Mountain Meadows massacre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mountain Meadows Massacre (September 7–11, 1857) was a series of attacks during the

While most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail, rumors spread about their supposed misdeeds. U.S. Army Brevet Major

While most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail, rumors spread about their supposed misdeeds. U.S. Army Brevet Major

– In Carleton's investigation, at Mountain Meadows he found women's hair tangled in sage brush and the bones of children still in their mothers' arms. Carleton later said it was "a sight which can never be forgotten." After gathering up the skulls and bones of those who had died, Carleton's troops buried them and erected a cairn and cross. Carleton interviewed a few local Mormon settlers and Paiute Native American chiefs and concluded that there was Mormon involvement in the massacre. He issued a report in May 1859, addressed to the U.S. Assistant Adjutant-General, setting forth his findings. Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, also conducted an investigation that included visiting the region in the summer of 1859. Forney retrieved many of the surviving children of massacre victims who had been housed with Mormon families and gathered them up for transportation to their relatives in Arkansas. He concluded that the Paiutes did not act alone and the massacre would not have occurred without the white settlers, while Carleton's report to the

Further investigations were cut short by the

Further investigations were cut short by the

Initial published reports of the incident date back at least to October 1857 in the ''

Initial published reports of the incident date back at least to October 1857 in the ''

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events relating to the Utah War, an 1857 deployment toward the Utah Territory of the United States Army, whose arrival was peaceful. In the summer of 1857, however, the Mormons expected an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders and their followers prepared for a siege that could have ended up similar to the seven-year

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events relating to the Utah War, an 1857 deployment toward the Utah Territory of the United States Army, whose arrival was peaceful. In the summer of 1857, however, the Mormons expected an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders and their followers prepared for a siege that could have ended up similar to the seven-year

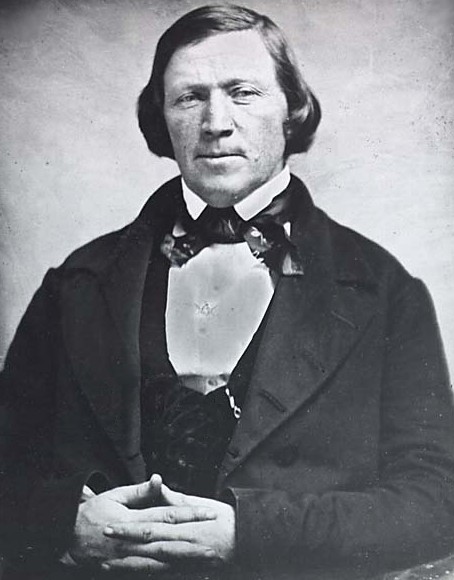

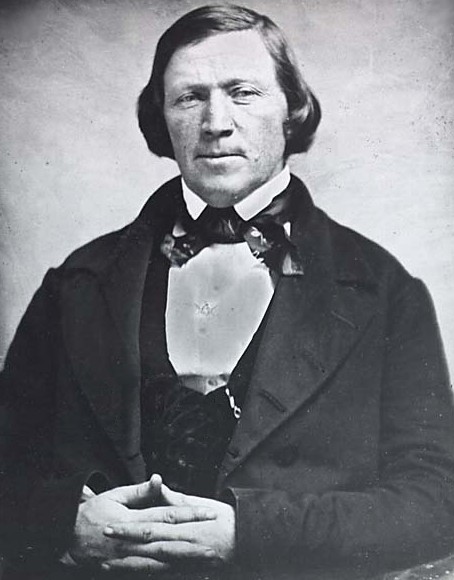

There is a consensus among historians that Brigham Young played a role in provoking the massacre, at least unwittingly, and in concealing its evidence after the fact. However, they debate whether Young knew about the planned massacre ahead of time and whether he initially condoned it before later taking a strong public stand against it. Young's use of inflammatory and violent language in response to the Federal expedition added to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. Following the massacre, Young stated in public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Baker–Fancher party. It is unclear whether Young held this view because he believed that this specific group posed an actual threat to colonists or because he believed that the group was directly responsible for past crimes against Mormons. However, in Young's only known correspondence prior to the massacre, he told the Church leaders in Cedar City:

According to historian MacKinnon, "After the tahwar, U.S. President James Buchanan implied that face-to-face communications with Brigham Young might have averted the conflict, and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah could have prevented the Mountain Meadows massacre." MacKinnon suggests that hostilities could have been avoided if Young had traveled east to Washington D.C. to resolve governmental problems instead of taking a five-week trip north on the eve of the Utah War for church related reasons.

A modern forensic assessment of a key affidavit, purportedly given by William Edwards in 1924, has complicated the debate on complicity of senior Mormon leadership in the Mountain Meadows massacre. Analysis indicates that Edwards's signature may have been traced and that the typeset belonged to a typewriter manufactured in the 1950s. The

There is a consensus among historians that Brigham Young played a role in provoking the massacre, at least unwittingly, and in concealing its evidence after the fact. However, they debate whether Young knew about the planned massacre ahead of time and whether he initially condoned it before later taking a strong public stand against it. Young's use of inflammatory and violent language in response to the Federal expedition added to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. Following the massacre, Young stated in public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Baker–Fancher party. It is unclear whether Young held this view because he believed that this specific group posed an actual threat to colonists or because he believed that the group was directly responsible for past crimes against Mormons. However, in Young's only known correspondence prior to the massacre, he told the Church leaders in Cedar City:

According to historian MacKinnon, "After the tahwar, U.S. President James Buchanan implied that face-to-face communications with Brigham Young might have averted the conflict, and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah could have prevented the Mountain Meadows massacre." MacKinnon suggests that hostilities could have been avoided if Young had traveled east to Washington D.C. to resolve governmental problems instead of taking a five-week trip north on the eve of the Utah War for church related reasons.

