liberation of Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The final battle of the

The final battle of the

Liberation of Nazi concentration camps and refugees: Allied forces began to discover the scale of

Liberation of Nazi concentration camps and refugees: Allied forces began to discover the scale of

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Four days later troops from the American 42nd Infantry Division found

Hitler dies by suicide: On 30 April 1945, as the Battle of Nuremberg and the Battle of Hamburg ended with American and British occupation, in addition to the

Hitler dies by suicide: On 30 April 1945, as the Battle of Nuremberg and the Battle of Hamburg ended with American and British occupation, in addition to the

Field Marshal Keitel's surrender

' BBC additional comment b

Peter – WW2 Site Helper

/ref> German forces in Bavaria surrender: At 14:30 on 5 May 1945, General Channel Islanders were informed about the German surrender after: At 10:00 on 8 May, the

Channel Islanders were informed about the German surrender after: At 10:00 on 8 May, the

RAF Site Diary 7/8 May

At 02:41 on the morning of 7 May, at SHAEF headquarters in Reims, France, the chief-of-staff of the German Armed Forces High Command, General Alfred Jodl, signed an unconditional surrender document for all German forces to the Allies. General

The

The

"Spreading Hesitation"

''Time''. 7 February 1955.

"The full authority of a sovereign state" was granted to the Federal Republic of Germany on 5 May 1955 under the terms of the Bonn–Paris conventions.

The treaty ended the military occupation of West German territory, but the three occupying powers retained some special rights, e.g. vis-à-vis

Deutsche Welle special coverage of the end of World War II

��features a global perspective.

On this Day 7 May 1945: Germany signs unconditional surrender

Account of German surrender

BBC * Charles Kiley ( Stars and Stripes Staff Writer

Details of the Surrender Negotiations ''This Is How Germany Gave Up''

* ttp://english.pobediteli.ru/ Multimedia map of the war(1024x768 & Macromedia Flash Plugin 7.x)

The final battle of the

The final battle of the European Theatre of World War II

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with t ...

