Tropospheric scatter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tropospheric scatter, also known as troposcatter, is a method of communicating with microwave radio signals over considerable distances – often up to and further depending on frequency of operation, equipment type, terrain, and climate factors. This method of propagation uses the tropospheric scatter phenomenon, where radio waves at

Tropospheric scatter, also known as troposcatter, is a method of communicating with microwave radio signals over considerable distances – often up to and further depending on frequency of operation, equipment type, terrain, and climate factors. This method of propagation uses the tropospheric scatter phenomenon, where radio waves at

The

The

Tropospheric scatter, also known as troposcatter, is a method of communicating with microwave radio signals over considerable distances – often up to and further depending on frequency of operation, equipment type, terrain, and climate factors. This method of propagation uses the tropospheric scatter phenomenon, where radio waves at

Tropospheric scatter, also known as troposcatter, is a method of communicating with microwave radio signals over considerable distances – often up to and further depending on frequency of operation, equipment type, terrain, and climate factors. This method of propagation uses the tropospheric scatter phenomenon, where radio waves at UHF

Ultra high frequency (UHF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies in the range between 300 megahertz (MHz) and 3 gigahertz (GHz), also known as the decimetre band as the wavelengths range from one meter to one tenth of a meter (on ...

and SHF frequencies

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is e ...

are randomly scattered as they pass through the upper layers of the troposphere

The troposphere is the first and lowest layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, and contains 75% of the total mass of the planetary atmosphere, 99% of the total mass of water vapour and aerosols, and is where most weather phenomena occur. Fro ...

. Radio signals are transmitted in a narrow beam aimed just above the horizon in the direction of the receiver station. As the signals pass through the troposphere, some of the energy is scattered back toward the Earth, allowing the receiver station to pick up the signal.

Normally, signals in the microwave frequency range travel in straight lines, and so are limited to '' line-of-sight'' applications, in which the receiver can be 'seen' by the transmitter. Communication distances are limited by the visual horizon to around . Troposcatter allows microwave communication beyond the horizon. It was developed in the 1950s and used for military communications until communications satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Earth ...

s largely replaced it in the 1970s.

Because the troposphere is turbulent and has a high proportion of moisture, the tropospheric scatter radio signals are refracted

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomeno ...

and consequently only a tiny proportion of the transmitted radio energy is collected by the receiving antennas. Frequencies of transmission around are best suited for tropospheric scatter systems as at this frequency the wavelength of the signal interacts well with the moist, turbulent areas of the troposphere, improving signal-to-noise ratio

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR or S/N) is a measure used in science and engineering that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. SNR is defined as the ratio of signal power to the noise power, often expressed in de ...

s.

Overview

Discovery

Previous toWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, prevailing radio physics theory predicted a relationship between frequency and diffraction that suggested radio signals would follow the curvature of the Earth, but that the strength of the effect would fall off rapidly and especially at higher frequencies. However, during the war, there were numerous incidents in which high-frequency radar signals were able to detect targets at ranges far beyond the theoretical calculations. In spite of these repeated instances of anomalous range, the matter was never seriously studied.

In the immediate post-war era, the limitation on television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

construction was lifted in the United States and millions of sets were sold. This drove an equally rapid expansion of new television stations. Based on the same calculations used during the war, the Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains jurisdicti ...

(FCC) arranged frequency allocations for the new VHF and UHF channels to avoid interference between stations. To everyone's surprise, interference was common, even between widely separated stations. As a result, licenses for new stations were put on hold in what is known as the "television freeze" of 1948.

Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mul ...

was among the many organizations that began studying this effect, and concluded it was a previously unknown type of reflection off the tropopause. This was limited to higher frequencies, in the UHF and microwave bands, which is why it had not been seen prior to the war when these frequencies were beyond the ability of existing electronics. Although the vast majority of the signal went through the troposphere and on to space, the tiny amount that was reflected was useful if combined with powerful transmitters and very sensitive receivers. In 1952, Bell began experiments with Lincoln Labs

The MIT Lincoln Laboratory, located in Lexington, Massachusetts, is a United States Department of Defense federally funded research and development center chartered to apply advanced technology to problems of national security. Research and dev ...

