Suffragette Bombing And Arson Campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The suffragettes had invented the letter bomb, a device intended to kill or injure the recipient, and an increasing amount began to be posted. On 29 January, several letter bombs were sent to the

The suffragettes had invented the letter bomb, a device intended to kill or injure the recipient, and an increasing amount began to be posted. On 29 January, several letter bombs were sent to the

On 4 April, the day after Emmeline Pankhurst was sentenced to 3 years in prison for her role in the bombing of Lloyd George's house, a suffragette bomb was discovered in the street outside the

On 4 April, the day after Emmeline Pankhurst was sentenced to 3 years in prison for her role in the bombing of Lloyd George's house, a suffragette bomb was discovered in the street outside the  During this time, elderly suffragette ladies had reportedly begun to apply for gun licenses, supposedly to "terrify the authorities". On 14 April, the former home of MP

During this time, elderly suffragette ladies had reportedly begun to apply for gun licenses, supposedly to "terrify the authorities". On 14 April, the former home of MP

In early June 1913, a series of fires purposely started in rural areas in

In early June 1913, a series of fires purposely started in rural areas in

Arson and bombing attacks continued into 1914. One of the first attacks of the year took place on 7 January, when a

Arson and bombing attacks continued into 1914. One of the first attacks of the year took place on 7 January, when a  One common target for suffragette attacks was churches, as it was believed that the

One common target for suffragette attacks was churches, as it was believed that the

At the conclusion of the campaign in August 1914, the attacks had, in total, cost approximately £700,000 in damages (), although according to historian C. J. Bearman this figure does not include "the damage done to works of art or the more minor forms of militancy such as window-smashing and letter-burning". Bearman also notes that this figure does not include the extra costs inflicted by violent suffragette action, "such as extra police time, additional caretakers and night watchmen hired to protect property, and revenue lost when

At the conclusion of the campaign in August 1914, the attacks had, in total, cost approximately £700,000 in damages (), although according to historian C. J. Bearman this figure does not include "the damage done to works of art or the more minor forms of militancy such as window-smashing and letter-burning". Bearman also notes that this figure does not include the extra costs inflicted by violent suffragette action, "such as extra police time, additional caretakers and night watchmen hired to protect property, and revenue lost when

Suffragettes

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to member ...

in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

orchestrated a bombing and arson campaign between the years 1912 and 1914. The campaign was instigated by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was a part of their wider campaign for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. The campaign, led by key WSPU figures such as Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

, targeted infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

, government, churches and the general public, and saw the use of improvised explosive devices, arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wate ...

, letter bombs

A letter bomb, also called parcel bomb, mail bomb, package bomb, note bomb, message bomb, gift bomb, present bomb, delivery bomb, surprise bomb, postal bomb, or post bomb, is an explosive device sent via the postal service, and designed with ...

, assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

attempts and other forms of direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

and violence. At least 5 people were killed in such attacks (including one suffragette), and at least 24 were injured (including two suffragettes). The campaign was halted at the outbreak of war in August 1914 without having brought about votes for women, as suffragettes pledged to pause their campaigning to aid the nation's war effort.

The campaign has seen classification as a terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

campaign, with both suffragettes themselves and the authorities referring to arson and bomb attacks as terrorism. Contemporary press reports also referred to attacks as "terrorist" incidents in both the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, and a number of historians have also classified the campaign as one involving terrorist acts, such as C. J. Bearman, Fern Riddell

Fern Riddell ( ) (born 22 January 1986) is a British historian who specialises in gender, sex, suffrage and Victorian culture. She has written several popular history books and is a former columnist for the ''BBC History'' magazine.

Early life ...

, Rachel Monaghan and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

historian Cheryl Jorgensen-Earp. However, historian June Purvis

June Purvis is an emeritus professor of women's and gender history at the University of Portsmouth.

From 2014-18, Purvis was Chair of the Women’s History Network UK and from 2015-20 Treasurer of the International Federation for Research in Wo ...

has publicly contested the term and argued that the campaign did not involve terrorist acts.

Background

Multiple suffrage societies had formed across Britain during theVictorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

, all campaigning for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

- with only certain men being able to vote in parliamentary elections

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

at the time. In the years leading up to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, "suffragettes" had become the popular name for members of a new organisation, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

and her daughters, the Union was willing to carry out forms of direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

to achieve women's suffrage. This was indicated by the Union's adoption of the motto "deeds, not words".

After decades of peaceful protest, the WSPU believed that more radical action was needed to get the government to listen to the campaign for women's rights. From 1905 the WSPU's activities became increasingly militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin ...

and its members became increasingly willing to break the law, inflicting damage upon property and people. WSPU supporters raided Parliament, physically assaulted politicians and smashed windows at government premises. In one instance, a suffragette assaulted future Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

with a horse whip on the platform at Bristol railway station. Other militant suffragette groups were active: the Women's Freedom League

The Women's Freedom League was an organisation in the United Kingdom which campaigned for women's suffrage and sexual equality. It was an offshoot of the militant suffragettes after the Pankhursts decide to rule without democratic support fro ...

attacked ballot boxes at the 1909 Bermondsey by-election with acid, blinding the returning officer in one eye and causing severe burns to the Liberal agent's neck. However, before 1911, the WSPU made only sporadic use of violence, and it was directed almost exclusively at the government and its civil servants

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

. Emily Davison, the suffragette who later became infamous after she was killed by the King's horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby

The 1913 Epsom Derby, sometimes referred to as “The Suffragette Derby”, was a horse race which took place at Epsom Downs on 4 June 1913. It was the 134th running of the Derby. The race was won, controversially, by Aboyeur at record 100–1 ...

