The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last

imperial dynasty, the

Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

-led

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

, and led to the establishment of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

. The revolution was the culmination of a decade of agitation, revolts, and uprisings. Its success marked the collapse of the

Chinese monarchy, the end of 2,132 years of imperial rule in China and 276 years of the Qing dynasty, and the beginning of China's

early republican era.

[Li, Xiaobing. ]007

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

(2007). ''A History of the Modern Chinese Army''. University Press of Kentucky. , . pp. 13, 26–27.

The Qing dynasty had struggled for a long time to reform the government and resist foreign aggression, but the

program of reforms after 1900 was opposed by conservatives in the Qing court as too radical and by reformers as too slow. Several factions, including underground

anti-Qing groups, revolutionaries in exile, reformers who wanted to save the monarchy by modernizing it, and activists across the country debated how or whether to overthrow the Qing dynasty. The flash-point came on 10 October 1911, with the

Wuchang Uprising, an armed rebellion among members of the

New Army

The New Armies ( Traditional Chinese: 新軍, Simplified Chinese: 新军; Pinyin: Xīnjūn, Manchu: ''Ice cooha''), more fully called the Newly Created Army ( ''Xinjian Lujun''Also translated as "Newly Established Army" ()), was the modernised ...

. Similar revolts then broke out spontaneously around the country, and revolutionaries in all provinces of the country renounced the Qing dynasty. On 1 November 1911, the Qing court appointed

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

(leader of the powerful

Beiyang Army

The Beiyang Army (), named after the Beiyang region,Hong Zhang (2019)"Yuan Shikai and the Significance of his Troop Training at Xiaozhan, Tianjin, 1895–1899" ''The Chinese Historical Review'' 26(1) was a large, Western-style Imperial Chinese Ar ...

) as Prime Minister, and he began negotiations with the revolutionaries.

In Nanjing, revolutionary forces created a

provisional coalition government. On 1 January 1912, the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

declared the establishment of the Republic of China, with

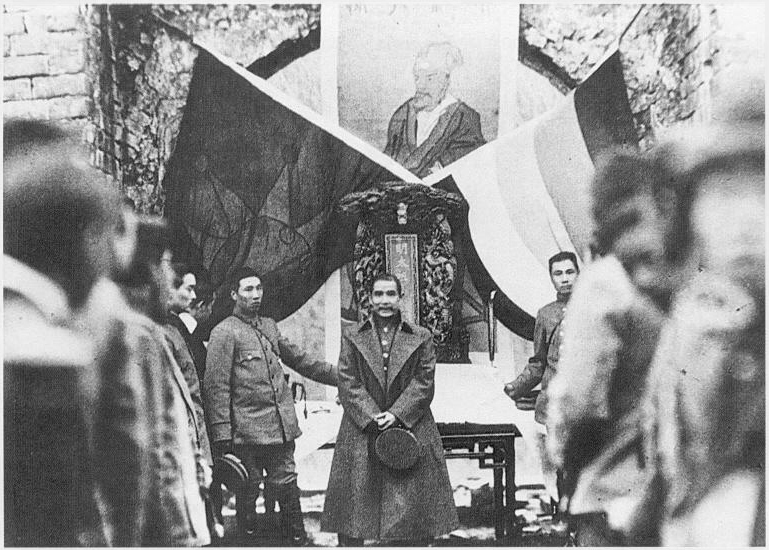

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, leader of the

Tongmenghui (United League), as

President of the Republic. A brief civil war between the North and the South ended in compromise. Sun would resign in favor of Yuan Shikai, who would become President of the

new national government, if Yuan could secure the abdication of the Qing emperor. The

edict of abdication of the last

Chinese emperor

''Huangdi'' (), translated into English as Emperor, was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial regimes in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was considered the Son of Heave ...

, the six-year-old

Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

, was promulgated on 12 February 1912. Yuan was sworn in as president on 10 March 1912. Yuan's failure to consolidate a legitimate central government before his death in 1916, led to decades of

political division and warlordism, including an

attempt at imperial restoration.

The revolution is named Xinhai because it occurred in 1911, the year of the Xinhai () stem-branch in the

sexagenary cycle

The sexagenary cycle, also known as the Stems-and-Branches or ganzhi ( zh, 干支, gānzhī), is a cycle of sixty terms, each corresponding to one year, thus a total of sixty years for one cycle, historically used for recording time in China and t ...

of the traditional

Chinese calendar

The traditional Chinese calendar (also known as the Agricultural Calendar ��曆; 农历; ''Nónglì''; 'farming calendar' Former Calendar ��曆; 旧历; ''Jiùlì'' Traditional Calendar ��曆; 老历; ''Lǎolì'', is a lunisolar calendar ...

. The

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

on the

island of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is an island country located in East Asia. The main island of Taiwan, formerly known in the Western political circles, press and literature as Formosa, makes up 99% of the land area of the territor ...

and the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

on the

Chinese mainland both consider themselves the legitimate successors to the 1911 Revolution and honor the ideals of the revolution including

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

,

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

,

modernization

Modernization theory is used to explain the process of modernization within societies. The "classical" theories of modernization of the 1950s and 1960s drew on sociological analyses of Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim and a partial reading of Max Weber, ...

of China and

national unity

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: T ...

. In Taiwan, 10 October is commemorated as

Double Ten Day

The National Day of the Republic of China ( zh, 中華民國的國慶日) or the Taiwan National Day, also referred to as Double Ten Day or Double Tenth Day, is a public holiday on 10 October, now held annually in Taiwan (officially the Republi ...

, the National Day of the Republic of China. In mainland China, the day is celebrated as the Anniversary of the 1911 Revolution.

Background

After suffering its first defeat by the West in the

First Opium War

The First Opium War (), also known as the Opium War or the Anglo-Sino War was a series of military engagements fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of the ...

in 1842, a conservative court culture constrained efforts to reform and did not want to cede authority to local officials. Following defeat in the

Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire#Britain's imperial ...

in 1860, the Qing began efforts to modernize by adopting Western technologies through the

Self-Strengthening Movement

The Self-Strengthening Movement, also known as the Westernization or Western Affairs Movement (–1895), was a period of radical institutional reforms initiated in China during the late Qing dynasty following the military disasters of the Opium ...

. In the wars against the

Taiping (1851–64),

Nian (1851–68),

Yunnan (1856–73) and

the Northwest (1862–77), the court came to rely on armies raised by local officials.

[Wang, Ke-wen. 998(1998). ''Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism''. Taylor & Francis publishing. , . p. 106. p. 344.] After a generation of relative success in importing Western naval and weapons technology, defeat in the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the p ...

in 1895 was all the more humiliating and convinced many of the need for institutional change.

[Bevir, Mark. ]010 010 may refer to:

* 10 (number)

* 8 (number) in octal numeral notation

* Motorola 68010, a microprocessor released by Motorola in 1982

* 010, the telephone area code of Beijing

* 010, the Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the R ...

(2010). ''Encyclopedia of Political Theory''. Sage Publishing. , . p. 168. The court established the

New Army

The New Armies ( Traditional Chinese: 新軍, Simplified Chinese: 新军; Pinyin: Xīnjūn, Manchu: ''Ice cooha''), more fully called the Newly Created Army ( ''Xinjian Lujun''Also translated as "Newly Established Army" ()), was the modernised ...

under

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

and many concluded that Chinese society also needed to be modernized if technological and commercial advancements were to succeed.

