17th Lancers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was a

The 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was a

In 1759, Colonel John Hale of the

In 1759, Colonel John Hale of the

Led by Lt Col Samuel Birch, the regiment was sent to

Led by Lt Col Samuel Birch, the regiment was sent to

In December 1857 the regiment arrived in India to reinforce the effort to suppress the

In December 1857 the regiment arrived in India to reinforce the effort to suppress the  The regiment was sent to

The regiment was sent to

In February 1900 a contingent from the regiment, comprising Lieutenant-Colonel E. F. Herbert and 500 troops, was deployed to

In February 1900 a contingent from the regiment, comprising Lieutenant-Colonel E. F. Herbert and 500 troops, was deployed to

The regiment, which was based in

The regiment, which was based in

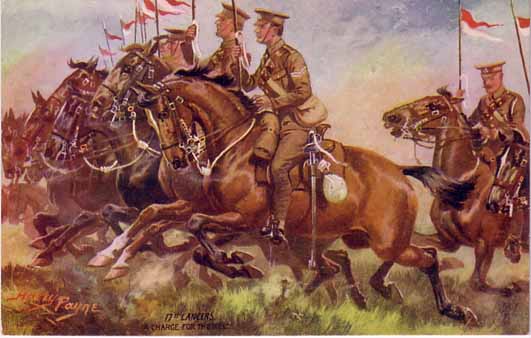

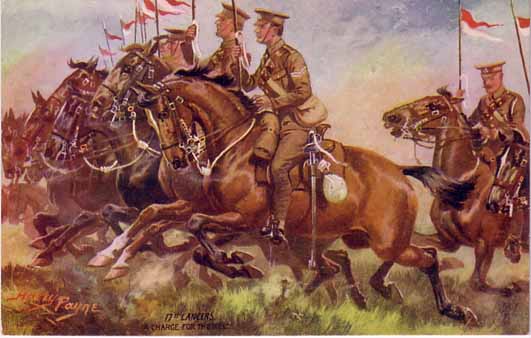

The 17th Lancers

{{British Cavalry Regiments World War I 17 Lancers Military units and formations established in 1759 Military units and formations disestablished in 1922 L17 Regiments of the British Army in the Crimean War Regiments of the British Army in the American Revolutionary War 1759 establishments in Great Britain

The 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was a

The 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was a cavalry regiment

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating a ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

, raised in 1759 and notable for its participation in the Charge of the Light Brigade

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a failed military action involving the British light cavalry led by Lord Cardigan against Russian forces during the Battle of Balaclava on 25 October 1854 in the Crimean War. Lord Raglan had intended to ...

during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

. The regiment was amalgamated with the 21st Lancers to form the 17th/21st Lancers in 1922.

History

Seven Years War

In 1759, Colonel John Hale of the

In 1759, Colonel John Hale of the 47th Foot

The 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in Scotland in 1741. It served in North America during the Seven Years' War and American Revolutionary War and also fought during the Napoleonic Wars ...

was ordered back to Britain with General James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 ŌĆō 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. ...

's final dispatches and news of his victory in the Battle of Quebec in September 1759. After his return, he was rewarded with land in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and granted permission to raise a regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

of light dragoons

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

. He formed the regiment in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

on 7 November 1759 as the 18th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons, which also went by the name of Hale's Light Horse.Frederick, p. 36 The admiration of his men for General Wolfe was evident in the cap badge Colonel Hale chose for the regiment: the Death's Head

Death's Head is the name of several fictional characters appearing in British comics and American comic books both published by Marvel Comics.

The original DeathŌĆÖs Head is a robotic bounty hunter (or rather, as he calls himself, a "freelance ...

with the motto "Or Glory".

The regiment saw service in Germany in 1761 and was renumbered the 17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons in April 1763 In 1764 the regiment went to Ireland. In May 1766 it was renumbered again, this time as the 3rd Regiment of Light Dragoons. It regained the 17th numeral in 1769 as the 17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons.

American Revolution

Led by Lt Col Samuel Birch, the regiment was sent to

Led by Lt Col Samuel Birch, the regiment was sent to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

in 1775, arriving in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, then besieged by American rebels in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 ŌĆō September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.Cannon, p. 15 It fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in ...

