sea spider on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sea spiders are marine

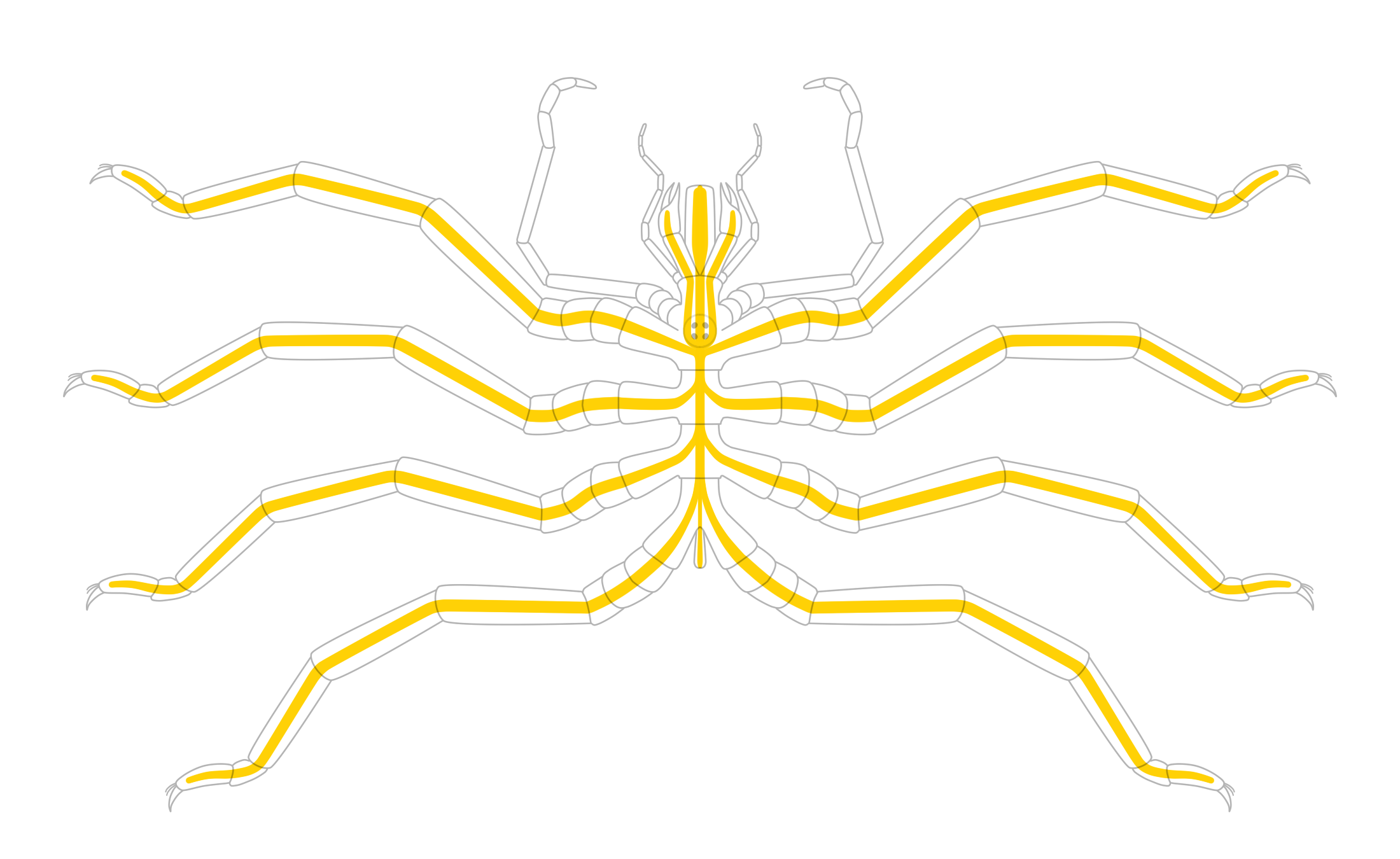

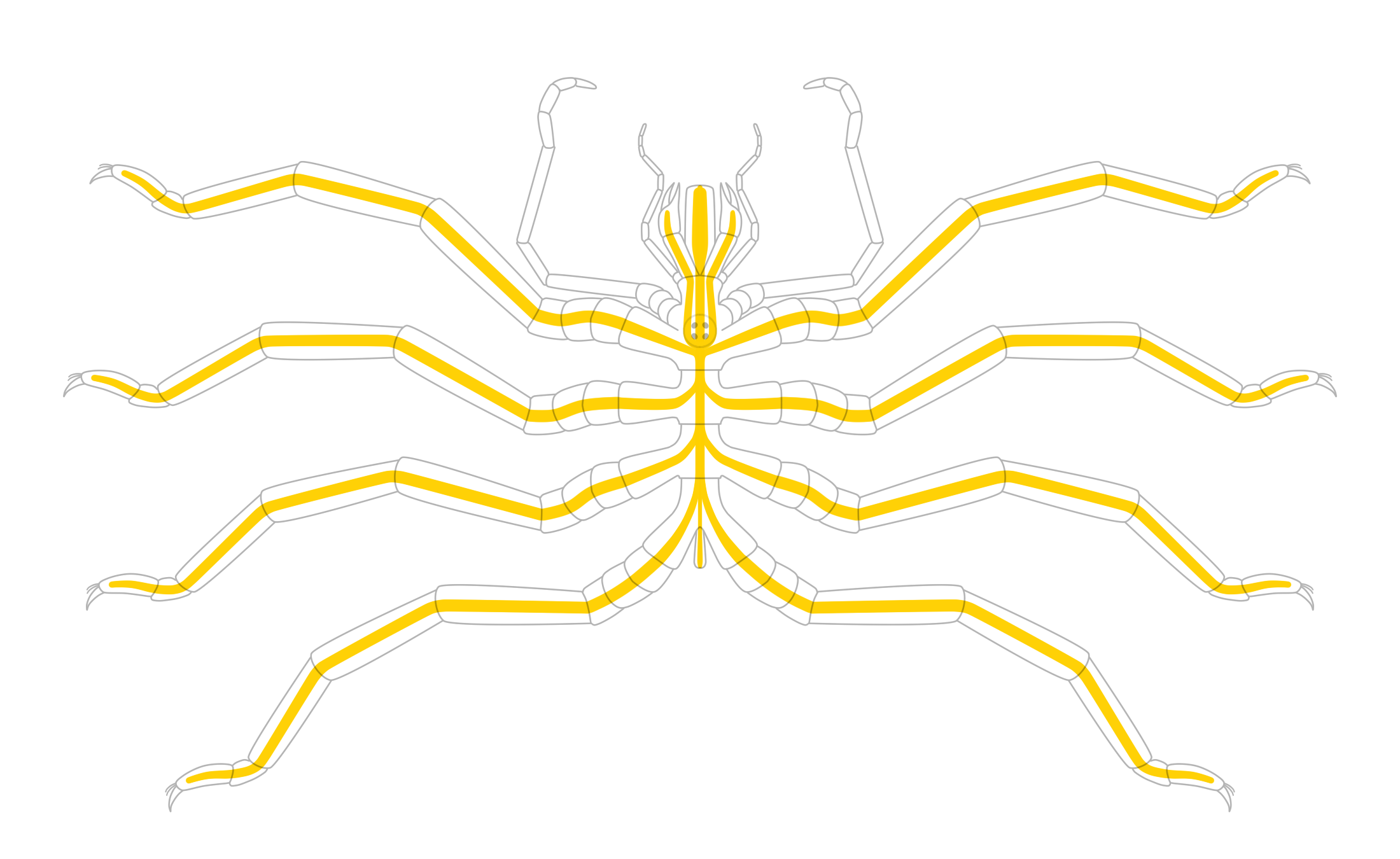

20200205 Pycnogonida Pantopoda morphology.png, Generalized morphology of a pantopod pycnogonid

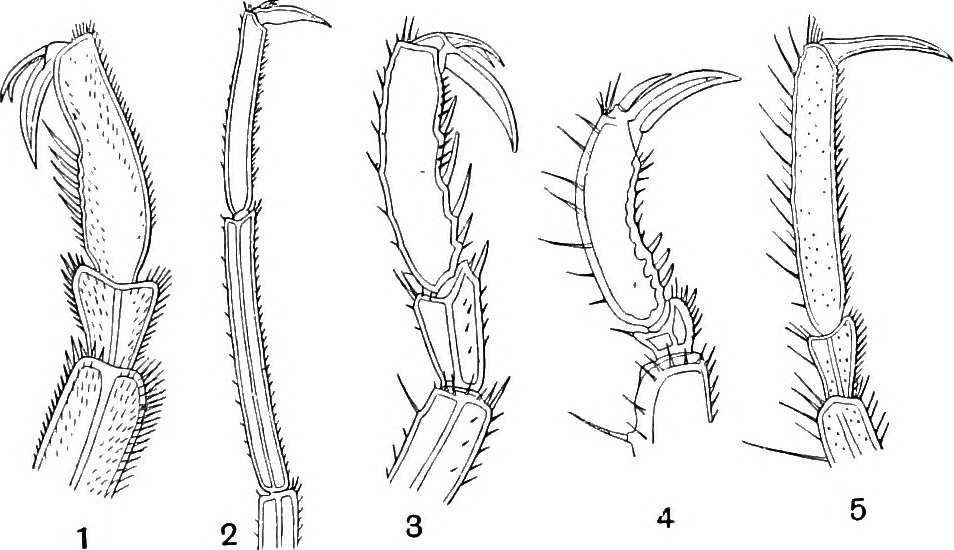

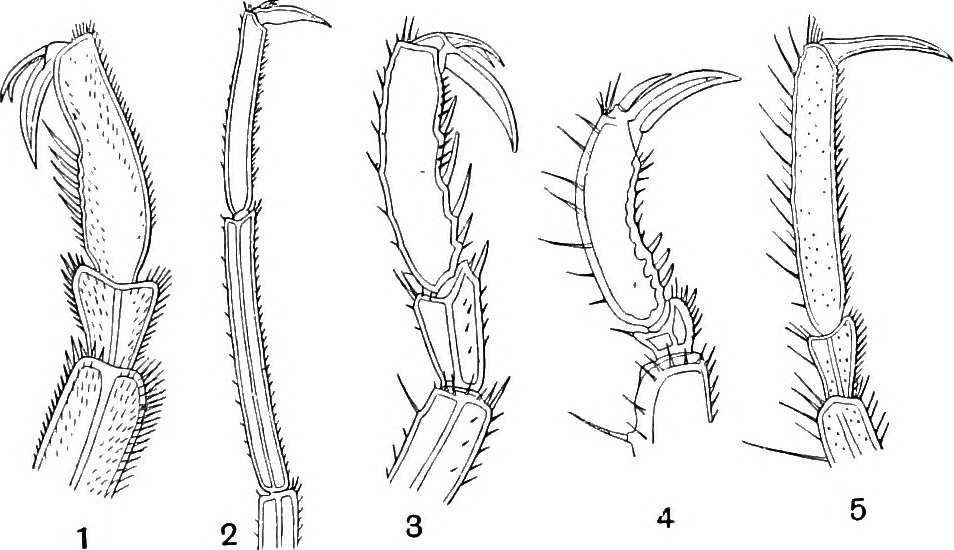

1937 Smithsonian miscellaneous collections Snodgrass 1936 p24 Fig. 07.jpg, Ventral view and leg base of '' Chaetonymphon spinosum''

The cephalon is formed by the fusion of ocular somite and four anterior segments behind it (somite 1–4). It consists of an anterior

Pseudopallene pachycheira.jpeg, '' Pseudopallene pachycheira'', showing robust chelifores and the absence of palps.