In 1898, the

Guangxu Emperor

The Guangxu Emperor (14 August 1871 – 14 November 1908), personal name Zaitian, was the tenth Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign lasted from 1875 to 1908, but in practice he ruled, w ...

turned to reformers like

Kang Youwei

Kang Youwei (; Cantonese: ''Hōng Yáuh-wàih''; 19March 185831March 1927) was a prominent political thinker and reformer in China of the late Qing dynasty. His increasing closeness to and influence over the young Guangxu Emperor spar ...

and

Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啓超 ; Wade-Giles: ''Liang2 Chʻi3-chʻao1''; Yale: ''Lèuhng Kái-chīu'') (February 23, 1873 – January 19, 1929) was a Chinese politician, social and political activist, journalist, and intellectual. His thou ...

who offered a program inspired in large part by the

reforms in Japan. They proposed basic reform in education, military, and economy in the so-called

Hundred Days' Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu E ...

.

The reform was abruptly canceled by a

conservative coup led by

Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; mnc, Tsysi taiheo; formerly romanised as Empress Dowager T'zu-hsi; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908), of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan, was a Chinese noblewoman, concubine and later regent who effectively controlled ...

. The Emperor was put under house arrest in June 1898, where he remained until his death in 1908.

Reformers Kang and Liang exiled themselves to avoid being executed. The Empress Dowager controlled policy until her death in 1908, with support from officials such as Yuan. Attacks on foreigners and Chinese Christians in the

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

, encouraged by the Empress Dowager, prompted another foreign invasion of Beijing in 1900.

After the Allies imposed a

punitive settlement, the Qing court carried out basic fiscal and administrative reforms, including local and provincial elections. These moves did not secure trust or wide support among political activists. Many, like

Zou Rong, felt strong

anti-Manchu prejudice and blamed them for China's troubles. Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao formed the

Emperor Protection Society in an attempt to restore the emperor,

but others, such as

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

organized revolutionary groups to overthrow the dynasty rather than reform it. They could operate only in secret societies and underground organizations, in foreign concessions, or exile overseas, but created a following among

Chinese in North America and Southeast Asia, and within China, even in the new armies. The

famine in 1906 and 1907 was also a major contributor to the revolution. After the death of the Empress Dowager and the Emperor in 1908, conservative Manchu elements in the court opposed reform and provoked support for revolutionaries.

Organization of the Revolution

Earliest groups

Many revolutionaries and groups wanted to overthrow the Qing government to re-establish the Han-led government. The earliest revolutionary organizations were founded outside of China, such as

Yeung Ku-wan's

Furen Literary Society, created in Hong Kong in 1890. There were 15 members, including

Tse Tsan-tai

Tse Tsan-tai (; 16 May 1872 – 4 April 1938), courtesy name Sing-on (), art-named Hong-yu (), was an Australian Chinese revolutionary, active during the late Qing dynasty. Tse had an interest in designing airships but none were ever construct ...

, who did political satire such as "The Situation in the Far East", one of the first-ever Chinese

manhua

() are Chinese-language comics produced in China and Taiwan. Whilst Chinese comics and narrated illustrations have existed in China in some shape or form throughout its imperial history, the term first appeared in 1904 in a comic titled ''Cu ...

, and who later became one of the core founders of the ''

South China Morning Post

The ''South China Morning Post'' (''SCMP''), with its Sunday edition, the ''Sunday Morning Post'', is a Hong Kong-based English-language newspaper owned by Alibaba Group. Founded in 1903 by Tse Tsan-tai and Alfred Cunningham, it has remained ...

''.

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

's

Xingzhonghui (Revive China Society) was established in

Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the isla ...

in 1894 with the main purpose of raising funds for revolutions. The two organizations merged in 1894.

Smaller groups

The

Huaxinghui (China Revival Society) was founded in 1904 by notables like

Huang Xing

Huang Xing or Huang Hsing (; 25 October 1874 – 31 October 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and politician, and the first commander-in-chief of the Republic of China. As one of the founders of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Republic o ...

,

Zhang Shizhao,

Chen Tianhua , Sun Yat-sen, and

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren (, ; Given name at birth: Liàn 鍊; Courtesy name: Dùnchū 鈍初) (5 April 1882 – 22 March 1913) was a Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuomintang (KMT). Song Jiaoren led the KMT to elec ...

, along with 100 others. Their motto was "Take one province by force, and inspire the other provinces to rise".

The

Guangfuhui (Restoration Society) was also founded in 1904, in Shanghai, by

Cai Yuanpei. Other notable members include

Zhang Binglin and Tao Chengzhang. Despite professing the anti-Qing cause, the Guangfuhui was highly critical of Sun Yat-sen.

[Wang, Ke-wen. 998(1998). ''Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism''. Taylor & Francis Publishing. , . p.287.] One of the most famous female revolutionaries was

Qiu Jin

Qiu Jin (; 8 November 1875 – 15 July 1907) was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist, and writer. Her courtesy names are Xuanqing () and Jingxiong (). Her sobriquet name is Jianhu Nüxia (). Qiu was executed after a failed uprising against the Qi ...

, who fought for

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countri ...

and was also from Guangfuhui.

There were also many other minor revolutionary organizations, such as Lizhi Xuehui (勵志學會) in

Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

, Gongqianghui (公強會) in

Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

, Yiwenhui (益聞會) and Hanzudulihui (漢族獨立會) in

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

, Yizhishe (易知社) in

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

, Yuewanghui (岳王會) in

Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

and Qunzhihui (群智會/群智社) in Guangzhou.

Criminal organizations also existed that were anti-Manchu, including the

Green Gang

The Green Gang () was a Chinese secret society and criminal organization, which was prominent in criminal, social and political activity in Shanghai during the early to mid 20th century.

History

Origins

As a secret society, the origins and hist ...

and

Hongmen

The Tiandihui, the Heaven and Earth Society, also called Hongmen (the Vast Family), is a Chinese fraternal organization and historically a secretive folk religious sect in the vein of the Ming loyalist White Lotus Sect, the Tiandihui's ...

Zhigongtang (致公堂). Sun Yat-sen himself came in contact with the Hongmen, also known as

Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth society).

Gelaohui (Elder Brother Society) was another group, with

Zhu De

Zhu De (; ; also Chu Teh; 1 December 1886 – 6 July 1976) was a Chinese general, military strategist, politician and revolutionary in the Chinese Communist Party. Born into poverty in 1886 in Sichuan, he was adopted by a wealthy uncle at ...

,

Wu Yuzhang, Liu Zhidan (劉志丹) and

He Long. This revolutionary group would eventually develop a strong link with the later

Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

.

Tongmenghui

Sun Yat-sen successfully united the Revive China Society, Huaxinghui and Guangfuhui in the summer of 1905, thereby establishing the unified

Tongmenghui (United League) in August 1905 in Tokyo.

While it started in Tokyo, it had loose organizations distributed across and outside the country. Sun Yat-sen was the leader of this unified group. Other revolutionaries who worked with the Tongmenghui include

Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

and

Hu Hanmin. When the Tongmenhui was established, more than 90% of the Tongmenhui members were between 17 and 26 years of age. Some of the work in the era includes manhua publications such as the ''

Journal of Current Pictorial''.