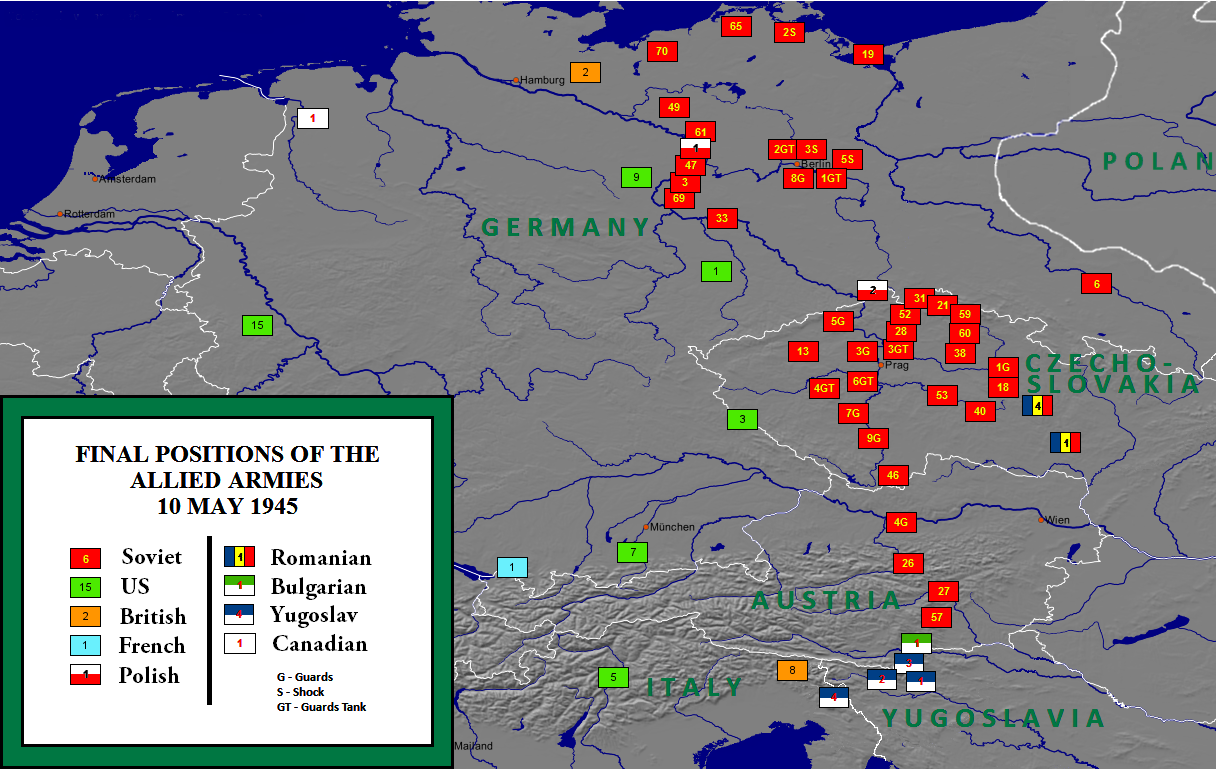

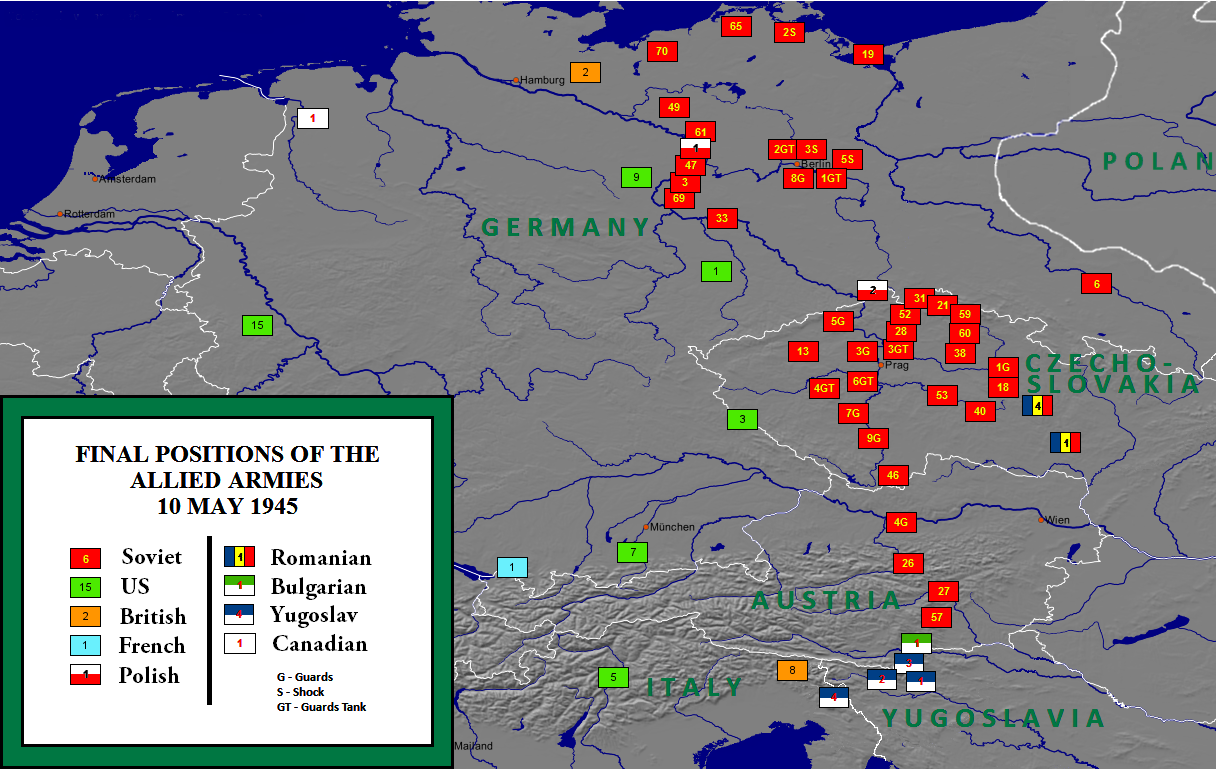

continued after the definitive overall surrender of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

to the Allies, signed by Field marshal Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal who held office as chief of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces, durin ...

on 8 May 1945 in Karlshorst

Karlshorst (, ; ; literally meaning ''Karl's nest'') is a locality in the borough of Lichtenberg in Berlin. Located there are a harness racing track and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (''HTW''), the largest University of Applie ...

, Berlin. After German dictator Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

and handing over of power to German Admiral Karl Dönitz in May of 1945, the Soviet troops conquered Berlin and accepted German surrender led by Dönitz. The last battles were fought as part of the Eastern Front which ended in the total surrender of all of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

’s remaining armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

and the German surrender officially ended World War II in Europe, such as in the Courland Pocket

The Courland Pocket (Blockade of the Courland army group), (german: Kurland-Kessel)/german: Kurland-Brückenkopf (Courland Bridgehead), lv, Kurzemes katls (Courland Cauldron) or ''Kurzemes cietoksnis'' (Courland Fortress)., group=lower-alpha ...

from Army Group North

Army Group North (german: Heeresgruppe Nord) was a German strategic formation, commanding a grouping of field armies during World War II. The German Army Group was subordinated to the ''Oberkommando des Heeres'' (OKH), the German army high comm ...

in the Baltics

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

lasting until 10 May 1945 and in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

during the Prague offensive

The Prague offensive (russian: Пражская стратегическая наступательная операция, Prazhskaya strategicheskaya nastupatel'naya operatsiya, lit=Prague strategic offensive) was the last major military ...

on 11 May 1945.

Final events before the end of the war in Europe

Red Army soldiers from the 322nd Rifle Division liberatedAuschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It ...

on 27 January 1945 at 15:00. Two hundred and thirty-one Red Army soldiers died in the fighting around Monowitz concentration camp

Monowitz (also known as Monowitz-Buna, Buna and Auschwitz III) was a Nazi concentration camp and labor camp (''Arbeitslager'') run by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland from 1942–1945, during World War II and the Holocaust. For most of its existe ...

, Birkenau, and Auschwitz I, as well as the towns of Oświęcim and Brzezinka. For most of the survivors, there was no definite moment of liberation. After the death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

away from the camp, the ''SS-Totenkopfverbände

''SS-Totenkopfverbände'' (SS-TV; ) was the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organization responsible for administering the Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps for Nazi Germany, among similar duties. While the '' Totenkopf'' was the unive ...

'' guards had left.

About 7,000 prisoners had been left behind, most of whom were seriously ill due to the effects of their imprisonment. Most of those left behind were middle-aged adults or children younger than 15. Red Army soldiers found 600 corpses, 370,000 men's suits, 837,000 articles of women's clothing, and seven tonnes (7.7 tons) of human hair. At Monowitz camp, there were about 800 survivors and the camp was liberated on 27 January by the Soviet 60th Army, part of the 1st Ukrainian Front.

Soldiers who were used to death were shocked by the Nazis' treatment of prisoners. Red Army general Vasily Petrenko, commander of the 107th Infantry Division, remarked, "I, who saw people dying every day, was shocked by the Nazis' indescribable hatred toward the inmates who had turned into living skeletons. I read about the Nazis' treatment of prisoners in various leaflets, but there was nothing about the Nazis' treatment of women, children, and old men. It was in Auschwitz that I found out about the fate of the Jews."

As soon as they arrived, the liberating forces, which contained the Polish Red Cross

Polish Red Cross ( pl, Polski Czerwony Krzyż, abbr. PCK) is the Polish member of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Its 19th-century roots may be found in the Russian and Austrian Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwe ...

, helped survivors by organizing medical care and food; Red Army hospitals cared for 4,500 survivors. There were also efforts to document the camp. As late as June 1945, there were still 300 survivors at the camp who were too weak to be moved.

Allied forces begin to take large numbers of Axis prisoners: The total number of prisoners taken on the Western Front in April 1945 by the Western Allies was 1,500,000. April also witnessed the capture of at least 120,000 German troops by the Western Allies in the last campaign of the war in Italy.''The Times'', 1 May 1945, page 4 In the three to four months up to the end of April, over 800,000 German soldiers surrendered on the Eastern Front. In early April, the first Allied-governed ''Rheinwiesenlager

The ''Rheinwiesenlager'' (, ''Rhine meadow camps'') were a group of 19 camps built in the Allied-occupied part of Germany by the U.S. Army to hold captured German soldiers at the close of the Second World War. Officially named Prisoner of Wa ...

s'' were established in western Germany to hold hundreds of thousands of captured or surrendered Axis Forces

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were N ...

personnel. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allied forces in north west Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander in SHAEF t ...

(SHAEF) reclassified all prisoners as Disarmed Enemy Forces

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF, less commonly, Surrendered Enemy Forces) was a US designation for soldiers who surrendered to an adversary after hostilities ended, and for those POWs who had already surrendered and were held in camps in occupied Ge ...

