problem of two emperors on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The problem of two emperors or two-emperors problem (deriving from the

The problem of two emperors or two-emperors problem (deriving from the

Following the fall of the

Following the fall of the  In 797 the young emperor

In 797 the young emperor

Most of the great empires in history were in one way or another universal monarchies: they recognized no other state or empire as equal to them and claimed that the entire world (and all the people in it), or even the entire universe, was theirs to rule by right. Since no empire ever ruled the entire known world, unconquered and unincorporated people were usually treated as either unworthy of further attention since they were

Most of the great empires in history were in one way or another universal monarchies: they recognized no other state or empire as equal to them and claimed that the entire world (and all the people in it), or even the entire universe, was theirs to rule by right. Since no empire ever ruled the entire known world, unconquered and unincorporated people were usually treated as either unworthy of further attention since they were

Though the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire itself never stopped referring to themselves as "Romans" ('' Rhomaioi''), sources from Western Europe from the coronation of Charlemagne and onwards denied the Roman legacy of the eastern empire by referring to its inhabitants as "Greeks". The idea behind this renaming was that Charlemagne's coronation did not represent a division (''divisio imperii'') of the Roman Empire into West and East nor a restoration ('' renovatio imperii'') of the old Western Roman Empire. Rather, Charlemagne's coronation was the transfer (''

Though the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire itself never stopped referring to themselves as "Romans" ('' Rhomaioi''), sources from Western Europe from the coronation of Charlemagne and onwards denied the Roman legacy of the eastern empire by referring to its inhabitants as "Greeks". The idea behind this renaming was that Charlemagne's coronation did not represent a division (''divisio imperii'') of the Roman Empire into West and East nor a restoration ('' renovatio imperii'') of the old Western Roman Empire. Rather, Charlemagne's coronation was the transfer ('' In response to the Frankish adoption of the imperial title, the Byzantine emperors (which had previously simply used "emperor" as a title) adopted the full title of "emperor of the Romans" to make their supremacy clear. To the Byzantines, Charlemagne's coronation was a rejection of their perceived order of the world and an act of usurpation. Although Emperor Michael I eventually relented and recognized Charlemagne as an emperor and a "spiritual brother" of the eastern emperor, Charlemagne was not recognized as the ''Roman'' emperor and his ''imperium'' was seen as limited to his actual domains (as such not universal) and not as something that would outlive him (with his successors being referred to as "kings" rather than emperors in Byzantine sources).

Following Charlemagne's coronation, the two empires engaged in diplomacy with each other. The exact terms discussed are unknown and negotiations were slow but it seems that Charlemagne proposed in 802 that he and Irene would marry and unite their empires. As such, the empire could have "reunited" without arguments as to which ruler was the legitimate one. This plan failed however, as the message only arrived in Constantinople after Irene had been deposed and exiled by a new emperor,

In response to the Frankish adoption of the imperial title, the Byzantine emperors (which had previously simply used "emperor" as a title) adopted the full title of "emperor of the Romans" to make their supremacy clear. To the Byzantines, Charlemagne's coronation was a rejection of their perceived order of the world and an act of usurpation. Although Emperor Michael I eventually relented and recognized Charlemagne as an emperor and a "spiritual brother" of the eastern emperor, Charlemagne was not recognized as the ''Roman'' emperor and his ''imperium'' was seen as limited to his actual domains (as such not universal) and not as something that would outlive him (with his successors being referred to as "kings" rather than emperors in Byzantine sources).

Following Charlemagne's coronation, the two empires engaged in diplomacy with each other. The exact terms discussed are unknown and negotiations were slow but it seems that Charlemagne proposed in 802 that he and Irene would marry and unite their empires. As such, the empire could have "reunited" without arguments as to which ruler was the legitimate one. This plan failed however, as the message only arrived in Constantinople after Irene had been deposed and exiled by a new emperor,

One of the primary resources in regards to the problem of two emperors in the Carolingian period is a letter by

One of the primary resources in regards to the problem of two emperors in the Carolingian period is a letter by  Louis also derived legitimacy from religion. He argued that as the Pope of Rome, who actually controlled the city, had rejected the religious leanings of the Byzantines as heretical and instead favored the Franks and because the Pope had also crowned him emperor, Louis was the legitimate Roman emperor. The idea was that it was God himself, acting through his vicar the Pope, who had granted the church, people and city of Rome to him to govern and protect. Louis's letter details that if he was not the emperor of the Romans then he could not be the emperor of the Franks either, as it was the Roman people themselves who had accorded his ancestors with the imperial title. In contrast to the papal affirmation of his imperial lineage, Louis chastized the eastern empire for its emperors mostly only being affirmed by their

Louis also derived legitimacy from religion. He argued that as the Pope of Rome, who actually controlled the city, had rejected the religious leanings of the Byzantines as heretical and instead favored the Franks and because the Pope had also crowned him emperor, Louis was the legitimate Roman emperor. The idea was that it was God himself, acting through his vicar the Pope, who had granted the church, people and city of Rome to him to govern and protect. Louis's letter details that if he was not the emperor of the Romans then he could not be the emperor of the Franks either, as it was the Roman people themselves who had accorded his ancestors with the imperial title. In contrast to the papal affirmation of his imperial lineage, Louis chastized the eastern empire for its emperors mostly only being affirmed by their