Pycnogonum littorale (YPM IZ 030249).jpeg, '' Pycnogonum litorale'', showing the absence of both chelifores and palps. Ovigers are absent in female.

Colossendeis (MNHN-IU-2013-2065).jpeg, '' Colossendeis'' sp., showing the absence of chelifores but otherwise elongated proboscis, palps and ovigers.

Nymphon maculatum 2011-721 (1) (cropped).jpg, '' Nymphon maculatum'', showing the presence of both chelifores, palps and ovigers.

In adult pycnogonids, the chelifores (aka cheliphore), palps and ovigers (aka ovigerous legs) are variably reduced or absent, depending on taxa and sometimes sex. Nymphonidae is the only family where all of three pairs are always functional. The ovigers can be reduced or missing in females, but are present in almost all males. In a functional condition, the chelifores terminate with a

The leg-bearing somites (somite 4 and all trunk somites, the alternatively defined "trunk/thorax") are either segmented or fused to each other, carrying the walking legs via a series of lateral processes (lateral tubular extension of the somites). In most species, the legs are much larger than the body in both length and volume, only being shorter and more slender than the body in Rhynchothoracidae. Each leg is typically composed of eight tubular segments, commonly known as coxa 1, 2 and 3, femur, tibia 1 and 2, tarsus, and propodus. This terminology, with three coxae, no trochanter, and using the term "propodus", is unusual for arthropods. However, based on

The leg-bearing somites (somite 4 and all trunk somites, the alternatively defined "trunk/thorax") are either segmented or fused to each other, carrying the walking legs via a series of lateral processes (lateral tubular extension of the somites). In most species, the legs are much larger than the body in both length and volume, only being shorter and more slender than the body in Rhynchothoracidae. Each leg is typically composed of eight tubular segments, commonly known as coxa 1, 2 and 3, femur, tibia 1 and 2, tarsus, and propodus. This terminology, with three coxae, no trochanter, and using the term "propodus", is unusual for arthropods. However, based on

File:Pycnogonida anatomy - tagged.png, Sagittal section of an ascorhynchid pycnogonid, showing pharynx (F), mid gut (H) and central nervous system (B).

Pycnogonida anatomy tagged.png, Transverse section of a pycnogonid leg, showing gut diverticulum (C, D) and gonad (E)

A striking feature of pycnogonid anatomy is the distribution of their digestive and

Sea spiders live in many different oceanic regions of the world, from

Sea spiders live in many different oceanic regions of the world, from

All sea spiders have separate sexes, except the only known hermaphroditic species ''Ascorhynchus corderoi'' and some extremely rare gynandromorph cases. Among all extant families, Austrodecidae and Rhynchothoracidae are the only two that still lack any observations on their reproductive behaviour and life cycle, as well as Colossendeidae until mid 2020s. Reproduction involves

All sea spiders have separate sexes, except the only known hermaphroditic species ''Ascorhynchus corderoi'' and some extremely rare gynandromorph cases. Among all extant families, Austrodecidae and Rhynchothoracidae are the only two that still lack any observations on their reproductive behaviour and life cycle, as well as Colossendeidae until mid 2020s. Reproduction involves

Since 2010s, the chelicerate affinity of Pycnogonida regain wide support as the sister group of Euchelicerata. Under the basis of phylogenomics, this is one of the only stable topology of chelicerate interrelationships in contrast to the uncertain relationship of many euchelicerate taxa (e.g. poorly resolved position of arachnid orders other than tetrapulmonates and

Since 2010s, the chelicerate affinity of Pycnogonida regain wide support as the sister group of Euchelicerata. Under the basis of phylogenomics, this is one of the only stable topology of chelicerate interrelationships in contrast to the uncertain relationship of many euchelicerate taxa (e.g. poorly resolved position of arachnid orders other than tetrapulmonates and

The

The

World list of PycnogonidaBibliography (compiled by Franz Krapp)

{{Authority control Extant Cambrian first appearances Taxa named by Carl Eduard Adolph Gerstaecker

arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s of the class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after ''Pycnogonum

''Pycnogonum'' is a genus of sea spiders in the family Pycnogonidae. It is the type genus of the family.

Etymology

The generic name (biology), generic name literally means “dense knees”. ''Pycnogonum'' combines the prefix ' (from ‘dense� ...

'', the type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus (''genus typica'') is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearin ...

; with the suffix '). The class includes the only now-living order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Pantopoda ( ‘all feet’), alongside a few fossil species which could trace back to the early or mid Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

. They are cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Internationalism

* World citizen, one who eschews traditional geopolitical divisions derived from national citizenship

* Cosmopolitanism, the idea that all of humanity belongs to a single moral community

* Cosmopolitan ...

, found in oceans around the world. The over 1,300 known species have leg spans ranging from to over . Most are toward the smaller end of this range in relatively shallow depths; however, they can grow to be quite large in Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

and deep waters.

Despite their name and brief resemblance, "sea spiders" are not spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s, nor even arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s. While some literature around the 2000s suggests they may be a sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to all other living arthropods, their traditional classification as a member of chelicerates

The subphylum Chelicerata (from Neo-Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. Chelicerates include the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, tic ...

alongside horseshoe crabs and arachnids has regained wide support in subsequent studies.

Morphology

Many sea spiders are recognised by their enormous walking legs in contrast to a reduced body region, resulting into the so-called "all legs" or "no body" appearance. The body segments (somite

The somites (outdated term: primitive segments) are a set of bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form in the embryogenesis, embryonic stage of somitogenesis, along the head-to-tail axis in segmentation (biology), segmented animals. ...

s) are generally interpreted as three main sections ( tagma): cephalon (head, aka cephalosoma), trunk (aka thorax) and abdomen. However, the definition of cephalon and trunk might differ between literature (see text), and some studies might follow a prosoma (=cephalon+trunk)–opisthosoma (=abdomen) definition, aligning to the tagmosis of other chelicerates. The exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

of the body is tube-like, lacking the dorsoventral division ( tergite and sternite) seen in most other arthropods.

proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a pr ...

