"Too big to fail" (TBTF) is a

theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

in

banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

and

finance

Finance refers to monetary resources and to the study and Academic discipline, discipline of money, currency, assets and Liability (financial accounting), liabilities. As a subject of study, is a field of Business administration, Business Admin ...

that asserts that certain

corporation

A corporation or body corporate is an individual or a group of people, such as an association or company, that has been authorized by the State (polity), state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law as ...

s, particularly

financial institution

A financial institution, sometimes called a banking institution, is a business entity that provides service as an intermediary for different types of financial monetary transactions. Broadly speaking, there are three major types of financial ins ...

s, are so large and so interconnected with an economy that their failure would be disastrous to the greater

economic system

An economic system, or economic order, is a system of production, resource allocation and distribution of goods and services within an economy. It includes the combination of the various institutions, agencies, entities, decision-making proces ...

, and therefore should be

supported by government when they face potential failure. The colloquial term "too big to fail" was popularized by

U.S. Congressman

Stewart McKinney in a 1984 Congressional hearing, discussing the

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's intervention with

Continental Illinois

The Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company was an American bank established in 1910, which was at its peak the seventh-largest commercial bank in the United States as measured by deposits, with approximately $40 billion in assets. ...

. The term had previously been used occasionally in the press, and similar thinking had motivated earlier bank bailouts.

The term emerged as prominent in public discourse following the

2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

. Critics see the policy as counterproductive and that large banks or other institutions should be left to fail if their

risk management

Risk management is the identification, evaluation, and prioritization of risks, followed by the minimization, monitoring, and control of the impact or probability of those risks occurring. Risks can come from various sources (i.e, Threat (sec ...

is not effective. Some critics, such as economist

Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He worked as a private adviser and provided consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates L ...

, believe that such large organizations should be deliberately broken up: "If they're too big to fail, they're too big."

Some economists such as

Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman ( ; born February 28, 1953) is an American New Keynesian economics, New Keynesian economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the CUNY Graduate Center, Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He ...

hold that

financial crises

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with Bank run#Systemic banki ...

arise principally from banks being under-regulated rather than their size, using the widespread collapse of small banks in the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

to illustrate this argument.

[Paul Krugma]

"Financial Reform 101"

April 1, 2010[Paul Krugma]

"Stop 'Stop Too Big To Fail'."

''New York Times'', April 21, 2010[Paul Krugma]

"Too big to fail FAIL"

''New York Times'', June 18, 2009[Paul Krugma]

"A bit more on too big to fail and related"

''New York Times'', June 19, 2009

In 2014, the

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

and others said the problem still had not been dealt with.

While the individual components of the new regulation for systemically important banks (additional

capital requirement

A capital requirement (also known as regulatory capital, capital adequacy or capital base) is the amount of capital a bank or other financial institution has to have as required by its financial regulator. This is usually expressed as a capital ...

s, enhanced supervision and resolution regimes) likely reduced the prevalence of TBTF, the fact that there is a definite

list of systemically important banks considered TBTF has a partly offsetting impact.

Definition

Federal Reserve Chair

Ben Bernanke

Ben Shalom Bernanke ( ; born December 13, 1953) is an American economist who served as the 14th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014. After leaving the Federal Reserve, he was appointed a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Insti ...

also defined the term in 2010: "A too-big-to-fail firm is one whose size, complexity, interconnectedness, and critical functions are such that, should the firm go unexpectedly into liquidation, the rest of the financial system and the economy would face severe adverse consequences." He continued that: "Governments provide support to too-big-to-fail firms in a crisis not out of favoritism or particular concern for the management, owners, or creditors of the firm, but because they recognize that the consequences for the broader economy of allowing a disorderly failure greatly outweigh the costs of avoiding the failure in some way. Common means of avoiding failure include facilitating a merger, providing credit, or injecting government capital, all of which protect at least some creditors who otherwise would have suffered losses. ... If the has a single lesson, it is that the too-big-to-fail problem must be solved."

Bernanke cited several risks with too-big-to-fail institutions:

# These firms generate severe

moral hazard

In economics, a moral hazard is a situation where an economic actor has an incentive to increase its exposure to risk because it does not bear the full costs associated with that risk, should things go wrong. For example, when a corporation i ...

: "If creditors believe that an institution will not be allowed to fail, they will not demand as much compensation for risks as they otherwise would, thus weakening market discipline; nor will they invest as many resources in monitoring the firm's risk-taking. As a result, too-big-to-fail firms will tend to take more risk than desirable, in the expectation that they will receive assistance if their bets go bad."

# It creates an uneven playing field between big and small firms. "This unfair competition, together with the incentive to grow that too-big-to-fail provides, increases risk and artificially raises the market share of too-big-to-fail firms, to the detriment of economic efficiency as well as financial stability."

# The firms themselves become major risks to overall financial stability, particularly in the absence of adequate resolution tools. Bernanke wrote: "The failure of

Lehman Brothers

Lehman Brothers Inc. ( ) was an American global financial services firm founded in 1850. Before filing for bankruptcy in 2008, Lehman was the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States (behind Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Merril ...

and the near-failure of several other large, complex firms significantly worsened the crisis and the recession by disrupting financial markets, impeding credit flows, inducing sharp declines in asset prices, and hurting confidence. The failures of smaller, less interconnected firms, though certainly of significant concern, have not had substantial effects on the stability of the financial system as a whole."

Background on banking regulation

Depository banks

Prior to the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, U.S. consumer bank deposits were not guaranteed by the government, increasing the risk of a

bank run

A bank run or run on the bank occurs when many Client (business), clients withdraw their money from a bank, because they believe Bank failure, the bank may fail in the near future. In other words, it is when, in a fractional-reserve banking sys ...

, in which a large number of depositors withdraw their deposits at the same time. Since banks lend most of the deposits and only keep a fraction actually on hand, a bank run can render the bank insolvent. During the Depression, hundreds of banks became insolvent and depositors lost their money. As a result, the U.S. enacted the

1933 Banking Act

The Banking Act of 1933 () was a statute enacted by the United States Congress that established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and imposed various other banking reforms. The entire law is often referred to as the Glass–Stea ...

, sometimes called the

Glass–Steagall Act, which created the

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to insure deposits up to a limit of $2,500, with successive increases to the current $250,000. In exchange for the deposit insurance provided by the federal government, depository banks are highly regulated and expected to invest excess customer deposits in lower-risk assets.

