Populares on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Optimates (;

References to ''populares'' in scholarship today "do not imply a co-ordinated 'party' with a distinctive ideological character, a kind of political grouping for which there is no evidence in Rome, but simply allude to a... type of senator" who is "at least at that moment acting as the people's man". This is in contrast to the 19th century view of the ''populares'' from Mommsen, in which they are a group of aristocrats which supported democracy and the rights and material interests of the common people.

The highly influential view of Christian Meier redefined the ''popularis'' as a label for a senator using the popular assemblies' law-making powers to overrule decisions of the senate, primarily as a political tactic to get ahead in Roman politics. In this view, a ''populares'' politician is a person who:

References to ''populares'' in scholarship today "do not imply a co-ordinated 'party' with a distinctive ideological character, a kind of political grouping for which there is no evidence in Rome, but simply allude to a... type of senator" who is "at least at that moment acting as the people's man". This is in contrast to the 19th century view of the ''populares'' from Mommsen, in which they are a group of aristocrats which supported democracy and the rights and material interests of the common people.

The highly influential view of Christian Meier redefined the ''popularis'' as a label for a senator using the popular assemblies' law-making powers to overrule decisions of the senate, primarily as a political tactic to get ahead in Roman politics. In this view, a ''populares'' politician is a person who:

The traditional view comes from scholarship by

The traditional view comes from scholarship by

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "best ones", ) and populares (; Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "supporters of the people", ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

. There is "heated academic discussion" as to whether Romans would have recognised an ideological content or political split in the label.

Among other things, ''optimates'' have been seen as supporters of the continued authority of the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, politicians who operated mostly in the senate, or opponents of the ''populares''. The ''populares'' have also been seen as focusing on operating before the popular assemblies, generally in opposition to the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, using "the populace, rather than the senate, as a means or advantage

Or or OR may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* "O.R.", a 1974 episode of M*A*S*H

* Or (My Treasure), a 2004 movie from Israel (''Or'' means "light" in Hebrew)

Music

* ''Or'' (album), a 2002 album by Golden Boy with Miss ...

.

References to optimates (also called ''boni'', "good men") and ''populares'' are found among the writings of Roman authors of the 1st century BC. The distinction between the terms is most clearly established in Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

's ''Pro Sestio'', a speech given and published in 56 BC, where he framed the two labels against each other.

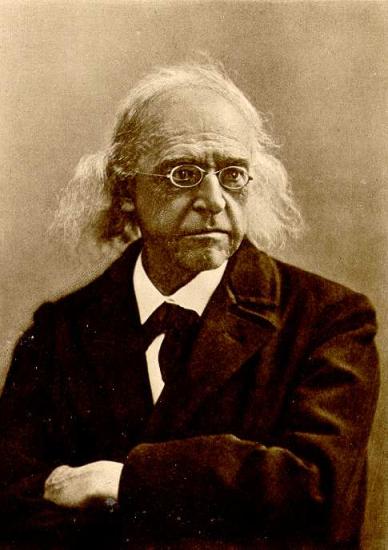

With the publication of the ''Römische Geschichte'' in the 1850s, the German historian Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centur ...

set the enduring and popular interpretation that ''optimates'' and ''populares'' represented political parties, which he implicitly compared to the German liberal and conservative parties of his own day. Mommsen's paradigm, however, has been criticised by generations of historians, first by Friedrich Münzer

Friedrich Münzer (22 April 1868 – 20 October 1942) was a German classical scholar noted for the development of prosopography, particularly for his demonstrations of how family relationships in ancient Rome connected to political struggles. He ...

, followed by Ronald Syme, who considered that Roman politics was marked by familial and individual ambitions, not parties. Other historians have pointed the impossibility to apply such labels on many individuals, who could pretend to be ''popularis'' or ''optimas'' as they saw fit; the careers of Drusus

Drusus may refer to:

* Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Drusus) (10 BC–AD 54), Roman emperor from 41 to 54

* Drusus Caesar (AD 8–33), adoptive grandson of Roman emperor Tiberius

* Drusus Julius Caesar (14 BC–AD 23), son of Roman emperor Tiberius

...

or Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

are for example impossible to fit into one "party". Ancient usage was also far from clear: even Cicero, while linking ''optimates'' to Greek ''aristokratia'' (''ἀριστοκρατία''), also used the word ''populares'' to describe politics "completely compatible with... honourable aristocratic behaviour".