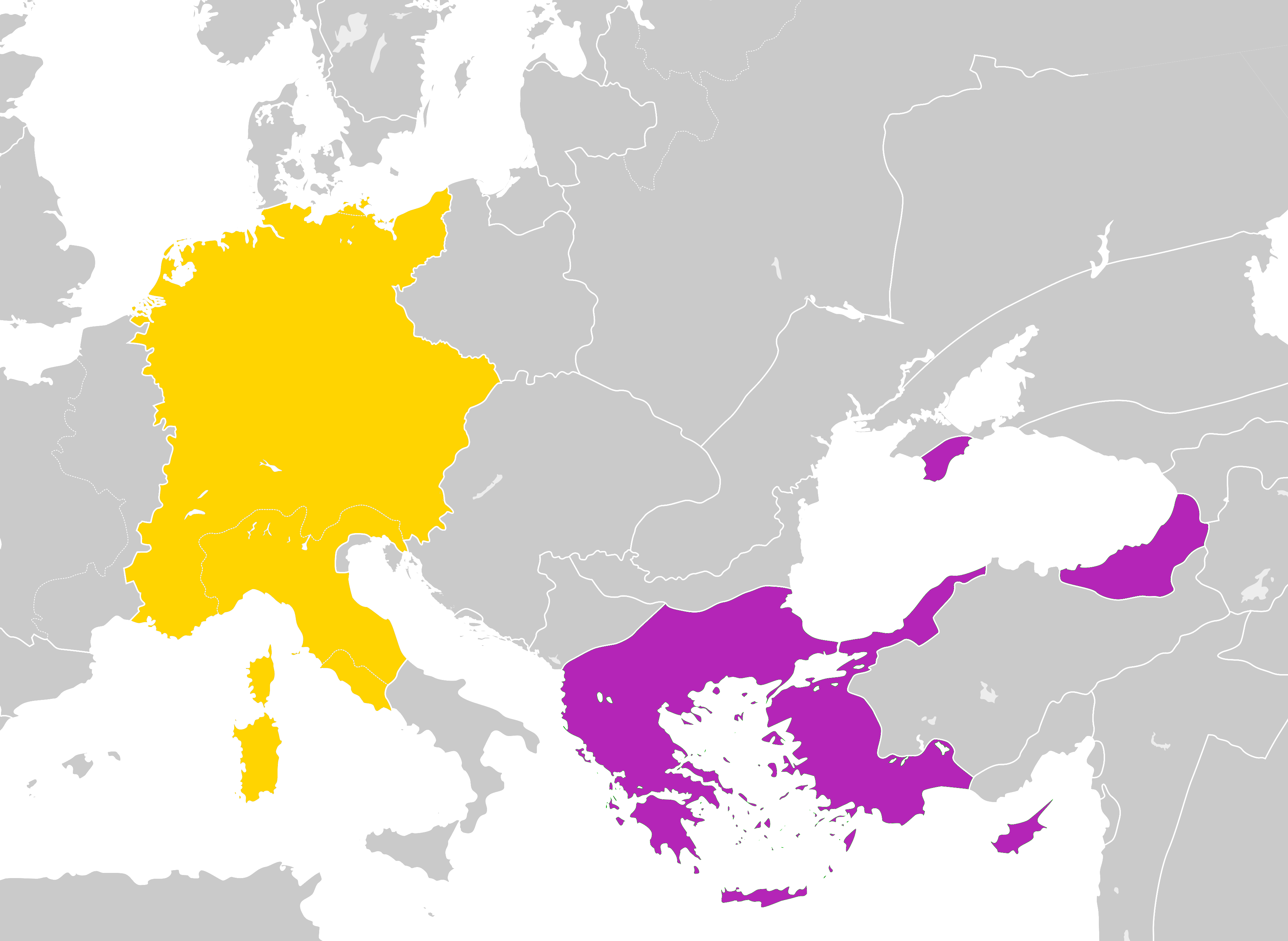

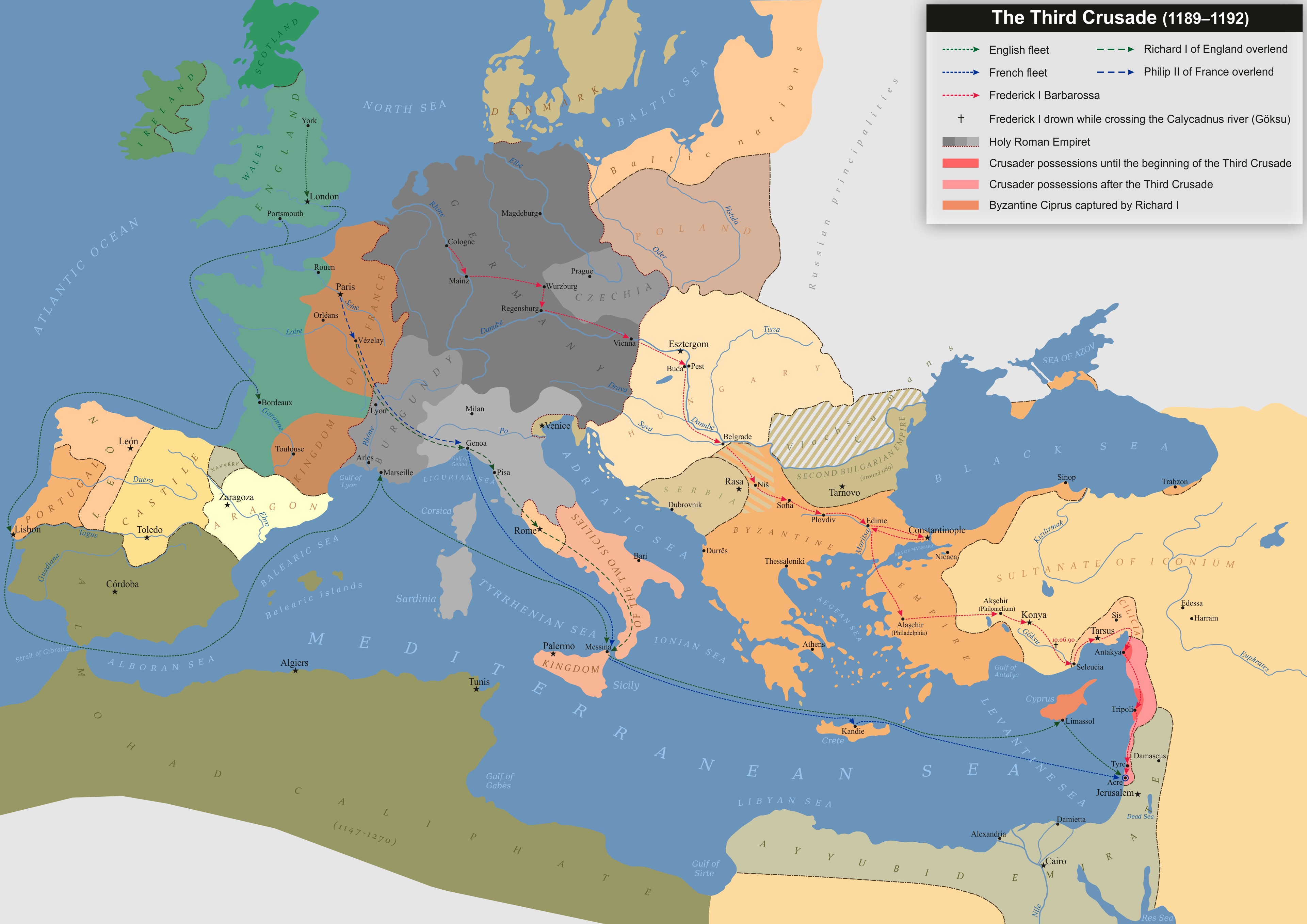

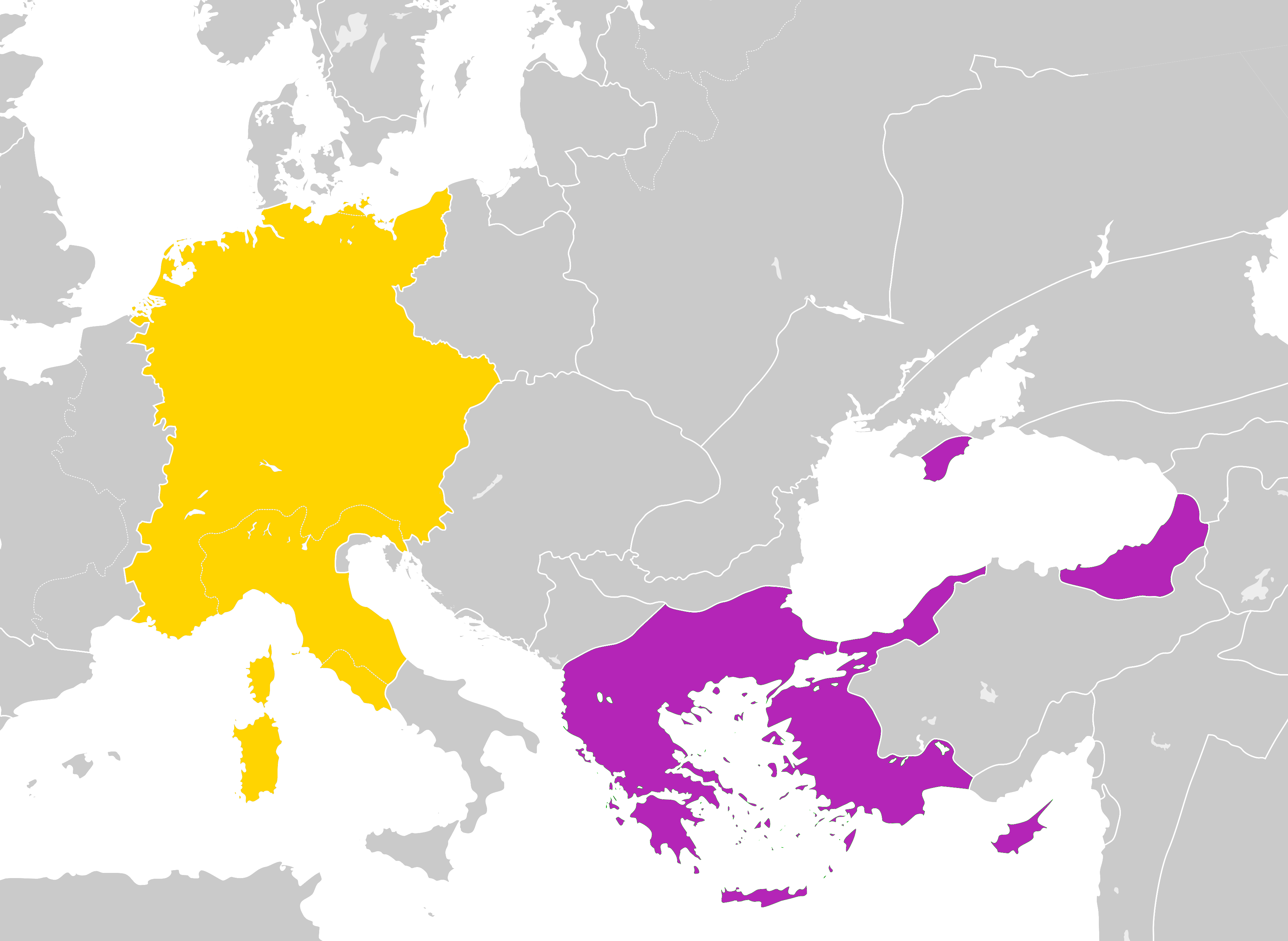

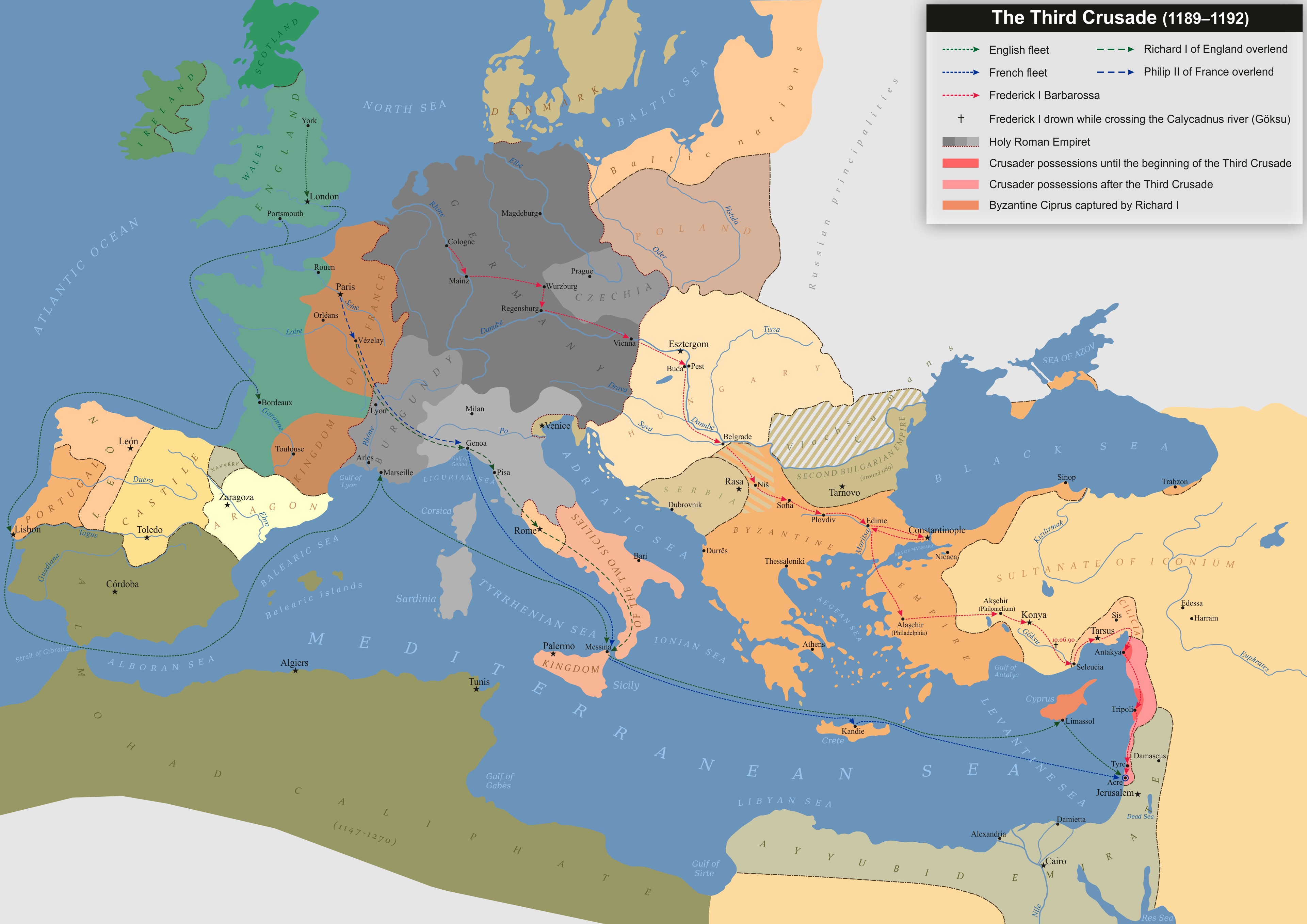

The problem of two emperors returned when

The problem of two emperors returned when

Isaac II panicked and issued contradictory orders to the governor of the city of Philippopolis, one of the strongest fortresses in

Isaac II panicked and issued contradictory orders to the governor of the city of Philippopolis, one of the strongest fortresses in  The Byzantines continued to harass the Germans. The wine left behind in the abandoned city of Philippopolis had been poisoned, and a second embassy sent from the city to Constantinople by Barbarossa was also imprisoned, though shortly thereafter Isaac II relented and released both embassies. When the embassies reunited with Barbarossa at Philippopolis they told the Holy Roman emperor of Isaac II's alliance with Saladin, and claimed that the Byzantine emperor intended to destroy the German army while it was crossing the

The Byzantines continued to harass the Germans. The wine left behind in the abandoned city of Philippopolis had been poisoned, and a second embassy sent from the city to Constantinople by Barbarossa was also imprisoned, though shortly thereafter Isaac II relented and released both embassies. When the embassies reunited with Barbarossa at Philippopolis they told the Holy Roman emperor of Isaac II's alliance with Saladin, and claimed that the Byzantine emperor intended to destroy the German army while it was crossing the

Frederick Barbarossa died before reaching the Holy Land and his son and successor, Henry VI, pursued a foreign policy in which he aimed to force the Byzantine court to accept him as the superior (and sole legitimate) emperor. By 1194, Henry had successfully consolidated Italy under his own rule after being crowned as King of Sicily, in addition to already being the Holy Roman emperor and the King of Italy, and he turned his gaze east. The Muslim world had fractured after Saladin's death and Barbarossa's crusade had revealed the Byzantine Empire to be weak and also given a useful ''casus belli'' for attack. Furthermore, Leo II, the ruler of