Later groups

In February 1906, Rizhihui (日知會) also had many revolutionaries, including Sun Wu (孫武), Zhang Nanxian (張難先), He Jiwei and Feng Mumin. A nucleus of attendees at this conference evolved into the Tongmenhui's establishment in Hubei.

In July 1907, several members of Tongmenhui in Tokyo advocated a revolution in the area of the

Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

. Liu Quiyi (劉揆一), Jiao Dafeng (焦達峰), Zhang Boxiang (張伯祥) and Sun Wu (孫武) established Gongjinhui (Progressive Association) (共進會).

[Wang, Ke-wen. 998(1998). ''Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism''. Taylor & Francis Publishing. , . pp. 390–391.] In January 1911, the revolutionary group Zhengwu Xueshe (振武學社) was renamed as Wenxueshe (Literary Society) (文學社).

[張豈之, 陳振江, 江沛. 002(2002). 晚淸民國史. Volume 5 of 中國歷史, 張 豈之. 五南圖書出版股份有限公司. , . pp. 178–186] Jiang Yiwu (蔣翊武) was chosen as the leader. These two organizations would play a big role in the Wuchang Uprising.

Many young revolutionaries adopted the

anarchist program. In Tokyo,

Liu Shipei proposed to overthrow the Manchus and return to Chinese classical values. In Paris, well-connected young intellectuals,

Li Shizhen

Li Shizhen (July 3, 1518 – 1593), courtesy name Dongbi, was a Chinese acupuncturist, herbalist, naturalist, pharmacologist, physician, and writer of the Ming dynasty. He is the author of a 27-year work, found in the ''Compendium o ...

,

Wu Zhihui and

Zhang Renjie

Zhang Renjie (Chang Jen-chieh 19 September 1877 − 3 September 1950), born Zhang Jingjiang, was a political figure and financial entrepreneur in the Republic of China. He studied and worked in France in the early 1900s, where he became an early ...

, agreed with Sun's revolutionary program and joined the Tongmenghui, but argued that simply replacing one government with another would not be progress; fundamental cultural change, a revolution in family, gender and social values, would remove the need for government and coercion.

Zhang Ji Zhang Ji may refer to:

* Zhang Ji (Han dynasty) (張濟) (died 196), official under the warlord Dong Zhuo

* Zhang Zhongjing (150–219), formal name Zhang Ji (張機), Han dynasty physician

* Zhang Ji (Derong) (張既) (died 223), general of Cao Wei ...

and

Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

were among the anarchists who defended assassination and terrorism as means to awaken the people to revolution, but others insisted that education was the only justifiable strategy. Important anarchists included

Cai Yuanpei. Zhang Renjie gave Sun major financial help. Many of these anarchists would later assume high positions in the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

(KMT).

Views

Many revolutionaries promoted anti-Qing/anti-Manchu sentiments and revived memories of conflict between the ethnic minority

Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

and the ethnic majority

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

from the late

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

(1368–1644). Leading intellectuals were influenced by books that had survived from the final years of the Ming dynasty, the last dynasty of Han Chinese. In 1904, Sun Yat-sen announced that his organization's goal was "to expel the

Tatar barbarians, to revive

Zhonghua

Zhōnghuá, Chung¹-hua² or Chunghwa is a term that means "''China''" or "''relating to China''" (), in a cultural, ethnic, or literary sense. It is used in the following terms:

People's Republic of China

* ', the Chinese name for the People' ...

, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people." (驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權).

[計秋楓, 朱慶葆. 001(2001). 中國近代史, V. 1. Chinese University Press. , . p. 468.] Many underground groups promoted the ideas of "Resist Qing and restore Ming" (反清復明) that had been around since the days of the

Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a massive rebellion and civil war that was waged in China between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It last ...

. Others, such as

Zhang Binglin, supported straight-up lines like "slay the Manchus" and concepts like "Anti-Manchuism" (興漢滅胡 / 排滿主義).

Strata and groups

Many groups supported the 1911 Revolution, including students and intellectuals returning from abroad, as well as participants of revolutionary organizations, overseas Chinese, soldiers of the new army, local gentry, farmers, and others.

Overseas Chinese

Assistance from

overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese () refers to people of Chinese birth or ethnicity who reside outside Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese.

Terminology

() or ''Hoan-kheh'' () in Hokkien, ref ...

was important in the 1911 Revolution. In 1894, the first year of the Revive China Society, the first meeting ever held by the group was held in the home of Ho Fon, an overseas Chinese who was the leader of the first Chinese Church of Christ. Overseas Chinese supported and actively participated in funding revolutionary activities, especially the Southeast Asian Chinese of

Malaya (Singapore and

Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

).

[Gao, James Zheng. 009(2009). ''Historical Dictionary of Modern China'' (1800–1949). Issue 25 of "Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civilizations and Historical Eras". Scarecrow Press. , . p.156. p.29.] Many of these groups were reorganized by Sun, who was referred to as the "father of the Chinese revolution".

Newly-Emerged intellectuals

The Qing government established new schools and encouraged students to study abroad as part of the

Self-Strengthening movement

The Self-Strengthening Movement, also known as the Westernization or Western Affairs Movement (–1895), was a period of radical institutional reforms initiated in China during the late Qing dynasty following the military disasters of the Opium ...

. Many young people attended the new schools or went abroad to study in places like Japan.

[Fenby, Jonathan. 008(2008). ''The History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power''. . p. 96. p. 106.] A new progressive class of intellectuals emerged from those students, who contributed immensely to the 1911 Revolution. Besides Sun Yat-sen, key figures in the revolution, such as Huang Xing,

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren (, ; Given name at birth: Liàn 鍊; Courtesy name: Dùnchū 鈍初) (5 April 1882 – 22 March 1913) was a Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuomintang (KMT). Song Jiaoren led the KMT to elec ...

,

Hu Hanmin,

Liao Zhongkai

Liao Zhongkai (April 23, 1877 – August 20, 1925) was a Chinese-American Kuomintang leader and financier. He was the principal architect of the first Kuomintang–Chinese Communist Party (KMT–CCP) United Front in the 1920s. He was assassina ...

,

Zhu Zhixin Zhu Zhixin is the name of:

*Zhu Zhixin (revolutionary) (1885–1920), Tongmenghui revolutionary and writer

*Zhu Zhixin (politician) (born 1949), People's Republic of China politician and economic official

{{hndis ...

and Wang Jingwei, were all Chinese students in Japan. Some were young students like

Zou Rong, known for writing ''Revolutionary Army'', a book in which he talked about the extermination of the Manchus for the 260 years of oppression, sorrow, cruelty, and tyranny, and turning the

sons and grandsons of Yellow Emperor into

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

s.

[Fenby, Jonathan. 008(2008). ''The History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power''. . p. 109.]

Before 1908, revolutionaries focused on coordinating these organizations in preparation for uprisings they would launch; hence, these groups would provide most of the manpower needed for the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty. After the 1911 Revolution, Sun Yat-sen recalled the days of recruiting support for the revolution and said, "The literati were deeply into the search for honors and profits, so they were regarded as having only secondary importance. By contrast, organizations like

Sanhehui were able to sow widely the ideas of resisting the Qing and restoring the Ming."

