Śāntarakṣita on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(

Śāntarakṣita (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

/ref> whose name translates into English as "protected by the One who is at peace" was an important and influential Indian

There are few historical records of Śāntarakṣita, with most available material being from hagiographic sources. Some of his history is detailed in a 19th-century commentary by Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso drawn from sources like the '' Blue Annals'', Buton and Taranatha. According to Ju Mipham, Śāntarakṣita was the son of the king of Zahor (in east India around the modern day states of

There are few historical records of Śāntarakṣita, with most available material being from hagiographic sources. Some of his history is detailed in a 19th-century commentary by Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso drawn from sources like the '' Blue Annals'', Buton and Taranatha. According to Ju Mipham, Śāntarakṣita was the son of the king of Zahor (in east India around the modern day states of

/ref> He then ordained the first seven Tibetan Buddhist monastics there with the aid of twelve Indian monks (circa 779). He stayed at Samye as the abbot (''upadhyaya'') for the rest of his life (thirteen years after completion). At Samye, Śāntarakṣita established a Buddhist monastic curriculum based on the Indian model. He also oversaw the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Tibetan. During this period, various other Indian scholars came to Tibet to work on translation, including Vimalamitra, Buddhaguhya, Santigrabha and Visuddhasimha. Tibetan sources state that he died suddenly in an accident after being kicked by a horse.

According to Tibetan sources, Śāntarakṣita and his students initially focused on teaching the 'ten good actions' (Sanskrit: ''daśakuśalakarmapatha''), the six paramitas (transcendent virtues), a summary of the

According to Tibetan sources, Śāntarakṣita and his students initially focused on teaching the 'ten good actions' (Sanskrit: ''daśakuśalakarmapatha''), the six paramitas (transcendent virtues), a summary of the

* Blumenthal, James. ''The Ornament of the Middle Way: A Study of the Madhyamaka Thought of Shantarakshita''. Snow Lion, (2004). – a study and translation of the primary Gelukpa commentary on Shantarakshita's treatise: Gyal-tsab Je's ''Remembering The Ornament of the Middle Way''. * Blumenthal, James and James Apple, "Śāntarakṣita", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

* Doctor, Thomas H. (trans.) Mipham, Jamgon Ju. ''Speech of Delight: Mipham's Commentary of Shantarakshita's Ornament of the Middle Way''. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications (2004). * Eltschinger, Vincent. "Śāntarakṣita" in ''Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume II: Lives (2019)'' * Ichigō, Masamichi (ed. & tr.). ''Madhyamakālaṁkāra of śāntarakṣita with his own commentary of Vṛtti and with the subcommentary or Pañjikā of Kamalaśīla''. Kyoto: Buneido (1985). * Jha, Ganganath (trans.) ''The Tattvasangraha of Shantaraksita with the Commentary of Kamalashila''. 2 volumes. First Edition : Baroda, (G.O.S. No. Lxxxiii) (1939). Reprint ; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, (1986). * Murthy, K. Krishna. ''Buddhism in Tibet''. Sundeep Prakashan (1989) . * Prasad, Hari Shankar (ed.). ''Santaraksita, His Life and Work.'' (Collected Articles from "''All India Seminar on Acarya Santaraksita''" held on 3–5 August 2001 at Namdroling Monastery, Mysore, Karnataka). New Delhi, Tibet House, (2003). * Phuntsho, Karma. ''Mipham's Dialectics and Debates on Emptiness: To Be, Not to Be or Neither''. London: RoutledgeCurzon (2005) * Śāntarakṣita (author); Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso (commentator);

online version

The Tattvasangraha (with commentary)

English translation by Ganganatha Jha, 1937 (includes glossary) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Santaraksita Indian Buddhist monks Indian scholars of Buddhism Madhyamaka Yogacara History of Tibetan Buddhism Buddhist logic Idealists Indian logicians Place of birth unknown Place of death unknown 725 births 8th-century Indian philosophers Monks of Nalanda

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

; , 725–788),stanford.eduŚāntarakṣita (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

/ref> whose name translates into English as "protected by the One who is at peace" was an important and influential Indian

Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

philosopher, particularly for the Tibetan Buddhist tradition . Śāntarakṣita was a philosopher of the Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhis ...

school who studied at Nalanda monastery under Jñānagarbha

Jñānagarbha (Sanskrit: ज्ञानगर्भ, Tibetan: ཡེ་ཤེས་སྙིང་པོ་, Wyl. ye shes snying po) was an 8th-century Buddhist philosopher from Nalanda who wrote on Madhyamaka and Yogacara and is considered part o ...

, and became the founder of Samye, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet.