, not POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

s (prisoners of war). The legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts, which is then used in order to help reach a decision or to apply a legal rule. The concept is used almost exclusively in common law jurisdictions, particularly in England and Wales.

Devel ...

circumvented provisions under the Geneva Convention of 1929 on the treatment of former combatants. By October, thousands had died in the camps from starvation, exposure and disease.

Liberation of Nazi concentration camps and refugees: Allied forces began to discover the scale of

Liberation of Nazi concentration camps and refugees: Allied forces began to discover the scale of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, confirming the findings of Pilecki's 1943 Report. The advance into Germany uncovered numerous Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as conce ...

and forced labour facilities. Up to 60,000 prisoners were at Bergen-Belsen when it was liberated on 15 April 1945, by the British 11th Armoured Division

The 11th Armoured Division was an armoured division of the British Army which was created in March 1941 during the Second World War. The division was formed in response to the unanticipated success of the German panzer divisions. The 11th Armo ...

."The 11th Armoured Division (Great Britain)"United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Four days later troops from the American 42nd Infantry Division found

Dachau

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

. Allied troops forced the remaining SS guards to gather up the corpses and place them in mass graves. Due to the prisoners' poor physical condition, thousands continued to die after liberation. Captured SS guards were subsequently tried at Allied war crime tribunals where many were sentenced to death. Some Nazi guards and personnel were murdered outright upon the discovery of their crimes. However, up to 10,000 Nazi war criminals eventually fled Europe using ratlines

Ratlines () are lengths of thin line tied between the shrouds of a sailing ship to form a ladder. Found on all square-rigged ships, whose crews must go aloft to stow the square sails, they also appear on larger fore-and-aft rigged vessels to ...

such as ODESSA

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

.

German forces withdraw from Finland: On 25 April 1945, the last German troops withdrew from Finnish Lapland and made their way into occupied Norway. On 27 April 1945, the '' Raising the Flag on the Three-Country Cairn'' photograph was taken.

Mussolini is executed: On 25 April 1945, Italian partisans

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

liberated Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

and Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. Th ...

. On 27 April 1945, as Allied forces closed in on Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 19 ...

was captured by Italian partisans. It is disputed whether he was trying to flee from Italy to Switzerland (through the Splügen Pass

The Splügen Pass (german: Splügenpass; it, Passo dello Spluga; rm, Pass dal Spleia ) is an Alpine mountain pass of the Lepontine Alps. It connects the Swiss, Grisonian Splügen to the north below the pass with the Italian Chiavenna to the s ...

), and was travelling with a German anti-aircraft battalion. On 28 April, Mussolini was executed in Giulino (a civil parish of Mezzegra

Mezzegra is a former ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Como in the Italian region Lombardy. Since 21 January 2014 it is part of the comune of Tremezzina.

Geography

It lies on the northwestern shore of Lake Como between Tremezzo and Le ...

); the other fascists captured with him were taken to Dongo and executed there. The bodies were then taken to Milan and hung up on the Piazzale Loreto of the city. On 29 April, Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's ''Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during ...

surrendered all Fascist Italian armed forces at Caserta. This included Army Group Liguria Army Liguria (''Armee Ligurien'', or LXXXXVII Army) was an army formed for the National Republican Army (''Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano'', or ENR). The ENR was the national army of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's Italian Social Republic (''R ...

. Graziani was the Minister of Defence for Mussolini's Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

.

Hitler dies by suicide: On 30 April 1945, as the Battle of Nuremberg and the Battle of Hamburg ended with American and British occupation, in addition to the

Hitler dies by suicide: On 30 April 1945, as the Battle of Nuremberg and the Battle of Hamburg ended with American and British occupation, in addition to the Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula–O ...

raging above him with the Soviets surrounding the city, along with his escape route cut off by the Americans, realizing that all was lost and not wishing to suffer Mussolini's fate, German dictator Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

died by suicide in his ''Führerbunker

The ''Führerbunker'' () was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters ...

'' along with Eva Braun

Eva Anna Paula Hitler (; 6 February 1912 – 30 April 1945) was a German photographer who was the longtime companion and briefly the wife of Adolf Hitler. Braun met Hitler in Munich when she was a 17-year-old assistant and model for his ...

, his long-term partner whom he had married less than 40 hours earlier. In his will, Hitler dismissed ''Reichsmarschall

(german: Reichsmarschall des Großdeutschen Reiches; ) was a rank and the highest military office in the ''Wehrmacht'' specially created for Hermann Göring during World War II. It was senior to the rank of , which was previously the highes ...

'' Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, his second-in-command and Interior minister

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

after each of them separately tried to seize control of the crumbling remains of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Hitler appointed his successors as follows; ''Großadmiral'' Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government foll ...

as the new '' Reichspräsident'' ("President of Germany") and Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 194 ...

as the new ''Reichskanzler

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

'' (Chancellor of Germany). However, Goebbels died by suicide the next day, leaving Dönitz as the sole leader of Germany.

German forces in Italy surrender: On 29 April, the day before Hitler died, Oberstleutnant Schweinitz and Sturmbannführer Wenner, plenipotentiaries for Generaloberst Heinrich von Vietinghoff

Heinrich Gottfried Otto Richard von Vietinghoff genannt Scheel (6 December 1887 – 23 February 1952) was a German general (''Generaloberst'') of the Wehrmacht during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oa ...

and SS Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff

Karl Friedrich Otto Wolff (13 May 1900 – 17 July 1984) was a German SS functionary who served as Chief of Personal Staff Reichsführer-SS (Heinrich Himmler) and an SS liaison to Adolf Hitler during World War II. He ended the war as the Supr ...

, signed a surrender document at Caserta

Caserta () is the capital of the province of Caserta in the Campania region of Italy. It is an important agricultural, commercial, and industrial ''comune'' and city. Caserta is located on the edge of the Campanian plain at the foot of the Camp ...

after prolonged unauthorised secret negotiations with the Western Allies, which were viewed with great suspicion by the Soviet Union as trying to reach a separate peace. In the document, the Germans agreed to a ceasefire and surrender of all the forces under the command of Vietinghoff on 2 May at 2 pm. Accordingly, after some bitter wrangling between Wolff and Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring (30 November 1885 – 16 July 1960) was a German ''Generalfeldmarschall'' of the Luftwaffe during World War II who was subsequently convicted of war crimes. In a military career that spanned both world wars, Kesselring bec ...

in the early hours of 2 May, nearly 1,000,000 men in Italy and Austria surrendered unconditionally to British Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander on 2 May at 2 pm.