, a costly British victory, in June 1775. The regiment was withdrawn to Halifax.Cannon, p. 16 It fought at the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yor ...

in August 1776 at the Battle of White Plains

The Battle of White Plains was a battle in the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War, fought on October 28, 1776 near White Plains, New York. Following the retreat of George Washington's Continental Army northward f ...

in October 1776Cannon, p. 18 and at the Battle of Fort Washington

The Battle of Fort Washington was fought in New York on November 16, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War between the United States and Great Britain. It was a British victory that gained the surrender of the remnant of the garrison of ...

in November 1776. It was in action again at the Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery in October 1777, the Battle of Crooked Billet in May 1778Cannon, p. 22 and the Battle of Barren Hill

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

later that month.

The regiment provided a detachment for operations in the southern colonies as part of Tarleton's Legion, a mixture of infantry and cavalry, and was engaged in a number of battles. The legion, commanded by Banastre Tarleton

Sir Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet, GCB (21 August 175415 January 1833) was a British general and politician. He is best known as the lieutenant colonel leading the British Legion at the end of the American Revolution. He later served in Portu ...

, was founded in 1778 by Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British C ...

contingents from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

, and New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. As the attached regular cavalry, the 17th Light Dragoons clung on to an identity separate from the provincials, even refusing to exchange their fading scarlet clothing for the legion's green jackets. They sustained heavy losses in the Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was an engagement during the American Revolutionary War fought on January 17, 1781 near the town of Cowpens, South Carolina, between U.S. forces under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan and Kingdom of Great Britain, British for ...

in January 1781 after being ordered by Tarleton to charge a formation of American militia. Although their charge was initially effective, the dragoons, numbering about 50, were quickly surprised and outnumbered by concealed American cavalry, under Colonel William Washington

William Washington (February 28, 1752 ŌĆō March 6, 1810) was a cavalry officer of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, who held a final rank of brigadier general in the newly created United States after the war. Primarily ...

, and driven back in disarray. During the battle, With the main British infantry surrender and during Tarleton's retreat, Washington was in close pursuit and found himself somewhat isolated. He was attacked by the British commander and two of his men. Tarleton was stopped by Washington himself, who attacked him with his sword, calling out, "Where is now the boasting Tarleton?" A cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a so ...

of the 17th, Thomas Patterson, rode up to strike Washington but was shot by Washington's orderly trumpeter. Washington survived this assault and in the process wounded Tarleton's right hand with a sabre blow, while Tarleton creased Washington's knee with a pistol shot that also wounded his horse. Washington pursued Tarleton for sixteen miles, but gave up the chase when he came to the plantation of Adam Goudylock near Thicketty Creek. To escape capture by Washington, Tarleton had forced Goudylock to serve as an escape guide. The American War of Independence officially ended in 1783. An officer of the regiment, Captain Stapleton, had the distinction of delivering to George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

the despatch confirming the declaration of the cessation of hostilities.

French Revolutionary Wars

The regiment returned toIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, ├ēire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, where it remained until 1795, when it sailed for the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

to reinforce depleted forces battling the French. Two troops were used to suppress an uprising by "Maroons" in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

soon after arriving in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

. Other detachments were embarked aboard HMS ''Success'' as " supernumeraries". Their experience at sea has been suggested by regimental historians to have gained the regiment the nickname "Horse Marines". The regiment returned to England in August 1797. It was based in Ireland again from May 1803 to winter 1805.

Napoleonic Wars

In 1806, the regiment took part in the disastrous expeditions to Spanish-controlledSouth America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, then an ally of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803ŌĆō1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

.Cannon, p. 48 Sir Home Riggs Popham

Rear Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham, KCB, KCH (12 October 1762 ŌĆō 20 September 1820), was a Royal Navy commander who saw service against the French during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He is remembered for his scientific accomplishme ...

had orchestrated an expedition against South America without the British government's sanction. This invasion failed, but a second invasion was launched. The regiment was part of this second force, under Sir Samuel Auchmuty. The British force besieged and captured Montevideo

Montevideo () is the capital and largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . Montevideo is situated on the southern co ...

