Magic Lantern on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of

/ref> It was mostly developed in the 17th century and commonly used for entertainment purposes. It was increasingly used for education during the 19th century. Since the late 19th century, smaller versions were also mass-produced as toys. The magic lantern was in wide use from the 18th century until the mid-20th century when it was superseded by a compact version that could hold many 35 mm photographic slides: the

After 1820 the manufacturing of hand colored printed slides started, often making use of

After 1820 the manufacturing of hand colored printed slides started, often making use of

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's book '' Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' included a description of his invention, the "Steganographic Mirror": a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long-distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.

In 1654, Belgian Jesuit mathematician André Tacquet used Kircher's technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionary Martino Martini. Some reports say that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern, which he might have imported from China, but there's no evidence that it used anything other than Kircher's technique. However, Tacquet was a correspondent and friend of

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's book '' Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' included a description of his invention, the "Steganographic Mirror": a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long-distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.

In 1654, Belgian Jesuit mathematician André Tacquet used Kircher's technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionary Martino Martini. Some reports say that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern, which he might have imported from China, but there's no evidence that it used anything other than Kircher's technique. However, Tacquet was a correspondent and friend of

Dutch scientist

Dutch scientist  Christiaan initially referred to the magic lantern as "la lampe" and "la lanterne", but in the last years of his life he used the then common term "laterna magica" in some notes. In 1694, he drew the principle of a "laterna magica" with two lenses.

Christiaan initially referred to the magic lantern as "la lampe" and "la lanterne", but in the last years of his life he used the then common term "laterna magica" in some notes. In 1694, he drew the principle of a "laterna magica" with two lenses.

(–1681), a mathematician from

(–1681), a mathematician from

There are many gaps and uncertainties in the magic lantern's recorded history. A separate early magic lantern tradition seems to have been developed in southern Germany and includes lanterns with horizontal cylindrical bodies, while Walgensten's lantern and probably Huygens' both had vertical bodies. This tradition dates at least to 1671, with the arrival of instrument maker Johann Franz Griendel in the city of

There are many gaps and uncertainties in the magic lantern's recorded history. A separate early magic lantern tradition seems to have been developed in southern Germany and includes lanterns with horizontal cylindrical bodies, while Walgensten's lantern and probably Huygens' both had vertical bodies. This tradition dates at least to 1671, with the arrival of instrument maker Johann Franz Griendel in the city of

One of Christiaan Huygens' contacts imagined how Athanasius Kircher would use the magic lantern: "If he would know about the invention of the Lantern he would surely frighten the cardinals with specters." Kircher would eventually learn about the existence of the magic lantern via Thomas Walgensten and introduced it as "Lucerna Magica" in the widespread 1671 second edition of his book ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae''. Kircher claimed that Thomas Walgensten reworked his ideas from the previous edition of this book into a better lantern. Kircher described this improved lantern, but it was illustrated in a confusing manner: the pictures seem technically incorrect—with both the projected image and the transparencies (H) shown upright (while the text states that they should be inverted), the hollow mirror is too high in one picture and absent in the other, and the lens (I) is at the wrong side of the slide. However, experiments with a construction as illustrated in Kircher's book proved that it could work as a point light-source projection system.

The projected image in one of the illustrations shows a person in purgatory or hellfire and the other depicts Death with a scythe and an hourglass. According to legend Kircher secretly used the lantern at night to project the image of Death on windows of apostates to scare them back into church. Kircher did suggest in his book that an audience would be more astonished by the sudden appearance of images if the lantern would be hidden in a separate room, so the audience would be ignorant of the cause of their appearance.

One of Christiaan Huygens' contacts imagined how Athanasius Kircher would use the magic lantern: "If he would know about the invention of the Lantern he would surely frighten the cardinals with specters." Kircher would eventually learn about the existence of the magic lantern via Thomas Walgensten and introduced it as "Lucerna Magica" in the widespread 1671 second edition of his book ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae''. Kircher claimed that Thomas Walgensten reworked his ideas from the previous edition of this book into a better lantern. Kircher described this improved lantern, but it was illustrated in a confusing manner: the pictures seem technically incorrect—with both the projected image and the transparencies (H) shown upright (while the text states that they should be inverted), the hollow mirror is too high in one picture and absent in the other, and the lens (I) is at the wrong side of the slide. However, experiments with a construction as illustrated in Kircher's book proved that it could work as a point light-source projection system.

The projected image in one of the illustrations shows a person in purgatory or hellfire and the other depicts Death with a scythe and an hourglass. According to legend Kircher secretly used the lantern at night to project the image of Death on windows of apostates to scare them back into church. Kircher did suggest in his book that an audience would be more astonished by the sudden appearance of images if the lantern would be hidden in a separate room, so the audience would be ignorant of the cause of their appearance.

The earliest reports and illustrations of lantern projections suggest that they were all intended to scare the audience. Pierre Petit called the apparatus "lanterne de peur" (lantern of fear) in his 1664 letter to Huygens. Surviving lantern plates and descriptions from the next decades prove that the new medium was not just used for horror shows, but that many kinds of subjects were projected. Griendel didn't mention scary pictures when he described the magic lantern to

The earliest reports and illustrations of lantern projections suggest that they were all intended to scare the audience. Pierre Petit called the apparatus "lanterne de peur" (lantern of fear) in his 1664 letter to Huygens. Surviving lantern plates and descriptions from the next decades prove that the new medium was not just used for horror shows, but that many kinds of subjects were projected. Griendel didn't mention scary pictures when he described the magic lantern to

The magic lantern was not only a direct ancestor of the motion picture projector as a means for visual storytelling, but it could itself be used to project moving images. Some suggestion of movement could be achieved by alternating between pictures of different phases of a motion, but most magic lantern "animations" used two glass slides projected together — one with the stationary part of the picture and the other with the part that could be set in motion by hand or by a simple mechanism.

Motion in animated slides was mostly limited to either two phases of a movement or transformation, or a more gradual singular movement (e.g., a train passing through a landscape). These limitations made subjects with repetitive movements popular, like the sails on a windmill turning around or children on a seesaw. Movements could be repeated over and over and could be performed at different speeds. A common technique that is comparable to the effect of a panning camera makes use of a long slide that is simply pulled slowly through the lantern and usually shows a landscape, sometimes with several phases of a story within the continuous backdrop.

Movement of projected images was also possible by moving the magic lantern itself. This became a staple technique in phantasmagoria shows in the late 18th century, often with the lantern sliding on rails or riding on small wheels and hidden from the view of the audience behind the projection screen.

The magic lantern was not only a direct ancestor of the motion picture projector as a means for visual storytelling, but it could itself be used to project moving images. Some suggestion of movement could be achieved by alternating between pictures of different phases of a motion, but most magic lantern "animations" used two glass slides projected together — one with the stationary part of the picture and the other with the part that could be set in motion by hand or by a simple mechanism.

Motion in animated slides was mostly limited to either two phases of a movement or transformation, or a more gradual singular movement (e.g., a train passing through a landscape). These limitations made subjects with repetitive movements popular, like the sails on a windmill turning around or children on a seesaw. Movements could be repeated over and over and could be performed at different speeds. A common technique that is comparable to the effect of a panning camera makes use of a long slide that is simply pulled slowly through the lantern and usually shows a landscape, sometimes with several phases of a story within the continuous backdrop.

Movement of projected images was also possible by moving the magic lantern itself. This became a staple technique in phantasmagoria shows in the late 18th century, often with the lantern sliding on rails or riding on small wheels and hidden from the view of the audience behind the projection screen.

Various types of mechanisms were commonly used to add movement to the projected image:

*slipping slides: a movable glass plate with one or more figures (or any part of a picture for which movement was desired) was slipped over a stationary one, directly by hand or with a small drawbar (see: Fig. 7 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a tightrope walker sliding across the rope). A common example showed a creature that could move the pupils in its eyes, as if looking in all directions. A long piece of glass could show a procession of figures, or a train with several wagons. Quite convincing illusions of moving waves on a sea or lake have also been achieved with this method.

