nuclear espionage on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nuclear espionage is the purposeful giving of state secrets regarding

The ways of committing espionage have multiplied with the increase dependence on technology. This venerability is where a nation like Iran can benefit. They have one of the world's best cyber arsenals, and it only continues to grow. This allows them to perform cyberattacks much like

The ways of committing espionage have multiplied with the increase dependence on technology. This venerability is where a nation like Iran can benefit. They have one of the world's best cyber arsenals, and it only continues to grow. This allows them to perform cyberattacks much like

India was involved with assisting espionage between the

India was involved with assisting espionage between the

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s to other states without authorization (espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

). There have been many cases of known nuclear espionage throughout the history of nuclear weapons and many cases of suspected or alleged espionage. Because nuclear weapons are generally considered one of the most important of state secrets, all nations with nuclear weapons have strict restrictions against the giving of information relating to nuclear weapon design

Nuclear weapons design are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

# Pure fission weapons are the simplest, least technically de ...

, stockpiles, delivery systems, and deployment. States are also limited in their ability to make public the information regarding nuclear weapons by non-proliferation agreements.

Soviet spies in the Manhattan Project

During theManhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, the joint effort during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

by the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

to create the first nuclear weapons, there were many instances of nuclear espionage in which project scientists or technicians channeled information about bomb development and design

A design is the concept or proposal for an object, process, or system. The word ''design'' refers to something that is or has been intentionally created by a thinking agent, and is sometimes used to refer to the inherent nature of something ...

to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. These people are often referred to as the Atomic Spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold W ...

, and their work continued into the early Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Because most of these cases became well known in the context of the anti-Communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

1950s, there has been long-standing dispute over the exact details of these cases, though some of this was settled with the making public of the Venona project transcripts, which were intercepted and decrypted messages between Soviet agents and the Soviet government. Some issues remain unsettled, however.

The most prominent of these included:

*Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British, and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly a ...

– German refugee theoretical physicist who worked with the British delegation at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

. He was eventually discovered, confessed, and sentenced to jail in Britain. He was later released, and he emigrated to East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

. Because of his close connection to many aspects of project activities, and his extensive technical knowledge, he is considered to have been the most valuable of the "Atomic Spies" in terms of the information he gave to the Soviet Union about the American fission bomb program. He also gave early information about the American hydrogen bomb program but since he was not present at the time that the successful Teller-Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

was discovered, his information on this is not thought to have been of much value.

* Theodore Hall – a young American physicist at Los Alamos, whose identity as a spy was not revealed until very late in the 20th century. He gave implosion bomb details to a Soviet official at a U.S. Communist party meeting in New York. From then, he continued to give information about the hydrogen bomb to his Soviet contacts. He was never arrested in connection to his espionage work, though seems to have admitted to it in later years to reporters and to his family. Near the end of his life, he admitted that he abhorred the idea of the United States holding overwhelming power over the world's nuclear stockpile and believed all nations should have the same amount of atomic knowledge.

* David Greenglass – an American machinist at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. Greenglass confessed that he gave crude schematics of lab experiments to the Russians during World War II. Some aspects of his testimony against his sister and brother-in-law (the Rosenbergs, see below) are now thought to have been fabricated in an effort to keep his own wife from prosecution. Greenglass confessed to his espionage and was given a long prison term.

* George Koval – The American-born son of a Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

ian emigrant family that returned to the Soviet Union where he was inducted into the Red Army and recruited into the GRU

Gru is a fictional character and the main protagonist of the ''Despicable Me'' film series.

Gru or GRU may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Gru (rapper), Serbian rapper

* Gru, an antagonist in '' The Kine Saga''

Organizations Georgia (c ...