As a result, modern historians do not recognise any "coherent political party" under either ''populares'' or ''optimates'', nor do those labels lend themselves easily to comparison with a modern left-right split. Democratic interpretations of Roman politics, however, have pushed for a re-evaluation which attributes an ideological tendency – e.g. ''populares'' believing in popular sovereignty – to the labels.

Meaning

With the publication of the ''Römische Geschichte'' in the 1850s, the German historianTheodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centur ...

set the enduring and popular interpretation that ''optimates'' and ''populares'' represented aristocratic and democratic parliamentary-style political parties, with the labels emerging around the time of the Gracchi. His interpretation "owe much to nineteenth century German liberal thought". Classicists today, however, generally agree that neither ''optimate'' or ''popularis'' referred to political parties: "It is common knowledge nowadays that ''populares'' did not constitute a coherent political group or 'party' (even less so than their counterparts, '' optimates'')".

Unlike in modern times, Roman politicians stood for office the basis of their personal reputations and qualities rather than with a party manifesto or platform. For example, the opposition to the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many ve ...

failed to act as a united front with coherent coordination of its members, acting instead on an ad hoc basis with regular defections to and from those opposing the political alliance depending on the topic of debate, personal relations, etc. These ad hoc alliances and many different methods of gaining political influence meant were no "neat categories of ''optimates'' and ''populares''" or of conservatives and radicals in a modern sense. Erich S Gruen, for example, in ''Last Generation of the Roman Republic'' (1974) rejected both ''populares'' and ''optimates'', saying "such labels obscure rather than enlighten" and arguing that ''optimates'' was used not as a political label, but instead used to praise a member of the political elite.

Moving away from the 19th century view of political parties or factions vying for dominance, the scope of the modern academic debate focuses on whether the terms referred to an ideological split among aristocrats or whether the terms were meaningless or topics of debate themselves.

''Optimates''

The traditional view of the ''optimates'' refers to aristocrats who defended their own material and political interests and behaved akin to modern fiscal conservatives in opposing wealth redistribution and supporting small government. To that end, the ''optimates'' were viewed traditionally as emphasising the authority or influence of the senate over other organs of the states, including the popular assemblies. In other instances, the ''optimates'' are defined "somewhat mechanically, as those who opposed the ''populares''". This definition relying on a "senatorial" party or fiscal conservatives breaks down at a closer reading of the evidence. A "senatorial" party describes no meaningful split, as basically all active politicians were senators. A definition to the terms based on whether a politician supported land redistribution or grain subsidies runs into two issues. Such measures were not "the sole preserve of the so-called populares" and "were not per se incompatible with traditional senatorial policy, given the extensive colonisation the senate had overseen in the past and the grain provision which members of the elite occasionally organised on a private basis". Moreover, identifying the ''populares'' based on the policies they supported in office would place politicians traditionally identified as belonging to one "faction" into the "opposite" camp: *Publius Sulpicius Rufus

Publius Sulpicius Rufus (124–88 BC) was a Roman politician and orator whose attempts to pass controversial laws with the help of mob violence helped trigger the first civil war of the Roman Republic. His actions kindled the deadly rivalry bet ...

, one of the classic ''populares'', supported policies that had little "to do with the betterment of the ''populus'' and in fact appear to have been distinctly unpopular".

* Marcus Livius Drusus, brought agrarian reform laws with the support of the senate, giving his policies a ''popularis'' tone, even when senatorial support and agrarian reforms are supposedly dichotomous.

* Cato the Younger, traditionally identified as ''the'' ''optimate'', becomes ''popularis'' for supporting expansion of the grain dole during his tribunate

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the ...

.

* Sulla, traditionally identified also as an arch-conservative, turns ''popularis'' for "probably confiscat ngand redistribut ngmore land in Italy than any other Roman politician".

* And Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, traditionally seen as ''popularis'' (though never self-identifying with that label in his extant texts), emerges as an ''optimate'' for "substantially reduc ngthe number of grain recipients in Rome during his dictatorship".

