protozoan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

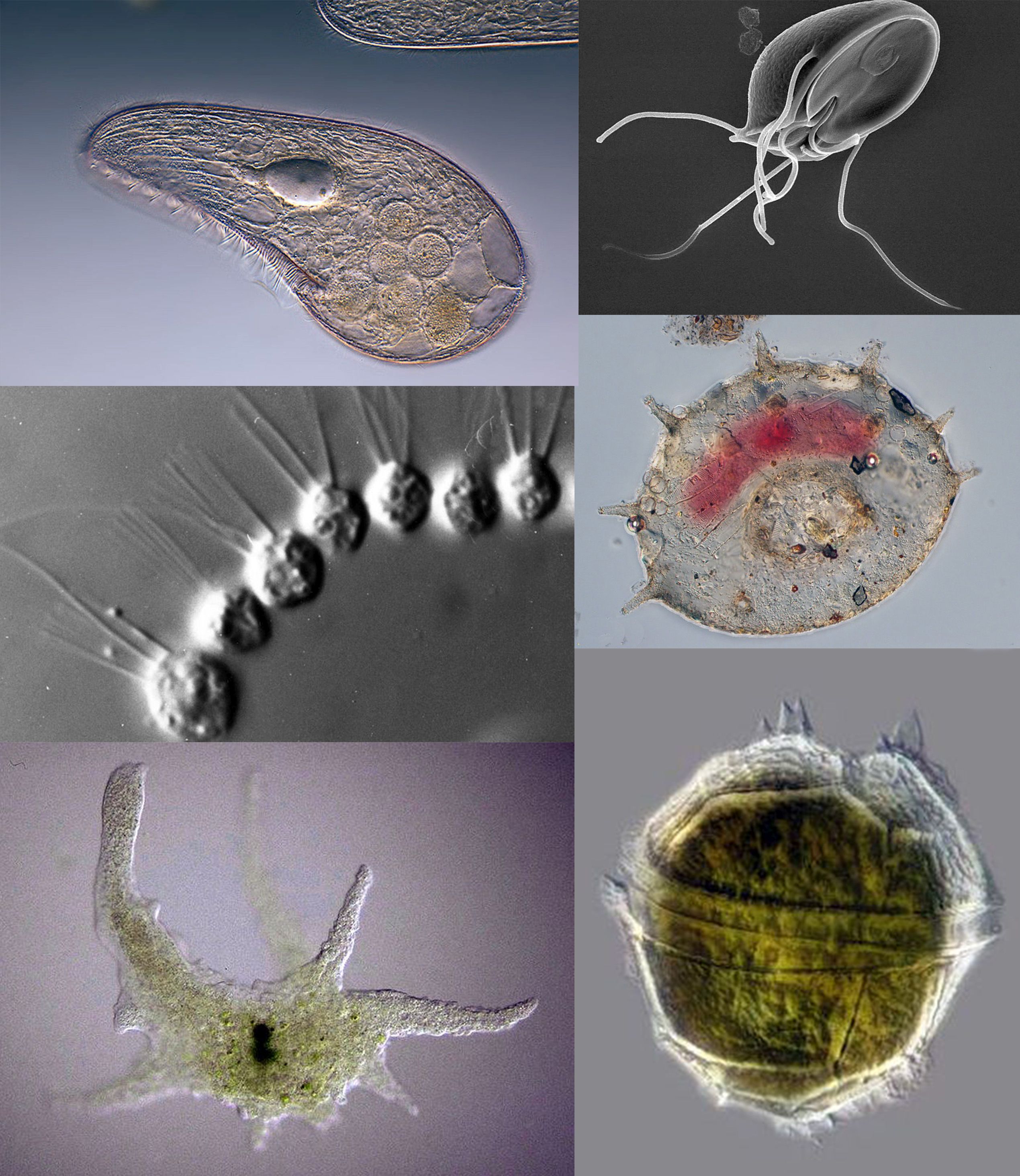

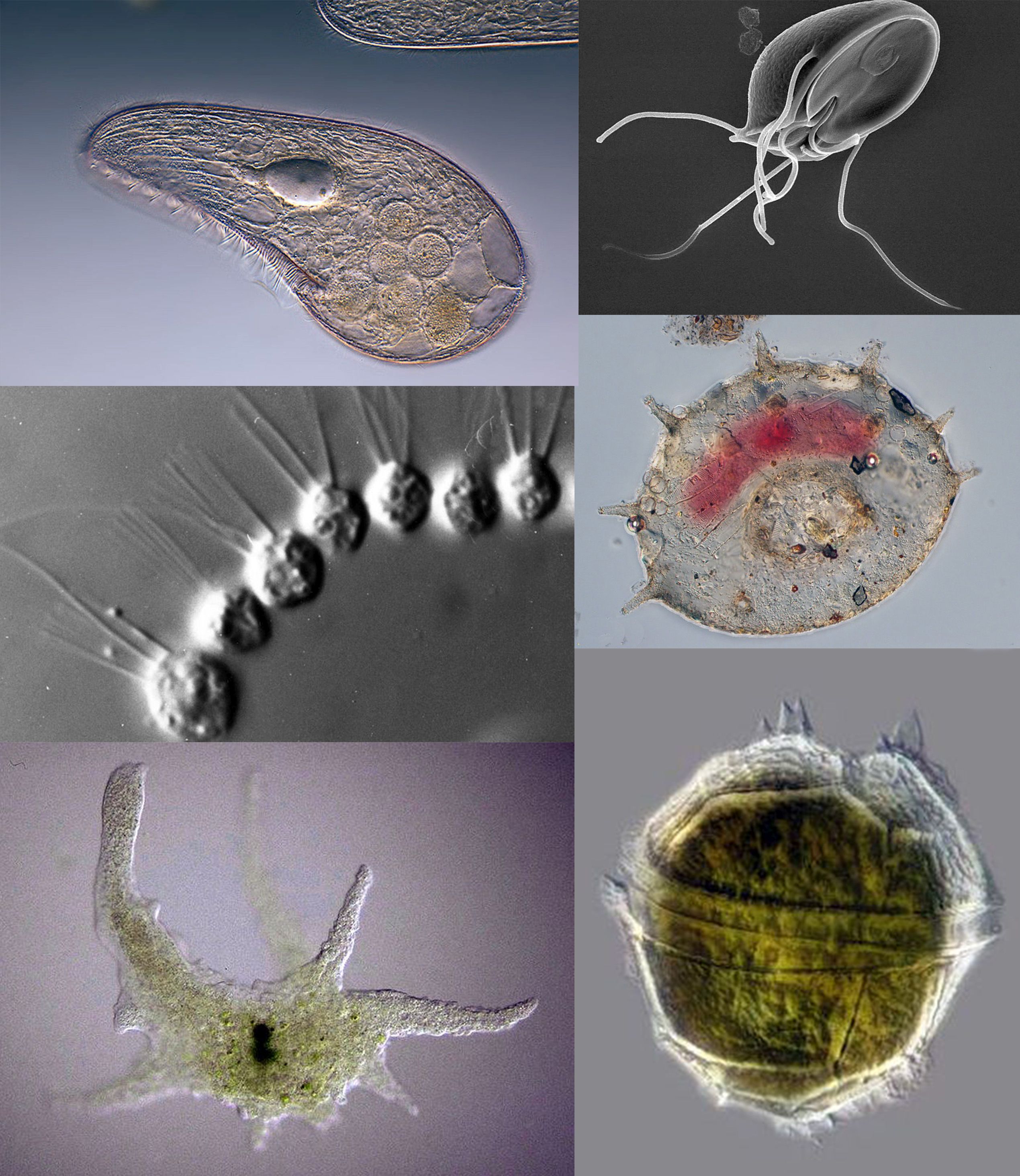

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled

The word "protozoa" ''(singular ''protozoon'')'' was coined in 1818 by zoologist Georg August Goldfuss (=Goldfuß), as the Greek equivalent of the German ', meaning "primitive, or original animals" (' ‘proto-’ + ' ‘animal’). Goldfuss created Protozoa as a

The word "protozoa" ''(singular ''protozoon'')'' was coined in 1818 by zoologist Georg August Goldfuss (=Goldfuß), as the Greek equivalent of the German ', meaning "primitive, or original animals" (' ‘proto-’ + ' ‘animal’). Goldfuss created Protozoa as a  As a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in a simplistic "two-kingdom" concept of life, according to which all living beings were classified as either animals or plants. As long as this scheme remained dominant, the protozoa were understood to be animals and studied in departments of Zoology, while photosynthetic microorganisms and microscopic fungi—the so-called Protophyta—were assigned to the Plants, and studied in departments of Botany.

Criticism of this system began in the latter half of the 19th century, with the realization that many organisms met the criteria for inclusion among both plants and animals. For example, the algae '' Euglena'' and '' Dinobryon'' have

As a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in a simplistic "two-kingdom" concept of life, according to which all living beings were classified as either animals or plants. As long as this scheme remained dominant, the protozoa were understood to be animals and studied in departments of Zoology, while photosynthetic microorganisms and microscopic fungi—the so-called Protophyta—were assigned to the Plants, and studied in departments of Botany.