A modern forensic assessment of a key affidavit, purportedly given by William Edwards in 1924, has complicated the debate on complicity of senior Mormon leadership in the Mountain Meadows massacre. Analysis indicates that Edwards's signature may have been traced and that the typeset belonged to a typewriter manufactured in the 1950s. The

Starting in 1988, the Mountain Meadows Association, composed of descendants of both the Baker–Fancher party victims and the Mormon participants, designed a new monument in the meadows; this monument was completed in 1990 and is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation. In 1999 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints replaced the U.S. Army's cairn and the 1932 memorial wall with a second monument, which it now maintains. In August 1999, when the LDS Church's construction of the 1999 monument had started, the remains of at least 28 massacre victims were dug up by a backhoe. The forensic evidence showed that the remains of the males had been shot by firearms at close range and that the remains of the women and children showed evidence of blunt force trauma.

Starting in 1988, the Mountain Meadows Association, composed of descendants of both the Baker–Fancher party victims and the Mormon participants, designed a new monument in the meadows; this monument was completed in 1990 and is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation. In 1999 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints replaced the U.S. Army's cairn and the 1932 memorial wall with a second monument, which it now maintains. In August 1999, when the LDS Church's construction of the 1999 monument had started, the remains of at least 28 massacre victims were dug up by a backhoe. The forensic evidence showed that the remains of the males had been shot by firearms at close range and that the remains of the women and children showed evidence of blunt force trauma.

In 1955, to memorialize the victims of the massacre, a monument was installed in the town square of

In 1955, to memorialize the victims of the massacre, a monument was installed in the town square of

Mountain Meadows.

' – an article originally published in the Cincinnati Gazette (July 21, 1875), then republished in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat(July 26, 1875). An affidavit of James Lynch's testimony taken in July 1859 about the human remains Lynch saw at Mount Meadows in March and April 1858, about the living conditions of the child survivors of the Massacre during that time, and about the children's statements regarding the perpetrators of the Massacre. Lynch accompanied Dr. Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, on an expedition to the area. The affidavit was given in front of Chief Justice of the Utah Territory Supreme Court Delana R. Eckels on July 27, 1859, and sent by US Army officer S.H. Montgomery to Commissioner of Indian Affairs A.B. Greenwood in August 1859.

scanned versions

. * * * . * * .

published by Mountain Meadows Association * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * .

Mountain Meadows Association

Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation

* ttp://signaturebookslibrary.org/?p=431''The Mountain Meadows Massacre: A Bibliographic Perspective'' by Newell Bringhurst* United States Office of Indian Affairs Papers Relating to Charges Against Jacob Forney. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{Authority control 1857 murders in the United States 1857 in Utah Territory Massacres in 1857 American murder victims Battles involving Native Americans Crimes in Utah Criticism of Mormonism Deaths by firearm in Utah Massacres in the United States Mormonism and Native Americans - Murdered American children Nauvoo Legion Utah War

Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train. The massacre occurred in the southern Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

at Mountain Meadows, and was perpetrated by the Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into severa ...

settlers belonging to the Utah Territorial Militia (officially called the Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Saint ...

) who recruited and were aided by some Southern Paiute Native Americans. The wagon train, made up mostly of families from Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

, was bound for California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, traveling on the Old Spanish Trail that passed through the Territory.

After arriving in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

, the Baker–Fancher party made their way south along the Mormon Road

Mormon Road, also known to the 49ers as the Southern Route, of the California Trail in the Western United States, was a seasonal wagon road pioneered by a Mormon party from Salt Lake City, Utah led by Jefferson Hunt, that followed the route of ...

, eventually stopping to rest at Mountain Meadows. As the party was traveling west there were rumors about the party's behavior towards Mormons, and war hysteria towards outsiders was rampant as a result of a military expedition dispatched by President Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

and Territorial Governor Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his death in 1877. During his time as ch ...

's declaration of martial law in response to the invasion. While the emigrants were camped at the meadow, local militia leaders, including Isaac C. Haight

Isaac Chauncey Haight (May 27, 1813 – September 8, 1886), an early convert to the Latter Day Saint Movement, was a pioneer of the American West best remembered as a ringleader in the Mountain Meadows massacre.

He was raised on a farm in Ne ...

and John D. Lee, made plans to attack the wagon train. The leaders of the militia, wanting to give the impression of tribal hostilities, persuaded Southern Paiutes to join with a larger party of militiamen disguised as Native Americans in an attack. During the militia's first assault on the wagon train, the emigrants fought back, and a five-day siege ensued. Eventually, fear spread among the militia's leaders that some emigrants had caught sight of the white men, likely discerning the actual identity of a majority of the attackers. As a result, militia commander William H. Dame ordered his forces to kill the emigrants. By this time, the emigrants were running low on water and provisions, and allowed some members of the militia—who approached under a white flag—to enter their camp. The militia members assured the emigrants they were protected, and after handing over their weapons, the emigrants were escorted away from their defensive position. After walking a distance from the camp, the militiamen, with the help of auxiliary forces hiding nearby, attacked the emigrants. The perpetrators killed all the adults and older children in the group, in the end sparing only seventeen young children under the age of seven.

Following the massacre, the perpetrators buried some of the remains but ultimately left most of the bodies exposed to wild animals and the climate. Local families took in the surviving children, with many of the victims' possessions and remaining livestock being auctioned off. Investigations, which were interrupted by the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, resulted in nine indictments in 1874. Of the men who were indicted, only John D. Lee was tried in a court of law. After two trials in the Utah Territory, Lee was convicted by a jury, sentenced to death, and executed by Utah firing squad on March 23, 1877.

Historians attribute the massacre to a combination of factors, including war hysteria about a possible invasion of Mormon territory and Mormon teachings against outsiders, which were part of the Mormon Reformation

The Mormon Reformation was a period of renewed emphasis on spirituality within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a centrally-directed movement, which called for a spiritual reawakening among church members. It took p ...

period. Scholars debate whether senior Mormon leadership, including Brigham Young, directly instigated the massacre or if responsibility for it lay only with the local leaders in southern Utah.

History

Baker–Fancher party

In early 1857, the Baker–Fancher party was formed from several groups mainly fromMarion Marion may refer to:

People

*Marion (given name)

*Marion (surname)

*Marion Silva Fernandes, Brazilian footballer known simply as "Marion"

*Marion (singer), Filipino singer-songwriter and pianist Marion Aunor (born 1992)

Places Antarctica

* Mario ...

