In linguistics, a small clause consists of a subject and its

predicate

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, o ...

, but lacks an overt expression of

tense.

Small clauses have the semantic subject-predicate characteristics of a

clause

In language, a clause is a constituent that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject and a syntactic predicate, the latter typically a verb phrase composed of a verb wit ...

, and have some, but not all, the properties of a

constituent

Constituent or constituency may refer to:

Politics

* An individual voter within an electoral district, state, community, or organization

* Advocacy group or constituency

* Constituent assembly

* Constituencies of Namibia

Other meanings

* Consti ...

. Structural analyses of small clauses vary according to whether a flat or layered analysis is pursued. The small clause is related to the phenomena of

raising-to-object,

exceptional case-marking Exceptional case-marking (ECM), in linguistics, is a phenomenon in which the subject of an embedded infinitival verb seems to appear in a superordinate clause and, if it is a pronoun, is unexpectedly marked with object case morphology (''him'' not ...

,

accusativus cum infinitivo In grammar, accusative and infinitive is the name for a syntactic construction of Latin and Greek, also found in various forms in other languages such as English and Spanish. In this construction, the subject of a subordinate clause is put in the ac ...

, and object

control

Control may refer to:

Basic meanings Economics and business

* Control (management), an element of management

* Control, an element of management accounting

* Comptroller (or controller), a senior financial officer in an organization

* Controlli ...

.

History

The two main analyses of small clauses originate with

Edwin Williams (1975, 1980) and Timothy Stowell (1981). Williams' analysis follows the Theory of Predication, where the "subject" is the "external argument of a maximal projection".

In contrast, Stowell's theory follows the Theory of Small Clauses, supported by linguists such as Chomsky, Aarts, and Kitagawa. This theory uses X-bar theory to treat small clauses as constituents. Linguists debate which analysis to pursue, as there is evidence for both sides of the debate.

Williams (1975, 1980)

The term "small clause" was coined by Edwin Williams in 1975, who specifically looked at "reduced relatives, adverbial modifier phrases, and gerundive phrases".

The following three examples are treated in Williams' 1975 paper as "small clauses", as cited in Balazs 2012.

However, not all linguists consider these to be small clauses according to the term's modern definition.

# ''The man''

''driving the bus'' ''is Norton's best friend.''

# ''John decided to leave,''

''thinking the party was over''

#

''John's evading his taxes'' ''infuriates me''.

The modern definition of a small clause is an

P XPin a predicative relationship. This definition was proposed by Edwin Williams in 1980, who introduced the concept of Predication.

He proposed that the subject NP and the predicate XP are related via co-indexation, which is made possible by c-command.

In Williams' analysis, the

P XPof a small clause does not form a constituent.

Stowell (1981)

Timothy Stowell in 1981 analyzed the small clause as a constituent,

[ pg. 87-88.] and proposed a structure using X-bar theory.

Stowell proposes that the subject is defined as an NP occurring in a specifier position, that case is assigned in the specifier position, and that not all categories have subjects.

His analysis explains why case-marked subjects cannot occur in infinitival clauses, although NPs can be projected up to an infinitival clause's specifier position.

Stowell considers the following examples to be small clauses and constituents.

#

''I consider'' ''John very stupid''

# ''I expect''

''that sailor off my ship'' # ''We feared''

''John killed by the enemy'' # ''I saw''

''John come to the kitchen'' ref name="Balazs 7">

Contexts

What does and does not qualify as a small clause varies in the literature: the example sentences in (8) contain (what some theories of syntax judge to be) small clauses. In each example, the posited small clause is in boldface, and the underlined expression functions as a predicate over the nominal immediately to its left, which is the subject. The verbs that license small clauses are a heterogeneous set, and fall into five classes:

* ''raising-to-object'' or ''

ECM

ECM may refer to:

Economics and commerce

* Engineering change management

* Equity capital markets

* Error correction model, an econometric model

* European Common Market

Mathematics

* Elliptic curve method

* European Congress of Mathemat ...

'' verbs like ''consider'' and ''want'' in (8a); these were the focus of early discussions of small clauses

* verbs like ''call'' and ''name'', which

subcategorize for an object NP and a

predicative expression

A predicative expression (or just predicative) is part of a clause predicate, and is an expression that typically follows a copula (or linking verb), e.g. ''be'', ''seem'', ''appear'', or that appears as a second complement of a certain type of ...