Gentry and businessmen

The gentry's strength in local politics became apparent. From December 1908, the Qing government created some apparatus to allow the gentry and businessmen to participate in politics. These middle-class people were originally supporters of constitutionalism. However, they became disenchanted when the Qing government created a

cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

with

Prince Qing

Prince Qing of the First Rank (Manchu: ; ''hošoi fengšen cin wang''), or simply Prince Qing, was the title of a princely peerage used in China during the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1636–1912). It was also one of the 12 "iron-cap" princely pe ...

as

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

. By early 1911, an experimental cabinet had thirteen members, nine of whom were Manchus selected from the imperial family.

[Wang, Ke-wen. 998(1998). ''Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism''. Taylor & Francis Publishing. , . p. 76.]

Foreign supporters

Besides Chinese and overseas Chinese, some supporters and participants of the 1911 Revolution were foreigners; among them, the Japanese were the most active group. Some Japanese even became members of Tongmenghui.

Miyazaki Touten was the closest Japanese supporter; others included Heiyama Shu and

Ryōhei Uchida.

Homer Lea

Homer Lea (November 17, 1876 – November 1, 1912) was an American adventurer, author and geopolitical strategist. He is today best known for his involvement with Chinese reform and revolutionary movements in the early twentieth century and as ...

, an American, who became Sun Yat-sen's closest foreign advisor in 1910, supported Sun Yat-sen's military ambitions.

British soldier Rowland J. Mulkern also took part in the revolution.

[Lau, Kit-ching Chan. ]990

Year 990 ( CMXC) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* Al-Mansur, ''de facto'' ruler of Al-Andalus, conquers the Castle of Montemor-o-Velho (mode ...

(1990). ''China, Britain and Hong Kong, 1895–1945''. Chinese University Press. , . p.37. Some foreigners, such as English explorer

Arthur de Carle Sowerby

Arthur de Carle Sowerby (8 July 1885 – 16 August 1954; ) was a British naturalist, explorer, writer, and publisher in China. His father was Arthur Sowerby (15 October 1857 – 27 June 1934; ).

Background

Arthur Sowerby was the son of a Chri ...

, led expeditions to rescue foreign missionaries in 1911 and 1912.

The far right-wing Japanese ultra-nationalist

Black Dragon Society supported Sun Yat-sen's activities against the Manchus, believing that overthrowing the Qing would help the Japanese take over the Manchu homeland and that Han Chinese would not oppose the takeover. Toyama believed that the Japanese could easily take over Manchuria and that Sun Yat-sen and other anti-Qing revolutionaries would not resist and help the Japanese take over and enlarge the opium trade in China, while the Qing was trying to destroy the opium trade. The Japanese Black Dragons supported Sun Yat-sen and anti-Manchu revolutionaries until the Qing collapsed.

The far right-wing Japanese ultranationalist

Gen'yōsha

The was an influential Pan-Asianist group and secret society active in the Empire of Japan, and was considered to be an ultranationalist group by General Headquarters in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

Foundation as the ...

leader

Tōyama Mitsuru

was a Japanese right wing and ultranationalist founder of Genyosha ('' Black Ocean Society'') and Kokuryukai (''Black Dragon Society''). Tōyama was a strong advocate of Pan Asianism (Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere).

Early life

Tōyam ...

supported anti-Manchu, anti-Qing revolutionary activities including the ones organized by Sun Yat-sen and supported Japanese taking over Manchuria. The anti-Qing

Tongmenghui was founded and based in exile in Japan where many anti-Qing revolutionaries gathered.

The Japanese had been trying to unite anti-Manchu groups made out of Han people to take down the Qing. The Japanese were the ones who helped Sun Yat-sen unite all anti-Qing, anti-Manchu revolutionary groups together, and there were Japanese like

Tōten Miyazaki

or Torazō Miyazaki (1 January 1871 – 6 December 1922) was a Japanese philosopher who aided and supported Sun Yat-sen during the Xinhai Revolution. While Sun was in Japan, he assisted Sun in his travels as he was wanted by Qing dynasty autho ...

inside of the anti-Manchu Tongmenghui revolutionary alliance. The Black Dragon Society hosted the Tongmenghui in its first meeting.

The Black Dragon Society had very intimate, long term and influential relations with Sun Yat-sen who sometimes passed himself off as Japanese.

According to an American military historian, Japanese military officers were part of the Black Dragon Society. The Yakuza and Black Dragon Society helped arrange in Tokyo for Sun Yat-sen to hold the first Kuomintang meetings, and were hoping to flood China with opium and overthrow the Qing and deceive the Chinese into overthrowing the Qing to Japan's benefit. After the revolution was successful, the Japanese Black Dragons started infiltrating China and spreading opium. The Black Dragons pushed for the takeover of Manchuria by Japan in 1932.

Sun Yat-sen was married to a Japanese,

Kaoru Otsuki.

Soldiers of the New Armies

The

New Army

The New Armies ( Traditional Chinese: 新軍, Simplified Chinese: 新军; Pinyin: Xīnjūn, Manchu: ''Ice cooha''), more fully called the Newly Created Army ( ''Xinjian Lujun''Also translated as "Newly Established Army" ()), was the modernised ...

was formed in 1901 after the defeat of the Qings in the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the p ...

.

They were launched by a decree from eight provinces.

New Army troops were by far the best trained and equipped.

Recruits were of a higher quality than the old army and received regular promotions.

Beginning in 1908, the revolutionaries began to shift their call to the new armies. Sun Yat-sen and the revolutionaries infiltrated the New Army.

Uprisings and incidents

The central foci of the uprisings were mostly connected with the

Tongmenghui and Sun Yat-sen, including subgroups. Some uprisings involved groups that never merged with the Tongmenghui. Sun Yat-sen may have participated in 8–10 uprisings; all uprisings failed before the Wuchang Uprising.

First Guangzhou Uprising

In the spring of 1895, the

Revive China Society, based in Hong Kong, planned the First Guangzhou Uprising (廣州起義).

Lu Haodong was tasked with designing the revolutionaries'

Blue Sky with a White Sun

The Blue Sky with a White Sun () serves as the design for the party flag and emblem of the Kuomintang, the canton of the flag of the Republic of China, the national emblem of the Republic of China, and as the naval jack of the ROC Navy.

In th ...

flag.

On 26 October 1895,

Yeung Ku-wan and Sun Yat-sen led

Zheng Shiliang Zheng may refer to:

*Zheng (surname), Chinese surname (鄭, 郑, ''Zhèng'')

*Zheng County, former name of Zhengzhou, capital of Henan, China

*Guzheng (), a Chinese zither with bridges

*Qin Shi Huang (259 BC – 210 BC), emperor of the Qin Dynasty, ...

and Lu Haodong to Guangzhou, preparing to capture Guangzhou in one strike. However, the details of their plans were leaked to the Qing government.

[計秋楓, 朱慶葆. 001(2001). 中國近代史, Volume 1. Chinese University Press. , . p.464.] The government began to arrest revolutionaries, including Lu Haodong, who was later executed.

The First Guangzhou Uprising was a failure. Under pressure from the Qing government, the government of Hong Kong banned the two men from the territory for five years. Sun Yat-sen went into exile, promoting the Chinese revolution and raising funds in Japan, the United States, Canada, and Britain. In 1901, following the Huizhou Uprising, Yeung Ku-wan was assassinated by Qing agents in Hong Kong.