*slipping slides with masking: black paint on portions of the moving plate would mask parts of the underlying image — with a black background — on the stationary glass. This made it possible to hide and then reveal the previous position of a part, for instance a limb, to suggest repetitious movement. The suggested movement would be rather jerky and usually operated quickly. Masking in slides was also often used to create change rather than movement (see: Fig. 6 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a man, his wig and his hat): for instance a person's head could be replaced with that of an animal. More gradual and natural movement was also possible; for instance to make a nose grow very long by slowly moving a masking glass.

*lever slides: the moving part was operated by a lever. These could show a more natural movement than slipping slides and were mostly used for repetitive movements, for instance a woodcutter raising and lowering his axe, or a girl on a swing. (see: Fig. 5 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a drinking man raising and lowering his glass + Fig. 8: a lady curtsying)

*pulley slides: a pulley rotates the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill (see: fig. 4 on illustration by Van Musschenbroek)

*rack and pinion slides: turning the handle of a rackwork would rotate or lift the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill or for having a hot air balloon take off and descend. A more complex astronomical rackwork slide showed the planets and their satellites orbiting around the sun.

*fantoccini slides: jointed figures set in motion by levers, thin rods, or cams and worm wheels. A popular version had a somersaulting monkey with arms attached to mechanism that made it tumble with dangling feet. Named after the Italian word for animated puppets, like marionettes or jumping jacks. Two different British patents for slides with moving jointed figures were granted in 1891.

*a snow effect slide can add snow to another slide (preferably of a winter scene) by moving a flexible loop of material pierced with tiny holes in front of one of the lenses of a double or triple lantern.

Mechanical slides with abstract special effects include:

Various types of mechanisms were commonly used to add movement to the projected image:

*slipping slides: a movable glass plate with one or more figures (or any part of a picture for which movement was desired) was slipped over a stationary one, directly by hand or with a small drawbar (see: Fig. 7 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a tightrope walker sliding across the rope). A common example showed a creature that could move the pupils in its eyes, as if looking in all directions. A long piece of glass could show a procession of figures, or a train with several wagons. Quite convincing illusions of moving waves on a sea or lake have also been achieved with this method.

*slipping slides with masking: black paint on portions of the moving plate would mask parts of the underlying image — with a black background — on the stationary glass. This made it possible to hide and then reveal the previous position of a part, for instance a limb, to suggest repetitious movement. The suggested movement would be rather jerky and usually operated quickly. Masking in slides was also often used to create change rather than movement (see: Fig. 6 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a man, his wig and his hat): for instance a person's head could be replaced with that of an animal. More gradual and natural movement was also possible; for instance to make a nose grow very long by slowly moving a masking glass.

*lever slides: the moving part was operated by a lever. These could show a more natural movement than slipping slides and were mostly used for repetitive movements, for instance a woodcutter raising and lowering his axe, or a girl on a swing. (see: Fig. 5 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a drinking man raising and lowering his glass + Fig. 8: a lady curtsying)

*pulley slides: a pulley rotates the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill (see: fig. 4 on illustration by Van Musschenbroek)

*rack and pinion slides: turning the handle of a rackwork would rotate or lift the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill or for having a hot air balloon take off and descend. A more complex astronomical rackwork slide showed the planets and their satellites orbiting around the sun.

*fantoccini slides: jointed figures set in motion by levers, thin rods, or cams and worm wheels. A popular version had a somersaulting monkey with arms attached to mechanism that made it tumble with dangling feet. Named after the Italian word for animated puppets, like marionettes or jumping jacks. Two different British patents for slides with moving jointed figures were granted in 1891.

*a snow effect slide can add snow to another slide (preferably of a winter scene) by moving a flexible loop of material pierced with tiny holes in front of one of the lenses of a double or triple lantern.

Mechanical slides with abstract special effects include:

*the Chromatrope: a slide that produces dazzling colorful geometrical patterns by rotating two painted glass discs in opposite directions, originally with a double pulley mechanism but later usually with a rackwork mechanism. It was possibly invented around 1844 by English glass painter and showman Henry Langdon Childe and soon added as a novelty to the program of the Royal Polytechnic Institution.

*the Astrometeoroscope or Astrometroscope: a large slide that projected a lacework of dots forming constantly changing geometrical line patterns, compared with stars and meteors. It was invented in or before 1858 by the Hungarian engineer S. Pilcher and used a very ingenious mechanism with two metal plates obliquely crossed with slits that moved to and fro in contrary directions. Except for when the only known example was used in a performance, it was kept locked away at the Polytechnic so no one could discover the secret technique. When the Polytechnic auctioned the device, Picher eventually paid an extravagant price for his own invention to keep its workings secret.

*the Eidotrope: counter-rotating discs of perforated metal or card (or wire gauze or lace), producing swirling Moiré patterns of bright white dots. It was invented by English scientist Charles Wheatstone in 1866.

*the Kaleidotrope: a slide with a single perforated metal or cardboard disc suspended on a spiral spring. The holes can be tinted with colored pieces of gelatin. When struck the disc's vibration and rotation sends the colored dots of light swirling around in all sorts of shapes and patterns. The device was demonstrated at the Royal Polytechnic Institution around 1870 and dubbed "Kaleidotrope" when commercial versions were marketed.

*the Cycloidotrope (circa 1865): a slide with an adjustable stylus bar for drawing geometric patterns on sooty glass when hand cranked during projection. The patterns are similar to that produced with a Spirograph.

*a Newton colour wheel slide that, when spinning fast enough, blends seven colours into a white circle

*the Chromatrope: a slide that produces dazzling colorful geometrical patterns by rotating two painted glass discs in opposite directions, originally with a double pulley mechanism but later usually with a rackwork mechanism. It was possibly invented around 1844 by English glass painter and showman Henry Langdon Childe and soon added as a novelty to the program of the Royal Polytechnic Institution.

*the Astrometeoroscope or Astrometroscope: a large slide that projected a lacework of dots forming constantly changing geometrical line patterns, compared with stars and meteors. It was invented in or before 1858 by the Hungarian engineer S. Pilcher and used a very ingenious mechanism with two metal plates obliquely crossed with slits that moved to and fro in contrary directions. Except for when the only known example was used in a performance, it was kept locked away at the Polytechnic so no one could discover the secret technique. When the Polytechnic auctioned the device, Picher eventually paid an extravagant price for his own invention to keep its workings secret.

*the Eidotrope: counter-rotating discs of perforated metal or card (or wire gauze or lace), producing swirling Moiré patterns of bright white dots. It was invented by English scientist Charles Wheatstone in 1866.

*the Kaleidotrope: a slide with a single perforated metal or cardboard disc suspended on a spiral spring. The holes can be tinted with colored pieces of gelatin. When struck the disc's vibration and rotation sends the colored dots of light swirling around in all sorts of shapes and patterns. The device was demonstrated at the Royal Polytechnic Institution around 1870 and dubbed "Kaleidotrope" when commercial versions were marketed.

*the Cycloidotrope (circa 1865): a slide with an adjustable stylus bar for drawing geometric patterns on sooty glass when hand cranked during projection. The patterns are similar to that produced with a Spirograph.