; see (8b)

* verbs like ''wipe'' and ''pound'', which allow the appearance of a resultative predicate; see (8c)

* perception verbs like ''see'' and ''hear'' which allow the appearance of a bare infinitive; see (8d)

* verbs like ''believe'' and ''judge'' which allow the appearance of infinitival ''to''; see (8e)

A trait that the examples in (8a-b-c) have in common is that the small clause lacks a verb. Indeed, this is sometimes taken as a defining aspect of small clauses, i.e. to qualify as a small clause, a verb must be absent.

If, however, one allows a small clause to contain a verb, then the sentences in (8d-e) can also be treated as containing small clauses:

The similarity across the sentences (8a-b-c) and (8d-e) is obvious, since the same subject-predicate relationship is present in all these sentences. Hence if one treats sentences (8a-b-c) as containing small clauses, one can also treat sentences (50e-f) as containing small clauses. A defining characteristic of all five contexts for English small clauses in (8a-b-c-d-e) is that the tense associated with finite clauses, which contain a

finite verb

Traditionally, a finite verb (from la, fīnītus, past participle of to put an end to, bound, limit) is the form "to which number and person appertain", in other words, those inflected for number and person. Verbs were originally said to be ''fin ...

, is absent.

Structural analyses

Broadly speaking, there are three competing analyses of the structure of small clauses.

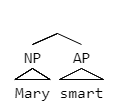

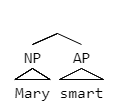

* the flat structure analysis treats the subject and predicate of the small clause as sister constituents

* the layered structure analysis treats the subject and predicate as a single "small clause" (SC) constituent

* the X-bar theory analysis treats the subject and predicate as a single constituent projected from the head of the small clause, which may be V, N, A, or P (with some analyses having additional functional structure)

Flat structure

The flat structure organizes small clause material into two distinct sister constituents.

The a-trees on the left are the phrase structure trees, and the b-trees on the right are the dependency trees. The key aspect of these structures is that the small clause material consists of two separate sister constituents.

The flat analysis is preferred by those working in dependency grammars and representational phrase structure grammars (e.g.

Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar and

Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG) is a highly lexicalized, constraint-based grammar

developed by Carl Pollard and Ivan Sag. It is a type of phrase structure grammar, as opposed to a dependency grammar, and it is the immediate successor ...

).

Layered structure

The layered structure organizes small clause material into one constituent. The phrase structure trees are again on the left, and the dependency trees on the right. To mark the small clause in the phrase structure trees, the node label SC is used.

The layered analysis is preferred by those working in the

Government and Binding

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government ...

framework and its tradition, for examples see Chomsky, Ouhalla,

Culicover,

Haegeman and Guéron.

X-Bar Theory structures

''

See X-Bar Theory

In linguistics, X-bar theory is a model of phrase-structure grammar and a theory of syntactic category formation that was first proposed by Noam Chomsky in 1970Chomsky, Noam (1970). Remarks on Nominalization. In: R. Jacobs and P. Rosenbaum (eds.) ...

for a general exploration of X-Bar Theory.''

X-bar theory predicts that a head (X) will project into an intermediate constituent (X') and a maximal projection (XP). There were three common analyses of the internal structure of a small clause under X-Bar theory.

Here they are each presented as showing the NP AP small clause complement in the sentence (highlighted in bold), "I consider

(NP)Mary

(AP)smart":

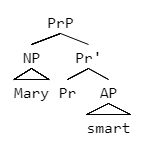

Analysis 1: symmetric constituent

In this analysis, neither of the constituents determine the category, meaning that it is an

exocentric construction. Some linguists believe that the label of this structure can be symmetrically determined by the constituents, and others believe that this structure lacks a label altogether.

[Moro, Andrea. (2008). The anomaly of copular sentences. ''Unpublished manuscript'', ''University of Venice.''] In order to indicate a predicative relationship between the subject (in this case, the NP Mary), and the predicate (AP smart), some have suggested a system of co-indexation, where the subject must

c-command

In generative grammar and related frameworks, a node in a parse tree c-commands its sister node and all of its sister's descendants. In these frameworks, c-command plays a central role in defining and constraining operations such as syntactic movem ...

any predicate associated with it.

This analysis is not compatible with X-bar theory because X-bar theory does not allow for headless constituents, additionally this structure may not be an accurate representation of a small clause because it lacks an intermediate functional element that connects the subject with the predicate. Evidence of this element can be seen as an overt realization in a variety of languages such as Welsh,

Norwegian, and English, as in the examples below

(with the overt predicative functional category highlighted in bold):

#

I regard Fred as insane.