. In 1807, the regiment was part of the force, now under John Whitelocke

John Whitelocke (1757 ŌĆō 23 October 1833) was a British Army officer.

Military career

Educated at Marlborough Grammar School and at Lewis Loch├®e's military academy in Chelsea, Whitelocke entered the army in 1778 and served in Jamaica and in Sa ...

, that tried to capture Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Aut├│noma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the R├Ło de la Plata, on South ...

, but this failed abysmally. The British force (including the regiment), was forced to surrender, and did not return home until January 1808.

The regiment was sent to India shortly after returning home. It took part in the attack on the Pindarees in 1817 during the Third Anglo-Maratha War

The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817ŌĆō1819) was the final and decisive conflict between the English East India Company and the Maratha Empire in India. The war left the Company in control of most of India. It began with an invasion of Maratha ter ...

. Disease ravaged the regiment during its residency. While in India, the British Army nominally re-classified the regiment as lancer

A lancer was a type of cavalryman who fought with a lance. Lances were used for mounted warfare in Assyria as early as and subsequently by Persia, India, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. The weapon was widely used throughout Eurasia during the ...

s,Fortescue, p. 121 and added "lancers" as a subtitle to its regimental designation in 1822. The regiment did not learn of its new status until 1823, when, during a stopover at Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constit ...

on its journey back to Britain, a copy of the Army List

The ''Army List'' is a list (or more accurately seven series of lists) of serving regular, militia or territorial British Army officers, kept in one form or another, since 1702.

Manuscript lists of army officers were kept from 1702 to 1752, the ...

was obtained. Although the weapon's use had endured in parts of continental Europe, the lance had not been in British service for more than a century. Its reintroduction by the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, owed much to the performance of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 ŌĆō 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's Polish Uhlans. The lancer regiments adopted their own version of the Uhlan uniform, including the czapka

Czapka (, ; also spelt ''chapka'' or ''schapska'' ) is a Polish, Belarusian, and Russian generic word for a cap. However, it is perhaps best known to English speakers as a word for the 19th-century Polish cavalry headgear, consisting of a high ...

-style headdress.

In 1826, Lord Bingham (later the 3rd Earl of Lucan) became the regiment's commanding officer when he bought its lieutenant-colonelcy for the reputed sum of ┬Ż25,000 pounds. During his tenure, Bingham invested heavily in the regiment, purchasing uniforms and horses, giving rise to the regimental nickname "Bingham's Dandies".

Crimean War

The regiment landed at Calamita Bay near Eupatoria in September 1854 for service in theCrimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

and saw action, as part of the light brigade under the command of Major General the Earl of Cardigan, at the Battle of Alma

The Battle of the Alma (short for Battle of the Alma River) was a battle in the Crimean War between an allied expeditionary force (made up of French, British, and Ottoman forces) and Russian forces defending the Crimean Peninsula on 20Septem ...

in September 1854. The regiment, commanded by Captain William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 ŌĆō 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

, was in the first line of cavalry on the left flank during the Charge of the Light Brigade

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a failed military action involving the British light cavalry led by Lord Cardigan against Russian forces during the Battle of Balaclava on 25 October 1854 in the Crimean War. Lord Raglan had intended to ...

at the Battle of Balaclava

The Battle of Balaclava, fought on 25 October 1854 during the Crimean War, was part of the Siege of Sevastopol (1854ŌĆō55), an Allied attempt to capture the port and fortress of Sevastopol, Russia's principal naval base on the Black Sea. The en ...

in October 1854. The brigade drove through the Russian artillery before smashing straight into the Russian cavalry and pushing them back; it was unable to consolidate its position, however, having insufficient forces and had to withdraw to its starting position, coming under further attack as it did so. The regiment lost 7 officers and 67 men in the debacle. The regiment went on to take part in the Siege of Sevastopol in winter 1854. After the inception of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

in 1856, three members of the regiment received the award for acts of gallantry in the charge: These were Troop Sergeant-Major John Berryman

John Allyn McAlpin Berryman (born John Allyn Smith, Jr.; October 25, 1914 ŌĆō January 7, 1972) was an American poet and scholar. He was a major figure in American poetry in the second half of the 20th century and is considered a key figure in th ...