After the Great Depression, it has become a problem for financial companies that they are too big to fail, because there is a close connection between financial institutions involved in financial market transactions. It brings liquidity in the markets of various financial instruments. The crisis in 2008 originated when the liquidity and value of financial instruments held and issued by banks and financial institutions decreased sharply.

Investment banks and the shadow banking system

In contrast to depository banks, investment banks generally obtain funds from sophisticated investors and often make complex, risky investments with the funds, speculating either for their own account or on behalf of their investors. They also are "market makers" in that they serve as intermediaries between two investors that wish to take opposite sides of a financial transaction. The Glass–Steagall Act separated investment and depository banking until its repeal in 1999. Prior to 2008, the government did not explicitly guarantee the investor funds, so investment banks were not subject to the same regulations as depository banks and were allowed to take considerably more risk.

Investment banks, along with other innovations in banking and finance referred to as the

shadow banking system

The shadow banking system is a term for the collection of non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) that legally provide services similar to traditional commercial banks but outside normal banking regulations. S&P Global estimates that, at end-2 ...

, grew to rival the depository system by 2007. They became subject to the equivalent of a bank run in 2007 and 2008, in which investors (rather than depositors) withdrew sources of financing from the shadow system. This run became known as the

subprime mortgage crisis

The American subprime mortgage crisis was a multinational financial crisis that occurred between 2007 and 2010, contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. It led to a severe economic recession, with millions becoming unemployed and many busines ...

. During 2008, the five largest U.S. investment banks either failed (Lehman Brothers), were bought out by other banks at fire-sale prices (Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch) or were at risk of failure and obtained depository banking charters to obtain additional Federal Reserve support (Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley). In addition, the government provided bailout funds via the

Troubled Asset Relief Program

The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) is a program of the United States government to purchase toxic assets and equity from financial institutions to strengthen its financial sector that was passed by Congress and signed into law by U.S. Presi ...

in 2008.

Fed Chair

Ben Bernanke

Ben Shalom Bernanke ( ; born December 13, 1953) is an American economist who served as the 14th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014. After leaving the Federal Reserve, he was appointed a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Insti ...

described in November 2013 how the

Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic or Knickerbocker Crisis, was a financial crisis that took place in the United States over a three-week period starting in mid-October, when the New York Stock Exchange suddenly fell almost ...

was essentially a run on the non-depository financial system, with many parallels to the crisis of 2008. One of the results of the Panic of 1907 was the creation of the

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

in 1913.

Resolution authority

Before 1950, U.S. federal bank regulators had essentially two options for resolving an

insolvent

In accounting, insolvency is the state of being unable to pay the debts, by a person or company ( debtor), at maturity; those in a state of insolvency are said to be ''insolvent''. There are two forms: cash-flow insolvency and balance-sheet in ...

institution: 1) closure, with

liquidation

Liquidation is the process in accounting by which a Company (law), company is brought to an end. The assets and property of the business are redistributed. When a firm has been liquidated, it is sometimes referred to as :wikt:wind up#Noun, w ...

of assets and payouts for

insured depositors; or 2) purchase and assumption, encouraging the acquisition of assets and assumption of

liabilities by another firm. A third option was made available by the

Federal Deposit Insurance Act of 1950: providing assistance, the power to support an institution through loans or direct federal acquisition of assets, until it could recover from its distress.

The statute limited the "assistance" option to cases where "continued operation of the bank is essential to provide adequate banking service". Regulators shunned this third option for many years, fearing that if regionally or nationally important banks were thought generally immune to liquidation, markets in their shares would be distorted. Thus, the assistance option was never employed during the period 1950–1969, and very seldom thereafter.

Research into historical banking trends suggests that the consumption loss associated with National Banking Era bank runs was far more costly than the consumption loss from stock market crashes.

The

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act was passed in 1991, giving the FDIC the responsibility to rescue an insolvent bank by the least costly method. The Act had the implicit goal of eliminating the widespread belief among depositors that a loss of depositors and bondholders will be prevented for large banks. However, the Act included an exception in cases of systemic risk, subject to the approval of two-thirds of the FDIC board of directors, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, and the Treasury Secretary.

Analysis

Bank size and concentration

Bank size, complexity, and interconnectedness with other banks may inhibit the ability of the government to resolve (wind-down) the bank without significant disruption to the financial system or economy, as occurred with the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008. This risk of "too big to fail" entities increases the likelihood of a government bailout using taxpayer dollars.

