ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips

In the following year, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook a much more extensive journey to the United States and

In the following year, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook a much more extensive journey to the United States and

Rabindranath Tagore: Some Encounters with Baháʼís

'.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Washington DC from 8 to 11 May, when he then returned to the New York City area. On 12 May he visited Montclair, NJ, and then on 14 May he went to northern

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Washington DC from 8 to 11 May, when he then returned to the New York City area. On 12 May he visited Montclair, NJ, and then on 14 May he went to northern

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's arrived in Paris on 22 January; the visit which was his second to the city last for a couple months. During his stay in the city he continued his public talks, as well as with meeting Baháʼís, including locals, those from Germany, and those who had come from the East specifically to meet with him. During his stay in Paris, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's stayed at an apartment at 30 Rue St Didier which was rented for him by Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney.

Some of the notables that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met while in Paris include the Persian minister in Paris, several prominent Ottomans from the previous regime, professor 'Inayatu'llah Khan, and

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's arrived in Paris on 22 January; the visit which was his second to the city last for a couple months. During his stay in the city he continued his public talks, as well as with meeting Baháʼís, including locals, those from Germany, and those who had come from the East specifically to meet with him. During his stay in Paris, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's stayed at an apartment at 30 Rue St Didier which was rented for him by Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney.

Some of the notables that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met while in Paris include the Persian minister in Paris, several prominent Ottomans from the previous regime, professor 'Inayatu'llah Khan, and

(pp. 16–17)

* * * * * *

Commemorating ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in America - 1912-2012 Centenary

The Journey West: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Travels - Europe & North America (1911-1913)

* * BWNS:

100 years ago, historic journeys transformed a fledgling faith

' (30 August 2010). * * *

ʻIrfán Colloquium #97 (English)

Centre for Baháʼí Studies: Acuto, Italy on 3–6 July 2010 - the beginning of a four-year centenary celebration of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks, and significant events associated with his historic travels to the West (1911–1913) {{DEFAULTSORT:Abdu'l-Baha's Journeys to the West History of the Bahá'í Faith Bahá'í pilgrimages

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

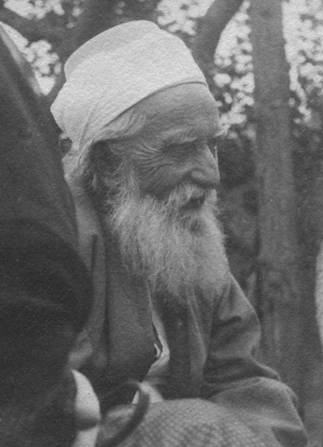

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (; Persian: , 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born ʻAbbás ( fa, عباس), was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh and served as head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 until 1921. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was later canonized as the ...

undertook starting at the age of 66, journeying continuously from Palestine to the West between 1910 and 1913. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh

Baháʼu'lláh (born Ḥusayn-ʻAlí; 12 November 1817 – 29 May 1892) was the founder of the Baháʼí Faith. He was born to an aristocratic family in Qajar Iran, Persia, and was exiled due to his adherence to the messianic Bábism, Bábí ...

, founder of the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Established by Baháʼu'lláh in the 19th century, it initially developed in Iran and parts of the ...

, and suffered imprisonment with his father starting at the age of 8; he suffered various degrees of privation for almost 55 years, until the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

in 1908 freed religious prisoners of the Ottoman Empire. Upon the death of his father in 1892, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had been appointed as the successor, authorized interpreter of Bahá'u'lláh's teachings, and Center of the Covenant of the Baháʼí Faith.

At the time of his release, the major centres of Baháʼí population and scholarly activity were mostly in Iran, with other large communities in Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world an ...

, Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

, Ashgabat

Ashgabat or Asgabat ( tk, Aşgabat, ; fa, عشقآباد, translit='Ešqābād, formerly named Poltoratsk ( rus, Полтора́цк, p=pəltɐˈratsk) between 1919 and 1927), is the capital and the largest city of Turkmenistan. It lies ...

, Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

, and Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

.

Meanwhile, in the Occident

The Occident is a term for the West, traditionally comprising anything that belongs to the Western world. It is the antonym of ''Orient'', the Eastern world. In English, it has largely fallen into disuse. The term ''occidental'' is often used to ...

the religion had been introduced in the late 1890s in several locales, with the very first mention of Baha'u'llah occuring in a talk given by a Christian missionary during the First World Parliament of Religions held in conjunction with the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. However, by 1910 the religion's followers still numbered less than a few thousands across the entire West. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá thus took steps to personally present the Baháʼí teachings

The Baháʼí teachings represent a considerable number of theological, ethical, social, and spiritual ideas that were established in the Baháʼí Faith by Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion, and clarified by its successive leaders: ʻA ...

to the West by traveling to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

. His first excursion outside of Palestine and Iran was to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

in 1910 where he stayed for around a year, followed by a near five-month trip to France and Great Britain in 1911. After returning to Egypt, he left on a trip to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

which lasted nearly eight months. During that trip he visited many cities across the United States, from major metropolitan areas on the eastern coast of the country, to cities in the midwest, and California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

on the west coast; he also visited Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Following his trip in North America he visited various countries in Europe, including France, Britain and Germany for six months, followed by a six-month stay again in Egypt, before returning to Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

.

With his visits to the West, the small Western Baháʼí community was given a chance to consolidate and embrace a wider vision of the religion; the religion also attracted the attention of sympathetic attention from both religious, academic, and social leaders as well as in newspapers which provided significant coverage of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visits. During his travels ʻAbdu'l-Bahá would give talks at the homes of Baháʼís, at hotels, and at other public and religious sites, such as the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, at the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&n ...

, at Howard

Howard is an English-language given name originating from Old French Huard (or Houard) from a Germanic source similar to Old High German ''*Hugihard'' "heart-brave", or ''*Hoh-ward'', literally "high defender; chief guardian". It is also probabl ...

and Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. S ...

universities, and at various Theosophical Societies, among others. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá talks across the West also became an important addition to the body of Baháʼí literature

Baháʼí literature covers a variety of topics and forms, including scripture and inspiration, interpretation, history and biography, introduction and study materials, and apologia. Sometimes considerable overlap between these forms can be ob ...