, Crawford, Carroll, and Johnson

Johnson is a surname of Anglo-Norman origin meaning "Son of John". It is the second most common in the United States and 154th most common in the world. As a common family name in Scotland, Johnson is occasionally a variation of ''Johnston'', a ...

counties in northwestern Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

. They assembled into a wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957–1962), and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings ...

at Beller's Stand, south of Harrison

Harrison may refer to:

People

* Harrison (name)

* Harrison family of Virginia, United States

Places

In Australia:

* Harrison, Australian Capital Territory, suburb in the Canberra district of Gungahlin

In Canada:

* Inukjuak, Quebec, or " ...

, to emigrate to southern California. The group was initially referred to as both the Baker train and the Perkins train, but later referred to as the Baker–Fancher train (or party). It was named after "Colonel" Alexander Fancher who, having already made the journey to California twice before, had become its main leader. By contemporary standards the Baker–Fancher party was prosperous, carefully organized, and well-equipped for the journey. They were joined along the way by families and individuals from other states, including Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

. The group was relatively wealthy, and planned to restock its supplies in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

, as did most wagon trains at the time.

Interactions with Mormon settlers

At the time of the Fanchers' arrival, theUtah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

was organized as a theocratic democracy under the leadership of Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his death in 1877. During his time as ch ...

, who had established colonies along the California Trail and the Old Spanish Trail. President James Buchanan had recently issued an order to send troops to Utah which led to rumors being spread in the territory about its motives. Young issued various orders that urged the local population to prepare for the arrival of the troops. Eventually Young issued a declaration of martial law.

The Baker–Fancher party was refused stocks in Salt Lake City and chose to leave there and take the Old Spanish Trail, which passed through southern Utah. In August 1857, the Mormon apostle George A. Smith traveled throughout the southern part of the territory instructing the settlers to stockpile grain. While on his return trip to Salt Lake City, Smith camped near the Baker–Fancher party on August 25 at Corn Creek. They had traveled the south from Salt Lake City, and Jacob Hamblin

Jacob Hamblin (April 2, 1819 – August 31, 1886) was a Western pioneer, a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a diplomat to various Native American tribes of the Southwest and Great Basin. He ...

suggested that the wagon train continue on the trail and rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows, which had good pasture and was adjacent to his homestead.

While most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail, rumors spread about their supposed misdeeds. U.S. Army Brevet Major

While most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail, rumors spread about their supposed misdeeds. U.S. Army Brevet Major James Henry Carleton

James Henry Carleton (December 27, 1814 – January 7, 1873) was an officer in the US Army and a Union general during the American Civil War. Carleton is best known as an Indian fighter in the Southwestern United States.

Biography

Carleton wa ...

led the first federal investigation of the murders, published in 1859. He recorded Hamblin's account that the train was alleged to have poisoned a spring near Corn Creek; this resulted in the deaths of 18 head of cattle and two or three people who ate the contaminated meat. Carleton interviewed the father of a child who allegedly died from this poisoned spring, and accepted the sincerity of the grieving father. But, he also included a statement from an investigator who did not believe the Fancher party was capable of poisoning the spring, given its size. Carleton invited readers to consider a potential explanation for the rumors of misdeeds, noting the general atmosphere of distrust among Mormons for strangers at the time, and that some locals appeared jealous of the Fancher party's wealth.

Conspiracy and siege

The Baker–Fancher party left Corn Creek and continued the to Mountain Meadows, passing Parowan andCedar City

Cedar City is the largest city in Iron County, Utah, United States. It is located south of Salt Lake City, and north of Las Vegas on Interstate 15. It is the home of Southern Utah University, the Utah Shakespeare Festival, the Utah Summer Gam ...

, southern Utah communities led respectively by Stake President

A stake is an administrative unit composed of multiple congregations in certain denominations of the Latter Day Saint movement. The name "stake" derives from the Book of Isaiah: "enlarge the place of thy tent; stretch forth the curtains of thine ha ...

s William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight

Isaac Chauncey Haight (May 27, 1813 – September 8, 1886), an early convert to the Latter Day Saint Movement, was a pioneer of the American West best remembered as a ringleader in the Mountain Meadows massacre.

He was raised on a farm in Ne ...

. Haight and Dame were, in addition, the senior regional military leaders of the Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Saint ...

. As the Baker–Fancher party approached, several meetings were held in Cedar City and nearby Parowan by the local Latter Day Saint

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by J ...

(LDS) leaders pondering how to implement Young's declaration of martial law. On the afternoon of Sunday, September 6, Haight held his weekly Stake High Council meeting after church services and brought up the issue of what to do with the emigrants. The plan for a Native American massacre was discussed, but not all the Council members agreed it was the right approach. The Council resolved to take no action until Haight sent a rider, James Haslam, out the next day to carry an express to Salt Lake City (a six-day round trip on horseback) for Brigham Young's advice, as Utah did not yet have a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

system. Following the council, Isaac C. Haight decided to send a messenger south to John D. Lee. What Haight told Lee remains a mystery, but considering the timing it may have had something to do with Council's decision to wait for advice from Brigham Young.

The dispirited Baker–Fancher party found water and fresh grazing for its livestock after reaching grassy, mountain-ringed Mountain Meadows, a widely known stopover on the old Spanish Trail, in early September. They anticipated several days of rest and recuperation there before the next would take them out of Utah. On September 7, the party was attacked by Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Saint ...

militiamen dressed as Native Americans and some Native American Paiute

Paiute (; also Piute) refers to three non-contiguous groups of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. Although their languages are related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, these three groups do not form a single set. The term "Paiu ...

s. The Baker–Fancher party defended itself by encircling and lowering their wagons, wheels chained together, along with digging shallow trenches and throwing dirt both below and into the wagons, which made a strong barrier. Seven emigrants were killed during the opening attack and buried somewhere within the wagon encirclement. Sixteen more were wounded.Brigham Young: American Moses, Leonard J. Arrington, University of Illinois Press, (1986), p. 257 The attack continued for five days, during which the besieged families had little or no access to freshwater or game food and their ammunition was depleted. Meanwhile, organization among the local Mormon leadership reportedly broke down. Eventually, fear spread among the militia's leaders that some emigrants had caught sight of white men, and had probably discerned the identity of their attackers. This resulted in an order to kill all the emigrants, with the exception of small children.