Śāntarakṣita defended a synthetic philosophy which combined Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhis ...

, Yogācāra and the logico-epistemology of Dharmakirti into a novel Madhyamaka philosophical system .Blumenthal (2018) This philosophical approach is known as ''Yogācāra-Mādhyamika'' or ''Yogācāra-Svatantrika-Mādhyamika'' in Tibetan Buddhism. Unlike other Madhyamaka philosophers, Śāntarakṣita accepted Yogācāra doctrines like mind-only (''cittamatra'') and self-reflective awareness (''svasamvedana''), but only on the level of conventional truth.Blumenthal (2004), pp. 22-24. According to James Blumenthal, this synthesis is the final major development in Indian Buddhist philosophy before the disappearance of Buddhism from India (c. 12-13th centuries).

Biography

There are few historical records of Śāntarakṣita, with most available material being from hagiographic sources. Some of his history is detailed in a 19th-century commentary by Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso drawn from sources like the '' Blue Annals'', Buton and Taranatha. According to Ju Mipham, Śāntarakṣita was the son of the king of Zahor (in east India around the modern day states of

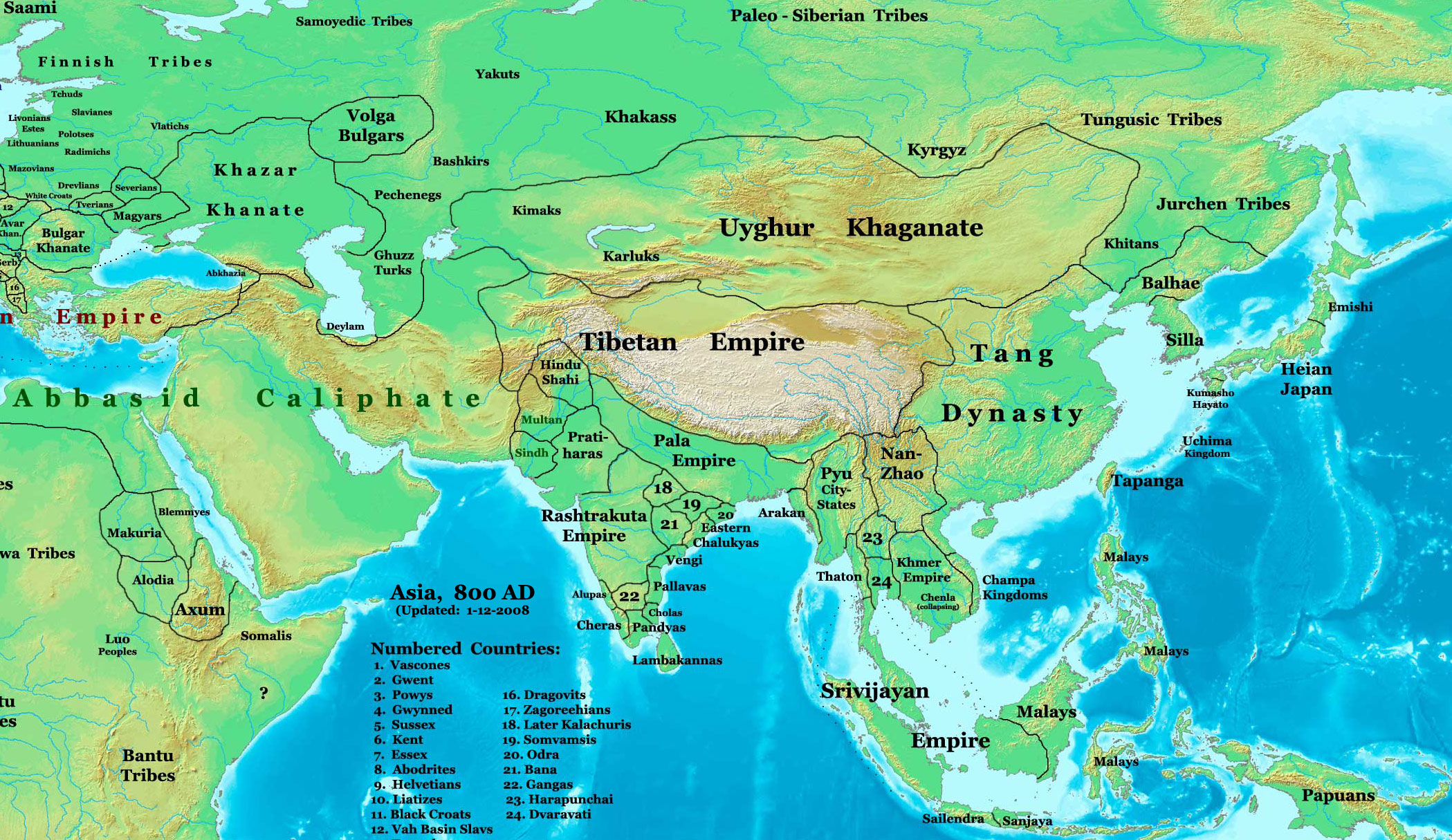

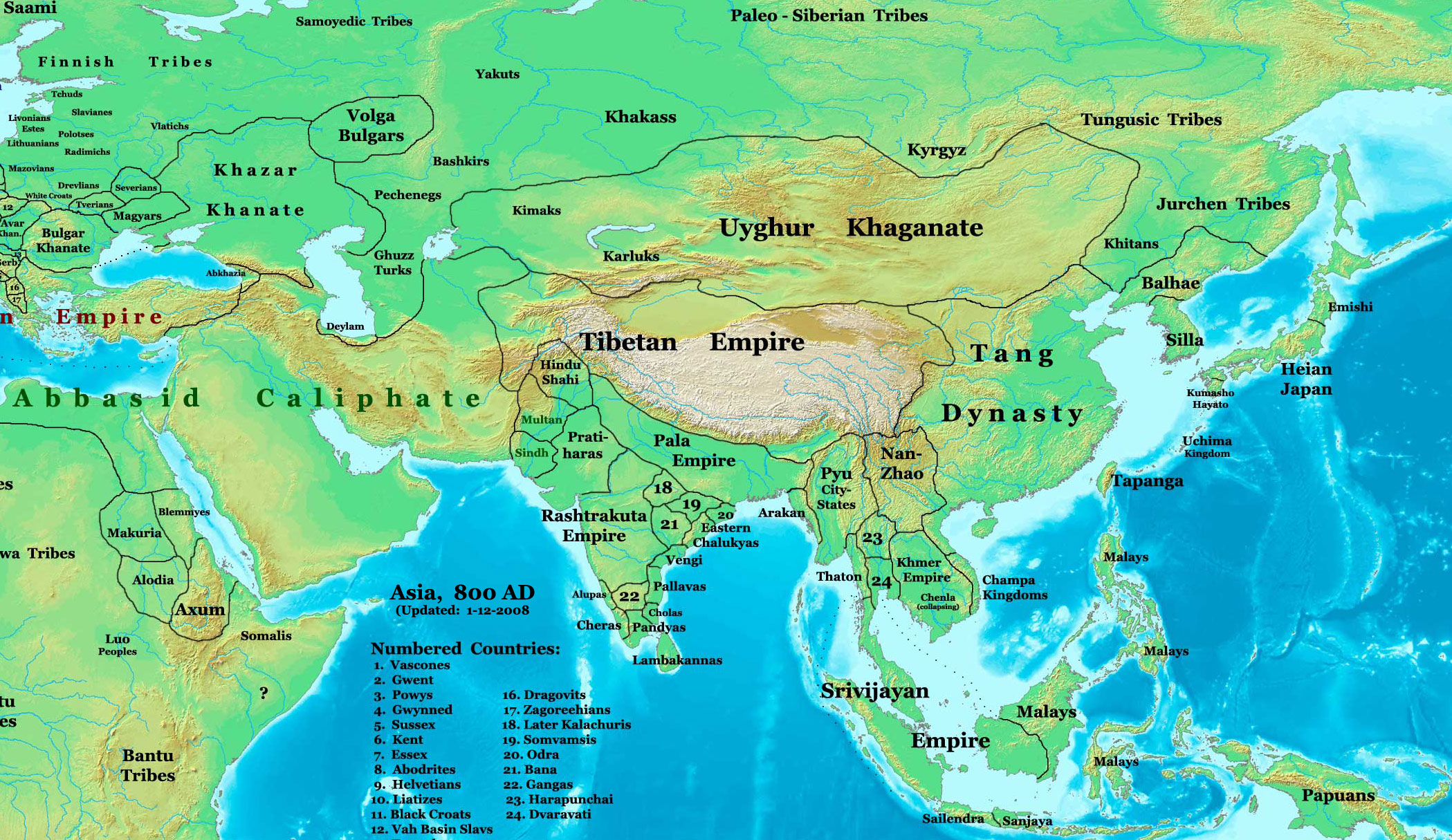

There are few historical records of Śāntarakṣita, with most available material being from hagiographic sources. Some of his history is detailed in a 19th-century commentary by Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso drawn from sources like the '' Blue Annals'', Buton and Taranatha. According to Ju Mipham, Śāntarakṣita was the son of the king of Zahor (in east India around the modern day states of Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

and Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

). Tibetan sources refer to him, Jñānagarbha and Kamalasila as ''rang rgyud shar gsum'' meaning the “three eastern Svātantrikas”.Shantarakshita & Ju Mipham (2005) pp.2–3