. In succeeding decades after his visit the American community substantially grew and then spread across South America, Australasia, Subsaharan Africa and the Far East.

During these journeys Bahíyyih Khánum, his sister, was given the position of acting head of the religion.

Trip to Egypt

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá leftHaifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

for Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

, Egypt on 29 August 1910. Earlier on that day he had accompanied two pilgrims to the Shrine of the Báb

The Shrine of the Báb is a structure on the slopes of Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel, where the remains of the Báb, founder of the Bábí Faith and forerunner of Baháʼu'lláh in the Baháʼí Faith, are buried; it is considered to be the seco ...

, and then he headed down to the port in the city where at around 4pm he set sail on the steamer "Kosseur London" and then telegrammed the Baháʼís in Haifa that he was in Egypt. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in the city for around one month where Baháʼís from Cairo came to visit him.

On 1 October, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá again set sail; his intention was to go to Europe, but because of his poor health, he instead landed in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

where he stayed for nearly eight months. While in Egypt there was increasingly positive coverage of him and the Baháʼís from various Egyptian news outlets. While in Alexandria he met with a larger number of people. In November he met with Briton Wellesley Tudor Pole

Wellesley Tudor Pole OBE (23 April 1884 – 13 September 1968) was a spiritualist and early British Baháʼí.

He authored many pamphlets and books and was a lifelong pursuer of religious and mystical questions and visions, being particularl ...

who later became a Baháʼí. He also was visited by Russian/Polish Isabella Grinevskaya who also became a Baháʼí. In late April Louis Gregory

Louis George Gregory (born June 6, 1874, in Charleston, South Carolina; died July 30, 1951, in Eliot, Maine) was a prominent American member of the Baháʼí Faith who was devoted to its expansion in the United States and elsewhere. He traveled ...

, an Africa-American who had gone on Baháʼí pilgrimage, met with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá while he was in the suburb of Ramleh. Later in May ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved to Cairo and got more favourable press coverage, including from Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' ( ar, الأهرام; ''The Pyramids''), founded on 5 August 1875, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second oldest after '' al-Waqa'i`al-Masriya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majori ...

. During his time there he met the Mufti of Egypt, with Abbas II of Egypt

Abbas II Helmy Bey (also known as ''ʿAbbās Ḥilmī Pāshā'', ar, عباس حلمي باشا) (14 July 1874 – 19 December 1944) was the last Khedive ( Ottoman viceroy) of Egypt and Sudan, ruling from 8January 1892 to 19 December 19 ...

, the Khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"K ...

of Egypt.

Finally on 11 August 1911 ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Egypt towards Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. He boarded the ''SS Corsican'', an Allan Line Royal Mail Steamer towards the port of Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, France accompanied by secretary Mírzá Mahmúd, and personal assistant Khusraw. Memoirs that cover the periods in Egypt include .

First trip to Europe

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first European trip spanned from August to December 1911, at which time he returned to Egypt. During his first European trip he visitedLake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

on the border of France and Switzerland, Great Britain and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, France. The purpose of these trips was to support the Baháʼí communities in the West and to further spread his father's teachings, after sending representatives and a letter to the First Universal Races Congress

The First Universal Races Congress met in 1911 for four days at the University of London as an early effort at anti-racism. Speakers from a number of countries discussed race relations and how to improve them. The congress, with 2,100 attendees, ...

in July.

Various memoirs cover this period.Note several volumes covering the talks given on ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys are of incomplete substantiation — "The Promulgation of Universal Peace", "Paris Talks" and "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London" contain transcripts of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks in North America, Paris and London respectively. While there exists original Persian transcripts of some, but not all, of the talks from "The Promulgation of Universal Peace", "Paris Talks", there are no original transcripts for the talks in "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London". See .

*

*

*

Lake Geneva

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Marseille, he was greeted by , a prominent early French Baháʼí. Dreyfus-Barney accompanied ʻAbdu'l-Bahá toThonon-les-Bains

Thonon-les-Bains (; frp, Tonon), often simply referred to as Thonon, is a subprefecture of the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in Eastern France. In 2018, the commune had a population of 35,241. Thonon-les-Bains is ...

, a French town, on Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

that straddles France and Switzerland.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Thonon-les-Bains

Thonon-les-Bains (; frp, Tonon), often simply referred to as Thonon, is a subprefecture of the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in Eastern France. In 2018, the commune had a population of 35,241. Thonon-les-Bains is ...

in France for a few days before going to Vevey in Switzerland. In Vevey

Vevey (; frp, Vevê; german: label=former German, Vivis) is a town in Switzerland in the canton of Vaud, on the north shore of Lake Geneva, near Lausanne. The German name Vivis is no longer commonly used.

It was the seat of the district of ...

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá offered a talk on the Baháʼí point of view on the immortality of soul and relationship of worlds and on the subject of divorce. He also met Horace Holley there. While in Thonon, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan

Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan ( fa, مسعود میرزا ظلالسلطان, "Mass'oud Mirza the Sultan's Shadow"; 5 January 1850 in Tabriz – 2 July 1918 in Isfahan), or Massud Mirza, was a Persian prince of the Qajar dynasty; he was know ...

, who had asked to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Soltan, who had ordered the execution of King and Beloved of martyrs, was the eldest grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar

Naser al-Din Shah Qajar ( fa, ناصرالدینشاه قاجار; 16 July 1831 – 1 May 1896) was the fourth Shah of Qajar Iran from 5 September 1848 to 1 May 1896 when he was assassinated. He was the son of Mohammad Shah Qajar and Mal ...

who had ordered the Execution of the Báb

On the morning of July 9, 1850 in Tabriz, a 30-year-old Persian merchant known as the Báb was charged with apostasy and shot by order of the Prime Minister of the Persian Empire. The events surrounding his execution have been the subject of co ...

himself. Juliet Thompson

Juliet Thompson (1873–1956) was an American painter, and disciple of Baháʼí Faith leader ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. She is perhaps best remembered for her book ''The Diary of Juliet Thompson'' though she also painted a life-sized portrait of ʻAbdu'l-Ba ...

