asian American, African American, Latin American, and Native American peoples and their cultures. The U ...

, as reflected in popular music, major trends from the 1950s and mainstream acceptance of the "hot rod

Hot rods are typically American cars that might be old, classic, or modern and that have been rebuilt or modified with large engines optimised for speed and acceleration. One definition is: "a car that's been stripped down, souped up and made ...

" culture. The American manufacturing economy switched from producing war-related items to consumer goods

A final good or consumer good is a final product ready for sale that is used by the consumer to satisfy current wants or needs, unlike a intermediate good, which is used to produce other goods. A microwave oven or a bicycle is a final good, b ...

at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and by the end of the 1950s, one in six working Americans were employed either directly or indirectly in the automotive industry

The automotive industry comprises a wide range of companies and organizations involved in the design, development, manufacturing, marketing, and selling of motor vehicles. It is one of the world's largest industries by revenue (from 16 % ...

. The United States became the world's largest manufacturer of automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarded ...

s, and Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

's goal of 30 years earlier—that any man with a good job should be able to afford an automobile—was achieved. A new generation of service businesses focusing on customers with their automobiles came into being during the decade, including drive-through

A drive-through or drive-thru (a sensational spelling of the word ''through''), is a type of take-out service provided by a business that allows customers to purchase products without leaving their cars. The format was pioneered in the United ...

or drive-in

A drive-in is a facility (such as a restaurant or movie theater) where one can drive in with an automobile for service. At a drive-in restaurant, for example, customers park their vehicles and are usually served by staff who walk or rollerskat ...

restaurants and greatly increasing numbers of drive-in theater

A drive-in theater or drive-in cinema is a form of cinema structure consisting of a large outdoor movie screen, a projection booth, a concession stand, and a large parking area for automobiles. Within this enclosed area, customers can view movi ...

s (cinemas).

The decade began with 25 million registered automobiles on the road, most of which predated World War II and were in poor condition; no automobiles or parts were produced during the war owing to rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

and restrictions. By 1950, most factories had made the transition to a consumer-based economy, and more than 8 million cars were produced that year alone. By 1958, there were more than 67 million cars registered in the United States, more than twice the number at the start of the decade.

As part of the U.S. national defenses, to support military transport, the National Highway System was expanded with Interstate highways, beginning in 1955, across many parts of the United States. The wider, multi-lane highways allowed traffic to move at faster speeds, with few or no stoplight

Traffic lights, traffic signals, or stoplights – known also as robots in South Africa are signalling devices positioned at road intersections, pedestrian crossings, and other locations in order to control flows of traffic.

Traffic light ...

s on the way. The wide-open spaces along the highways became a basis for numerous billboard

A billboard (also called a hoarding in the UK and many other parts of the world) is a large outdoor advertising structure (a billing board), typically found in high-traffic areas such as alongside busy roads. Billboards present large adverti ...

s showing advertisements.