Criticism of this system began in the latter half of the 19th century, with the realization that many organisms met the criteria for inclusion among both plants and animals. For example, the algae '' Euglena'' and '' Dinobryon'' have

Association between protozoan symbionts and their host organisms can be mutually beneficial. Flagellated protozoa such as ''

Association between protozoan symbionts and their host organisms can be mutually beneficial. Flagellated protozoa such as ''

Protozoa may also live as mixotrophs, combining a heterotrophic diet with some form of autotrophy. Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zoochlorellae), which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and provide nutrients to the host. The algae are not digested, but reproduce and are distributed between division products. The organism may benefit at times by deriving some of its nutrients from the algal endosymbionts or by surviving anoxic conditions because of the oxygen produced by algal photosynthesis. Some protozoans practice kleptoplasty, stealing

Protozoa may also live as mixotrophs, combining a heterotrophic diet with some form of autotrophy. Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zoochlorellae), which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and provide nutrients to the host. The algae are not digested, but reproduce and are distributed between division products. The organism may benefit at times by deriving some of its nutrients from the algal endosymbionts or by surviving anoxic conditions because of the oxygen produced by algal photosynthesis. Some protozoans practice kleptoplasty, stealing

Some protozoa have two-phase life cycles, alternating between proliferative stages (e.g., trophozoites) and resting

Some protozoa have two-phase life cycles, alternating between proliferative stages (e.g., trophozoites) and resting