Most sources contain little information about his life in India, as such all that can be known is that he was an Indian monk in the Mulasarvastivada lineage in the Pala Empire. Tibetan sources also state he studied under Jñānagarbha

Jñānagarbha (Sanskrit: ज्ञानगर्भ, Tibetan: ཡེ་ཤེས་སྙིང་པོ་, Wyl. ye shes snying po) was an 8th-century Buddhist philosopher from Nalanda who wrote on Madhyamaka and Yogacara and is considered part o ...

, and eventually became the head of Nalanda University after mastering all branches of learning.

He was first invited to Tibet by king Trisong Detsen (c. 742–797) to help establish Buddhism there and his first trip to Tibet can be dated to 763. However, according to Tibetan sources like the '' Blue Annals,'' his first trip was unsuccessful and due to the activities of certain local spirits, he was forced to leave. He then spent six years in Nepal before returning to Tibet.

Tibetan sources then state that Śāntarakṣita later returned along with a tantric adept called Padmasambhava who performed the necessary magical rites to appease the unhappy spirits and to allow for the establishment of the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. Once this was done, Śāntarakṣita oversaw the construction of Samye monastery (meaning: "the Inconceivable", Skt. ''acintya'' ) starting in 775 CE on the model of the Indian monastery of Uddaṇḍapura.Banerjee, AC (1982) "Acarya Santaraksita"/ref> He then ordained the first seven Tibetan Buddhist monastics there with the aid of twelve Indian monks (circa 779). He stayed at Samye as the abbot (''upadhyaya'') for the rest of his life (thirteen years after completion). At Samye, Śāntarakṣita established a Buddhist monastic curriculum based on the Indian model. He also oversaw the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Tibetan. During this period, various other Indian scholars came to Tibet to work on translation, including Vimalamitra, Buddhaguhya, Santigrabha and Visuddhasimha. Tibetan sources state that he died suddenly in an accident after being kicked by a horse.

Philosophy and teachings

According to Tibetan sources, Śāntarakṣita and his students initially focused on teaching the 'ten good actions' (Sanskrit: ''daśakuśalakarmapatha''), the six paramitas (transcendent virtues), a summary of the

According to Tibetan sources, Śāntarakṣita and his students initially focused on teaching the 'ten good actions' (Sanskrit: ''daśakuśalakarmapatha''), the six paramitas (transcendent virtues), a summary of the Mahāyāna

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

and 'the chain of dependent origination' ('' pratītyasamutpāda'').Dargyay, Eva M. (author) & Wayman, Alex (editor) (1977, 1998). ''The Rise of Esoteric Buddhism in Tibet''. Second revised edition, reprint. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt Ltd. Buddhist Tradition Series Vol. 32. (paper), p.7

Tibetan sources indicate that he and his student Kamalaśīla mainly taught a gradual path to Buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (; Pali, Sanskrit: 𑀩𑀼𑀤𑁆𑀥, बुद्ध), "awakened one", is a title for those who are awake, and have attained nirvana and Buddhahood through their own efforts and insight, without a teacher to point o ...

(most thoroughly outlined in the ''Bhāvanākrama

The Bhāvanākrama (Bhk, "cultivation process" or "stages of meditation"; Tib. , ) is a set of three Buddhist texts written in Sanskrit by the Indian Buddhist scholar yogi Kamalashila (c. 9th century CE) of Nalanda university.Adam, Martin T. Med ...

'' of Kamalaśīla). Ju Mipham writes that when he came to Tibet, "he set forth the ten good virtues, the eighteen dhatus, and the twelve fold chain of dependent arising."

Śāntarakṣita is best known for his syncretic interpretation of Madhyamaka philosophy which also makes use of Yogācāra and Dharmakirtian epistemology. His Madhyamaka view is most clearly outlined in his ''Madhyamakālaṃkāra'' (''The Ornament of the Middle Way'') and his own commentary on that text, the ''Madhyamakālaṃkāravṛtti'' (''The Auto-Commentary on The Ornament of the Middle Way'') . Śāntarakṣita is not the first Buddhist thinker to attempt a synthesis of Madhyamaka thought with Yogācāra. Though Śāntarakṣita is often regarded as the leading exponent of this approach, earlier figures such as Vimuktisena, Srigupta and Śāntarakṣita's teacher Jñānagarbha had already written from a similar syncretic perspective.