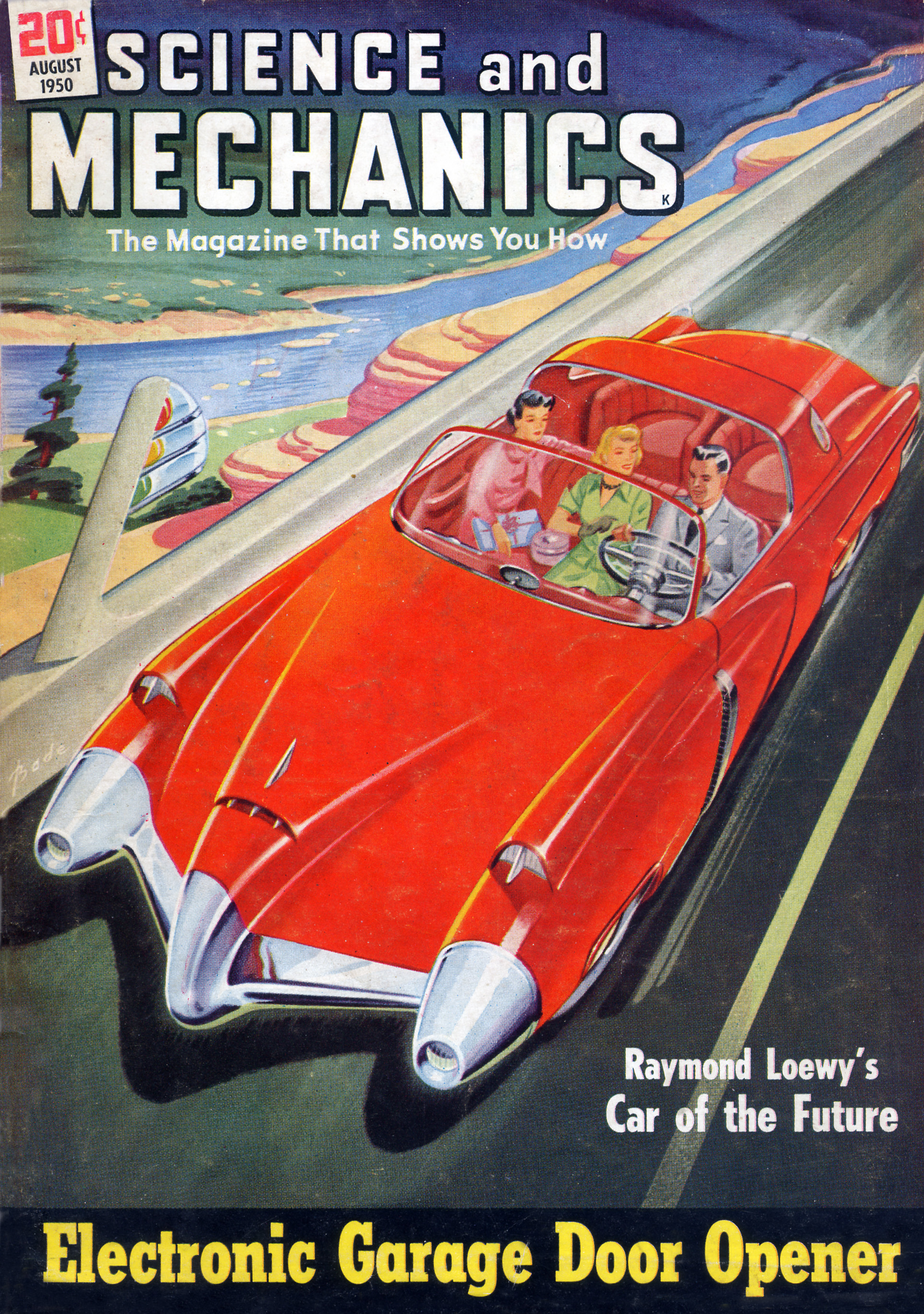

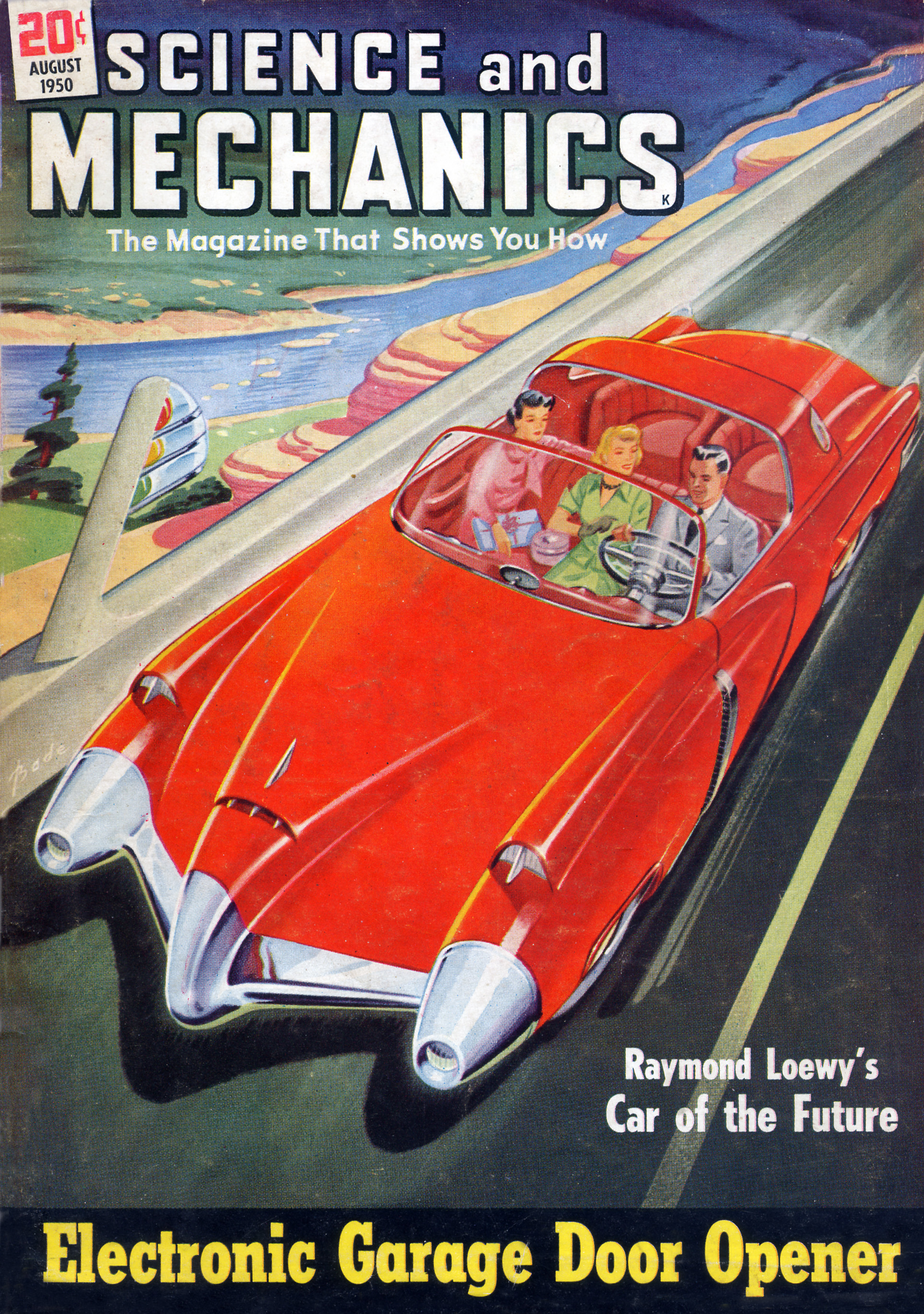

The dawning of the Space Age

The Space Age is a period encompassing the activities related to the Space Race, space exploration, space technology, and the cultural developments influenced by these events, beginning with the launch of Sputnik 1 during 1957, and continuing ...

and Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

were reflected in contemporary American automotive styling. Large tailfins

The tailfin era of automobile styling encompassed the 1950s and 1960s, peaking between 1955 and 1961. It was a style that spread worldwide, as car designers picked up styling trends from the US automobile industry, where it was regarded as the ...

, flowing designs reminiscent of rockets

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

, and radio antennas

In radio engineering, an antenna or aerial is the interface between radio waves propagating through space and electric currents moving in metal conductors, used with a transmitter or receiver. In transmission, a radio transmitter supplies an ...

that imitated Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

were common, owing to the efforts of design pioneers such as Harley Earl

Harley Jarvis Earl (November 22, 1893 – April 10, 1969) was an American automotive designer and business executive. He was the initial designated head of design at General Motors, later becoming vice president, the first top executive ever ...

.

Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly called the Interstate System or simply the Interstate) is a network of

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (commonly called the Interstate System or simply the Interstate) is a network of freeway

A controlled-access highway is a type of highway that has been designed for high-speed vehicular traffic, with all traffic flow—ingress and egress—regulated. Common English terms are freeway, motorway and expressway. Other similar terms ...

s that forms a part of the National Highway System of the United States.

While serving as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe during World War II, Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

had gained an appreciation of the German Autobahn

The (; German plural ) is the federal controlled-access highway system in Germany. The official German term is (abbreviated ''BAB''), which translates as 'federal motorway'. The literal meaning of the word is 'Federal Auto(mobile) Track' ...

network as an essential component of a national defense system, providing transport routes for military supplies and troop deployments. Construction was authorized by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, also known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, was enacted on June 29, 1956, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill into law. With an original authorization of $25 billion for ...

, and the original portion was completed 35 years later. The system has contributed in shaping the United States into a world economic superpower and a highly industrialized nation.

The Interstate grew quickly, along with the automobile industry, allowing a new-found mobility that permeated ways of American life and culture. The automobile and the Interstate became the American symbol of individuality and freedom, and, for the first time, automobile buyers accepted that the automobile they drove indicated their social standing and level of affluence. It became a statement of their personality and an extension of their self-concepts.