, a dorsal ocular tubercle with eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

s, and up to four pairs of appendages

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part or natural prolongation that protrudes from an organism's body such as an arm or a leg. Protrusions from single-celled bacteria and archaea are known as cell-surface appendages or surface app ...

( chelifores, palps, s and first walking legs). Although some literature might consider the segment carrying the first walking leg (somite 4) to be part of the trunk, it is completely fused to the remaining head section to form a single cephalic tagma. The proboscis has three-fold symmetry, terminating with a typically Y-shaped mouth (vertical slit in Austrodecidae). It usually has fairly limited dorsoventral and lateral movement. However, in those species that have reduced chelifores and palps, the proboscis is well developed and flexible, often equipped with numerous sensory bristles and strong rasping ridges around the mouth. The proboscis is unique to pycnogonids, and its exact homology with other arthropod mouthparts is enigmatic, as well as its relationship with the absence of labrum (preoral upper lip of ocular somite) in pycnogonid itself. The ocular tubercle has up to two pairs of simple eyes (ocelli

A simple eye or ocellus (sometimes called a pigment pit) is a form of eye or an optical arrangement which has a single lens without the sort of elaborate retina that occurs in most vertebrates. These eyes are called "simple" to distinguish the ...

) on it, though sometimes the eyes can be reduced or missing, especially among species living in the deep oceans. All of the eyes are median eyes in origin, homologous to the median ocelli of other arthropods, while the lateral eyes (e.g. compound eyes) found in most other arthropods are completely absent.

pincer Pincer may refer to:

*Pincers (tool)

*Pincer (biology), part of an animal

*Pincer ligand, a terdentate, often planar molecule that tightly binds a variety of metal ions

*Pincer (Go), a move in the game of Go

*"Pincers!", an episode of the TV series ...

(chela) formed by two segments (podomeres), like the chelicerae of most other chelicerates. The scape (peduncle) behind the pincer is usually unsegmented, but could be bisegmented in some species, resulting into a total of three or four chelifore segments. The palps and ovigers have up to 9 and 10 segments respectively, but can have fewer even when in a functional condition. The palps are rather featureless and never have claws in adult Pantopoda, while the ovigers may or may not possess a terminal claw and rows of specialised spines on its curved distal segments (strigilis). The chelifores are used for feeding and the palps are used for sensing and manipulating food items, while the ovigers are used for cleaning themselves, with the additional function of carrying offspring in males.

The leg-bearing somites (somite 4 and all trunk somites, the alternatively defined "trunk/thorax") are either segmented or fused to each other, carrying the walking legs via a series of lateral processes (lateral tubular extension of the somites). In most species, the legs are much larger than the body in both length and volume, only being shorter and more slender than the body in Rhynchothoracidae. Each leg is typically composed of eight tubular segments, commonly known as coxa 1, 2 and 3, femur, tibia 1 and 2, tarsus, and propodus. This terminology, with three coxae, no trochanter, and using the term "propodus", is unusual for arthropods. However, based on

The leg-bearing somites (somite 4 and all trunk somites, the alternatively defined "trunk/thorax") are either segmented or fused to each other, carrying the walking legs via a series of lateral processes (lateral tubular extension of the somites). In most species, the legs are much larger than the body in both length and volume, only being shorter and more slender than the body in Rhynchothoracidae. Each leg is typically composed of eight tubular segments, commonly known as coxa 1, 2 and 3, femur, tibia 1 and 2, tarsus, and propodus. This terminology, with three coxae, no trochanter, and using the term "propodus", is unusual for arthropods. However, based on muscular system

The muscular system is an organ (anatomy), organ system consisting of skeletal muscle, skeletal, smooth muscle, smooth, and cardiac muscle, cardiac muscle. It permits movement of the body, maintains posture, and circulates blood throughout the bo ...

and serial homology to the podomeres of other chelicerates, they are most likely coxa (=coxa 1), trochanter (=coxa 2), prefemur/basifemur (=coxa 3), postfemur/telofemur (=femur), patella (=tibia 1), tibia (tibia 2) and two tarsomeres (=tarsus and propodus) in origin. The leg segmentation of Paleozoic taxa is a bit different, noticeably they have annulated coxa 1 and are further divided into two types: one with flattened distal (femur and beyond) segments and first leg pair with one less segment than the other leg pairs (e.g. '' Palaeoisopus'', '' Haliestes''), and another one with an immobile joint between the apparently fourth and fifth segment which altogether might represent a divided femur (e.g. '' Palaeopantopus'', '' Flagellopantopus''). Each leg terminates with a main claw (aka pretarsus/apotele, the true terminal segment), which may or may not have a pair of auxiliary claws on its base. Most of the joints move vertically, except the joint between coxa 1–2 (coxa-trochanter joint) which provide lateral mobility (promotor-remotor motion), and the joint between tarsus and propodus did not have muscles, just like the subdivided tarsus of other arthropods. There are usually eight (four pairs) legs in total, but a few species have five to six pairs. These are known as polymerous (i.e., extra-legged) species, which are distributed among six genera in the families Pycnogonidae (five pairs in '' Pentapycnon''), Colossendeidae (five pairs in '' Decolopoda'' and '' Pentacolossendeis'', six pairs in '' Dodecolopoda'') and Nymphonidae (five pairs in '' Pentanymphon'', six pairs in '' Sexanymphon'').