*a Newton colour wheel slide that, when spinning fast enough, blends seven colours into a white circle

The effect of a gradual transition from one image to another, known as a dissolve in modern filmmaking, became the basis of a popular type of magic lantern show in England in the 19th century. Typical dissolving views showed landscapes dissolving from day to night or from summer to winter. This was achieved by aligning the projection of two matching images and slowly diminishing the first image while introducing the second image. The subject and the effect of magic lantern dissolving views is similar to the popular

The effect of a gradual transition from one image to another, known as a dissolve in modern filmmaking, became the basis of a popular type of magic lantern show in England in the 19th century. Typical dissolving views showed landscapes dissolving from day to night or from summer to winter. This was achieved by aligning the projection of two matching images and slowly diminishing the first image while introducing the second image. The subject and the effect of magic lantern dissolving views is similar to the popular

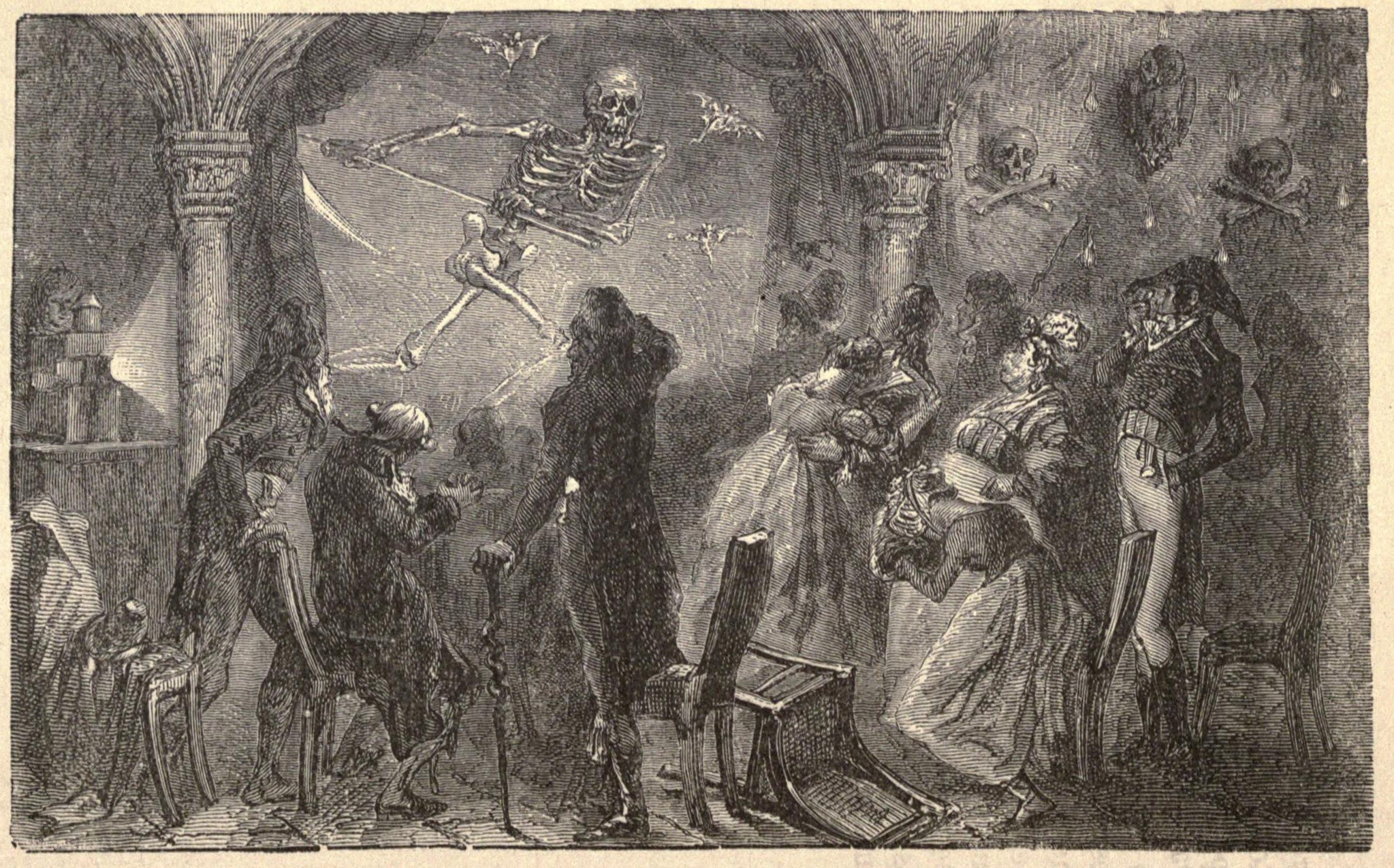

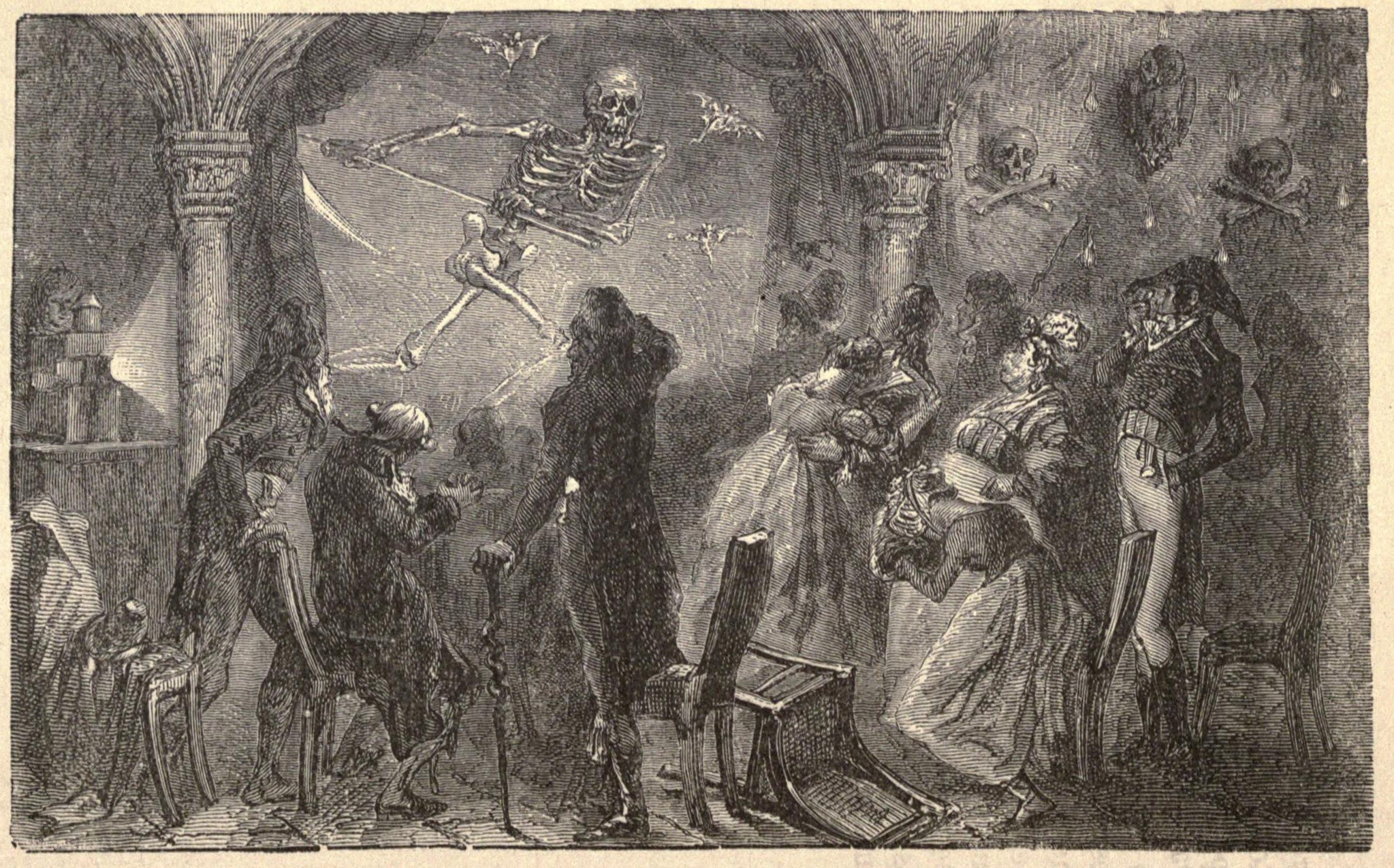

Phantasmagoria was a form of horror theater that used one or more magic lanterns to project frightening images, especially of ghosts. Showmen used rear projection, mobile or portable projectors and a variety of effects to produce convincing necromantic experiences. It was very popular in Europe from the late 18th century to well into the 19th century.