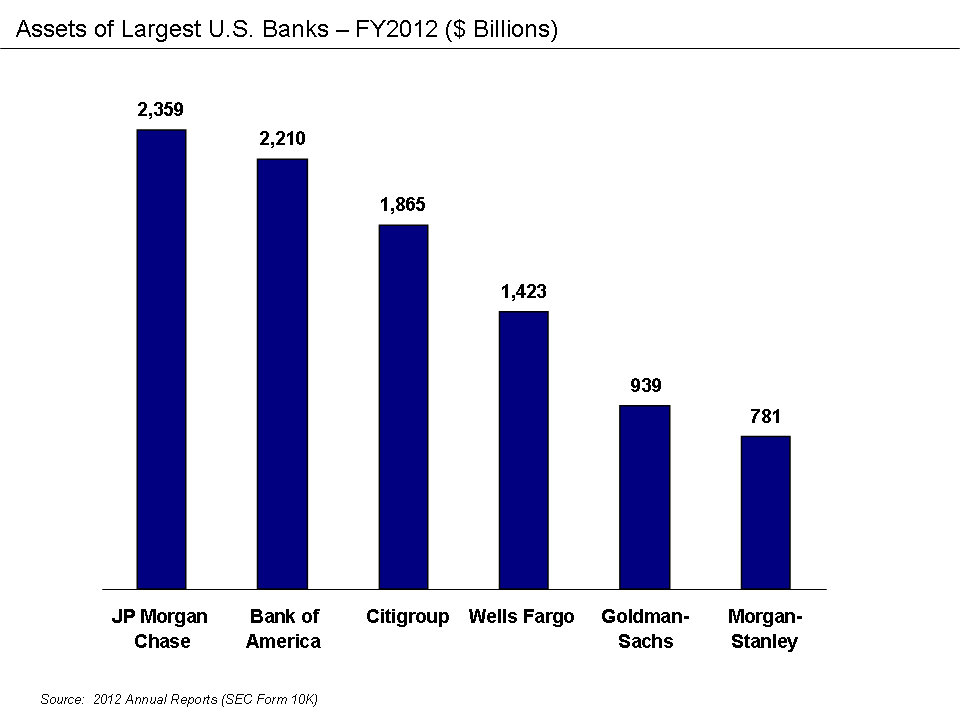

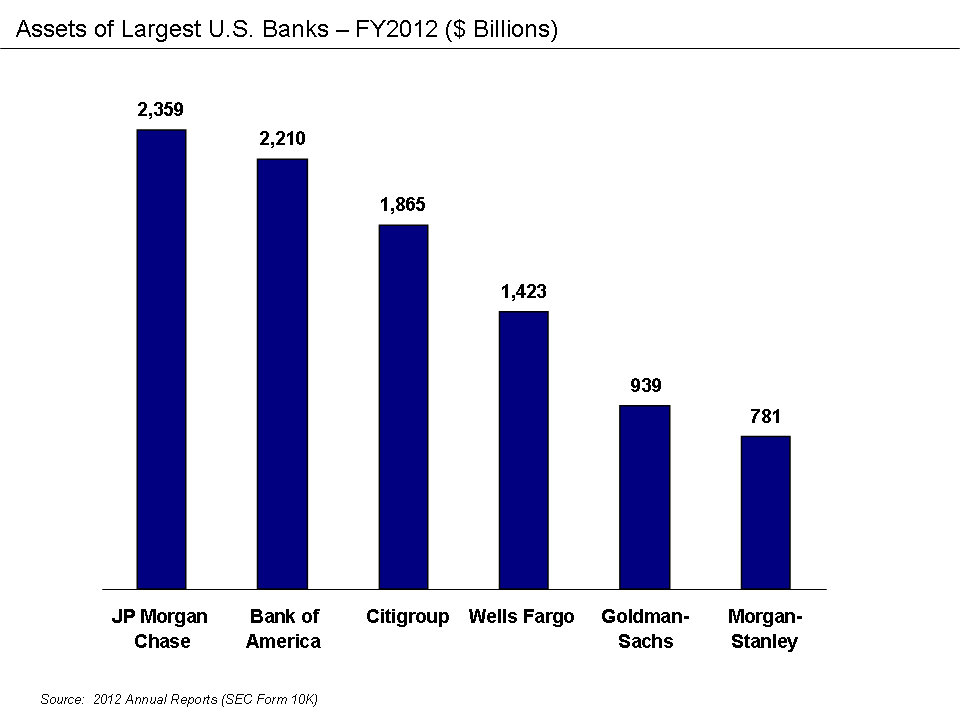

The largest U.S. banks continue to grow larger while the concentration of bank assets increases. The largest six U.S. banks had assets of $9,576 billion as of year-end 2012, per their 2012 annual reports (SEC Form 10K). The top 5 U.S. banks had approximately 30% of the U.S. banking assets in 1998; this rose to 45% by 2008 and to 48% by 2010, before falling to 47% in 2011.

This concentration continued despite the

subprime mortgage crisis

The American subprime mortgage crisis was a multinational financial crisis that occurred between 2007 and 2010, contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. It led to a severe economic recession, with millions becoming unemployed and many busines ...

and its aftermath. During March 2008, JP Morgan Chase acquired investment bank Bear Stearns. Bank of America acquired investment bank Merrill Lynch in September 2008. Wells Fargo acquired Wachovia in January 2009. Investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley obtained depository bank holding company charters, which gave them access to additional Federal Reserve credit lines.

Bank deposits for all U.S. banks ranged between approximately 60–70% of GDP from 1960 to 2006, then jumped during the crisis to a peak of nearly 84% in 2009 before falling to 77% by 2011.

The number of U.S. commercial and savings bank institutions reached a peak of 14,495 in 1984; this fell to 6,532 by the end of 2010. The ten largest U.S. banks held nearly 50% of U.S. deposits as of 2011.

Implicit guarantee subsidy

Since the full amount of the deposits and debts of "too big to fail" banks are effectively guaranteed by the government, large depositors and investors view investments with these banks as a safer investment than deposits with smaller banks. Therefore, large banks are able to pay lower interest rates to depositors and investors than small banks are obliged to pay.

In October 2009,

Sheila Bair

Sheila Colleen Bair (born April 3, 1954) is an American former government official who was the 19th Chair of the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) from 2006 to 2011, during which time she shortly after taking charge of the FDIC i ...

, at that time the Chairperson of the FDIC, commented:

A study conducted by the

Center for Economic and Policy Research

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) is an American think tank that specializes in economic policy. Based in Washington, D.C. CEPR was co-founded by economists Dean Baker and Mark Weisbrot in 1999.

Considered a left-leaning orga ...

found that the difference between the

cost of funds for banks with more than $100 billion in assets and the cost of funds for smaller banks widened dramatically after the formalization of the "too big to fail" policy in the U.S. in the fourth quarter of 2008. This shift in the large banks' cost of funds was in effect equivalent to an indirect "too big to fail" subsidy of $34 billion per year to the 18 U.S. banks with more than $100 billion in assets.

The editors of Bloomberg View estimated there was an $83 billion annual subsidy to the 10 largest United States banks, reflecting a funding advantage of 0.8 percentage points due to implicit government support, meaning the profits of such banks are largely a taxpayer-backed illusion.

Another study by Frederic Schweikhard and Zoe Tsesmelidakis estimated the amount saved by America's biggest banks from having a perceived safety net of a government bailout was $120 billion from 2007 to 2010.

[Brendan Greeley]

"The Price of Too Big to Fail"

''BusinessWeek'', July 5, 2012 For America's biggest banks the estimated savings was $53 billion for

Citigroup

Citigroup Inc. or Citi (Style (visual arts), stylized as citi) is an American multinational investment banking, investment bank and financial services company based in New York City. The company was formed in 1998 by the merger of Citicorp, t ...

, $32 billion for

Bank of America

The Bank of America Corporation (Bank of America) (often abbreviated BofA or BoA) is an American multinational investment banking, investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered at the Bank of America Corporate Center in ...

, $10 billion for

JPMorgan

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (stylized as JPMorganChase) is an American multinational finance corporation headquartered in New York City and incorporated in Delaware. It is the largest bank in the United States, and the world's largest bank by mar ...

, $8 billion for

Wells Fargo

Wells Fargo & Company is an American multinational financial services company with a significant global presence. The company operates in 35 countries and serves over 70 million customers worldwide. It is a systemically important fi ...