Suburbanization

The United States' investment in infrastructures such as highways and bridges coincided with the increasing availability of cars more suited to the higher speeds that better roads made possible, allowing people to live beyond the confines of major cities, and instead commute to and from work. After World War II, land developers began to buy land just outside the city limits of larger cities to build mass quantities of inexpensive tract houses. One of the first examples of planned suburbanization is

After World War II, land developers began to buy land just outside the city limits of larger cities to build mass quantities of inexpensive tract houses. One of the first examples of planned suburbanization is Levittown, Pennsylvania

Levittown is a census-designated place (CDP) and planned community in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is part of the Delaware Valley, Philadelphia metropolitan area. The population was 52,983 at the 2010 ...

, which was developed by William Levitt

William Jaird Levitt (February 11, 1907 – January 28, 1994) was an American real-estate developer and housing pioneer. As president of Levitt & Sons, he is widely credited as the father of modern American suburbia. He was named one of ''Time ...

beginning in 1951 as a suburb of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

. The promise of their own single-family home on their own land, together with a free college education and low-interest loans given to returning soldiers to purchase homes under the G.I. Bill, drove demand for new homes to an unprecedented level. Additionally, 4 million babies were born every year during the 1950s. By the end of the baby boom era in 1964, almost 77 million "baby boomers" had been born, fueling the need for more suburban housing, and automobiles to commute them to and from the city centers for work and shopping.

By the end of the 1950s, one-third of Americans lived in the suburbs. Eleven of the United States's twelve largest cities recorded a declining population during the decade, with a consequent loss in tax revenues and city culture. Only Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, a center for the car culture, gained population. Economist Richard Porter commented that "The automobile made suburbia possible, and the suburbs made the automobile essential."

Decline of the inner city

More people joined themiddle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

in the 1950s, with more money to spend, and the availability of consumer goods expanded along with the economy, including the automobile. Americans were spending more time in their automobiles and viewing them as an extension of their identity, which helped to fuel a boom in automobile sales. Most businesses directly or indirectly related to the auto industry saw tremendous growth during the decade. New designs and innovations appealed to a generation tuned into fashion and glamour, and the new-found freedom and way of life in the suburbs had several unforeseen consequences for the inner cities

The term ''inner city'' has been used, especially in the United States, as a euphemism for majority-minority lower-income residential districts that often refer to rundown neighborhoods, in a downtown or city centre area. Sociologists someti ...

. The 1950s saw the beginning of white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

and urban sprawl

Urban sprawl (also known as suburban sprawl or urban encroachment) is defined as "the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centers) on undeveloped land near a city." Urban sprawl has been described as the unrestricted growt ...

, driven by increasing automobile ownership. Many local and national transportation laws encouraged suburbanization, which in time ended up damaging the cities economically.

As more middle-class and affluent people fled the city to the relative quiet and open spaces of the suburbs, the urban centers deteriorated and lost population. At the same time that cities were experiencing a lower tax base due to the flight of higher income earners, pressures from

As more middle-class and affluent people fled the city to the relative quiet and open spaces of the suburbs, the urban centers deteriorated and lost population. At the same time that cities were experiencing a lower tax base due to the flight of higher income earners, pressures from The New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

forced them to offer pensions and other benefits, increasing the average cost of benefits per employee by 1,629 percent. This was in addition to hiring an average of 20 percent more employees to serve the ever shrinking cities. More Americans were driving cars and fewer were using public transportation, and it was not practical to extend to the suburbs. At the same time, the number of surface roads exploded to serve the ever-increasing numbers of individually owned cars, further burdening city and country resources. During this time, the perception of using public transportation turned more negative. In what is arguably the most extreme example, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, the fifth largest city in the United States in 1950 with 1,849,568 residents, had shrunk to 706,585 by 2010, a reduction of 62 percent.

In some instances, the automotive industry and others were directly responsible for the decline of public transportation. The Great American streetcar scandal

The General Motors streetcar conspiracy refers to the convictions of General Motors (GM) and related companies that were involved in the monopolizing of the sale of buses and supplies to National City Lines (NCL) and subsidiaries, as well as to ...

saw GM, Firestone Tire

Firestone Tire and Rubber Company is a tire company founded by Harvey Firestone (1868–1938) in 1900 initially to supply solid rubber side-wire tires for fire apparatus, and later, pneumatic tires for wagons, buggies, and other forms of wheele ...

, Standard Oil of California Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object t ...

, Phillips Petroleum

Phillips Petroleum Company was an American oil company incorporated in 1917 that expanded into petroleum refining, marketing and transportation, natural gas gathering and the chemicals sectors. It was Phillips Petroleum that first found oil in th ...

, Mack Trucks

Mack Trucks, Inc., is an American truck manufacturing company and a former manufacturer of buses and trolley buses. Founded in 1900 as the Mack Brothers Company, it manufactured its first truck in 1905 and adopted its present name in 1922. Mack ...

and other companies purchase a number of streetcars and electric trains in the 1930s and 1940s, such that 90 percent of city trolleys had been dismantled by 1950. It was argued that this was a deliberate destruction of streetcars as part of a larger strategy to push the United States into automobile dependency

Car dependency is the concept that some city layouts cause cars to be favoured over alternate forms of transportation, such as bicycles, public transit, and walking.

Overview

In many modern cities, automobiles are convenient and sometimes nec ...

. In ''United States v. National City Lines, Inc.'', many were found guilty of antitrust violations. The story has been explored several times in print, film and other media, for example in ''Who Framed Roger Rabbit

''Who Framed Roger Rabbit'' is a 1988 American Live-action animated film, live-action/animated comedy film, comedy mystery film directed by Robert Zemeckis, produced by Frank Marshall (filmmaker), Frank Marshall and Robert Watts, and loosely ad ...

'', '' Taken for a Ride'' and ''The End of Suburbia

''The End of Suburbia: Oil Depletion and the Collapse of The American Dream'' is a 2004 documentary film concerning peak oil and its implications for the suburban lifestyle, written and directed by Toronto-based filmmaker Gregory Greene.

Desc ...

''.

Women's rights

The automobile unions played a leading role in advancing the cause ofwomen's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countri ...

. In 1955, the United Auto Workers Union

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, better known as the United Auto Workers (UAW), is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) ...

(UAW) organized the UAW Women's Department to strengthen women's role in the union and encourage participation in the union's elected bodies. In a move that was met with some hostility by Teamsters leaders, the U.S. Division of Transport Personnel had in 1943 instructed Teamsters Union officials that women should be allowed full employment as truck driver

A truck driver (commonly referred to as a trucker, teamster, or driver in the United States and Canada; a truckie in Australia and New Zealand; a HGV driver in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the European Union, a lorry driver, or driver in ...

s. That proved to be only a temporary wartime measure, but a change of heart among Teamsters leadership by the mid-1950s led to the Equal Pay Act of 1963

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 is a United States labor law amending the Fair Labor Standards Act, aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex (see gender pay gap). It was signed into law on June 10, 1963, by John F. Kennedy as part of his New Fro ...