It is thought that optical devices like concave mirrors and the camera obscura have been used since antiquity to fool spectators into believing they saw real gods and spirits, but it was the magician "physicist" Phylidor who created what must have been the first true phantasmagoria show. He probably used mobile magic lanterns with the recently invented Argand lamp to create his successful (Schröpfer-esque and Cagiostro-esque Ghost Apparitions) in Vienna from 1790 to 1792. Phylidor stated that his show of perfected apparitions revealed how charlatans like Johann Georg Schröpfer and Cagliostro had fooled their audiences. As "Paul Filidort," he presented his ''Phantasmagorie'' in Paris From December 1792 to July 1793, probably using that term for the first time. As "Paul de Philipsthal," he performed ''Phantasmagoria'' shows in Britain beginning in 1801 with great success.

One of many showmen who were inspired by Phylidor, Etienne-Gaspard Robert became very famous with his own ''Fantasmagorie'' show in Paris from 1798 to 1803 (later performing throughout Europe and returning to Paris for a triumphant comeback in Paris in 1814). He patented a mobile "Fantascope" lantern in 1798.

Phantasmagoria was a form of horror theater that used one or more magic lanterns to project frightening images, especially of ghosts. Showmen used rear projection, mobile or portable projectors and a variety of effects to produce convincing necromantic experiences. It was very popular in Europe from the late 18th century to well into the 19th century.

It is thought that optical devices like concave mirrors and the camera obscura have been used since antiquity to fool spectators into believing they saw real gods and spirits, but it was the magician "physicist" Phylidor who created what must have been the first true phantasmagoria show. He probably used mobile magic lanterns with the recently invented Argand lamp to create his successful (Schröpfer-esque and Cagiostro-esque Ghost Apparitions) in Vienna from 1790 to 1792. Phylidor stated that his show of perfected apparitions revealed how charlatans like Johann Georg Schröpfer and Cagliostro had fooled their audiences. As "Paul Filidort," he presented his ''Phantasmagorie'' in Paris From December 1792 to July 1793, probably using that term for the first time. As "Paul de Philipsthal," he performed ''Phantasmagoria'' shows in Britain beginning in 1801 with great success.

One of many showmen who were inspired by Phylidor, Etienne-Gaspard Robert became very famous with his own ''Fantasmagorie'' show in Paris from 1798 to 1803 (later performing throughout Europe and returning to Paris for a triumphant comeback in Paris in 1814). He patented a mobile "Fantascope" lantern in 1798.

magic-lantern.eu

website with more than 8000 lantern slides online

Joseph Boggs Beale Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center

Cinema and its Ancestors: The Magic of Motion

Video interview with Tom Gunning

nbsp;– feat. Pierre Albanese and Thomas Bloch

Live Magic Lantern Shows

The American Magic Lantern Theater

Magic Lantern – A School of Cinema

Film Institute Chennai

LUCERNA - The Magic Lantern Web Resource

The Magic Lantern Society

An introduction to lantern history featuring images of lanterns, slides, and lantern accessories

Joseph Boggs Beale collection of magic lantern illustrations

Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Images of Lantern Slides from the National Museum of Australia

The Magic Lantern Society, United Kingdom

at the New-York Historical Society

Lantern Slide Collection

at

W. Ward Marsh

Collection. {{DEFAULTSORT:Magic Lantern Display technology Optical toys History of film Precursors of photography Italian inventions

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector

A projector or image projector is an optical device that projects an image (or moving images) onto a surface, commonly a projection screen. Most projectors create an image by shining a light through a small transparent lens, but some newer typ ...

that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photograph

A photograph (also known as a photo, image, or picture) is an image created by light falling on a photosensitive surface, usually photographic film or an electronic image sensor, such as a CCD or a CMOS chip. Most photographs are now create ...

s—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a single lens inverts an image projected through it (as in the phenomenon which inverts the image of a camera obscura), slides were inserted upside down in the magic lantern, rendering the projected image correctly oriented."Erecting the inverted image In the magic lantern", Henry Morton, Ph.D., ''Journal of the Franklin Institute'', Volume 83, Issue 6, June 1867, Pages 406-409; "A lens, as every one knows, inverts the image which it makes of any object; hence, in the magic lantern, we insert the image upside down."/ref> It was mostly developed in the 17th century and commonly used for entertainment purposes. It was increasingly used for education during the 19th century. Since the late 19th century, smaller versions were also mass-produced as toys. The magic lantern was in wide use from the 18th century until the mid-20th century when it was superseded by a compact version that could hold many 35 mm photographic slides: the

slide projector

A slide projector is an opto-mechanical device for showing photographic slides.

35 mm slide projectors, direct descendants of the larger-format magic lantern, first came into widespread use during the 1950s as a form of occasional hom ...

.

Technology

Apparatus

The magic lantern used a concave mirror behind a light source to direct the light through a small rectangular sheet of glass—a "lantern slide" that bore the image—and onward into a lens at the front of the apparatus. The lens adjusted to focus the plane of the slide at the distance of the projection screen, which could be simply a white wall, and it therefore formed an enlarged image of the slide on the screen.Pfragner, Julius. "An Optician Looks for Work". The Motion Picture: From Magic Lantern to Sound. Great Britain: Bailey Brothers and Swinfen Ltd. 9-21. Print. Some lanterns, including those ofChristiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

and Jan van Musschenbroek, used three lenses for the objective.

Biunial lanterns, with two objectives, became common during the 19th century and enabled a smooth and easy change of pictures. Stereopticons added more powerful light sources to optimize the projection of photographic slides.

Slides

Originally the pictures were hand painted on glass slides. Initially, figures were rendered with black paint but soon transparent colors were also used. Sometimes the painting was done on oiled paper. Usually black paint was used as a background to block superfluous light, so the figures could be projected without distracting borders or frames. Many slides were finished with a layer of transparent lacquer, but in a later period cover glasses were also used to protect the painted layer. Most handmade slides were mounted in wood frames with a round or square opening for the picture.decalcomania

Decalcomania (from french: décalcomanie) is a decorative technique by which engravings and prints may be transferred to pottery or other materials.

A shortened version of the term is used for a mass-produced commodity art transfer or product l ...

transfers. Many manufactured slides were produced on strips of glass with several pictures on them and rimmed with a strip of glued paper.

The first photographic lantern slides, called ''hyalotypes'', were invented by the German-born brothers Ernst Wilhelm (William) and Friedrich (Frederick) Langenheim in 1848 in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

and patented in 1850.

Light sources

Apart from sunlight, the only light sources available at the time of invention in the 17th century were candles and oil lamps, which were very inefficient and produced very dim projected images. The invention of the Argand lamp in the 1790s helped to make the images brighter. The invention oflimelight

Limelight (also known as Drummond light or calcium light)James R. Smith (2004). ''San Francisco's Lost Landmarks'', Quill Driver Books. is a type of stage lighting once used in theatres and music halls. An intense illumination is created whe ...

in the 1820s made them even brighter. The invention of the intensely bright electric arc lamp

An arc lamp or arc light is a lamp that produces light by an electric arc (also called a voltaic arc).

The carbon arc light, which consists of an arc between carbon electrodes in air, invented by Humphry Davy in the first decade of the 1800s, ...

in the 1860s eliminated the need for combustible gases or hazardous chemicals, and eventually the incandescent electric lamp further improved safety and convenience, although not brightness.Waddington, Damer. "Introduction". Panoramas, Magic Lanterns and Cinemas. Channel Islands, NJ: Tocan Books. xiii-xv. Print.