# I consider Fred as my best friend.

Some have taken this as evidence that this structure does not adequately portray the structure of a small clause, and that a better structure must include some intermediate projection that combines the subject and the predicate

which would assign a head to the constituent.

Analysis 2: projection of the predicate

In this analysis, the small clause can be identified as a projection of the

predicate

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, o ...

(in this example, the predicate would be the 'smart' in 'Mary smart'). In this view, the specifier of the structure (in this case, the NP 'Mary') is the subject of the head (in this case, the A 'smart'). This analysis builds on Chomsky's model of phrase structure and is proposed by Stowell and Contreras.

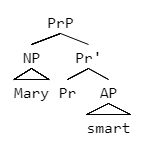

Analysis 3: projection of a functional category

The PrP

[Bowers, J. (1993). The Syntax of Predication. ''Linguistic Inquiry,24''(4), pg. 596-597. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178835] (predicate phrase) category (also analyzed as AgrP,

PredP, and

P

[Balazs, Julie E. (2012). The Syntax of Small Clauses. pg. 23. ''Masters Thesis, Cornell University.'']), was proposed for a few reasons, some of which are outlined below:

* This structure helps to account for

coordination

Coordination may refer to:

* Coordination (linguistics), a compound grammatical construction

* Coordination complex, consisting of a central atom or ion and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions

* Coordination number or ligancy of a cent ...

where the categories of the items being coordinated must be the same. This accounts for the mystery of phrases such as (11) below, where a predicative adjective phrase (AP) is coordinated with a predicative noun phrase (NP), and this coordination of unlike categories is grammatical. The PrP analysis solves this problem by treating the constituents being coordinated as intermediate projection of the Pr head, namely Pr', as in (12).

*#

Mayor Shinn considered Eulalie sub>AP talented and sub>NP a tyrant /li>

*# Mayor Shinn considered sub>PrP Eulalie [Pr' (P) [AP talented and [Pr' (P) [NP a tyrant

* This structure answers the question of the category of the word ''as'' in small clause constructions such as ''I regard Fred as my best friend''. This structure was an issue if ''as'' is analyzed as a preposition, as prepositions do not take adjective phrase complements. However, analyzing ''as'' as the overt realization of the Pr head is consistent with X-bar theory.

# The prisoner seems/appears intelligent.

# The prisoner seems/appears to leave every day at noon.

#

*The prisoner seems/appears leave every day at noon.

Here, examples (13) and (14) show that the subject of an adjectival small clause — with our without copular ''be'' — can raise to the matrix subject position. However, with a verbal clause, omission of infinitival ''to'' leads to ungrammatically, as shown by the contrast between the well-formed (15) and the ill-formed (16), where the asterisk (*) marks ungrammaticality. From this evidence, some linguists have theorized that the subjects of adjectival and verbal small clauses must differ in syntactic position. This conclusion is bolstered by the knowledge that verbal and adjectival small clauses differ in their predication forms. While adjectival small clauses involve

categorical predication where the predicate ascribes a property to the subject, verbal small clauses involve

thetic predicationswhere an event that the subject is participating in is reported.

Basilico uses this to argue that a small clause should be analyzed as a Topic Phrase, which is projected from the predicate head (the Topic), with the subject introduced as the specifier of the Topic Phrase.

In this way, he argues that in an adjectival small clause, the predicate is formed for an individual topic, and in a verbal small clause the events form a predicate of events for a stage topic, which accounts for why verbal small clauses cannot be raised to the matrix subject position.

Identification tests

A small clause divides into two constituents: the subject and its predicate. While small clauses occur cross-linguistically, different languages have different restrictions on what can and cannot be a well-formed (i.e.,

grammatical

In linguistics, grammaticality is determined by the conformity to language usage as derived by the grammar of a particular variety (linguistics), speech variety. The notion of grammaticality rose alongside the theory of generative grammar, the go ...