German forces in Berlin surrender: The Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula–O ...

ended on 2 May. On that date, ''General der Artillerie'' Helmuth Weidling

Helmuth Otto Ludwig Weidling (2 November 1891 – 17 November 1955) was a German general during World War II. He was the last commander of the Berlin Defence Area during the Battle of Berlin, and led the defence of the city against Soviet fo ...

, the commander of the Berlin Defense Area, unconditionally surrendered the city to General Vasily Chuikov

Vasily Ivanovich Chuikov (russian: link=no, Васи́лий Ива́нович Чуйко́в; ; – 18 March 1982) was a Soviet Union, Soviet military commander and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He is best known for commanding the 62nd Arm ...

of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

. On the same day the officers commanding the two armies of Army Group Vistula north of Berlin, (General Kurt von Tippelskirch

__NOTOC__

Kurt Oskar Heinrich Ludwig Wilhelm von Tippelskirch (9 October 1891 – 10 May 1957) was a general in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II who commanded several armies and Army Group Vistula. He surrendered to the Unite ...

, commander of the German 21st Army and General Hasso von Manteuffel

Freiherr Hasso Eccard von Manteuffel (14 January 1897 – 24 September 1978) was a German baron born to the Prussian noble von Manteuffel family and was a general during World War II who commanded the 5th Panzer Army. He was a recipient of the ...

, commander of Third Panzer Army), surrendered to the Western Allies. 2 May is also believed to have been the day when Hitler's deputy Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

died, from the account of Artur Axmann

Artur Axmann (18 February 1913 – 24 October 1996) was the German Nazi national leader ('' Reichsjugendführer'') of the Hitler Youth (''Hitlerjugend'') from 1940 to 1945, when the war ended. He was the last living Nazi with a rank equivalent ...

who saw Bormann's corpse in Berlin near the Lehrter Bahnhof

Berlin Hauptbahnhof () (English: Berlin Central Station) is the main railway station in Berlin, Germany. It came into full operation two days after a ceremonial opening on 26 May 2006. It is located on the site of the historic Lehrter Bahnhof, ...

railway station after encountering a Soviet Red Army patrol. Lehrter Bahnhof is close to where the remains of Bormann, confirmed as his by a DNA test in 1998, were unearthed on 7 December 1972.

German forces in North West Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands surrender: On 4 May 1945, the British Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered a ...

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and th ...

took the unconditional military surrender at Lüneburg from ''Generaladmiral'' Hans-Georg von Friedeburg

Hans-Georg von Friedeburg (15 July 1895 – 23 May 1945) was a German admiral, the deputy commander of the U-boat Forces of Nazi Germany and the second-to-last Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine. He was the only representative of the armed ...

, and General Eberhard Kinzel

__NOTOC__

Eberhard Kinzel (18 October 1897 – 25 June 1945) was a general in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II who commanded several divisions. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Military career

Kinzel ...

, of all German forces "in Holland ic in northwest Germany including the Frisian Islands and Heligoland and all other islands, in Schleswig-Holstein, and in Denmark… includ ngall naval ships in these areas", at the Timeloberg on Lüneburg Heath

Lüneburg Heath (german: Lüneburger Heide) is a large area of heath, geest, and woodland in the northeastern part of the state of Lower Saxony in northern Germany. It forms part of the hinterland for the cities of Hamburg, Hanover and Brem ...

; an area between the cities of Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German States of Germany, state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germa ...

and Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state con ...

. The number of German land, sea and air forces involved in this surrender amounted to 1,000,000 men.

On 5 May, ''Großadmiral'' Dönitz ordered all U-boats to cease offensive operations and return to their bases.

At 16:00 on 5 May, German '' Oberbefehlshaber Niederlande'' supreme commander ''Generaloberst

A ("colonel general") was the second-highest general officer rank in the German ''Reichswehr'' and ''Wehrmacht'', the Austro-Hungarian Common Army, the East German National People's Army and in their respective police services. The rank was ...

'' Johannes Blaskowitz

Johannes Albrecht Blaskowitz (10 July 1883 – 5 February 1948) was a German ''Generaloberst'' during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. After joining the Imperial German Army in 1 ...

surrendered to I Canadian Corps

I Canadian Corps was one of the two corps fielded by the Canadian Army during the Second World War.

History

From December 24, 1940, until the formation of the First Canadian Army in April 1942, there was a single unnumbered Canadian Corps. I Ca ...

commander Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Charles Foulkes in the Dutch town of Wageningen

Wageningen () is a municipality and a historic city in the central Netherlands, in the province of Gelderland. It is famous for Wageningen University, which specialises in life sciences. The municipality had a population of in , of which many t ...

, in the presence of Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

(acting as commander-in-chief of the Dutch Interior Forces).Ron Goldstein Field Marshal Keitel's surrender

' BBC additional comment b

Peter – WW2 Site Helper

/ref> German forces in Bavaria surrender: At 14:30 on 5 May 1945, General

Hermann Foertsch

Hermann Foertsch (4 April 1895 – 27 December 1961) was a German general during World War II who held commands at the divisional, corps and army levels. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany.

Foertsch was t ...

surrendered all forces between the Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohe ...

n mountains and the Upper Inn river to the American General Jacob L. Devers

Jacob Loucks Devers (; 8 September 1887 – 15 October 1979) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the 6th Army Group in the European Theater during World War II. He was involved in the development and adoption of numerous ...

, commander of the American 6th Army Group.

Central Europe: On 5 May 1945, the Czech resistance started the Prague uprising

The Prague uprising ( cs, Pražské povstání) was a partially successful attempt by the Czech resistance movement to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation in May 1945, during the end of World War II. The preceding six years of ...

. The following day, the Soviets launched the Prague Offensive

The Prague offensive (russian: Пражская стратегическая наступательная операция, Prazhskaya strategicheskaya nastupatel'naya operatsiya, lit=Prague strategic offensive) was the last major military ...

. In Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth l ...

, ''Gauleiter'' Martin Mutschmann

Martin Mutschmann (9 March 1879 – 14 February 1947) was the Nazi Regional Leader (''Gauleiter'') of the state of Saxony (''Gau Saxony'') during the time of the Third Reich.

Early years

Born in Hirschberg on the Saale in the Principality ...

let it be known that a large-scale German offensive on the Eastern Front was about to be launched. Within two days, Mutschmann abandoned the city but was captured by Soviet troops while trying to escape.