. Women in the auto industry were considered leaders in the movement for women's rights.

Motorsports

Hot rodding

The increasing popularity of hot rodding cars (modifying them to increase performance) is reflected in part by the creation of special-interest magazines catering to this culture. ''Hot Rod

Hot rods are typically American cars that might be old, classic, or modern and that have been rebuilt or modified with large engines optimised for speed and acceleration. One definition is: "a car that's been stripped down, souped up and made ...

'' is the oldest such magazine, with first editor Wally Parks

Wallace Gordon Parks (January 23, 1913 – September 28, 2007) was an American writer. He was the founder, president, and chairman of the National Hot Rod Association, better known as NHRA. He was instrumental in establishing drag racing as a le ...

, and founded by Robert E. Petersen

Robert Einar "Pete" Petersen (September 10, 1926 – March 23, 2007) was an American publisher who founded the Petersen Automotive Museum in 1994.Hevesi, Dennis (March 27, 2007)Robert Petersen, Publisher of Auto Buff Magazines, Dies at 80.''N ...

in 1948, with original publication by his Petersen Publishing Company. ''Hot Rod'' has licensed affiliation with Universal Technical Institute.

The relative abundance and inexpensive nature of the

The relative abundance and inexpensive nature of the Ford Model T

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. The relati ...

and other cars from the 1920s to 1940s helped fuel the hot rod culture that developed, which was focused on getting the most linear speed out of these older automobiles. The origin of the term "hot rod" is unclear, but the culture blossomed in the post-war culture of the 1950s.

''Hot Rod'' magazine's November 1950 cover announced the first hot rod to exceed 200 mph. The hand-crafted car used an Edelbrock-built Mercury flathead V8 and set the record at the Bonneville Salt Flats

The Bonneville Salt Flats are a densely packed salt pan in Tooele County in northwestern Utah. A remnant of the Pleistocene Lake Bonneville, it is the largest of many salt flats west of the Great Salt Lake. It is public land managed by the Bur ...

. This region has been called the "Holy Grail of American Hot Rodding", and is often used for land speed racing Land speed racing is a form of motorsport.

Land speed racing is best known for the efforts to break the absolute land speed record, but it is not limited to specialist vehicles.

A record is defined as the speed over a course of fixed length, avera ...

, a tradition that grew rapidly in the 1950s and continues today.

Hot rodding was about more than raw power. Kustom Kulture started in the 1950s, when artists such as Von Dutch

Von Dutch is an American multinational fashion brand posthumously named after Kenny Howard, a.k.a. "Von Dutch", an American artist and pinstriper of the Kustom Kulture movement. After Howard's death in 1992, his daughters allowed Ed Boswell ...

transformed automobile pin striping from a seldom-used accent that followed the lines of the car into a freestyle art form. Von Dutch was as famous for his "flying eyeball" as he was for his intricate spider-web designs. As the decade began, hand-drawn pin striping was almost unheard of, but by 1958 it had become a popular method of customizing the looks of the hot rod. As the decade progressed, hot rodding became a popular hobby for a growing number of teenagers as the sport literally came to Main Street.

Drag racing

Drag racing

Drag racing is a type of motor racing in which automobiles or motorcycles compete, usually two at a time, to be first to cross a set finish line. The race follows a short, straight course from a standing start over a measured distance, most ...

has existed since the first cars, but it was not until the 1950s that it started to become mainstream, beginning with Santa Ana Drags

Santa Ana Drags was the first drag strip in the United States. The strip was founded by C.J. "Pappy" Hart, Creighton Hunter and Frank Stillwell at the Orange County Airport auxiliary runway in southern California and was operational from June 19 ...

, the first drag strip in the United States. The strip was founded by C. J. "Pappy" Hart, Creighton Hunter and Frank Stillwell at the Orange County Airport auxiliary runway in southern California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, and was operational from 1950 until June 21, 1959.

''Hot Rod'' editor Wally Parks created the National Hot Rod Association

The National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) is a drag racing governing body, which sets rules in drag racing and hosts events all over the United States and Canada. With over 40,000 drivers in its rosters, the NHRA claims to be the largest motorspo ...

in 1951, and it is still the largest governing body in the popular sport. , there are at least 139 professional drag strips operational in the United States. One of the most powerful racing fuels ever developed is nitromethane

Nitromethane, sometimes shortened to simply "nitro", is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is the simplest organic nitro compound. It is a polar liquid commonly used as a solvent in a variety of industrial applications such as in ...

, which dramatically debuted as a racing fuel in 1950, and continues as the primary component used in Top Fuel

Top Fuel is a type of drag racing whose dragsters are the quickest accelerating racing cars in the world and the fastest sanctioned category of drag racing, with the fastest competitors reaching speeds of and finishing the runs in 3.62 seconds ...

drag racing today. While nitromethane had been around for years and was used as an industrial solvent, it was first used as a racing fuel in 1954.

NASCAR

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) is the second most popular spectator sports in the United States behind the

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) is the second most popular spectator sports in the United States behind the National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the majo ...

(NFL). It was incorporated on February 21, 1948, by Bill France, Sr. and built its roots in the 1950s. Two years later in 1950 the first asphalt "superspeedway", Darlington Speedway, was opened in South Carolina, and the sport saw dramatic growth during the 1950s. Because of the tremendous success of Darlington, construction began of a , high-banked superspeedway near Daytona Beach, which is still in use.

The Cup Series

The NASCAR Cup Series is the top racing series of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR). The series began in 1949 as the Strictly Stock Division, and from 1950 to 1970 it was known as the Grand National Division. In 1971, ...

was started in 1949, with Jim Roper winning the first series. By 2008, the most prestigious race in the series, the Daytona 500

The Daytona 500 is a NASCAR Cup Series motor race held annually at Daytona International Speedway in Daytona Beach, Florida. It is the first of two Cup races held every year at Daytona, the second being the Coke Zero Sugar 400, and one of thre ...

had attracted more than 17 million television viewers. Dynasties were born in the 1950s with racers like Lee Petty

Lee Arnold Petty (March 14, 1914 – April 5, 2000) was an American stock car racing driver who competed during the 1950s and 1960s. He was one of the pioneers of NASCAR and one of its first superstars. He was NASCAR's first three-time Cup ch ...

(father of Richard Petty

Richard Lee Petty (born July 2, 1937), nicknamed "The King", is an American former stock car racing driver who raced from 1958 to 1992 in the former NASCAR Grand National and Winston Cup Series (now called the NASCAR Cup Series), most notably ...