) small clause. Criteria for identifying a small clause include:

* absence of tense-marking on the predicate

* possibility of negating the small clause predicate

* selectional restrictions imposed by the matrix verb that introduces the small clause

* constituency tests (coordination of small clauses, small clause in subject position, movement of small clause)

Absence of tense-marking

A small clause is characterised as having two constituents NP and XP that enter into a predicative relation, but lacking finite

tense and/or a verb. Possible predicates in small clauses typically include adjective phrases (AP), prepositional phrases (PPs), noun phrases (NPs), or determiner phrases (DPs) (see

determiner phrase In linguistics, a determiner phrase (DP) is a type of phrase headed by a determiner such as ''many''. Controversially, many approaches, take a phrase like ''not very many apples'' to be a DP, headed, in this case, by the determiner ''many''. This ...

page on debate regarding the existence of DPs).

There are two schools of thought regarding NP VP constructions. Some linguists believe that a small clause characteristically lacks a verb, while others believe that a small clause may have a verb but lacks inflected tense. The following examples, which all lack verbs, illustrate small clauses with

P AP

P, or p, is the sixteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''pee'' (pronounced ), plural ''pees''.

History

The ...

(17),

P DP(18), and

P PP(19):

#

''I consider'' ''Mary smart'' /li>

#''I consider'' ''Mary my best friend'' #''I consider'' ''Mary out of her mind''

The small clause examples in (17) to (19) contrast with the examples in (20) to (22), with the critical difference being the inclusion of the copular verb ''be'' preceded by infinitival ''to'':

# *''They think that they are ready left.''

# ''They think that they must leave.''

The asterisk here represents that the sentence (24) is generally held to be ungrammatical by native English speakers.

Selectional restrictions

Selected by matrix verb

Small clauses satisfy selectional requirements of the verb in the main clause in order to be grammatical.

The argument structure of verbs is satisfied with small clause constructions. The following two examples show how the argument structure of the verb "consider" affects what predicate can be in the small clause.

#

''I consider'' ''Mr. Nyman a genius''

# *''I consider ''

''Mr. Nyman in my shed''

Example (18) is ungrammatical as the verb "consider" does take an NP complement, but not a PP complement.

However, this theory of selectional requirement is also disputed, as substitution of different small clauses can create grammatical readings. Both examples (28) and (29) take PP complements, yet (28) is grammatical but (29) is not.

#

''I consider'' ''the team in no fit state to play''

# *''I consider''

''my friends on the roof''

The matrix verb's selection of case also supports the theory that the matrix verb's selectional requirements affect small clause licensing. The verb ''consider'' in (30) marks accusative case on the subject NP of the small clause.

This conclusion is supported by pronoun-substitution, where the accusative caseform is grammatical (31), but the nominative case form is not (32).

#

''I consider'' Natasha a visionary

# ''I consider''

her a visionary

# *''I consider''

she a visionary

In Serbo-Croatian, the verb ''smatrati'' 'to consider' selects for accusative case for its subject argument and instrumental case as its complement argument.

Semantically determined

Small clauses' grammaticality judgments are affected by their semantic value.

The following examples show how semantic selection also affects predication of a small clause.

#

*''The doctor considers'' ''that patient dead tomorrow''

# ''Our pilot considers''

''that island off our route''

Some small clauses that appear to be ungrammatical can be well-formed given the appropriate context. This suggests that the semantic relation of the main verb and the small clause affects sentences' grammaticality.

#

*''I consider'' ''John off my ship''

# ''As soon as he sets foot on the gangplank, I'll consider''

''John off my ship''

Negation

Small clauses may not be negated by a negative modal or auxiliary verb, such as ''don't, shan't'', or ''can't''.

Small clauses may only be negated by negative particles, such as ''not''.

#

''I consider '' ''Rome not a good choice''

# *''I consider''

''Rome might not a good choice''

Constituency

There are a number of considerations that support or refute the one or the other analysis. The layered analysis, which, again, views the small clause as a constituent, is supported by the basic insight that the small clause functions as a single semantic unit, i.e. as a clause consisting of a subject and a predicate.

Coordination

Only constituents of a like type can be joined via coordination. Small clauses can be coordinated, which suggests they are constituents of a like type, but see

coordination (linguistics)

In linguistics, coordination is a complex syntactic structure that links together two or more elements; these elements are called ''conjuncts'' or ''conjoins''. The presence of coordination is often signaled by the appearance of a coordinator (co ...

on the controversy regarding the effectiveness and accuracy of coordination as a constituency test. The following examples illustrate small clause coordination for

P AP

P, or p, is the sixteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''pee'' (pronounced ), plural ''pees''.

History

The ...

(32), and

P NP/DP(33) small clauses.