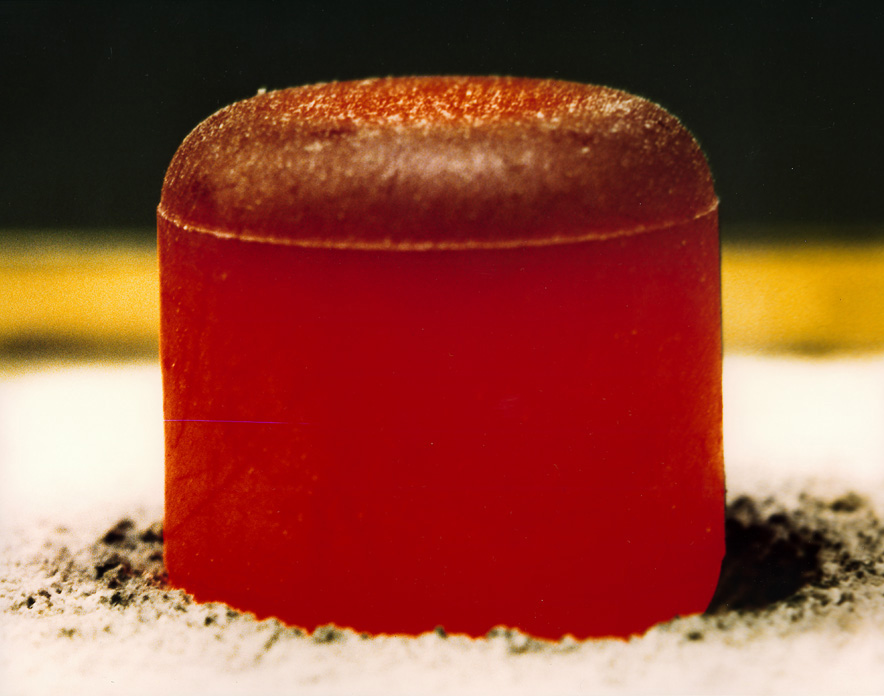

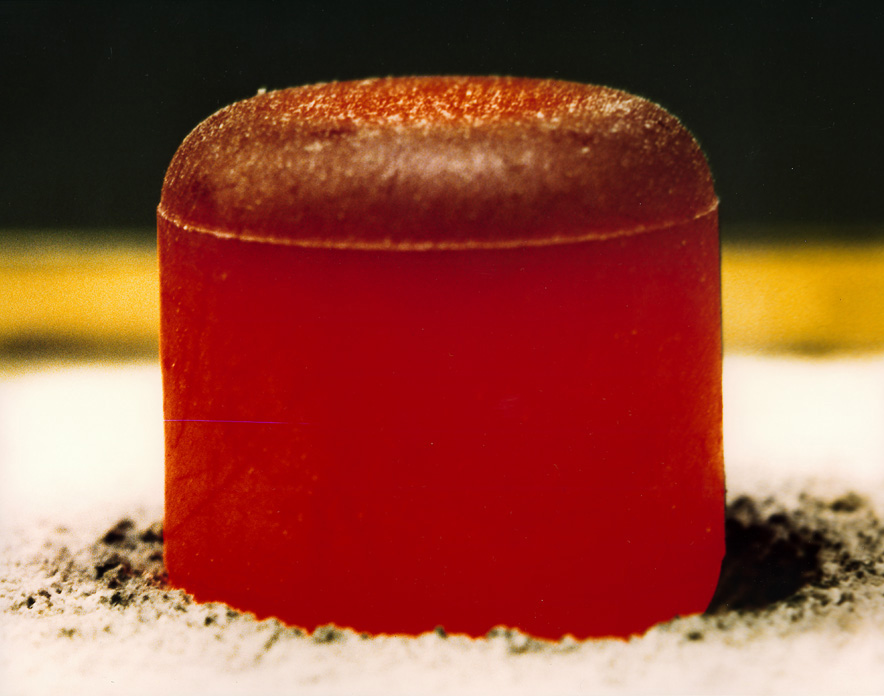

intelligence service. He infiltrated the US Army and became a radiation health officer in the Special Engineering Detachment. Acting under the code name DELMAR he obtained information from Oak Ridge and the Dayton Project about the Urchin (detonator)

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapon design, nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment w ...

used on the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

plutonium bomb. His work was not known to the west until he was posthumously recognized as a hero of the Russian Federation by Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

in 2007.