, grandfather of Kyle Petty

Kyle Eugene Petty (born June 2, 1960) is an American former stock car racing driver, and current racing commentator. He is the son of racer Richard Petty, grandson of racer Lee Petty, and father of racer Adam Petty, who was killed in a crash d ...

) and Buck Baker

Elzie Wylie Baker Sr. (March 4, 1919 – April 14, 2002), better known as Buck Baker, was an American stock car racer. Born in Richburg, South Carolina, Baker began his NASCAR career in 1949 and won his first race three years later at Columbia ...

(father of Buddy Baker

Elzie Wylie "Buddy" Baker Jr. (January 25, 1941 – August 10, 2015) was an American professional stock car racing driver and commentator. Over the course of his 33-year racing career, he won 19 races in the NASCAR Cup Series, including the 1980 ...

).

NASCAR, and stock car racing in general, has its roots in bootlegging during Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

. Junior Johnson

Robert Glenn Johnson Jr. (June 28, 1931 – December 20, 2019), better known as Junior Johnson, was an American NASCAR driver of the 1950s and 1960s. He won 50 NASCAR races in his career before retiring in 1966. In the 1970s and 1980s, he became ...

was one of many bootleggers who took part in the sport during the 1950s, equally well known for his arrest in 1955 for operating his father's moonshine

Moonshine is high-proof liquor that is usually produced illegally. The name was derived from a tradition of creating the alcohol during the nighttime, thereby avoiding detection. In the first decades of the 21st century, commercial dist ...

still

A still is an apparatus used to distill liquid mixtures by heating to selectively boil and then cooling to condense the vapor. A still uses the same concepts as a basic distillation apparatus, but on a much larger scale. Stills have been use ...

as he is for his racing success. He ended up spending a year in an Ohio prison, but soon returned to the sport before retiring as a driver in 1966.

New business models

Faster food

As more Americans began driving cars, entirely new categories of businesses came into being to allow them to enjoy their products and services without having to leave their cars. This includes the

As more Americans began driving cars, entirely new categories of businesses came into being to allow them to enjoy their products and services without having to leave their cars. This includes the drive-in

A drive-in is a facility (such as a restaurant or movie theater) where one can drive in with an automobile for service. At a drive-in restaurant, for example, customers park their vehicles and are usually served by staff who walk or rollerskat ...

restaurant, and later the drive-through window. Even into the 2010s, the Sonic Drive-In

Sonic Corporation, founded as Sonic Drive-In and more commonly known as Sonic (stylized as SONIC), or "The Drive-In," is an American drive-in fast food restaurant Chain store, chain owned by Inspire Brands, the parent company of Arby's and Buf ...

restaurant chain has provided primarily drive-in service by carhop

A carhop is a waiter or waitress who brings fast food to people in their cars at drive-in restaurants. Carhops usually work on foot but sometimes use roller skates, as depicted in movies such as ''American Graffiti'' and television shows such as ...

in restaurants within 43 U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s, serving approximately 3 million customers per day. Known for its use of carhops on roller skates

Roller skates, are shoes or bindings that fit onto shoes that are worn to enable the wearer to roll along on wheels. The first roller skate was an inline skate design, effectively an ice skate with wheels replacing the blade. Later the "quad s ...

, the company annually hosts a competition to determine the top skating carhop in its system.

A number of other successful "drive up" businesses have their roots in the 1950s, including McDonald's

McDonald's Corporation is an American multinational fast food chain, founded in 1940 as a restaurant operated by Richard and Maurice McDonald, in San Bernardino, California, United States. They rechristened their business as a hambur ...

(expanded c. 1955), which had no dine-in facilities, requiring customers to park and walk up to the window, taking their order "to go". Automation and the lack of dining facilities allowed McDonald's to sell burgers for 15 cents each, instead of the typical 35 cents, and people were buying them by the bagful. By 1948, they had fired their carhops, installed larger grills, reduced their menu and radically changed the industry by introducing assembly-line methods of food production, similar to the auto industry, dubbing it the "Speedee Service System". They redesigned their sign specifically to make it easier to see from the road, creating the now familiar yellow double-arch structure. Businessman Ray Kroc

Raymond Albert Kroc (October 5, 1902 – January 14, 1984) was an American businessman. He purchased the fast food company McDonald's in 1961 and was its CEO from 1967 to 1973. Kroc is credited with the global expansion of McDonald's, turnin ...

joined McDonald's as a franchise agent in 1955. He subsequently purchased the chain from the McDonald brothers and oversaw its worldwide growth.

Other chains were created to serve the increasingly mobile patron. Carl Karcher

Carl Nicholas Karcher SMOM (January 16, 1917 – January 11, 2008) was an American businessman who founded the Carl's Jr. hamburger chain, now owned by parent company Snow Star LP.

Early life

Born on a farm near Upper Sandusky, Ohio, Karcher wa ...

opened his first Carl's Jr. in 1956, and rapidly expanded, locating his restaurants near California's new freeway off-ramps. These restaurant models initially relied on the new and ubiquitous ownership of automobiles, and the willingness of patrons to dine in their automobiles. , drive-through service account for 65 percent of their profits.

Drive-in movies

The drive-in theater is a form ofcinema

Cinema may refer to:

Film

* Cinematography, the art of motion-picture photography

* Film or movie, a series of still images that create the illusion of a moving image

** Film industry, the technological and commercial institutions of filmmaking

...

structure consisting of a large outdoor movie screen, a projection booth, a concession stand

A concession stand (American English, Canadian English), snack kiosk or snack bar (British English, Irish English) is a place where patrons can purchase snacks or food at a cinema, amusement park, zoo, aquarium, circus, fair, stadium, beac ...

and a large parking area

A parking lot (American English) or car park (British English), also known as a car lot, is a cleared area intended for parking vehicles. The term usually refers to an area dedicated only for parking, with a durable or semi-durable surface ...

for automobiles, where patrons view the movie from the comfort of their cars and listen via an electric speaker placed at each parking spot.

Although drive-in movies first appeared in 1933, it was not until well after the post-war era that they became popular, enjoying their greatest success in the 1950s, reaching a peak of more than 4,000 theaters in the United States alone. Drive-in theaters have been romanticized in popular culture with the movie ''

Although drive-in movies first appeared in 1933, it was not until well after the post-war era that they became popular, enjoying their greatest success in the 1950s, reaching a peak of more than 4,000 theaters in the United States alone. Drive-in theaters have been romanticized in popular culture with the movie ''American Graffiti

''American Graffiti'' is a 1973 American coming-of-age comedy-drama film directed by George Lucas, produced by Francis Ford Coppola, written by Willard Huyck, Gloria Katz and Lucas, and starring Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard (billed as Ronny ...