Frederick Barbarossa died before reaching the Holy Land and his son and successor, Henry VI, pursued a foreign policy in which he aimed to force the Byzantine court to accept him as the superior (and sole legitimate) emperor. By 1194, Henry had successfully consolidated Italy under his own rule after being crowned as King of Sicily, in addition to already being the Holy Roman emperor and the King of Italy, and he turned his gaze east. The Muslim world had fractured after Saladin's death and Barbarossa's crusade had revealed the Byzantine Empire to be weak and also given a useful ''casus belli'' for attack. Furthermore, Leo II, the ruler of

A series of events and the intervention of

A series of events and the intervention of  The Latin Emperors saw the term ''Romanorum'' or ''Romani'' in a new light, not seeing it as referring to the Western idea of "geographic Romans" (inhabitants of the city of Rome) but not adopting the Byzantine idea of the "ethnic Romans" (Greek-speaking citizens of the Byzantine Empire) either. Instead, they saw the term as a political identity encapsulating all subjects of the Roman emperor, i.e. all the subjects of their multi-national empire (whose ethnicities encompassed Latins, "Greeks", Armenians and Bulgarians).

The embracing of the Roman nature of the emperorship in Constantinople would have brought the Latin emperors into conflict with the idea of ''translatio imperii''. Furthermore, the Latin emperors claimed the dignity of ''Deo coronatus'' (as the Byzantine emperors had claimed before them), a dignity the Holy Roman emperors could not claim, being dependent on the Pope for their coronation. Despite the fact that the Latin emperors would have recognized the Holy Roman Empire as ''the'' Roman Empire, they nonetheless claimed a position that was at least equal to that of the Holy Roman emperors. In 1207–1208, Latin emperor Henry proposed to marry the daughter of the elected ''rex Romanorum'' in the Holy Roman Empire, Henry VI's brother Philip of Swabia, yet to be crowned emperor due to an ongoing struggle with the rival claimant Otto of Brunswick. Philip's envoys responded that Henry was an ''advena'' (stranger; outsider) and ''solo nomine imperator'' (emperor in name only) and that the marriage proposal would only be accepted if Henry recognized Philip as the ''imperator Romanorum'' and ''suus dominus'' (his master). As no marriage occurred, it is clear that submission to the Holy Roman emperor was not considered an option.