Hermann Göring's surrender: On 6 May, ''Reichsmarshall'' and Hitler's second-in-command, Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, surrendered to General Carl Spaatz

Carl Andrew Spaatz (born Spatz; June 28, 1891 – July 14, 1974), nicknamed "Tooey", was an American World War II general. As commander of Strategic Air Forces in Europe in 1944, he successfully pressed for the bombing of the enemy's oil produc ...

, who was the commander of the operational United States Air Forces in Europe

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

, along with his wife and daughter at the Germany-Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

border. He was by this time the most senior Nazi official still alive.

German forces in Breslau surrender: At 18:00 on 6 May, General Hermann Niehoff, the commandant of Breslau, a 'fortress' city surrounded and besieged for months, surrendered to the Soviets.

Jodl and Keitel surrender all German armed forces unconditionally: Thirty minutes after the fall of "''Festung Breslau

The siege of Breslau, also known as the Battle of Breslau, was a three-month-long siege of the city of Breslau in Lower Silesia, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland), lasting to the end of World War II in Europe. From 13 February 1945 to 6 May 194 ...

''" (''Fortress Breslau''), General Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German ''Generaloberst'' who served as the chief of the Operations Staff of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' – the German Armed Forces High Command – throughout World ...

arrived in Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

and, following Dönitz's instructions, offered to surrender all forces fighting the Western Allies. This was exactly the same negotiating position that von Friedeburg had initially made to Montgomery, and like Montgomery, the Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Com ...

, General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, threatened to break off all negotiations unless the Germans agreed to a complete unconditional surrender to all the Allies on all fronts. Eisenhower explicitly told Jodl that he would order western lines closed to German soldiers, thus forcing them to surrender to the Soviets. Jodl sent a signal to Dönitz, who was in Flensburg

Flensburg (; Danish, Low Saxon: ''Flensborg''; North Frisian: ''Flansborj''; South Jutlandic: ''Flensborre'') is an independent town (''kreisfreie Stadt'') in the north of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Flensburg is the centre of ...

, informing him of Eisenhower's declaration. Shortly after midnight, Dönitz, accepting the inevitable, sent a signal to Jodl authorizing the complete and total surrender of all German forces.

Channel Islanders were informed about the German surrender after: At 10:00 on 8 May, the

Channel Islanders were informed about the German surrender after: At 10:00 on 8 May, the Channel Island

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

ers were informed by the German authorities that the war was over. British prime minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

made a radio broadcast at 15:00 during which he announced: "Hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight tonight, but in the interests of saving lives the 'Cease fire' began yesterday to be sounded all along the front, and our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed today."During the summers of World War II, Britain was on British Double Summer Time which meant that the country was ahead of CET time by one hour. This means that the surrender time in the UK was "effective from 0001 hours on May 9RAF Site Diary 7/8 May