, the MIT-affiliated radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

research lab. Using Lincoln's powerful microwave transmitters and Bell's sensitive receivers, they built several experimental systems to test a variety of frequencies and weather effects. When Bell Canada

Bell Canada (commonly referred to as Bell) is a Canadian telecommunications company headquartered at 1 Carrefour Alexander-Graham-Bell in the borough of Verdun in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is an ILEC (incumbent local exchange carrier) in ...

heard of the system they felt it might be useful for a new communications network in Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

and took one of the systems there for cold weather testing.

In 1954 the results from both test series were complete and construction began on the first troposcatter system, the Pole Vault

Pole vaulting, also known as pole jumping, is a track and field event in which an athlete uses a long and flexible pole, usually made from fiberglass or carbon fiber, as an aid to jump over a bar. Pole jumping competitions were known to the M ...

system that linked Pinetree Line radar systems along the coast of Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

. Using troposcatter reduced the number of stations from 50 microwave relays scatted through the wilderness to only 10, all located at the radar stations. In spite of their higher unit costs, the new network cost half as much to build as a relay system. Pole Vault was quickly followed by similar systems like White Alice

The White Alice Communications System (WACS, "White Alice" colloquially) was a United States Air Force telecommunication network with 80 radio stations constructed in Alaska during the Cold War. It used tropospheric scatter for over-the-horizon l ...

, relays on the Mid-Canada Line and the DEW Line

The Distant Early Warning Line, also known as the DEW Line or Early Warning Line, was a system of radar stations in the northern Arctic region of Canada, with additional stations along the north coast and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (see Proj ...

, and during the 1960s, across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and Europe as part of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

's ACE High

Allied Command Europe Highband, better known as ACE High, was a fixed service NATO radiocommunication and early warning system dating back to 1956. After extensive testing ACE High was accepted by NATO to become operational in 1964/1965.

The fr ...

system.

Use

The

The propagation loss In underwater acoustics, propagation loss is a measure of the reduction in sound intensity as the sound propagates away from an underwater sound source. It is defined as the difference between the source level and the received sound pressure level ...

es are very high; only about one trillionth () of the transmit power is available at the receiver. This demands the use of antennas with extremely large antenna gain

In electromagnetics, an antenna's gain is a key performance parameter which combines the antenna's directivity and radiation efficiency. The term ''power gain'' has been deprecated by IEEE. In a transmitting antenna, the gain describes ho ...

. The original Pole Vault system used large parabolic reflector

A parabolic (or paraboloid or paraboloidal) reflector (or dish or mirror) is a reflective surface used to collect or project energy such as light, sound, or radio waves. Its shape is part of a circular paraboloid, that is, the surface genera ...

dish antennas, but these were soon replaced by billboard antennas which were somewhat more robust, an important quality given that these systems were often found in harsh locales. Paths were established at distances over . They required antennas ranging from and amplifiers ranging from to . These were analogue systems which were capable of transmitting a few voice channels.

Troposcatter systems have evolved over the years. With communication satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Eart ...

s used for long-distance communication links, current troposcatter systems are employed over shorter distances than previous systems, use smaller antennas and amplifiers, and have much higher bandwidth capabilities. Typical distances are between , though greater distances can be achieved depending on the climate, terrain, and data rate required. Typical antenna sizes range from while typical amplifier sizes range from to . Data rates over can be achieved with today's technology.

Tropospheric scatter is a fairly secure method of propagation as dish alignment is critical, making it extremely difficult to intercept the signals, especially if transmitted across open water, making them highly attractive to military users. Military systems have tended to be ‘thin-line’ tropo – so called because only a narrow bandwidth ‘information’ channel was carried on the tropo system; generally up to 32 analogue ( bandwidth) channels. Modern military systems are "wideband" as they operate 4-16 Mbit/s digital data channels.

Civilian troposcatter systems, such as the British Telecom

BT Group plc (trading as BT and formerly British Telecom) is a British multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered in London, England. It has operations in around 180 countries and is the largest provider of fixed-line, b ...