, an American Baháʼí and artist who had also come to visit ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, shared comments of Hippolyte who heard Soltan's stammering apology for past wrongs. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá embraced him and invited his sons to lunch. Thus Bahram Mirza Sardar Mass'oud and Akbar Mass'oud, another grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, met with the Baháʼís, and apparently Akbar was greatly affected by meeting ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.

Great Britain

On 3 September ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left the shores of Lake Geneva travelling towardsLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

where he arrived on 4 September; he would stay in London until 23 September. While in London ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed at a residence of Lady Blomfield. On the first few days in London ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was interviewed by the editor of the ''Christian Commonwealth'', a weekly newspaper devoted to a liberal Christian theology. The editor was also present at a meeting of the Reverend Reginald John Campbell

Reginald John Campbell (29 August 1867 – 1 March 1956) was a British Congregationalist and Anglican divine who became a popular preacher while the minister at the City Temple and a leading exponent of 'The New Theology' movement of 1907. His ...

and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and wrote about the meeting in the 13 September edition of the ''Christian Commonwealth'' and the reprinted in the Star of the West Baháʼí magazine. After the meeting, the Reverend Reginald John Campbell asked ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to speak at City Temple.

Later in the month ʻAbdu'l-Bahá took a trip to Byfleet

Byfleet is a village in Surrey, England. It is located in the far east of the borough of Woking, around east of West Byfleet, from which it is separated by the M25 motorway and the Wey Navigation.

The village is of medieval origin. Its win ...

near Surrey where he visited Alice Buckton and Anett Schepel at their home. On the evening of 10 September he gave his first public talk in the Occident at City Temple The English translation was read by Wellesley Tudor Pole

Wellesley Tudor Pole OBE (23 April 1884 – 13 September 1968) was a spiritualist and early British Baháʼí.

He authored many pamphlets and books and was a lifelong pursuer of religious and mystical questions and visions, being particularl ...

and the talk was printed in the ''Christian Commonwealth'' newspaper on 13 September.

On 17 September, at the invitation of Albert Wilberforce, Archdeacon of Westminster, he addressed the congregation of Saint John the Divine, in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. He spoke on the subject of the kingdoms of mineral, vegetable, animal, humanity, and the Manifestations of God beneath God; Albert Wilberforce read the English translation himself. On the 28th ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to Byfleet again visiting Buckhorn and Schepel. He visited Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

on the 23rd–25th for several receptions and meetings though less public. On one such meeting he mentioned "When a thought of war enters your mind, suppress it, and plant in its stead a positive thought of peace." On the 30th he spoke to a Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, is a worldwide body with the aim to advance the ideas of Theosophy in continuation of previous Theosophists, especially the Greek and Alexandrian Neo-Platonic philosophers dating back to 3rd century CE ...

meeting with Annie Besant, Alfred Percy Sinnett

Alfred Percy Sinnett (18 January 1840 – 26 June 1921) was an English author and theosophist.

Biography

Sinnett was born in London. His father died while he was young, as in 1851 Sinnett was listed as a "Scholar – London University", liv ...

, Eric Hammond, who later published a volume on the religion in 1909. Back in London Alice Buckton visited Abdu'l-Bahá once again, and he went to Church House, Westminster to see a Christmas mystery play

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represe ...

titled ''Eager Heart'' that she had written.

From 23 to 25 September, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went to Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

where he met with many leading individuals including David Graham Pole, Claude Montefiore

Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore, also Goldsmid–Montefiore or just Goldsmid Montefiore (1858–1938) was the intellectual founder of Anglo- Liberal Judaism and the founding president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, a schola ...

, Alexander Whyte

''For the British colonial administrator, see Alexander Frederick Whyte''

Rev Alexander Whyte D.D.,LL.D. (13 January 18366 January 1921) was a Scottish divine. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in 1898.

...

, Lady Evelyn Moreton among others. Rev. Peter Z. Easton, a Presbyterian in the Synod of the Northeast

Synod of the Northeast is an upper judicatory of the Presbyterian Church (USA) based in East Syracuse, New York. The synod Presbyterian polity#The synod, oversees twenty-two presbyteries in six New England states (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Mas ...

in New York who was stationed in Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

, Iran from 1873 to 1880, didn't have an appointment to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Easton attempted to meet and challenge ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and in his actions made those around him uncomfortable; ʻAbdu'l-Bahá withdrew him to a private conversation and then he left. Later he printed a polemic attack on the religion, ''Bahaism — A Warning'', in the ''Evangelical Christendom'' newspaper of London (September–October 1911 edition.) The polemic was later responded to by Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl

Mírzá Muḥammad ( fa, ميرزا أبوالفضل), or Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl-i-Gulpáygání (1844–1914), was the foremost Baháʼí scholar who helped spread the Baháʼí Faith in Egypt, Turkmenistan, and the United States. He is one of ...

in his book ''The Brilliant Proof'' written in December 1911.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to London on 25 September, and a pastor of a Congregational church in the east end of London invited him to give an address on the following Sunday evening. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also visited to Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

where he met the higher Bible critic, Dr. Thomas Kelly Cheyne

Thomas Kelly Cheyne, (18 September 18411915) was an English divine and Biblical critic.

Biography

He was born in London and educated at Merchant Taylors' School, London, and Oxford University. Subsequently, he studied German theological methods ...

. Though ill, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá embraced him and praised his life's work. News of his activity in Britain was covered in New Zealand in a couple publications.

Ezra Pound met with him about the end of September, later explaining to Margaret Craven that Pound approached him like "an inquisition… and came away feeling that questions would been an impertinence…." The whole point is that they have ''done'' instead of talking, and a persian movement for religious unity that claims the feminine soul equal to the male… is worth while."On 1 October 1911, he returned to Bristol to perform a wedding of Baháʼís who had traveled from Persia and who brought humble gifts as well. On 3 October ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left London for

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, France.