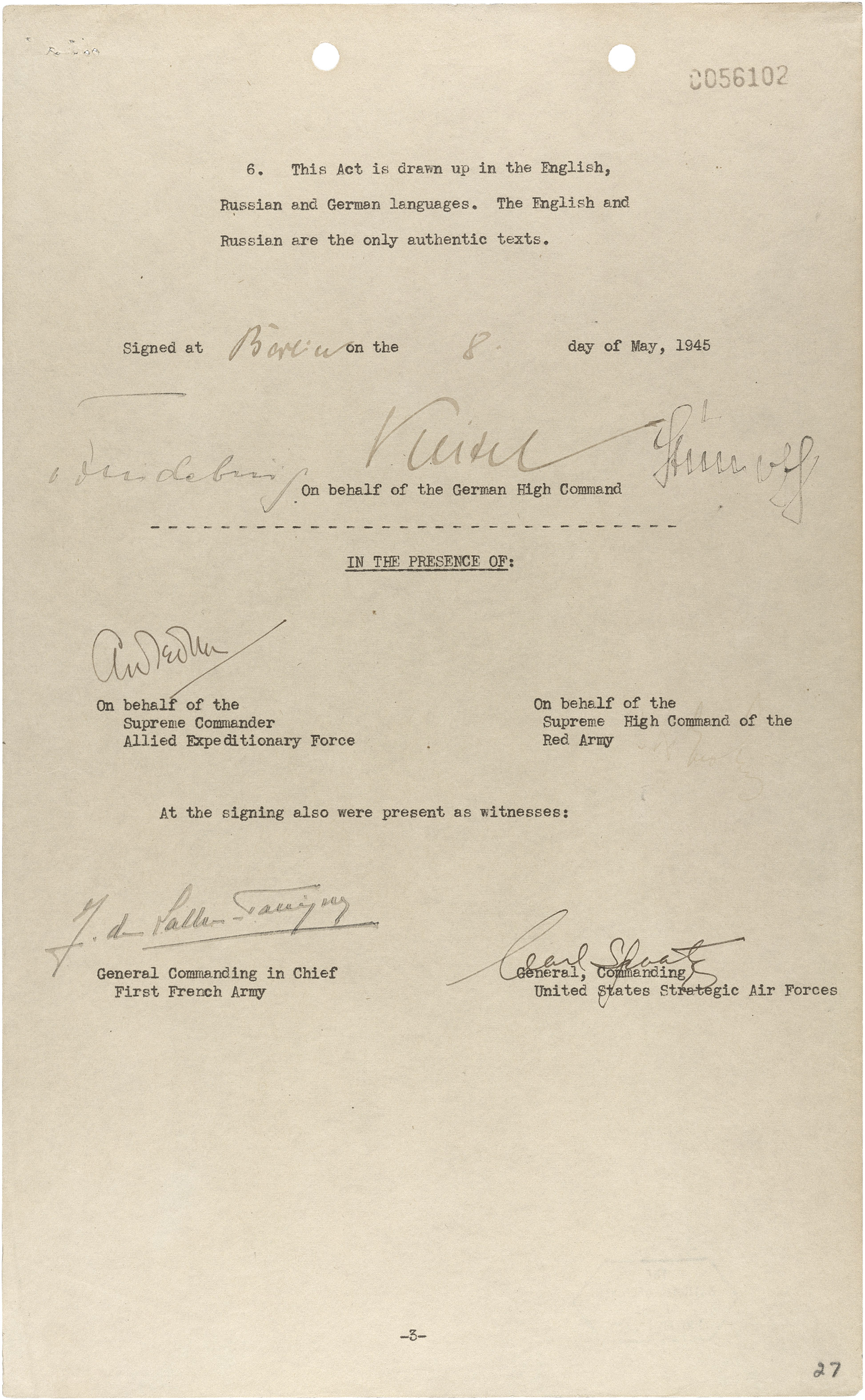

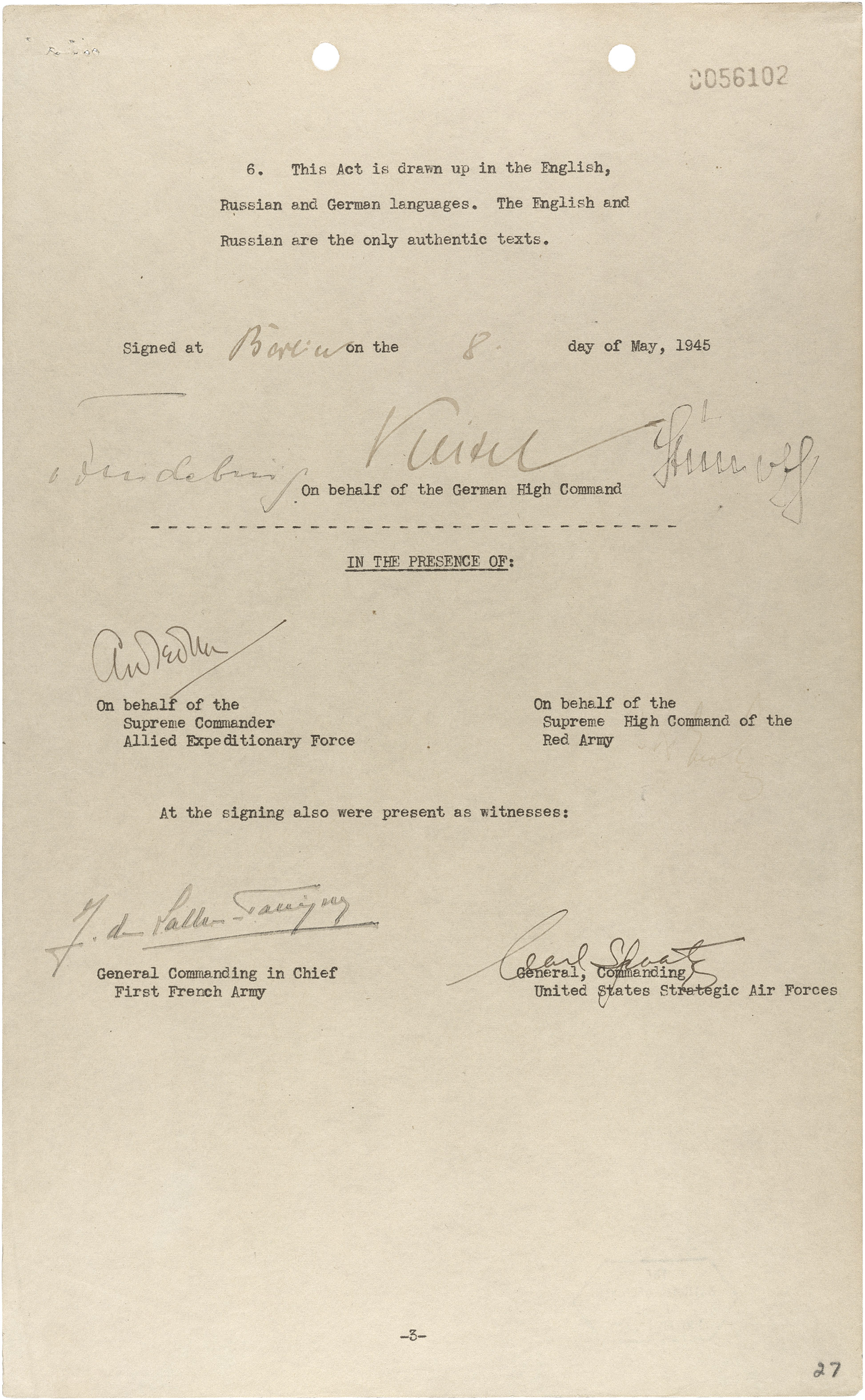

At 02:41 on the morning of 7 May, at SHAEF headquarters in Reims, France, the chief-of-staff of the German Armed Forces High Command, General Alfred Jodl, signed an unconditional surrender document for all German forces to the Allies. General

Franz Böhme

Franz Friedrich Böhme (15 April 1885 – 29 May 1947) was an Army officer who served in succession with the Austro-Hungarian Arny, the Austrian Army and the German Wehrmacht. He rose to the rank of general during World War II, serving as Co ...

announced the unconditional surrender of German troops in Norway on 7 May. It included the phrase "All forces under German control to cease active operations at 2301 hours Central European Time

Central European Time (CET) is a standard time which is 1 hour ahead of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

The time offset from UTC can be written as UTC+01:00.

It is used in most parts of Europe and in a few North African countries.

CET i ...

on May 8, 1945." The next day, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal who held office as chief of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces, durin ...

and other German OKW representatives travelled to Berlin, and shortly before midnight signed another document of unconditional surrender, again surrendering to all the Allied forces, this time in the presence of Marshal Georgi Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

and representatives of SHAEF

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allied forces in north west Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander in SHAEF t ...

. The signing ceremony took place in a former German Army Engineering School in the Berlin district of Karlshorst

Karlshorst (, ; ; literally meaning ''Karl's nest'') is a locality in the borough of Lichtenberg in Berlin. Located there are a harness racing track and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (''HTW''), the largest University of Applie ...

; it now houses the German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst

The Museum Berlin-Karlshorst, previously named ''German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst'' (Deutsch-Russisches Museum Berlin-Karlshorst) is dedicated to German-Soviet and German-Russian relations with a focus on the German-Soviet war of 1941–1 ...

.

Aftermath of the war

VE-Day: Following news of the German surrender, spontaneous celebrations erupted all over the world on 7 May, including in Western Europe and the United States. As the Germans officially set the end of operations for 2301Central European Time

Central European Time (CET) is a standard time which is 1 hour ahead of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

The time offset from UTC can be written as UTC+01:00.

It is used in most parts of Europe and in a few North African countries.

CET i ...

on 8 May, that day is celebrated across Europe as V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

. Most of the former Soviet Union celebrates Victory Day

Victory Day is a commonly used name for public holidays in various countries, where it commemorates a nation's triumph over a hostile force in a war or the liberation of a country from hostile occupation. In many cases, multiple countries may ob ...

on 9 May, as the end of operations occurred after midnight Moscow Time

Moscow Time (MSK, russian: моско́вское вре́мя) is the time zone for the city of Moscow, Russia, and most of western Russia, including Saint Petersburg. It is the second-westernmost of the eleven time zones of Russia. It has ...