Like other Indian Madhyamaka thinkers, Śāntarakṣita explains the ontological status of phenomena through the use of the doctrine of the "two truths": the ultimate (''paramārtha'') and the conventional ('' saṃvṛti''). While in an ultimate or absolute sense, all phenomena as seen by Madhyamaka as being "empty" (''shunya'') of essence or inherent nature (''svabhāva

Svabhava ( sa, स्वभाव, svabhāva; pi, सभाव, sabhāva; ; ) literally means "own-being" or "own-becoming". It is the intrinsic nature, essential nature or essence of beings.

The concept and term ''svabhāva'' are frequently enco ...

''), they can be said to have some kind of conventional, nominal or provisional existence . James Blumenthal summarizes Śāntarakṣita's syncretic view thus: "Śāntarakṣita advocates a Madhyamaka perspective when describing ultimate truths, and a Yogācāra perspective when describing conventional truths."

According to Blumenthal, Śāntarakṣita's thought also emphasized the importance of studying the "lower" Buddhist schools. These lesser views were "seen as integral stepping stones on the ascent to his presentation of what he considered to be the ultimately correct view of Madhyamaka." This way of using a doxographic hierarchy to present Buddhist philosophy remains influential in Tibetan Buddhist thought.

Ultimate Truth and neither-one-nor-many

Like other Madhyamaka thinkers, Śāntarakṣita sees the ultimate truth as being the emptiness of all phenomena (i.e., their lack of inherent existence or essence). He makes use of the "neither-one-nor-many argument" in his ''Madhyamakālaṃkāra'' as a way to argue for emptiness. The basic position is outlined by the following stanza:These entities, as asserted by our own uddhist schoolsand other on-Buddhist schools have no inherent nature at all because in reality they have neither a singular nor manifold nature, like a reflected image.The main idea in his argument is that any given phenomenon (i.e. ''dharma''), cannot be said to have an inherent nature or essence (i.e. ''svabhāva''), because such a nature cannot be proven to exist either as a singular nature (''ekasvabhāva'') or as a multiplicity of natures (''anekasvabhāva''). In the ''Madhyamakālaṃkāra'', Śāntarakṣita analyses all the different phenomena posited by Buddhist and non-Buddhist schools through the neither-one-nor-many schema, proving that they cannot be shown to exist as a single thing or as a manifold collection of many phenomena. Śāntarakṣita usually begins by looking at any phenomenon that is asserted by his interlocutor as having a truly singular nature and then showing how it cannot actually be singular. For example, when analyzing the

Sāṃkhya

''Samkhya'' or ''Sankya'' (; Sanskrit सांख्य), IAST: ') is a dualistic school of Indian philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, '' puruṣa'' ('consciousness' or spirit); and ''prakṛti'', (nature ...

school's doctrine of a Fundamental Nature (''Prakṛti

Prakriti ( sa, प्रकृति ) is "the original or natural form or condition of anything, original or primary substance". It is a key concept in Hinduism, formulated by its Sāṅkhya school, where it does not refer to matter or nature, b ...

'', the permanent, un-caused absolute cause of everything), Śāntarakṣita states that this permanent and fundamental nature cannot be truly singular because it "contributes to the production of successive effects." Since "each successive effect is distinct", then this fundamental nature which is contributing to all these different effects arising at different times is not really singular.

After critiquing the non-Buddhist ideas, Śāntarakṣita turns his arguments against Buddhist ideas, such as the theory of ''svabhāva,'' the theory of atoms (''paramanu''), the theory of the person (''pudgala''), theories regarding space (''akasa'') and nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lamp Richard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colomb ...

. He also critiques the Sautrantika and Yogacara Buddhists who held that consciousness ('' vijñāna'') is truly singular and yet knows a variety of objects. In his analysis of consciousness, Śāntarakṣita concludes that it is just like other entities in the sense that it can be neither unitary nor multiple. Therefore, he (like other Madhyamikas) refuses to assign any ultimate reality to consciousness and sees it as empty of any inherent nature.Ruegg, David Seyfort (1981) ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India'', p. 92. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden Furthermore, he also critiques the Yogacara theory of the three natures.

Śāntarakṣita then turns to a critique of the idea that there is a truly manifold nature in phenomena. Śāntarakṣita's main argument here is that any manifold nature or essence would depend on an aggregation of singular essences. But since singular essences have been proven to be irrational, then there can also be no manifold essence. Because of this, phenomena cannot have any inherent nature or essence at all, since the very idea of such a thing is irrational.