[South China Morning Post. 6 April 2011. Waiting may be over at the grave of an unsung hero.] After his death, his family protected his identity by not putting his name on his tomb, just a number: 6348.

Independence Army Uprising

In 1900, after the

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

started, Tang Caichang (唐才常) and

Tan Sitong of the previous

Foot Emancipation Society The Foot Emancipation Society (), or Anti-footbinding Society (; ''Jiè chánzú huì''), was a civil organization which opposed foot binding in late Qing dynasty China. It was affected by the Hundred Days' Reform of 1898, and this organization adv ...

organized the Independence Army. The Independence Army Uprising (自立軍起義) was planned to occur on 23 August 1900.

[Wang, Ke-wen. 998(1998). ''Modern China: an encyclopedia of history, culture, and nationalism''. Taylor & Francis Publishing. , . p.424.] Their goal was to overthrow

Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; mnc, Tsysi taiheo; formerly romanised as Empress Dowager T'zu-hsi; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908), of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan, was a Chinese noblewoman, concubine and later regent who effectively controlled ...

to establish a constitutional monarchy under the Guangxu Emperor. Their plot was discovered by the governors-general of Hunan and Hubei. About twenty conspirators were arrested and executed.

Huizhou Uprising

On 8 October 1900, Sun Yat-sen ordered the launch of the

Huizhou

Huizhou ( zh, c= ) is a city in central-east Guangdong Province, China, forty-three miles north of Hong Kong. Huizhou borders the provincial capital of Guangzhou to the west, Shenzhen and Dongguan to the southwest, Shaoguan to the north, Heyu ...

Uprising (惠州起義). The revolutionary army was led by Zheng Shiliang and initially included 20,000 men, who fought for half a month. However, after the

Japanese Prime Minister prohibited Sun Yat-sen from carrying out revolutionary activities on Taiwan, Zheng Shiliang had no choice but to order the army to disperse. Accordingly, this uprising also failed. British soldier Rowland J. Mulkern participated in this uprising.

Great Ming Uprising

A very short uprising occurred from 25 to 28 January 1903, to establish a "Great Ming Heavenly Kingdom" (大明順天國). This involved

Tse Tsan-tai

Tse Tsan-tai (; 16 May 1872 – 4 April 1938), courtesy name Sing-on (), art-named Hong-yu (), was an Australian Chinese revolutionary, active during the late Qing dynasty. Tse had an interest in designing airships but none were ever construct ...

, Li Jitang (李紀堂), Liang Muguang (梁慕光) and Hong Quanfu (洪全福), who formerly took part in the

Jintian uprising during the

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom era.

Ping-liu-li Uprising

Ma Fuyi (馬福益) and

Huaxinghui was involved in an uprising in the three areas of

Pingxiang,

Liuyang and

Liling, called "Ping-liu-li Uprising", (萍瀏醴起義) in 1905.

[Joan Judge. ]996

Year 996 ( CMXCVI) was a leap year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Japan

* February - Chotoku Incident: Fujiwara no Korechika and Takaie shoot an arrow at Retired Emp ...

(1996). Print and politics: 'Shibao' and the culture of reform in late Qing China. Stanford University Press. , . p. 214. The uprising recruited miners as early as 1903 to rise against the Qing ruling class. After the uprising failed, Ma Fuyi was executed.

Beijing Zhengyangmen East Railway assassination attempt

Wu Yue (吳樾) of

Guangfuhui carried out an assassination attempt at the Beijing Zhengyangmen East Railway station (正陽門車站) in an attack on five Qing officials on 24 September 1905.

Huanggang Uprising

The Huanggang Uprising (黃岡起義) was launched on 22 May 1907, in

Chaozhou

Chaozhou (), alternatively Chiuchow, Chaochow or Teochew, is a city in the eastern Guangdong province of China. It borders Shantou to the south, Jieyang to the southwest, Meizhou to the northwest, the province of Fujian to the east, and th ...

.

[張家鳳. ]010 010 may refer to:

* 10 (number)

* 8 (number) in octal numeral notation

* Motorola 68010, a microprocessor released by Motorola in 1982

* 010, the telephone area code of Beijing

* 010, the Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the R ...

(2010). 中山先生與國際人士. Volume 1. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司. , . p. 195. The revolutionary party, along with Xu Xueqiu (許雪秋), Chen Yongpo (陳湧波) and Yu Tongshi (余通實), launched the uprising and captured Huanggang city.

Other Japanese that followed include 萱野長知 and 池亨吉.

After the uprising began, the Qing government quickly and forcefully suppressed it. Around 200 revolutionaries were killed.

Huizhou Qinühu Uprising

In the same year, Sun Yat-sen sent more revolutionaries to

Huizhou

Huizhou ( zh, c= ) is a city in central-east Guangdong Province, China, forty-three miles north of Hong Kong. Huizhou borders the provincial capital of Guangzhou to the west, Shenzhen and Dongguan to the southwest, Shaoguan to the north, Heyu ...

to launch the "Huizhou Qinühu Uprising" ().

[. 002(2002). . Volume 5 of . publishing. , . p.177.] On 2 June, Deng Zhiyu () and Chen Chuan () gathered some followers, and together they seized Qing arms in the lake, from Huizhou.

[. 002(2002). , 1901–2000, Volume 1. .] They killed several Qing soldiers and attacked Taiwei () on 5 June.

The Qing army fled in disorder, and the revolutionaries exploited the opportunity, capturing several towns. They defeated the Qing army once again in Bazhiyie. Many organizations voiced their support after the uprising, and the number of revolutionary forces increased to two hundred men at its height. The uprising, however, ultimately failed.

Anqing Uprising

On 6 July 1907,

Xu Xilin of

Guangfuhui led an uprising in

Anqing

Anqing (, also Nganking, formerly Hwaining, now the name of Huaining County) is a prefecture-level city in the southwest of Anhui province, People's Republic of China. Its population was 4,165,284 as of the 2020 census, with 804,493 living in the ...

, Anhui, which became known as the Anqing Uprising (安慶起義).

Xu Xilin at the time was the police commissioner as well as the supervisor of the police academy. He led an uprising that aimed to assassinate the provincial governor of Anhui, En Ming (恩銘).

[Lu Xun. Nadolny, Kevin John. 009(2009). Capturing Chinese: Short Stories from Lu Xun's Nahan. Capturing Chinese publishing. , . p.51.] They were defeated after four hours of fighting. Xu was captured, and En Ming's bodyguards cut out his heart and liver and ate them.

His cousin

Qiu Jin

Qiu Jin (; 8 November 1875 – 15 July 1907) was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist, and writer. Her courtesy names are Xuanqing () and Jingxiong (). Her sobriquet name is Jianhu Nüxia (). Qiu was executed after a failed uprising against the Qi ...

was executed a few days later.

Qinzhou Uprising

From August to September 1907, the

Qinzhou Uprising occurred (欽州防城起義), to protest against heavy taxation from the government. Sun Yat-sen sent Wang Heshun (王和順) there to assist the revolutionary army and captured the county in September.

[辛亥革命武昌起義紀念館. ]991

Year 991 ( CMXCI) was a common year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

* March 1: In Rouen, Pope John XV ratifies the first Truce of God, between Æthelred the Unready and Richard I of ...