, Sergeant-Major Charles Wooden

Charles Wooden VC (24 March 1829 ŌĆō 24 April 1876) was a German-born soldier in the British Army and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth fo ...

, and Sergeant John Farrell.

Victorian era

In December 1857 the regiment arrived in India to reinforce the effort to suppress the

In December 1857 the regiment arrived in India to reinforce the effort to suppress the Indian rebellion

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857ŌĆō58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

against British rule. By the time the regiment was prepared for service, the rebellion was effectively over, although it did take part in the pursuit of Tatya Tope

Tantia Tope (also spelled Tatya Tope, : ╠¬a╦Ét╠¬╩▓a ╩ło╦Épe 6 January 1814 ŌĆō 18 April 1859) was a general in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and one of its notable leaders. Despite lacking formal military training, Tantia Tope is widely cons ...

, the rebel leader. During the course of the pursuit, Lieutenant Evelyn Wood earned the Victoria Cross for gallantry. The regiment returned to England in 1865. The regiment became the 17th Regiment of Lancers in August 1861. When, in 1876, it gained Prince George, Duke of Cambridge

Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (George William Frederick Charles; 26 March 1819 ŌĆō 17 March 1904) was a member of the British royal family, a grandson of King George III and cousin of Queen Victoria. The Duke was an army officer by professio ...

as its colonel-in-chief, the regiment adopted the title of the 17th (The Duke of Cambridge's Own) Lancers.

The regiment was sent to

The regiment was sent to Natal Colony

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three other colonies to ...

for service in the Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

and fought at the Battle of Ulundi

The Battle of Ulundi took place at the Zulu Kingdom, Zulu capital of Ulundi (Zulu:''oNdini'') on 4 July 1879 and was the last major battle of the Anglo-Zulu War. The British army broke the military power of the Zulu Kingdom, Zulu nation by def ...

under Sir Drury Curzon Drury-Lowe in July 1879. The regiment was deployed inside a large British infantry square

An infantry square, also known as a hollow square, was a historic combat formation in which an infantry unit formed in close order, usually when it was threatened with cavalry attack. As a traditional infantry unit generally formed a line to adva ...

during the attack by the Zulu Army, which had surrounded the British. When the attack appeared to be wavering, the regiment was ordered to advance: their charge routed the warriors with heavy loss and proved to be decisive. The regiment returned to India the same year, remaining there until about 1890 when they returned to England.

Second Boer War

In February 1900 a contingent from the regiment, comprising Lieutenant-Colonel E. F. Herbert and 500 troops, was deployed to

In February 1900 a contingent from the regiment, comprising Lieutenant-Colonel E. F. Herbert and 500 troops, was deployed to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

for service in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the AngloŌĆōBoer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

, and arrived to Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

on the SS ''Victorian'' early the next month. The contingent missed the large pitched battles, but still saw action during the war. In 1900, Sergeant Brian Lawrence won the regiment's fifth and final Victoria Cross at Essenbosch Farm. The contingent's most significant action was at the Battle of Elands River (Modderfontein) in September 1901. C Squadron was attacked by a unit of Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

s under the command of Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

; the Lancers mistakenly assumed the unit was friendly because of their attire. The Boers immediately opened fire, attacking from both the front and the rear. The Lancers suffered further casualties at a closed gate that slowed them down. Only Captain Sandeman, the squadron commander, and Lieutenant Lord Vivian survived. The regiment suffered 29 killed and 41 wounded before surrendering, while Boer losses were just one killed and six wounded.

They stayed in South Africa throughout the war, which ended June 1902 with the Peace of Vereeniging. Four months later, 540 officers and men left Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

on the SS ''German'' in late September 1902, and arrived at Southampton in late October, when they were posted to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, D├╣n ├łideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

.