Precursors

Several types of projection systems existed before the invention of the magic lantern. Giovanni Fontana,Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

and Cornelis Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel ( ) (1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, op ...

described or drew image projectors that had similarities to the magic lantern. In the 17th century, there was an immense interest in optics. The telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

and microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

were invented (in 1608 and the 1620s respectively) and apart from being useful to some scientists, such instruments were especially popular as entertaining curiosities to people who could afford them. The magic lantern would prove a nautral successor.

Camera obscura

The magic lantern can be seen as a further development of camera obscura. This is a natural phenomenon that occurs when an image of a scene at the other side of a screen (for instance a wall) is projected through a small hole in that screen as an inverted image (left to right and upside down) on a surface opposite to the opening. It was known at least since the 5th century BC and experimented with in darkened rooms at least since . The use of a lens in the hole has been traced back to . The portable camera obscura box with a lens was developed in the 17th century. Dutch inventorCornelis Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel ( ) (1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, op ...

is thought to have sold one to Dutch poet, composer and diplomat Constantijn Huygens in 1622, while the oldest known clear description of a box-type camera is in German Jesuit scientist Gaspar Schott's 1657 book ''Magia universalis naturæ et artis''.

Steganographic mirror

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's book '' Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' included a description of his invention, the "Steganographic Mirror": a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long-distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.

In 1654, Belgian Jesuit mathematician André Tacquet used Kircher's technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionary Martino Martini. Some reports say that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern, which he might have imported from China, but there's no evidence that it used anything other than Kircher's technique. However, Tacquet was a correspondent and friend of

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's book '' Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' included a description of his invention, the "Steganographic Mirror": a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long-distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.

In 1654, Belgian Jesuit mathematician André Tacquet used Kircher's technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionary Martino Martini. Some reports say that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern, which he might have imported from China, but there's no evidence that it used anything other than Kircher's technique. However, Tacquet was a correspondent and friend of Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

and may thus have been a very early adapter of the magic lantern technique that Huygens developed around this period.

Invention

Christiaan Huygens

Dutch scientist

Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

is considered as one of the possible inventors of the magic lantern. He knew Athanasius Kircher's 1645 edition of ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae'' which described a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight. Christiaan's father Constantijn had been acquainted with Cornelis Drebbel who used some unidentified optical techniques to transform himself and to summon appearances in magical performances. Constantijn Huygens wrote about a camera obscura device that he got from Drebbel in 1622.

The oldest known document concerning the magic lantern is a page on which Christiaan Huygens made ten small sketches of a skeleton taking off its skull, above which he wrote "for representations by means of convex glasses with the lamp" (translated from French). As this page was found between documents dated in 1659, it is believed to have been made in the same year. Huygens soon seemed to regret this invention, as he thought it was too frivolous. In a 1662 letter to his brother Lodewijk

Lodewijk () is the Dutch name for Louis. In specific it may refer to:

Given name Literature

* Lodewijk Hartog van Banda (1916–2006), Dutch comic strip writer

* Lodewijk Paul Aalbrecht Boon, (1912-1979) Flemish writer

* Lodewijk van Deysse ...

he claimed he thought of it as some old "bagatelle" and seemed convinced that it would harm the family's reputation if people found out the lantern came from him. Christiaan had reluctantly sent a lantern to their father, but when he realized that Constantijn intended to show the lantern to the court of King Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

at the Louvre, Christiaan asked Lodewijk to sabotage the lantern.

Christiaan initially referred to the magic lantern as "la lampe" and "la lanterne", but in the last years of his life he used the then common term "laterna magica" in some notes. In 1694, he drew the principle of a "laterna magica" with two lenses.

Christiaan initially referred to the magic lantern as "la lampe" and "la lanterne", but in the last years of his life he used the then common term "laterna magica" in some notes. In 1694, he drew the principle of a "laterna magica" with two lenses.

Walgensten, the Dane

(–1681), a mathematician from

(–1681), a mathematician from Gotland

Gotland (, ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a province, county, municipality, and diocese. The province includes the islands of Fårö and Gotska Sandön to ...

, studied at the university of Leiden

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, as a reward to the city of Le ...

in 1657–58. He possibly met Christiaan Huygens during this time (and/or on several other occasions) and may have learned about the magic lantern from him. Correspondence between them is known from 1667. At least from 1664 until 1670, Walgensten demonstrated the magic lantern in Paris (1664), Lyon (1665), Rome (1665–1666), and Copenhagen (1670). He "sold such lanterns to different Italian princes in such an amount that they now are almost everyday items in Rome", according to Athanasius Kircher in 1671. In 1670, Walgensten projected an image of Death at the court of King Frederick III of Denmark. This scared some courtiers, but the king dismissed their cowardice and requested to repeat the figure three times. The king died a few days later. After Walgensten died, his widow sold his lanterns to the , but they have not been preserved. Walgensten is credited with coining the term ''Laterna Magica'', assuming he communicated this name to Claude Dechales who, in 1674, published about seeing the machine of the "erudite Dane" in 1665 in Lyon.

Possible German origins: Wiesel and Griendel

There are many gaps and uncertainties in the magic lantern's recorded history. A separate early magic lantern tradition seems to have been developed in southern Germany and includes lanterns with horizontal cylindrical bodies, while Walgensten's lantern and probably Huygens' both had vertical bodies. This tradition dates at least to 1671, with the arrival of instrument maker Johann Franz Griendel in the city of

There are many gaps and uncertainties in the magic lantern's recorded history. A separate early magic lantern tradition seems to have been developed in southern Germany and includes lanterns with horizontal cylindrical bodies, while Walgensten's lantern and probably Huygens' both had vertical bodies. This tradition dates at least to 1671, with the arrival of instrument maker Johann Franz Griendel in the city of Nürnberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, which Johann Zahn identified as one of the centers of magic lantern production in 1686. Griendel was indicated as the inventor of the magic lantern by Johann Christoph Kohlhans in a 1677 publication. It has been suggested that this tradition is older and that instrument maker Johann Wiesel (1583–1662) from Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

may have been making magic lanterns earlier on and possibly inspired Griendel and even Huygens. Huygens is known to have studied samples of Wiesel's lens-making and instruments since 1653. Wiesel did make a ship's lantern around 1640 that has much in common with the magic lantern design that Griendel would later apply: a horizontal cylindrical body with a rosette chimney on top, a concave mirror behind a fixture for a candle or lamp inside and a biconvex lens at the front. There is no evidence that Wiesel actually ever made a magic lantern, but in 1674, his successor offered a variety of magic lanterns from the same workshop. This successor is thought to have only continued producing Wiesel's designs after his death in 1662, without adding anything new.

Further history

Early adopters

Before 1671, only a small circle of people seemed to have knowledge of the magic lantern, and almost every known report of the device from this period had to do with people that were more or less directly connected to Christiaan Huygens. Despite the rejection expressed in his letters to his brother, Huygens must have familiarized several people with the lantern. In 1664 Parisian engineerPierre Petit Pierre Petit may refer to:

* Pierre Petit (engineer) (1594–1677), French military engineer, mathematician, and physicist

* Pierre Petit (scholar) (1617–1687), French poet, doctor, and classicist

* Pierre Petit (photographer) (1832–1909), Fr ...

wrote to Huygens to ask for some specifications of the lantern, because he was trying to construct one after seeing the lantern of "the dane" (probably Walgensten). The lantern that Petit was constructing had a concave mirror behind the lamp. This directed more light through the lens, resulting in a brighter projection, and it would become a standard part of most of the lanterns that were made later. Petit may have copied it from Walgensten, but he expressed that he made a lamp stronger than any he had ever seen..