, had launched several sole attacks in London in December 1911, but these attacks were uncommon at this time. On 8 December 1911, Davison attempted to set fire to the busy post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional se ...

in Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a major street mostly in the City of London. It runs west to east from Temple Bar at the boundary with the City of Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the London Wall and the River Fleet from which the street was n ...

by placing a burning cloth soaked in kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning " wax", and was re ...

and contained in an envelope into the building, but the intended fire did not take hold. Six days later, Davison set fire to two pillar boxes in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, before again attempting to set fire to a post office in Parliament Street, but she was arrested during the act and imprisoned.

After 1911, suffragette violence was directed increasingly at commercial concerns and then at the general public. This violence was encouraged by the leadership of the WSPU. In particular, the daughter of WSPU leader Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

, Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), she directed its militant actions from exil ...

, took an active role in planning a self-described "reign of terror". Emmeline Pankhurst stated that the aim of the campaign was "to make England and every department of English life insecure and unsafe".

The campaign

Start of the campaign

In June and July 1912, five serious incidents signified the beginning of the campaign in earnest: the homes of three anti-suffrage cabinet ministers were attacked, a powerful bomb was planted in theHome Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

's office and the Theatre Royal, Dublin, was set fire to and bombed while an audience attended a performance. One of the most dangerous attacks committed by the suffragettes, the attack on the Theatre Royal was carried out by Mary Leigh

Mary Leigh (née Brown; 1885–1978) was an English political activist and suffragette.

Life

Leigh was born as Mary or Marie Brown in 1885. She was born in Manchester and was a schoolteacher until her marriage to a builder, surnamed Leigh. She j ...

, Gladys Evans, Lizzie Baker and Mabel Capper

Mabel Henrietta Capper (23 June 1888 – 1 September 1966) was a British suffragette. She gave all her time between 1907 and 1913 to the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) as a 'soldier' in the struggle for women's suffrage. She was impr ...

, who attempted to set fire to the building during a packed lunchtime matinee attended by the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

. A canister of gunpowder was left close to the stage and petrol and lit matches were thrown into the projection booth which contained highly combustible film reels. Earlier in the day, Mary Leigh had hurled a hatchet towards Asquith, which narrowly missed him and instead cut the Irish MP John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from ...

on the ear. The four suffragettes who carried out the attack on the Theatre Royal were subsequently charged with offences likely to endanger life.

Arson attacks continued for the rest of 1912. On 25 October, Hugh Franklin set fire to his train carriage as it pulled into Harrow station. He was subsequently arrested and charged with endangering the safety of passengers. Then, on 28 November, post boxes were booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or another animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap m ...

ped across Great Britain, starting a 5-day long pillar box sabotage campaign, with dangerous chemicals being poured into some boxes. In London, meanwhile, many letters ignited while in transit at post offices, and paraffin and lit matches were also put in pillar boxes.'Hundreds of Letters Are Damaged', ''Dundee Courier'', 29 November 1912"Suffragette Outrages", ''North Devon Journal'', 5 December 1912 On 29 November, a bystander was assaulted with a whip

A whip is a tool or weapon designed to strike humans or other animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain. They can also be used without inflicting pain, for audiovisual cues, such as in equestrianism. They are generally ...

at Aberdeen railway station

, symbol_location = gb

, symbol = rail

, image = Aberdeen station 01, August 2013.JPG

, caption = Concourse at Aberdeen station (2013)

, borough = Aberdeen, City of Aberdeen

, country = Scotland

, coordinates =

, grid_name = Grid refe ...

by Emily Davison, as she believed the man was politician David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

in disguise. On 17 December, railway signals at Potters Bar were tied together and disabled by suffragettes with the intention of endangering train journeys.

The increasing number of arson attacks and acts of criminal damage was criticised by some members of the WSPU, and in October 1912 two long-standing supporters of the suffragette cause, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (; 21 October 1867 – 11 March 1954) was a British women's rights activist and suffragette.

Early life

Pethick-Lawrence was born in Bristol as Emmeline Pethick. Her father, Henry Pethick, ...

and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence

Frederick William Pethick-Lawrence, 1st Baron Pethick-Lawrence, PC (né Lawrence; 28 December 1871 – 10 September 1961) was a British Labour politician who, among other things, campaigned for women's suffrage.

Background and education

B ...

, were expelled from the Union for voicing their objections to such activities. By the end of the year, 240 people had been sent to prison for militant suffragette activities.

Christabel Pankhurst set up a new weekly WSPU newspaper at this time named ''The Suffragette''. The newspaper began devoting double-page spreads to reporting the bomb and arson attacks that were now regularly occurring around the country. This became the method by which the organisation claimed responsibility for each attack. The independent press also began to publish weekly round-ups of the attacks, with some newspapers such as the ''Gloucester Journal'' and ''Liverpool Echo'' running dedicated columns on the latest "outrages".