First World War

The regiment, which was based in

The regiment, which was based in Sialkot

Sialkot ( ur, ) is a city located in Punjab, Pakistan. It is the capital of Sialkot District and the 13th most populous city in Pakistan. The boundaries of Sialkot are joined with Jammu (the winter capital of Indian administered Jammu and Ka ...

in India at the start of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, landed in France as part of the 2nd (Sialkot) Cavalry Brigade

The Sialkot Cavalry Brigade was a cavalry brigade of the British Indian Army formed in 1904 as a result of the Kitchener Reforms. It was mobilized as 2nd (Sialkot) Cavalry Brigade at the outbreak of the First World War as part of the 1st Indian ...

in the 1st Indian Cavalry Division in November 1914 for service on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

. The regiment fought in its conventional cavalry role at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917. The regiment was transferred to the 7th Cavalry Brigade, part of the 3rd Cavalry Division in February 1918 and was used as mobile infantry, plugging gaps whenever the need arose, both as cavalry and as infantry during the last-gasp German spring offensive.

After the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918, the regiment remained in continental Europe, joining the British Army of the Rhine

There have been two formations named British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). Both were originally occupation forces in Germany, one after the First World War and the other after the Second World War. Both formations had areas of responsibility located ...

in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: K├Čln ; ksh, K├Člle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

, Germany. The regiment then served in County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorca├Ł) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns a ...

, Ireland, where it operated against the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

during the War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of ...

. On 28 September 1920 IRA Volunteers led by Liam Lynch and Ernie O'Malley, raided the British Army barracks in Mallow, County Cork. They seized weaponry, freed prisoners and killed British serjeant W.G. Gibbs of the 17th Lancers. It was the only British Army barracks to be captured during the war. In 1921, the title of the regiment was altered to the 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own).

Amalgamation

The regiment was amalgamated with the 21st Lancers to form the 17th/21st Lancers in 1922.Regimental museum

The regimental collection is held atThe Royal Lancers and Nottinghamshire Yeomanry Museum

The Royal Lancers & Nottinghamshire Yeomanry Museum traces the history of three old and famous cavalry regiments, the Queen's Royal Lancers, the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry and the South Nottinghamshire Hussars. It is located at Thoresby Hall in ...

which is based at Thoresby Hall in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The trad ...

.

Battle honours

The regiment's battle honours were as follows: * ''Early wars'': Alma,Balaklava

Balaklava ( uk, ąæą░ą╗ą░ą║ą╗├Īą▓ą░, russian: ąæą░ą╗ą░ą║ą╗├Īą▓ą░, crh, Bal─▒qlava, ) is a settlement on the Crimean Peninsula and part of the city of Sevastopol. It is an administrative center of Balaklava Raion that used to be part of the Cri ...

, Inkerman

Inkerman ( uk, ąåąĮą║ąĄčĆą╝ą░ąĮ, russian: ąśąĮą║ąĄčĆą╝ą░ąĮ, crh, ─░nkerman) is a city in the Crimean peninsula. It is '' de facto'' within the federal city of Sevastopol within the Russian Federation, but '' de jure'' within Ukraine. It li ...

, Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, ąĪąĄą▓ą░čüč鹊╠üą┐ąŠą╗čī, Sevast├│pol╩╣, ; gkm, ╬Ż╬Ą╬▓╬▒ŽāŽä╬┐ŽŹŽĆ╬┐╬╗╬╣Žé, Sevasto├║polis, ; crh, ąÉą║čŖčÅ╠üčĆ, Aqy├Īr, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, Central India

Central India is a loosely defined geographical region of India. There is no clear official definition and various ones may be used. One common definition consists of the states of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, which are included in al ...

, South Africa 1879, South Africa 1900ŌĆō1902

* ''First World War'': Festubert, Somme 1916 __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

* Somme, Queensland, Australia

* Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river)

The Somme ( , , ) is a river in Picardy, northern France.

The ...

1918

This year is noted for the end of the First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50ŌĆō100 million people worldwide.

Events

Below, the events ...

, Morval, Cambrai 1917 1918

This year is noted for the end of the First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50ŌĆō100 million people worldwide.

Events

Below, the events ...

, St. Quentin

Saint Quentin ( la, Quintinus; died 287 AD) also known as Quentin of Amiens, was an early Christian saint.