Starting in 1661, Huygens corresponded with London optical instrument-maker Richard Reeve. Reeve was soon selling magic lanterns, demonstrated one in his shop on 17 May 1663 to Balthasar de Monconys

Balthasar de Monconys (1611–1665) was a French traveller, diplomat, physicist and magistrate, who left a diary, which was published by his son as ''Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, Conseiller du Roy en ses Conseils d’Estat & Privé ...

, and sold one to Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

in August 1666.

One of Christiaan Huygens' contacts imagined how Athanasius Kircher would use the magic lantern: "If he would know about the invention of the Lantern he would surely frighten the cardinals with specters." Kircher would eventually learn about the existence of the magic lantern via Thomas Walgensten and introduced it as "Lucerna Magica" in the widespread 1671 second edition of his book ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae''. Kircher claimed that Thomas Walgensten reworked his ideas from the previous edition of this book into a better lantern. Kircher described this improved lantern, but it was illustrated in a confusing manner: the pictures seem technically incorrect—with both the projected image and the transparencies (H) shown upright (while the text states that they should be inverted), the hollow mirror is too high in one picture and absent in the other, and the lens (I) is at the wrong side of the slide. However, experiments with a construction as illustrated in Kircher's book proved that it could work as a point light-source projection system.

The projected image in one of the illustrations shows a person in purgatory or hellfire and the other depicts Death with a scythe and an hourglass. According to legend Kircher secretly used the lantern at night to project the image of Death on windows of apostates to scare them back into church. Kircher did suggest in his book that an audience would be more astonished by the sudden appearance of images if the lantern would be hidden in a separate room, so the audience would be ignorant of the cause of their appearance.

One of Christiaan Huygens' contacts imagined how Athanasius Kircher would use the magic lantern: "If he would know about the invention of the Lantern he would surely frighten the cardinals with specters." Kircher would eventually learn about the existence of the magic lantern via Thomas Walgensten and introduced it as "Lucerna Magica" in the widespread 1671 second edition of his book ''Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae''. Kircher claimed that Thomas Walgensten reworked his ideas from the previous edition of this book into a better lantern. Kircher described this improved lantern, but it was illustrated in a confusing manner: the pictures seem technically incorrect—with both the projected image and the transparencies (H) shown upright (while the text states that they should be inverted), the hollow mirror is too high in one picture and absent in the other, and the lens (I) is at the wrong side of the slide. However, experiments with a construction as illustrated in Kircher's book proved that it could work as a point light-source projection system.

The projected image in one of the illustrations shows a person in purgatory or hellfire and the other depicts Death with a scythe and an hourglass. According to legend Kircher secretly used the lantern at night to project the image of Death on windows of apostates to scare them back into church. Kircher did suggest in his book that an audience would be more astonished by the sudden appearance of images if the lantern would be hidden in a separate room, so the audience would be ignorant of the cause of their appearance.

Educational use and other subjects

The earliest reports and illustrations of lantern projections suggest that they were all intended to scare the audience. Pierre Petit called the apparatus "lanterne de peur" (lantern of fear) in his 1664 letter to Huygens. Surviving lantern plates and descriptions from the next decades prove that the new medium was not just used for horror shows, but that many kinds of subjects were projected. Griendel didn't mention scary pictures when he described the magic lantern to

The earliest reports and illustrations of lantern projections suggest that they were all intended to scare the audience. Pierre Petit called the apparatus "lanterne de peur" (lantern of fear) in his 1664 letter to Huygens. Surviving lantern plates and descriptions from the next decades prove that the new medium was not just used for horror shows, but that many kinds of subjects were projected. Griendel didn't mention scary pictures when he described the magic lantern to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ...

in December 1671: "An optical lantern which presents everything that one desires, figures, paintings, portraits, faces, hunts, even an entire comedy with all its lively colours." In 1675, Leibniz saw an important role for the magic lantern in his plan for a kind of world exhibition with projections of "attempts at flight, artistic meteors, optical effects, representations of the sky with the star and comets, and a model of the earth (...), fireworks, water fountains, and ships in rare forms; then mandrakes and other rare plants and exotic animals." In 1685–1686, Johannes Zahn was an early advocate for use of the device for educational purposes: detailed anatomical illustrations were difficult to draw on a chalkboard, but could easily be copied onto glass or mica.

By the 1730s the use of magic lanterns started to become more widespread when travelling showmen, conjurers and storytellers added them to their repertoire. The travelling lanternists were often called Savoyards (they supposedly came from the Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Sa ...

region in France) and became a common sight in many European cities.

In France in the 1770s François Dominique Séraphin used magic lanterns to perform his "Ombres Chinoises" (Chinese shadows), a form of shadow play

Shadow play, also known as shadow puppetry, is an ancient form of storytelling and entertainment which uses flat articulated cut-out figures (shadow puppets) which are held between a source of light and a translucent screen or scrim. The cut-ou ...

.

Magic lanterns had also become a staple of science lecturing and museum events since Scottish lecturer Henry Moyes's tour of America in 1785–86, when he recommended that all college laboratories procure one. French writer and educator Stéphanie Félicité, comtesse de Genlis

Caroline-Stéphanie-Félicité, Madame de Genlis (25 January 174631 December 1830) was a French writer of the late 18th and early 19th century, known for her novels and theories of children's education. She is now best remembered for her journal ...

popularized the use of magic lanterns as an educational tool in the late 1700s when using projected images of plants to teach botany. Her educational methods were published in America in English translation during the early 1820s.

A type of lantern was constructed by Moses Holden between 1814 and 1815 for illustrating his astronomical lectures.

Mass slide production

In 1821, Philip Carpenter's London company, which becameCarpenter and Westley

Carpenter and Westley were a British optical, mathematical and scientific instrument makers between 1808 and 1914. The company was founded by Philip Carpenter (18 November 1776, Kidderminster – 20 April 1833, London)Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

. The same year many other slides appeared in the company's catalogue: "The Kings and Queens of England" (9 sliders taken from David Hume's History of England), "Astronomical Diagrams and Constellations" (9 sliders taken from Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel's textbooks), "Views and Buildings", Ancient and Modern Costume (62 sliders from various sources). Fifteen sliders of the category "Humorous" provided some entertainment, but the focus on education was obvious and very successful.

Through the mid-19th century, the market for magic lanterns was concentrated in Europe with production focused primarily on Italy, France, and England. In 1848, a New York optician began advertising imported slides and locally produced magic lanterns. By 1860, however, mass production began to make magic lanterns more widely available and affordable, with much of the production in the latter half of the 19th century concentrated in Germany. These smaller lanterns had smaller glass sliders, which instead of wooden frames usually had colorful strips of paper glued around their edges with the images printed directly on the glass.

Waning popularity

The popularity of magic lanterns waned after the introduction ofmovies

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmospher ...

in the 1890s, but they remained a common medium until slide projector

A slide projector is an opto-mechanical device for showing photographic slides.

35 mm slide projectors, direct descendants of the larger-format magic lantern, first came into widespread use during the 1950s as a form of occasional hom ...

s became widespread during the 1950s.

Moving images

The magic lantern was not only a direct ancestor of the motion picture projector as a means for visual storytelling, but it could itself be used to project moving images. Some suggestion of movement could be achieved by alternating between pictures of different phases of a motion, but most magic lantern "animations" used two glass slides projected together — one with the stationary part of the picture and the other with the part that could be set in motion by hand or by a simple mechanism.

Motion in animated slides was mostly limited to either two phases of a movement or transformation, or a more gradual singular movement (e.g., a train passing through a landscape). These limitations made subjects with repetitive movements popular, like the sails on a windmill turning around or children on a seesaw. Movements could be repeated over and over and could be performed at different speeds. A common technique that is comparable to the effect of a panning camera makes use of a long slide that is simply pulled slowly through the lantern and usually shows a landscape, sometimes with several phases of a story within the continuous backdrop.

Movement of projected images was also possible by moving the magic lantern itself. This became a staple technique in phantasmagoria shows in the late 18th century, often with the lantern sliding on rails or riding on small wheels and hidden from the view of the audience behind the projection screen.