Killings and aftermath of the massacre

On Friday, September 11, 1857, two militiamen approached the Baker–Fancher party wagons with a white flag and were soon followed byIndian Agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

and militia officer John D. Lee. Lee told the battle-weary emigrants that he had negotiated a truce with the Paiutes. Under Mormon protection, the wagon-train members would be escorted safely back to Cedar City, away, in exchange for turning all of their livestock and supplies over to the Native Americans. Accepting this offer, the emigrants were led out of their fortification, with the adult men being separated from the women and children. The men were paired with a militia escort and when the signal was given, the militiamen turned and shot the male members of the Baker–Fancher party standing by their side. The women and children were then ambushed and killed by more militia that were hiding in nearby bushes and ravines. Members of the militia were sworn to secrecy. A plan was set to blame the massacre on the Native Americans.

The militia did not kill small children who were deemed too young to relate what had happened. Nancy Huff, one of the seventeen survivors and just over four years old at the time of the massacre, recalled in an 1875 statement that an eighteenth survivor was killed directly in front of the other children. "At the close of the massacre there was eighteen children still alive, one girl, some ten or twelve years old, they said was too big and could tell, so they killed her, leaving seventeen." The survivors were taken in by local Mormon families. Seventeen of the children were later reclaimed by the U.S. Army and returned to relatives in Arkansas. The treatment of these children while they were held by the Mormons is uncertain, but Captain James Lynch's statement in May 1859 said the surviving children were "in a most wretched condition, half starved, half naked, filthy, infested with vermin, and their eyes diseased from the cruel neglect to which had been exposed." Lynch's July 1859 affidavit added that they when they first saw the children they had "little or no clothing" and were "covered with filth and dirt".

Leonard J. Arrington, founder of the Mormon History Association, reports that Brigham Young received the rider, James Haslam, at his office on the same day. When he learned what was contemplated by the militia leaders in Parowan and Cedar City, he sent back a letter stating the Baker–Fancher party was not to be meddled with, and should be allowed to go in peace (although he acknowledged the Native Americans would likely "do as they pleased"). Young's letter arrived two days too late, on September 13, 1857.

The livestock and personal property of the Baker–Fancher party, including women's jewelry, clothing and bedstuffs were distributed or auctioned off to Mormons. Some of the surviving children saw clothing and jewelry that had belonged to their dead mothers and sisters subsequently being worn by Mormon women and the journalist J.H. Beadle said that jewelry taken from Mountain Meadows was seen in Salt Lake City.

Investigations and prosecutions

An early investigation was conducted by Brigham Young, who interviewed John D. Lee on September 29, 1857. In 1858, Young sent a report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs stating that the massacre was the work of Native Americans. TheUtah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

delayed any investigation by the U.S. federal government until 1859, when Jacob Forney and U.S. Army Brevet Major James Henry Carleton

James Henry Carleton (December 27, 1814 – January 7, 1873) was an officer in the US Army and a Union general during the American Civil War. Carleton is best known as an Indian fighter in the Southwestern United States.

Biography

Carleton wa ...

conducted investigations.– In Carleton's investigation, at Mountain Meadows he found women's hair tangled in sage brush and the bones of children still in their mothers' arms. Carleton later said it was "a sight which can never be forgotten." After gathering up the skulls and bones of those who had died, Carleton's troops buried them and erected a cairn and cross. Carleton interviewed a few local Mormon settlers and Paiute Native American chiefs and concluded that there was Mormon involvement in the massacre. He issued a report in May 1859, addressed to the U.S. Assistant Adjutant-General, setting forth his findings. Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, also conducted an investigation that included visiting the region in the summer of 1859. Forney retrieved many of the surviving children of massacre victims who had been housed with Mormon families and gathered them up for transportation to their relatives in Arkansas. He concluded that the Paiutes did not act alone and the massacre would not have occurred without the white settlers, while Carleton's report to the

U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

called the mass killings a "heinous crime", blaming both local and senior church leaders for the massacre.

In March 1859, Judge John Cradlebaugh, a federal judge brought into the territory after the Utah War, convened a grand jury in Provo concerning the massacre, but the jury declined any indictments. Nevertheless, Cradlebaugh conducted a tour of the Mountain Meadows area with a military escort. He attempted to arrest John D. Lee, Isaac Haight, and John Higbee, who fled before they could be found. Cradlebaugh publicly charged Brigham Young as an instigator to the massacre and therefore an "accessory before the fact". Possibly as a protective measure against the mistrusted federal court system, Mormon territorial probate court judge Elias Smith arrested Young under a territorial warrant, perhaps hoping to divert any trial of Young into a friendly Mormon territorial court. Apparently because no federal charges ensued, Young was released.

Further investigations were cut short by the

Further investigations were cut short by the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

in 1861, but proceeded in 1871 when prosecutors obtained the affidavit of militia member Philip Klingensmith. Klingensmith had been a bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is c ...

and blacksmith from Cedar City; by the 1870s, however, he had left the church and moved to Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

.

Lee was arrested on November 7, 1874. Dame, Philip Klingensmith, Ellott Willden, and George Adair, Jr. were indicted and arrested while warrants to pursue the arrests of four others who had gone into hiding (Haight, Higbee, William C. Stewart, and Samuel Jukes) were being obtained. Klingensmith escaped prosecution by agreeing to testify. Brigham Young removed some participants including Haight and Lee from the LDS Church in 1870. The U.S. posted bounties of $5000 ($ in present-day funds) each for the capture of Haight, Higbee, Stewart, and Klingensmith.

Lee's first trial began on July 23, 1875, in Beaver, before a jury of eight Mormons and four non-Mormons. One of Lee's defense attorneys was Enos D. Hoge, a former territorial supreme court justice. The trial led to a hung jury

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again.

T ...

on August 5, 1875. Lee's second trial began September 13, 1876, before an all-Mormon jury. The prosecution called Daniel Wells, Laban Morrill, Joel White, Samuel Knight, Samuel McMurdy, Nephi Johnson, and Jacob Hamblin. Lee also stipulated, against advice of counsel, that the prosecution be allowed to re-use the depositions of Young and Smith from the previous trial. Lee called no witnesses in his defense, and was convicted.