Other proposed views of ''optimates'' are that they were leaders of the senate or those acting with the support of the senate. Mouritsen in ''Politics in the Roman Republic'' (2017) rejects both of the traditional definitions. Of ''optimates'' being those with the support of the senate:

Usage of the term by contemporaries also was not highly dichotomised. ''Optimate'' was used generically to refer to the wealthy classes in Rome as well as the aristocracies of foreign cities or states:

''Populares''

References to ''populares'' in scholarship today "do not imply a co-ordinated 'party' with a distinctive ideological character, a kind of political grouping for which there is no evidence in Rome, but simply allude to a... type of senator" who is "at least at that moment acting as the people's man". This is in contrast to the 19th century view of the ''populares'' from Mommsen, in which they are a group of aristocrats which supported democracy and the rights and material interests of the common people.

The highly influential view of Christian Meier redefined the ''popularis'' as a label for a senator using the popular assemblies' law-making powers to overrule decisions of the senate, primarily as a political tactic to get ahead in Roman politics. In this view, a ''populares'' politician is a person who:

References to ''populares'' in scholarship today "do not imply a co-ordinated 'party' with a distinctive ideological character, a kind of political grouping for which there is no evidence in Rome, but simply allude to a... type of senator" who is "at least at that moment acting as the people's man". This is in contrast to the 19th century view of the ''populares'' from Mommsen, in which they are a group of aristocrats which supported democracy and the rights and material interests of the common people.

The highly influential view of Christian Meier redefined the ''popularis'' as a label for a senator using the popular assemblies' law-making powers to overrule decisions of the senate, primarily as a political tactic to get ahead in Roman politics. In this view, a ''populares'' politician is a person who:

doptsa certain method of political working, to use the populace, rather than the senate, as a means to an end; the end being, most likely, personal advantage for the politician concerned.

''Ratio popularis''

The ''ratio popularis'', or strategy of putting political questions before the people writ large, was pursued when politicians were unable to achieve their goals through the normal process in the senate. This was in part structural: the "dyadic nature of he senate and people of Rome, ie the republicmeant that when a senator opposed his peers... there was only recourse available" to the people. This political method involved a populist style of rhetoric, and "only to a limited extent, that of policy" with even less ideological content. The content of ''popularis'' legislation was tied to the fact that politicians choosing to go before the people required needed strong support therefrom to overrule the decision of the senate. This forced politicians choosing a popular strategy to include policies that directly benefited voters in the assemblies, such as land redistribution and grain doles. The earlier ''popularis'' tactics of Tiberius Gracchus reflected the dominance of rural voters who had resettled to Rome recently, while the later ''popularis'' tactics of Clodius reflected the interests of the masses of urban poor. Material interests like corn subsidy bills were not the whole of ''popularis'' causes: ''popularis'' politicians also may have made arguments on the proper role of the Assemblies in the Roman state (ie, a popular sovereignty) rather than just questions of material interests. Other benefits proposed attempted to empower supporters in the popular assemblies, with introduction of secret ballot, restoration of tribunician rights after Sulla's dictatorship, promotion of non-senators onto juries before the law courts, and the general election of priests. All of these empowered non-senatorial supporters broadly, including both the wealthy '' equites'' and the poor urban population in Rome.Ideological view

One of the larger issues in modern scholarship is whether the politicians who operated in the ''ratio popularis'' actually believed in their proposals, scepticism of which "certainly seems well warranted in many cases". A democratic interpretation of Roman politics neatly complements an ideological revival by interpreting Roman politicians to vie for popular support at an ideological, but not factional, level. This link, however, remains tenuous, as "candidates apparently never ran on specific policies or associated themselves with particular ideologies during their campaign . Moreover, speculation as to the inner motivations of Roman politicians cannot be substantiated one way or the other, as the inner thoughts of the Roman elite are almost entirely lost. Even the apparent deaths suffered by "''popularis''" tribunes cannot be accepted at face value: initial intentions are not final outcomes, it is unlikely that those who followed a ''popularis'' path expected death. Mackie argued that ''popularis'' politicians had an ideological bent towards criticising the senate's legitimacy, focusing on the sovereign powers of the popular assemblies, criticising the senate for neglecting common interests, and accusing the senate of administering the state corruptly. She added that ''populares'' advocated for the popular assemblies to take control of the republic, phrasing demands in terms of ''libertas'', referring to popular sovereignty and the power of the Roman assemblies to create law. T. P. Wiseman argues, further, that these differences reflected "rival ideologies" with "mutually incompatible iews onwhat the republic was". This democratic interpretation did not imply a party structure, instead focusing on motivations and policies. Scholars of the late republic have not reached a consensus as to whether Roman politicians really were divided in these terms. Nor does an ideological approach explain the traditional identification of certain politicians (egPublius Sulpicius Rufus