#

'' He considers'' ''Maria wise'' ''and'' ''Jane talented''

# ''She considers''

''John a tyrant'' ''and''

''Martin a clown''

Subjecthood

The layered analysis is also supported by the fact that in certain cases, a small clause can function as the subject of the greater clause, e.g.

#

''Bill behind the wheel'' ''is a scary thought''. - Small clause functioning as subject

#

''Sam drunk'' ''is something everyone wants to avoid''.

- Small clause functioning as subject

Most theories of syntax judge subjects to be single constituents, hence the small clauses ''Bill behind the wheel'' and ''Sam drunk'' here should each be construed as one constituent. Concerning small clauses in subject position, see Culicover,

Haegeman and Guéron.

Complement of ''with''

Further, small clauses can appear as the complement of ''with'', e.g.:

#

''With'' ''Bill behind the wheel'' ''we're in trouble''. - Small clause as complement of ''with''

# ''With''

''Sam drunk'' ''we've got a big problem''.

- Small clause as complement of ''with''

These data are also easier to accommodate if the small clause is a constituent.

Movement

One could argue, however, that small clauses in subject position and as the complement of ''with'' are fundamentally different from small clauses in object position. Some datapoints have the small clause following the matrix verb, whereby the subject of the small clause is also the object of the matrix clause. In such cases, the matrix verb appears to be

subcategorizing for its object noun (phrase), which then functions as the subject of the small clause. In this regard, there are a number of observations suggesting that the object/subject noun phrase is a direct dependent of the matrix verb. If so, then this means the flat structure is the correct analysis. This captures that fact, with such object/subject noun phrases, as illustrated in (47), the small clause generally does not behave as a single constituent with respect to movement diagnostics. Thus, the "subject" of a small clause cannot participate in topicalization (47b), clefting (47c), pseudo-cleating (47d), nor can it served as an answer fragment (47e). Moreover, like ordinary object NPs, the "subject" of a small clause can becomes the subject of the corresponding passive sentence (47f), and can be realized as a reflexive pronoun that is coindexed with the matrix subject (47g).

The datapoints in (47b-g) are consistent with the flat analysis of small clauses: in such an analysis the object of the matrix clause plays a dual role insofar as it is also the subject of the embedded predicate.

Counter-Arguments

Small clauses' constituency status is not agreed upon by linguists. Some linguists argue that small clauses do not form a constituent, but rather form a noun phrase.

One argument is that

P AP smallclauses cannot occur in the subject position without modification, as shown by the ungrammatically of (48). However, these

P AP

P, or p, is the sixteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''pee'' (pronounced ), plural ''pees''.

History

The ...

small clauses can occur after the verb if they are modified, such as in example (49).

#

* ''Lots of books dirty'' ''is a common problem in libraries''.

#

''Lots of books dirty from mistreatment'' ''is a common problem in libraries''.

A second argument is coordination tests make incorrect predictions about constituency, particularly regarding small clauses. This casts doubt upon the status of small clauses as constituents.

#

Louis gave book to Marie yesterdayand painting to Barbara the day before

Another counterexample of constituency looks at depictive secondary predicates.

#

''They sponged'' ''the water up''

One school of thought argues that this example has

'the water up''behaving as a constituent small clause, while another school of thought argues that the verb "sponge" does not select for a small clause, and that ''the water up'' semantically, but not syntactically, shows the resultative state of the verb.

Cross-linguistic variation

Raising-to-object

Complement small clauses are related to the phenomena of raising-to-object, therefore this theory will be discussed in more detail for English and Korean.

English

Raising-to-object with a direct object is illustrated in (52) with the verb ''proved.'' The bolded constituents represent the small clause of the sentence. By hypothesis, the raising-to-object analysis treats the subject of the small clause as having raised from the embedded small clause to the main clause ''

''

Raising (linguistics)

In linguistics, raising constructions involve the movement of an argument from an embedded or subordinate clause to a matrix or main clause; in other words, a raising predicate/verb appears with a syntactic argument that is not its semantic argum ...

is obligatory in small clauses for the ''make out'' construction.

This is evident by the grammaticality of (i) and ungrammaticality of (ii) without raising-to-object behaviour as demonstrated in the table below:

The range of scope can also implicate the subject of Raising in small clauses.

Semantically, wide scope entails a general situation, for example, ''where everyone has some person that they love'', whereas narrow scope entails a specific situation, for example, ''where everyone love the same person''. Considering only verbless small clauses, small clauses are only accessibly with the wide range of scope with respect to the main verb.