January 1913 escalation

Despite the outbreak of violence, at the start of January 1913 suffragettes still believed that there were some hopes of achieving the vote for women by constitutional means. A "Franchise Bill" was proposed to the House of Commons in the winter session of 1912–13, and it was drafted to allow a series of amendments which, if passed, would have introduced women's suffrage. However, after an initial debate on 24 January, thespeaker of the house

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

ruled the amendments out of order and the government was forced to abandon the Bill. In response, the WSPU stepped-up their bombing and arson campaign. The subsequent campaign was directed and in some cases orchestrated by the WSPU leadership, and was specifically designed to terrorise the government and the general public to change their opinions on women's suffrage under threat of acts of violence. In a speech, leader Emmeline Pankhurst declared "guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

".

The suffragettes had invented the letter bomb, a device intended to kill or injure the recipient, and an increasing amount began to be posted. On 29 January, several letter bombs were sent to the

The suffragettes had invented the letter bomb, a device intended to kill or injure the recipient, and an increasing amount began to be posted. On 29 January, several letter bombs were sent to the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

, and the prime minister Asquith, but they all exploded in post offices, post boxes or in mailbags while in transit across the country. In the following weeks, further attacks on letters and mailboxes occurred in cities such as Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, London, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

, and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. On 6 February five postmen were burned, four severely, in Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

when handling a phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

suffragette letter bomb addressed to Asquith. On 19 February, there was a suffragette bomb attack on Lloyd George's house, with two bombs being planted by Emily Davison. Only one of the bombs functioned but the building was seriously damaged, although nobody was injured. The explosion of the bomb occurred shortly before the arrival of workmen at the house, and the crude nature of the timer – a candle

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammable solid substance such as tallow, that provides light, and in some cases, a fragrance. A candle can also provide heat or a method of keeping time.

A person who makes candle ...

– meant that the likelihood of the bomb exploding while the men were present was high. WSPU Leader Emmeline Pankhurst was herself arrested in the aftermath for planning the attack on Lloyd George's house, and was later sentenced to three years in prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

. Between February and March, railway signal wires were purposely cut on lines across the country, further endangering train journeys.

Some of the inspiration for the suffragettes' attacks came from the earlier Fenian dynamite campaign of 1881 to 1885. Although more sophisticated explosive devices were used by suffragettes, inspiration was taken from this campaign's tactic of targeting symbolic locations, such as the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

and St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

. Amongst the other targets selected by suffragettes were sporting events: there was a failed attempt to burn down the grounds of the All England Lawn Tennis Club

The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, also known as the All England Club, based at Church Road, Wimbledon, London, England, is a private members' club. It is best known as the venue for the Wimbledon Championships, the only Grand Slam ...

at Wimbledon, while a plot to burn down the grandstand

A grandstand is a normally permanent structure for seating spectators. This includes both auto racing and horse racing. The grandstand is in essence like a single section of a stadium, but differs from a stadium in that it does not wrap al ...

of Crystal Palace F.C.'s football ground on the eve of the 1913 FA Cup Final was also foiled. During the year the grandstand of the Manor Ground football stadium in Plumstead

Plumstead is an area in southeast London, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich, England. It is located east of Woolwich.

History

Until 1965, Plumstead was in the historic county of Kent and the detail of much of its early history can ...

was also burned down, costing £1,000 in damages. The destroyed ground was the home of then south London club Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostl ...

(known as Woolwich Arsenal until 1914), and the same year the financially-troubled club moved from south London to a new stadium in an area of north London, Highbury, where they still remain today. Suffragettes also attempted to burn the grandstands at the stadiums of Preston North End

Preston North End Football Club, commonly referred to as Preston, North End or PNE, is a professional football club in Preston, Lancashire, England, who currently play in the EFL Championship, the second tier of the English football league syste ...

and Blackburn Rovers football clubs during the year. More traditionally masculine

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some behaviors ...

sports were specifically targeted in an attempt to protest against male dominance. One sport that was often targeted was golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping wi ...

, and golf courses were often subjected to arson attacks. During some of these attacks Prime Minister Asquith would be physically assaulted while playing the sport.

Response to Emmeline Pankhurst's imprisonment

On 4 April, the day after Emmeline Pankhurst was sentenced to 3 years in prison for her role in the bombing of Lloyd George's house, a suffragette bomb was discovered in the street outside the

On 4 April, the day after Emmeline Pankhurst was sentenced to 3 years in prison for her role in the bombing of Lloyd George's house, a suffragette bomb was discovered in the street outside the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

. It was defused before it could detonate in what was then one of the busiest public streets in the capital, which likely prevented many casualties. The remains of the device are now on display at the City of London Police Museum in London. Railways were also the subject of bombing attacks at this time. On 3 April, a bomb exploded next to a passing train in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

, nearly killing the driver when flying debris grazed him and narrowly missed his head. Six days later, two bombs were left on the Waterloo to Kingston line, with one being placed on the eastbound train and the other on the westbound train. One of the bombs was discovered before it exploded at Battersea

Battersea is a large district in south London, part of the London Borough of Wandsworth, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross and extends along the south bank of the River Thames. It includes the Battersea Park.