Lee was entitled under Utah Territorial statute to choose the method of his execution from three possible options: hanging, firing squad, or decapitation. At sentencing, Lee chose to be executed by firing squad. In his final words before his sentence was carried out at Mountain Meadows on March 23, 1877, Lee said that he was a scapegoat for others involved. Brigham Young stated that Lee's fate was just, but it was not a sufficient blood atonement

Blood atonement is a disputed doctrine in the history of Mormonism, under which the atonement of Jesus does not redeem an eternal sin. To atone for an eternal sin, the sinner should be killed in a way that allows his blood to be shed upon the gr ...

, given the enormity of the crime.

Criticism and analysis of the massacre

Media coverage about the event

Initial published reports of the incident date back at least to October 1857 in the ''

Initial published reports of the incident date back at least to October 1857 in the ''Los Angeles Star

''Los Angeles Star'' (''La Estrella de Los Angeles'') was the first newspaper in Los Angeles, California, U.S. The publication ran from 1851 to 1879.

History Early history and background

The first proposition to establish a newspaper in Los ...

''. A notable report on the incident was made in 1859 by Carleton, who had been tasked by the U.S. Army to investigate the incident and bury the still exposed corpses at Mountain Meadows. The first period of intense nationwide publicity about the massacre began around 1872 after investigators obtained Klingensmith's confession. In 1868 C. V. Waite published "An Authentic History Of Brigham Young" which described the events. In 1872, Mark Twain commented on the massacre through the lens of contemporary American public opinion in an appendix to his semi-autobiographical travel book '' Roughing It''. In 1873, the massacre was given a full chapter in T. B. H. Stenhouse

Thomas Brown Holmes Stenhouse (21 February 1825 – 7 March 1882) was an early Mormon pioneer and Mormon missionary, missionary who later became a Godbeite and with his wife, Fanny Stenhouse, became a vocal opponent of the Church of Jesus Christ ...

's Mormon history '' The Rocky Mountain Saints''. The massacre itself also received international attention, with various international and national newspapers also covering John D. Lee's 1874 and 1877 trials as well as his execution in 1877.

The massacre has been treated extensively by several historical works, beginning with Lee's own ''Confession'' in 1877, expressing his opinion that George A. Smith was sent to southern Utah by Brigham Young to direct the massacre.

In 1910, the massacre was the subject of a short book by Josiah F. Gibbs, who also attributed responsibility for the massacre to Young and Smith. The first detailed and comprehensive work using modern historical methods was '' The Mountain Meadows Massacre'' in 1950 by Juanita Brooks

Juanita Pulsipher Brooks (January 15, 1898 – August 26, 1989) was an American historian and author, specializing in the American West and Mormon history, including books related to the Mountain Meadows Massacre, to which her grandfather Dudley ...

, a Mormon scholar who lived near the area in southern Utah. Brooks found no evidence of direct involvement by Brigham Young, but charged him with obstructing the investigation and provoking the attack through his rhetoric.

Initially, the LDS Church denied any involvement by Mormons, and was relatively silent on the issue. In 1872, it excommunicated some of the participants for their role in the massacre. Since then, the LDS Church has condemned the massacre and acknowledged involvement by local Mormon leaders. In September 2007, the LDS Church published an article marking 150 years since the tragedy occurred, containing its first official apology about the massacre.

Varying perspectives of the massacre

As described by Richard E. Turley Jr., Ronald W. Walker, andGlen M. Leonard Glen Milton Leonard (born 1938) is an American historian specializing in Mormon history.

Background

Leonard is a native of Farmington, Utah. He received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Utah. For a time he was managing editor of ''U ...

, historians from different backgrounds have taken different approaches to describe the massacre and those involved:

*Portrayal of the perpetrators (white Mormon settlers) as fundamentally good and the Baker-Fancher party as evil people who committed outrageous acts of anti-Mormon instigation prior to the massacre;

*The polar opposite view, that the perpetrators were evil and that the emigrants were innocent;

*Both the perpetrators and victims of the massacre were complicated, and that many different coinciding circumstances led the Mormon settlers to commit an atrocity against travelers who, regardless of the authenticity of any unfounded claims of anti-Mormon behavior, did not deserve the punishment of death.

Prior to 1985, many textbooks available in Utah Public Schools blamed the Paiute people as primarily responsible for the massacre, or placed equal blame on the Paiute and Mormon settlers (if they mentioned the massacre at all).

Theories explaining the massacre

Historians have ascribed the massacre to a number of factors, including strident Mormon teachings in the years prior to the massacre, war hysteria, and alleged involvement of Brigham Young.Strident Mormon teachings

For the decade prior to the Baker–Fancher party's arrival there, Utah Territory existed as a theodemocracy led by Brigham Young. During the mid-1850s, Young instituted aMormon Reformation

The Mormon Reformation was a period of renewed emphasis on spirituality within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a centrally-directed movement, which called for a spiritual reawakening among church members. It took p ...

, intending to "lay the axe at the root of the tree of sin and iniquity". In January 1856, Young said "the government of God, as administered here" may to some seem "despotic" because "...judgment is dealt out against the transgression of the law of God."

In addition, during the preceeding decades, the religion had undergone a period of intense persecution in the American Midwest. In particular, they were officially expelled from, and an Extermination Order was issued by Governor Boggs, of the state of Missouri during the 1838 Mormon War

The 1838 Mormon War, also known as the Missouri Mormon War, was a conflict between Mormons and non-Mormons in Missouri from August to November 1838, the first of the three " Mormon Wars".

Members of the Latter Day Saint movement, founded by J ...