* Ethel and Julius Rosenberg – Americans who were supposedly involved in coordinating and recruiting an espionage network which included David Greenglass. While most scholars believe that Julius was likely involved in some sort of network, whether or not Ethel was involved or cognizant of the activities remains a matter of dispute. Julius and Ethel refused to confess to any charges, and were convicted and executed at Sing Sing Prison.

* Harry Gold – American, confessed to acting as a courier for Greenglass and Fuchs.

While the spies mentioned previously have become infamous for their actions, more Los Alamos spies have been identified in recent years due in part to the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

releasing previously classified documents. Other spies have become more known after being overlooked by historians.

These include:

* Clarence Hiskey - American-born chemist who worked on the Manhattan Project's metallurgical division and was serving as a Soviet agent. While working on the Manhattan project, he provided several classified documents to the GRU intelligence service. Though Hiskey's contributions to the Soviet Union's development of its own nuclear bomb remain minimal compared to other early spies, he remains one of the first to leak information from Los Alamos. He was never convicted by the U.S. government due to a lack of solid evidence pertaining to his espionage.

* Arthur Adams - a Soviet spy born in Sweden with mixed Russian and Swedish heritage. He served as a courier for several Soviet spies during World War II, and was a GRU contact for Clarence Hiskey. Despite the fact he was not an American citizen, Adams was able to infiltrate the United States and convincingly faked his identity as a Canadian citizen. After successfully exporting many documents over the development of the U.S. atomic bomb, Adams fled back to the Soviet Union after several run-ins with the FBI.

* Oscar Seborer - an American electrical engineer assigned to work on the Manhattan Project within the Special Engineering Detachment. In 2020, five years after his death, historians Harvey Klehr

Harvey Elliott Klehr (born December 25, 1945) is a professor of politics and history at Emory University. Klehr is known for his books on the subject of the American Communist movement, and on Soviet espionage in America (many written jointly with ...

and John Earl Hayes unearthed documents connecting Seborer to the previously known codename Godsend, who was part of a group of Los Alamos scientists spying for the Soviet Union. The quality of the information he leaked is unknown, due to the lack of documentation covering Seborer's time at Los Alamos.

Most Soviet spies were properly convicted, but several evaded indictment due to a lack of evidence. In the case of Arthur Adams, he was watched by the FBI for many years before his escape to the Soviet Union. The FBI had probable cause Adams was engaging in espionage, but critically lacked evidence to proceed against him. The same goes for his associate Clarence Hiskey who was able to live the rest of his life out in the United States even though he was questioned by the FBI several times. Oscar Seborer was the most prevalent case of this, with his involvement not being discovered until decades after his spy work. Documents will continue to be found and more information about these spies and other potential saboteurs will become public knowledge.

Israel

In 1986, a former technician,Mordechai Vanunu

Mordechai Vanunu (; born 14 October 1954), also known as John Crossman, is an Israeli former nuclear technician and peace activist who, citing his opposition to weapons of mass destruction, revealed details of Israel's nuclear weapons program ...

, at the Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

i nuclear facility near Dimona

Dimona (, ) is an Israeli city in the Negev desert, to the south-east of Beersheba and west of the Dead Sea above the Arabah, Arava valley in the Southern District (Israel), Southern District of Israel. In , its population was . The Shimon Pere ...

revealed information about the Israeli nuclear weapon program to the British press, confirming widely held notions that Israel had an advanced and secretive nuclear weapons program and stockpile. Israel has never acknowledged or denied having a weapons program, and Vanunu was abducted and smuggled to Israel, where he was tried ''in camera

''In camera'' (; Latin: "in a chamber"). is a legal term that means ''in private''. The same meaning is sometimes expressed in the English equivalent: ''in chambers''. Generally, ''in-camera'' describes court cases, parts of it, or process wh ...

'' and convicted of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

and espionage.

Whether Vanunu was truly involved in espionage, per se, is debated: Vanunu and his supporters claim that he should be regarded as a whistle-blower

Whistleblowing (also whistle-blowing or whistle blowing) is the activity of a person, often an employee, revealing information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe, unethical or ...