The emergence of the Latin Empire and the submission of Constantinople to the Catholic Church as facilitated by its emperors altered the idea of ''translatio imperii'' into what was called ''divisio imperii'' (division of empire). The idea, which became accepted by

The Latin Emperors saw the term ''Romanorum'' or ''Romani'' in a new light, not seeing it as referring to the Western idea of "geographic Romans" (inhabitants of the city of Rome) but not adopting the Byzantine idea of the "ethnic Romans" (Greek-speaking citizens of the Byzantine Empire) either. Instead, they saw the term as a political identity encapsulating all subjects of the Roman emperor, i.e. all the subjects of their multi-national empire (whose ethnicities encompassed Latins, "Greeks", Armenians and Bulgarians).

The embracing of the Roman nature of the emperorship in Constantinople would have brought the Latin emperors into conflict with the idea of ''translatio imperii''. Furthermore, the Latin emperors claimed the dignity of ''Deo coronatus'' (as the Byzantine emperors had claimed before them), a dignity the Holy Roman emperors could not claim, being dependent on the Pope for their coronation. Despite the fact that the Latin emperors would have recognized the Holy Roman Empire as ''the'' Roman Empire, they nonetheless claimed a position that was at least equal to that of the Holy Roman emperors. In 1207–1208, Latin emperor Henry proposed to marry the daughter of the elected ''rex Romanorum'' in the Holy Roman Empire, Henry VI's brother Philip of Swabia, yet to be crowned emperor due to an ongoing struggle with the rival claimant Otto of Brunswick. Philip's envoys responded that Henry was an ''advena'' (stranger; outsider) and ''solo nomine imperator'' (emperor in name only) and that the marriage proposal would only be accepted if Henry recognized Philip as the ''imperator Romanorum'' and ''suus dominus'' (his master). As no marriage occurred, it is clear that submission to the Holy Roman emperor was not considered an option.

The emergence of the Latin Empire and the submission of Constantinople to the Catholic Church as facilitated by its emperors altered the idea of ''translatio imperii'' into what was called ''divisio imperii'' (division of empire). The idea, which became accepted by

With the Byzantine reconquest of Constantinople in 1261 under Emperor

With the Byzantine reconquest of Constantinople in 1261 under Emperor

The dispute between the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire was mostly confined to the realm of diplomacy, never fully exploding into open war. This was probably mainly due to the great geographical distance separating the two empires; a large-scale campaign would have been infeasible to undertake for either emperor. Events in Germany, France and the west in general was of little compelling interest to the Byzantines as they firmly believed that the western provinces would eventually be reconquered. Of more compelling interest were political developments in their near vicinity and in 913, the ''Knyaz'' (prince or king) of

The dispute between the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire was mostly confined to the realm of diplomacy, never fully exploding into open war. This was probably mainly due to the great geographical distance separating the two empires; a large-scale campaign would have been infeasible to undertake for either emperor. Events in Germany, France and the west in general was of little compelling interest to the Byzantines as they firmly believed that the western provinces would eventually be reconquered. Of more compelling interest were political developments in their near vicinity and in 913, the ''Knyaz'' (prince or king) of

With the

With the  The problem of two emperors and the dispute between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire would be finally resolved after the two empires signed a peace treaty following a string of Ottoman defeats. In the 1606

The problem of two emperors and the dispute between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire would be finally resolved after the two empires signed a peace treaty following a string of Ottoman defeats. In the 1606

By the time of the first embassy from the Holy Roman Empire to

By the time of the first embassy from the Holy Roman Empire to

Translation of Carolingian Emperor Louis II's 871 letter to Byzantine Emperor Basil I

Translation of Liutprand of Cremona's report on his 967/968 mission to Constantinople

History of the Byzantine Empire History of the Ottoman Empire International disputes Medieval politics Naming controversies Politics of the Holy Roman Empire Former monarchies of Europe Rival successions Byzantine Empire–Carolingian Empire relations Byzantine Empire–Holy Roman Empire relations

The problem of two emperors or two-emperors problem (deriving from the

The problem of two emperors or two-emperors problem (deriving from the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

term ''Zweikaiserproblem'')The term was introduced in the first major treatise on the issue, by W. Ohnsorge, cf. . is the historiographical

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

term for the historical contradiction between the idea of the universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of NBCUniversal

** Universal TV, a t ...

empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

, that there was only ever one true emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

at any one given time, and the truth that there were often multiple individuals who claimed the position simultaneously. The term is primarily used in regards to medieval European history and often refers to in particular the long-lasting dispute between the Byzantine emperors

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as ...

in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and the Holy Roman emperors

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

in modern-day Germany and Austria as to which monarch represented the legitimate Roman emperor.

In the view of medieval Christians, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

was indivisible and its emperor held a somewhat hegemonic position even over Christians who did not live within the formal borders of the empire. Since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

during Late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English h ...

, the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

(which represented its surviving provinces in the East) had been recognized by itself, the pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and the various new Christian kingdoms throughout Europe as the legitimate Roman Empire. This changed in 797 when Emperor Constantine VI

Constantine VI ( gr, Κωνσταντῖνος, ''Kōnstantinos''; 14 January 771 – before 805Cutler & Hollingsworth (1991), pp. 501–502) was Byzantine emperor from 780 to 797. The only child of Emperor Leo IV, Constantine was named co-emp ...

was deposed, blinded, and replaced as ruler by his mother, Empress Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United State ...

, whose rule was ultimately not accepted in Western Europe, the most frequently cited reason being that she was a woman. Rather than recognizing Irene, Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position ...

proclaimed the king of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who c ...

, Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

, as the emperor of the Romans in 800 under the concept of ''translatio imperii

''Translatio imperii'' (Latin for "transfer of rule") is a historiographical concept that originated from the Middle Ages, in which history is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an ''imperium'' that invests supreme power in a singular r ...

'' (transfer of imperial power).

Although the two empires eventually relented and recognized each other's rulers as emperors, they never explicitly recognized the other as "Roman", with the Byzantines referring to the Holy Roman emperor as the 'emperor (or king) of the Franks' and later as the 'king of Germany' and the western sources often describing the Byzantine emperor as the 'emperor of the Greeks' or the 'emperor of Constantinople'. Over the course of the centuries after Charlemagne's coronation, the dispute in regards to the imperial title was one of the most contested issues in Holy Roman–Byzantine politics and though military action rarely resulted because of it, the dispute significantly soured diplomacy between the two empires. This lack of war was probably mostly on account of the geographical distance between the two empires. On occasion, the imperial title was claimed by neighbors of the Byzantine Empire, such as Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

, which often led to military confrontations.

After the Byzantine Empire was momentarily overthrown by the Catholic crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

of the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

in 1204 and supplanted by the Latin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byza ...

, the dispute continued even though both emperors now followed the same religious head for the first time since the dispute began. Though the Latin emperors recognized the Holy Roman emperors as the legitimate Roman emperors, they also claimed the title for themselves, which was not recognized by the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

in return. Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

eventually accepted the idea of ''divisio imperii'' (division of empire), in which imperial hegemony would be divided into West (the Holy Roman Empire) and East (the Latin Empire). Although the Latin Empire was destroyed by the resurgent Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty

The House of Palaiologos ( Palaiologoi; grc-gre, Παλαιολόγος, pl. , female version Palaiologina; grc-gre, Παλαιολογίνα), also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greek f ...

in 1261, the Palaiologoi never reached the power of the pre-1204 Byzantine Empire and its emperors ignored the problem of two emperors in favor of closer diplomatic ties with the west due to a need for aid against the many enemies of their empire.