France

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Paris for nine weeks, during which time he stayed at a residence at 4 Avenue de Camoens, and during his time there he was helped by Mr. Dreyfus-Barney and his wife, along with Lady Blomfield who had come from London. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first talk in Paris was on 16 October, and later that same day guests gathered in a poor quarter outside Paris at a home for orphans by Mr and Mrs. Ponsonaille which was much praised by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. From almost every day from 16 October to 26 November he gives talks. On a few of the days, he gave more than one talk. The book Paris Talks, part I, records transcripts of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks while he was in Paris for the first time. The substance of the volume is from notes Sara Louisa Blomfield, her two daughters and a friend. While most of his talks were held at his residence, he also gave talks at theTheosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, is a worldwide body with the aim to advance the ideas of Theosophy in continuation of previous Theosophists, especially the Greek and Alexandrian Neo-Platonic philosophers dating back to 3rd century CE ...

headquarters, at L'Alliance Spiritaliste, and on 26 November he spoke at Charles Wagner

Charles Wagner (4 January 1852 Vibersviller, Moselle – 12 May 1918)"Author of Popular Book, 'The Simple Life,' Dead" (May 14, 1918) ''Indianapolis Star'' was a French reformed pastor whose inspirational writings were influential in shaping t ...

's church ''Foyer de l-Ame''. He also met with various people including Muhammad ibn ʻAbdu'l-Vahhad-i Qazvini and Seyyed Hasan Taqizadeh

Sayyed Hasan Taqizādeh ( fa, سید حسن تقیزاده; September 27, 1878 in Tabriz, Iran – January 28, 1970 in Tehran, Iran) was an influential Iranian politician and diplomat, of Azeri origin, during the Qajar dynasty under the r ...

. It was during one of the meetings with Taqizadeh that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá personally first spoke on a telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

.

On 2 December 1911 ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left France, returning to Egypt.

Trip to North America

In the following year, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook a much more extensive journey to the United States and

In the following year, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook a much more extensive journey to the United States and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, ultimately visiting some 40 cities, to once again spread his father's teachings. He arrived in New York City on 11 April 1912. While he spent most of his time in New York, he visited many cities on the east coast. Then in August he started a more extensive journey across to the West coast before starting to return east at the end of October. On 5 December 1912 he set sail back to Europe. Several people, including ʻAbdu'l-Bahá himself, Dr. Allan L. Ward, author of ''239 Days'', and critic Samuel Graham Wilson have taken note of the uniqueness of this trip. Ward wrote: "... never before during the formative years of a religion has a figure of like stature made a journey of such magnitude in a setting so different from that of His native land." Wilson stated: "But Abdul Baha, except for Hindu Swamis, was the first Asiatic revelator America has received. Its hospitality showed up well. The public and press neither stoned the "prophet" nor caricatured him but looked with kindly eye upon the grave old man, in flowing oriental robes and white turban, with waving hoary hair and long white beard."

During his nine months on the continent, he met with David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University; Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise (March 17, 1874 – April 19, 1949) was an early 20th-century American Reform rabbi and Zionist leader in the Progressive Era. Born in Budapest, he was an infant when his family immigrated to New York. He followed his fath ...

of New York City; the inventor Alexander Graham Bell; Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

, the noted social worker; the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

, who was touring America at the time;Terry, Peter (1992, 2015) Rabindranath Tagore: Some Encounters with Baháʼís

'.

Herbert Putnam

George Herbert Putnam (September 20, 1861 – August 14, 1955) was an American librarian. He was the eighth (and also the longest-serving) Librarian of Congress from 1899 to 1939. He implemented his vision of a universal collection with strengt ...

, Librarian of Congress; the industrialist and humanitarian Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

; Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, president of the American Federation of Labor; the Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary; as well as hundreds of American and Canadian Baháʼís, recent converts to the religion.

A large number of memoirs cover this periodTranscripts of many talks given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in the US and Canada can be found in:

*

Other memoirs covering the period include:

*

*

*

*

*

*

Special mention should note the book ''239 Days; ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Journey in America '' by Dr. Allan L. Ward which brings together various references including newspapers, magazines, and memoirs for a detailed review of this period. The book builds on Ward's 1960 PhD dissertation.

*

*

Ward also presented at the 5th Annual Canadian ''Association for Baháʼí Studies'' with a talk titled "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and the American Press" and also published a number of essays in World Order Magazine, a Baháʼí serial, at least 3 times from 1968 to 1972.

*

*

as well as a wide array of newspaper stories.

On the RMS Cedric

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá boarded theRMS Cedric

RMS ''Cedric'' was an ocean liner owned by the White Star Line. She was the second of a quartet of ships over 20,000 tons, dubbed the Big Four, and was the largest vessel in the world at the time of her entering service. Her career, peppered w ...

in Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

bound for Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

on 25 March 1912. Others with him included Shoghi Effendi

Shoghí Effendi (; 1 March 1897 – 4 November 1957) was the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, appointed to the role of Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957. He created a series of teaching plans that over ...

, Asadu'lláh-i-Qumí, Dr Amínu'lláh Faríd, Mírzá Munír-i-Zayn, Áqá Khusraw, and Mahmúd-i-Zarqání. During the voyage a member of the Unitarians onboard requested if ʻAbdu'l-Bahá would send a message to them. He replied with a message announcing "… Glad tidings, glad tidings, the Herald of the Kingdom has raised His voice." Through several conversations it was arranged by several passengers that he address a larger audience on the ship. The ship arrived in Naples harbour on 28 March 1912, and on the next day several Baháʼís from America and Britain boarded the ship. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and his group did not disembark for fear of being confused with Turks during the ongoing Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

. Shoghi Effendi and two others were refused further passage by reason of a minor illness and were taken ashore. Though all were not convinced of the sincerity of the diagnosis and some presumed it was ill will against the voyagers as if they were Turkish.

The American Baháʼí community had sent thousands of dollars urging ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to leave the Cedric in Italy and travel to England to sail on the maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United ...

. Instead he returned the money for charity and continued the voyage on the Cedric. From Naples, the group sailed on to New York — the group included ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Asadu'lláh-i-Qumí, Dr Amínu'lláh Faríd, Mahmúd-i-Zarqání, Mr and Mrs Percy Woodcock and their daughter from Canada, Mr and Mrs Austin from Denver, Colorado, and Miss Louisa Mathew. Other notables aboard included at least two Italian embassy officials; note ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was listed as an "author" on immigration paperwork. They passed Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on 3 April onward to New York. Many letters and telegrams were sent and received during the voyage as well as various tablets written.