(BT) North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

oil communications network, required higher capacity ‘information’ channels than were available using HF (high frequency – to ) radio signals, before satellite technology was available. The BT systems, based at Scousburgh

Scousburgh is a small community in the parish of Dunrossness, in the South Mainland of Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Island ...

in the Shetland Islands

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

, Mormond Hill

Mormond Hill (Scottish Gaelic A' Mhormhonadh, meaning the great hill or moor; known as ''Mormounth'' in Old Scots) is a large hill in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, not far from Fraserburgh. Its peak is .Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially different boundaries. The Aberdeenshire Council area inclu ...

and Row Brow near Scarborough, were capable of transmitting and receiving 156 analogue ( bandwidth) channels of data and telephony to / from North Sea oil production platforms, using frequency-division multiplexing

In telecommunications, frequency-division multiplexing (FDM) is a technique by which the total bandwidth available in a communication medium is divided into a series of non-overlapping frequency bands, each of which is used to carry a separat ...

(FDMX) to combine the channels.

Because of the nature of the turbulence in the troposphere, quadruple diversity propagation paths were used to ensure reliability of the service, equating to about 3 minutes of downtime due to propagation drop out per month. The quadruple space and polarisation diversity systems needed two separate dish antennas (spaced several metres apart) and two differently polarised feed horn

A feed horn (or feedhorn) is a small horn antenna used to couple a waveguide to e.g. a parabolic dish antenna or offset dish antenna for reception or transmission of microwave. A typical application is the use for satellite television ...

s – one using vertical polarisation, the other using horizontal polarisation. This ensured that at least one signal path was open at any one time. The signals from the four different paths were recombined in the receiver where a phase corrector removed the phase differences of each signal. Phase differences were caused by the different path lengths of each signal from transmitter to receiver. Once phase corrected, the four signals could be combined additively.

Tropospheric scatter communications networks

The tropospheric scatter phenomenon has been used to build both civilian and military communication links in a number of parts of the world, including: ; Allied Command Europe Highband (ACE High), :NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

military radiocommunication

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

and early warning system throughout Europe from the Norwegian-Soviet border to the Turkish-Soviet border.

; BT (British Telecom),

:United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

- Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

to Mormond Hill

Mormond Hill (Scottish Gaelic A' Mhormhonadh, meaning the great hill or moor; known as ''Mormounth'' in Old Scots) is a large hill in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, not far from Fraserburgh. Its peak is .Fernmeldeturm Berlin,

:Torfhaus-Berlin, Clenze-Berlin at Cold War times

; Portugal Telecom,

:Serra de Nogueira (northeastern Portugal) to Artzamendi (southwestern France)

; CNCP Telecommunications,

: Tsiigehtchic to Galena Hill, Keno City

: :A Warsaw Pact tropo-scatter network stretching from near

:A Warsaw Pact tropo-scatter network stretching from near  :A single section from

:A single section from

The U.S. Army and Air Force use tactical tropospheric scatter systems developed by

The U.S. Army and Air Force use tactical tropospheric scatter systems developed by

Russian tropospheric relay communication network

Tropospheric Scatter Communications - the essentials

* {{Authority control Radio frequency propagation Atmospheric optical phenomena

Hay River Hay River may refer to:

Places

* Hay River, Northwest Territories

* Hay River, Wisconsin

Rivers

* Hay River (Wisconsin)

* Hay River (Canada), a river in Alberta and Northwest Territories, Canada

* Hay River, Northern Territory, Australia

* Hay R ...

- Port Radium - Lady Franklin Point

Lady Franklin Point is a landform in the Canadian Arctic territory of Nunavut. It is located on southwestern Victoria Island in the Coronation Gulf by Austin Bay at the eastern entrance of Dolphin and Union Strait.

The Point is uninhabited b ...

; -

:Guanabo

town in province is a beach town in the Ciudad de la Habana Province of Cuba. It is a ward (''consejo popular'') located within the municipality of Habana del Este halfway between the centre of Havana and Santa Cruz del Norte, at the mouth of the ...

to Florida City

Florida City is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. It is the southernmost municipality in the South Florida metropolitan area. Florida City is primarily a Miami suburb and a major agricultural area. As of the 2020 census, it h ...