(someone who was exposing a secretive and illegal practice), while his opponents see him as a traitor and his divulgence of information as aiding enemies of the Israeli state. Vanunu did not immediately release his information and photos on leaving Israel, travelling for about a year before doing so. The politics of the case are hotly disputed.

China

In a 1999 report of theUnited States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People's Republic of China, chaired by Rep. Christopher Cox (known as the Cox Report), it was revealed that U.S. security agencies believed that there is ongoing nuclear espionage by the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(PRC) at U.S. nuclear weapons design laboratories, especially Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development Laboratory, laboratories of the United States Department of Energy National Laboratories, United States Department of Energy ...

, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Livermore, California, United States. Originally established in 1952, the laboratory now i ...

, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1943, the laboratory is sponsored by the United Sta ...

, and Sandia National Laboratories

Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), also known as Sandia, is one of three research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Headquartered in Kirtland Air Force B ...

. According to the report, the PRC had "stolen classified information on all of the United States' most advanced thermonuclear warheads" since the 1970s, including the design of advanced miniaturized thermonuclear warheads (which can be used on MIRV weapons), the neutron bomb

A neutron bomb, officially defined as a type of enhanced radiation weapon (ERW), is a low-yield thermonuclear weapon designed to maximize lethal neutron radiation in the immediate vicinity of the blast while minimizing the physical power of the b ...

, and "weapons codes" which allow for computer simulations of nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of Nuclear explosion, their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to si ...

(and allow the PRC to advance their weapon development without testing themselves). The United States was apparently unaware of this until 1995.

The investigations described in the report eventually led to the arrest of Wen Ho Lee, a scientist at Los Alamos, initially accused of giving weapons information to the PRC. The case against Lee eventually fell apart, however, and he was eventually charged only with mishandling of data. Other people and groups arrested or fined were scientist Peter Lee (no relation), who was arrested for allegedly giving submarine radar secrets to China, and Loral Space & Communications and Hughes Electronics

Hughes Electronics Corporation was formed in 1985, when Hughes Aircraft was sold by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to General Motors for $5.2 billion. Surviving parts of Hughes Electronics are today known as DirecTV Group, while the automoti ...

who gave China missile secrets. No other arrests regarding the theft of the nuclear designs have been made. The issue was a considerable scandal at the time.

Pakistan

From 1991—93, during thePrime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto (21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990, and again from 1993 to 1996. She was also the first woman elected to head a democratic governmen ...

's government, an operative directorate of the ISI's Joint Intelligence Miscellaneous (JIM), conducted highly successful operations in Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. This directorate successfully procured nuclear material while many operative were posted as the Defence attaché in the Embassy of Pakistan in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

; and concurrently obtaining other materials from Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and the former Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

.

In January 2004, Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan (1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021) was a Pakistani Nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and metallurgist, metallurgical engineer. He is colloquially known as the "father of Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction, Pakistan's ...

confessed to selling restricted technology to Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, and North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

. According to his testimony and reports from intelligence agencies, he sold designs for gas centrifuge

A gas centrifuge is a device that performs isotope separation of gases. A centrifuge relies on the principles of centrifugal force accelerating molecules so that particles of different masses are physically separated in a gradient along the radiu ...

s (used for uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

), and sold centrifuges themselves to these three countries. Khan had previously been indicated as having taken gas centrifuge

A gas centrifuge is a device that performs isotope separation of gases. A centrifuge relies on the principles of centrifugal force accelerating molecules so that particles of different masses are physically separated in a gradient along the radiu ...

designs from a uranium enrichment company in the Netherlands (URENCO

The Urenco Group is a British-German-Dutch nuclear fuel consortium operating several uranium enrichment plants in Germany, the Netherlands, United States, and United Kingdom. It supplies nuclear power stations in about 15 countries, and stat ...