A number of protozoan

A number of protozoan

''Electron-Microscopic Structure of Protozoa''

Pergamon Press, Oxford. ; Physiology and biochemistry * Nisbet, B. 1984. ''Nutrition and feeding strategies in Protozoa.'' Croom Helm Publ., London, 280 pp. * Coombs, G.H. & North, M. 1991. ''Biochemical protozoology''. Taylor & Francis, London, Washington. * Laybourn-Parry J. 1984. ''A Functional Biology of Free-Living Protozoa''. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. * Levandowski, M., S.H. Hutner (eds). 1979. ''Biochemistry and physiology of protozoa''. Volumes 1, 2, and 3. Academic Press: New York, NY; 2nd ed. * Sukhareva-Buell, N.N. 2003. ''Biologically active substances of protozoa''. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ; Ecology * Capriulo, G.M. (ed.). 1990. ''Ecology of Marine Protozoa.'' Oxford Univ. Press, New York. * Darbyshire, J.F. (ed.). 1994. ''Soil Protozoa.'' CAB International: Wallingford, U.K. 2009 pp. * Laybourn-Parry, J. 1992. ''Protozoan plankton ecology.'' Chapman & Hall, New York. 213 pp. * Fenchel, T. 1987. ''Ecology of protozoan: The biology of free-living phagotrophic protists.'' Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 197 pp. ; Parasitology * Kreier, J.P. (ed.). 1991–1995. ''Parasitic Protozoa'', 2nd ed. 10 vols (1-3 coedited by Baker, J.R.). Academic Press, San Diego, California

; Methods * Lee, J. J., & Soldo, A. T. (1992). ''Protocols in protozoology''. Kansas, USA: Society of Protozoologists, Lawrence

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

s, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in old ...

s or organic tissues and debris. Historically, protozoans were regarded as "one-celled animals", because they often possess animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage ...

-like behaviours, such as motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

and predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

, and lack a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

, as found in plants and many algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

.

When first introduced by Georg Goldfuss (originally spelled Goldfuß) in 1818, the taxon Protozoa was erected as a class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

within the Animalia, with the word 'protozoa' meaning "first animals". In later classification schemes it was elevated to a variety of higher ranks, including phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature ...

, subkingdom and kingdom, and sometimes included within Protoctista or Protista

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

. The approach of classifying Protozoa within the context of Animalia was widespread in the 19th and early 20th century, but not universal. By the 1970s, it became usual to require that all taxa be monophyletic (derived from a common ancestor that would also be regarded as protozoan), and holophyletic (containing all of the known descendants of that common ancestor). The taxon 'Protozoa' fails to meet these standards, and the practices of grouping protozoa with animals, and treating them as closely related, are no longer justifiable. The term continues to be used in a loose way to describe single-celled protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

s (that is, eukaryotes that are not animals, plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s, or fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

) that feed by heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

y. Some examples of protozoa are '' Amoeba'', '' Paramecium'', '' Euglena'' and '' Trypanosoma''.

Despite awareness that the traditional taxonomic concept of "Protozoa" did not meet contemporary taxonomic standards, some authors have continued to use the name, while applying it to differing scopes of organisms. In a series of classifications by Thomas Cavalier-Smith

Thomas (Tom) Cavalier-Smith, FRS, FRSC, NERC Professorial Fellow (21 October 1942 – 19 March 2021), was a professor of evolutionary biology in the Department of Zoology, at the University of Oxford.

His research has led to discov ...

and collaborators since 1981, the taxon Protozoa was applied to a restricted circumscription of organisms, and ranked as a kingdom. A scheme presented by Ruggiero et al. in 2015, places eight not closely related phyla within Kingdom Protozoa: Euglenozoa, Amoebozoa, Metamonada, Choanozoa

Choanozoa is a clade of opisthokont eukaryotes consisting of the choanoflagellates (Choanoflagellatea) and the animals (Animalia, Metazoa). The sister-group relationship between the choanoflagellates and animals has important implications for th ...

''sensu'' Cavalier-Smith, Loukozoa, Percolozoa, Microsporidia

Microsporidia are a group of spore-forming unicellular parasites. These spores contain an extrusion apparatus that has a coiled polar tube ending in an anchoring disc at the apical part of the spore. They were once considered protozoans or pr ...

and Sulcozoa. Notably, this approach excludes several major groups of organisms traditionally placed among the protozoa, including the ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s, dinoflagellates, foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

, and the parasitic apicomplexans, which were located in other groups such as Alveolata and Stramenopiles, under the polyphyletic Chromista. The Protozoa in this scheme do not form a monophyletic and holophyletic group (clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

), but a paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

group or evolutionary grade, because it excludes some descendants of Protozoa, as used in this sense.

Science

The word "protozoa" ''(singular ''protozoon'')'' was coined in 1818 by zoologist Georg August Goldfuss (=Goldfuß), as the Greek equivalent of the German ', meaning "primitive, or original animals" (' ‘proto-’ + ' ‘animal’). Goldfuss created Protozoa as a

The word "protozoa" ''(singular ''protozoon'')'' was coined in 1818 by zoologist Georg August Goldfuss (=Goldfuß), as the Greek equivalent of the German ', meaning "primitive, or original animals" (' ‘proto-’ + ' ‘animal’). Goldfuss created Protozoa as a class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

containing what he believed to be the simplest animals. From p. 1008: ''"Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa."'' (First class. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) ote: each column of each page of this journal is numbered; there are two columns per page./ref> Originally, the group included not only single-celled microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in old ...

s but also some "lower" multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially ...

animals, such as rotifer

The rotifers (, from the Latin , "wheel", and , "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John H ...

s, coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

s, sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throu ...

s, jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbre ...

, bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about long, they have a special feeding structure called a ...

and polychaete worms. The term ''Protozoa'' is formed from the Greek words (), meaning "first", and (), plural of (), meaning "animal". The use of Protozoa as a formal taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

has been discouraged by some researchers, mainly because the term implies kinship with animals (Metazoa) and promotes an arbitrary separation of "animal-like" from "plant-like" organisms.

In 1848, as a result of advancements in the design and construction of microscopes and the emergence of a cell theory pioneered by Theodor Schwann and Matthias Schleiden, the anatomist and zoologist C. T. von Siebold proposed that the bodies of protozoa such as ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s and amoebae consisted of single cells, similar to those from which the multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially ...

tissues of plants and animals were constructed. Von Siebold redefined Protozoa to include only such unicellular forms, to the exclusion of all metazoa

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage in ...

(animals). At the same time, he raised the group to the level of a phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature ...

containing two broad classes of microorganisms: Infusoria (mostly ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s) and flagellate

A flagellate is a cell or organism with one or more whip-like appendages called flagella. The word ''flagellate'' also describes a particular construction (or level of organization) characteristic of many prokaryotes and eukaryotes and thei ...

s (flagellated protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

s) and amoebae ( amoeboid organisms). The definition of Protozoa as a phylum or sub-kingdom composed of "unicellular animals" was adopted by the zoologist Otto Bütschli

Johann Adam Otto Bütschli (3 May 1848 – 2 February 1920) was a German zoologist and professor at the University of Heidelberg. He specialized in invertebrates and insect development. Many of the groups of protists were first recognized by him ...

—celebrated at his centenary as the "architect of protozoology". With its increasing visibility, the term 'protozoa' and the discipline of 'protozoology' came into wide use.

As a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in a simplistic "two-kingdom" concept of life, according to which all living beings were classified as either animals or plants. As long as this scheme remained dominant, the protozoa were understood to be animals and studied in departments of Zoology, while photosynthetic microorganisms and microscopic fungi—the so-called Protophyta—were assigned to the Plants, and studied in departments of Botany.

Criticism of this system began in the latter half of the 19th century, with the realization that many organisms met the criteria for inclusion among both plants and animals. For example, the algae '' Euglena'' and '' Dinobryon'' have

As a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in a simplistic "two-kingdom" concept of life, according to which all living beings were classified as either animals or plants. As long as this scheme remained dominant, the protozoa were understood to be animals and studied in departments of Zoology, while photosynthetic microorganisms and microscopic fungi—the so-called Protophyta—were assigned to the Plants, and studied in departments of Botany.

Criticism of this system began in the latter half of the 19th century, with the realization that many organisms met the criteria for inclusion among both plants and animals. For example, the algae '' Euglena'' and '' Dinobryon'' have chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

s for photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

, like plants, but can also feed on organic matter and are motile, like animals. In 1860, John Hogg

John Joseph Hogg (born 19 March 1949) is a former Australian politician who served as a Senator for Queensland from 1996 to 2014, representing the Labor Party. He served as President of the Senate from 2008 to 2014.

Early life

Hogg was bor ...

argued against the use of "protozoa", on the grounds that "naturalists are divided in opinion — and probably some will ever continue so—whether many of these organisms or living beings, are animals or plants." As an alternative, he proposed a new kingdom called Primigenum, consisting of both the protozoa and unicellular algae, which he combined under the name "Protoctista". In Hoggs's conception, the animal and plant kingdoms were likened to two great "pyramids" blending at their bases in the Kingdom Primigenum.

Six years later, Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new s ...

also proposed a third kingdom of life, which he named Protista

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

. At first, Haeckel included a few multicellular organisms in this kingdom, but in later work, he restricted the Protista to single-celled organisms, or simple colonies whose individual cells are not differentiated into different kinds of tissues.

Despite these proposals, Protozoa emerged as the preferred taxonomic placement for heterotrophic microorganisms such as amoebae and ciliates, and remained so for more than a century. In the course of the 20th century, the old "two kingdom" system began to weaken, with the growing awareness that fungi did not belong among the plants, and that most of the unicellular protozoa were no more closely related to the animals than they were to the plants. By mid-century, some biologists, such as Herbert Copeland, Robert H. Whittaker and Lynn Margulis, advocated the revival of Haeckel's Protista or Hogg's Protoctista as a kingdom-level eukaryotic group, alongside Plants, Animals and Fungi. A variety of multi-kingdom systems were proposed, and the Kingdoms Protista and Protoctista became established in biology texts and curricula.

While most taxonomists have abandoned Protozoa as a high-level group, Cavalier-Smith used the term with a different circumscription. In 2015, Protozoa ''sensu'' Cavalier-Smith excluded several major groups of organisms traditionally placed among the protozoa (such as ciliates, dinoflagellates and foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

). This and similar concepts of Protozoa are of a paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

group which does not include all organisms that descended from Protozoa. In this case, the most significant absences were of the animals and fungi. The continued use by some of the 'Protozoa' in its old sense highlights the uncertainty as to what is meant by the word 'Protozoa', the need for disambiguating statements (here, the term 'Protozoa' is used in the sense intended by Goldfuß), and the problems that arise when new meanings are given to familiar taxonomic terms.