;Project Offices - AT&T Corporation

AT&T Corporation, originally the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, is the subsidiary of AT&T Inc. that provides voice, video, data, and Internet telecommunications and professional services to businesses, consumers, and government agen ...

,

:

:Project Offices is the name sometimes used to refer to several structurally dependable facilities maintained by the ATT Corporation in the Mid-Atlantic states since the mid-th century to house an ongoing, non-public, company project. AT&T began constructing Project Offices in the . Since the inception of the Project Offices program, the company has chosen not to disclose the exact nature of business conducted at Project Offices. However, it has described them as ''central facilities''.

::* Pittsboro, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

::*Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

::*Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

::* Leesburg, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

::* Hagerstown, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

;Texas Towers - Air defence radars,

:The Texas Towers were a set of three radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

facilities off the eastern seaboard of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

which were used for surveillance by the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Si ...

during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. Modeled on the offshore oil drilling platforms first employed off the Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

coast, they were in operation from 1958 to 1963.

:

; Mid Canada Line,

:A series of five stations (070, 060, 050, 415, 410) in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

and Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

around the lower Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

. A series of six stations were built in Labrador and Quebec between Goose Bay and Sept-Îles between 1957–1958.

; Pinetree Line, Pole Vault

Pole vaulting, also known as pole jumping, is a track and field event in which an athlete uses a long and flexible pole, usually made from fiberglass or carbon fiber, as an aid to jump over a bar. Pole jumping competitions were known to the M ...

,

:Pole Vault

Pole vaulting, also known as pole jumping, is a track and field event in which an athlete uses a long and flexible pole, usually made from fiberglass or carbon fiber, as an aid to jump over a bar. Pole jumping competitions were known to the M ...

was series of fourteen stations providing communications for Eastern seaboard radar stations of the US/Canadian Pinetree line, running from N-31 Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay is an inlet of the Davis Strait in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the southeastern corner of Baffin Island. Its length is about and its width varies from about at its outlet into the Labrador Sea to ...

, Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

to N-22 St. John's, Newfoundland.

;White Alice

The White Alice Communications System (WACS, "White Alice" colloquially) was a United States Air Force telecommunication network with 80 radio stations constructed in Alaska during the Cold War. It used tropospheric scatter for over-the-horizon l ...

/DEW Line

The Distant Early Warning Line, also known as the DEW Line or Early Warning Line, was a system of radar stations in the northern Arctic region of Canada, with additional stations along the north coast and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (see Proj ...

/ DEW Training (Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

era), /

:A former military and civil communications network with eighty stations stretching up the western seaboard from Port Hardy, Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest by ...

north to Barter Island

Barter Island is an island located on the Arctic coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, east of Arey Island in the Beaufort Sea. It is about four miles (6 km) long and about two miles (3 km) wide at its widest point.

Until the late 19t ...

(BAR), west to Shemya, Alaska (SYA) in the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large v ...

(just a few hundred miles from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

) and east across arctic Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

to Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

. Note that not all station were troposcatter, but many were. It also included a training facility for White Alice/DEW line tropo-scatter network located between Pecatonica, Illinois to Streator, Illinois.

;DEW Line

The Distant Early Warning Line, also known as the DEW Line or Early Warning Line, was a system of radar stations in the northern Arctic region of Canada, with additional stations along the north coast and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (see Proj ...

(Post Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

era), /

:Several tropo-scatter networks providing communications for the extensive air-defence radar chain in the far north of Canada and the US.

; North Atlantic Radio System (NARS),

:NATO air-defence network stretching from RAF Fylingdales, via Mormond Hill, UK, Sornfelli

Sornfelli is a mountain plateau on the island of Streymoy in the Faroe Islands about 12 km from the capital Tórshavn (20 km by road). It is the site of a military station at 725m above sea level (asl). The Sornfelli Meteorological Stat ...

(Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

), Höfn, Iceland to Keflavik DYE-5, Rockville.

;European Tropospheric Scatter - Army (ET-A),

:A US Army network from RAF Fylingdales to a network in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and a single station in France (Maison Fort

Maison (French for "house") may refer to:

People

* Edna Maison (1892–1946), American silent-film actress

* Jérémy Maison (born 1993), French cyclist

* Leonard Maison, New York state senator 1834–1837

* Nicolas Joseph Maison (1771–1840), Ma ...