, and $4 billion for

AIG

American International Group, Inc. (AIG) is an American multinational finance and insurance corporation with operations in more than 80 countries and jurisdictions. As of 2023, AIG employed 25,200 people. The company operates through three core ...

. The study noted that passage of the

Dodd–Frank Act—which promised an end to bailouts—did nothing to raise the

price of credit (i.e., lower the implicit subsidy) for the "too-big-to-fail" institutions.

One 2013 study (Acharya, Anginer, and Warburton) measured the funding cost advantage provided by implicit government support to large financial institutions. Credit spreads were lower by approximately 28 basis points (0.28%) on average over the 1990–2010 period, with a peak of more than 120 basis points in 2009. In 2010, the implicit subsidy was worth nearly $100 billion to the largest banks. The authors concluded: "Passage of Dodd–Frank did not eliminate expectations of government support."

Economist

Randall S. Kroszner summarized several approaches to evaluating the funding cost differential between large and small banks. The paper discusses methodology and does not specifically answer the question of whether larger institutions have an advantage.

During November 2013, the Moody's credit rating agency reported that it would no longer assume the eight largest U.S. banks would receive government support in the event they faced bankruptcy. However, the GAO reported that politicians and regulators would still face significant pressure to bail out large banks and their creditors in the event of a financial crisis.

Moral hazard

Some critics have argued that "The way things are now banks reap profits if their trades pan out, but taxpayers can be stuck picking up the tab if their big bets sink the company." Additionally, as discussed by Senator

Bernie Sanders

Bernard Sanders (born September8, 1941) is an American politician and activist who is the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from the state of Vermont. He is the longest-serving independ ...

, if taxpayers are contributing to rescue these companies from bankruptcy, they "should be rewarded for assuming the risk by sharing in the gains that result from this government bailout".

In this sense,

Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He worked as a private adviser and provided consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates L ...

affirms that, "Failure is an integral part, a necessary part of a market system." Thereby, although the financial institutions that were bailed out were indeed important to the financial system, the fact that they took risk beyond what they would otherwise, should be enough for the Government to let them face the consequences of their actions. It would have been a lesson to motivate institutions to proceed differently next time.

Inability to prosecute

The political power of large banks and risks of economic impact from major prosecutions has led to use of the term "too big to jail" regarding the leaders of large financial institutions.

On March 6, 2013, then

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the Federal government of the United States, federal government. The attorney general acts as the princi ...

Eric Holder testified to the

Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

that the size of large financial institutions has made it difficult for the

Justice Department to bring criminal charges when they are suspected of crimes, because such charges can threaten the existence of a bank and therefore their interconnectedness may endanger the national or global economy. "Some of these institutions have become too large," Holder told the Committee. "It has an inhibiting impact on our ability to bring resolutions that I think would be more appropriate." In this he contradicted earlier written testimony from a deputy assistant attorney general, who defended the Justice Department's "vigorous enforcement against wrongdoing".

Holder has financial ties to at least one law firm benefiting from ''de facto'' immunity to prosecution, and prosecution rates against crimes by large financial institutions are at 20-year lows.

Four days later,

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas President

Richard W. Fisher and Vice-President Harvey Rosenblum co-authored a ''Wall Street Journal'' op-ed about the failure of the

Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, commonly referred to as Dodd–Frank, is a United States federal law that was enacted on July 21, 2010. The law overhauled financial regulation in the aftermath of the Great Reces ...

to provide for adequate regulation of large financial institutions. In advance of his March 8 speech to the

Conservative Political Action Conference

The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC ) is an annual political conference attended by Conservatism in the United States, conservative Activism, activists and officials from across the United States. CPAC is hosted by the American ...

, Fisher proposed requiring

breaking up large banks into smaller banks so that they are "too small to save", advocating the withholding from mega-banks access to both

Federal Deposit Insurance and

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

discount window

Discount may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Discount (band), punk rock band that formed in Vero Beach, Florida in 1995 and disbanded in 2000

* ''Discount'' (film), French comedy-drama film

* "Discounts" (song), 2020 single by American rapper C ...

, and requiring disclosure of this lack of federal insurance and

financial solvency support to their customers. This was the first time such a proposal had been made by a high-ranking U.S. banking official or a prominent conservative.

Other conservatives including

Thomas Hoenig,

Ed Prescott,

Glenn Hubbard, and

David Vitter also advocated breaking up the largest banks,

but liberal commentator

Matthew Yglesias

Matthew Yglesias (; born May 18, 1981) is an American blogger and journalist who writes about economics and politics. Yglesias has written columns and articles for publications such as ''The American Prospect'', ''The Atlantic'', and ''Slate''. I ...

questioned their motives and the existence of a true bipartisan consensus.

In a January 29, 2013, letter to Holder, Senators

Sherrod Brown

Sherrod Campbell Brown ( ; born November 9, 1952) is an American politician who served from 2007 to 2025 as a United States senator from Ohio. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the U.S. representative for from 1993 to 2007 and the 47t ...

(

D-

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

) and

Charles Grassley (

R-

Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

) had criticized this Justice Department policy citing "important questions about the Justice Department's prosecutorial philosophy". After receipt of a

DoJ response letter, Brown and Grassley issued a statement saying, "The Justice Department's response is aggressively evasive. It does not answer our questions. We want to know how and why the Justice Department has determined that certain financial institutions are 'too big to jail' and that prosecuting those institutions would damage the financial system."

Kareem Serageldin pleaded guilty on November 22, 2013, for his role in inflating the value of mortgage bonds as the housing market collapsed, and was sentenced to two and a half years in prison.

As of April 30, 2014, Serageldin remains the only

Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

executive prosecuted as a result of the

2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

. The much smaller

Abacus Federal Savings Bank was prosecuted (but exonerated after a jury trial) for selling fraudulent mortgages to

Fannie Mae

The Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), commonly known as Fannie Mae, is a United States government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) and, since 1968, a publicly traded company. Founded in 1938 during the Great Depression as part of the New ...

.

Solutions

The proposed solutions to the "too big to fail" issue are controversial. Some options include breaking up the banks, introducing regulations to reduce risk, adding higher bank taxes for larger institutions, and increasing monitoring through oversight committees.

Breaking up the largest banks

More than fifty economists, financial experts, bankers, finance industry groups, and banks themselves have called for breaking up large banks into smaller institutions.

This is advocated both to limit risk to the financial system posed by the largest banks as well as to limit their political influence.