New England

The SS Cedric arrived in New York harbour on the morning of 11 April and telegrams were sent and received from Baháʼí local spiritual assemblies to announce his safe arrival while the passengers were processed for quarantine. Baháʼís who had gathered at the port were generally sent to gather at a home where ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was to visit later. Reporters interviewed him while he was on board and he elaborated on the trip and his goals. However a few Baháʼís, including Marjorie Morten, Rhoda Nichols andJuliet Thompson

Juliet Thompson (1873–1956) was an American painter, and disciple of Baháʼí Faith leader ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. She is perhaps best remembered for her book ''The Diary of Juliet Thompson'' though she also painted a life-sized portrait of ʻAbdu'l-Ba ...

, hid themselves to catch a glimpse of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. His arrival in New York was covered by various different newspapers including the New York Tribune and the Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large na ...

.

While in New York he stayed at The Ansonia

The Ansonia is a building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City, located at 2109 Broadway, between 73rd and 74th Streets. It was originally built as a residential hotel by William Earle Dodge Stokes, the Phelps-Dodge copper heir ...

hotel. Several blocks to the north west of the hotel was the residence of Edward B. Kinney, where ʻAbdu'l-Bahá held his first meeting with the American Baháʼís; his next talk was at given at Howard MacNutt's residence. From 11 April until 25 April he gave at least one talk a day and most mornings and afternoons were spent meeting often one by one with visitors coming to his residence. During ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's time in New York, Lua Getsinger

Louise Aurora Getsinger (1 November 1871, Hume, New York – 2 May 1916, Cairo, Egypt), known as Lua, was one of the first Western members of the Baháʼí Faith, recognized as joining the religion on May 21, 1897, just two years after Thornt ...

helped correspond with various Baháʼís about ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's plans as they evolved.

Rev. Percy Stickney Grant, through association with Juliet Thompson

Juliet Thompson (1873–1956) was an American painter, and disciple of Baháʼí Faith leader ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. She is perhaps best remembered for her book ''The Diary of Juliet Thompson'' though she also painted a life-sized portrait of ʻAbdu'l-Ba ...

, invited ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to speak at Church of the Ascension on the evening of 14 April. The event was covered by the New York Times, the '' New York Tribune'', and the ''Washington Post''. The event caused a stir because, while there were rules in the Episcopal Church Canon forbidding someone of another ordination from preaching from the pulpit without the consent of the bishop, there was no provision against a non-ordained person offering prayer in the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ov ...

.

Mary Williams, also known as Kate Carew

Mary Williams (June 27, 1869 – February 11, 1961), who wrote pseudonymously as Kate Carew, was an American caricaturist self-styled as "The Only Woman Caricaturist". She worked at the ''New York World'', providing illustrated celebrity int ...

, known for her caricatures, was among those who visited ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and travelled with him for a number of days. On 16 April, with Mary Williams still travelling with him, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited the Bowery

The Bowery () is a street and neighborhood in Lower Manhattan in New York City. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th Street in the north.Jackson, Kenneth L. ...

. Mary Williams noted that she was impressed with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's generosity of spirit in bringing people of social standing to the Bowery as well as that he then gave money to the poor. Some boys were reported to heckle the event but were invited afterwards for a personal meeting. At this meeting, after greeting all the boys, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá singled out an African-American boy and compared him to a black rose as well as rich chocolate.

In Boston newspaper reporters asked ʻAbdu'l-Bahá why he had come to America, and he stated that he had come to participate in conferences on peace and that just giving warning messages is not enough. A full page summary of the religion was printed in the New York Times. A booklet on the religion was published late April.

On 20 April ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left New York and travelled to Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

where he stayed until 28 April. While in Washington D.C. a number of meetings and notable events took place. On 23 April ʻAbdu'l-Bahá attended several events; first he spoke at Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

to over 1000 students, faculty, administrators and visitors — an event commemorated in 2009. Then he attended a reception by the Persian Charg-de-Affairs and the Turkish Ambassador; at this reception ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved the place-names such that the only African-American present, Louis George Gregory, was seated at the head of the table next to himself. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also welcomed William Sulzer

William Sulzer (March 18, 1863 – November 6, 1941) was an American lawyer and politician, nicknamed Plain Bill Sulzer. He was the 39th Governor of New York and a long-serving congressman from the same state.

Sulzer was the first, and to date ...

, then a Democratic Congressman and later Governor from New York, as well as Champ Clark

James Beauchamp Clark (March 7, 1850March 2, 1921) was an American politician and attorney who represented Missouri in the United States House of Representatives and served as Speaker of the House from 1911 to 1919.

Born in Kentucky, he establis ...

, then Speaker of the House of Representatives.Note Sulzer would go on to write expansively of the Baha'i Faith as he understood it:

*

*

Later during his stay in Washington, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at Bethel Literary and Historical Society, the leading African-American institution of Washington DC. The talk had been planned out by the end of March due to the work of Louis Gregory. While in Washington ʻAbdu'l-Bahá continued to speak from the Parson's home to individuals and groups. A Methodist minister suggested some of his listeners should teach him Christianity, though also judged him sincere.

Mid-West

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

on 29 April, though later than anticipated as he had hoped to be in Chicago in time for the American Baháʼí national convention. While in Chicago ʻAbdu'l-Bahá attended the last session of the newly founded Baháʼí Temple Unity, and laid the dedication stone of the Baháʼí House of Worship

A Baháʼí House of Worship or Baháʼí temple is a place of worship of the Baháʼí Faith. It is also referred to by the name ''Mashriqu'l-Adhkár'', which is Arabic for "Dawning-place of the remembrance of God". Baháʼí Houses of Worshi ...

near Chicago.

Robert Sengstacke Abbott

Robert Sengstacke Abbott (December 24, 1870 – February 29, 1940) was an American lawyer, newspaper publisher and editor. Abbott founded ''The Chicago Defender'' in 1905, which grew to have the highest circulation of any black-owned newspaper i ...