Several alternatives had been proposed for the position homology of pycnogonid appendages, such as chelifores being protocerebral/homologous to the labrum (see text) or ovigers being duplicated palps. Conclusively, the classic, morphology-based one-by-one alingment to the prosomal appendages of other chelicerates was confirm by both neuroanatomic and genetic evidences. Noticeably, the order of pycnogonid leg pairs are mismatched to those of other chelicerates, starting from the ovigers which are homologous to the first leg pair of arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s. While the fourth walking leg pair was considered aligned to the variably reduced first opisthosomal segment (somite 7, also counted as part of the prosoma based on different studies and/or taxa) of euchelicerates, the origin of the additional fifth and sixth leg pairs in the polymerous species are still enigmatic. Together with the cephalic position of the first walking legs, the anterior and posterior boundary of pycnogonid leg pairs are not aligned to those of euchelicerate prosoma and opisthosoma, nor the cephalon and trunk of pycnogonid itself.

The abdomen (aka trunk end) does not have any appendages. In Pantopoda it is also called the anal tubercle, which is always unsegmented, highly reduced and almost vestigial, simply terminated by the anus

In mammals, invertebrates and most fish, the anus (: anuses or ani; from Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is the external body orifice at the ''exit'' end of the digestive tract (bowel), i.e. the opposite end from the mouth. Its function is to facil ...

. It is considered to be a remnant of opisthosoma/trunk of other chelicerates, but it is unknown which somite (s) it actually aligned to. So far only Paleozoic species have segmented abdomens (at least up to four segments, presumably somite 8–11 which aligned to opisthosomal segment 2–5 of euchelicerates), with some of them even terminated by a long telson

The telson () is the hindmost division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment (biology), segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segm ...

(tail).

Internal anatomy and physiology

reproductive system

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are al ...

s. The pharynx

The pharynx (: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the human mouth, mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs respectively). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates ...

inside the proboscis is lined by dense setae

In biology, setae (; seta ; ) are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Depending partly on their form and function, protostome setae may be called macrotrichia, chaetae ...

, which is possibly related to their feeding behaviour. A pair of gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a Heterocrine gland, mixed gland and sex organ that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gon ...

s (ovaries

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are endocr ...

in female, testes

A testicle or testis ( testes) is the gonad in all male bilaterians, including humans, and is homologous to the ovary in females. Its primary functions are the production of sperm and the secretion of androgens, primarily testosterone.

The ...

in male) is located dorsally in relation to the digestive tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

, but the majority of these organs are branched diverticula throughout the legs because the body is too small to accommodate all of them alone. The midgut diverticula are very long, usually reaching beyond the femur (variably down to tibia 2, tarsus or propodus) of each leg, except in Rhynchothoracidae where they only reach coxa 1. Some species have additional branches (in some ''Pycnogonum

''Pycnogonum'' is a genus of sea spiders in the family Pycnogonidae. It is the type genus of the family.

Etymology

The generic name (biology), generic name literally means “dense knees”. ''Pycnogonum'' combines the prefix ' (from ‘dense� ...

'') or irregular pouches (in '' Endeis'') on the diverticula. There is also a pair of anterior diverticula which corresponds to the chelifores or is inserted into the proboscis in some chelifores-less species. The palps and ovigers never contain diverticula, although some might possess a pair of small diverticula near the bases of these appendages. The gonad diverticula (pedal gonad) reach each femur and open via a gonopore located at coxa 2. The structure and number of the gonopores might differ between sexes (e.g. larger in female, variably absent at the anterior legs of some male). In males, the femur or both femur and tibia 1 possess cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel ( aggregate) together. Cement mi ...

glands.

Pycnogonids do not require a traditional respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

(e.g. gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s). Instead, gasses are absorbed by the legs via the non-calcareous, porous exoskeleton and transferred through the body by diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

. The morphology of pycnogonid creates an efficient surface-area-to-volume ratio

The surface-area-to-volume ratio or surface-to-volume ratio (denoted as SA:V, SA/V, or sa/vol) is the ratio between surface area and volume of an object or collection of objects.

SA:V is an important concept in science and engineering. It is use ...

for respiration to occur through direct diffusion. Oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

is absorbed by the legs and is transported via the hemolymph to the rest of the body with an open circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart a ...

. The small, long, thin pycnogonid heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

beats vigorously at 90 to 180 beats per minute, creating substantial blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of Circulatory system, circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term ...

. The beating of the heart drives circulation in the trunk and in the part of the legs closest to the trunk, but is not important for the circulation in the rest of the legs. Hemolymph circulation in the legs is mostly driven by the peristaltic movement of the gut diverticula that extend into every leg, a process called gut peristalsis. In the case of taxa without a heart (e.g. Pycnogonidae), the whole circulatory system is presumed to be solely maintained by gut peristalsis.

The central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

of pycnogonid largely retains a segmented ladder-like structure. It consists of a dorsal brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

( supraesophageal ganglion) and a pair of ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous system. It is the functional equivalent of the vertebrate spinal cord. The ventral nerve cord coordinates neural signaling from the brain to the body and vice ve ...

s, intercepted by the esophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus (Œ, archaic spelling) (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), c ...

. The former is a fusion of the first and second brain segments (cerebral ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

)—protocererum and deutocerebrum—corresponding to the eyes/ocular somite and chelifores/somite 1 respectively. The whole section was rotated during pycnogonid evolution, as the protocerebrum went upward and the deutocerebrum shifted forward. The third commissure is established inferior to the esophagus. This third brain segment, or tritocerebrum (corresponding to the palps/somite 2), is fused to the oviger/somite 3 ganglia instead, which is followed up by the final ovigeral somata in the protonymphon larva of '' Pycnogonum litorale''. A series of leg ganglia (somite 4 and so on) develop as molts progress, with incorporation of the first leg ganglia into the subesophageal ganglia in certain taxa. The leg ganglia might shift anteriorly or even cluster together, but are never highly fused into the ring-like synganglion of other chelicerates. The abdominal ganglia are vestigal, absorbed by the preceding leg ganglia during juvenile development.