History

Batt ...

when the railway porter spotted smoke in a previously crowded third-class carriage. Later in the day, as the Waterloo train pulled into Kingston, the third-class carriage exploded and caught fire. The rest of the carriages were full of passengers at the time, but they managed to escape without serious injury. The bombs had been packed with lumps of jagged metal, bullets and scraps of lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

. The London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The ...

was also targeted: on 2 May a highly unstable nitroglycerine bomb was discovered on the platform at Piccadilly Circus tube station

Piccadilly Circus is a London Underground station located directly beneath Piccadilly Circus itself, with entrances at every corner. Located in Travel-card Zone 1, the station is on the Piccadilly line between Green Park and Leicester Squa ...

. Although it had the potential to harm many members of the public on the platform, the bomb was dealt with. On 11 April, the cricket pavilion at the Nevill Ground in Royal Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in Kent, England, southeast of central London. It lies close to the border with East Sussex on the northern edge of the High Weald, whose sandstone geology is exemplified by the rock formation High Rocks ...

was destroyed in a suffragette arson attack. At many of the attacks, copies of ''The Suffragette'' newspaper were intentionally left at the scene, or postcards scrawled with messages such as "Votes For Women", as a way of claiming responsibility for the attacks.

The high explosive nitroglycerine was used for a number of suffragette bombs, and was likely produced by themselves in their own labs by sympathisers. The explosive is distinctly unstable, and nitroglycerine bombs could be detonated by as little as a sharp blow, making the bombs highly dangerous.

During this time, elderly suffragette ladies had reportedly begun to apply for gun licenses, supposedly to "terrify the authorities". On 14 April, the former home of MP

During this time, elderly suffragette ladies had reportedly begun to apply for gun licenses, supposedly to "terrify the authorities". On 14 April, the former home of MP Arthur Du Cros

Sir Arthur Philip Du Cros, 1st Baronet (26 January 1871 – 28 October 1955) was a British industrialist and politician.

Early life and education

Du Cros was born in Dublin on 26 January 1871, the third of seven sons of Harvey du Cros and his ...

was burned down. Du Cros had consistently voted against the enfranchisement of women, which was why he had been chosen as a target. The immediate aftermath of the destruction of Du Cros's house was caught on film, with newsreel company Pathé

Pathé or Pathé Frères (, styled as PATHÉ!) is the name of various French businesses that were founded and originally run by the Pathé Brothers of France starting in 1896. In the early 1900s, Pathé became the world's largest film equipment ...

filming the ruins while they were still smouldering. Some newspapers were also targeted by suffragettes: on 20 April there was an attempt to blow up the offices of the ''York Herald'' in York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

.

One bomb that was found in Smeaton's Tower

Smeaton's Tower is a memorial to civil engineer John Smeaton, designer of the third and most notable Eddystone Lighthouse. A major step forward in lighthouse design, Smeaton's structure was in use from 1759 to 1877, until erosion of the ledge i ...

on Plymouth Hoe during April was found to have "Votes For Women. Death in Ten Minutes" written on it. On 8 May, a potassium nitrate

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and ...

bomb was discovered at St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

at the start of a sermon. The bomb likely would have destroyed the historic bishop's throne and other parts of the cathedral had it exploded. Meanwhile, suffragette action continued to cause injury to postal workers, with three London postmen being injured after coming into contact with noxious chemicals that had been poured into pillar boxes. On 14 May, a letter bomb was sent to allegedly anti-women's suffrage magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

Sir Henry Curtis-Bennett

Sir Henry Honywood Curtis-Bennett, KC (31 July 1879 – 2 November 1936) was an English barrister and Conservative Party politician. As a barrister, he led the defence in the 1922 cases of Herbert Rowse Armstrong and of Edith Thompson and Fred ...

at Bow Street in an attempt to assassinate him, but the bomb was intercepted by London postal workers. Suffragettes again attempted to assassinate Curtis-Bennett by pushing him off a cliff two days later at Margate

Margate is a seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay and Westbrook.

The town has been a significan ...

, although he managed to escape. The railways continued to be the subject of significant attacks throughout May. On 10 May, a bomb was discovered in the waiting room at Liverpool Street Station

Liverpool Street station, also known as London Liverpool Street, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in the north-eastern corner of the City of London, in the ward of Bishopsgate Without. It is the ...

, London, covered with iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

nuts and bolts intended to maximise damage to property and cause serious injury to anyone in proximity. Four days later, another three suffragette bombs were discovered in the third-class carriage of a crowded passenger train arriving from Waterloo at Kingston, made out of nitroglycerine. On 16 May, a second attempted bombing of the London Underground was foiled when a bomb was discovered at Westbourne Park tube station before it could explode. Another attack on the railways occurred on 27 May, when a suffragette bomb was thrown from an express train onto Reading station

Reading railway station is a major transport hub in Reading, Berkshire, England. It is on the northern edge of the town centre, near the main retail and commercial areas and the River Thames, from .

Reading is the ninth-busiest station in ...

platform and exploded, but there were no injuries.

During the month of May, 52 bombing and arson attacks had been carried out across the country by suffragettes.