, during which prominent Mormon apostle David W. Patten was killed in battle. After Mormons moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, the religion's founder Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, ...

and his brother Hyrum Smith

Hyrum Smith (February 9, 1800 – June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, the original church of the Latter Day Saint movement. He was the older brother of the movement's founder, J ...

were killed in 1844. Following these events, faithful Mormons migrated west hoping to escape persecution. However, in May 1857, just months before the Mountain Meadows massacre, apostle Parley P. Pratt

Parley Parker Pratt Sr. (April 12, 1807 – May 13, 1857) was an early leader of the Latter Day Saint movement whose writings became a significant early nineteenth-century exposition of the Latter Day Saint faith. Named in 1835 as one of the first ...

was shot dead in Arkansas by Hector McLean, the estranged husband of Eleanor McLean Pratt, one of Pratt's plural wives. Parley Pratt and Eleanor entered a Celestial marriage (under the theocratic law of the Utah Territory), but Hector had refused Eleanor a divorce. "When she left San Francisco she left Hector, and later she was to state in a court of law that she had left him as a wife the night he drove her from their home. Whatever the legal situation, she thought of herself as an unmarried woman."

Mormon leaders immediately proclaimed Pratt as another martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

, with Brigham Young stating, "Nothing has happened so hard to reconcile my mind to since the death of Joseph." Many Mormons held the people of Arkansas collectively responsible. "It was in accordance with Mormon policy to hold every Arkansan accountable for Pratt's death, just as every Missourian was hated because of the expulsion of the church from that state."

Mormon leaders were teaching that the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messian ...

of Jesus was imminent – "...there are those now living upon the earth who will live to see the consummation" and "...we now bear witness that his coming is near at hand". Based on a somewhat ambiguous statement by Joseph Smith, some Mormons believed that Jesus would return in 1891 and that God would soon exact punishment against the United States for persecuting Mormons and martyring Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Patten and Pratt. In their Endowment ceremony, faithful early Latter-day Saints took an oath

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to g ...

to pray that God would take vengeance against the murderers. As a result of this oath, several Mormon apostles and other leaders considered it their religious duty to kill the prophets' murderers if they ever came across them. The sermons, blessings, and private counsel by Mormon leaders just before the Mountain Meadows massacre can be understood as encouraging private individuals to execute God's judgment against the wicked.

In Cedar City, the teachings of church leaders were particularly strident. Mormons in Cedar City were taught that members should ignore dead bodies and go about their business. Col. William H. Dame, the ranking officer in southern Utah who ordered the Mountain Meadows massacre, received a patriarchal blessing

In the Latter Day Saint movement, a patriarchal blessing (also called an evangelist's blessing) is an ordinance administered by the laying on of hands, with accompanying words of promise, counsel, and lifelong guidance intended solely for the rec ...

in 1854 that he would "be called to act at the head of a portion of thy Brethren and of the Lamanites (Native Americans) in the redemption of Zion and the avenging of the blood of the prophets upon them that dwell on the earth". In June 1857, Philip Klingensmith, another participant, was similarly blessed that he would participate in "avenging the blood of Brother Joseph".

Thus, historians argue that southern Utah Mormons would have been particularly affected by an unsubstantiated rumor that the Baker–Fancher wagon train had been joined by a group of eleven miners and plainsmen who called themselves "Missouri Wildcats", some of whom reportedly taunted, vandalized and "caused trouble" for Mormons and Native Americans along the route (by some accounts claiming that they had the gun that "shot the guts out of Old Joe Smith"). They were also affected by the report to Brigham Young that the Baker–Fancher party was from Arkansas where Pratt was murdered. It was rumored that Pratt's wife recognized some of the Mountain Meadows party as being in the gang that shot and stabbed Pratt.

War hysteria

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events relating to the Utah War, an 1857 deployment toward the Utah Territory of the United States Army, whose arrival was peaceful. In the summer of 1857, however, the Mormons expected an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders and their followers prepared for a siege that could have ended up similar to the seven-year

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events relating to the Utah War, an 1857 deployment toward the Utah Territory of the United States Army, whose arrival was peaceful. In the summer of 1857, however, the Mormons expected an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders and their followers prepared for a siege that could have ended up similar to the seven-year Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

problem occurring at the time. Mormons were required to stockpile grain, and were enjoined against selling grain to emigrants for use as cattle feed. As far-off Mormon colonies retreated, Parowan and Cedar City became isolated and vulnerable outposts. Brigham Young sought to enlist the help of Native American tribes in fighting the "Americans", encouraging them to steal cattle from emigrant trains, and to join Mormons in fighting the approaching army.

Scholars have asserted that George A. Smith's tour of southern Utah influenced the decision to attack and destroy the Fancher–Baker emigrant train near Mountain Meadows, Utah. He met with many of the eventual participants in the massacre, including W. H. Dame, Isaac Haight, John D. Lee and Chief Jackson, leader of a band of Paiutes. He noted that the militia was organized and ready to fight and that some of them were eager to "fight and take vengeance for the cruelties that had been inflicted upon us in the States."

Among Smith's party were a number of Paiute Native American chiefs from the Mountain Meadows area. When Smith returned to Salt Lake, Brigham Young met with these leaders on September 1, 1857, and encouraged them to fight against the Americans in the anticipated clash with the U.S. Army. They were also offered all of the livestock then on the road to California, which included that belonging to the Baker–Fancher party. The Native American chiefs were reluctant, and at least one objected they had previously been told not to steal, and declined the offer.

Brigham Young

There is a consensus among historians that Brigham Young played a role in provoking the massacre, at least unwittingly, and in concealing its evidence after the fact. However, they debate whether Young knew about the planned massacre ahead of time and whether he initially condoned it before later taking a strong public stand against it. Young's use of inflammatory and violent language in response to the Federal expedition added to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. Following the massacre, Young stated in public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Baker–Fancher party. It is unclear whether Young held this view because he believed that this specific group posed an actual threat to colonists or because he believed that the group was directly responsible for past crimes against Mormons. However, in Young's only known correspondence prior to the massacre, he told the Church leaders in Cedar City:

According to historian MacKinnon, "After the tahwar, U.S. President James Buchanan implied that face-to-face communications with Brigham Young might have averted the conflict, and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah could have prevented the Mountain Meadows massacre." MacKinnon suggests that hostilities could have been avoided if Young had traveled east to Washington D.C. to resolve governmental problems instead of taking a five-week trip north on the eve of the Utah War for church related reasons.