Distribution and ecology

Sea spiders live in many different oceanic regions of the world, from

Sea spiders live in many different oceanic regions of the world, from Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, and the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

coast of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

, to the north and south poles. They are most common in shallow waters, but can be found as deep as , and live in both marine and estuarine habitats. Pycnogonids are well camouflaged beneath the rocks and among the algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

that are found along shorelines.

Sea spiders are benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

in general, using their stilt-like legs to walk along the bottom, but they are also capable of swimming by using an umbrella pulsing motion, and some Paleozoic species with flatten legs might even have a nektonic lifestyle. Sea spiders are mostly carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s or scavenger

Scavengers are animals that consume Corpse decomposition, dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a he ...

s that feed on soft-bodied invertebrates such as cnidarian

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

s, sponges

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and ar ...

, polychaete

Polychaeta () is a paraphyletic class of generally marine Annelid, annelid worms, common name, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes (). Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called c ...

s, and bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary Colony (biology), colonies. Typically about long, they have a spe ...

ns, by inserting their proboscis into targeted prey item. Although they are known to feed on sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

s, most sea anemones survive this ordeal, making the sea spider a parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

rather than a predator of sea anemones. A few species such as '' Nymphonella tapetis'' are specialised endoparasites of bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

mollusk

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The ...

s.

Not much is known about the primary predators of sea spiders, if any. At least some species have obvious defensive methods such as amputating and regenerating body parts, or being unpleasant meals via high levels of ecdysteroids (ecdysis hormone

A hormone (from the Ancient Greek, Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of cell signaling, signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs or tissues by complex biological processes to regulate physio ...

). On the other hand, sea spiders are known to be infected by parasitic gastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

mollusks or hitch‐rided by sessile animals such as goose barnacle

Goose barnacles, also called percebes, turtle-claw barnacles, stalked barnacles, gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles form ...

s, which may negatively affect their locomotion and respiratory efficiency.

Reproduction and development

All sea spiders have separate sexes, except the only known hermaphroditic species ''Ascorhynchus corderoi'' and some extremely rare gynandromorph cases. Among all extant families, Austrodecidae and Rhynchothoracidae are the only two that still lack any observations on their reproductive behaviour and life cycle, as well as Colossendeidae until mid 2020s. Reproduction involves

All sea spiders have separate sexes, except the only known hermaphroditic species ''Ascorhynchus corderoi'' and some extremely rare gynandromorph cases. Among all extant families, Austrodecidae and Rhynchothoracidae are the only two that still lack any observations on their reproductive behaviour and life cycle, as well as Colossendeidae until mid 2020s. Reproduction involves external fertilisation

External fertilization is a mode of reproduction in which a male organism's sperm fertilizes a female organism's egg outside of the female's body.

It is contrasted with internal fertilization, in which sperm are introduced via insemination and then ...

when male and female stack together (usually male on top), exuding sperm and eggs from the gonopores of their respective leg coxae. After fertilisation, males glue the egg cluster with cement glands and using their ovigers (the oviger-lacking '' Nulloviger'' using only the ventral body wall) to carry the laid eggs and young. Colossendeidae is the only known exception that the egg mass was placed on substrate and well-camouflaged.

In most cases, the offsprings hatch as a distinct larval stage known as protonymphon. It has a blind gut and the body consists of a cephalon and its first three pairs of cephalic appendages only: the chelifores, palps and ovigers. In this stage, the chelifores usually have attachment glands, while the palps and ovigers are subequal, three-segmented appendages known as palpal and ovigeral larval limbs. When the larvae moult

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is a process by which an animal casts off parts of its body to serve some beneficial purpose, either at ...

into the postlarval stage, they undergo transitional metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and different ...

: the leg-bearing segments develop and the three pairs of cephalic appendages further develop or reduce. The postlarva eventually metamorphoses into a juvenile that looks like a miniature adult, which will continue to moult into an adult with a fixed number of walking legs. In Pycnogonidae, the ovigers are reduced in juveniles but reappear in oviger-bearing adult males.

These kind of "head-only" larvae and its anamorphic

Anamorphic format is a cinematography technique that captures widescreen images using recording media with narrower native Aspect ratio (image), aspect ratios. Originally developed for 35 mm movie film, 35 mm film to create widescreen pres ...

metamorphosis resemble crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

nauplius larvae and megacheiran larvae, all together might reflects how the larvae of a common ancestor of all arthropods developed: starting its life as a tiny animal with a few head appendages, while new body segments and appendages were gradually added as it was growing.

Further details of the postembryonic developments of sea spiders vary, but their categorization might differ between literatures. As of the 2010s, there are five types identified as follows:

The type 1 (typical protonymphon) is the most common and possibly an ancestral one. When the type 2 and 5 (attaching larva) hatches it immediately attaches itself to the ovigers of the father, where it will stay until it has turned into a small and young juvenile with two or three pairs of walking legs ready for a free-living existence. The type 3 (atypical protonymphon) have limited observations. The adults are free living, while the larvae and the juveniles are living on or inside temporary hosts such as polychaete

Polychaeta () is a paraphyletic class of generally marine Annelid, annelid worms, common name, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes (). Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called c ...

s and clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve mollusc. The word is often applied only to those that are deemed edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the sea floor or riverbeds. Clams h ...

s. The type 4 (encysted larva) is a parasite that hatches from the egg and finds a host in the shape of a polyp colony where it burrows into and turns into a cyst, and will not leave the host before it has turned into a young juvenile.

Taxonomy

Phylogenetic position

Sea spiders had been interpreted as some kind ofarachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s or crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s in historical studies. However, after the concept of Chelicerata

The subphylum Chelicerata (from Neo-Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. Chelicerates include the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, tic ...

being established in 20th century, sea spiders have long been considered part of the subphylum, alongside euchelicerate taxa such as Xiphosura (horseshoe crabs) and Arachnida (spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s, scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s, mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

s, tick

Ticks are parasitic arachnids of the order Ixodida. They are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, and species, but can become larger when engorged. Ticks a ...

s, harvestmen

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an Order (biology), order of arachnids,

Common name, colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs (see below). , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered w ...

and other lesser-known orders).