Targeting of houses

The most common target for suffragette attacks during the campaign was houses or residential properties belonging to politicians or members of the public. These attacks were justified by the WSPU on the grounds that the owners of the properties were invariably male, and so already possessed the vote. Since they already possessed the vote, suffragettes argued, the owners were responsible for the actions of the government since they were their electors. Houses were bombed or subjected to arson attacks around the country: in March 1913, fires raged at private homes across Surrey, and homes in Chorley Wood,Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

, Potters Bar and Hampstead Garden were also set on fire. In Ilford, London, three residential streets had their fire alarm wires cut. Other prominent opponents of women's suffrage also saw their homes destroyed by fire and incendiary devices, sometimes as a response to police raids on WSPU offices. Relatives of politicians also saw their houses attacked: the Mill House near Liphook, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

was burned because the owner was Reginald McKenna's brother Theodore, while a bomb was set off in a house in Moor Hall Green, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, as the property was owned by Arthur Chamberlain, brother of Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

politician Joseph Chamberlain (father to future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

). Houses were also attacked in Doncaster

Doncaster (, ) is a city in South Yorkshire, England. Named after the River Don, it is the administrative centre of the larger City of Doncaster. It is the second largest settlement in South Yorkshire after Sheffield. Doncaster is situated in ...

. After some suffragettes were thrown out of a political meeting there in June 1913, the house of the man who had thrown them out was burned down. In response to such actions, angry mobs often attacked WSPU meetings, such as in May 1913 when 1,000 people attacked a WSPU meeting in Doncaster. In retaliation, suffragettes burned down more properties in the local area.

Deaths and further injuries

In early June 1913, a series of fires purposely started in rural areas in

In early June 1913, a series of fires purposely started in rural areas in Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

killed at least two men, as well as several horses. The acts were officially "claimed" by the suffragettes in their official newspaper, ''The Suffragette''. Over the next few months, suffragette attacks continued to threaten death and injury. On 2 June, a suffragette bomb was discovered at the South Eastern District Post Office, London, containing enough nitroglycerine to blow up the entire building and kill the 200 people who worked there. A potentially serious event was avoided on 18 June when a suffragette bomb narrowly failed to breach the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal in Yardley Wood

Yardley may refer to:

People Surname

* Bruce Yardley (1947–2019), Australian cricketer

* David Yardley (1929–2014), British legal scholar and public servant

* Doyle Yardley (1913–1946), American military officer

* Eric Yardley (born 1990), ...

, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

. Since there was no lock for 11 miles, a breach would have emptied all this section's water into the populated valley below, which likely would have caused a loss of life. The next day, a suffragette named Harry Hewitt pulled out a revolver

A revolver (also called a wheel gun) is a repeating firearm, repeating handgun that has at least one gun barrel, barrel and uses a revolving cylinder (firearms), cylinder containing multiple chamber (firearms), chambers (each holding a single ...

at the Ascot Gold Cup

The Gold Cup is a Group 1 flat horse race in Great Britain open to horses aged four years or older. It is run at Ascot over a distance of 2 miles 3 furlongs and 210 yards (4,01 ...

horseracing event, entering the track during the race and brandishing the gun and a suffragette flag as the competing horses approached. The leading horse collided with the man, causing serious head injuries to him and the jockey

A jockey is someone who rides horses in horse racing or steeplechase racing, primarily as a profession. The word also applies to camel riders in camel racing. The word "jockey" originated from England and was used to describe the individual ...

. Hewitt was later impounded in a psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociat ...

. The incident was a copycat event inspired by the events of the Epsom Derby on 4 June 1913, where Emily Davison had famously entered the racecourse and threw herself in front of the King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

's personal horse, an incident which not only killed her but that seriously injured the jockey. On 19 July 1913, letter boxes were filled with noxious substances across Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, seriously burning a postman when he opened one box."Letter-boxes", ''Western Mail'', 21 July 1913, p. 5 On the same day, Edith Rigby

Edith Rigby ( Rayner) (18 October 1872 – 23 July 1950) was an English suffragette who used arson as a way to further the cause of women’s suffrage. She founded a night school in Preston called St Peter's School, aimed at educating women and ...

planted a pipe bomb at the Liverpool Cotton Exchange Building, which exploded in the public hall. After she was arrested, Rigby stated that she planted the bomb as she wanted "to show how easy it was to get explosives and put them in public places". On 8 August, a school in Sutton-in-Ashfield was bombed and burned down in protest while Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

was visiting the town, with the bombs later being found to have represented a potentially serious threat to life had anyone been present in the building at the time. Then, on 18 December, suffragettes bombed a wall at Holloway Prison in protest of the imprisonment of an inmate inside. Many houses near the prison were damaged or had their windows blown out by the bombs, showering some children with glass while they slept in their beds. One of the perpetrators of the attack was injured by the blast.

In one of the more serious suffragette attacks, a fire was purposely started at Portsmouth dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is ...

on 20 December 1913, in which 2 men were killed after it spread through the industrial area. In the midst of the firestorm, a battlecruiser, HMS '' Queen Mary'', had to be towed to safety to avoid the flames. Then, two days before Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

, several postal workers in Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

were severely burned after more suffragette letter bombs caused mail bags to ignite.

By the end of the year, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' newspaper reported that there had been 39 recorded suffragette bombing attacks across the country.

1914 attacks

Arson and bombing attacks continued into 1914. One of the first attacks of the year took place on 7 January, when a

Arson and bombing attacks continued into 1914. One of the first attacks of the year took place on 7 January, when a dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

bomb was thrown over the wall of the Harewood Army Barracks in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popul ...

, which was being used for police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

training at the time. The explosion of the bomb injured one man, while others narrowly escaped without being harmed after being thrown to the ground by the force of the bomb. An arson attack on Aberuchill Castle

Aberuchill Castle is located west of Comrie in Perthshire, Scotland. It comprises an early 17th-century tower house, which was extended and remodelled in the 19th century. The house, excluding the later west wing, is protected as a category A li ...