The Conventional

All Madhyamikas agree on an anti-essentialist view which rejects all permanent essences, inherent natures, or true existence. However, they do not all agree on conventional truth, that is, the best way of describing how it is that phenomena "exist" in a relative sense. In his ''Madhyamakālaṃkāra'', Śāntarakṣita argues that phenomena which are "characterized only by conventionality" are those phenomena that "are generated and disintegrate and those that have the ability to function." According to Blumenthal, the main criteria for conventional entities given by Śāntarakṣita in his ''Madhyamakālaṃkāra'' and its commentary are the following: # that which is known by a mind, # that which has the ability to function (''i.e.'', that it is causally efficacious), # that which isimpermanent

Impermanence, also known as the philosophical problem of change, is a philosophical concept addressed in a variety of religions and philosophies. In Eastern philosophy it is notable for its role in the Buddhist three marks of existence. It ...

, and

# that which is unable to withstand analysis which searches for an ultimate nature or essence in entities.

Furthermore, causal efficacy and impermanence are qualities that conventional truths have due to the fact that they are dependently originated, that is, they arise due to causes and conditions which are themselves impermanent (and so on). Also, conventional truths are described by Śāntarakṣita as being known by conceptual thought and designated based on worldly custom.

One important element of Śāntarakṣita's presentation of conventional truth is that he also incorporates certain views from the Yogācāra school, mainly the idea that conventional phenomena are just consciousness as well as the concept of self-cognizing consciousness or reflexive awareness ('' svasamvedana''). The ''Madhyamakālaṃkāra'' argues in favor of the Yogācāra position on a conventional level and states that "that which is cause and result is mere consciousness only." Thus, Śāntarakṣita incorporates the Yogācāra school's analysis into his Madhyamaka framework as a useful way of understanding conventional reality and as a stepping stone to the highest view of emptiness of all phenomena.

Works

Around 11 works may have been written by Śāntarakṣita, some survive in Tibetan translation and others in Sanskrit. Some of his texts survive inJain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

libraries, showing that he was a figure that was taken seriously even by some of his non-Buddhist opponents.

His main known works include:Eltschinger (2019)

* ''*Aṣṭatathāgatastotra'' (D 1166/ P 2055), a short praise

* ''*Śrīva-jradharasaṅgītibhagavatstotraṭīkā'' (D 1163/ P 2052), a short praise

* ''Tattvasiddhi'' (D 39a1/ P 42a8), a philosophical defense of tantra, the authorship is doubtful.

* ''Saṅvaraviṃśakavṛtti'' (D 4082/ P 5583), focuses on the training and practice of a bodhisattva and is actually a commentary on Candragomin's ''Bodhisattvasaṃvaraviṃśaka.'' It is also related to the ''Bodhisattvabhumi.''

* ''Satyadvayavibhaṅgapañjikā'' (D 3883/ P 5283), an extensive commentary on Jñānagarbha's ''Satyadvayavibhaṅga.'' The authorship has been questioned by various scholars, including some Tibetans like Tsongkhapa and Taranatha.

* ''Paramārthaviniścaya'', now lost.

* ''Vādanyāyaṭīkā vipañcitārthā'' (D 4239/ P 5725), a commentary on Dharmakīrti's Vādanyāya

* ''Tattvasaṅgraha'', a massive polemical compendium of Indian philosophy covering Buddhist and non-Buddhist views. There is also a commentary on this text by Kamalaśīla.

* ''Madhyamakālaṅkāra'' and its autocommentary, the ''Madhyamakālaṅkāravṛtti''. This is his main exposition of his synthetic Madhyamaka views. Kamalaśīla also composed a commentary to this text, the ''Madhyamakālaṅkārapañjikā.''

''Tattvasaṅgraha''

Śāntarakṣita's ''Tattvasaṅgraha'' (''Compendium on Reality''/''Truth'') is a huge and encyclopaedic treatment (over 3,600 verses distributed into 26 chapters) of the major Indian philosophic views of the time. In this text, the author outlines the views of the numerous non-Buddhist Indian traditions of his time. Unlike previous Madhyamaka texts which were organized around Buddhist categories to be refuted and discussed, the ''Tattvasaṅgraha'' is mainly organized around refuting non-Buddhist views which were becoming increasingly sophisticated and prominent during Śāntarakṣita's era (though space is also saved for certain Buddhist views as well, like pudgalavada i.e. "personalism"). In this text, Śāntarakṣita explains and then refutes many non-Buddhist views systematically, including Sāṅkhya's primordial matter Nyāya's creator god ( Īśvara) and six different theories on the self ( ātman). He also defends the Buddhist doctrine of momentariness, rejects theVaiśeṣika

Vaisheshika or Vaiśeṣika ( sa, वैशेषिक) is one of the six schools of Indian philosophy (Vedic systems) from ancient India. In its early stages, the Vaiśeṣika was an independent philosophy with its own metaphysics, epistemolog ...

ontological categories, discusses philosophy of language and epistemology as well as Jain theories, Sarvastivada

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosop ...

philosophy, and critiques the materialism of the Cārvākas and the scriptural views of Mīmāṃsā.

A Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

version of this work was discovered in 1873 by Dr. G. Bühler in the Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

temple of Pārśva

''Parshvanatha'' (), also known as ''Parshva'' () and ''Parasnath'', was the 23rd of 24 ''Tirthankaras'' (supreme preacher of dharma) of Jainism. He is the only Tirthankara who gained the title of ''Kalīkālkalpataru (Kalpavriksha in this "K ...

at Jaisalmer

Jaisalmer , nicknamed "The Golden city", is a city in the Indian state of Rajasthan, located west of the state capital Jaipur. The town stands on a ridge of yellowish sandstone and is crowned by the ancient Jaisalmer Fort. This fort contains a ...

. This version contains also the commentary by Śāntarakṣita's pupil Kamalaśīla.

''Madhyamakālaṅkāra''

Śāntarakṣita's synthesis of Madhyamaka, Yogacara, and Dharmakirtian thought was expounded in his '' Madhyamakālaṅkāra'' (''Ornament of the Middle Way''). In this short verse text, Śāntarakṣita critiques some key Hindu and Buddhist views and then details his presentation of the two truths doctrine. This presents Yogacara Idealism as the superior way of analyzing conventional truth while retaining the Madhyamaka philosophy of emptiness as the ultimate truth. In the last verses of this text, he summarizes his approach as follows:“Based on the standpoint of mind-only one must know the non-existence of external entities. Based on this standpoint of the non-intrinsic nature of all dharmas one must know that there is no self at all even in that which is mind-only. Therefore, those who hold the reins of logic while riding the carriage of the two systems ādhyamika and Yogācāra attain the stage of a true Mahāyānist.”

Influence

Mipham lists Śāntarakṣita's main Indian students as Kamalaśīla, Haribhadra and Dharmamitra. He also notes that other Indian scholars like masters Jñanapada, and Abhayākaragupta (c. 1100 CE) "also established the view of Prajnaparamita in accordance with this tradition."Shantarakshita & Ju Mipham (2005) p. 86. Furthermore, according to David Seyfort Ruegg, other later Indian scholars such as Vidyākaraprabha (c. 800 CE), Nandasri, Buddhajñāna(pāda), Jitāri, and Kambalapāda also belongs to this Yogācāra-Mādhyamaka tradition.Ruegg, David Seyfort (1981) ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India'', pp. 99-107. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. Ju Mipham further states that this tradition was continued by Tibetan scholars such as Ngok Lotsawa, Chaba Chökyi Senge and Rongton Choje. Śāntarakṣita's work also influenced numerous later Tibetan figures such as Yeshe De (''ca.'' 8th c.), Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) and Ju Mipham Gyatso (1846–1912) . Śāntarakṣita's philosophy remained the main interpretation of Madhyamaka in Tibetan Buddhism from the 8th century until the time of the second dissemination in the eleventh and twelfth centuries when Candrakirti's work began to be translated. Blumenthal notes that already in the time of Patsab (12th century) "the Prasaṅgika-Madhyamaka view began to be widely taught and the privileging of Śāntarakṣita's system began to encounter serious opposition."Blumenthal (2004) p. 27. Je Tsongkhapa's (1357-1419) interpretation of Prasaṅgika Madhyamaka, and his new school, theGelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).">Bodh_Gaya.html" ;"title="Kalachakra ceremony, Bodh Gaya">Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuou ...

, raised serious and influential critiques of Śāntarakṣita's position. In no small part due to his efforts, Prasaṅgika Madhyamaka replaced Śāntarakṣita's Madhyamaka as the dominant interpreation of Madhyamaka in Tibetan Buddhism.