The problem of two emperors only fully resurfaced after the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

in 1453, after which the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

claimed the imperial dignity as ''Kayser-i Rûm'' (Caesar of the Roman Empire) and aspired to claim universal hegemony. The Ottoman sultans were recognized as emperors by the Holy Roman Empire in the 1533 Treaty of Constantinople, but the Holy Roman emperors were not recognized as emperors in turn. The Ottomans called the Holy Roman emperors by the title ''kıral'' (king) for one and a half centuries, until the Sultan Ahmed I

Ahmed I ( ota, احمد اول '; tr, I. Ahmed; 18 April 1590 – 22 November 1617) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1603 until his death in 1617. Ahmed's reign is noteworthy for marking the first breach in the Ottoman tradition of royal f ...

formally recognized Emperor Rudolf II as an emperor in the Peace of Zsitvatorok

The Peace of Zsitvatorok (or Treaty of Sitvatorok) was a peace treaty which ended the 15-year Long Turkish War between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy on 11 November 1606. The treaty was part of a system of peace treaties which put ...

in 1606, an acceptance of ''divisio imperii'', bringing an end to the dispute between Constantinople and Western Europe. In addition to the Ottomans, the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I ...

and the later Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

also claimed the Roman legacy of the Byzantine Empire, with its rulers titling themselves as ''tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

'' (deriving from "caesar") and later ''imperator''. Their claim to the imperial title was rejected by the Holy Roman emperors until 1726, when Charles VI recognized it as part of brokering an alliance, though he refused to admit that the two monarchs held equal status.

Background

Political background

Following the fall of the

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in the 5th century, Roman civilization endured in the remaining eastern half of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, often termed by historians as the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

(though it self-identified simply as the "Roman Empire"). As the Roman emperors had done in antiquity, the Byzantine emperors

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as ...

saw themselves as universal rulers. The idea was that the world contained one empire (the Roman Empire) and one church and this idea survived despite the collapse of the empire's western provinces. Although the last extensive attempt at putting the theory back into practice had been Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

's wars of reconquest in the 6th century, which saw the return of Italy and Africa into imperial control, the idea of a great western reconquest remained a dream for Byzantine emperors for centuries.

Because the empire was constantly threatened at critical frontiers to its north and east, the Byzantines were unable to focus much attention to the west and Roman control would slowly disappear in the west once more. Nevertheless, their claim to the universal empire was acknowledged by temporal and religious authorities in the west, even if this empire couldn't be physically restored. Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

and Frankish kings in the fifth and sixth centuries acknowledged the emperor's suzerainty, as a symbolic acknowledgement of membership in the Roman Empire also enhanced their own status and granted them a position in the perceived world order of the time. As such, Byzantine emperors could still perceive the west as the western part of ''their'' empire, momentarily in barbarian hands, but still formally under their control through a system of recognition and honors bestowed on the western kings by the emperor.

A decisive geopolitical turning point in the relations between East and West was during the long reign of emperor Constantine V

Constantine V ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantīnos; la, Constantinus; July 718 – 14 September 775), was Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able ...

(741–775). Though Constantine V conducted several successful military campaigns against the enemies of his empire, his efforts were centered on the Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as noma ...

, who represented immediate threats. Because of this, the defense of Italy was neglected. The main Byzantine administrative unit in Italy, the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

, fell to the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

in 751, ending the Byzantine presence in northern Italy. The collapse of the Exarchate had long-standing consequences. The popes

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, ostensibly Byzantine vassals, realized that Byzantine support was no longer a guarantee and increasingly began relying on the major kingdom in the West, the Frankish Kingdom, for support against the Lombards. Byzantine possessions throughout Italy, such as Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, began to raise their own militias and effectively became independent. Imperial authority ceased to be exercised in Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

and religious authority in southern Italy was formally transferred by the emperors from the popes to the patriarchs of Constantinople. The Mediterranean world, interconnected since the days of Roman Empire of old, had been definitely divided into East and West.

In 797 the young emperor

In 797 the young emperor Constantine VI

Constantine VI ( gr, Κωνσταντῖνος, ''Kōnstantinos''; 14 January 771 – before 805Cutler & Hollingsworth (1991), pp. 501–502) was Byzantine emperor from 780 to 797. The only child of Emperor Leo IV, Constantine was named co-emp ...

was arrested, deposed and blinded by his mother and former regent, Irene of Athens

Irene of Athens ( el, Εἰρήνη, ; 750/756 – 9 August 803), surname Sarantapechaina (), was Byzantine empress consort to Emperor Leo IV from 775 to 780, regent during the childhood of their son Constantine VI from 780 until 790, co-ruler ...

. She then governed the empire as its sole ruler, taking the title ''Basileus

''Basileus'' ( el, ) is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs in history. In the English-speaking world it is perhaps most widely understood to mean " monarch", referring to either a " king" or an "emperor" and ...

'' rather than the feminine form ''Basilissa'' (used for the empresses who were wives of reigning emperors). At the same time, the political situation in the West was rapidly changing. The Frankish Kingdom had been reorganized and revitalized under king Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

. Though Irene had been on good terms with the papacy prior to her usurpation of the Byzantine throne, the act soured her relations with Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position ...

. At the same time, Charlemagne's courtier Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

had suggested that the imperial throne was now vacant since a woman claimed to be emperor, perceived as a symptom of the decadence of the empire in the east. Possibly inspired by these ideas and possibly viewing the idea of a woman emperor as an abomination, Pope Leo III also began to see the imperial throne as vacant. When Charlemagne visited Rome for Christmas in 800 he was treated not as one territorial ruler among others, but as the sole legitimate monarch in Europe and on Christmas Day he was proclaimed and crowned by Pope Leo III as the Emperor of the Romans.

Rome and the idea of the Universal Empire

Most of the great empires in history were in one way or another universal monarchies: they recognized no other state or empire as equal to them and claimed that the entire world (and all the people in it), or even the entire universe, was theirs to rule by right. Since no empire ever ruled the entire known world, unconquered and unincorporated people were usually treated as either unworthy of further attention since they were

Most of the great empires in history were in one way or another universal monarchies: they recognized no other state or empire as equal to them and claimed that the entire world (and all the people in it), or even the entire universe, was theirs to rule by right. Since no empire ever ruled the entire known world, unconquered and unincorporated people were usually treated as either unworthy of further attention since they were barbarians

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be les ...

, or they were looked over entirely through imperial ceremonies and ideology disguising reality. The allure of universal empires is the idea of universal peace; if all of humanity is united under one empire, war is theoretically impossible. Though the Roman Empire is an example of a "universal empire" in this sense, the idea is not exclusive to the Romans, having been expressed in unrelated entities such as the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance ( nci, Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ was an alliance of three Nahua city-states: , , and . These three city-states ruled that area in and around the Valley of Mexi ...

and in earlier realms such as the Persian and Assyrian Empires.

Most "universal emperors" justified their ideology and actions through the divine; proclaiming themselves (or being proclaimed by others) as either divine themselves or as appointed on the behalf of the divine, meaning that their rule was theoretically sanctioned by heaven. By tying together religion with the empire and its ruler, obedience to the empire became the same thing as obedience to the divine. Like its predecessors, the Ancient Roman religion

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

functioned in much the same way, conquered peoples were expected to participate in the imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may ...

regardless of their faith before Roman conquest. This imperial cult was threatened by religions such as Christianity (where Jesus Christ is explicitly proclaimed as the "Lord"), which is one of the primary reasons for the harsh persecutions of Christians during the early centuries of the Roman Empire; the religion was a direct threat to the ideology of the regime. Although Christianity eventually became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, the imperial ideology was far from unrecognizable after its adoption. Like the previous imperial cult, Christianity now held the empire together and though the emperors were no longer recognized as gods, the emperors had successfully established themselves as the rulers of the Christian church in the place of Christ, still uniting temporal and spiritual authority.

In the Byzantine Empire, the authority of the emperor as both the rightful temporal ruler of the Roman Empire and the head of Christianity remained unquestioned until the fall of the empire in the 15th century. The Byzantines firmly believed that their emperor was God's appointed ruler and his viceroy on Earth (illustrated in their title as ''Deo coronatus'', "crowned by God"), that he was the Roman emperor (''basileus ton Rhomaion''), and as such the highest authority in the world due to his universal and exclusive emperorship. The emperor was an absolute ruler dependent on no one when exercising his power (illustrated in their title as ''autokrator

''Autokrator'' or ''Autocrator'' ( grc-gre, αὐτοκράτωρ, autokrátōr, , self-ruler," "one who rules by himself," whence English "autocrat, from grc, αὐτός, autós, self, label=none + grc, κράτος, krátos, dominion, power ...

'', or the Latin ''moderator''). The Emperor was adorned with an aura of holiness and was theoretically not accountable to anyone but God himself. The Emperor's power, as God's viceroy on Earth, was also theoretically unlimited. In essence, Byzantine imperial ideology was simply a christianization of the old Roman imperial ideology, which had also been universal and absolutist.