, Comrie, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

on 4 February also nearly caused fatalities. The building was set on fire with the servants inside, and they narrowly escaped harm. The next month, another cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

minister, Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

Reginald McKenna, had his house set on fire in an arson attack.

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

was complicit in reinforcing opposition to women's suffrage. Between 1913 and 1914, 32 churches were the subject of suffragette attacks. Several churches and cathedrals

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

were bombed in 1914: on 5 April, the St Martins-in-the-Field

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the me ...

church in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, London, was bombed, blowing out the windows and showering passers-by with broken glass. A bomb was also discovered in the Metropolitan Tabernacle church in London, and in June, a bomb exploded at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, damaging the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

. The Abbey was busy with visitors at the time, and around 80–100 people were in the building when the bomb exploded. The device was most probably planted by a member of a group that had left the Abbey only moments before the explosion. Some were as close as 20 yards from the bomb at the time and the explosion caused a panic for the exits, but no serious injuries were reported. The bomb had been packed with nuts and bolts to act as shrapnel. Coincidentally, at the time of the explosion, the House of Commons only 100 yards away was debating how to deal with the violent tactics of the suffragettes. Many in the Commons heard the explosion and rushed to the scene to find out what had happened. Two days after the Westminster Abbey bombing, a second suffragette bomb was discovered before it could explode in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

. Annie Kenney also attempted a second bombing of the Church of St John the Evangelist in Smith Square

Smith Square is a square in Westminster, London, 250 metres south-southwest of the Palace of Westminster. Most of its garden interior is filled by St John's, Smith Square, a Baroque surplus church, which has inside converted to a concert hall. ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

on 12 July, placing a bomb underneath a pew during a sermon before leaving. However, the bomb was spotted by a member of the congregation, and Kenney, who was already being trailed by special branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and intelligence in British, Commonwealth, Irish, and other police forces. A Special Branch unit acquires and develops intelligence, usu ...

detectives

A detective is an investigator, usually a member of a law enforcement agency. They often collect information to solve crimes by talking to witnesses and informants, collecting physical evidence, or searching records in databases. This leads th ...

, was arrested as she left. The congregation left in the church then was able to disarm the bomb before it exploded.

A hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergen ...

was also targeted in Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

on 22 May, with suffragettes burning down the building. Two planned assaults on public officials also occurred during the year: in March, the Medical Prisoner Commissioner for Scotland was assaulted by suffragettes in public with horse whips, and on 3 June the medical officer for Holloway Prison, Dr. Forward, was also assaulted in a public street with whips. Another individual was injured in July when a suffragette letter bomb ignited a moving train in Salwick. After the bomb caused a train carriage to catch fire, the train's guard attempted to throw the burning materials off the train to avoid further damage. In doing so, he was badly burned on his arms, although he succeeded in disposing of the material. Another attempt to flood a populated area had also taken place on 7 May, when a bomb was placed next to Penistone Reservoir in Upper Windleden. If successful, the attack would have led to 138 million gallons of water emptying into the populated valleys below, although the anticipated breech did not take place.

Aborted plots

Some attacks were voluntarily aborted before they were carried out. In March 1913, a suffragette plot to kidnap Home Secretary Reginald McKenna was discussed in the House of Commons and in the press. It was reported that suffragettes were contemplating kidnapping one or more cabinet ministers and subjecting them to force-feeding. According toSpecial Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and intelligence in British, Commonwealth, Irish, and other police forces. A Special Branch unit acquires and develops intelligence, usu ...

detectives, there were also WSPU plans in 1913 to create a suffragette "army", known as the "People's Training Corps". A detective reported attending a meeting in which 300 young girls and women gathered ready to be trained, supposedly with the eventual aim of proceeding in force to Downing Street to forcibly imprison ministers until they conceded women's suffrage. The group were nicknamed "Mrs Pankhurst's Army".

Outbreak of war and ending of the campaign

In August 1914 theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

began, which effectively led the end of the suffragette bombing and arson campaign. After Britain joined the war, the WSPU took the decision to suspend their own campaigning. Leader Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

instructed suffragettes to stop their violent actions and support the government in the conflict against Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. From this point forward, suffragettes instead largely channelled their energies into supporting the war effort. By the time of the outbreak of war, the aim of achieving votes for women was still unrealised. Later in the war, the increasing focus of the WSPU and the Pankhurst leadership on supporting the war effort led to the creation of the Women's Party, a political party that continued to promote women's suffrage but that was primarily concerned with patriotic support for the war.

Reaction to the campaign

General public

The violence employed by suffragettes caused angry reactions amongst some members of the general public, with some actions inciting violent responses in return. A month after the bombing attack on Lloyd George's house in February 1913, a WSPU rally was held in Hyde Park, London, but the meeting quickly degenerated into ariot

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

as members of the public became violent towards the women. Clods of earth were thrown and some of the women manhandled, with many shouting "incendiary" or "shopbreakers" at the WSPU members. This was not an isolated event, as attacks on individual's houses often saw angry responses, such as in Doncaster

Doncaster (, ) is a city in South Yorkshire, England. Named after the River Don, it is the administrative centre of the larger City of Doncaster. It is the second largest settlement in South Yorkshire after Sheffield. Doncaster is situated in ...

in May 1913 when a 1,000 strong mob descended upon a WSPU meeting after several residential properties were burned down in the area. After one attack on Bristol University

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

's sports pavilion on 23 October 1913, undergraduates revenged the attack by raiding the WSPU office in the city.