For example, economist

Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz (; born February 9, 1943) is an American New Keynesian economist, a public policy analyst, political activist, and a professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2 ...

wrote in 2009 that: "In the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere, large banks have been responsible for the bulk of the

ailoutcost to taxpayers. America has let 106 smaller banks go bankrupt this year alone. It's the mega-banks that present the mega-costs ... banks that are too big to fail are too big to exist. If they continue to exist, they must exist in what is sometimes called a 'utility' model, meaning that they are heavily regulated." He also wrote about several causes of the

subprime mortgage crisis

The American subprime mortgage crisis was a multinational financial crisis that occurred between 2007 and 2010, contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. It led to a severe economic recession, with millions becoming unemployed and many busines ...

related to the size, incentives, and interconnection of the mega-banks.

Reducing risk-taking through regulation

The United States passed the Dodd–Frank Act in July 2010 to help strengthen regulation of the financial system in the wake of the

subprime mortgage crisis

The American subprime mortgage crisis was a multinational financial crisis that occurred between 2007 and 2010, contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. It led to a severe economic recession, with millions becoming unemployed and many busines ...

that began in 2007. Dodd–Frank requires banks to reduce their risk taking, by requiring greater financial cushions (i.e., lower leverage ratios or higher capital ratios), among other steps.

Banks are required to maintain a ratio of high-quality, easily sold assets, in the event of financial difficulty either at the bank or in the financial system. These are liquidity requirements.

Since the 2008 crisis, regulators have worked with banks to reduce leverage ratios. For example, the leverage ratio for investment bank Goldman Sachs declined from a peak of 25.2 during 2007 to 11.4 in 2012, indicating a much-reduced risk profile.

The Dodd–Frank Act includes a form of the

Volcker Rule

The Volcker Rule is sectioof the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (). The rule was originally proposed by American economist and former United States Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker in 2010 to restrict United S ...

, a proposal to ban proprietary trading by commercial banks. Proprietary trading refers to using customer deposits to speculate in risky assets for the benefit of the bank rather than customers. The Dodd–Frank Act as enacted into law includes several loopholes to the ban, allowing proprietary trading in certain circumstances. However, the regulations required to enforce these elements of the law were not implemented during 2013 and were under attack by bank lobbying efforts.

Another major banking regulation, the

Glass–Steagall Act from 1933, was effectively repealed in 1999. The repeal allowed depository banks to enter into additional lines of business. Senators John McCain and Elizabeth Warren proposed bringing back Glass–Steagall during 2013.

Too big to fail tax

Economist

Willem Buiter proposes a tax to internalize the massive costs inflicted by "too big to fail" institution. "When size creates externalities, do what you would do with any negative externality: tax it. The other way to limit size is to tax size. This can be done through capital requirements that are progressive in the size of the business (as measured by value added, the size of the balance sheet or some other metric). Such measures for preventing the New Darwinism of the survival of the fittest and the politically best connected should be distinguished from regulatory interventions based on the narrow leverage ratio aimed at regulating risk (regardless of size, except for a de minimis lower limit)."

Monitoring

A policy research and development entity, the

Financial Stability Board

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system. It was established in the 2009 G20 Pittsburgh Summit as a successor to the Financial Stability Forum (FSF) ...

, releases an annual list of banks worldwide that are considered "systemically important financial institutions"—financial organizations whose size ''and role'' mean that any failure could cause serious systemic problems. As of 2022, these are:

*

JPMorgan Chase

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (stylized as JPMorganChase) is an American multinational financial services, finance corporation headquartered in New York City and incorporated in Delaware. It is List of largest banks in the United States, the largest ba ...

*

Bank of America

The Bank of America Corporation (Bank of America) (often abbreviated BofA or BoA) is an American multinational investment banking, investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered at the Bank of America Corporate Center in ...

*

Citigroup

Citigroup Inc. or Citi (Style (visual arts), stylized as citi) is an American multinational investment banking, investment bank and financial services company based in New York City. The company was formed in 1998 by the merger of Citicorp, t ...

*

HSBC Holdings plc

*

Bank of China

The Bank of China (BOC; ; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Banco da China'') is a state-owned Chinese Multinational corporation, multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Beijing, Beijing, China. It is one of ...

*

Barclays

Barclays PLC (, occasionally ) is a British multinational universal bank, headquartered in London, England. Barclays operates as two divisions, Barclays UK and Barclays International, supported by a service company, Barclays Execution Services ...

*

BNP Paribas

BNP Paribas (; sometimes referred to as BNPP or BNP) is a French multinational universal bank and financial services holding company headquartered in Paris. It was founded in 2000 from the merger of two of France's foremost financial instituti ...

*

Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank AG (, ) is a Germany, German multinational Investment banking, investment bank and financial services company headquartered in Frankfurt, Germany, and dual-listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange.

...

*

Goldman Sachs

The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. ( ) is an American multinational investment bank and financial services company. Founded in 1869, Goldman Sachs is headquartered in Lower Manhattan in New York City, with regional headquarters in many internationa ...

*

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC; zh, 中国工商银行) is a Chinese partially state-owned multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Beijing, China. It is the largest of the " big four" banks ...

*

Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group

is a Japanese bank holding and financial services company headquartered in Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. MUFG was created in 2005 by merger between and UFJ Holdings (株式会社UFJホールディングス; ''kabushikigaisha yūefujei hōrudingusu'' ...

*

Agricultural Bank of China

The Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), also known as AgBank, is a Chinese partially state-owned multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Beijing, China. It is one of the " big four" banks in China, and the second ...

*

BNY Mellon

The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation, commonly known as BNY, is an American international financial services company headquartered in New York City. It was established in its current form in July 2007 by the merger of the Bank of New York an ...

*

China Construction Bank

The China Construction Bank Corporation (CCB) is a Chinese partially state-owned Multinational corporation, multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Beijing, Beijing, China. It is one of the "Big four banks, big ...

*

Credit Suisse

Credit Suisse Group AG (, ) was a global Investment banking, investment bank and financial services firm founded and based in Switzerland. According to UBS, eventually Credit Suisse was to be fully integrated into UBS. While the integration ...

*

*

Groupe BPCE

*

Crédit Agricole

Crédit Agricole Group (), sometimes called La banque verte (, , due to its historical ties to farming), is a French international banking group and the world's largest cooperative financial institution. It is the second largest bank in France, ...