, an African American lawyer and newspaper publisher, met ʻAbdu'l-Bahá when covering a talk of his during his stay in Chicago at Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

' Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Cha ...

. He would later become a Baháʼí in 1934. Also while ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was in Chicago, the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&n ...

's print magazine ''The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

'' printed an article introducing the religion to their readers, and later in June noted ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talk at their fourth national convention.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Chicago on 6 May and went to Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

where he stayed until the 7th. Though Saichiro Fujita , a native of Yamaguchi Prefecture, was the second Japanese to become a member of the Baháʼí Faith from Japan. He was also distinguished by serving for many years at the Baháʼí World Centre through many of the heads of the religion from the ti ...

, one of the first Baháʼís of Japanese descent, was living in Cleveland working for a Dr Barton-Peek, a female Baháʼí, he failed to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as he came through. He was able to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá later during his further travels. In Cleveland ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at his hotel twice and was interviewed by newspaper reporters. Among some who met ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Cleveland included Louise Gregory, and Alain Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke (September 13, 1885 – June 9, 1954) was an American writer, philosopher, educator, and patron of the arts. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect ...

.

On 7 May ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went to Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

where a speaking engagement was arranged for him in early April through the efforts of Martha Root

Martha Louise Root (August 10, 1872 – September 28, 1939) was an American traveling teacher of the Baháʼí Faith in the early 20th century. From the declaration of her belief in 1909 until her death thirty years later, she went around the ...

. He stayed in Pittsburgh for one day before going back to Washington D.C on 8 May 1912.

Back to North East

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Washington DC from 8 to 11 May, when he then returned to the New York City area. On 12 May he visited Montclair, NJ, and then on 14 May he went to northern

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Washington DC from 8 to 11 May, when he then returned to the New York City area. On 12 May he visited Montclair, NJ, and then on 14 May he went to northern New York state

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. stat ...

to Lake Mohonk

Lake Mohonk is a lake in Ulster County, New York, United States. It is located approximately northwest of Poughkeepsie. Activities on the lake are operated by Mohonk Mountain House.

Description

The small lake, long and deep, is located above ...

where he addressed the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration and stayed at the Mohonk Mountain House

The Mohonk Mountain House, also known as Lake Mohonk Mountain House, is an American resort hotel located south of the Catskill Mountains on the crest of the Shawangunk Ridge. The property lies at the junction of the towns of New Paltz, Marbletow ...

.

His talk was covered by many publications, and began "When we consider history, we find that civilization is progressing, but in this century its progress cannot be compared with that of past centuries. This is the century of light and of bounty. In the past, the unity of patriotism, the unity of nations and religions was established; but in this century, the oneness of the world of humanity is established; hence this century is greater than the past."In the rest of his talk he outlined a brief history of religious conflict, spoke about some of the

Baháʼí teachings

The Baháʼí teachings represent a considerable number of theological, ethical, social, and spiritual ideas that were established in the Baháʼí Faith by Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion, and clarified by its successive leaders: ʻA ...

including the oneness of humanity, the complementary role of religion and science, the equality of women and men, the abolition of the extremes of wealth and poverty, and that humanity needs more than philosophy — that it needs the breadth of the Holy Spirit. A reverend heard his presentation and invited him and introduced him at a reception at another event on 28 May. Elbert Hubbard

Elbert Green Hubbard (June 19, 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American writer, publisher, artist, and philosopher. Raised in Hudson, Illinois, he had early success as a traveling salesman for the Larkin Soap Company. Hubbard is known best as th ...

, an American writer, also noted ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talk at the Mohonk conference. Samuel Chiles Mitchell, then President at the University of South Carolina was present and affected by his presentation. Through correspondence with Gregory, Gregory came to the view that Mitchell had repeated ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's words "upon many platforms."

After the conference, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to New York City, where he stayed until the 22nd, leaving to the Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

area for four days including a trip to Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

on the 23rd. On 26 May he returned to New York City, where he would remain for most of his time until 20 June. He took short trips to Fanwood, New Jersey

Fanwood is a borough in Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 7,774, an increase of 456 (+6.2%) from the 2010 census count of 7,318, which in turn reflected an increa ...

, from 31 May to 1 June, to Milford, Pennsylvania

Milford is a borough in Pike County, Pennsylvania and the county seat. Its population was 1,103 at the 2020 census. Located on the upper Delaware River, Milford is part of the New York metropolitan area.

History

The area along the Delaware R ...

, on 3 June, and to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

from 8 to 10 June, always returning to New York City.

On 18 June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá hosted a meeting at the MacNutt's home for the purpose of being filmed and recorded. This film was the second time that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was filmed,The first film was by a production company that asked if they could film him for few minutes to appear in a newsreel

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, inform ...

the first week he arrived He agreed over the objection of the Baháʼís who felt the process was not socially proper. This first film was incorporated into a 1985 documentary by the BBC TV unit in 1985 called "The Quiet Revolution" as part of the "Everyman" TV series. and was done by Baháʼís at the home of Howard MacNutt. The film recorded at the MacNutt residence was released as a short movie called "Servant of Glory".

Over several days starting on 1 June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá sat for a life-sized portrait by Juliet Thompson

Juliet Thompson (1873–1956) was an American painter, and disciple of Baháʼí Faith leader ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. She is perhaps best remembered for her book ''The Diary of Juliet Thompson'' though she also painted a life-sized portrait of ʻAbdu'l-Ba ...

. During that time Thompson witnessed Lua Getsinger

Louise Aurora Getsinger (1 November 1871, Hume, New York – 2 May 1916, Cairo, Egypt), known as Lua, was one of the first Western members of the Baháʼí Faith, recognized as joining the religion on May 21, 1897, just two years after Thornt ...

given the task of conveying ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's message that New York was the ''City of the Covenant''; when the group moved into the rest of the house Getsinger made the announcement.