'' and '' Grease'' and the television series ''Happy Days

''Happy Days'' is an American television sitcom that aired first-run on the ABC network from January 15, 1974, to July 19, 1984, with a total of 255 half-hour episodes spanning 11 seasons. Created by Garry Marshall, it was one of the most su ...

''. They developed a reputation for showing B movie

A B movie or B film is a low-budget commercial motion picture. In its original usage, during the Golden Age of Hollywood, the term more precisely identified films intended for distribution as the less-publicized bottom half of a double feature ...

s, typically monster or horror films, and as "passion pits", a place for teenagers to make out

Making out is a term of American origin dating back to at least 1949, and is used to refer to kissing, including extended French kissing or heavy kissing of the neck (called ''necking''), or to acts of non-penetrative sex such as heavy pett ...

. While drive-in theaters are rarer today with only 366 remaining and no longer unique to America, they are still associated as part of the 1950s' American car culture. By the beginning of 2020, the number of fully operational drive-ins has dropped to 20. Drive-in movies have seen somewhat of a resurgence in popularity in the 21st century, due in part to baby boomer

Baby boomers, often shortened to boomers, are the Western demographic cohort following the Silent Generation and preceding Generation X. The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964, during the mid-20th century baby boom. ...

nostalgia, as well as some increased interest during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is a part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In the United States, it has resulted in confir ...

, which forced conventional movie theaters to close..

Robert Schuller

Robert Harold Schuller (September 16, 1926 – April 2, 2015) was an American Christian televangelist, pastor, motivational speaker, and author. In his five decades of television, Schuller was principally known for the weekly ''Hour of Po ...

started the nation's first drive-in church in 1955 in Garden Grove, California

Garden Grove is a city in northern Orange County, California, United States, located just southwest of Disneyland (located in Anaheim, CA). The population was 171,949 at the 2020 census. State Route 22, also known as the Garden Grove Freeway, ...

. After his regular 9:30 am service in the chapel away, he would travel to the drive-in for a second Sunday service. Worshipers listened to his sermon from the comfort of their cars, using the movie theater's speaker boxes.

Malls

The first modern shopping malls were built in the 1950s, such as

The first modern shopping malls were built in the 1950s, such as Bergen Mall

Bergen Town Center (formerly known as The Outlets at Bergen Town Center) is a shopping center located in Bergen County, New Jersey, USA. The center consists of both an indoor mall and exterior outlying stores and occupies over 105 acres split betw ...

, which was the first to use the term "mall" to describe the business model. Other early malls moved retailing away from the dense, commercial downtowns into the largely residential suburbs. Northgate in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

is credited as being the first modern mall design, with two rows of businesses facing each other and a walkway separating them. It opened in 1950. Shopper's World in Framingham, Massachusetts

Framingham () is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The city proper covers with a pop ...

, was the first two-story mall, and opened in 1951. The design was modified again in 1954 when Northland Center in Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

, used a centralized design with an anchor store

In retail, an "anchor tenant", sometimes called an "anchor store", "draw tenant", or "key tenant", is a considerably larger tenant in a shopping mall, often a department store or retail chain. They are typically located at the ends of malls. Wit ...

in the middle of the mall, ringed by other stores. This was the first mall to have the parking lot completely surrounding the shopping center, and to provide central heat and air-conditioning.

In 1956, Southdale Center

Southdale Center is a shopping mall located in Edina, Minnesota, a suburb of the Twin Cities. It opened in 1956 and is both the first and the oldest fully enclosed, climate-controlled shopping mall in the United States. Southdale Center has of le ...

opened in Edina, Minnesota

Edina ( ) is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States and a first-ring suburb of Minneapolis. The population was 53,494 at the 2020 census, making it the 18th most populous city in Minnesota.

Edina began as a small farming and mi ...

. It was the first to combine these modern elements; enclosed with a two-story design, central heat and air-conditioning plus a comfortable common area. It featured two large department stores as anchors. Most industry professionals consider Southdale Center to be the first modern regional mall.

This formula (enclosed space with stores attached, away from downtown and accessible only by automobile) became a popular way to build retail

Retail is the sale of goods and Service (economics), services to consumers, in contrast to wholesaling, which is sale to business or institutional customers. A retailer purchases goods in large quantities from manufacturing, manufacturers, dire ...

across the world. Victor Gruen

Victor David Gruen, born Viktor David Grünbaum

retrieved 25 February 2012 (July 18, 1903 – February 1 ...

, one of the pioneers in mall design, came to abhor this effect of his new design. He decried the creation of enormous "land wasting seas of parking" and the spread of suburban sprawl.

retrieved 25 February 2012 (July 18, 1903 – February 1 ...

Aftermarket auto parts

The 1950s jump started an industry of aftermarket add-ons for cars that continues today. The oldest aftermarket wheel company,American Racing

American Racing Equipment Inc. is a manufacturer of wheels sold via the aftermarket retail sector. Production started during the muscle car era in the United States. Platinum Equity investment group acquired American Racing Equipment Inc in June 2 ...

, started in 1956 and still builds "mag wheels" (alloy wheel

In the automotive industry, alloy wheels are wheels that are made from an alloy of aluminium or magnesium. Alloys are mixtures of a metal and other elements. They generally provide greater strength over pure metals, which are usually much softe ...

s) for almost every car made. Holley introduced the first modular four-barrel carburetor, which Ford offered in the 1957 Ford Thunderbird, and versions are still used by performance enthusiasts. Edelbrock

Edelbrock, LLC is an American manufacturer of specialty automotive and motorcycle parts. The company is headquartered in Olive Branch, Mississippi, with a Southern California R&D Tech Center located in Cerritos, CA. The Edelbrock Sand Cast and ...

started during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and expanded after the war. They provided a variety of high performance parts for the new hot rodders, which was popular equipment for setting speed records at Bonneville Salt Flats. Owners were no longer restricted to the original equipment provided by manufacturers, helping not only create the hot rod culture but also the foundation for cosmetic modifications. The creation and rapid expansion of the aftermarket made it possible for enthusiasts to personalize their automobiles.

Distribution

Most new cars were sold through automobile dealerships in the 1950s, but

Most new cars were sold through automobile dealerships in the 1950s, but Crosley

Crosley was a small, independent American manufacturer of subcompact cars, bordering on microcars. At first called the Crosley Corporation and later Crosley Motors Incorporated, the Cincinnati, Ohio, firm was active from 1939 to 1952, int ...

automobiles were still on sale at any number of appliance or department stores, and Allstate

The Allstate Corporation is an American insurance company, headquartered in Northfield Township, Illinois, near Northbrook since 1967. Founded in 1931 as part of Sears, Roebuck and Co., it was spun off in 1993 but still partially owned by ...