) which he used to jump-start Pakistan's own nuclear weapons program. On February 5, 2004, the president of Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf

Pervez Musharraf (11 August 1943 – 5 February 2023) was a Pakistani general and politician who served as the tenth president of Pakistan from 2001 to 2008.

Prior to his career in politics, he was a four-star general and appointed as ...

, announced that he had pardoned Khan. Pakistan's government claims they had no part in the espionage, but refuses to turn Khan over for questioning by the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology, nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was ...

.

Iran

When looking at future nuclear espionage all fingers are pointed atIran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. Their aspirations for obtaining nuclear weapons dates back to the 1970s. Those aspirations only grew stronger in the 1980s when the Iran-Iraq war broke out. This led nuclear research to become a major priority not only at the governmental level, but also at the private level. Iran has stated that their reason for nuclear research is for solely nonmilitary purposes such as for agricultural, medical, and industrial advancements.

The world powers do not like the addition of more countries with the opportunity to create nuclear weapons. Due to this the world powers made deals with Iran which led to the halt of nuclear research in the 2010s. This did not last long before IAEA

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

started to get test readings that showed Iran had enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

over eighty percent. This is higher enrichment than the little boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project during World War II. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ...

bomb that was used at Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

which was right at eighty percent. That let the world know that Iran had the capability to enrich to a level great enough to produce a working nuclear weapon. The other thing they would need is a working bomb designed which is easier to steal than to discover. This has been shown by the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, and Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

.

The ways of committing espionage have multiplied with the increase dependence on technology. This venerability is where a nation like Iran can benefit. They have one of the world's best cyber arsenals, and it only continues to grow. This allows them to perform cyberattacks much like

The ways of committing espionage have multiplied with the increase dependence on technology. This venerability is where a nation like Iran can benefit. They have one of the world's best cyber arsenals, and it only continues to grow. This allows them to perform cyberattacks much like North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

has done to either gain access to nuclear weapon plans or get them as ransom. The United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

would both be likely targets of a cyber espionage attack by Iran due to their previous attack on Iran. The attack by the United States and Israel was a malware called Stuxnet

Stuxnet is a Malware, malicious computer worm first uncovered on June 17, 2010, and thought to have been in development since at least 2005. Stuxnet targets supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems and is believed to be responsibl ...

that was sold to Iran which eventually caused severe damage to their nuclear program There are other reasons it is believed that Iran may use cyberattacks to acquire the missing link to their nuclear weapons development. That is because they have used cyberattacks before even on the United States with regard to the attack on JPMorgan

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (stylized as JPMorganChase) is an American multinational finance corporation headquartered in New York City and incorporated in Delaware. It is the largest bank in the United States, and the world's largest bank by mar ...

. This attack was linked to seven Iranians by the United States Justice Department

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the U.S. government that oversees the domestic enforcement of federal laws and the administration of justice. It is equi ...

. This new era of technology gives places like Iran the opportunity to retaliate. The most dangerous way they can retaliate is to commit espionage to acquire working nuclear weapon designs. This will most likely lead to an increase in nuclear weapons research in surrounding countries. That is dangerous because of the religious disagreements in the area between the Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

(Egypt) and Shia

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood ...

(Iran) Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

.

This new cyber aspect of espionage has led to many efforts by nuclear weapons welding countries to scour their systems to try to find weak spots where there are venerable. Some countries have even started pouring money into cyber defense programs like United Kingdom. They have annually put two billion dollars toward a cyber defense

Proactive cyber defense means acting in anticipation to oppose an attack through cyber and cognitive domains. Proactive cyber defense can be understood as options between offensive and defensive measures. It includes interdicting, disrupting or d ...

system in an attempt to keep their assets protected. Espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

has become easier with a whole new route to gain access to private information. It has also become a harder thing to prevent.

India

India's path to become a nuclear power began with successful nuclear detonation during the operation known asSmiling Buddha

Smiling Buddha (Ministry of External Affairs (India), MEA designation: Pokhran-I) was the code name of India's first successful Nuclear weapons testing, nuclear weapon test on 18 May 1974. The nuclear fission bomb was detonated in the Pokhran#P ...

in 1974. The official name for the project was Pokhran-I. It wasn't until May 13, 1998 that Pokhran-II

Pokhran-II (''Operation Shakti'') was a series of five nuclear weapon tests conducted by India in May 1998. The bombs were detonated at the Indian Army's Pokhran Test Range in Rajasthan. It was the second instance of nuclear testing conducted ...