). The network became active on 1966.

;486L Mediterranean Communications System (MEDCOM),

: A network covering the Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an coast of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

from San Pablo, Spain in the west to Incirlik Air Base

Incirlik Air Base ( tr, İncirlik Hava Üssü) is a Turkish air base of slightly more than 3320 ac (1335 ha), located in the İncirlik quarter of the city of Adana, Turkey. The base is within an urban area of 1.7 million people, east of ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

in the East, with headquarters at Ringstead in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. Commissioned by the US Air Force in .

;Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

,

:Communications to British Forces Germany

British Forces Germany (''BFG'') was the generic name for the three services of the British Armed Forces, made up of service personnel, UK Civil Servants, and dependents (family members), based in Germany. It was established following the Secon ...

, running from Swingate

Swingate is a village near Dover in Kent, England. The population of the village is included in the civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which i ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

to Lammersdorf in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

.

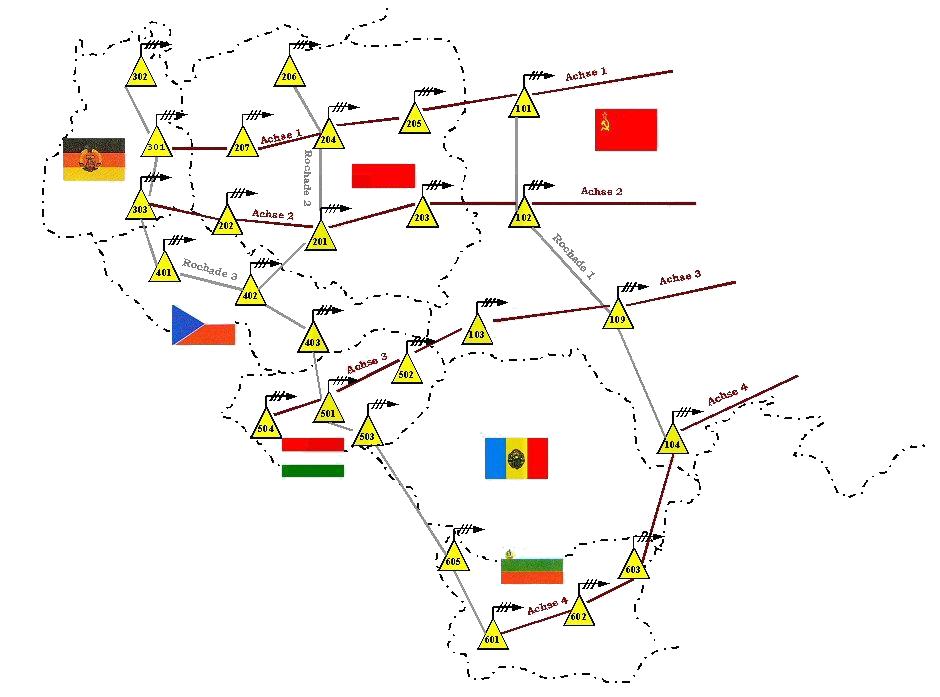

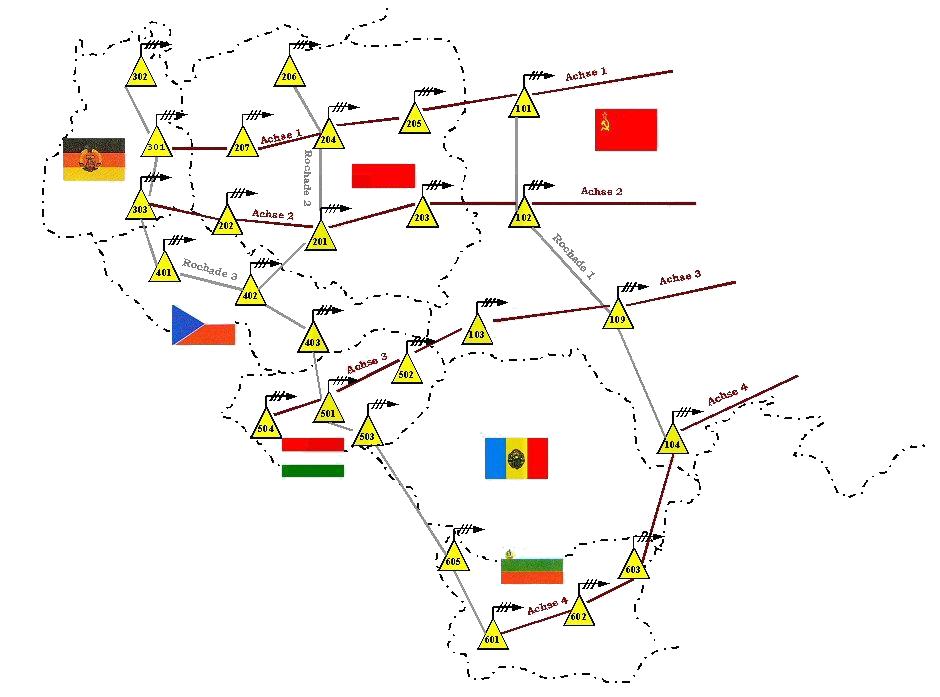

; Troposphären-Nachrichtensystem Bars, Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

:A Warsaw Pact tropo-scatter network stretching from near

:A Warsaw Pact tropo-scatter network stretching from near Rostok

Rostock (), officially the Hanseatic and University City of Rostock (german: link=no, Hanse- und Universitätsstadt Rostock), is the largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and lies in the Mecklenburgian part of the state, ...

in the DDR (Deutsches Demokratisches Republik), Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Byelorussia USSR, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

USSR and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

.

;TRRL SEVER,

:A Soviet network stretching across the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

.

; -  :A single section from

:A single section from Srinigar

Srinagar (English: , ) is the largest city and the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It lies in the Kashmir Valley on the banks of the Jhelum River, a tributary of the Indus, and Dal and Anchar lakes. The city is known for its natu ...

, Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, India to Dangara, Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

, USSR.

;Indian Air Force

The Indian Air Force (IAF) is the air force, air arm of the Indian Armed Forces. Its complement of personnel and aircraft assets ranks third amongst the air forces of the world. Its primary mission is to secure Indian airspace and to conduct ...

,

:Part of an Air Defence Network covering major air bases, radar installations and missile sites in Northern and central India. The network is being phased out to be replaced with more modern fiber-optic based communication systems.

;Peace Ruby, Spellout, Peace Net,

:An air-defence network set up by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

. ''Spellout'' built a radar and communications network in the north of Iran. ''PeaceRuby'' built another air-defence network in the south and ''PeaceNet'' integrated the two networks.

; -

:A tropo-scatter system linking Al Manamah

Manama ( ar, المنامة ', Bahrani pronunciation: ) is the capital and largest city of Bahrain, with an approximate population of 200,000 people as of 2020. Long an important trading center in the Persian Gulf, Manama is home to a very di ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

to Dubai

Dubai (, ; ar, wikt:دبي, دبي, translit=Dubayy, , ) is the List of cities in the United Arab Emirates#Major cities, most populous city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the capital of the Emirate of Dubai, the most populated of the 7 ...

, United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia (Middle East, The Middle East). It is ...

.

;Royal Air Force of Oman

The Royal Air Force of Oman ( ar, سلاح الجو السلطاني عمان, Silāḥ al-Jaww as-Sulṭāniy ‘Umān or RAFO) is the air arm of the Armed Forces of Oman.

History Sultan of Oman's Air Force era

The Sultan of Oman's Air Force ...

,

:A tropo-scatter communications system providing military comms to the former SOAF - Sultan of Oman's Air Force, (now RAFO - Royal Air Force of Oman), across the Sultanate of Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

.

;Royal Saudi Air Force

The Royal Saudi Air Force ( ar, الْقُوَّاتُ الْجَوِّيَّةُ الْمَلَكِيَّةْ ٱلسُّعُوْدِيَّة, Al-Quwwat Al-Jawiyah Al-Malakiyah as-Su’udiyah) (RSAF) is the aviation branch of the Saudi Arabia ...