Publius Sulpicius Rufus (124–88 BC) was a Roman politician and orator whose attempts to pass controversial laws with the help of mob violence helped trigger the first civil war of the Roman Republic. His actions kindled the deadly rivalry bet ...

) as ''popularis'' when the policies they advanced were only weakly connected to the welfare of the Roman voter. Robb argues, moreover, that the premise of the label, ie that a certain person or policy benefits the people write large, is of little use: "the principle of acting in the popular interest was a central one that all politicians would claim to be following".

In rhetoric

The "constitutional framework in which politicians operated automatically turned policy disagreements into rhetorical contests between ''populus'' and aristocracy": tribunes which were unable to secure the support of their peers in the senate would naturally go before the people; to justify this they turned to stock arguments for popular sovereignty; opponents would then bring out similar stock arguments for senatorial authority. Young Roman politicians also turned regularly to controversial rhetoric or policies in an attempt to build their name recognition and stand out from the mass of other political candidates in their short one-year terms, with few apparent negative impacts on their longer-term career prospects. ''Popularis'' rhetoric was couched "in terms of the consensus of values at Rome at the time: ''libertas'', ''leges'', ''mos maiorum'', and senatorial incompetence at governing the ''res publica''". In public speeches during the republic, legislative disagreements did not emerge in party-political terms: "from the rostra... neither the opponents of Tiberius Gracchus, nor Catulus against Gabinius, nor Bibulus against Caesar, nor Cato against Trebonius even so much as suggested that their advice to the was predicated on an 'optimate' policy based on a different arrangement of political ends and means from those of the 'popular' advocates of a bill... there was, it seems, virtually no place on the rostra for ideological bifurcation". For the Roman in the street, political debate was not related to party affiliations, but the issue and proposer itself: "Is the proposer of this agrarian (or frumentary, etc.) law really championing our interests, as he avows, or is he rather pursuing some private benefit for himself or something else behind the scenes?" which naturally flowed into the themes of personal credibility that recur in republican public rhetoric. Like most Roman rhetoric, ''popularis'' rhetoric also drew heavily on historical precedents (''exempla'') – including that from ancient times, such as the revival of the ''comitia Centuriata'' as a popular law court, – from the abolition of the Roman monarchy to the popular rights and liberties won by the secession of the plebs. ''Popularis'' rhetoric surrounding secret ballots and land reform were not framed in terms of innovations, but rather, in terms of preserving and restoring the birth-right liberty of the citizenry. And ''populares'' too could hijack traditionally ''optimate'' themes by criticising ''current'' senators for failing to live up to the examples of their ancestors, acting in ways which would in the long run harm the authority of the senate, or framing their own arguments in fiscal responsibility. Both putative groups agreed on core values such as Roman liberty and the fundamental sovereignty of the Roman people; even those who were supporting the senate at some time or another would not be able to wholly discount the traditional sovereignty attributed to the people. Furthermore, much of the perceived difference between ''optimates'' and ''populares'' emerged from rhetorical flourishes unsupported by policy: "no matter how emphatically the people’s interests and 'sovereignty' may have been asserted, the republic never saw any concrete attempts to change the nature of Roman society or shift the balance of power".Usage by ancient Romans

Beyond the modern usage of the two terms in classical studies to refer to the putative political parties, the terms also emerge from the Latin literature of the period. InLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, the word ''popularis'', is normally used outside the works of Cicero to mean "compatriot" or "fellow citizen". The word also could be used pejoratively to refer to populists or politicians pandering to the people, politicians with great personal popularity, politicians who were ostensibly acting in the peoples' interest, and actions before crowds of the people.