(a rebadged Henry J

The Henry J is an American automobile built by the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation and named after its chairman, Henry J. Kaiser. Production of six-cylinder models began in their Willow Run factory in Michigan on July 1950, and four-cylinder produc ...

) could be ordered at any Sears and Roebuck

Sears, Roebuck and Co. ( ), commonly known as Sears, is an American chain of department stores founded in 1892 by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck and reincorporated in 1906 by Richard Sears and Julius Rosenwald, with what began as ...

in 1952 and 1953. By mid-decade, these outlets had vanished and the automobile dealer became the sole source of new automobiles.

Starting in the mid-1950s, new car introductions in the fall once again became an anticipated event, as all dealers would reveal the models

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

for the upcoming year each October. In this era before the popularization of computerization, the primary source of information on new models was the dealer. The idea was originally suggested in the 1930s by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression, as a way of stimulating the economy by creating demand. The idea was reintroduced by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Dwight Eisenhower for the same reasons, and this method of introducing next year's models in the preceding autumn lasted well into the 1990s.

During the decade, many smaller manufacturers could not compete with the Big Three and either went out of business or merged. In 1954, American Motors

American Motors Corporation (AMC; commonly referred to as American Motors) was an American automobile manufacturing company formed by the merger of Nash-Kelvinator Corporation and Hudson Motor Car Company on May 1, 1954. At the time, it was the ...

was formed when Hudson merged with Nash-Kelvinator Corporation in a deal worth almost $200 million, the largest corporate merger in United States history at that time.

Muscle cars

Themuscle-car

Muscle car is a description according to ''Merriam-Webster Dictionary'' that came to use in 1966 for "a group of American-made two-door sports coupes with powerful engines designed for high-performance driving." The '' Britannica Dictionary'' ...

era is deeply rooted in the 1950s, although there is some debate as to the exact beginning. The 1949 Oldsmobile Rocket 88, created in response to public interest in speed and power, is often cited as the first muscle car. It featured America's first high-compression overhead valve V8 in the smaller, lighter Oldsmobile 76/Chevy body for six-cylinder engines (as opposed to bigger Olds 98 luxury body).Auto editors ofConsumer Guide (16 January 2007). "The Birth of Muscle Cars". musclecars.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 18 January 2016. Dulcich, Steve (August 2007). "Rocket Man". Popular Hot Rodding. Retrieved 18 January 2016. ''Old Cars Weekly'' claims it started with the introduction of the original Chrysler "Firepower" hemi V8 engine in 1951, while others such as ''Hot Rod'' magazine consider the first overhead valve engine by Chevrolet, the 265 cid V8, as the "heir apparent to Ford flathead's position as the staple of racing", in 1955. The " small block Chevy" itself developed its own subculture that exists today. Other contenders include the 1949 Oldsmobile V8 engine

The Oldsmobile V8, also referred to as the Rocket, is series of engines that was produced by Oldsmobile from 1949 until 1990. The Rocket, along with the 1949 Cadillac V8, were the first post-war OHV crossflow cylinder head V8 engines produced b ...

, the first in a long line of such powerful V8 engines, as well as the Cadillac V8 of the same year.

Regardless how it is credited, the horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are t ...

race centered around the V8 engine and the muscle-car era lasted until new smog regulations forced dramatic changes in OEM engine design in the early 1970s. This in turn opened up new opportunities for aftermarket manufacturers like Edelbrock. Each year brought larger engines and/or increases in horsepower, providing a catalyst for customers to upgrade to newer models. Automobile executives also deliberately updated the body designs yearly, in the name of "planned obsolescence" and added newly developed or improved features such as automatic transmissions, power steering, power brakes and cruise control, in an effort to make the previous models seem outdated and facilitate the long drive from the suburbs. Record sales made the decade arguably the "golden era" of automobile manufacturing.

Harley Earl and Bill France Sr. popularized the saying "Race on Sunday, sell on Monday", a mantra still heard today in motorsports, particularly within NASCAR. During the muscle-car era, manufacturers not only sponsored the drivers, but designed stock cars

Stock car racing is a form of automobile racing run on oval tracks and road courses measuring approximately . It originally used production-model cars, hence the name "stock car", but is now run using cars specifically built for racing. It ori ...

specifically to compete in the fast-growing and highly popular sport.

Songs celebrating the automobile

As the automobile became more and more an extension of the individual, it was natural for this to be reflected in popular culture. America's love affair with the automobile was most evident in the music of the era. *"Rocket 88

"Rocket 88" (originally stylized as Rocket "88") is a song that was first recorded in Memphis, Tennessee, in March 1951. The recording was credited to " Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats", who were actually Ike Turner and his Kings of Rhythm. T ...

" was first recorded in 1951 and originally credited to Jackie Brenston

Jackie Brenston (August 24, 1928 or 1930Most published sources and the U.S. Social Security Death Index give 1930 as his year of birth. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and reportedly his gravestone give 1928. – December 15, 1979) ...

and his Delta Cats, although it was later discovered to be the work of Ike Turner

Izear Luster "Ike" Turner Jr. (November 5, 1931 – December 12, 2007) was an American musician, bandleader, songwriter, record producer, and talent scout. An early pioneer of 1950s rock and roll, he is best known for his work in the 1960s and ...

's Kings of Rhythm

The Kings of Rhythm are an American music group formed in the late 1940s in Clarksdale, Mississippi and led by Ike Turner through to his death in 2007. Turner would retain the name of the band throughout his career, although the group has underg ...

. It is often credited as the first rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm ...

song ever produced and has been covered by other artists.

*"Hot Rod Lincoln

"Hot Rod Lincoln" is a song by American singer-songwriter Charlie Ryan, first released in 1955. It was written as an answer song to Arkie Shibley's 1950 hit " Hot Rod Race" (US #29).

It describes a drive north on US Route 99 (predecessor t ...