.

German units cease fire: Although the military commanders of most German forces obeyed the order to surrender issued by the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW)—the German Armed Forces High Command—not all commanders did so. The largest contingent was Army Group Centre

Army Group Centre (german: Heeresgruppe Mitte) was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created on 22 June 1941, as one of three German Army fo ...

under the command of ''Generalfeldmarschall'' Ferdinand Schörner, who had been promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the Army on 30 April in Hitler's last will and testament. On 8 May, Schörner deserted his command and flew to Austria; the Soviet Army sent overwhelming force against Army Group Centre in the Prague Offensive

The Prague offensive (russian: Пражская стратегическая наступательная операция, Prazhskaya strategicheskaya nastupatel'naya operatsiya, lit=Prague strategic offensive) was the last major military ...

, forcing many of the German units in there to capitulate by 11 May. The other units of the Army Group which did not surrender on 8 May were forced to surrender.

* On, 9 May, the Second Army, under the command of General von Saucken, on the Heiligenbeil and Danzig beachheads, on the Hel Peninsula

Hel Peninsula (; pl, Mierzeja Helska, Półwysep Helski; csb, Hélskô Sztremlëzna; german: Halbinsel Hela or ''Putziger Nehrung'') is a sand bar peninsula in northern Poland separating the Bay of Puck from the open Baltic Sea. It is lo ...

in the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in t ...

delta surrendered; as did the forces on the Greek islands; and the garrisons of most of the last Atlantic pockets in France, in Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With ...

(after the Allied siege).

* The Atlantic Pocket of Lorient

Lorient (; ) is a town ('' commune'') and seaport in the Morbihan department of Brittany in western France.

History

Prehistory and classical antiquity

Beginning around 3000 BC, settlements in the area of Lorient are attested by the presen ...

surrendered on 10 May.

* The Atlantic Pocket of Saint-Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocea ...

surrendered on 11 May.

* The Battle of Slivice, the last battle in occupied Czechoslovakia, occurred on 12 May.

* On 13 May, the Red Army halted all offensives in Europe. Isolated pockets of resistance in Czechoslovakia were mopped up by this date.

* The garrison on Alderney

Alderney (; french: Aurigny ; Auregnais: ) is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands. It is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown dependency. It is long and wide.

The island's area is , making it the third-large ...

, one of the Channel Islands occupied by the Germans, surrendered on 16 May, one week after the garrisons on Guernsey

Guernsey (; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; french: Guernesey) is an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy that is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency.

It is the second largest of the Channel Islands, ...

and Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label=Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the la ...

had surrendered on 9 May and those on Sark

Sark (french: link=no, Sercq, ; Sercquiais: or ) is a part of the Channel Islands in the southwestern English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France. It is a royal fief, which forms part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, with its own set of l ...

on 10 May.

* A military engagement took place in Yugoslavia (today's Slovenia), on 14 and 15 May, known as the Battle of Poljana.

* The fighting during the Georgian uprising on Texel in the Netherlands lasted until 20 May.

* The last battle in Europe, the Battle of Odžak between the Yugoslav Army and the Croatian Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Croatia ( hr, Oružane snage Republike Hrvatske – OSRH) is the military service of Croatia.

The President is the Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief, and exercises administrative powers in times of war by giv ...

, concluded on 25 May. The remaining Croatian soldiers escaped to the forest.

* A small group of German soldiers, deployed on Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group rang ...

in Operation Haudegen

Operation Haudegen ( peration Broadsword was the name of a Nazi Germany, German operation during the Second World War to establish meteorological stations on Svalbard. In September 1944, the submarine ''U-307'' and the supply ship ''Carl J. ...

to establish and man a weather station there, lost radio contact in May 1945; they surrendered to some Norwegian seal hunters on 4 September, two days after Japan formally surrendered.

Debellation: At the time the Allied powers assumed that a debellation had occurred (the end of a war caused by the complete destruction of a hostile state), and their actions during the immediate post war period were based on that legal premise (however the German government's legal position during and after the reunification of Germany

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

is that the state remained in existence although moribund in the immediate post war period).

Dönitz government ordered dissolved by Eisenhower: Karl Dönitz continued to act as if he were the German head of state, but his Flensburg government (so called because it was based at Flensburg in northern Germany and controlled only a small area around the town), was not recognized by the Allies. On 12 May an Allied liaison team arrived in Flensburg and took quarters aboard the passenger ship ''Patria''. The liaison officers and the Supreme Allied Headquarters soon realized that they had no need to act through the Flensburg government and that its members should be arrested. On 23 May, acting on SHAEF's orders and with the approval of the Soviets, American Major General Rooks summoned Dönitz aboard the ''Patria'' and communicated to him that he and all the members of his Government were under arrest and that their government was dissolved. The Allies had a problem because they realized that although the German armed forces had surrendered unconditionally, SHAEF had failed to use the document created by the "European Advisory Commission The formation of the European Advisory Commission (EAC) was agreed on at the Moscow Conference on 30 October 1943 between the foreign ministers of the United Kingdom, Anthony Eden, the United States, Cordell Hull, and the Soviet Union, Vyachesl ...

" (EAC) and so there had been no formal surrender by the civilian German government. This was considered a very important issue, because just as the civilian, but not military, surrender in 1918 had been used by Hitler to create the "stab in the back

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an antisemitic conspiracy theory that was widely believed and promulgated in Germany after 1918. It maintained that the Imperial German Army did not lose World War I on the battlefield, but was instead b ...

" argument, the Allies did not want to give any future hostile German regime a legal argument to resurrect an old quarrel.

On 20 September 1945, the Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority (german: Alliierter Kontrollrat) and also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany and Allied-occupied Austria after the end of ...

passed its Control Council Law No. 1 - Repealing of Nazi Laws, which repealed numerous pieces of legislation enacted by the national-socialist regime, putting a ''de jure'' end to the Government of Nazi Germany

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gove ...

. Incidentally, this law should have theoretically reestablished the Weimar Constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich (german: Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (''Weimarer Verfassung''), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era (1919–1933). The c ...

, however this constitution stayed irrelevant on the grounds of the powers of the Allied Control Council acting as occupying forces. On 10 October 1945, Control Council Law No. 2 was also passed, formally abolishing all national socialist organisations.

Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany and the Assumption of Supreme Authority by Allied Powers was signed by the four Allies on 5 June. It included the following:

The

The Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

was signed on 1 August 1945. In connection with this, the leaders of the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union planned the new postwar German government, resettled war territory boundaries, ''de facto'' annexed a quarter of pre-war Germany situated east of the Oder-Neisse line, and mandated and organized the expulsion of the millions of Germans who remained in the annexed territories and elsewhere in the east. They also ordered German demilitarization

Demilitarisation or demilitarization may mean the reduction of state armed forces; it is the opposite of militarisation in many respects. For instance, the demilitarisation of Northern Ireland entailed the reduction of British security and military ...

, denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

, industrial disarmament and settlements of war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

. But, as France (at American insistence) had not been invited to the Potsdam Conference, so the French representatives on the Allied Control Council subsequently refused to recognise any obligation to implement the Potsdam Agreement; with the consequence that much of the programme envisaged at Potsdam, for the establishment of a German government and state adequate for accepting a peace settlement, remained a dead letter.

Operation Keelhaul

Operation Keelhaul was a forced repatriation of Russian civilians (non-Soviet citizens) and Soviet citizens to the Soviet Union. While forced repatriation focused on Soviet Armed Forces POWs of Germany and Russian Liberation Army members, it inclu ...

began the Allies' forced repatriation of displaced persons, families, anti-communists, White Russians, former Soviet Armed Forces

The Soviet Armed Forces, the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union and as the Red Army (, Вооружённые Силы Советского Союза), were the armed forces of the Russian SFSR (1917–1922), the Soviet Union (1922–1991), and th ...

POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

s, foreign slave workers, soldier volunteers and Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

, and Nazi collaborators to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Between 14 August 1946 and 9 May 1947, up to five million people were forcibly handed over to the Soviets. On return, most deportees faced imprisonment or execution; on some occasions the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

began killing people before Allied troops had departed from the rendezvous points.

The Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority (german: Alliierter Kontrollrat) and also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany and Allied-occupied Austria after the end of ...

was created to effect the Allies' assumed supreme authority over Germany, specifically to implement their assumed joint authority over Germany. On 30 August, the Control Council constituted itself and issued its first proclamation, which informed the German people of the council's existence and asserted that the commands and directives issued by the Commanders-in-Chief in their respective zones were not affected by the establishment of the council.

Cessation of formal hostilities and peace treaties

Cessation of hostilities between the United States and Germany was proclaimed on 13 December 1946 by US President Truman. The Paris Peace Conference ended on 10 February 1947 with the signing ofpeace treaties

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surren ...

by the wartime Allies with the former European Axis powers ( Italy, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

) and their co-belligerent ally Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

.

The Federal Republic of Germany, which had been founded on 23 May 1949 (when its Basic Law was promulgated), had its first government formed on 20 September 1949 while the German Democratic Republic was formed on 7 October.

End of state of war with Germany was declared by many former Western Allies from 1950. In the Petersberg Agreement

The Petersberg Agreement is an international treaty that extended the rights of the government of West Germany vis-a-vis the occupying forces of the United Kingdom, France, and the United States. It is viewed as the first major step of West Germa ...

of 22 November 1949, it was noted that the West German government wanted an end to the state of war, but the request could not be granted. The US state of war with Germany was being maintained for legal reasons, and though it was softened somewhat it was not suspended since "the US wants to retain a legal basis for keeping a US force in Western Germany".

At a meeting for the foreign ministers of France, the UK, and the US in New York from 12 September – 19 December 1950, it was stated that among other measures to strengthen West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

's position in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

that the western allies would "end by legislation the state of war with Germany". In 1951, many former Western Allies did end their state of war with Germany: Australia (9 July), Canada, Italy, New Zealand, the Netherlands (26 July), South Africa, the United Kingdom (9 July), and the United States (19 October). The state of war between Germany and the Soviet Union was ended in early 1955.''Time''. 7 February 1955.

West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under ...

.

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (german: Vertrag über die abschließende Regelung in Bezug auf Deutschland;

rus, Договор об окончательном урегулировании в отношении Ге� ...

was signed following the 1990 German reunification, whereby the Four Powers renounced all rights they formerly held in the newly single country, including Berlin. The treaty came into force on 15 March 1991. Under the terms of the Treaty, the Allies were allowed to keep troops in Berlin until the end of 1994 (articles 4 and 5). In accordance with the Treaty, occupying troops were withdrawn by that deadline.

See also

*End of World War II in Asia

World War II officially ended in Asia on September 2, 1945, with the surrender of Japan on the . Before that, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, and the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, causing Emperor Hirohito to announce ...

* Aftermath of World War II

The aftermath of World War II was the beginning of a new era started in late 1945 (when World War II ended) for all countries involved, defined by the decline of all colonial empires and simultaneous rise of two superpowers; the Soviet Union (US ...

* Allied Commission

Following the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allies were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far East ...

s

* Council of Foreign Ministers

Council of Foreign Ministers was an organisation agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference in 1945 and announced in the Potsdam Agreement and dissolved upon the entry into force of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany in 1991.

Th ...

* German Instrument of Surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the "Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capit ...

* Liberation of France

The liberation of France in the Second World War was accomplished through diplomacy, politics and the combined military efforts of the Allied Powers, Free French forces in London and Africa, as well as the French Resistance.

Nazi Germany inva ...

* Line of contact

* Surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Jewel Voice Broadcast, announced by Emperor of Japan, Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in A ...

* Western betrayal

Western betrayal is the view that the United Kingdom, France, and sometimes the United States failed to meet their legal, diplomatic, military, and moral obligations with respect to the Czechoslovak and Polish states during the prelude to and a ...

* German prisoners of war in northwest Europe

More than 2.8 million German soldiers surrendered on the Western Front between D-Day (June 6, 1944) and the end of April 1945; 1.3 million between D-Day and March 31, 1945;2,055,575 German soldiers surrendered between D-Day and April 16, 1945, '' ...

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * *Further reading

Deutsche Welle special coverage of the end of World War II

��features a global perspective.

On this Day 7 May 1945: Germany signs unconditional surrender

Account of German surrender

BBC * Charles Kiley ( Stars and Stripes Staff Writer

Details of the Surrender Negotiations ''This Is How Germany Gave Up''

* ttp://english.pobediteli.ru/ Multimedia map of the war(1024x768 & Macromedia Flash Plugin 7.x)

External links

* * {{Authority control 1945 in military history 1945 in Europe European theatre of World War II Military history of Germany during World War II Chronology of World War II