*

ING Bank

*

Mizuho Financial Group

The , known from 2000 to 2003 as Mizuho Holdings and abbreviated as MHFG or simply Mizuho, is a Japanese banking holding company headquartered in the Ōtemachi district of Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. The group was formed in 2000-2002 by merger of Dai- ...

*

Morgan Stanley

Morgan Stanley is an American multinational investment bank and financial services company headquartered at 1585 Broadway in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. With offices in 42 countries and more than 80,000 employees, the firm's clients in ...

*

Royal Bank of Canada

Royal Bank of Canada (RBC; ) is a Canadian multinational Financial institution, financial services company and the Big Five (banks), largest bank in Canada by market capitalization. The bank serves over 20 million clients and has more than ...

*

Banco Santander

Banco Santander S.A. trading as Santander Group ( , , ), is a Spanish multinational financial services company based in Santander, with operative offices in Madrid. Additionally, Santander maintains a presence in most global financial centres ...

*

Société Générale

Société Générale S.A. (), colloquially known in English-speaking countries as SocGen (), is a French multinational universal bank and financial services company founded in 1864. It is registered in downtown Paris and headquartered nearby i ...

*

Standard Chartered

Standard Chartered PLC is a British multinational bank with operations in wealth management, corporate and investment banking, and treasury services. Despite being headquartered in the United Kingdom, it does not conduct retail banking in th ...

*

State Street Corporation

*

Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation

is a Japanese multinational banking financial services institution owned by the Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, which is also known as the SMBC Group. It is headquartered in the same building as SMBC Group in Marunouchi, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. ...

*

Toronto-Dominion Bank

Toronto-Dominion Bank (), doing business as TD Bank Group (), is a Canadian multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. The bank was created on February 1, 1955, through the merger of the Bank of ...

*

UBS

*

UniCredit

UniCredit S.p.A. (formerly UniCredito Italiano S.p.A.) is an Italian multinational banking group headquartered in Milan. It is a systemically important bank (according to the list provided by the Financial Stability Board in 2022) and the world' ...

*

Wells Fargo

Wells Fargo & Company is an American multinational financial services company with a significant global presence. The company operates in 35 countries and serves over 70 million customers worldwide. It is a systemically important fi ...

*Note: ''In the wake of the

2023 banking crisis, the Swiss government facilitated an

acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS to avoid the former's collapse. UBS completed the acquisition in June 2023, thereby making Credit Suisse the first failure of a bank considered "too big to fail" since the

2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

.''

Notable views on the issue

Economists

More than fifty notable economists, financial experts, bankers, finance industry groups, and banks themselves have called for breaking up large banks into smaller institutions.

(See also

Divestment

In finance and economics, divestment or divestiture is the reduction of some kind of asset for financial, ethical, or political objectives or sale of an existing business by a firm. A divestment is the opposite of an investment. Divestiture is a ...

.)

Some economists such as

Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman ( ; born February 28, 1953) is an American New Keynesian economics, New Keynesian economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the CUNY Graduate Center, Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He ...

hold that bank crises arise from banks being under regulated rather than their size in itself. Krugman wrote in January 2010 that it was more important to reduce bank risk taking (leverage) than to break them up.

Economist

Simon Johnson has advocated both increased regulation as well as breaking up the larger banks, not only to protect the financial system but to reduce the political power of the largest banks.

Government officials

On March 6, 2013,

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the Federal government of the United States, federal government. The attorney general acts as the princi ...

Eric Holder told the

Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

that the

Justice Department faces difficulty charging large banks with crimes because of the risk to the economy.

Four days later,

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas President

Richard W. Fisher wrote in advance of a speech to the

Conservative Political Action Conference

The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC ) is an annual political conference attended by Conservatism in the United States, conservative Activism, activists and officials from across the United States. CPAC is hosted by the American ...

that large banks should be

broken up into smaller banks, and both

Federal Deposit Insurance and

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

discount window

Discount may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Discount (band), punk rock band that formed in Vero Beach, Florida in 1995 and disbanded in 2000

* ''Discount'' (film), French comedy-drama film

* "Discounts" (song), 2020 single by American rapper C ...

access should end for large banks.

Ben Bernanke

Ben Shalom Bernanke ( ; born December 13, 1953) is an American economist who served as the 14th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014. After leaving the Federal Reserve, he was appointed a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Insti ...

, the

chairman of the Federal Reserve

The chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is the head of the Federal Reserve, and is the active executive officer of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The chairman presides at meetings of the Board.

...

from 2006 to 2014, said more bankers should have gone to jail.

Central bankers

Mervyn King, the governor of the

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

during 2003–2013, called for cutting "too big to fail" banks down to size, as a solution to the problem of banks having taxpayer-funded guarantees for their speculative investment banking activities. "If some banks are thought to be too big to fail, then, in the words of a distinguished American economist, they are too big. It is not sensible to allow large banks to combine high street retail banking with risky investment banking or funding strategies, and then provide an implicit state guarantee against failure."

Former Chancellor of the Exchequer

Alistair Darling

Alistair Maclean Darling, Baron Darling of Roulanish, (28 November 1953 – 30 November 2023) was a British politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer under prime minister Gordon Brown from 2007 to 2010. A member of the Labour Party ...

disagreed: "Many people talk about how to deal with the big banks – banks so important to the financial system that they cannot be allowed to fail, but the solution is not as simple, as some have suggested, as restricting the size of the banks".

Additionally,

Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He worked as a private adviser and provided consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates L ...

said that "If they're too big to fail, they're too big", suggesting U.S. regulators to consider breaking up large financial institutions considered "too big to fail". He added, "I don't think merely raising the fees or capital on large institutions or taxing them is enough ... they'll absorb that, they'll work with that, and it's totally inefficient and they'll still be using the savings."

International organizations

On April 10, 2013,

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

managing director

Christine Lagarde told the

Economic Club of New York "too big to fail" banks had become "more dangerous than ever" and had to be controlled with "comprehensive and clear regulation

ndmore intensive and intrusive supervision".