The magic lantern was not only a direct ancestor of the motion picture projector as a means for visual storytelling, but it could itself be used to project moving images. Some suggestion of movement could be achieved by alternating between pictures of different phases of a motion, but most magic lantern "animations" used two glass slides projected together — one with the stationary part of the picture and the other with the part that could be set in motion by hand or by a simple mechanism.

Motion in animated slides was mostly limited to either two phases of a movement or transformation, or a more gradual singular movement (e.g., a train passing through a landscape). These limitations made subjects with repetitive movements popular, like the sails on a windmill turning around or children on a seesaw. Movements could be repeated over and over and could be performed at different speeds. A common technique that is comparable to the effect of a panning camera makes use of a long slide that is simply pulled slowly through the lantern and usually shows a landscape, sometimes with several phases of a story within the continuous backdrop.

Movement of projected images was also possible by moving the magic lantern itself. This became a staple technique in phantasmagoria shows in the late 18th century, often with the lantern sliding on rails or riding on small wheels and hidden from the view of the audience behind the projection screen.

History

In 1645, Kircher had already suggested projecting live insects and shadow puppets from the surface of the mirror in his Steganographic system to perform dramatic scenes. Christiaan Huygens' 1659 sketches (see above) suggest he intended toanimate

Animation is a method by which still figures are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today, most anim ...

the skeleton to have it take off its head and place it back on its neck. This can be seen as an indication that the very first magic lantern demonstrations may already have included projections of simple animations.

In 1668, Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

wrote about the effects of a type of magic lantern installation: "Spectators not well versed in optics, that should see the various apparitions and disappearances, the motions, changes and actions that may this way be represented, would readily believe them to be supernatural and miraculous."

In 1675, German polymath and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ...

proposed a kind of world exhibition that would show all types of new inventions and spectacles. In a handwritten document he supposed it should open and close with magic lantern shows, including subjects "which can be dismembered, to represent quite extraordinary and grotesque movements, which men would not be capable of making" (translated from French).

Several reports of early magic lantern screenings possibly described moving pictures, but are not clear enough to conclude whether the viewers saw animated slides or motion depicted in still images.

In 1698, German engraver and publisher Johann Christoph Weigel described several lantern slides with mechanisms that made glass parts move over one fixed glass slide, for instance by the means of a silk thread, or grooves in which the mobile part slides.

By 1709 a German optician and glass grinder named Themme (or Temme) made moving lantern slides, including a carriage with rotating wheels, a cupid with a spinning wheel, a shooting gun, and falling bombs. Wheels were cut from the glass plate with a diamond and rotated by a thread that was spun around small brass wheels attached to the glass wheels. A paper slip mask would be quickly pulled away to reveal the red fiery discharge and the bullet from a shooting gun. Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach visited Themme's shop and liked the effects, but was disappointed about the very simple mechanisms. Nonetheless he bought seven moving slides, as well as twelve slides with four pictures each, which he thought were delicately painted.

Several types of mechanical slides were described and illustrated in Dutch professor of mathematics, physics, philosophy, medicine, and astronomy Pieter van Musschenbroek's second edition (1739) of ''Beginsels Der Natuurkunde'' (see illustration below). Pieter was the brother of Jan van Musschenbroek, the maker of an outstanding magic lantern with excellent lenses and a diaphragm (see illustration above).

In 1770, Edmé-Gilles Guyot described a method of using two slides for the depiction of a storm at sea, with waves on one slide and ships and a few clouds on another. Lanternists could project the illusion of mild waves turning into a wild sea tossing the ships around by increasing the movement of the separate slides. Guyot also detailed how projection on smoke could be used to create the illusion of ghosts hovering in the air, which would become a technique commonly used in phantasmagoria.

An especially intricate multiple rackwork mechanism was developed to show the movements of the planets (sometimes accompanied by revolving satellites) revolving around the sun. In 1795, one M. Dicas offered an early magic lantern system, the Lucernal or Portable Eidouranian, that showed the orbiting planets. From around the 1820s mechanical astronomical slides became quite common.The Magic Lantern Society. ''Encyclopedia of the Magic Lantern''. p. 21-22

Various types of mechanical slides

Various types of mechanisms were commonly used to add movement to the projected image:

*slipping slides: a movable glass plate with one or more figures (or any part of a picture for which movement was desired) was slipped over a stationary one, directly by hand or with a small drawbar (see: Fig. 7 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a tightrope walker sliding across the rope). A common example showed a creature that could move the pupils in its eyes, as if looking in all directions. A long piece of glass could show a procession of figures, or a train with several wagons. Quite convincing illusions of moving waves on a sea or lake have also been achieved with this method.

*slipping slides with masking: black paint on portions of the moving plate would mask parts of the underlying image — with a black background — on the stationary glass. This made it possible to hide and then reveal the previous position of a part, for instance a limb, to suggest repetitious movement. The suggested movement would be rather jerky and usually operated quickly. Masking in slides was also often used to create change rather than movement (see: Fig. 6 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a man, his wig and his hat): for instance a person's head could be replaced with that of an animal. More gradual and natural movement was also possible; for instance to make a nose grow very long by slowly moving a masking glass.

*lever slides: the moving part was operated by a lever. These could show a more natural movement than slipping slides and were mostly used for repetitive movements, for instance a woodcutter raising and lowering his axe, or a girl on a swing. (see: Fig. 5 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a drinking man raising and lowering his glass + Fig. 8: a lady curtsying)

*pulley slides: a pulley rotates the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill (see: fig. 4 on illustration by Van Musschenbroek)

*rack and pinion slides: turning the handle of a rackwork would rotate or lift the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill or for having a hot air balloon take off and descend. A more complex astronomical rackwork slide showed the planets and their satellites orbiting around the sun.

*fantoccini slides: jointed figures set in motion by levers, thin rods, or cams and worm wheels. A popular version had a somersaulting monkey with arms attached to mechanism that made it tumble with dangling feet. Named after the Italian word for animated puppets, like marionettes or jumping jacks. Two different British patents for slides with moving jointed figures were granted in 1891.

*a snow effect slide can add snow to another slide (preferably of a winter scene) by moving a flexible loop of material pierced with tiny holes in front of one of the lenses of a double or triple lantern.

Mechanical slides with abstract special effects include:

Various types of mechanisms were commonly used to add movement to the projected image:

*slipping slides: a movable glass plate with one or more figures (or any part of a picture for which movement was desired) was slipped over a stationary one, directly by hand or with a small drawbar (see: Fig. 7 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a tightrope walker sliding across the rope). A common example showed a creature that could move the pupils in its eyes, as if looking in all directions. A long piece of glass could show a procession of figures, or a train with several wagons. Quite convincing illusions of moving waves on a sea or lake have also been achieved with this method.

*slipping slides with masking: black paint on portions of the moving plate would mask parts of the underlying image — with a black background — on the stationary glass. This made it possible to hide and then reveal the previous position of a part, for instance a limb, to suggest repetitious movement. The suggested movement would be rather jerky and usually operated quickly. Masking in slides was also often used to create change rather than movement (see: Fig. 6 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a man, his wig and his hat): for instance a person's head could be replaced with that of an animal. More gradual and natural movement was also possible; for instance to make a nose grow very long by slowly moving a masking glass.

*lever slides: the moving part was operated by a lever. These could show a more natural movement than slipping slides and were mostly used for repetitive movements, for instance a woodcutter raising and lowering his axe, or a girl on a swing. (see: Fig. 5 on the illustration by Petrus van Musschenbroek: a drinking man raising and lowering his glass + Fig. 8: a lady curtsying)

*pulley slides: a pulley rotates the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill (see: fig. 4 on illustration by Van Musschenbroek)

*rack and pinion slides: turning the handle of a rackwork would rotate or lift the moving part and could for instance be used to turn the sails on a windmill or for having a hot air balloon take off and descend. A more complex astronomical rackwork slide showed the planets and their satellites orbiting around the sun.