" was first recorded in 1955 by Charlie Ryan, and has since been recorded by Roger Miller

Roger Dean Miller Sr. (January 2, 1936 – October 25, 1992) was an American singer-songwriter, widely known for his honky-tonk-influenced novelty songs and his chart-topping country and pop hits " King of the Road", " Dang Me", and "Eng ...

and others. The 1960 Johnny Bond

Cyrus Whitfield Bond (June 1, 1915 – June 12, 1978), known professionally as Johnny Bond, was an American country music singer-songwriter, guitarist and composer and publisher, who co-founded a music publishing firm, he was active in the musi ...

version charted at number 26 on Billboard Hot 100. Comedian Jim Varney

James Albert Varney Jr. (June 15, 1949 – February 10, 2000) was an American actor and comedian. He is best known for his broadly comedic role as Ernest P. Worrell, for which he won a Daytime Emmy Award, as well as appearing in films and n ...

produced a version with Ricky Skaggs

Rickie Lee Skaggs (born July 18, 1954), known professionally as Ricky Skaggs, is an American neotraditional country and bluegrass singer, musician, producer, and composer. He primarily plays mandolin; however, he also plays fiddle, guitar, ...

for the motion picture ''The Beverly Hillbillies

''The Beverly Hillbillies'' is an American television sitcom that was broadcast on CBS from 1962 to 1971. It had an ensemble cast featuring Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer Jr. as the Clampetts, a poor, backwoods family f ...

''. The song is still a popular live song for artists such as Asleep at the Wheel

Asleep at the Wheel is an American Western swing group that was formed in Paw Paw, West Virginia, and is based in Austin, Texas. The band has won nine Grammy Awards since their 1970 inception, released over twenty albums, and has charted more ...

and Junior Brown

Jamieson "Junior" Brown (born June 12, 1952) is an American country guitarist and singer. He has released twelve studio albums in his career, and has charted twice on the ''Billboard'' country singles charts. Brown's signature instrument is t ...

.

*" Maybellene", released by Chuck Berry

Charles Edward Anderson Berry (October 18, 1926 – March 18, 2017) was an American singer, songwriter and guitarist who pioneered rock and roll. Nicknamed the " Father of Rock and Roll", he refined and developed rhythm and blues into th ...

in 1955, is an uptempo rocker describing a hot rod race between a jilted lover and his unfaithful girlfriend. It was a #5 hit and was described by ''Rolling Stone

''Rolling Stone'' is an American monthly magazine that focuses on music, politics, and popular culture. It was founded in San Francisco, California, in 1967 by Jann Wenner, and the music critic Ralph J. Gleason. It was first known for its ...

'' as the starting point of rock and roll guitar.

*"Wake Up Little Susie

"Wake Up Little Susie" is a popular song written by Felice and Boudleaux Bryant and published in 1957.

The song is best known in a recording by the Everly Brothers, issued by Cadence Records as catalog number 1337. The Everly Brothers record ...

" recorded by The Everly Brothers

The Everly Brothers were an American rock duo, known for steel-string acoustic guitar playing and close harmony singing. Consisting of Isaac Donald "Don" Everly (February 1, 1937 – August 21, 2021) and Phillip "Phil" Everly (January 19, 193 ...

, reached number one on the ''Billboard

A billboard (also called a hoarding in the UK and many other parts of the world) is a large outdoor advertising structure (a billing board), typically found in high-traffic areas such as alongside busy roads. Billboards present large adverti ...

'' Pop chart, despite having been banned

A ban is a formal or informal prohibition of something. Bans are formed for the prohibition of activities within a certain political territory. Some bans in commerce are referred to as embargoes. ''Ban'' is also used as a verb similar in meaning ...

from Boston radio stations for lyrics about elaborating "our reputation is shot" because the narrator and his date slept through a drive-through movie date and missed their curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

by six hours.

*" Teen Angel" was released in 1959 and initially met with resistance by radio stations because of its dark message about a young girl who dies in an automobile/train accident.

Other songs recorded during the decade also reflect the automobile's place in American culture, such as "Brand New Cadillac

"Brand New Cadillac" (also recorded as "Cadillac") is a 1959 song by Vince Taylor, and was originally released as a B-side. Featured musicians on the released recording were: Joe Moretti (guitars), Lou Brian (piano), Brian Locking (bass) and B ...

", Sonny Burgess

Albert Austin "Sonny" Burgess (May 28, 1929 – August 18, 2017) was an American rockabilly guitarist and singer.

Biography

Burgess was born on a farm near Newport, Arkansas to Albert and Esta Burgess. He graduated from Newport High School in 1 ...

's "Thunderbird" and Bo Diddley

Ellas McDaniel (born Ellas Otha Bates; December 30, 1928 – June 2, 2008), known professionally as Bo Diddley, was an American guitarist who played a key role in the transition from the blues to rock and roll. He influenced many artists, inc ...

's "Cadillac". A 1955 Oldsmobile was celebrated in the nostalgic " Ol' '55" by Tom Waits

Thomas Alan Waits (born December 7, 1949) is an American musician, composer, songwriter, and actor. His lyrics often focus on the underbelly of society and are delivered in his trademark deep, gravelly voice. He worked primarily in jazz during ...

(1973).

See also

*American automobile industry in the 1950s

The 1950s were pivotal for the American automobile industry. The post-World War II era brought a wide range of new technologies to the automobile consumer, and a host of problems for the independent automobile manufacturers. The industry was mat ...

*Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952 authorized $550 million for the Interstate Highway System on a 50–50 matching basis, meaning the federal government paid 50% of the cost of building and maintaining the interstate while each individual sta ...

*List of car crash songs

The car crash song emerged as a popular pop and rock music teenage tragedy song during the 1950s and 1960s at a time when the number of people being killed in vehicle collisions was rising rapidly in many countries. In the United Kingdom, the ...

*List of defunct automobile manufacturers of the United States

This is a list of defunct automobile manufacturers of the United States. They were discontinued for various reasons, such as bankruptcy of the parent company, mergers, or being phased out.

A

* A Automobile Company (1910–1913) 'Blue & Gold' ...

* History of the automobile

*Timeline of motor vehicle brands

This is a chronological index for the start year for motor vehicle brands (up to 1969). For manufacturers that went on to produce many models, it represents the start date of the whole brand; for the others, it usually represents the date of appea ...

* Cruising

*Elvis' Pink Cadillac

Elvis Presley's iconic Pink Cadillac was a 1955 Cadillac Fleetwood Cadillac Sixty Special, Sixty Special. It set style for the era, was sung about in popular culture, and was copied by others around the world.

The car is now preserved in the Grac ...

* General Motors Motorama

*Raggare

Raggare is a subculture found mostly in Sweden and parts of Norway and Finland, and to a lesser extent in Denmark, Germany, and Austria. Raggare are related to the American greaser and rockabilly subcultures and are known for their lov ...

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * {{refendExternal links

''Hot Rod'' magazine covers from the 1950s

History of the automobile American culture 1950s cars Society of the United States American studies Automotive industry in the United States 1950s in the United States Car culture