(1991). 辛亥革命史地圖集. 中國地圖出版社 publishing. After that, they attempted to besiege and capture Qinzhou but were unsuccessful. They eventually retreated to the area of Shiwandashan, while Wang Heshun returned to

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

.

Zhennanguan Uprising

On 1 December 1907, the Zhennanguan Uprising (鎮南關起事) took place at

Zhennanguan along the Chinese-Vietnamese border. Sun Yat-sen sent Huang Mintang (黃明堂) to monitor the pass, which was guarded by a fort.

With the assistance of supporters among the fort's defenders, the revolutionaries captured the cannon tower in Zhennanguan. Sun Yat-sen,

Huang Xing

Huang Xing or Huang Hsing (; 25 October 1874 – 31 October 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and politician, and the first commander-in-chief of the Republic of China. As one of the founders of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Republic o ...

and

Hu Hanmin personally went to the tower to command the battle. The Qing government sent troops led by

Long Jiguang

Long Jiguang (龍濟光) (1867–1925) was an ethnic Hani Chinese general of the late Qing and early Republican period of China.

Biography

Long's older brother Jinguang (龍覲光) was also a general. Long began his military career suppressin ...

and

Lu Rongting

Lu Rongting (; September 9, 1859 – November 6, 1928), also spelled as Lu Yung-ting and Lu Jung-t'ing, was a late Qing/early Republican military and political leader from Wuming, Guangxi. Lu belonged to the Zhuang ethnic group.吴振汉. � ...

to counterattack, and the revolutionaries were forced to retreat into the mountainous areas. After this uprising's failure, Sun was forced to move to Singapore due to

anti-Sun sentiments within the revolutionary groups. He would not return to the mainland until after the Wuchang Uprising.

Qin-lian Uprising

On 27 March 1908, Huang Xing launched a raid, later known as the Qin-lian Uprising (欽廉上思起義), from a base in Vietnam and attacked the cities of

Qinzhou and

Lianzhou in Guangdong. The struggle continued for fourteen days but was forced to stop after the revolutionaries ran out of supplies.

Hekou Uprising

In April 1908, another uprising was launched in

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

, Hekou, called the Hekou Uprising (雲南河口起義). Huang Mingtang (黃明堂) led two hundred men from Vietnam and attacked Hekou on 30 April. Other participating revolutionaries included Wang Heshun (王和順) and Guan Renfu (關仁甫). They were outnumbered and defeated by government troops, however, and the uprising failed.

Mapaoying Uprising

On 19 November 1908, the Mapaoying Uprising (馬炮營起義) was launched by revolutionary group Yuewanghui (岳王會) member Xiong Chenggei (熊成基) at

Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

. Yuewanghui, at this time, was a subset of

Tongmenghui. This uprising also failed.

Gengxu New Army Uprising

In February 1910, the Gengxu New Army Uprising (庚戌新軍起義), also known as the Guangzhou New Army Uprising (廣州新軍起義), took place.

[张新民. 993(1993). 中国人权辞书. 海南出版社 publishing. Digitized by University of Michigan. 9 October 2009.] This involved a conflict between the citizens and local police against the New Army. After revolutionary leader Ni Yingdian was killed by Qing forces, the remaining revolutionaries were quickly defeated, causing the uprising to fail.

Second Guangzhou Uprising

On 27 April 1911, an uprising occurred in Guangzhou, known as the Second Guangzhou Uprising (辛亥廣州起義) or Yellow Flower Mound Revolt (黃花岡之役). It ended in disaster, as 86 bodies were found (only 72 could be identified).

[王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. . p. 195-198.] The 72 revolutionaries were remembered as

martyrs

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

.

Revolutionary

Lin Juemin (林覺民) was one of the 72. On the eve of battle, he wrote "A Letter to My Wife" (與妻訣別書), later to be considered a masterpiece in Chinese literature.

[Langmead, Donald. 011(2011). ''Maya Lin: A Biography''. ABC-CLIO Publishing. , . pp. 5–6.]

Wuchang Uprising

The Literary Society (文學社) and the Progressive Association (共進會) were revolutionary organizations involved in the uprising that mainly began with a

Railway Protection Movement protest.

In the late summer, some Hubei New Army units were ordered to neighboring Sichuan to quell the Railway Protection Movement, a mass protest against the Qing government's seizure and handover of local railway development ventures to foreign powers.

[Reilly, Thomas. ]997

Year 997 ( CMXCVII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Japan

* 1 February: Empress Teishi gives birth to Princess Shushi - she is the first child of the ...

(1997). ''Science and Football III'', Volume 3. Taylor & Francis publishing. , . pp. 105–106, 277–278. Banner

A banner can be a flag or another piece of cloth bearing a symbol, logo, slogan or another message. A flag whose design is the same as the shield in a coat of arms (but usually in a square or rectangular shape) is called a banner of arms. Als ...

officers like

Duanfang, the railroad superintendent, and

Zhao Erfeng

Zhao Erfeng (1845–1911), courtesy name Jihe, was a late Qing Dynasty official and Han Chinese bannerman, who belonged to the Plain Blue Banner. He was an assistant amban in Tibet at Chamdo in Kham (eastern Tibet). He was appointed in March ...

led the New Army against the Railway Protection Movement.

The New Army units of Hubei had originally been the Hubei Army, which had been trained by Qing official

Zhang Zhidong

Zhang Zhidong () (4 September 18375 October 1909) was a Chinese politician who lived during the late Qing dynasty. Along with Zeng Guofan, Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang, Zhang Zhidong was one of the four most famous officials of the late Qing ...

.

On 24 September, the Literary Society and Progressive Association convened a conference in Wuchang, along with sixty representatives from local New Army units. During the conference, they established a headquarters for the uprising. The leaders of the two organizations, Jiang Yiwu (蔣翊武) and Sun Wu (孫武), were elected as commander and chief of staff. Initially, the date of the uprising was to be 6 October 1911.

[王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 6 民國. 中華書局. . pp. 3–7.] It was postponed to a later date due to insufficient preparations.

Revolutionaries intent on overthrowing the Qing dynasty had built bombs, and on 9 October, one accidentally exploded.

Sun Yat-sen himself had no direct part in the uprising and was traveling in the United States at the time to recruit more support from among overseas Chinese. The Qing

Viceroy of Huguang

The Viceroy of Huguang, fully referred to in Chinese as the Governor-General of Hubei and Hunan Provinces and the Surrounding Areas; Overseeing Military Affairs, Food Production; Director of Civil Affairs, was one of eight regional Viceroys in C ...

, Rui Cheng (瑞澂), tried to track down and arrest the revolutionaries.

[戴逸, 龔書鐸. 002(2003) 中國通史. 清. Intelligence Press. . pp. 86–89.] Squad leader Xiong Bingkun (熊秉坤) and others decided not to delay the uprising any longer and launched the revolt on 10 October 1911, at 7:00 p.m.

The revolt was a success; the entire city of Wuchang was captured by the revolutionaries on the morning of 11 October. That evening, they established a tactical headquarters and announced the establishment of the "Military Government of Hubei of Republic of China".

The conference chose

Li Yuanhong

Li Yuanhong (; courtesy name Songqing 宋卿) (October 19, 1864 – June 3, 1928) was a Chinese politician during the Qing dynasty and the Republic of China. He was the president of the Republic of China between 1916 and 1917, and between 1922 ...

as the governor of the temporary government.