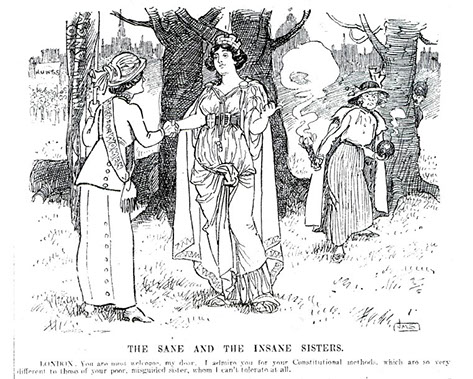

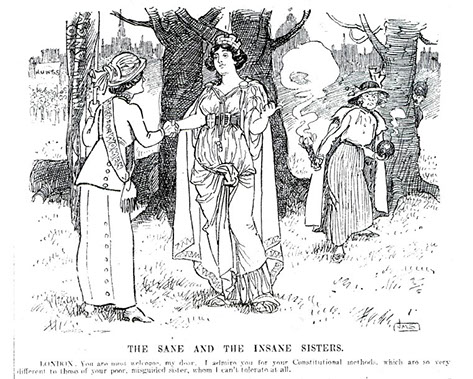

Wider women's suffrage movement

The "suffragists" of the largest women's suffrage society, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, led by Millicent Fawcett, were anti-violence, and during the campaign NUWSS propaganda and Fawcett herself increasingly differentiated between the militants of the WSPU and their own non-violent means. The NUWSS also publicly distanced themselves from the violence and direct action of suffragettes. The other major women's suffrage society, theWomen's Freedom League

The Women's Freedom League was an organisation in the United Kingdom which campaigned for women's suffrage and sexual equality. It was an offshoot of the militant suffragettes after the Pankhursts decide to rule without democratic support fro ...

, also opposed the violence publicly.

Special Branch response

The counter-terroristSpecial Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and intelligence in British, Commonwealth, Irish, and other police forces. A Special Branch unit acquires and develops intelligence, usu ...

of the police, which had been set up during the earlier Fenian dynamite campaign of 1881–1885, bore responsibility for dealing with the campaign. Special Branch officers were employed to cover WSPU meetings and demonstrations in order to pre-empt offences, provide public order intelligence and to record inflammatory speeches. WSPU leaders had been followed by Special Branch officers from 1907 onwards, and Emmeline Pankhurst herself was trailed by officers from the branch. A separate suffragette section of the branch had been formed in 1909.

During the campaign, attempts to attend WSPU meetings became increasingly difficult as officers were recognised and attacked. The attacks became so widespread that police had to invent new and never before attempted methods of counter-terrorism. These included the use of double agents

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

, covert photo surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

, public pleas for funding and the use of a secret bomb disposal

Bomb disposal is an explosives engineering profession using the process by which hazardous explosive devices are rendered safe. ''Bomb disposal'' is an all-encompassing term to describe the separate, but interrelated functions in the milit ...

unit on Duck Island in St James's Park, London. The branch was also given extra staff in order to protect ministers and their families, who were increasingly being targeted. Prime Minister Asquith wrote that "even our children had to be vigilantly protected against the menace of abduction". Many arrests were also made at WSPU meetings, and raids were often conducted against WSPU offices, in an attempt to find the bomb-makers arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostl ...

. In one raid on the home of Jennie Baines, a half-made bomb, a fully made bomb and guns were found. Raids were also conducted against the offices of ''The Suffragette'' newspaper, and the printers were threatened with prosecution. Because of this, there were periods that the newspaper could not publish, but secret reserves were kept for the newspaper to publish as many issues as possible.

At the time, planting bombs was officially a hangable offence, and so suffragettes took special measures to avoid being caught by police when carrying out bombing attacks.

Impact and effectiveness

At the conclusion of the campaign in August 1914, the attacks had, in total, cost approximately £700,000 in damages (), although according to historian C. J. Bearman this figure does not include "the damage done to works of art or the more minor forms of militancy such as window-smashing and letter-burning". Bearman also notes that this figure does not include the extra costs inflicted by violent suffragette action, "such as extra police time, additional caretakers and night watchmen hired to protect property, and revenue lost when

At the conclusion of the campaign in August 1914, the attacks had, in total, cost approximately £700,000 in damages (), although according to historian C. J. Bearman this figure does not include "the damage done to works of art or the more minor forms of militancy such as window-smashing and letter-burning". Bearman also notes that this figure does not include the extra costs inflicted by violent suffragette action, "such as extra police time, additional caretakers and night watchmen hired to protect property, and revenue lost when tourist attractions

A tourist attraction is a place of interest that tourists visit, typically for its inherent or an exhibited natural or cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, offering leisure and amusement.