Some authors classify Protozoa as a subgroup of mostly motile Protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

s. Others class any unicellular eukaryotic microorganism as a Protist, and make no reference to 'Protozoa'.

In 2005, members of the Society of Protozoologists voted to change its name to the International Society of Protistologists.

Characteristics

Reproduction

Reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual or ...

in Protozoa can be sexual or asexual. Most Protozoa reproduce asexually through binary fission.

Many parasitic Protozoa reproduce both asexually and sexually. However, sexual reproduction is rare among free-living protozoa and it usually occurs when food is scarce or the environment changes drastically. Both isogamy

Isogamy is a form of sexual reproduction that involves gametes of the same morphology (indistinguishable in shape and size), found in most unicellular eukaryotes. Because both gametes look alike, they generally cannot be classified as male or ...

and anisogamy

Different forms of anisogamy: A) anisogamy of motile cells, B) egg_cell.html"_;"title="oogamy_(egg_cell">oogamy_(egg_cell_and_sperm_cell),_C)_anisogamy_of_non-motile_cells_(egg_cell_and_spermatia)..html" ;"title="egg_cell_and_sperm_cell.html" ;" ...

occur in Protozoa with anisogamy being the more common form of sexual reproduction.

Size

Protozoa, as traditionally defined, range in size from as little as 1micrometre

The micrometre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American and British English spelling differences# ...

to several millimetre

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the metre and its derived scales. The microwave is between 1 meter to 1 millimeter.

The millimetre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, ...

s, or more. Among the largest are the deep-sea–dwelling xenophyophores

Xenophyophorea is a clade of foraminiferans. Members of this class are multinucleate unicellular organisms found on the ocean floor throughout the world's oceans, at depths of . They are a kind of foraminiferan that extract minerals from the ...

, single-celled foraminifera whose shells can reach 20 cm in diameter.

Habitat

Free-living protozoa are common and often abundant in fresh, brackish and salt water, as well as other moist environments, such as soils and mosses. Some species thrive in extreme environments such as hot springs and hypersaline lakes and lagoons. All protozoa require a moist habitat; however, some can survive for long periods of time in dry environments, by forming resting cysts that enable them to remain dormant until conditions improve. Parasitic andsymbiotic

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or para ...

protozoa live on or within other organisms, including vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with ...

s and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s, as well as plants and other single-celled organisms. Some are harmless or beneficial to their host organisms; others may be significant causes of diseases, such as babesia

''Babesia'', also called ''Nuttallia'', is an apicomplexan parasite that infects red blood cells and is transmitted by ticks. Originally discovered by the Romanian bacteriologist Victor Babeș in 1888, over 100 species of ''Babesia'' have since ...

, malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

and toxoplasmosis.

Association between protozoan symbionts and their host organisms can be mutually beneficial. Flagellated protozoa such as ''

Association between protozoan symbionts and their host organisms can be mutually beneficial. Flagellated protozoa such as ''Trichonympha

''Trichonympha'' is a genus of single-celled, anaerobic parabasalids of the order Hypermastigia that is found exclusively in the hindgut of lower termites and wood roaches. ''Trichonympha''’s bell shape and thousands of flagella make it an eas ...

'' and ''Pyrsonympha

''Pyrsonympha'' is a genus of Excavata

Excavata is a major supergroup of unicellular organisms belonging to the domain Eukaryota. It was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999 and introduced by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002 as a for ...

'' inhabit the guts of termites, where they enable their insect host to digest wood by helping to break down complex sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

s into smaller, more easily digested molecules. A wide range of protozoa live commensally in the rumens of ruminant animals, such as cattle and sheep. These include flagellates, such as ''Trichomonas

''Trichomonas'' is a genus of anaerobic excavate parasites of vertebrates. It was first discovered by Alfred François Donné in 1836 when he found these parasites in the pus of a patient suffering from vaginitis, an inflammation of the vagina ...

'', and ciliated protozoa, such as '' Isotricha'' and '' Entodinium''. The ciliate subclass Astomatia is composed entirely of mouthless symbionts adapted for life in the guts of annelid worms.

Feeding

All protozoa areheterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

ic, deriving nutrients from other organisms, either by ingesting them whole by phagocytosis or taking up dissolved organic matter or micro-particles ( osmotrophy). Phagocytosis may involve engulfing organic particles with pseudopodia

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (plural: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filament ...

(as amoebae do), taking in food through a specialized mouth-like aperture called a cytostome

A cytostome (from ''cyto-'', cell and ''stome-'', mouth) or cell mouth is a part of a cell specialized for phagocytosis, usually in the form of a microtubule-supported funnel or groove. Food is directed into the cytostome, and sealed into vacuole ...

, or using stiffened ingestion organellesFenchel, T. 1987. Ecology of protozoan: The biology of free-living phagotrophic protists. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Parasitic protozoa use a wide variety of feeding strategies, and some may change methods of feeding in different phases of their life cycle. For instance, the malaria parasite ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ve ...

'' feeds by pinocytosis during its immature trophozoite stage of life (ring phase), but develops a dedicated feeding organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' th ...