[United Press Internationa]

(UPI), "Lagarde: 'Too big to fail' banks 'dangerous'"

Retrieved April 13, 2013

Public opinion polls

Gallup reported in June 2013 that: "Americans' confidence in U.S. banks increased to 26% in June, up from the record low of 21% the previous year. The percentage of Americans saying they have 'a great deal' or 'quite a lot' of confidence in U.S. banks is now at its highest point since June 2008, but remains well below its pre-recession level of 41%, measured in June 2007. Between 2007 and 2012, confidence in banks fell by half—20 percentage points." Gallup also reported that: "When Gallup first measured confidence in banks in 1979, 60% of Americans had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in them—second only to the church. This high level of confidence, which hasn't been matched since, was likely the result of the strong U.S. banking system established after the 1930s Great Depression and the related efforts of banks and regulators to build Americans' confidence in that system."

Lobbying by banking industry

In the US, the banking industry spent over $100 million lobbying politicians and regulators between January 1 and June 30, 2011. Lobbying in the finance, insurance and real estate industries has risen annually since 1998 and was approximately $500 million in 2012.

Historical examples

Prior to the 2008 failure and bailout of multiple firms, there were "too big to fail" examples from 1763 when

Leendert Pieter de Neufville in Amsterdam and

Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky in Berlin failed, and from

the 1980s and 1990s. These included Continental Illinois and

Long-Term capital Management

Long-Term Capital Management L.P. (LTCM) was a highly leveraged hedge fund. In 1998, it received a $3.6 billion bailout from a group of 14 banks, in a deal brokered and put together by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

LTCM was founded in ...

.

Continental Illinois case

An early example of a bank rescued because it was "too big to fail" was the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company during the 1980s.

Distress

The

Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company experienced a fall in its overall asset quality during the early 1980s. Tight money,

Mexico's default (1982) and plunging oil prices followed a period when the bank had aggressively pursued commercial lending business, Latin American

syndicated loan

A syndicated loan is one that is provided by a group of lenders and is structured, arranged, and administered by one or several commercial banks or investment banks known as lead arrangers.

The syndicated loan market is the dominant way for l ...

business, and loan participation in the energy sector. Complicating matters further, the bank's funding mix was heavily dependent on large

certificates of deposit and foreign

money market

The money market is a component of the economy that provides short-term funds. The money market deals in short-term loans, generally for a period of a year or less.

As short-term securities became a commodity, the money market became a compo ...

s, which meant its depositors were more risk-averse than average retail depositors in the US.

Payments crisis

The bank held significant participation in highly speculative oil and gas loans of Oklahoma's

Penn Square Bank. When Penn Square failed in July 1982, the Continental's distress became acute, culminating with press rumors of failure and an investor-and-depositor

run in early May 1984. In the first week of the run, the

Fed permitted the Continental Illinois

discount window

Discount may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Discount (band), punk rock band that formed in Vero Beach, Florida in 1995 and disbanded in 2000

* ''Discount'' (film), French comedy-drama film

* "Discounts" (song), 2020 single by American rapper C ...

credits on the order of $3.6 billion. Still in significant distress, the management obtained a further $4.5 billion in credits from a syndicate of money center banks the following week. These measures failed to stop the run, and regulators were confronted with a crisis.

Regulatory crisis

The seventh-largest bank in the nation by deposits would very shortly be unable to meet its obligations. Regulators faced a tough decision about how to resolve the matter. Of the three options available, only two were seriously considered. Even banks much smaller than the Continental were deemed unsuitable for resolution by liquidation, owing to the disruptions this would have inevitably caused. The normal course would be to seek a purchaser (and indeed press accounts that such a search was underway contributed to Continental depositors' fears in 1984). However, in the tight-money

financial climate of the early 1980s, no purchaser was forthcoming.

Besides generic concerns of size, contagion of depositor panic and bank distress, regulators feared the significant disruption of national payment and settlement systems. Of special concern was the wide network of correspondent banks with high percentages of their capital invested in the Continental Illinois. Essentially, the bank was deemed "too big to fail", and the "provide assistance" option was reluctantly taken. The dilemma then became how to provide assistance without significantly unbalancing the nation's banking system.

Trying to stop the run

To prevent immediate

failure

Failure is the social concept of not meeting a desirable or intended objective, and is usually viewed as the opposite of success. The criteria for failure depends on context, and may be relative to a particular observer or belief system. On ...

, the Federal Reserve announced categorically that it would meet any

liquidity

Liquidity is a concept in economics involving the convertibility of assets and obligations. It can include:

* Market liquidity

In business, economics or investment, market liquidity is a market's feature whereby an individual or firm can quic ...

needs the Continental might have, while the

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) gave depositors and general creditors a full guarantee (not subject to the $100,000 FDIC deposit-insurance limit) and provided direct assistance of $2 billion (including participations). Money center banks assembled an additional $5.3 billion unsecured facility pending a resolution and resumption of more-normal business. These measures slowed, but did not stop, the outflow of deposits.

Controversy

In a

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

hearing afterwards, the then

Comptroller of the Currency

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is an independent bureau within the United States Department of the Treasury that was established by the National Currency Act of 1863 and serves to corporate charter, charter, bank regulation ...

C. T. Conover defended his position by admitting the regulators will not let the largest 11 banks fail.

Long-Term capital Management

Long-Term capital Management L.P. (LTCM) was a hedge fund management firm based in Greenwich, Connecticut, that used absolute-return trading strategies combined with high financial leverage. The firm's master hedge fund, Long-Term capital Portfolio L.P., collapsed in the late 1990s, leading to an agreement on September 23, 1998, among 14 financial institutions for a $3.6 billion recapitalization (bailout) under the supervision of the Federal Reserve.

LTCM was founded in 1994 by John W. Meriwether, the former vice-chairman and head of bond trading at Salomon Brothers. Members of LTCM's board of directors included Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton, who shared the 1997 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for a "new method to determine the value of derivatives". Initially successful with annualized returns of over 40% (after fees) in its first years, in 1998 it lost $4.6 billion in less than four months following the Russian financial crisis requiring financial intervention by the Federal Reserve, with the fund liquidating and dissolving in early 2000.

International

Canada

In March 2013, the

Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI; , BSIF) is an independent agency of the Government of Canada reporting to the Minister of Finance created "to contribute to public confidence in the Canadian financial system". ...

announced that Canada's six largest banks,

Bank of Montreal

The Bank of Montreal (, ), abbreviated as BMO (pronounced ), is a Canadian multinational Investment banking, investment bank and financial services company.

The bank was founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1817 as Montreal Bank, making it Canada ...

,

Bank of Nova Scotia,

Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce

The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC; ) is a Canadian Multinational corporation, multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered at CIBC Square in the Financial District, Toronto, Financial District of Toronto, Ont ...