*fantoccini slides: jointed figures set in motion by levers, thin rods, or cams and worm wheels. A popular version had a somersaulting monkey with arms attached to mechanism that made it tumble with dangling feet. Named after the Italian word for animated puppets, like marionettes or jumping jacks. Two different British patents for slides with moving jointed figures were granted in 1891.

*a snow effect slide can add snow to another slide (preferably of a winter scene) by moving a flexible loop of material pierced with tiny holes in front of one of the lenses of a double or triple lantern.

Mechanical slides with abstract special effects include:

*the Chromatrope: a slide that produces dazzling colorful geometrical patterns by rotating two painted glass discs in opposite directions, originally with a double pulley mechanism but later usually with a rackwork mechanism. It was possibly invented around 1844 by English glass painter and showman Henry Langdon Childe and soon added as a novelty to the program of the Royal Polytechnic Institution.

*the Astrometeoroscope or Astrometroscope: a large slide that projected a lacework of dots forming constantly changing geometrical line patterns, compared with stars and meteors. It was invented in or before 1858 by the Hungarian engineer S. Pilcher and used a very ingenious mechanism with two metal plates obliquely crossed with slits that moved to and fro in contrary directions. Except for when the only known example was used in a performance, it was kept locked away at the Polytechnic so no one could discover the secret technique. When the Polytechnic auctioned the device, Picher eventually paid an extravagant price for his own invention to keep its workings secret.

*the Eidotrope: counter-rotating discs of perforated metal or card (or wire gauze or lace), producing swirling Moiré patterns of bright white dots. It was invented by English scientist Charles Wheatstone in 1866.

*the Kaleidotrope: a slide with a single perforated metal or cardboard disc suspended on a spiral spring. The holes can be tinted with colored pieces of gelatin. When struck the disc's vibration and rotation sends the colored dots of light swirling around in all sorts of shapes and patterns. The device was demonstrated at the Royal Polytechnic Institution around 1870 and dubbed "Kaleidotrope" when commercial versions were marketed.

*the Cycloidotrope (circa 1865): a slide with an adjustable stylus bar for drawing geometric patterns on sooty glass when hand cranked during projection. The patterns are similar to that produced with a Spirograph.

*a Newton colour wheel slide that, when spinning fast enough, blends seven colours into a white circle

*the Chromatrope: a slide that produces dazzling colorful geometrical patterns by rotating two painted glass discs in opposite directions, originally with a double pulley mechanism but later usually with a rackwork mechanism. It was possibly invented around 1844 by English glass painter and showman Henry Langdon Childe and soon added as a novelty to the program of the Royal Polytechnic Institution.

*the Astrometeoroscope or Astrometroscope: a large slide that projected a lacework of dots forming constantly changing geometrical line patterns, compared with stars and meteors. It was invented in or before 1858 by the Hungarian engineer S. Pilcher and used a very ingenious mechanism with two metal plates obliquely crossed with slits that moved to and fro in contrary directions. Except for when the only known example was used in a performance, it was kept locked away at the Polytechnic so no one could discover the secret technique. When the Polytechnic auctioned the device, Picher eventually paid an extravagant price for his own invention to keep its workings secret.

*the Eidotrope: counter-rotating discs of perforated metal or card (or wire gauze or lace), producing swirling Moiré patterns of bright white dots. It was invented by English scientist Charles Wheatstone in 1866.

*the Kaleidotrope: a slide with a single perforated metal or cardboard disc suspended on a spiral spring. The holes can be tinted with colored pieces of gelatin. When struck the disc's vibration and rotation sends the colored dots of light swirling around in all sorts of shapes and patterns. The device was demonstrated at the Royal Polytechnic Institution around 1870 and dubbed "Kaleidotrope" when commercial versions were marketed.

*the Cycloidotrope (circa 1865): a slide with an adjustable stylus bar for drawing geometric patterns on sooty glass when hand cranked during projection. The patterns are similar to that produced with a Spirograph.

*a Newton colour wheel slide that, when spinning fast enough, blends seven colours into a white circle

Dissolving views

The effect of a gradual transition from one image to another, known as a dissolve in modern filmmaking, became the basis of a popular type of magic lantern show in England in the 19th century. Typical dissolving views showed landscapes dissolving from day to night or from summer to winter. This was achieved by aligning the projection of two matching images and slowly diminishing the first image while introducing the second image. The subject and the effect of magic lantern dissolving views is similar to the popular

The effect of a gradual transition from one image to another, known as a dissolve in modern filmmaking, became the basis of a popular type of magic lantern show in England in the 19th century. Typical dissolving views showed landscapes dissolving from day to night or from summer to winter. This was achieved by aligning the projection of two matching images and slowly diminishing the first image while introducing the second image. The subject and the effect of magic lantern dissolving views is similar to the popular Diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

theatre paintings that originated in Paris in 1822. 19th century magic lantern broadsides often used the terms ''dissolving view'', ''dioramic view'', or simply ''diorama'' interchangeably.

The effect was reportedly invented by phantasmagoria pioneer Paul de Philipsthal while in Ireland in 1803 or 1804. He thought of using two lanterns to make the spirit of Samuel appear out of a mist in his representation of the Witch of Endor

The Witch of Endor ( he, ''baʿălaṯ-ʾōḇ bəʿĒyn Dōr'', "she who owns the ''ʾōḇ'' of Endor") is a woman who, according to the Hebrew Bible, was consulted by Saul to summon the spirit of the prophet Samuel. Saul wished to receive ad ...

. While working out the desired effect, he got the idea of using the technique with landscapes. An 1812 newspaper about a London performance indicates that De Philipsthal presented what was possibly a relatively early incarnation of a dissolving views show, describing it as "a series of landscapes (in imitation of moonlight), which insensibly change to various scenes producing a very magical effect."

Another possible inventor is Henry Langdon Childe, who purportedly once worked for De Philipsthal. He is said to have invented the dissolving views in 1807, and to have improved and completed the technique in 1818. The oldest known use of the term "dissolving views" occurs on playbills for Childe's shows at the Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receivin ...

in London in 1837. Childe further popularized the dissolving views at the Royal Polytechnic Institution in the early 1840s.

Despite later reports about the early invention, and apart from De Philipsthal's 1812 performance, no reports of dissolving view shows before the 1820s are known. Some cases may involve confusion with the Diorama or similar media. In 1826, Scottish magician and ventriloquist M. Henry introduced what he described as "beautiful dissolvent scenes," "imperceptibly changing views," "dissolvent views," and "Magic Views"—created "by Machinery invented by M. Henry." In 1827, Henry Langdon Childe presented "Scenic Views, showing the various effects of light and shade," with a series of subjects that became classics for the dissolving views. In December 1827, De Philipsthal returned with a show that included "various splendid views (...) transforming themselves imperceptibly (as if it were by Magic) from one form into another."

Biunial lanterns, with two projecting optical sets in one apparatus, were produced to more easily project dissolving views. Possibly the first horizontal biunial lantern, dubbed the "Biscenascope" was made by the optician Mr. Clarke and presented at the Royal Adelaide Gallery in London on 5 December 1840. The earliest known illustration of a vertical biunial lantern, probably provided by E.G. Wood, appeared in the Horne & Thornthwaite catalogue in 1857. Later on triple lanterns enabled additional effects, for instance the effect of snow falling while a green landscape dissolves into a snowy winter version.

A mechanical device could be fitted on the magic lantern, which locked up a diaphragm on the first slide slowly whilst a diaphragm on a second slide opened simultaneously.

Philip Carpenter's copper-plate printing process, introduced in 1823, may have made it much easier to create duplicate slides with printed outlines that could then be colored differently to create dissolving view slides. However, all early dissolving view slides seem to have been hand-painted.

Experiments