(cytostome) as it matures within a host's red blood cell.

Protozoa may also live as mixotrophs, combining a heterotrophic diet with some form of autotrophy. Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zoochlorellae), which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and provide nutrients to the host. The algae are not digested, but reproduce and are distributed between division products. The organism may benefit at times by deriving some of its nutrients from the algal endosymbionts or by surviving anoxic conditions because of the oxygen produced by algal photosynthesis. Some protozoans practice kleptoplasty, stealing

Protozoa may also live as mixotrophs, combining a heterotrophic diet with some form of autotrophy. Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zoochlorellae), which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and provide nutrients to the host. The algae are not digested, but reproduce and are distributed between division products. The organism may benefit at times by deriving some of its nutrients from the algal endosymbionts or by surviving anoxic conditions because of the oxygen produced by algal photosynthesis. Some protozoans practice kleptoplasty, stealing chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

s from prey organisms and maintaining them within their own cell bodies as they continue to produce nutrients through photosynthesis. The ciliate '' Mesodinium rubrum'' retains functioning plastids from the cryptophyte algae on which it feeds, using them to nourish themselves by autotrophy. The symbionts may be passed along to dinoflagellates of the genus '' Dinophysis'', which prey on ''Mesodinium rubrum'' but keep the enslaved plastids for themselves. Within ''Dinophysis'', these plastids can continue to function for months.

Motility

Organisms traditionally classified as protozoa are abundant in aqueous environments andsoil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

, occupying a range of trophic levels. The group includes flagellate

A flagellate is a cell or organism with one or more whip-like appendages called flagella. The word ''flagellate'' also describes a particular construction (or level of organization) characteristic of many prokaryotes and eukaryotes and thei ...

s (which move with the help of undulating and beating flagella). Ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s (which move by using hair-like structures called cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proje ...

) and amoebae (which move by the use of temporary extensions of cytoplasm called pseudopodia

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (plural: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filament ...

). Many protozoa, such as the agents of amoebic meningitis, use both pseudopodia and flagella. Some protozoa attach to the substrate or form cysts so they do not move around ( sessile). Most sessile protozoa are able to move around at some stage in the life cycle, such as after cell division. The term 'theront' has been used for actively motile phases, as opposed to 'trophont' or 'trophozoite' that refers to feeding stages.

Walls, pellicles, scales, and skeletons

Unlike plants, fungi and most types of algae, most protozoa do not have a rigid externalcell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

, but are usually enveloped by elastic structures of membranes that permit movement of the cell. In some protozoa, such as the ciliates and euglenozoans, the outer membrane of the cell is supported by a cytoskeletal infrastructure, which may be referred to as a "pellicle". The pellicle gives shape to the cell, especially during locomotion. Pellicles of protozoan organisms vary from flexible and elastic to fairly rigid. In ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s and Apicomplexa, the pellicle includes a layer of closely packed vesicles called alveoli. In euglenids, the pellicle is formed from protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

strips arranged spirally along the length of the body. Familiar examples of protists with a pellicle are the euglenoids

Euglenids (euglenoids, or euglenophytes, formally Euglenida/Euglenoida, ICZN, or Euglenophyceae, ICBN) are one of the best-known groups of flagellates, which are excavate eukaryotes of the phylum Euglenophyta and their cell structure is typical ...

and the ciliate '' Paramecium''. In some protozoa, the pellicle hosts epibiotic

An epibiont (from the Ancient Greek meaning "living on top of") is an organism that lives on the surface of another living organism, called the basibiont ("living underneath"). The interaction between the two organisms is called epibiosis. An e ...

bacteria that adhere to the surface by their fimbriae (attachment pili).

Life cycle

cysts

A cyst is a closed sac, having a distinct envelope and division compared with the nearby tissue. Hence, it is a cluster of cells that have grouped together to form a sac (like the manner in which water molecules group together to form a bubble) ...

. As cysts, some protozoa can survive harsh conditions, such as exposure to extreme temperatures or harmful chemicals, or long periods without access to nutrients, water, or oxygen. Encysting enables parasitic species to survive outside of a host, and allows their transmission from one host to another. When protozoa are in the form of trophozoites (Greek ''tropho'' = to nourish), they actively feed. The conversion of a trophozoite to cyst form is known as encystation, while the process of transforming back into a trophozoite is known as excystment.

Protozoa mostly reproduce asexually by binary fission or multiple fission. Many protozoa also exchange genetic material by sexual means (typically, through conjugation

Conjugation or conjugate may refer to:

Linguistics

*Grammatical conjugation, the modification of a verb from its basic form

* Emotive conjugation or Russell's conjugation, the use of loaded language

Mathematics

*Complex conjugation, the change ...

), but this is generally decoupled from the process of reproduction, and does not immediately result in increased population. Thus, sexuality can be optional.

Although meiotic sex is widespread among present day eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

s, it has, until recently, been unclear whether or not eukaryotes were sexual early in their evolution. Owing to recent advances in gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

detection and other techniques, evidence has been found for some form of meiotic sex in an increasing number of protozoa of lineages that diverged early in eukaryotic evolution. (See eukaryote reproduction.) Such findings suggest that meiotic sex arose early in eukaryotic evolution. Examples of protozoan meiotic sexuality are described in the articles '' Amoebozoa'', '' Giardia lamblia'', ''Leishmania

''Leishmania'' is a parasitic protozoan, a single-celled organism of the genus '' Leishmania'' that are responsible for the disease leishmaniasis. They are spread by sandflies of the genus ''Phlebotomus'' in the Old World, and of the genus ' ...