A modern forensic assessment of a key affidavit, purportedly given by William Edwards in 1924, has complicated the debate on complicity of senior Mormon leadership in the Mountain Meadows massacre. Analysis indicates that Edwards's signature may have been traced and that the typeset belonged to a typewriter manufactured in the 1950s. The

There is a consensus among historians that Brigham Young played a role in provoking the massacre, at least unwittingly, and in concealing its evidence after the fact. However, they debate whether Young knew about the planned massacre ahead of time and whether he initially condoned it before later taking a strong public stand against it. Young's use of inflammatory and violent language in response to the Federal expedition added to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. Following the massacre, Young stated in public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Baker–Fancher party. It is unclear whether Young held this view because he believed that this specific group posed an actual threat to colonists or because he believed that the group was directly responsible for past crimes against Mormons. However, in Young's only known correspondence prior to the massacre, he told the Church leaders in Cedar City:

According to historian MacKinnon, "After the tahwar, U.S. President James Buchanan implied that face-to-face communications with Brigham Young might have averted the conflict, and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah could have prevented the Mountain Meadows massacre." MacKinnon suggests that hostilities could have been avoided if Young had traveled east to Washington D.C. to resolve governmental problems instead of taking a five-week trip north on the eve of the Utah War for church related reasons.

A modern forensic assessment of a key affidavit, purportedly given by William Edwards in 1924, has complicated the debate on complicity of senior Mormon leadership in the Mountain Meadows massacre. Analysis indicates that Edwards's signature may have been traced and that the typeset belonged to a typewriter manufactured in the 1950s. The Utah State Historical Society

The Utah State Historical Society (USHS), founded in 1897 and now part of the Government of Utah's Division of State History, encourages the research, study, and publication of Utah history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the ...

, which maintains the document in its archives, acknowledges a possible connection to Mark Hofmann, a convicted forger and extortionist, via go-between Lyn Jacobs who provided the society with the document.

Remembrances

The first monument for the victims was built two years after the massacre, by Major Carleton and the U.S. Army. This monument was a simple cairn built over the gravesite of 34 victims, and was topped by a large cedar cross. The monument was found destroyed and the structure was replaced by the U.S. Army in 1864. By some reports, the monument was destroyed in 1861, when Young brought an entourage to Mountain Meadows. Wilford Woodruff, who later became President of the Church, claimed that upon reading the inscription on the cross, which read, "Vengeance is mine, thus saith the Lord. I shall repay", Young responded, "it should be vengeance is mine and I have taken a little." In 1932 residents of the surrounding area constructed a memorial wall around the remnants of the monument. Starting in 1988, the Mountain Meadows Association, composed of descendants of both the Baker–Fancher party victims and the Mormon participants, designed a new monument in the meadows; this monument was completed in 1990 and is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation. In 1999 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints replaced the U.S. Army's cairn and the 1932 memorial wall with a second monument, which it now maintains. In August 1999, when the LDS Church's construction of the 1999 monument had started, the remains of at least 28 massacre victims were dug up by a backhoe. The forensic evidence showed that the remains of the males had been shot by firearms at close range and that the remains of the women and children showed evidence of blunt force trauma.

Starting in 1988, the Mountain Meadows Association, composed of descendants of both the Baker–Fancher party victims and the Mormon participants, designed a new monument in the meadows; this monument was completed in 1990 and is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation. In 1999 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints replaced the U.S. Army's cairn and the 1932 memorial wall with a second monument, which it now maintains. In August 1999, when the LDS Church's construction of the 1999 monument had started, the remains of at least 28 massacre victims were dug up by a backhoe. The forensic evidence showed that the remains of the males had been shot by firearms at close range and that the remains of the women and children showed evidence of blunt force trauma.

In 1955, to memorialize the victims of the massacre, a monument was installed in the town square of

In 1955, to memorialize the victims of the massacre, a monument was installed in the town square of Harrison, Arkansas

Harrison is a city and the county seat of Boone County, Arkansas, United States. It is named after General Marcus LaRue Harrison, a surveyor who laid out the city along Crooked Creek at Stifler Springs. According to 2019 Census Bureau estima ...

. On one side of this monument is a map and short summary of the massacre, while the opposite side contains a list of the victims. In 2005 a replica of the U.S. Army's original 1859 cairn was built in the community of Carrollton, Arkansas

Carrollton is an unincorporated area, unincorporated community in Carroll County, Arkansas, Carroll County, Arkansas, United States. Once designated the county seat, it had a population near the 10,000 mark in the 1850s. It now has 30 residents. I ...

, the former county seat of Carroll County, Arkansas

Carroll County is a county located in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2020 census, the population was 28,260. The county has two county seats, Berryville and Eureka Springs. Carroll County is Arkansas's 26th county, formed on November ...

. it is maintained by the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation.

In 2007, the 150th anniversary of the massacre was remembered by a ceremony held in the meadows. Approximately 400 people, including many descendants of those slain at Mountain Meadows and Elder Henry B. Eyring of the LDS Church's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles attended this ceremony.

In 2011, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

after joint efforts by descendants of those killed and the LDS Church.

In 2014, archaeologist Everett Bassett discovered two rock piles he believes mark additional graves. The locations of the possible graves are on private land and not at any of the monument sites owned by the LDS Church. The Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation has expressed their desire that the sites are conserved and given national monument status. Other descendant groups have been more hesitant in accepting the sites as legitimate grave markers.

Media detailing the massacre

* ''Massacre at Mountain Meadows

''Massacre at Mountain Meadows'' is a book by Latter-day Saint historian Richard E. Turley, Jr. and two Brigham Young University professors of history, Ronald W. Walker and Glen M. Leonard. Leonard was also the director of the Museum of Chur ...

'', by Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, Glen M. Leonard Glen Milton Leonard (born 1938) is an American historian specializing in Mormon history.

Background

Leonard is a native of Farmington, Utah. He received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Utah. For a time he was managing editor of ''U ...