,

:A Royal Saudi Air Force tropo-scatter network linking major airbases and population centres in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the Ara ...

.

;Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

,

:A single system linking Sana'a

Sanaa ( ar, صَنْعَاء, ' , Yemeni Arabic: ; Old South Arabian: 𐩮𐩬𐩲𐩥 ''Ṣnʿw''), also spelled Sana'a or Sana, is the capital and largest city in Yemen and the centre of Sanaa Governorate. The city is not part of the Gover ...

with Sa'dah.

;BACK PORCH and Integrated Wideband Communications System (IWCS),

:Two networks run by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

linking military bases in Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

and South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

. Stations were located at Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estimated populati ...

, Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Pleiku, Nha Trang, Vung Chua mountain () Quy Nhon

Quy Nhon ( vi, Quy Nhơn ) is a coastal city in Bình Định province in central Vietnam. It is composed of 16 wards and five communes with a total of . Quy Nhon is the capital of Bình Định province. As of 2019 its population was 457,400. H ...

, Monkey Mountain Facility Da Nang

Nang or DanangSee also Danang Dragons ( ; vi, Đà Nẵng, ) is a class-1 municipality and the fifth-largest city in Vietnam by municipal population. It lies on the coast of the East Sea of Vietnam at the mouth of the Hàn River, and is on ...

, Phu Bai Combat Base

Phu Bai Combat Base (also known as Phu Bai Airfield and Camp Hochmuth) is a former U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps base south of Huế, in central Vietnam.

History

1962-5

The Army Security Agency, operating under cover of the 3rd Radio Rese ...

, Pr Line () near Da Lat

Da Lat (also written as Dalat, vi, Đà Lạt; ), is the capital of Lâm Đồng Province and the largest city of the Central Highlands region in Vietnam. The city is located above sea level on the Langbian Plateau. Da Lat is one of the mo ...

, Hon Cong mountain An Khê

An Khê is a town (''thị xã'') of Gia Lai province in the Central Highlands region of Vietnam.

As of 2003 the district had a population of 63,118. The district covers an area of 199 km². The district capital lies at An Khê.

Locat ...

, Phu Lam () Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

, VC Hill () Vũng Tàu

Vũng Tàu (''Hanoi accent:'' , ''Saigon accent:'' ) is the largest city of Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu province in southern Vietnam. The city area is , consists of 13 urban wards and one commune of Long Sơn Islet. Vũng Tàu was the capital of the p ...

and Cần Thơ

Cần Thơ, also written as Can Tho or Cantho (: , : ), is the fourth-largest city in Vietnam, and the largest city along the Mekong Delta region in Vietnam.

It is noted for its floating markets, rice paper-making village, and picturesque r ...

.

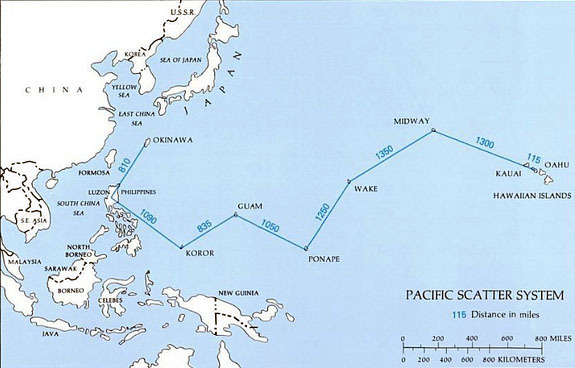

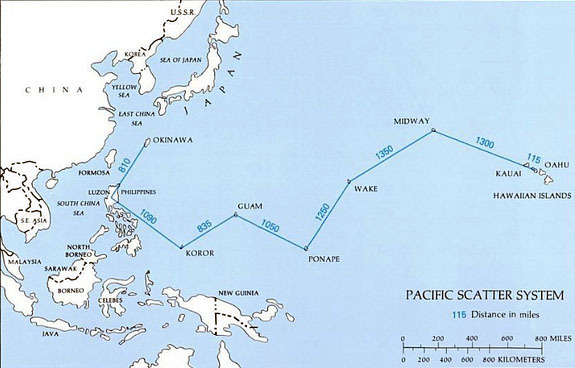

;Phil-Tai-Oki,

:A system linking the Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

with the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Okinawa

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 Square kilometre, km2 (880 sq mi).