The word ''optimates'', while infrequent in the surviving canon, is also used to refer to aristocrats or the aristocracy as a whole.

Cicero

In Cicero's letters – rather than his forensic speeches – he used it generally to refer to popularity. In Cicero's philosophical works, it was used to refer to "the majority of the people" and to describe "the style of speech most useful for public speaking". The oppositional meaning between ''populares'' and ''optimates'' emerges mainly fromCicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

's drawing of a distinction between the two in his speech ''Pro Sestio'', a speech made to defend a friend instrumental in recalling Cicero from exile by his political enemy Clodius. Cicero's use of the term, that "''populares'' aim to please the multitude", is recognised to be polemical. His remarks that ''popularis'' tactics emerged from a failure to win the support of the senate and of personal grievances with the senate are also "equally suspect". Cicero's usage in that speech draws a distinction between ''optimates'' who "are honourable, honest, and upright... ndsafeguard the interests of the state and the liberty of its citizens" with ''populares'' who are not so honourable and instead engage in failed attempts to cultivate demagoguery. Cicero's description of Clodius as ''popularis'' "concentrates on the demagogic sense of the word, rather than risking attack on the rights of the people".

Mouritsen writes of Cicero in ''Pro Sestio'':

Cicero’s bold rhetorical self-reinvention in the ''Pro Sestio'' has presented historians with a deceptively simple model which at first sight seems to provide a key to unlocking the secrets of Roman politics. But the terminology Cicero uses turns out to be unique and unlike anything else found in the ancient sources... We are therefore not dealing with an observable phenomenon for which the ''Pro Sestio'' happens to offer a convenient label. Rather, it is the other way round: Cicero’s use of ''popularis'' in that particular speech has reified what would otherwise have remained discrete difficult-to-classify events and individuals and turned them into manifestations of a single political movement.Cicero, however, did not always use the word this way. During his consulship, he "stak dhis own claim to being ''popularis'' nthe popular mandate he eldas an elected consul" and drew a distinction between himself and other politicians as to who truly acted in the interests of the Roman people. This usage did not draw a contrast between ''populares'' and ''optimates''. He similarly uses the term ''popularis'' describe himself in the Seventh Phillipic for his opposition to Antony and later, in the Eighth Phillipic, to describe the actions of Nasica and Opimius "for having acted in the public interests" by killing Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus. This usage also does not contrast to ''optimates'' but instead suggests that some person is "truly acting in the interest of the people".

Sallust

Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (; 86 – ), was a Roman historian and politician from an Italian plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became during the 50s BC a partisa ...

, a Roman politician who served as praetor during Caesar's dictatorship, writing an account of the Catiline conspiracy

The Catilinarian conspiracy (sometimes Second Catilinarian conspiracy) was an attempted coup d'état by Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catiline) to overthrow the Roman consuls of 63 BC – Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida – a ...

and the Jugurthine war, does not use the word ''optimas'' (or ''optimates'') at all, and uses the word ''popularis'' only ten times. None of those usages are political, referring either to countrymen or comrades. Robb speculates that " allustmay have chosen the avoid using the word precisely because it was so imprecise and did not clearly identify a particular kind of politician".

In his work on the Jugurthine war, he does have a narrative of two parties: one of the people (''populus'') and one the nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

(''nobilitas''), where a small and corrupt section of the senate () is contrasted oligarchically against the rest of society. But because the ''nobiles'' were defined not by their ideology, but by their ancestry from past holders of curule magistracies, these are not the ''optimates'' of ideological or political-party conflict, who are themselves "riven by internal divisions".

Sallust also fails to draw any distinction between popular sovereignty and senatorial prestige as sources of legitimacy or authority. He also gives the "dissenting nobles and their factions" no labels, "for the simple reason that they lacked the common characteristics which would have enabled such a categorisation", instead presenting a cynical view in which Roman politicians cloaked themselves opportunistically in terms of ''libertas populi Romani'' and ''senatus auctoritas'' as means for self-advancement.