Korean

In Korean, raising-to-object is optional from with complement clauses, but obligatory with complement small clauses. A fully inflected complement clause is given in (55), and the object ''Mary'' can be marked either with nominative case (55a) or with accusative case (55b). In contrast, with a complement small clause as in (56), the subject of the small clause can only be marked with accusative; thus while (56a) is ill-formed, (56b) is well-formed.

Categorical restrictions

French (Romance)

At first glance, French small clauses appear to be unrestricted relative to which category can realize a small clause. Illustrative examples are given below: there are

P AP

P, or p, is the sixteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''pee'' (pronounced ), plural ''pees''.

History

The ...

small clauses (57);

P PPsmall clauses (58), as well as

P VPsmall clauses (59).

However, there are some restrictions on NP VP constructions. The following example (a) is an NP AP small clause construction. The following example (b) is an NP PP small clause construction. The following example (c) is an NP VP small clause construction. The verb here is infinitival, without inflected tense, and takes a PP complement. However, the following example (d) is an NP VP small clause construction that is ungrammatical. Although the verb here is infinitival, it cannot grammatically take an AP complement.

Coordination tests in French do not provide consistent evidence for small clauses' constituency. Below is an example (e) proving small clauses' constituency. The two small clauses in this example use an NP AP construction.

However, the example (f) below makes an incorrect prediction about constituency.

Sportiche provides two possible interpretations of this data: either coordination is not a reliable constituency test or the current theory of constituency should be revised to include strings such as the ones predicted above.

Lithuanian (Balto-Slavic)

Lithuanian small clauses may occur in a NP NP or NP AP construction. NP PP constructions are not small clauses in Lithuanian as the PP does not enter into a predicative relationship with the NP. The example (a) below is of an NP NP construction. The example (b) below is of an NP AP construction. While the English translation of the sentence includes the auxiliary verb "was", it is not present in Lithuanian.

In Lithuanian, small clauses may be moved to the front of the sentence to become the topic. This suggests that the small clause operates as a single unit, or a constituent. Note that the sentence in example (c) in English is ungrammatical so it is marked with an asterisk, but the sentence is grammatical in Lithuanian.

The phrase ''her an immature brat'' cannot be split up in example (d), which provides further evidence that the small clause behaves as a single unit.

Mandarin (Sinitic)

In Mandarin, a small clause does not only lack a verb and tense, but also the presence of functional projections.

The reason for this is that the lexical entries for particular nouns in Mandarin not only contain the categorical feature for nouns, but also for verbs. Thus even with the lack of functional projections, nominals can be predicative in a small clause.

(a) illustrates a complement small clause: it has no tense-marking, only a DP subject and an NP predicate. However, the semantic difference between Mandarin Chinese and English with regards to its small clauses are represented by example (b) and (c). Though (b) is the embedded small clause in the previous example, it cannot be a matrix clause. Despite having the same sentence structure, a small clause consisting of a DP and an NP, due to the ability of a nominal expression to also belong to a second category of verbs, example (c) is a grammatical sentence. This is evidence that there are more restrictive constraints on what is considered a small clause in Mandarin Chinese, which requires further research.

Below is case of special usage of small clause used with the possessive verb ''yǒu''. The small clause is underlined.

Here, the possessive verb ''yǒu'' takes a small clause complement in order to make a degree comparison between the subject and indirect object. Due to the following AP ''gāo'', here the possessive verb ''yǒu'' expresses a limit of the degree of tallness. It is only with a small clause complement that this uncommon degree use of the possessive verb can be communicated.

Variable constituent order

Brazilian Portuguese

In Brazilian Portuguese, there are two types of small clauses: free small clauses and dependent small clauses.

Dependent small clauses are similar to English in that they consist of an NP XP in a predicative relation. Like many other Romance languages, Brazilian Portuguese has free subject-predicate inversion, although it is restricted here to verbs with single arguments. Dependent small clauses may appear in either a standard, as in example (a), or an inverted form, as in example (b).

In contrast, free small clauses cannot occur with subject-predicate order: in example (c), using an

P AP

P, or p, is the sixteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''pee'' (pronounced ), plural ''pees''.

History

The ...

order renders the sentence. Free small clauses only occur in the inverted form: in example (d) the small clause has an

P NPorder, specifically an

P NPorder. The classification of free small clauses is under debate. Some linguists argue that these free small clauses are actually cleft sentences with finite tense,

while other linguists believe that free small clauses are tense phrases without inflected tense on the surface.