In the late 19th century, Ju Mipham attempted to promote Yogācāra-Mādhyamaka again as part of the Rimé movement and as a way to discuss specific critiques of Je Tsongkhapa's widely influential philosophy. The Rimé movement was funded by the secular authorities in Derge, Kham, and began to establish centres of learning encouraging the study of traditions different from the dominant Gelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).">Bodh_Gaya.html" ;"title="Kalachakra ceremony, Bodh Gaya">Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuou ...

tradition in central Tibet. This Rimé movement revitalised the Sakya, Kagyu, Nyingma

Nyingma (literally 'old school') is the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It is also often referred to as ''Ngangyur'' (, ), "order of the ancient translations". The Nyingma school is founded on the first lineages and trans ...

and Jonang traditions, which had been by almost supplanted by the Gelug hegemony.Shantarakshita & Ju Mipham (2005) pp.4–5

As part of that movement the 19th century Nyingma scholar Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso wrote the first commentary in almost 400 years about Śāntarakṣita's ''Madhyamakālaṅkāra''. According to his student Kunzang Palden, Mipham had been asked by his teacher Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo to write a survey of all the major Mahayana philosophic shastras for use in the Nyingma monastic colleges. Mipham's commentaries now form the backbone of the Nyingma monastic curriculum. The ''Madhyamakālaṅkāra'', which was almost forgotten by the 19th century, is now studied by all Nyingma shedra

Shedra is a Tibetan word () meaning "place of teaching" but specifically refers to the educational program in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and nunneries. It is usually attended by monks and nuns between their early teen years and early twenties. N ...

students.

References

Sources

* Banerjee, Anukul Chandra. ''Acaraya Santaraksita'' in Bulletin of Tibetology, New Series No. 3, p. 1–5. (1982). Gangtok, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology and Other Buddhist Studies* Blumenthal, James. ''The Ornament of the Middle Way: A Study of the Madhyamaka Thought of Shantarakshita''. Snow Lion, (2004). – a study and translation of the primary Gelukpa commentary on Shantarakshita's treatise: Gyal-tsab Je's ''Remembering The Ornament of the Middle Way''. * Blumenthal, James and James Apple, "Śāntarakṣita", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

* Doctor, Thomas H. (trans.) Mipham, Jamgon Ju. ''Speech of Delight: Mipham's Commentary of Shantarakshita's Ornament of the Middle Way''. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications (2004). * Eltschinger, Vincent. "Śāntarakṣita" in ''Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume II: Lives (2019)'' * Ichigō, Masamichi (ed. & tr.). ''Madhyamakālaṁkāra of śāntarakṣita with his own commentary of Vṛtti and with the subcommentary or Pañjikā of Kamalaśīla''. Kyoto: Buneido (1985). * Jha, Ganganath (trans.) ''The Tattvasangraha of Shantaraksita with the Commentary of Kamalashila''. 2 volumes. First Edition : Baroda, (G.O.S. No. Lxxxiii) (1939). Reprint ; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, (1986). * Murthy, K. Krishna. ''Buddhism in Tibet''. Sundeep Prakashan (1989) . * Prasad, Hari Shankar (ed.). ''Santaraksita, His Life and Work.'' (Collected Articles from "''All India Seminar on Acarya Santaraksita''" held on 3–5 August 2001 at Namdroling Monastery, Mysore, Karnataka). New Delhi, Tibet House, (2003). * Phuntsho, Karma. ''Mipham's Dialectics and Debates on Emptiness: To Be, Not to Be or Neither''. London: RoutledgeCurzon (2005) * Śāntarakṣita (author); Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso (commentator);

Padmakara Translation Group

Padmasambhava ("Born from a Lotus"), also known as Guru Rinpoche (Precious Guru) and the Lotus from Oḍḍiyāna, was a tantric Buddhist Vajra master from India who may have taught Vajrayana in Tibet (circa 8th – 9th centuries)... According ...

(translators)(2005). ''The Adornment of the Middle Way: Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with commentary by Jamgön Mipham.'' Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Shambhala Publications, Inc. (alk. paper)

* Sodargye, Khenpo ( 索达吉堪布) (trans.) . ''中观庄严论释'' (A Chinese translation of the Mipham's Commentary of Ornament of the Middle Way)online version

Further reading

* Śāntarakṣita (author); Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso (commentator);Padmakara Translation Group

Padmasambhava ("Born from a Lotus"), also known as Guru Rinpoche (Precious Guru) and the Lotus from Oḍḍiyāna, was a tantric Buddhist Vajra master from India who may have taught Vajrayana in Tibet (circa 8th – 9th centuries)... According ...

(translators)(2005). ''The Adornment of the Middle Way: Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with commentary by Jamgön Mipham.'' Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Shambhala Publications, Inc. (alk. paper)

External links

The Tattvasangraha (with commentary)

English translation by Ganganatha Jha, 1937 (includes glossary) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Santaraksita Indian Buddhist monks Indian scholars of Buddhism Madhyamaka Yogacara History of Tibetan Buddhism Buddhist logic Idealists Indian logicians Place of birth unknown Place of death unknown 725 births 8th-century Indian philosophers Monks of Nalanda