Other people in the late republic

While ancient accounts of the late republic describe "a political 'establishment' and the opposition" thereto they do not use words such as ''populares'' to describe that opposition. Because politicians viewed their own status as reflected by the support of the people, the latter acting passively as a judge of "aristocratic merit", all politicians claimed "to be 'acting in the interest of the people', or in other words, ''popularis''". Words used to describe dissent in the vein of Gaius Gracchus andQuintus Varius Severus Quintus Varius Severus (from 125 to 120 BC; died after 90 BC) was a politician in the late Roman Republic. He was also called Hybrida (of mixed race) because his mother was Spanish.Harry Thurston Peck ''Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities'' ...

trended more towards ''seditio'' and ''seditiosus''.

The works of Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, the author of '' Ab Urbe Condita Libri'' (known in English as the ''History of Rome''), have been used to argue in favour of a distinction between ''populares'' and ''optimates'' through to earlier periods such as the Conflict of the Orders

The Conflict of the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the pl ...

. Livy wrote after the late republic, during the Augustan period. However, his treatment of the late Republic does not survive except in an epitome called the Periochae

The work called ( en, From the Founding of the City), sometimes referred to as (''Books from the Founding of the City''), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by Livy, a Roman historian. The work ...

. While it is generally accepted that "Livy applies late republican political language to events from earlier periods", the terms ''optimates'' and ''populares'' (and derivatives) appear infrequently and generally not in a political context.

The vast majority of the usages of ''popularis'' in Livy denote fellow citizens, comrades, and oratory suitable for public speaking. Usage of ''optimates'' is also infrequent, the majority of usages referring to foreign aristocrats. Livy's terminology in describing the conflict of the orders referred not to ''populares'' and ''optimates'' but rather to plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words " commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins ...

and patricians and their place in the constitutional order. Livy only uses the word ''popularis'' in contrast to ''optimates'' in political terms only once, in a speech put into the mouth of Barbatus on the tyranny of the Second Decemvirate in the 450s BC, centuries before the late republic.

Historiography

The traditional view comes from scholarship by

The traditional view comes from scholarship by Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centur ...

during the 19th century, in which he identified both ''populares'' and ''optimates'' as modern "parliamentary-style political parties", suggesting that the conflict of the orders

The Conflict of the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the pl ...

resulted in the formation of an aristocratic and a democratic party. For example, John Edwin Sandys, writing 1920 in this traditional scholarship, identified the ''optimates'' – qua party – as the killers of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC. Mommsen too suggested that the labels themselves became common in Gracchan times.

This view was re-evaluated, starting with Gelzer's ''Die Nobilität de Römischen Republik'', with a model of Roman politics in which a candidate "could not rely on the support of an organised party but instead had to cultivate a wide range of personal relationships extending both upwards and downwards in society". In later work, he returned to a more ideological interpretation of ''popularis'', but viewed ''popularis'' politicians not as democrats, but as demagogues "more concerned about gaining the authority of the people for their plans than implementing heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offic ...

will".

By the 1930s, a far less ideological interpretation emerged, viewing Roman republican politics as dominated by parties, not of like-minded ideologues, but of aristocratic ''gentes''. Syme in the 1939 book ''Roman Revolution'' wrote that:

The political life of the Roman Republic was stamped and swayed, not by parties and programmes of a modern and parliamentary character, not by the ostensible opposition between senate and people, ''optimates'' and ''populares'', ''nobiles'' and ''novi homines'', but by the strife for power, wealth and glory. The contestants were the ''nobiles'' among themselves, as individuals or in groups, open in the elections and in the courts of law, or masked by secret intrigue.Syme's description of Roman politics viewed the late republic "as a conflict between a dominant oligarchy drawn from a set of powerful families and their opponents" which operated primarily not in ideological terms, but in terms of feuds between family-based factions. Strausberger, writing also in 1939, challenged the traditional view of political parties, arguing that "there was no 'class war'" in the various civil wars (eg Sulla's civil war and

Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was one of the last politico-military conflicts of the Roman Republic before its reorganization into the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations between Gaius Julius Caesar an ...

) that started the collapse of the republic.

Meier noted in 1965 that "'popular' politics was very difficult both to understand and describe notingthat the people itself had no political initiative but was 'directed' by the aristocratic magistrates it elected meaning that'popular' politics was... the province of politicians not the people". Moreover, "very few 'populares' appeared to embrace long term goals and most acted in a way described as ''popularis'' for only a short time".