...

.

; Cable & Wireless Caribbean network

:A troposcatter link was established by Cable & Wireless in 1960, linking Barbados with Port of Spain, Trinidad. The network was extended further south to Georgetown, Guyana in 1965.

;Japanese Troposcatter Networks,

:Two networks linking Japanese islands from North to South.

Tactical Troposcatter Communication systems

As well as the permanent networks detailed above, there have been many tactical transportable systems produced by several countries: ;Soviet / Russian Troposcatter Systems : MNIRTI R-423-1 Brig-1/R-423-2A Brig-2A/R-423-1KF : MNIRTI R-444 Eshelon / R-444-7,5 Eshelon D : MNIRTI R-420 Atlet-D : NIRTI R-417 Baget/R-417S Baget S :NPP Radiosvyaz R-412

NPP may refer to:

Politics

* National People's Power, Sri Lanka

*National Patriotic Party, Liberia

* National People's Party (The Gambia)

* National People's Party (India), a political party in India founded by PA Sangma

*National Peoples Party ...

A/B/F/S TORF

: MNIRTI R-410/R-410-5,5/R-410-7,5 Atlet / Albatros

: MNIRTI R-408/R-408M Baklan

;People's Republic of China (PRoC), People's Liberation Army (PLA) Troposcatter Systems

:CETC TS-504 {{Disambig

* China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, a state-owned company established in 2002 by People's Republic of China

* ''Chambres extraordinaires au sein des tribunaux cambodgiens'', commonly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, est ...

Troposcatter Communication System

: CETC TS-510/GS-510 Troposcatter Communication System

;Western Troposcatter Systems

: AN/TRC-97 Troposcatter Communication System

: AN/TRC-170 Tropospheric Scatter Microwave Radio Terminal

: AN/GRC-201 Troposcatter Communication System

The U.S. Army and Air Force use tactical tropospheric scatter systems developed by

The U.S. Army and Air Force use tactical tropospheric scatter systems developed by Raytheon

Raytheon Technologies Corporation is an American multinational aerospace and defense conglomerate headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. It is one of the largest aerospace and defense manufacturers in the world by revenue and market capitali ...

for long haul communications. The systems come in two configurations, the original "heavy tropo", and a newer "light tropo" configuration exist. The systems provide four multiplexed group channels and trunk encryption, and 16 or 32 local analog phone extensions. The U.S. Marine Corps also uses the same device, albeit an older version.

See also

*Radio propagation

Radio propagation is the behavior of radio waves as they travel, or are propagated, from one point to another in vacuum, or into various parts of the atmosphere.

As a form of electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, radio waves are affect ...

* Non-line-of-sight propagation

* Microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

* ACE High

Allied Command Europe Highband, better known as ACE High, was a fixed service NATO radiocommunication and early warning system dating back to 1956. After extensive testing ACE High was accepted by NATO to become operational in 1964/1965.

The fr ...

- Cold war era NATO European troposcatter network

* White Alice Communications System

The White Alice Communications System (WACS, "White Alice" colloquially) was a United States Air Force telecommunication network with 80 radio stations constructed in Alaska during the Cold War. It used tropospheric scatter for over-the-horizon l ...

- Cold war era Alaskan tropospheric communications link

* List of White Alice Communications System sites

This is a list of White Alice Communications System sites. The White Alice Communications System (WACS) was a United States Air Force telecommunication link system constructed in Alaska during the Cold War. It featured tropospheric scatter links ...

* TV-FM DX

* Distant Early Warning Line

The Distant Early Warning Line, also known as the DEW Line or Early Warning Line, was a system of radar stations in the northern Arctic region of Canada, with additional stations along the north coast and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (see Proj ...

References

Citations

Bibliography

*External links

Russian tropospheric relay communication network

Tropospheric Scatter Communications - the essentials

* {{Authority control Radio frequency propagation Atmospheric optical phenomena