Spanish

In Spanish, like many Romance languages, there is some flexibility in small clause construction due to the flexibility in word order. This is posited to be due to the fact that Spanish is an example of a language that is discourse-prominent and agreement-oriented.

[Jiménez-Fernández, Á. L., & Spyropoulos, V. (2013). Feature inheritance, vP phases and the information structure of small clauses. Studia Linguistica, 67(2), 185-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/stul.12013] This passing of features onto the v allows a separation of the object from the verb when the focus of the sentence changes. The final position in a sentence is reserved for the focus as seen by the differences in (a) and (b).

The difference in preference for one construction over the other (

P NPversus

P XP is determined by discourse features.

Refer to the following two examples. In (c) the establish topic is the XP, AP in this case, meaning the information we are seeking is the NP.

Answer

In the following example (e) the reverse is true. We are given the NP in the question and are seeking the information of the XP.

Answer

Notice in (d) and (f) that the English answer remains the same regardless of the question, but in Spanish, one ordering is preferred over the other. When the new information being presented is the XP, the construction preferred is

P XP This is because the sentence-final position is reserved for focus.

It is worth noting that the non-preferred formations (d)(ii) and (f)(i) can be accepted as grammatical if the new information is given the prosodic stress or the established information is destressed, and there is a longer pause between the two constituents, making it right-dislocated.

Greek

Greek is another example of a language that is discourse-prominent and agreement-oriented, allowing features to be passed onto the v.

This allows for flexibility in word order depending on the changing focus of the small clause. This example can be shown in (a) and (b). The construction can either take

P NPor

P XPformations with the focused constituent appearing sentence-finally.

The difference in preference for one construction over the other is determined by discourse features. Newly given information is considered the focus of the sentence and is therefore preferred in sentence-final position. Refer to examples (c) and (e). In (c) the information we are given is the XP (AP in this case) and the information we are seeking is the DP. This means that the preferred construction is

P DP The reverse is true of example (e).

Answer

Answer

It is worth noting that the non-preferred formations (d)(ii) and (f)(i) can be accepted as grammatical if the new information not in sentence-final position is given the emphatic stress.

Expressive exclamatives

English

Expressive Small Clauses, like SCs are verbless and the noun does not carry descriptive content but instead carries expressive content.

[Izumi, Y., & Hayashi, S. (2018). Expressive small clauses in japanese. (pp. 188-199). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93794-6_13] Expressive Small Clauses are evidence that small clauses learned in early development, last until adulthood for language speakers.

[Citko, B. (2011). Small clauses. ''Language and Linguistics Compass,'' 5(10), 748-763. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00312.x] ESCs are illustrated in (a). Expressive small clauses are never used in an argument position of the phrase as seen in (b-i) and do not generally occur within the embedded clause of a sentence as seen in (b-ii).

Both of the examples below are ungrammatical. The bolded constituents are the ESCs.

Unlike ESCs in English, Japanese ESCs differ in two ways:

second person pronouns are not used, and ESCs sometimes appear in argument position.

The example below shows a well-formed ESC in Japanese.

Japanese

The phrase in (a) illustrates the pattern found in Japanese ESCs:

P1''—no—''NP2 (a) illustrates the use of a proximate

demonstrative

Demonstratives ( abbreviated ) are words, such as ''this'' and ''that'', used to indicate which entities are being referred to and to distinguish those entities from others. They are typically deictic; their meaning depending on a particular fram ...

in NP

1 position.

Additionally, first person pronouns, kinship terms, proper names, and other nouns with a

vocative use are able to appear in NP

1 position''—''except for the intermediate

demonstrative

Demonstratives ( abbreviated ) are words, such as ''this'' and ''that'', used to indicate which entities are being referred to and to distinguish those entities from others. They are typically deictic; their meaning depending on a particular fram ...

''so'' (the/that) which is not permitted in ESCs.

While (b) is not ungrammatical, it sounds odd and is uncommonly used.

This is also true of other second person pronouns in Japanese: ''omae'', ''kisama'', and ''temee'' (in progressively impolite forms).

(c) illustrates the use of an ESC in argument position. Notably, ESCs in argument positions lack contextual requirements found in regular ESCs.

Japanese ESCs that are not found in argument position require the addressee to be the same as the noun in NP

1 position.