He suggested four meanings for the word ''popularis'':

# politicians acting as champions of the people against the senate,

# politicians manipulating the popular assemblies,

# politicians who took up a ''causa populi'' and paraded the people before the ''plebs urbana'', and

# a manner adopted by politicians who used "popular" means to prolong a political career.

His analysis viewed ''popularis'' in terms of a method "adopted by those who opposed the senatorial majority, rovidinga behavioural model which did not concern itself with attributing motive to political action". Gruen in the famous ''Last Generation of the Roman Republic'' in 1974 rejected the terms entirely:

Brunt, writing in the 1980s–90s, took a view trending against political parties but towards an ideological dimension. He emphasised that shifting alliances and loyalties between senators precluded the existence of "durable or cohesive political factions" which could be identified as ''optimates'' or ''populares'' and that "optimates and populares did not and could not constitute parties as we know them". Moreover, he argued there were no "large groups of politicians, bound together by ties of kinship or friendship, or by fidelity to a leader, who ctedtogether consistently for any considerable time" and that "of large, cohesive, and durable coalitions of families there is no evidence at all for any period". Instead, he argued that the distinction was not one of permanent factional strife, but rather, of support and opposition of the senate: ''popularis'' politicians, while not being "reformers" per se, would resort to the popular assemblies if they felt intervention from the people was desirable, with an ideological distinction dividing Roman politicians as to what was in the public interest.

The ''optimates'' were explored by Burckhardt in 1988, viewing them as portions of the nobility acting to advance laws against corruption, electoral bribery, and overly flagrant displays of wealth (ie laws on ''repetundae'', ''ambitus'', and ''sumptuaria'') with tactics such as vetoes and obstructionism. Gruen, however, noted in 1995, that this analysis provided "no clear criteria" for determining anything about the makeup, size, or organisation of the group. Identification of ''optimates'' also continues to be difficult. They have been identified as "members of an 'aristocratic party' to upholders of senatorial authority to supporters of the class interests of the wealthy".

Mackie argued in a 1992 influential paper revitalising the ideological view that ''ratio popularis'' implied and required substantial argumentation based on Roman tradition to justify the intervention of the popular assemblies. Such argumentation took the form of an ideology of popular sovereignty, self-justifying the leadership of the comitia in the state. Hölkeskamp suggested in 1997 that ''popularis'' ideology reflected a history of senatorial intransigence characterised as "partial and unlawful" which, over time, eroded the legitimacy of the senate in the republic. Morstein-Marx's book on mass oratory in the republic – often before ''contiones'' or assemblies of the people – focused, however, on how both opponents and supporters of legislation attempted to portray themselves as "true" ''popularis'' acting in the interest of the people and the other as demagoguery.

There continues to be debate as to the utility of the terms in scholarship. In 1994, Andrew Lintott wrote in ''The Cambridge Ancient History'' that although both factions came from the same social class, there is "no reason to deny the divergence of ideology highlighted by Cicero" with themes and leaders stretching back in Cicero's time for hundreds of years.

T. P. Wiseman similarly lamented an "ideological vacuum" in 2009, promoting the term as a label for ideology rather than for political factionalism in the vein of Mommsen.

Other recent publications have continued to contest the topic. M. A. Robb argued in her 2010 book ''Beyond Populares and Optimates'' that the labels emerge from Cicero's writings and were "far from corresponding with definite parties or definite policies". It seems Romans did not use the terms themselves: for example, Caesar and Sallust never identified ''Caesar'' as a member of any ''populares'' "faction". "The terms ''populares'' and ''optimates'' were not common and everyday labels used to categorise certain types of late republican politician". Robb rejects usage of both ''populares'' and ''optimates'' writ large, as all Roman politicians would have asserted their devotion to public liberty and also have asserted their own excellence; instead of ''populares'' to describe demagoguery, Romans would have used ''seditiosi''. Similarly, Henrik Mouritsen, writing in the 2017 book ''Politics in the Roman Republic'' rejects the putative categories entirely, supporting a "politics without 'parties'" in the vein of Meier, where politicians "at certain moments in their career used their powers without the backing of their peers".

Notes

References

Footnotes Books * * * * * * * * * Articles * * *Further reading

* * * * * {{refend Roman Republic Society of ancient Rome