Later in the month, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited Montclair, New Jersey

Montclair () is a township in Essex County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Situated on the cliffs of the Watchung Mountains, Montclair is a wealthy and diverse commuter town and suburb of New York City within the New York metropolitan area. ...

from 20 to 25 June, coming back to New York until 29 June. On 29 and 30 June he visited West Englewood, NJ which is now Teaneck

Teaneck () is a township in Bergen County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is a bedroom community in the New York metropolitan area. As of the 2010 U.S. census, the township's population was 39,776, reflecting an increase of 516 (+1.3%) f ...

and attended a ''Unity Feast'' similar to a Nineteen Day Feast where Baháʼís, Jews, Muslims, Christians, Caucasians, African-Americans, and Persians attended. Among those that attended the event was Martha Root

Martha Louise Root (August 10, 1872 – September 28, 1939) was an American traveling teacher of the Baháʼí Faith in the early 20th century. From the declaration of her belief in 1909 until her death thirty years later, she went around the ...

. For her it was a high point in her life and has since been commemorized as ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's "Souvenir Picnic". It is at this event that Lua Getsinger

Louise Aurora Getsinger (1 November 1871, Hume, New York – 2 May 1916, Cairo, Egypt), known as Lua, was one of the first Western members of the Baháʼí Faith, recognized as joining the religion on May 21, 1897, just two years after Thornt ...

intentionally walked through poison ivy hoping to make her incapable of leaving the presence of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá when he asked her to travel ahead of him to California. Today the property is known as the Wilhelm Baháʼí Properties.

His further travels took him to Morristown, New Jersey on 30 June and he then went back to New York for a nearly a month from 30 June to 23 July, with a sojourn in West Englewood, NJ on 14 July. Starting on 23 June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went to New England on his way to Canada in late August. He stayed in Boston for 23 and 24 July, and then went to the summer home of Mr. and Mrs. Parsons in Dublin, New Hampshire

Dublin is a town in Cheshire County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,532 at the 2020 census. It is home to Dublin School and ''Yankee'' magazine.

History

In 1749, the Masonian proprietors granted the town as "Monadnock No. ...

from 24 July to 16 Aug. He then went to Eliot, Maine

Eliot is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Originally settled in 1623, it was formerly a part of Kittery, Maine, to its east. After Kittery, it is the next most southern town in the state of Maine, lying on the Piscataqua River across f ...

from 16 to 23 Aug, where he stayed in Green Acre

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by a combina ...

which was then a conference facility, and which since has become a Baháʼí school. His final destination in New England was Malden, Massachusetts where he stayed from 23 to 29 August.

Trip to Canada

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had mentioned an intention of visitingMontreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

as early as February 1912 and in August a phone number was listed for inquirers to arrange appointments for his visit there. He left to Boston and then rode to Montreal where he arrived near midnight on 30 August 1912 at the Windsor train station on Peel Street and was greeted by William Sutherland Maxwell

William Sutherland Maxwell (November 14, 1874 – March 25, 1952) was a well-known Canadian architect and a Hand of the Cause in the Baháʼí Faith. He was born in Montreal, Quebec, Canada to parents Edward John Maxwell and Johan MacBean.

Lif ...

. He would stay in Montreal until 9 September. On his first day in the city he was visited by Frederick Robertson Griffin who would later lead the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia. Later that morning he visited a friend of the Maxwell's who had a sick baby. In the afternoon he took a car ride around Montreal. That evening a reception was held including a local socialist leader. The next day he spoke at a Unitarian church on Sherbrooke Street

Sherbrooke Street (officially in french: rue Sherbrooke) is a major east–west artery and at in length, is the second longest street on the Island of Montreal. The street begins in the town of Montreal West and ends on the extreme tip of ...

. Anne Savage recorded that she had sought him out but uncharacteristically was shy upon seeing him. He took up residence in the Windsor Hotel. The next day William Peterson, then Principal of McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous ...

visited him. After a day of meeting individuals he took an afternoon excursion on his own possibly to the francophone part of the city and back. That evening he spoke to a socialist meeting addressing "The Economic Happiness of the Human Race" — that we are as one family and should care for each other, not to have absolute equality but to have a firm minimum even for the poorest, to note foremost the position of the farmer, and a progressive tax

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases.Sommerfeld, Ray M., Silvia A. Madeo, Kenneth E. Anderson, Betty R. Jackson (1992), ''Concepts of Taxation'', Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX The term ''progre ...

system. The next day he rode the Mountain Elevator of Montreal The next day Paul Bruchési Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Montreal

The Archdiocese of Montréal ( la, Archdioecesis Marianopolitana) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Canada. A metropolitan see, its archepiscopal see is the Montreal, Quebec. It includes Montreal a ...

visited him and later he spoke at the Saint James United Church

, image = Église St James Mtl.jpg

, imagesize =

, imagealt =

, caption = St. James United Church on Saint Catherine Street in Downtown Montreal.

, pushpin map = Montreal ...

; his talk outlined a comprehensive review of the Baháʼí teachings

The Baháʼí teachings represent a considerable number of theological, ethical, social, and spiritual ideas that were established in the Baháʼí Faith by Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion, and clarified by its successive leaders: ʻA ...

. Afterwards he said:I find these two great American nations highly capable and advanced in all that appertains to progress and civilization. These governments are fair and equitable. The motives and purposes of these people are lofty and inspiring. Therefore, it is my hope that these revered nations may become prominent factors in the establishment of international peace and the oneness of the world of humanity; that they may lay the foundations of equality and spiritual brotherhood among mankind; that they may manifest the highest virtues of the human world, revere the divine lights of the Prophets of God and establish the reality of unity so necessary today in the affairs of nations. I pray that the nations of the East and West shall become one flock under the care and guidance of the divine Shepherd. Verily, this is the bestowal of God and the greatest honor of man. This is the glory of humanity. This is the good pleasure of God. I ask God for this with a contrite heart.ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit to Montreal provided notable newspaper coverage; on the night of his arrival the editor of the ''

Montreal Daily Star

''The Montreal Star'' was an English-language Canadian newspaper published in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It closed in 1979 in the wake of an eight-month pressmen's strike.

It was Canada's largest newspaper until the 1950s and remained the dominan ...