Types

Places of natural ...

such as Haddon Hall

Haddon Hall is an English country house on the River Wye near Bakewell, Derbyshire, a former seat of the Dukes of Rutland. It is the home of Lord Edward Manners (brother of the incumbent Duke) and his family. In form a medieval manor house, ...

and the State Apartments at Windsor Castle were closed for fear of suffragette attacks". With these additional considerations, Bearman asserts, the campaign cost the British economy between £1 and £2 million in 1913 to 1914 alone (approximately £130–£240 million today). There was an average of 21 bombing and arson incidents per month in 1913, and 15 per month in 1914, with there being an arson or bombing attack in every month between February 1913 and August 1914. Bearman calculates that there was a total of at least 337 arson and bombing attacks between 1913 and 1914, but states that the true number could be well over 500. By the end of the campaign, more than 1,300 people had been arrested and imprisoned for suffragette violence across the United Kingdom.

The extent to which suffragette militancy contributed to the eventual enfranchisement of women in 1918 has been debated by historians, although the consensus of historical opinion is that the militant campaign was not effective. With the aim of gaining votes for women still unrealised by the outbreak of war in 1914, the WSPU had failed to create the kind of "national crisis" which might have forced the government into concessions. Historian Brian Harrison has also stated that opponents to women's suffrage believed the militant campaign had benefited them, since it had largely alienated public opinion and placed the suffrage question beyond parliamentary consideration. In May 1913 another attempt had been made to pass a bill in parliament which would introduce women's suffrage, but the bill actually did worse than previous attempts when it was voted on, something which much of the press blamed on the increasingly violent tactics of the suffragettes. The impact of the WSPU's violent attacks drove many members of the general public away from supporting the cause, and some members of the WSPU itself were also alienated by the escalation of violence, which led to splits in the organisation and the formation of groups such as the East London Federation of Suffragettes

The Workers' Socialist Federation was a socialist political party in the United Kingdom, led by Sylvia Pankhurst. Under many different names, it gradually broadened its politics from a focus on women's suffrage to eventually become a left co ...

in 1914. Bearman has asserted that contemporary opinion overwhelmingly was of the view that WSPU violence had shelved the question of women's suffrage until the organization "came to its senses or had disappeared from the scene". At the time it was largely only suffragettes themselves that argued their campaign had been effective.

In the 1930s, soon after all women over the age of 21 had received the vote under the Representation of the People Act of 1928, some historians asserted that militancy had evidently succeeded. The Suffragette Fellowship, which compiled the sources on the movement that were often used by later historians, also decided in this decade that they were not going to mention any of the bombings in any of the sources. This was partly in order to protect former suffragettes from prosecution, but was also an attempt to step away from the violent rhetoric and to change the cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.T ...

memory of the suffragette movement. Many official sources on suffragette violence are only now beginning to be released from archives

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located.

Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual o ...

.

Some feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

historians and supporters of feminist icon Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

such as Sandra Stanley Horton and June Purvis

June Purvis is an emeritus professor of women's and gender history at the University of Portsmouth.

From 2014-18, Purvis was Chair of the Women’s History Network UK and from 2015-20 Treasurer of the International Federation for Research in Wo ...

have also renewed the arguments that militancy succeeded, with Purvis arguing that assertions about the counter-productiveness of militancy deny or diminish the achievements of Pankhurst. However, Purvis's arguments have been challenged by Bearman. Revisionist historians

In historiography, historical revisionism is the reinterpretation of a historical account. It usually involves challenging the orthodox (established, accepted or traditional) views held by professional scholars about a historical event or time ...

such as Harrison and Martin Pugh have also attempted to draw greater attention to the role of the non-militants, such as those in the anti-violence National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) (known as "suffragists"), and emphasised their understated role in gaining votes for women.

Classification as terrorism

During the campaign, the WSPU described its own bombing and arson attacks asterrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

, with suffragettes declaring themselves to be "terrorists" in 1913. Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), she directed its militant actions from exil ...

also increasingly used the word "terrorism" to describe the WSPU's actions during the campaign, and stated that the WSPU's greater "rebellion" was a form of terrorism. Emmeline Pankhurst stated that the suffragettes committed violent acts because they wanted to "terrorise the British public". The WSPU also reported each of its attacks in its newspaper ''The Suffragette'' under the headline "Reign of Terror". The authorities talked of arson and bomb attacks as terrorism, and contemporary newspapers in the UK and in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

also made use of the term "Suffragette Terrorism" to report on WSPU attacks. One instance of this was after the bombing attack on David Lloyd George's house in February 1913, when the '' Pall Mall Gazette'' reported the attack under the specific headline of "Suffragette Terrorism".

The bombing and arson campaign has seen classification as a single-issue terrorism campaign by academics, and is classified as such in ''The Oxford Handbook of Terrorism''. Many historians have also asserted that the campaign contained terrorist acts. Rachel Monaghan published three articles in 1997, 2000 and 2007 in terrorism-themed academic journals in which she argued that the campaign can be described as one that was terrorist in nature. In 2005, historian C. J. Bearman published a study on the bombing and arson campaign in which he asserted: "The intention of the campaign was certainly terrorist in terms of the word's definition, which according to the ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' (1990 edition) is 'a person who uses or favours violent and intimidating methods of coercing a government or community'. The intention of coercing the community is clearly expressed in the WSPU's Seventh Annual Report, and, according to Annie Kenney, that of coercing Parliament was endorsed by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst themselves. The question is therefore not whether the campaign was terrorist, or whether the WSPU (in 1912–14) can be called a terrorist organization, but whether its terrorism worked." Bearman later published a further article in 2007 which also claims that the suffragette campaign was a terrorist one.

Fern Riddell