A competing hypothesis around 2000s proposes that Pycnogonida belong to their own lineage, sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to ref ...

to the lineage lead to other extant arthropods (i.e. euchelicerates, myriapod

Myriapods () are the members of subphylum Myriapoda, containing arthropods such as millipedes and centipedes. The group contains about 13,000 species, all of them terrestrial.

Although molecular evidence and similar fossils suggests a diversifi ...

s, crustaceans and hexapods, collectively known as Cormogonida). This Cormogonida hypothesis was first indicated by early phylogenomic analysis aroud that time, followed by another study suggest that the sea spider's chelifores are not positionally homologous to the chelicerae of euchelicerates (originated from the deutocerebral segment/somite 1), as was previously supposed. Instead, the chelifore nerves were thought to be innervated by the protocerebrum

The protocerebrum is the first segment of the supraoesophageal ganglion, panarthropod brain.

Recent studies suggest that it comprises two regions.

Region associated with the expression of ''six3''

''six3'' is a transcription factor that marks ...

, the first segment of the arthropod brain which corresponded to the ocular somite, bearing the eyes

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

and labrum. This condition of having paired protocerebral appendages is not found anywhere else among arthropods, except in other panarthropods such as onychophora

Onychophora (from , , "claws"; and , , "to carry"), commonly known as velvet worms (for their velvety texture and somewhat wormlike appearance) or more ambiguously as peripatus (after the first described genus, ''Peripatus''), is a phylum of el ...

n (primary antennae) and contestably in Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

stem-group arthropods like radiodonts (frontal appendages), which was taken as evidence that Pycnogonida may be basal than all other living arthropods, since the protocerebral appendages were thought to be reduced and fused into a labrum in the last common ancestor of crown-group arthropods, and pycnogonids did not have a labrum coexist with the chelifores. If that's true, it would have meant the sea spiders are the last surviving (and highly modified) members of an ancient, basal arthropods that originated in Cambrian oceans. However, the basis of this hypothesis was immediately refuted by subsequent studies using Hox gene

Hox genes, a subset of homeobox, homeobox genes, are a gene cluster, group of related genes that Evolutionary developmental biology, specify regions of the body plan of an embryo along the craniocaudal axis, head-tail axis of animals. Hox protein ...

expression patterns, demonstrated the developmental homology between chelicerae and chelifores, with chelifore nerves innervated by a deuterocerebrum that has been rotated forwards, which was misinterpreted as protocerebrum by the aforementioned study.

Since 2010s, the chelicerate affinity of Pycnogonida regain wide support as the sister group of Euchelicerata. Under the basis of phylogenomics, this is one of the only stable topology of chelicerate interrelationships in contrast to the uncertain relationship of many euchelicerate taxa (e.g. poorly resolved position of arachnid orders other than tetrapulmonates and

Since 2010s, the chelicerate affinity of Pycnogonida regain wide support as the sister group of Euchelicerata. Under the basis of phylogenomics, this is one of the only stable topology of chelicerate interrelationships in contrast to the uncertain relationship of many euchelicerate taxa (e.g. poorly resolved position of arachnid orders other than tetrapulmonates and scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s; non-monophyly of Arachnida in respect to Xiphosura). This is consistent with the chelifore-chelicera homology, as well as other morphological similarities and differences between pycnogonids and euchelicerates. However, due to pycnogonid's highly modified anatomy and lack of intermediate fossils, their evolutional origin and relationship with the basal fossil chelicerates (such as habeliids and '' Mollisonia'') are still difficult to compare and interpret.

Interrelationship

The class Pycnogonida comprises over 1,300species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, which are split into over 80 genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

. All extant genera are considered part of the single order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Pantopoda, which was subdivided into 11 families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

. Historically there are only 9 families, with species of nowadays Ascorhynchidae placed under Ammotheidae and Pallenopsidae under Callipallenidae. Both were eventually separated after they are considered distinct from the once-belonged families.

Phylogenomic analysis of extant sea spiders was able to establish a backbone tree for Pantopoda, revealing some consistent relationship such as the basal position of Austrodecidae, monophyly

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent comm ...

of some major branches (later redefined as superfamilies) and the paraphyly

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

of Callipallenidae in respect to Nymphonidae. The topology also suggest Pantopoda undergoing multiple times of cephalic appendage reduction/reappearance and polymerous species acquisition, contray to previous hypothesis on pantopod evolution (cephalic appendages were thought to be progressively reduced along the branches, and polymerus condition were though to be ancestral). On the other hand, the position of Ascorhynchidae and '' Nymphonella'' are less certain across multiple results.

The position of Paleozoic pycnogonids are poorly examined, but most, if not, all of them most likely represent members of stem-group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

basal than Pantopoda (crown-group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

Pycnogonida), especially those with segmented abdomen, a feature that was most likely ancestral and reduce in the Pantopoda lineage. While some phylogenetic analysis placing them within Pantopoda, this result is questionable as they have low support values and based on outdated interpretation of the fossil taxa.

According to the World Register of Marine Species

The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) is a taxonomic database that aims to provide an authoritative and comprehensive catalogue and list of names of marine organisms.

Content

The content of the registry is edited and maintained by scien ...