Qing officers like the bannermen Duanfang and Zhao Erfeng were killed by the revolutionary forces.

Revolutionaries killed a German arms dealer in Hankou as he was delivering arms to the Qing. Revolutionaries killed 2 Germans and wounded 2 other Germans at the battle of Hanyang, including a former colonel.

Provincial uprisings

After the success of the Wuchang Uprising, many other protests occurred throughout the country for various reasons. Some uprisings declared restoration (光復) of the

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

rule. Other uprisings were a step toward independence, and some were protests or rebellions against the local authorities. Regardless of the reason for the uprising the outcome was that all provinces in the country renounced the Qing dynasty and joined the ROC.

Changsha Restoration

On 22 October 1911, the

Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

Tongmenghui were led by Jiao Dafeng (焦達嶧) and Chen Zuoxin (陳作新).

[张创新. 005(2005). 中国政治制度史. 2nd Edition. Tsinghua University Press. , . p.377.] They headed an armed group, consisting partly of revolutionaries from

Hongjiang

Hongjiang (), formerly Qianyang County () is a county-level city in Hunan Province, China, it is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Huaihua.

Located on the southwest of the province and the south of Huaihua, the city is ...

and partly of defecting New Army units, in a campaign to extend the uprising into

Changsha

Changsha (; ; ; Changshanese pronunciation: (), Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is the capital and the largest city of Hunan Province of China. Changsha is the 17th most populous city in China with a population of over 10 million, and ...

.

They captured the city and killed the local Imperial general. Then they announced the establishment of the Hunan Military Government of the Republic of China and announced their opposition to the Qing Empire.

Shaanxi Uprising

On the same day,

Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

's Tongmenghui, led by Jing Dingcheng (景定成) and Qian Ding (錢鼎) as well as Jing Wumu (井勿幕) and others including

Gelaohui, launched an uprising and captured

Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

after two days of struggle.

The Hui Muslim community was divided in its support for the revolution. The Hui Muslims of Shaanxi supported the revolutionaries, while the Hui Muslims of Gansu supported the Qing. The native Hui Muslims (Mohammedans) of Xi'an (Shaanxi province) joined the Han Chinese revolutionaries in slaughtering the Manchus. The native Hui Muslims of Gansu province led by general

Ma Anliang led more than twenty battalions of

Hui Muslim troops to defend the Qing imperials and attacked Shaanxi, held by revolutionary Zhang Fenghui (張鳳翽).

The attack was successful, and after news arrived that Puyi was about to abdicate, Ma agreed to join the new Republic.

The revolutionaries established the "Qinlong Fuhan Military Government" and elected Zhang Fenghui, a member of the Yuanrizhi Society (原日知會), as new governor.

After the Xi'an Manchu quarter fell on 24 October, Xinhai forces killed all the Manchus in the city, about 20,000 Manchus were killed in the massacre.

[Rhoads, Edward J. M. 000(2000). ''Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928''. University of Washington Publishing. , . p.192.] Many of its Manchu defenders committed suicide, including Qing general Wenrui (文瑞), who threw himself down a well.

Only some wealthy Manchus who were ransomed and Manchu females survived. Wealthy Han Chinese seized Manchu girls to become their slaves and poor Han Chinese troops seized young Manchu women to be their wives. Young Manchu girls were also seized by Hui Muslims of Xi'an during the massacre and brought up as Muslims.

Hui General Ma Anliang abandoned the Qing cause upon the Qing abdication in the Xinhai Revolution while the Manchu governor general Shengyun was enraged at the revolution.

Pro-revolution Hui Muslims like Shaanxi Governor Ma Yugui and Beijing Imam Wang Kuan persuaded Qing Hui general Ma Anliang to stop fighting, telling him as Muslims not to kill each other for the sake of the Qing monarchists and side with the republican revolutionaries instead. Ma Anliang then agreed to abandon the Qing under the combination of Yuan Shikai's actions and these messages from other Hui.

A year before the massacre of Manchus in October 1911, an oath against Manchus was sworn at the

Great Goose Pagoda in Xi'an by the Gelaohui in 1911. Manchu banner garrisons were slaughtered in Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Taiyuan, Xi'an and Wuchang The Manchu quarter was located in the north eastern part of Xi'an and walled off while the Hui Muslim quarter was located in the northwestern part of Xi'an but did not have walls separating it from the Han parts. Southern Xi'an was entirely Han. Xi'an had the biggest Manchu banner garrison quarter by area before its destruction.

The revolutionaries were led by students of the military academy who overcame the guards at the gates of Xi'an and shut them, secured the arsenal and slaughtering all Manchus at their temple and then storming and slaughtering the Manchus in the Manchu banner quarter of the city. The Manchu quarter was set on fire and many Manchus were burned alive. Manchu men, women and girls were slaughtered for three days and then after that, only Manchu women and girls were spared while Manchu men and boys continued to be slaughtered. Many Manchus committed suicide by overdosing on opium and throwing themselves into wells. The revolutionaries were helped by the fact that Manchus stored gunpowder in their houses so they exploded when set on fire, killing the Manchus inside. 10,000 to 20,000 Manchus were slaughtered.

Ma Anliang was ordered to attack the revolutionaries in Shaanxi by the

baoyi bondservant Chang Geng and Manchu Shengyun.

Eastern soldiers of the new republic were mobilized by Yuan Shikai when the attack against Shaanxi began by Ma Anliang, but news of the abdication of the Qing emperor reached Ma Anliang before he attacked Xi'an, so Ma Anliang ended all military operations and changed his allegiance to the Republic of China. All pro-Qing military activity in the northwest was put to an end by this.

Yuan Shikai managed to induce Ma Anliang to not attack Shaanxi after the Gelaohui took over the province and accept the Republic of China under his presidency in 1912. During the National Protection war in 1916 between republicans and Yuan Shikai's monarchy, Ma Anliang readied his soldiers and informed the republicans that he and the Muslims would stick to Yuan Shikai until the end. Yuan Shikai ordered Ma Anliang to block Bai Lang (White Wolf) from going into Sichuan and Gansu by blocking Hanzhong and Fengxiangfu.

The Protestant Shensi mission operated a hospital in Xian. Some American missionaries were reported killed in Xi'an. A report claimed Manchus massacred missionaries in the suburbs of Xi'an. Missionaries were reported killed in Xi'an and Taiyuan. Shaanxi joined the revolution on October 24. Sheng Yun was governor of Shaanxi in 1905.

Jiujiang Uprising

On 23 October,

Lin Sen

Lin Sen (; 16 March 1868 – 1 August 1943), courtesy name Tze-chao (子超), sobriquet Chang-jen (長仁), was a Chinese politician who served as Chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China from 1931 until his death.

Early li ...

, Jiang Qun (蔣群), Cai Hui (蔡蕙) and other members of the Tongmenghui in the province of

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

plotted a revolt of New Army units.

[伍立杨. 011(2011). 中国1911 (辛亥年). , . Chapter 连锁反应 各省独立.] After they achieved victory, they announced their independence. The Jiujiang Military Government was then established.

Shanxi Taiyuan Uprising

On 29 October,

Yan Xishan of the New Army led an uprising in

Taiyuan

Taiyuan (; ; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ; also known as (), ()) is the capital and largest city of Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China. Taiyuan is the political, economic, cultural and international exchange center of Shanxi Province. ...