As the Western Roman Empire collapsed and subsequent Byzantine attempts to retain the west crumbled, the church took the place of the empire in the west and by the time Western Europe emerged from the chaos endured during the 5th to 7th centuries, the pope was the chief religious authority and the Franks were the chief temporal authority. Charlemagne's coronation as Roman emperor expressed an idea different from the absolutist ideas of the emperors in the Byzantine Empire. Though the eastern emperor retained control of both the temporal empire and the spiritual church, the rise of a new empire in the west was a collaborative effort, Charlemagne's temporal power had been won through his wars, but he had received the imperial crown from the pope. Both the emperor and the pope had claims to ultimate authority in Western Europe (the popes as the successors of Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

and the emperors as divinely appointed protectors of the church) and though they recognized the authority of each other, their "dual rule" would give rise to many controversies (such as the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest (German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

and the rise and fall of several antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mi ...

s).

Holy Roman–Byzantine dispute

Carolingian period

Imperial ideology

Though the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire itself never stopped referring to themselves as "Romans" ('' Rhomaioi''), sources from Western Europe from the coronation of Charlemagne and onwards denied the Roman legacy of the eastern empire by referring to its inhabitants as "Greeks". The idea behind this renaming was that Charlemagne's coronation did not represent a division (''divisio imperii'') of the Roman Empire into West and East nor a restoration ('' renovatio imperii'') of the old Western Roman Empire. Rather, Charlemagne's coronation was the transfer (''

Though the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire itself never stopped referring to themselves as "Romans" ('' Rhomaioi''), sources from Western Europe from the coronation of Charlemagne and onwards denied the Roman legacy of the eastern empire by referring to its inhabitants as "Greeks". The idea behind this renaming was that Charlemagne's coronation did not represent a division (''divisio imperii'') of the Roman Empire into West and East nor a restoration ('' renovatio imperii'') of the old Western Roman Empire. Rather, Charlemagne's coronation was the transfer (''translatio imperii

''Translatio imperii'' (Latin for "transfer of rule") is a historiographical concept that originated from the Middle Ages, in which history is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an ''imperium'' that invests supreme power in a singular r ...

'') of the ''imperium Romanum'' from the Greeks in the east to the Franks in the west. To contemporaries in Western Europe, Charlemagne's key legitimizing factor as emperor (other than papal approval) was the territories which he controlled. As he controlled formerly Roman lands in Gaul, Germany and Italy (including Rome itself), and acted as a true emperor in these lands, which the eastern emperor was seen as having had abandoned, he thus deserved to be called an emperor.

Although crowned as an explicit refusal of the eastern emperor's claim to universal rule, Charlemagne himself does not appear to have been interested in confrontation with the Byzantine Empire or its rulers. When Charlemagne was crowned by Pope Leo III, the title he was bestowed with was simply ''Imperator''. When he wrote to Constantinople in 813, Charlemagne titled himself as the "emperor and augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

and also king of the Franks and of the Lombards", identifying the imperial title with his previous royal titles in regards to the Franks and Lombards, rather than to the Romans. As such, his imperial title could be seen as stemming from the fact that he was the king of more than one kingdom (equating the title of emperor with that of king of kings

King of Kings; grc-gre, Βασιλεὺς Βασιλέων, Basileùs Basiléōn; hy, արքայից արքա, ark'ayits ark'a; sa, महाराजाधिराज, Mahārājadhirāja; ka, მეფეთ მეფე, ''Mepet mepe'' ...

), rather than as an usurpation of Byzantine power.

On his coins, the name and title used by Charlemagne is ''Karolus Imperator Augustus'' and in his own documents he used ''Imperator Augustus Romanum gubernans Imperium'' ("august emperor, governing the Roman Empire") and ''serenissimus Augustus a Deo coronatus, magnus pacificus Imperator Romanorum gubernans Imperium'' ("most serene Augustus crowned by God, great peaceful emperor governing the empire of the Romans"). The identification as an "emperor governing the Roman Empire" rather than a "Roman emperor" could be seen as an attempt at avoiding the dispute and issue over who was the true emperor and attempting to keep the perceived unity of the empire intact.

In response to the Frankish adoption of the imperial title, the Byzantine emperors (which had previously simply used "emperor" as a title) adopted the full title of "emperor of the Romans" to make their supremacy clear. To the Byzantines, Charlemagne's coronation was a rejection of their perceived order of the world and an act of usurpation. Although Emperor Michael I eventually relented and recognized Charlemagne as an emperor and a "spiritual brother" of the eastern emperor, Charlemagne was not recognized as the ''Roman'' emperor and his ''imperium'' was seen as limited to his actual domains (as such not universal) and not as something that would outlive him (with his successors being referred to as "kings" rather than emperors in Byzantine sources).

Following Charlemagne's coronation, the two empires engaged in diplomacy with each other. The exact terms discussed are unknown and negotiations were slow but it seems that Charlemagne proposed in 802 that he and Irene would marry and unite their empires. As such, the empire could have "reunited" without arguments as to which ruler was the legitimate one. This plan failed however, as the message only arrived in Constantinople after Irene had been deposed and exiled by a new emperor,

In response to the Frankish adoption of the imperial title, the Byzantine emperors (which had previously simply used "emperor" as a title) adopted the full title of "emperor of the Romans" to make their supremacy clear. To the Byzantines, Charlemagne's coronation was a rejection of their perceived order of the world and an act of usurpation. Although Emperor Michael I eventually relented and recognized Charlemagne as an emperor and a "spiritual brother" of the eastern emperor, Charlemagne was not recognized as the ''Roman'' emperor and his ''imperium'' was seen as limited to his actual domains (as such not universal) and not as something that would outlive him (with his successors being referred to as "kings" rather than emperors in Byzantine sources).

Following Charlemagne's coronation, the two empires engaged in diplomacy with each other. The exact terms discussed are unknown and negotiations were slow but it seems that Charlemagne proposed in 802 that he and Irene would marry and unite their empires. As such, the empire could have "reunited" without arguments as to which ruler was the legitimate one. This plan failed however, as the message only arrived in Constantinople after Irene had been deposed and exiled by a new emperor, Nikephoros I

Nikephoros I or Nicephorus I ( gr, Νικηφόρος; 750 – 26 July 811) was Byzantine emperor from 802 to 811. Having served Empress Irene as '' genikos logothetēs'', he subsequently ousted her from power and took the throne himself. In r ...

.

Louis II and Basil I

One of the primary resources in regards to the problem of two emperors in the Carolingian period is a letter by

One of the primary resources in regards to the problem of two emperors in the Carolingian period is a letter by Emperor Louis II

Louis II (825 – 12 August 875), sometimes called the Younger, was the king of Italy and emperor of the Carolingian Empire from 844, co-ruling with his father Lothair I until 855, after which he ruled alone.

Louis's usual title was ''imper ...

. Louis II was the fourth emperor of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the L ...

, though his domain was confined to northern Italy as the rest of the empire had fractured into several different kingdoms, though these still acknowledged Louis as the emperor. His letter was a reply to a provocative letter by Byzantine emperor Basil I the Macedonian

Basil I, called the Macedonian ( el, Βασίλειος ὁ Μακεδών, ''Basíleios ō Makedṓn'', 811 – 29 August 886), was a Byzantine Emperor who reigned from 867 to 886. Born a lowly peasant in the theme of Macedonia, he rose in the ...

. Though Basil's letter is lost, its contents can be ascertained from the known geopolitical situation at the time and Louis's reply and probably related to the ongoing co-operation between the two empires against the Muslims. The focal point of Basil's letter was his refusal to recognize Louis II as a Roman emperor.

Basil appears to have based his refusal on two main points. First of all, the title of Roman emperor was not hereditary (the Byzantines still considered it to formally be a republican office, although also tied intimately with religion) and second of all, it was not considered appropriate for someone of a ''gens'' (e.g. an ethnicity) to hold the title. The Franks, and other groups throughout Europe, were seen as different ''gentes'' but to Basil and the rest of the Byzantines, "Roman" was not a ''gens''. Romans were defined chiefly by their lack of a ''gens'' and as such, Louis was not Roman and thus not a Roman emperor. There was only one Roman emperor, Basil himself, and though Basil considered that Louis could be an emperor of the Franks, he appears to have questioned this as well seeing as only the ruler of the Romans was to be titled ''basileus'' (emperor).