, the next major development of India's nuclear weapons program, was detonated. It consisted of one fusion bomb and four fission bombs. This led then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Atal Bihari Vajpayee (25 December 1924 – 16 August 2018) was an Indian poet, writer and statesman who served as the prime minister of India, first for a term of 13 days in 1996, then for a period of 13 months from 1998 ...

to officially declare India as a nuclear power. However, India was involved in the nuclear dealings of the world much sooner than this.

India was involved with assisting espionage between the

India was involved with assisting espionage between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

in October 1965. The Central Intelligence Agency, CIA enlisted 14 American climbers to scale Nanda Devi and working in cooperation with the Intelligence Bureau (India), Indian Intelligence Bureau, successfully planned the Nanda Devi Plutonium Mission. The objective of the mission was for the 14 climbers to work in unison to place a Radioisotope thermoelectric generator, Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG), powering a detector on the peak of Nanda Devi, thus allowing the U.S. to spy on China. More specifically, the Xinjiang Province. This was due to the lack of intelligence that the U.S. had on Chinese nuclear capacities during the Vietnam War. Ultimately, the mission failed due to one of the generators being lost during a snowstorm. However, this failed mission has had lasting impact on the region. Snow from the mountain carries into the Ganges, a crucial river for the survival and daily lives of millions of people that live in this region. It is thought that the generator was carried down the mountain by an avalanche. The river also has significant religious and spiritual importance to Hindus, who worship the river as Ganga (goddess), Ganga. The CIA, knowing about the radioactive material being lost, sent climbers back to the area to search for the generator in 1966. This attempt was unsuccessful. In 1967 a new generator was sent with the climbers and was placed atop the peak of Nanda Kot. This mission was a success, and the U.S. was able to spy on the Chinese region.

On October 30, 2019 the Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) made an official announcement that the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant in Tamil Nadu was the victim of a cyberattack. The attack happened earlier that year in September, but the NPCIL was hesitant to go public with the news, stating that a cyberattack on the facility was not possible. Only a single computer was attacked by the perpetrator. It's not clear what information was stolen at the time, but top officials related to the incident are not convinced that future attacks will be prevented. Speculation about the perpetrator has been discussed, specifically about what type of malware was used to hack into the system. The malware, known as "Dtrack", has similarities to attacks from North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

. This makes them a possible target, especially with their past of other malware attacks.

See also

* Atomic spies * Soviet espionage in the United StatesReferences

{{reflist ;Manhattan Project *Richard Rhodes, Rhodes, Richard. ''Dark Sun: The Making of the Atomic Bomb''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ;Israel *Cohen, Avner. ''Israel and the Bomb''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ;People's Republic of China *Cox, Christopher, chairman (1999). ''Report of the United States House of Representatives Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People's Republic of China''., esp. Ch. 2, "PRC Theft of U.S. Thermonuclear Warhead Design Information". Available online at https://web.archive.org/web/20050804234332/http://www.house.gov/coxreport/. *Stober, Dan, and Ian Hoffman. ''A convenient spy: Wen Ho Lee and the politics of nuclear espionage''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ;Pakistan *Powell, Bill, and Tim McGirk. "The Man Who Sold the Bomb; How Pakistan's A.Q. Khan outwitted Western intelligence to build a global nuclear-smuggling ring that made the world a more dangerous place", ''Time Magazine'' (14 February 2005): 2Iran

India

* Thomas O'Toole. "CIA Put Nuclear Spy Devices in Himalayas", ''Washington Post'' (13 April 1978) * William Borders. "Desai Says U.S.-Indian Team Lost Atomic Spy Gear", ''The New York Times'' (18 April 1978) Types of espionage Nuclear weapons Nuclear secrecy