'', '' Plasmodium falciparum biology'', '' Paramecium'', '' Toxoplasma gondii'', ''Trichomonas vaginalis

''Trichomonas vaginalis'' is an anaerobic, flagellated protozoan parasite and the causative agent of a sexually transmitted disease called trichomoniasis. It is the most common pathogenic protozoan that infects humans in industrialized countri ...

'' and '' Trypanosoma brucei''.

Classification

Historically, Protozoa were classified as "unicellular animals", as distinct from the Protophyta, single-celled photosynthetic organisms (algae), which were considered primitive plants. Both groups were commonly given the rank of phylum, under the kingdom Protista. In older systems of classification, the phylum Protozoa was commonly divided into several sub-groups, reflecting the means of locomotion. Classification schemes differed, but throughout much of the 20th century the major groups of Protozoa included: *Flagellate

A flagellate is a cell or organism with one or more whip-like appendages called flagella. The word ''flagellate'' also describes a particular construction (or level of organization) characteristic of many prokaryotes and eukaryotes and thei ...

s, or Mastigophora (motile cells equipped with whiplike organelles of locomotion, e.g., '' Giardia lamblia'')

* Amoebae or Sarcodina (cells that move by extending pseudopodia

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (plural: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filament ...

or lamellipodia

The lamellipodium (plural lamellipodia) (from Latin ''lamella'', related to ', "thin sheet", and the Greek radical ''pod-'', "foot") is a cytoskeletal protein actin projection on the leading edge of the cell. It contains a quasi-two-dimensiona ...

, e.g., '' Entamoeba histolytica'')

* Sporozoa, or Apicomplexa or Sporozoans (parasitic, spore-producing cells, whose adult form lacks organs of motility, e.g., '' Plasmodium knowlesi'')

** Apicomplexa (now in Alveolata)

** Microsporidia

Microsporidia are a group of spore-forming unicellular parasites. These spores contain an extrusion apparatus that has a coiled polar tube ending in an anchoring disc at the apical part of the spore. They were once considered protozoans or pr ...

(now in Fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

)

** Ascetosporea (now in Rhizaria)

** Myxosporidia (now in Cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that ...

)

* Ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s, or Ciliophora (cells equipped with large numbers of cilia used for movement and feeding, e.g. ''Balantidium coli

''Balantidium coli'' is a parasitic species of ciliate alveolates that causes the disease balantidiasis. It is the only member of the ciliate phylum known to be pathogenic to humans.

Morphology

''Balantidium coli'' has two developmental stag ...

'')

With the emergence of molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

and tools enabling researchers to directly compare the DNA of different organisms, it became evident that, of the main sub-groups of Protozoa, only the ciliates (Ciliophora) formed a natural group, or monophyletic clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

, once a few extraneous members (such as ''Stephanopogon'' or protociliates and opalinids) were removed. The Mastigophora, Sarcodina, and Sporozoa were polyphyletic groups. The similarities of appearance and ways of life by which these groups were defined had emerged independently in their members by convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

.

In most systems of eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

classification, such as one published by the International Society of Protistologists, members of the old phylum Protozoa have been distributed among a variety of supergroups.

Ecology

Free-living protozoa are found in almost all ecosystems that contain, at least some of the time, free water. They have a critical role in the mobilization of nutrients in natural ecosystems. Their role is best conceived within the context of themicrobial food web The microbial food web refers to the combined trophic interactions among microbes in aquatic environments. These microbes include viruses, bacteria, algae, heterotrophic protists (such as ciliates and flagellates).Mostajir B, Amblard C, Buffan-Duba ...

in which they include the most important bacterivores. In part, they facilitate the transfer of bacterial and algal production to successive trophic levels, but also they solubilize the nutrients within microbial biomass, allowing stimulation of microbial growth. As consumers, protozoa prey upon unicellular or filamentous algae, bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, microfungi, and micro-carrion. In the context of older ecological models of the micro- and meiofauna, protozoa may be a food source for microinvertebrates.

That most species of free-living protozoa have been found in similar habitats in all parts of the globe is an observation that dates back to the 19th Century (e.g. Schewiakoff). In the 1930s, Lourens Baas Becking

Lourens Gerhard Marinus Baas Becking (4 January 1895 in Deventer – 6 January 1963 in Canberra, Australia) was a Dutch botanist and microbiologist. He is known for the Baas Becking hypothesis, which he originally formulated as ''"Everything ...

asserted "Everything is everywhere, but the environment selects". This has been restated and explained, especially by Tom Fenchel and Bland Findlay and methodically explored and affirmed at least in respect of morphospecies of free-living flagellates. The widespread distribution of microbial is explained by the ready dispersal of physically small organisms. While Baas Becking's hypothesis is not universally accepted, the natural microbial world is undersampled, and this will favour conclusions of endemism.

Disease

pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a g ...

s are human parasite

Human parasites include various protozoa and worms.

Human parasites are divided into endoparasites, which cause infection inside the body, and ectoparasites, which cause infection superficially within the skin.

The cysts and eggs of endoparasit ...

s, causing diseases such as malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

(by ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ve ...

''), amoebiasis, giardiasis, toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis, sometimes informally called crypto, is a parasitic disease caused by '' Cryptosporidium'', a genus of protozoan parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa. It affects the distal small intestine and can affect the respiratory tra ...

, trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis (trich) is an infectious disease caused by the parasite ''Trichomonas vaginalis''. About 70% of affected people do not have symptoms when infected. When symptoms occur, they typically begin 5 to 28 days after exposure. Symptoms ca ...

, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a wide array of clinical manifestations caused by parasites of the trypanosome genus '' Leishmania''. It is generally spread through the bite of phlebotomine sandflies, ''Phlebotomus'' and ''Lutzomyia'', and occurs most freq ...

, African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), ''Acanthamoeba'' keratitis, and primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (naegleriasis).

Protozoa include the agents of the most significant entrenched infectious diseases, particularly malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, and, historically, sleeping sickness.

The protozoon ''Ophryocystis elektroscirrha

''Ophryocystis elektroscirrha'' (sometimes abbreviated OE or ''O.e.'') is an obligate, neogregarine protozoan parasite that infects monarch (''Danaus plexippus'') and queen (''Danaus gilippus'') butterflies. There are no other known hosts. The ...

'' is a parasite of butterfly

Butterflies are insects in the macrolepidopteran clade Rhopalocera from the order Lepidoptera, which also includes moths. Adult butterflies have large, often brightly coloured wings, and conspicuous, fluttering flight. The group compris ...

larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

e, passed from female to caterpillar. Severely infected individuals are weak, unable to expand their wings, or unable to eclose, and have shortened lifespans, but parasite levels vary in populations. Infection creates a culling

In biology, culling is the process of segregating organisms from a group according to desired or undesired characteristics. In animal breeding, it is the process of removing or segregating animals from a breeding stock based on a specific tr ...

effect, whereby infected migrating animals are less likely to complete the migration. This results in populations with lower parasite loads at the end of the migration. This is not the case in laboratory or commercial rearing, where after a few generations, all individuals can be infected.

List of protozoan diseases in humans:

References

Bibliography

; General * Dogiel, V. A., revised by J.I. Poljanskij and E. M. Chejsin. ''General Protozoology'', 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1965. * Hausmann, K., N. Hulsmann. ''Protozoology''. Thieme Verlag; New York, 1996. * Kudo, R.R. '' Protozoology''. Springfield, Illinois: C.C. Thomas, 1954; 4th ed. * Manwell, R.D. ''Introduction to Protozoology'', second revised edition, Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1968. * Roger Anderson, O. ''Comparative protozoology: ecology, physiology, life history''. Berlin tc. Springer-Verlag, 1988. * Sleigh, M. ''The Biology of Protozoa''. E. Arnold: London, 1981. ; Identification * Jahn, T.L.- Bovee, E.C. & Jahn, F.F. ''How to Know the Protozoa''. Wm. C. Brown Publishers, Div. of McGraw Hill, Dubuque, Iowa, 1979; 2nd ed. * Lee, J.J., Leedale, G.F. & Bradbury, P. ''An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa''. Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A: Society of Protozoologists, 2000; 2nd ed. * Patterson, D.J. ''Free-Living Freshwater Protozoa. A Colour Guide''. Manson Publishing; London, 1996. * Patterson, D.J., M.A. Burford. ''A Guide to the Protozoa of Marine Aquaculture Ponds''. CSIRO Publishing, 2001. ; Morphology * Harrison, F.W., Corliss, J.O. (ed.). 1991. ''Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates'', vol. 1, Protozoa. New York: Wiley-Liss, 512 pp. * Pitelka, D. R. 1963''Electron-Microscopic Structure of Protozoa''

Pergamon Press, Oxford. ; Physiology and biochemistry * Nisbet, B. 1984. ''Nutrition and feeding strategies in Protozoa.'' Croom Helm Publ., London, 280 pp. * Coombs, G.H. & North, M. 1991. ''Biochemical protozoology''. Taylor & Francis, London, Washington. * Laybourn-Parry J. 1984. ''A Functional Biology of Free-Living Protozoa''. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. * Levandowski, M., S.H. Hutner (eds). 1979. ''Biochemistry and physiology of protozoa''. Volumes 1, 2, and 3. Academic Press: New York, NY; 2nd ed. * Sukhareva-Buell, N.N. 2003. ''Biologically active substances of protozoa''. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ; Ecology * Capriulo, G.M. (ed.). 1990. ''Ecology of Marine Protozoa.'' Oxford Univ. Press, New York. * Darbyshire, J.F. (ed.). 1994. ''Soil Protozoa.'' CAB International: Wallingford, U.K. 2009 pp. * Laybourn-Parry, J. 1992. ''Protozoan plankton ecology.'' Chapman & Hall, New York. 213 pp. * Fenchel, T. 1987. ''Ecology of protozoan: The biology of free-living phagotrophic protists.'' Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 197 pp. ; Parasitology * Kreier, J.P. (ed.). 1991–1995. ''Parasitic Protozoa'', 2nd ed. 10 vols (1-3 coedited by Baker, J.R.). Academic Press, San Diego, California

; Methods * Lee, J. J., & Soldo, A. T. (1992). ''Protocols in protozoology''. Kansas, USA: Society of Protozoologists, Lawrence

External links

* {{Authority control 1670s in science Obsolete eukaryote taxa Paraphyletic groups