As illustrated by Louis's letter, the western idea of ethnicity was different from the Byzantine idea; everyone belonged to some form of ethnicity. Louis considered the ''gens romana'' (Roman people) to be the people who lived in the city of Rome, which he saw as having been deserted by the Byzantine Empire. All ''gentes'' could be ruled by a ''basileus'' in Louis's mind and as he pointed out, the title (which had originally simply meant "king") had been applied to other rulers in the past (notably Persian rulers). Furthermore, Louis disagreed with the notion that someone of a ''gens'' could not become the Roman emperor. He considered the ''gentes'' of Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

(the Theodosian dynasty

The Theodosian dynasty was a Roman imperial family that produced five Roman emperors during Late Antiquity, reigning over the Roman Empire from 379 to 457. The dynasty's patriarch was Theodosius the Elder, whose son Theodosius the Great was made ...

), Isauria

Isauria ( or ; grc, Ἰσαυρία), in ancient geography, is a rugged, isolated, district in the interior of Asia Minor, of very different extent at different periods, but generally covering what is now the district of Bozkır and its surro ...

(the Isaurian dynasty) and Khazaria

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

( Leo IV) as all having provided emperors, though the Byzantines themselves would have seen all of these as Romans and not as peoples of ''gentes''. The views expressed by the two emperors in regards to ethnicity are somewhat paradoxical; Basil defined the Roman Empire in ethnic terms (defining it as explicitly against ethnicity) despite not considering the Romans as an ethnicity and Louis did not define the Roman Empire in ethnic terms (defining it as an empire of God, the creator of all ethnicities) despite considering the Romans as an ethnic people.

Louis also derived legitimacy from religion. He argued that as the Pope of Rome, who actually controlled the city, had rejected the religious leanings of the Byzantines as heretical and instead favored the Franks and because the Pope had also crowned him emperor, Louis was the legitimate Roman emperor. The idea was that it was God himself, acting through his vicar the Pope, who had granted the church, people and city of Rome to him to govern and protect. Louis's letter details that if he was not the emperor of the Romans then he could not be the emperor of the Franks either, as it was the Roman people themselves who had accorded his ancestors with the imperial title. In contrast to the papal affirmation of his imperial lineage, Louis chastized the eastern empire for its emperors mostly only being affirmed by their

Louis also derived legitimacy from religion. He argued that as the Pope of Rome, who actually controlled the city, had rejected the religious leanings of the Byzantines as heretical and instead favored the Franks and because the Pope had also crowned him emperor, Louis was the legitimate Roman emperor. The idea was that it was God himself, acting through his vicar the Pope, who had granted the church, people and city of Rome to him to govern and protect. Louis's letter details that if he was not the emperor of the Romans then he could not be the emperor of the Franks either, as it was the Roman people themselves who had accorded his ancestors with the imperial title. In contrast to the papal affirmation of his imperial lineage, Louis chastized the eastern empire for its emperors mostly only being affirmed by their senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and sometimes lacking even that, with some emperors having been proclaimed by the army, or worse, women (probably a reference to Irene). Louis probably overlooked that affirmation by the army was the original ancient source for the title of ''imperator

The Latin word ''imperator'' derives from the stem of the verb la, imperare, label=none, meaning 'to order, to command'. It was originally employed as a title roughly equivalent to ''commander'' under the Roman Republic. Later it became a part o ...

'', before it came to mean the ruler of the Roman Empire.

Though it would have been possible for either side of the dispute to concede to the obvious truth, that there were now two empires and two emperors, this would have denied the understood nature of what the empire was and meant (its unity). Louis's letter does offer some evidence that he might have recognized the political situation as such; Louis is referred to as the "august emperor of the Romans" and Basil is referred to as the "very glorious and pious emperor of New Rome", and he suggests that the "indivisible empire" is the empire of God and that "God has not granted this church to be steered either by me or you alone, but so that we should be bound to each other with such love that we cannot be divided, but should seem to exist as one". These references are more likely to mean that Louis still considered there to be a single empire, but with two imperial claimants (in effect an emperor and an anti-emperor). Neither side in the dispute would have been willing to reject the idea of the single empire. Louis referring to the Byzantine emperor as an emperor in the letter may simply be a courtesy, rather than an implication that he truly accepted his imperial rule.

Louis's letter mentions that the Byzantines abandoned Rome, the seat of empire, and lost the Roman way of life and the Latin language. In his view, that the empire was ruled from Constantinople did not represent it surviving, but rather that it had fled from its responsibilities. Although he would have had to approve its contents, Louis probably did not write his letter himself and it was probably instead written by the prominent cleric Anastasius the Librarian. Anastasius was not a Frank but a citizen of the city of Rome (in Louis's view an "ethnic Roman"). As such, prominent figures in Rome itself would have shared Louis's views, illustrating that by his time, the Byzantine Empire and the city of Rome had drifted very far apart.

Following the death of Louis in 875, emperors continued to be crowned in the West for a few decades, but their reigns were often brief and problematic and they only held limited power and as such the problem of two emperors ceased being a major issue to the Byzantines, for a time.

Ottonian period

The problem of two emperors returned when

The problem of two emperors returned when Pope John XII

Pope John XII ( la, Ioannes XII; c. 930/93714 May 964), born Octavian, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 16 December 955 to his death in 964. He was related to the counts of Tusculum, a powerful Roman family which had do ...

crowned the king of Germany, Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

, as emperor of the Romans in 962, almost 40 years after the death of the previous papally crowned emperor, Berengar. Otto's repeated territorial claims to all of Italy and Sicily (as he had also been proclaimed as the king of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader ...

) brought him into conflict with the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine emperor at the time, Romanos II

Romanos II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Ρωμανός, 938 – 15 March 963) was Byzantine Emperor from 959 to 963. He succeeded his father Constantine VII at the age of twenty-one and died suddenly and mysteriously four years later. His son Bas ...

, appears to have more or less ignored Otto's imperial aspirations, but the succeeding Byzantine emperor, Nikephoros II, was strongly opposed to them. Otto, who hoped to secure imperial recognition and the provinces in southern Italy diplomatically through a marriage alliance, dispatched diplomatic envoys to Nikephoros in 967. To the Byzantines, Otto's coronation was a blow as, or even more, serious than Charlemagne's as Otto and his successors insisted on the Roman aspect of their ''imperium'' more strongly than their Carolingian predecessors.

Leading Otto's diplomatic mission was Liutprand of Cremona

Liutprand, also Liudprand, Liuprand, Lioutio, Liucius, Liuzo, and Lioutsios (c. 920 – 972),"LIUTPRAND OF CREMONA" in '' The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'', Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 1241. was a historian, diplomat, ...

, who chastized the Byzantines for their perceived weakness; losing control of the West and thus also causing the pope to lose control of the lands which belonged to him. To Liutprand, the fact that Otto I had acted as a restorer and protector of the church by restoring the lands of the Papacy (which Liutprand believed had been granted to the pope by Emperor Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

), made him the true emperor while the loss of these lands under preceding Byzantine rule illustrated that the Byzantines were weak and unfit to be emperors. Liutprand expresses his ideas with the following words in his report on the mission, in a reply to Byzantine officials:

Nikephoros pointed out to Liutprand personally that Otto was a mere barbarian king who had no right to call himself an emperor, nor to call himself a Roman. Just before Liutprand's arrival in Constantinople, Nikephoros II had received an offensive letter from Pope John XIII

Pope John XIII ( la, Ioannes XIII; died 6 September 972) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 1 October 965 to his death. His pontificate was caught up in the continuing conflict between the Holy Roman emperor, Otto I, and t ...