, the Class Pycnogonida is subdivided as follows (with subsequent updates on fossil taxa after Sabroux et al. (2023, 2024)):

*Genus †'' Cambropycnogon'' Waloszek & Dunlop, 2002

*Genus †'' Flagellopantopus'' Poschmann & Dunlop, 2005 (classified under Pantopoda ''incertae sedis'' by WoRMS)

*Genus †'' Haliestes'' Siveter et al., 2004 (previously classified under Order Nectopantpoda Bamber, 2007 and Family Haliestidae Bamber, 2007)

*Genus †'' Palaeoisopus'' Broili, 1928 (Previously classified under Order Palaeoisopoda Hedgpeth, 1978 and Family Palaeoisopodidae Dubinin, 1957)

*Genus †'' Palaeomarachne'' Rudkin et al., 2013

*Genus †'' Palaeopantopus'' Broili, 1929 (Previously classified under Order Palaeopantopoda Broili, 1930 and Family Palaeopantopodidae Hedgpeth, 1955)

* Genus †'' Palaeothea'' Bergstrom, Sturmer & Winter, 1980 (previously classified under Pantopoda, potential ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

'')

* Genus †'' Pentapantopus'' Kühl, Poschmann & Rust, 2013 (previously classified under Pantopoda)

*Order Pantopoda Gerstäcker, 1863

**Suborder Eupantopodida Fry, 1978

***Superfamily Ammotheoidea Dohrn, 1881

****Family Ammotheidae Dohrn, 1881

****Family Pallenopsidae Fry, 1978

***Superfamily Ascorhynchoidea Pocock, 1904

****Family Ascorhynchidae Hoek, 1881 (=Eurycydidae Sars, 1891)

***Superfamily Colossendeoidea Hoek, 1881 (=Pycnogonoidea Pocock, 1904; Rhynchothoracoidea Fry, 1978)

****Family Colossendeidae Jarzynsky, 1870

****Family Pycnogonidae Wilson, 1878

****Family Rhynchothoracidae Thompson, 1909

***Superfamily Nymphonoidea Pocock, 1904

****Family Callipallenidae Hilton, 1942

****Family Nymphonidae Wilson, 1878

***Superfamily Phoxichilidioidea Sars, 1891

****Family Endeidae Norman, 1908

****Family Phoxichilidiidae Sars, 1891

**Suborder Stiripasterida

Austrodecidae is a family (biology), family of sea spiders. Austrodecids tend to be small measuring only 1–2 mm, characterized by an annulated proboscis with vertical slit-like mouth opening. It is the most basal family of the order Pantop ...

Fry, 1978

***Family Austrodecidae Stock, 1954

**Suborder ''incertae sedis''

*** Family † Palaeopycnogonididae Sabroux, Edgecombe, Pisani & Garwood, 2023

***Genus '' Alcynous'' Costa, 1861 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Foxichilus'' Costa, 1836 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Oiceobathys'' Hesse, 1867 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Oomerus'' Hesse, 1874 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Paritoca'' Philippi, 1842 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Pephredro'' Goodsir, 1842 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Phanodemus'' Costa, 1836 (nomen dubium)

***Genus '' Platychelus'' Costa, 1861 (nomen dubium)

Fossil record

The

The fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

record of pycnogonids is scant, represented only by a handful of fossil sites with exceptional preservation (Lagerstätte

A Fossil-Lagerstätte (, from ''Lager'' 'storage, lair' '' Stätte'' 'place'; plural ''Lagerstätten'') is a sedimentary deposit that preserves an exceptionally high amount of palaeontological information. ''Konzentrat-Lagerstätten'' preserv ...

). While most of them are discovered from Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

era, unambiguous evidence of crown-group (Pantopoda) only restricted to Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

era.

The earliest fossils are '' Cambropycnogon'' discovered from the Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

' Orsten' of Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

( ca. 500 Ma). So far only its protonymphon larvae had been described, featuring some traits unknown from other pycnogonids such as paired anterior projections, gnathobasic larval limbs and annulated terminal appendages. Due to its distinct morphology, some studies have argued that this genus is not a pycnogonid at all.

Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon (geology), Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years f ...

pycnogonids are only known by '' Palaeomarachne'' (ca. 450 Ma), a genus found in William Lake Provincial Park, Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

and described in 2013. It only preserve possible moults of the fragmental body segments, with one showing an apparently segmented head region.

However, just like ''Cambropycnogon'', its pycnogonid affinity was questioned by some studies as well.

The Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

Coalbrookdale Formation of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

('' Haliestes'', ca. 425 Ma) and the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

Hunsrück Slate of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

('' Flagellopantopus'', '' Palaeopantopus'', '' Palaeoisopus'', '' Palaeothea'' and '' Pentapantopus'', ca. 400 Ma) include unambigious fossil pycnogonids with exceptional preservation. The latter is by far the most diverse community of fossil pycnogonids in terms of both species number and morphology. Some of them are significant in that they possess something never seen in pantopods: annulated coxae, flatten swimming legs, segmented abdomen and elongated telson. These provide some clues on the evolution of sea spider bodyplan before the arose and diversification of Pantopoda.

Fossil of Mesozoic pycnogonids are even rare, and so far all of them are Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

pantopods. Historically there are two genus ('' Pentapalaeopycnon'' and '' Pycnogonites'') from the Solnhofen Limestone (ca. 150 Ma) of Germany being described as such, which are in fact misidentified phyllosoma larvae of decapod

The Decapoda or decapods, from Ancient Greek δεκάς (''dekás''), meaning "ten", and πούς (''poús''), meaning "foot", is a large order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, and includes crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and p ...

crustaceans. The actual first report of Mesozoic pycnogonids was described by researchers from the University of Lyon in 2007, discovering 3 new genus ('' Palaeopycnogonides'', '' Colossopantopodus'' and '' Palaeoendeis'') from La Voulte-sur-Rhône of Jurassic La Voulte Lagerstätte (ca. 160 Ma), south-east France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. The discovery fill in an enormous fossil gap in the record between Devonian and extant sea spiders. In 2019, a new species of ''Colossopantopodus'' and a specimen possibly belong to the extant genus '' Eurycyde'' were discovered from the aforementioned Solnhofen limestone.

References

External links

* *PycnoBaseWorld list of Pycnogonida

{{Authority control Extant Cambrian first appearances Taxa named by Carl Eduard Adolph Gerstaecker