,

National Bank of Canada

The National Bank of Canada () is the sixth largest commercial bank in Canada. It is headquartered in Montreal, and has branches in most Canadian provinces and 2.4 million personal clients. National Bank is the largest bank in Quebec, and the se ...

,

Royal Bank of Canada

Royal Bank of Canada (RBC; ) is a Canadian multinational Financial institution, financial services company and the Big Five (banks), largest bank in Canada by market capitalization. The bank serves over 20 million clients and has more than ...

and

Toronto-Dominion Bank

Toronto-Dominion Bank (), doing business as TD Bank Group (), is a Canadian multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. The bank was created on February 1, 1955, through the merger of the Bank of ...

, were too big to fail. Those six banks accounted for 90% of banking assets in Canada at that time. It noted that "the differences among the largest banks are smaller if only domestic assets are considered, and relative importance declines rapidly after the top five banks and after the sixth bank (National)."

New Zealand

Despite the government's assurances, opposition parties and some media commentators in New Zealand say that the largest banks are too big to fail and have an implicit government guarantee.

United Kingdom

George Osborne

George Gideon Oliver Osborne (born 23 May 1971) is a British retired politician and newspaper editor who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016 and as First Secretary of State from 2015 to 2016 in the Cameron government. A ...

, Chancellor of the Exchequer under

David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

(2010–2016), threatened to break up banks which are too big to fail.

The too-big-to-fail idea has led to legislators and governments facing the challenge of limiting the scope of these hugely important organizations, and regulating activities perceived as risky or speculative—to achieve this regulation in the UK, banks are advised to follow the UK's

Independent Commission on Banking Report.

See also

*

Brown–Kaufman amendment

*

Bulge bracket

*

Corporate welfare

Corporate welfare refers to government financial assistance, Subsidy, subsidies, tax breaks, or other favorable policies provided to private businesses or specific industries, ostensibly to promote economic growth, job creation, or other public b ...

*

Crony capitalism

Crony capitalism, sometimes also called simply cronyism, is a pejorative term used in political discourse to describe a situation in which businesses profit from a close relationship with state power, either through an anti-competitive regul ...

*

Dirigisme

Dirigisme or dirigism () is an economic doctrine in which the state plays a strong directive (policies) role, contrary to a merely regulatory or non-interventionist role, over a market economy. As an economic doctrine, dirigisme is the opposite ...

*

Greenspan put

*

Lemon socialism

*

Liquidity trap

A liquidity trap is a situation, described in Keynesian economics, in which, "after the rate of interest has fallen to a certain level, liquidity preference may become virtually absolute in the sense that almost everyone prefers holding cash rathe ...

*

Speculative bubble

Speculative may refer to:

In arts and entertainment

*Speculative art (disambiguation)

*Speculative fiction, which includes elements created out of human imagination, such as the science fiction and fantasy genres

** Speculative Fiction Group, a Pe ...

*

Too connected to fail

Banking collapse

*

List of bank failures in the United States (2008–present)

*

List of banks acquired or bankrupted in the United States during the 2008 financial crisis

*

List of largest bank failures in the United States

General

*

Corporatocracy

Corporatocracy or corpocracy is an economic, political and judicial system controlled or influenced by business corporations or corporate Interest group, interests.

The concept has been used in explanations of bank bailouts, excessive pay for ...

*

Lender of last resort

In public finance, a lender of last resort (LOLR) is a financial entity, generally a central bank, that acts as the provider of liquidity to a financial institution which finds itself unable to obtain sufficient liquidity in the interbank ...

*

Zombie company

In political economy, a zombie company is a company that needs bailouts in order to operate, or an indebted company that is able to repay the interest on its debts but not repay the principal.

Description

Zombie companies are indebted businesses ...

, and

zombie bank

A zombie bank is a financial institution that has an economic net worth of less than zero but continues to operate because its ability to repay its debts is shored up by implicit or explicit government credit support.

The term was first used b ...

Works

* ''

Too Big to Fail (book)''

* ''

Too Big to Fail (film)

''Too Big to Fail'' is a 2011 American biographical drama television film directed by Curtis Hanson and written by Peter Gould, based on Andrew Ross Sorkin's 2009 non-fiction book ''Too Big to Fail''. The cast includes William Hurt, Edward ...

''

* ''

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail''

Notes

Further reading

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Who is Too Big to Fail?: Does Title II of the Dodd–Frank Act Enshrine Taxpayer Funded Bailouts?: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, First Session, May 15, 2013Who Is Too Big To Fail: Are Large Financial Institutions Immune from Federal Prosecution?: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House Of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, First Session, May 22, 2013Federal Reserve – List of Banks with Assets Greater than $10 billion

{{Wealth, state=autocollapse

History of the Federal Reserve System

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Bank regulation in the United States

Banking crises

Great Recession

Matthew effect

Quotations from business

1984 quotations

"Too big to fail" (TBTF) is a

"Too big to fail" (TBTF) is a

Bank size, complexity, and interconnectedness with other banks may inhibit the ability of the government to resolve (wind-down) the bank without significant disruption to the financial system or economy, as occurred with the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008. This risk of "too big to fail" entities increases the likelihood of a government bailout using taxpayer dollars.

The largest U.S. banks continue to grow larger while the concentration of bank assets increases. The largest six U.S. banks had assets of $9,576 billion as of year-end 2012, per their 2012 annual reports (SEC Form 10K). The top 5 U.S. banks had approximately 30% of the U.S. banking assets in 1998; this rose to 45% by 2008 and to 48% by 2010, before falling to 47% in 2011.

This concentration continued despite the

Bank size, complexity, and interconnectedness with other banks may inhibit the ability of the government to resolve (wind-down) the bank without significant disruption to the financial system or economy, as occurred with the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008. This risk of "too big to fail" entities increases the likelihood of a government bailout using taxpayer dollars.

The largest U.S. banks continue to grow larger while the concentration of bank assets increases. The largest six U.S. banks had assets of $9,576 billion as of year-end 2012, per their 2012 annual reports (SEC Form 10K). The top 5 U.S. banks had approximately 30% of the U.S. banking assets in 1998; this rose to 45% by 2008 and to 48% by 2010, before falling to 47% in 2011.

This concentration continued despite the  The United States passed the Dodd–Frank Act in July 2010 to help strengthen regulation of the financial system in the wake of the

The United States passed the Dodd–Frank Act in July 2010 to help strengthen regulation of the financial system in the wake of the