(c) shows that the addressee of the sentence (Yamada) does not need to be the same as the referent of the ESCs in argument position (Tanaka).

Information structure

English: intonation

Because English is agreement-prominent, there is inflexible SC word order and a heavy importance on intonational focus. Though both answers in English use the same words, focus is given by prosodic stress.

Spanish: word order and intonation

Spanish has a flexible SC word order, and word order determines focus but prosodic stress is able to be used to make non-preferred constructions felicitous.

These examples show the non-felicitous construction but they would be accepted by speakers if the underlined constituents are given emphatic stress and precede a long pause.

See also

*

Balancing and deranking In linguistics, balancing and deranking are terms used to describe the form of verbs used in various types of subordinate clauses and also sometimes in co-ordinate constructions.

* A verb form is said to be balanced if it is identical to forms us ...

*

Constituent

Constituent or constituency may refer to:

Politics

* An individual voter within an electoral district, state, community, or organization

* Advocacy group or constituency

* Constituent assembly

* Constituencies of Namibia

Other meanings

* Consti ...

*

Constituent order

In linguistics, word order (also known as linear order) is the order of the syntactic constituents of a language. Word order typology studies it from a cross-linguistic perspective, and examines how different languages employ different orders. ...

*

Dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of phrase structure) and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesni� ...

*

Exceptional case-marking Exceptional case-marking (ECM), in linguistics, is a phenomenon in which the subject of an embedded infinitival verb seems to appear in a superordinate clause and, if it is a pronoun, is unexpectedly marked with object case morphology (''him'' not ...

*

Information structure

*

Phrase structure grammar

The term phrase structure grammar was originally introduced by Noam Chomsky as the term for grammar studied previously by Emil Post and Axel Thue (Post canonical systems). Some authors, however, reserve the term for more restricted grammars in th ...

*

Raising

*

Subcategorization

References

Literature

*Aarts, B. 1992. Small clauses in English: the non-verbal types. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

*Borsley, R. 1991. Syntactic theory: A unified approach. London: Edward Arnold.

*Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on government and binding: The Pisa lectures. Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter.

*Chomsky, N. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

*Culicover, P. 1997. Principles and parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

*Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

*Haegeman, L. 1994. Introduction to government and binding theory, 2nd edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

*Haegeman, L. and J. Guéron 1999. English grammar: A generative perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

*Matthews, P. 2007. Syntactic relations: A critical survey. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

*Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold.

*Wardhaugh, R. 2003. Understanding English grammar, second edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

{{refend

Clauses

The a-trees on the left are the phrase structure trees, and the b-trees on the right are the dependency trees. The key aspect of these structures is that the small clause material consists of two separate sister constituents.

The flat analysis is preferred by those working in dependency grammars and representational phrase structure grammars (e.g. Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar and

The a-trees on the left are the phrase structure trees, and the b-trees on the right are the dependency trees. The key aspect of these structures is that the small clause material consists of two separate sister constituents.

The flat analysis is preferred by those working in dependency grammars and representational phrase structure grammars (e.g. Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar and  The layered analysis is preferred by those working in the

The layered analysis is preferred by those working in the  In this analysis, neither of the constituents determine the category, meaning that it is an exocentric construction. Some linguists believe that the label of this structure can be symmetrically determined by the constituents, and others believe that this structure lacks a label altogether.Moro, Andrea. (2008). The anomaly of copular sentences. ''Unpublished manuscript'', ''University of Venice.'' In order to indicate a predicative relationship between the subject (in this case, the NP Mary), and the predicate (AP smart), some have suggested a system of co-indexation, where the subject must

In this analysis, neither of the constituents determine the category, meaning that it is an exocentric construction. Some linguists believe that the label of this structure can be symmetrically determined by the constituents, and others believe that this structure lacks a label altogether.Moro, Andrea. (2008). The anomaly of copular sentences. ''Unpublished manuscript'', ''University of Venice.'' In order to indicate a predicative relationship between the subject (in this case, the NP Mary), and the predicate (AP smart), some have suggested a system of co-indexation, where the subject must  In this analysis, the small clause can be identified as a projection of the

In this analysis, the small clause can be identified as a projection of the  The PrPBowers, J. (1993). The Syntax of Predication. ''Linguistic Inquiry,24''(4), pg. 596-597. Retrieved from

The PrPBowers, J. (1993). The Syntax of Predication. ''Linguistic Inquiry,24''(4), pg. 596-597. Retrieved from