(2008)

* ''House of Mourning: A Biocultural History of the Mountain Meadows Massacre'', by Shannon A. Novak (2008)

* '' Burying The Past: Legacy of The Mountain Meadows Massacre, ''a documentary film by Brian Patrick (2004)

* '' American Massacre: The Tragedy At Mountain Meadows, September 1857'', by Sally Denton (2003)

* ''Blood of the Prophets

''Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows'' (2002) by Will Bagley is a history of the Mountain Meadows massacre. The work updated Juanita Brooks' seminal history '' The Mountain Meadows Massacre'', and remains o ...

: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows'', by Will Bagley

William Grant Bagley (May 27, 1950 – September 28, 2021) was a historian specializing in the history of the Western United States and the American Old West. Bagley wrote about the fur trade, overland emigration, American Indians, military histor ...

(2002)

* '' The Mountain Meadows Massacre'', by Juanita Brooks

Juanita Pulsipher Brooks (January 15, 1898 – August 26, 1989) was an American historian and author, specializing in the American West and Mormon history, including books related to the Mountain Meadows Massacre, to which her grandfather Dudley ...

(1950)

* Mountain Meadows.

' – an article originally published in the Cincinnati Gazette (July 21, 1875), then republished in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat(July 26, 1875). An affidavit of James Lynch's testimony taken in July 1859 about the human remains Lynch saw at Mount Meadows in March and April 1858, about the living conditions of the child survivors of the Massacre during that time, and about the children's statements regarding the perpetrators of the Massacre. Lynch accompanied Dr. Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, on an expedition to the area. The affidavit was given in front of Chief Justice of the Utah Territory Supreme Court Delana R. Eckels on July 27, 1859, and sent by US Army officer S.H. Montgomery to Commissioner of Indian Affairs A.B. Greenwood in August 1859.

Works of historical fiction

* ''September Dawn

''September Dawn'' is a 2007 Canadian-American Western film directed by Christopher Cain, telling a fictional love story against a controversial historical interpretation of the 1857 Mountain Meadows massacre. Written by Cain and Carole Whang Sc ...

'' film by Christopher Cain

Christopher Cain (born October 29, 1943) is an American director, screenwriter, and producer.

Cain was born in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. In 1969, he married Sharon Thomas, and adopted her two sons, Roger and Dean. The couple's daughter Krisin ...

(2007) – The film is a fictional love story between real characters who were involved in the massacre

* ''Red Water'', novel by Judith Freeman (2002) – A novel about how the wives of John D. Lee have to come to terms with their husband's actions

* Under the Banner of Heaven (TV series)

''Under the Banner of Heaven'' is an American true crime drama television miniseries created by Dustin Lance Black based on the nonfiction book of the same name by Jon Krakauer. It premiered on April 28, 2022, on Hulu. Andrew Garfield and Gil B ...

on the historical roots of Mormonism

Mormonism is the religious tradition and theology of the Latter Day Saint movement of Restorationist Christianity started by Joseph Smith in Western New York in the 1820s and 1830s. As a label, Mormonism has been applied to various aspects of ...

* ''Redeye,'' novel by Clyde Edgerton

Clyde Edgerton (born May 20, 1944) is an American author. He has published a dozen books, most of them novels, two of which have been adapted for film. He is also a professor, teaching creative writing.

Biography

Edgerton was born in Durham, N ...

(1995) - A novel about a fictional bounty hunter, Cobb Pittman, who with his catch dog, Redeye, tracks down Mormons responsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

See also

*List of National Historic Landmarks in Utah

__NOTOC__

This is a complete List of National Historic Landmarks in Utah. The United States National Historic Landmark program is operated under the auspices of the National Park Service, and recognizes structures, districts, objects, and similar ...

* National Register of Historic Places listings in Washington County, Utah

* Anti-Mormonism

Anti-Mormonism is discrimination, persecution, hostility or prejudice directed against the Latter Day Saint movement, particularly the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). The term is often used to describe people or literat ...

* Christian terrorism

Christian terrorism, a form of religious terrorism, comprises terrorist acts which are committed by groups or individuals who profess Christian motivations or goals. Christian terrorists justify their violent tactics through their interpretat ...

* Christianity and violence

Christians have had diverse attitudes towards violence and non-violence over time. Both currently and historically, there have been four attitudes towards violence and war and four resulting practices of them within Christianity: non-resistance ...

* Haun's Mill massacre, an attack on Mormons

* History of the Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement is a religious movement within Christianity that arose during the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century and that led to the set of doctrines, practices, and cultures called ''Mormonism'', and to the exi ...

* Missouri Executive Order 44

Missouri Executive Order 44, commonly known as the Mormon Extermination Order, was an executive order issued on October 27, 1838, by the then Governor of Missouri, Lilburn Boggs. The order was issued in the aftermath of the Battle of Crooked Ri ...

* Mormonism and violence

* Salt Creek Canyon massacre

The Salt Creek Canyon massacre occurred on June 4, 1858, when four Danish immigrants were ambushed and killed by unidentified Indians in Salt Creek Canyon, a winding canyon of Salt Creek east of present-day Nephi, in Juab County, Utah.

Massacre ...

* Religious abuse

Religious abuse is abuse administered under the guise of religion, including harassment or humiliation, which may result in psychological trauma. Religious abuse may also include misuse of religion for selfish, secular, or ideological ends such as ...

* Religious terrorism

* Religious violence

Religious violence covers phenomena in which religion is either the subject or the object of violent behavior. All the religions of the world contain narratives, symbols, and metaphors of violence and war. Religious violence is violence th ...

* Religious war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

* Terrorism in the United States

* Domestic terrorism in the United States

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* . * * . * * . * * . * * . * . * * . * . * *scanned versions

. * * * . * * .

published by Mountain Meadows Association * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * .

External links

Mountain Meadows Association

Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation

* ttp://signaturebookslibrary.org/?p=431''The Mountain Meadows Massacre: A Bibliographic Perspective'' by Newell Bringhurst* United States Office of Indian Affairs Papers Relating to Charges Against Jacob Forney. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{Authority control 1857 murders in the United States 1857 in Utah Territory Massacres in 1857 American murder victims Battles involving Native Americans Crimes in Utah Criticism of Mormonism Deaths by firearm in Utah Massacres in the United States Mormonism and Native Americans - Murdered American children Nauvoo Legion Utah War