Hagiography

Martyrdom

The legend of his life has him as a Roman citizen who was martyred in Gaul. He is said to have been the son of ...

, Avre, Lys, Hazebrouck, Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

, Hindenburg Line, St. Quentin Canal, Beaurevoir, Pursuit to Mons

Pursuit may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Films

* ''Pursuit'' (1935 film), a 1935 American action film

* ''Pursuit'' (1972 American film), a made-for-TV film directed by Michael Crichton

* ''Pursuit'' (1972 Hong Kong film), a Shaw Brot ...

, France and Flanders 1914ŌĆō18

The Western Front was one of the main theatres of war during the First World War. Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of imp ...

Regimental Colonels

Colonels of the regiment were: ;18th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons, or Hale's Light Horse *1763ŌĆō1770: Gen. John Hale ;17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (1769) *1770ŌĆō1782: Lt-Gen. George Preston *1782ŌĆō1785: Gen. Hon.Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of t ...

*1785ŌĆō1795: Maj-Gen. Thomas Pelham-Clinton, 3rd Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne

Major-General Thomas Pelham-Clinton, 3rd Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (1 July 1752 ŌĆō 18 May 1795), known as Lord Thomas Pelham-Clinton until 1779 and as Earl of Lincoln from 1779 to 1794, was a British Army officer and politician who sat in the ...

*1795ŌĆō1822: Gen. Oliver de Lancey

*1822ŌĆō1829: Gen. Lord Robert Edward Henry Somerset, GCB

;17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Lancers) (1823)

*1829ŌĆō1839: Lt-Gen. Sir John Elley, KCB, KCH

*1839: Lt-Gen. Sir Joseph Straton, CB, KCH

*1839ŌĆō1842: Gen. Sir Arthur Benjamin Clifton, GCB, KCH

*1842ŌĆō1852: F.M. HRH George William Frederick Charles, 2nd Duke of Cambridge, KG, KT, KP, GCB, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, GCVO, GBE, VD, TD

*1852ŌĆō1854: Maj-Gen. Thomas William Taylor

*1854ŌĆō1867: Gen. Sir James Maxwell Wallace, KH

;17th Regiment of Lancers (1861)

*1867ŌĆō1875: Lt-Gen. Charles William Morley Balders, CB

*1875ŌĆō1884: Gen. John Charles Hope Gibsone

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

;17th (The Duke of Cambridge's Own) Lancers (1876)

*1884ŌĆō1892: Gen. Henry Roxby Benson

Henry Roxby Benson (2 November 1818 ŌĆō 23 January 1892) was a 19th-century British General.

Life

Benson was born Camberwell into a distinguished Welsh family, the second son of merchant Thomas Starling Benson and his second wife, Elizabeth M ...

, CB

*1892ŌĆō1908: Lt-Gen. Sir Drury Curzon Drury-Lowe, GCB

*1908ŌĆō1912: Maj-Gen. Thomas Arthur Cooke, CVO

*1912ŌĆō1922: F.M. Sir Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 ŌĆō 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 unt ...

, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE (to 17th/21st Lancers)

In 1922, the regiment, as the 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own), was amalgamated with the 21st Lancers (Empress of India's)

The 21st Lancers (Empress of India's) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1858 and amalgamated with the 17th Lancers in 1922 to form the 17th/21st Lancers. Perhaps its most famous engagement was the Battle of Omdurman, where Wins ...

to form the 17th/21st Lancers.

Notable members

* Samuel BirchCannon, p. 66 *Frederick John Cokayne Frith

Lieutenant Frederick John Cokayne Frith (22 September 1858 ŌĆō 5 June 1879) was a Scottish officer in the British Army. He served as adjutant to Colonel Drury Drury-Lowe of the 17th Lancers cavalry regiment during the Anglo-Zulu War. He was kill ...

See also

* British cavalry during the First World WarReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

*The home of the recreated 17th Lancers ŌĆThe 17th Lancers

{{British Cavalry Regiments World War I 17 Lancers Military units and formations established in 1759 Military units and formations disestablished in 1922 L17 Regiments of the British Army in the Crimean War Regiments of the British Army in the American Revolutionary War 1759 establishments in Great Britain