'' met with him and that newspaper along with The Montreal Gazette

The ''Montreal Gazette'', formerly titled ''The Gazette'', is the only English-language daily newspaper published in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Three other daily English-language newspapers shuttered at various times during the second half of th ...

, ''Montreal Standard'', Le Devoir

''Le Devoir'' (, "Duty") is a French-language newspaper published in Montreal and distributed in Quebec and throughout Canada. It was founded by journalist and politician Henri Bourassa in 1910.

''Le Devoir'' is one of few independent large-c ...

and La Presse among others reported on ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's activities. The headlines in those papers included "Persian Teacher to Preach Peace", "Racialism Wrong, Says Eastern Sage, Strife and War Caused by Religious and National Prejudices", and "Apostle of Peace Meets Socialists, Abdul Baha's Novel Scheme for Distribution of Surplus Wealth." The ''Montreal Standard'', which was distributed across Canada, took so much interest that it republished the articles a week later; the Gazette published six articles and Montreal's largest French language newspaper published two articles about him. The ''Harbor Grace Standard'' newspaper, of Harbour Grace

Harbour Grace is a town in Conception Bay on the Avalon Peninsula in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. With roots dating back to the 16th century, it is one of the oldest towns in North America.

It is located about northwest of ...

, Newfoundland, printed a story summarizing several of his talks and trips. After he left the country, the ''Winnipeg Free Press'' highlighted his position on the equality of women and men. All together some accounts of his talks and trips would reach 440,000 in French and English coverage. He travelled through several villages on the way back to the States.

Travel to the West coast

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Canada and started his travel to the American West coast stopping in multiple places in the country during his travels. From 9 September through 12th he stayed inBuffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, where he made a fleeting visit to Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Fall ...

on 12 September. He then travelled to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

(12–15 September), Kenosha, Wisconsin

Kenosha () is a city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the seat of Kenosha County. Per the 2020 census, the population was 99,986 which made it the fourth-largest city in Wisconsin. Situated on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan, Kenos ...

(15–16 September), back to Chicago on 16 September, and then to Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

where he stayed from 16 to 21 September.

His further travels took him to Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

(21 September), Lincoln, Nebraska

Lincoln is the capital city of the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Lancaster County. The city covers with a population of 292,657 in 2021. It is the second-most populous city in Nebraska and the 73rd-largest in the United Sta ...

(23 September), Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Colorado ( 24–27 September), Glenwood Springs, Colorado

Glenwood Springs is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Home rule municipality, home rule municipality that is the county seat of Garfield County, Colorado, Garfield County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 9,963 at the 2020 Uni ...

(28 September), and Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

(29–30 September). In Salt Lake City, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, accompanied by his translators, Saichiro Fujita , a native of Yamaguchi Prefecture, was the second Japanese to become a member of the Baháʼí Faith from Japan. He was also distinguished by serving for many years at the Baháʼí World Centre through many of the heads of the religion from the ti ...

and others attended the Utah State Fair and visited the Mormon Tabernacle. During the Mormon's annual convention, at the steps of the Temple, he was reported to have said: "They built me a temple but they will not let me in!" He left the next day and travelled by railcar to San Francisco, on what was then the Central Pacific Railroad, through Reno. Traveling all day through Nevada on its way to California, the train made regular stops but there's no record of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá disembarking until his arrival in San Francisco. While traversing the Sierra Nevada, he made a reference to observing the snow sheds at Donner Pass

Donner Pass is a mountain pass in the northern Sierra Nevada, above Donner Lake and Donner Memorial State Park about west of Truckee, California. Like the Sierra Nevada themselves, the pass has a steep approach from the east and a gradual appr ...

and the struggle of the pioneering members of the Donner Party

The Donner Party, sometimes called the Donner–Reed Party, was a group of American pioneers who migrated to California in a wagon train from the Midwest. Delayed by a multitude of mishaps, they spent the winter of 1846–1847 snowbound in th ...

.

California

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived inSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

on 4 October. During his visit to California he mostly stayed in Bay Area including from 4–13 October, 16–18 October, 21–25 October with shorter trips to Pleasanton from 13 to 16 October, to Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

from 18–21 October and to Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

from 25–26 October While in San Francisco, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at Stanford University on 8 October, and at Temple Emmanuel-El on 12 October.

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Los Angeles he went to the Hotel Lankershim

The Hotel Lankershim was a landmark hotel located at Seventh Street and Broadway (Los Angeles), Broadway in downtown Los Angeles, California in the United States. Construction began in 1902 and was completed in 1905. The building was largely demoli ...

, where he would reside during his stay, and where he would later give a talk. On his first full day in Los Angeles ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, along with twenty-five other Baháʼís, visited Thornton Chase's grave on 19 October. Thornton Chase was the first American Baháʼí, and he had only recently moved to Los Angeles and helped form the first Local Spiritual Assembly

Spiritual Assembly is a term given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to refer to elected councils that govern the Baháʼí Faith. Because the Baháʼí Faith has no clergy, they carry out the affairs of the community. In addition to existing at the local level ...

in the city. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was eager to meet Thornton Chase, but Chase died on the evening of 30 September shortly before ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in California on 4 October. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá designated Chase's grave a place of pilgrimage, and revealed a tablet of visitation, which is a prayer to say in remembrance of a person, and decreed that his death be commemorated annually.

Back across America

After his visit to California, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá started his trip back to the East coast. On his way back he stopped inDenver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

(28–29 October), Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

(31 October – 3 November) and Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

(5–6 November) before arriving in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

on 6 November. In Washington he was invited to speak to the Washington Hebrew Congregation

Washington Hebrew Congregation (WHC) is a Reform Jewish synagogue in Washington, D.C. Washington Hebrew Congregation is currently a member of the Union for Reform Judaism. It is one of the largest Reform congregations in the United States, with 2,7 ...

at their temple on 9 November.

Later on 11 November, he travelled to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, where his arrival was anticipated from early April, and he spoke at a Unitarian church saying in part that "the world looked to America as the leader in the world-wide peace movement" and "not being a rival of any other power and not considering colonization schemes or conquests, made it an ideal country to lead the movement." On the same day he travelled to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...