, possibly written under pressure from Otto, in which the Byzantine emperor was referred to as the "Emperor of the Greeks" and not the "Emperor of the Romans", denying his true imperial status. Liutprand recorded the outburst of Nikephoros's representatives at this letter, which illustrates that the Byzantines too had developed an idea similar to ''translatio imperii'' regarding the transfer of power from Rome to Constantinople:

Liutprand attempted to diplomatically excuse the pope by stating that the pope had believed that the Byzantines would not like the term "Romans" since they had moved to Constantinople and changed their customs and assured Nikephoros that in the future, the eastern emperors would be addressed in papal letters as "the great and august emperor of the Romans". Otto's attempted cordial relations with the Byzantine Empire would be hindered by the problem of the two emperors, and the eastern emperors were less than eager to reciprocate his feelings. Liutprand's mission to Constantinople was a diplomatic disaster, and his visit saw Nikephoros repeatedly threaten to invade Italy, restore Rome to Byzantine control and on one occasion even threaten to invade Germany itself, stating (concerning Otto) that "we will arouse all the nations against him; and we will break him in pieces like a potter's vessel". Otto's attempt at a marriage alliance would not materialize until after Nikephoros's death. In 972, in the reign of Byzantine emperor John I Tzimiskes

John I Tzimiskes (; 925 – 10 January 976) was the senior Byzantine emperor from 969 to 976. An intuitive and successful general, he strengthened the Empire and expanded its borders during his short reign.

Background

John I Tzimiskes ...

, a marriage was secured between Otto's son and co-emperor Otto II

Otto II (955 – 7 December 983), called the Red (''der Rote''), was Holy Roman Emperor from 973 until his death in 983. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto II was the youngest and sole surviving son of Otto the Great and Adelaide of Italy ...

and John's niece Theophanu

Theophanu (; also ''Theophania'', ''Theophana'', or ''Theophano''; Medieval Greek ; AD 955 15 June 991) was empress of the Holy Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Otto II, and regent of the Empire during the minority of their son, Emperor O ...

.

Though Emperor Otto I briefly used the title ''imperator augustus Romanorum ac Francorum'' ("august emperor of Romans and Franks") in 966, the style he used most commonly was simply ''Imperator Augustus''. Otto leaving out any mention of Romans in his imperial title may be because he wanted to achieve the recognition of the Byzantine emperor. Following Otto's reign, mentions of the Romans in the imperial title became more common. In the 11th century, the German king (the title held by those who were later crowned emperors) was referred to as the ''rex Romanorum'' ("king of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

") and in the century after that, the standard imperial title was ''dei gratia Romanorum Imperator semper Augustus'' ("by the Grace of God, emperor of the Romans, ever august").

Hohenstaufen period

To Liutprand of Cremona and later scholars in the west, the perceived weak and degenerate eastern emperors were not true emperors; there was a single empire under the true emperors (Otto I and his successors), who demonstrated their right to the empire through their restoration of the Church. In return, the eastern emperors did not recognize the imperial status of their challengers in the west. Although Michael I had referred to Charlemagne by the title ''Basileus'' in 812, he hadn't referred to him as the ''Roman'' emperor. ''Basileus'' in of itself was far from an equal title to that of Roman emperor. In their own documents, the only emperor recognized by the Byzantines was their own ruler, the Emperor of the Romans. InAnna Komnene

Anna Komnene ( gr, Ἄννα Κομνηνή, Ánna Komnēnḗ; 1 December 1083 – 1153), commonly Latinized as Anna Comnena, was a Byzantine princess and author of the ''Alexiad'', an account of the reign of her father, the Byzantine emperor, ...

's ''The Alexiad

The ''Alexiad'' ( el, Ἀλεξιάς, Alexias) is a medieval historical and biographical text written around the year 1148, by the Byzantine princess Anna Komnene, daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. It was written in a form of artificial ...

'' (), the Emperor of the Romans is her father, Alexios I

Alexios I Komnenos ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός, 1057 – 15 August 1118; Latinized Alexius I Comnenus) was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during ...

, while the Holy Roman emperor Henry IV is titled simply as the "King of Germany".

In the 1150s, the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos ( el, Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, translit=Manouíl Komnenos, translit-std=ISO; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos (; " born in the purple"), was a Byzantine empero ...

became involved in a three-way struggle between himself, the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt o ...

and the Italo-Norman

The Italo-Normans ( it, Italo-Normanni), or Siculo-Normans (''Siculo-Normanni'') when referring to Sicily and Southern Italy, are the Italian-born descendants of the first Norman conquerors to travel to southern Italy in the first half of th ...

King of Sicily

The monarchs of Sicily ruled from the establishment of the County of Sicily in 1071 until the "perfect fusion" in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1816.

The origins of the Sicilian monarchy lie in the Norman conquest of southern Italy which occ ...

, Roger II

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became Duke of Apulia and Calabria in ...

. Manuel aspired to lessen the influence of his two rivals and at the same time win the recognition of the Pope (and thus by extension Western Europe) as the sole legitimate emperor, which would unite Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

under his sway. Manuel reached for this ambitious goal by financing a league of Lombard towns to rebel against Frederick and encouraging dissident Norman barons to do the same against the Sicilian king. Manuel even dispatched his army to southern Italy, the last time a Byzantine army ever set foot in Western Europe. Despite his efforts, Manuel's campaign ended in failure and he won little except the hatred of both Barbarossa and Roger, who by the time the campaign concluded had allied with each other.

Frederick Barbarossa's crusade

Soon after the conclusion of the Byzantine–Norman wars in 1185, the Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos received word that aThird Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

had been called due to Sultan Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

's 1187 conquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, ...

of Jerusalem. Isaac learnt that Barbarossa, a known foe of his empire, was to lead a large contingent in the footprints of the First and Second crusades through the Byzantine Empire. Isaac II interpreted Barbarossa's march through his empire as a threat and considered it inconceivable that Barbarossa did not also intend to overthrow the Byzantine Empire. As a result of his fears, Isaac II imprisoned numerous Latin citizens in Constantinople. In his treaties and negotiations with Barbarossa (which exist preserved as written documents), Isaac II was insincere as he had secretly allied with Saladin to gain concessions in the Holy Land and had agreed to delay and destroy the German army.

Barbarossa, who did not in fact intend to take Constantinople, was unaware of Isaac's alliance with Saladin but still wary of the rival emperor. As such he sent out an embassy in early 1189, headed by the Bishop of Münster. Isaac was absent at the time, putting down a revolt in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, and returned to Constantinople a week after the German embassy arrived, after which he immediately had the Germans imprisoned. This imprisonment was partly motivated by Isaac wanting to possess German hostages, but more importantly, an embassy from Saladin, probably noticed by the German ambassadors, was also in the capital at this time.

On 28 June 1189, Barbarossa's crusade reached the Byzantine borders, the first time a Holy Roman emperor personally set foot within the borders of the Byzantine Empire. Although Barbarossa's army was received by the closest major governor, the governor of Branitchevo, the governor had received orders to stall or, if possible, destroy the German army. On his way to the city of Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names in other languages) is the third largest city in Serbia and the administrative center of the Nišava District. It is located in southern part of Serbia. , the city proper has a population of 183,164, whi ...

, Barbarossa was repeatedly assaulted by locals under the orders of the governor of Branitchevo and Isaac II also engaged in a campaign of closing roads and destroying foragers. The attacks against Barbarossa amounted to little and only resulted in around a hundred losses. A more serious issue was a lack of supplies, since the Byzantines refused to provide markets for the German army. The lack of markets was excused by Isaac as due to not having received advance notice of Barbarossa's arrival, a claim rejected by Barbarossa, who saw the embassy he had sent earlier as notice enough. Despite these issues, Barbarossa still apparently believed that Isaac was not hostile against him and refused invitations from the enemies of the Byzantines to join an alliance against them. While at Niš he was assured by Byzantine ambassadors that though there was a significant Byzantine army assembled near Sofia, it had been assembled to fight the Serbs and not the Germans. This was a lie, and when the Germans reached the position of this army, they were treated with hostility, though the Byzantines fled at the first charge of the German cavalry.

Isaac II panicked and issued contradictory orders to the governor of the city of Philippopolis, one of the strongest fortresses in

Isaac II panicked and issued contradictory orders to the governor of the city of Philippopolis, one of the strongest fortresses in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

. Fearing that the Germans were to use the city as a base of operations, its governor, Niketas Choniates

Niketas or Nicetas Choniates ( el, Νικήτας Χωνιάτης; c. 1155 – 1217), whose actual surname was Akominatos (Ἀκομινάτος), was a Byzantine Greek government official and historian – like his brother Michael Akominatos, w ...