, the capital city of the province of

Shanxi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-leve ...

, along with Yao Yijie (姚以價), Huang Guoliang (黃國梁), Wen Shouquan (溫壽泉), Li Chenglin (李成林), Zhang Shuzhi (張樹幟) and Qiao Xi (喬煦).

The rebels in Taiyuan bombarded the streets where Banner people resided and killed all the Manchu. They managed to kill the Qing Governor of Shanxi, Lu Zhongqi (陸鍾琦). They then announced the establishment of Shanxi Military Government with Yan Xishan as the military governor.

Yan Xishan would later become one of the warlords that plagued China during what was known as "the warlord era".

Kunming Double Ninth Uprising

On 30 October, Li Genyuan (李根源) of the Tongmenghui in

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

joined with

Cai E

Cai E (; 18 December 1882 – 8 November 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and general. He was born Cai Genyin () in Shaoyang, Hunan, and his courtesy name was Songpo (). Cai eventually became an influential warlord in Yunnan ( Yu ...

, Luo Peijin (羅佩金),

Tang Jiyao

Tang Jiyao () (August 14, 1883 – May 23, 1927) was a Chinese general and warlord of Yunnan during the Warlord Era of early Republican China. He was military governor of Yunnan from 1913-27.

Life

Tang was born in Huize county in 1883 in ...

, and other officers of the New Army to launch the

Double Ninth Uprising (重九起義). They captured

Kunming

Kunming (; ), also known as Yunnan-Fu, is the capital and largest city of Yunnan province, China. It is the political, economic, communications and cultural centre of the province as well as the seat of the provincial government. The headquar ...

the next day and established the Yunnan Military Government, electing

Cai E

Cai E (; 18 December 1882 – 8 November 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and general. He was born Cai Genyin () in Shaoyang, Hunan, and his courtesy name was Songpo (). Cai eventually became an influential warlord in Yunnan ( Yu ...

as the military governor.

Nanchang Restoration

On 31 October, the

Nanchang

Nanchang (, ; ) is the capital of Jiangxi Province, People's Republic of China. Located in the north-central part of the province and in the hinterland of Poyang Lake Plain, it is bounded on the west by the Jiuling Mountains, and on the east ...

branch of the Tongmenghui led New Army units in a successful uprising. They established the Jiangxi Military Government.

was elected as the military governor.

Li declared

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

as independent and launched an expedition against Qing official Yuan Shikai.

Shanghai Armed Uprising

On 3 November, Shanghai's Tongmenghui, Guangfuhui and merchants led by

Chen Qimei (陳其美), Li Pingsu (李平書), Zhang Chengyou (張承槱), Li Yingshi (李英石), Li Xiehe (李燮和) and

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren (, ; Given name at birth: Liàn 鍊; Courtesy name: Dùnchū 鈍初) (5 April 1882 – 22 March 1913) was a Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuomintang (KMT). Song Jiaoren led the KMT to elec ...

organized an armed rebellion in Shanghai.

They received support from local police officers.

The rebels captured the Jiangnan Workshop on the 4th and captured Shanghai soon after. On 8 November, they established the Shanghai Military Government and elected Chen Qimei as the military governor.

He would eventually become one of the founders of the

ROC four big families, along with some of the most well-known families of the era.

Guizhou Uprising

On 4 November, Zhang Bailin (張百麟) of the revolutionary party in

Guizhou

Guizhou (; Postal romanization, formerly Kweichow) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in the Southwest China, southwest region of the China, People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Guiyang, in the center of the pr ...

led an uprising along with New Army units and students from the military academy. They immediately captured

Guiyang

Guiyang (; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ), historically rendered as Kweiyang, is the capital of Guizhou province of the People's Republic of China. It is located in the center of the province, situated on the east of the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, ...

and established the Great Han Guizhou Military Government, electing Yang Jincheng (楊藎誠) and Zhao Dequan (趙德全) as the chief and vice governor respectively.

Zhejiang Uprising

Also on 4 November, revolutionaries in

Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

urged the New Army units in

Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

to launch an uprising.

Zhu Rui (朱瑞), Wu Siyu (吳思豫), Lu Gongwang (吕公望) and others of the New Army captured the military supplies workshop.

Other units, led by

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

and Yin Zhirei (尹銳志), captured most of the government offices.

Eventually, Hangzhou was under the control of the revolutionaries, and the constitutionalist Tang Shouqian (湯壽潛) was elected as the military governor.

Jiangsu Restoration

On 5 November,

Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

constitutionalists and gentry urged Qing governor Cheng Dequan (程德全) to announce independence and established the Jiangsu Revolutionary Military Government with Cheng himself as the governor.

Unlike some other cities, anti-Manchu violence began after the restoration on 7 November in

Zhenjiang

Zhenjiang, alternately romanized as Chinkiang, is a prefecture-level city in Jiangsu Province, China. It lies on the southern bank of the Yangtze River near its intersection with the Grand Canal. It is opposite Yangzhou (to its north) a ...

.

[Rhoads, Edward J.M. 000(2000). ''Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928''. University of Washington Press. , . p. 194.] Qing general Zaimu (載穆) agreed to surrender, but because of a misunderstanding, the revolutionaries were unaware that their safety was guaranteed.

The Manchu quarters were ransacked, and an unknown number of Manchus were killed.

Zaimu, feeling betrayed, committed suicide.

This is regarded as the Zhenjiang Uprising (鎮江起義).

Anhui Uprising

Members of

Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

's Tongmenghui also launched an uprising on that day and laid siege to the provincial capital. The constitutionalists persuaded

Zhu Jiabao

Zhu Jiabao (; 1860 – September 5, 1923) was a Chinese monarchist politician who supported the creation of the Empire of China and the 1917 Manchu Restoration of Zhang Xun. He was born in Ningzhou Town, Huaning County, Yunnan. In 1907, he ...

(朱家寶), the Qing Governor of Anhui, to announce independence.

Guangxi Uprising

On 7 November, the

Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

politics department decided to secede from the Qing government, announcing Guangxi's independence. Qing Governor Shen Bingkun (沈秉堃) was allowed to remain governor, but

Lu Rongting

Lu Rongting (; September 9, 1859 – November 6, 1928), also spelled as Lu Yung-ting and Lu Jung-t'ing, was a late Qing/early Republican military and political leader from Wuming, Guangxi. Lu belonged to the Zhuang ethnic group.吴振汉. � ...

would soon become the new governor.

Lu Rongting would later rise to prominence during the "warlord era" as one of the warlords, and his bandits controlled Guangxi for more than a decade. Under leadership of

Huang Shaohong

Huang Shaohong (1895 – August 31, 1966) was a warlord in Guangxi province and governed Guangxi as part of the New Guangxi Clique through the latter part of the Warlord era, and a leader in later years of the Republic of China.

Biography

...

, the Muslim law student

Bai Chongxi

Bai Chongxi (18 March 1893 – 2 December 1966; , , Xiao'erjing: ) was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader. He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Musli ...

was enlisted into a Dare to Die unit to fight as a revolutionary.

Fujian Independence

In November, members of

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

's branch of the Tongmenghui, along with Sun Daoren (孫道仁) of the New Army, launched an uprising against the Qing army.

[国祁李. ]990

Year 990 ( CMXC) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe